Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mirach

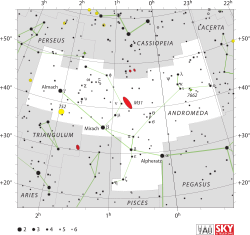

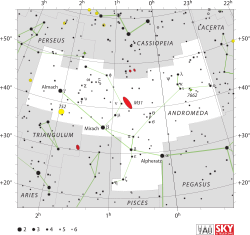

View on WikipediaMirach is a prominent star in the northern constellation of Andromeda. It is pronounced /ˈmaɪræk/[16][17] and has the Bayer designation Beta Andromedae, which is Latinized from β Andromedae. This star is positioned northeast of the Great Square of Pegasus and is potentially visible to all observers north of latitude 54° S. It is commonly used by stargazers to find the Andromeda Galaxy. The galaxy NGC 404, also known as Mirach's Ghost, is seven arcminutes away from Mirach.[18]

This star has an apparent visual magnitude of around 2.07,[1] varying between 2.01 and 2.10,[2] which at times makes it the brightest star in the constellation. Based upon parallax measurements, it is roughly 197 light-years (60 parsecs) from the Solar System.[10] Its apparent magnitude is reduced by 0.06 by extinction due to gas and dust along the line of sight.[9] The star has a negligible radial velocity of 0.1 km/s,[9] but with a relatively large proper motion, traversing the celestial sphere at an angular rate of 0.208″·yr−1.[19]

Properties

[edit]

Mirach is a single,[21] aging red giant with a stellar classification of M0 III.[4] It is currently on the asymptotic giant branch of its evolution.[3] The star has an estimated 2.49 times the mass of the Sun.[12] Having exhausted the supply of hydrogen at its core, the outer envelope of the star has expanded to around 86 times the size of the Sun. It is radiating 1,675 times the luminosity of the Sun[13] at an effective temperature of 3,762 K.[14] Mirach is suspected of being a semiregular variable star, with an apparent visual magnitude varies from +2.01 to +2.10.[2] Since 1943 the spectrum of this star has been one of the stable anchor points by which other stars are classified.[22]

Nomenclature

[edit]Beta Andromedae is the star's Bayer designation. It had the traditional name of Mirach, and its variations, such as Mirac, Mirar, Mirath, Mirak, etc. (the name is spelled Merach in Burritt's The Geography of the Heavens),[23] which come from the star's description in the Alfonsine Tables of 1521 as super mizar. Here, mirat is a corruption of the Arabic مئزر mīzar "girdle", which appeared in a Latin translation of the Almagest.[15] This word refers to Mirach's position at the left hip of the princess Andromeda.[24] In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[25] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016[26] included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN; which included Mirach for this star.

Mirach is listed in the Babylonian MUL.APIN as KA.MUSH.I.KU.E, meaning "the Deleter" (the alternative star is α Cas).[27] Medieval astronomers writing in Arabic called Mirach Janb al-Musalsalah (English: The Side of the Chained (Lady)); it was part of the 28th manzil (Arabian lunar mansion) Baṭn al-Ḥūt, the Belly of the Fish, or Qalb al-Ḥūt, the Heart of the Fish.[15][28] The star has also been called Cingulum and Ventrale.[15] This al-Ḥūt was an indigenous Arabic constellation, not the Western "Northern Fish" part of the constellation Pisces.[28] These names are not from the Arabic marāqq, loins, because it was never called al-Marāqq in Arabian astronomy.[28] Al Rishā', the Cord (of the well-bucket), on al-Sūfī's star map. It is the origin of the proper name Alrescha for Alpha Piscium.[15][29]

In Chinese, 奎宿 (Kuí Sù), meaning Legs, refers to an asterism consisting of Mirach (β Andromedae), η Andromedae, 65 Piscium, ζ Andromedae, ε Andromedae, δ Andromedae, π Andromedae, ν Andromedae, μ Andromedae, σ Piscium, τ Piscium, 91 Piscium, υ Piscium, φ Piscium, χ Piscium and ψ1 Piscium. Consequently, the Chinese name for β Andromedae itself is 奎宿九 (Kuí Sù jiǔ, English: the Ninth Star of Legs).[30] Mirach was considered the standard "black" star; black could mean "dark red" in this context, especially in comparison to Antares, the standard red star.[31]

The people of Micronesia named this star Kyyw, meaning "The Porpoise", and this was used as one of the names of the months in Micronesia.[32]

Substellar companion

[edit]A 2023 study detected radial velocity variations in Mirach (HD 6860), showing evidence of a substellar companion, likely a brown dwarf.[5]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | ≥28.26+2.05 −2.17 MJ |

2.03±0.01 | 663.87+4.61 −4.31 |

0.28+0.10 −0.09 |

— | — |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "HD 6860 Overview". NASA Exoplanet Archive. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ a b c d Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; Al, Et (November 2004). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Combined General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2004)". VizieR Online Data Catalog. 2250: II/250. Bibcode:2004yCat.2250....0S. Mirach's database entry at VizieR.

- ^ a b Eggen, Olin J. (July 1992). "Asymptotic giant branch stars near the sun". Astronomical Journal. 104 (1): 275–313. Bibcode:1992AJ....104..275E. doi:10.1086/116239.

- ^ a b Morgan, W. W.; Keenan, P. C. (1973). "Spectral Classification". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 11 (1): 29. Bibcode:1973ARA&A..11...29M. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.11.090173.000333.

- ^ a b c d e Lee, Byeong-Cheol; Do, Hee-Jin; et al. (October 2023). "Long-period radial velocity variations of nine M red giants: The detection of sub-stellar companions around HD 6860 and HD 112300". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 678: A106. arXiv:2307.15897. Bibcode:2023A&A...678A.106L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243725.

- ^ a b Johnson, H. L.; et al. (1966). "UBVRIJKL photometry of the bright stars". Communications of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. 4 (99): 99. Bibcode:1966CoLPL...4...99J.

- ^ a b "bet And". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ Hoffleit, D.; Warren, W. H., Jr. (1995-11-01). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Bright Star Catalogue, 5th Revised Ed. (Hoffleit+, 1991)". VizieR Online Data Catalog. 5050: V/50. Bibcode:1995yCat.5050....0H. Mirach's database entry at VizieR.

- ^ a b c Famaey, B.; et al. (January 2005). "Local kinematics of K and M giants from CORAVEL/Hipparcos/Tycho-2 data. Revisiting the concept of superclusters". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 430 (1): 165–186. arXiv:astro-ph/0409579. Bibcode:2005A&A...430..165F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041272. S2CID 17804304.

- ^ a b c d van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Elgarøy, Øystein; Engvold, Oddbjørn; Lund, Niels (March 1999). "The Wilson-Bappu effect of the MgII K line - dependence on stellar temperature, activity and metallicity". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 343: 222–228. Bibcode:1999A&A...343..222E.

- ^ a b Dehaes, S.; et al. (September 2011). "Structure of the outer layers of cool standard stars". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 533: A107. arXiv:0905.1240. Bibcode:2011A&A...533A.107D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912442. S2CID 42053871.

- ^ a b c McDonald, I.; Zijlstra, A. A.; Watson, R. A. (2017-10-01). "Fundamental parameters and infrared excesses of Tycho-Gaia stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 471: 770–791. arXiv:1706.02208. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.471..770M. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx1433. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ a b c d Dencs, Z.; Derekas, A.; Mitnyan, T.; Andersen, M. F.; Cseh, B.; Grundahl, F.; Hegedűs, V.; Kovács, J.; Kriskovics, L.; Palle, P. L.; Pál, A.; Szigeti, L.; Mészáros, Sz. (May 2024). "Atmospheric Parameters and Abundances of Cool Red Giant Stars". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 136 (5): 054202. arXiv:2404.13176. doi:10.1088/1538-3873/ad4177. ISSN 1538-3873.

- ^ a b c d e Allen, R. A. (1899). Star-names and Their Meanings. p. 36.

- ^ Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006). A Dictionary of Modern star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations (2nd rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Sky Pub. ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ^ "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ Darling, David. "Mirach's Ghost (NGC 404)". The Internet Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ^ Lépine, Sébastien; Shara, Michael M. (March 2005). "A Catalog of Northern Stars with Annual Proper Motions Larger than 0.15" (LSPM-NORTH Catalog)". The Astronomical Journal. 129 (3): 1483–1522. arXiv:astro-ph/0412070. Bibcode:2005AJ....129.1483L. doi:10.1086/427854. S2CID 2603568.

- ^ "/ftp/cats/more/HIP/cdroms/cats". Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Strasbourg astronomical Data Center. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Eggleton, P. P.; Tokovinin, A. A. (September 2008). "A catalogue of multiplicity among bright stellar systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 389 (2): 869–879. arXiv:0806.2878. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.389..869E. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13596.x. S2CID 14878976.

- ^ Garrison, R. F. (December 1993). "Anchor Points for the MK System of Spectral Classification". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 25: 1319. Bibcode:1993AAS...183.1710G. Archived from the original on 2019-06-25. Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- ^ Burritt, Elijah Hinsdale; Mattison, Hiram; Whitall, Henry (1856). The Geography of the Heavens. New York: Sheldon & Company. p. 18. Retrieved 2025-03-21.

- ^ Mirach, MSN Encarta. Accessed on line August 19, 2008. Archived 2009-10-31.

- ^ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ Rogers, J. H. (February 1998). "Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (1): 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- ^ a b c Davis Jr., George A. (1971). Selected List of Star Names. p. 5.

- ^ Kunitsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006). A Dictionary of Modern Star names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Sky Publishing Corp. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ^ (in Chinese) AEEA (Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy) 天文教育資訊網 2006 年 5 月 19 日 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Neuhäuser, R; Torres, G; Mugrauer, M; Neuhäuser, D L; Chapman, J; Luge, D; Cosci, M (2022-07-29). "Colour evolution of Betelgeuse and Antares over two millennia, derived from historical records, as a new constraint on mass and age". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 516 (1): 693–719. arXiv:2207.04702. doi:10.1093/mnras/stac1969. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Kelley, David H.; Milone, Eugene F. (2011). Exploring Ancient Skies: A Survey of Ancient and Cultural Astronomy. Aveni, Berlin: Springer. p. 345.

Further reading

[edit]- Davis Jr., G. A., (1971) Pronunciations, Derivations, and Meanings of a Selected List of Star Names, (rep.) Cambridge, Sky Publishing Corp.

- Kunitzsch, P., (1959) Arabische Sternnamen in Europa

- Kunitzsch. P., (ed.) (1990) Der Sternkatalog des Almagest, Band II

External links

[edit]- Kaler, James B., Mirach, retrieved 2021-05-28.

- Image MIRACH

- Mirach on WikiSky: DSS2, SDSS, GALEX, IRAS, Hydrogen α, X-Ray, Astrophoto, Sky Map, Articles and images

Mirach

View on GrokipediaNomenclature and Cultural Significance

Traditional Names and Etymology

The traditional name Mirach for Beta Andromedae derives from medieval Arabic astronomy, stemming from the word mīzar (مئزر), meaning "girdle" or "loin cloth," which alludes to the star's position at the waist or hip of the constellation figure representing Andromeda.[6] This nomenclature reflects the descriptive practices of early Islamic astronomers who mapped stars relative to mythological or human-like forms in the sky.[3] Historical variants of the name include Merach, Mirac, Mirar, Mirath, and Mirak, arising from transliteration differences in Latin and European texts adapting Arabic sources.[3] In medieval Arabic treatises, the star was also designated Janb al-Musalsalah (جَنْب الْمُسَلْسَلَة), translating to "the side of the chained lady," further highlighting its anatomical placement on Andromeda's chained posture in the asterism.[7] The Bayer designation Beta Andromedae, assigned in the early 17th century, provided the foundation for adopting Mirach as the standardized proper name.[6] On June 30, 2016, the International Astronomical Union (IAU), through its Working Group on Star Names (WGSN), officially approved Mirach as the proper name for this star, drawing from its long-established traditional usage to promote global consistency in astronomical nomenclature.[8] Beyond Arabic traditions, Mirach holds cultural significance in Micronesian societies, where it is known as Kyyw, meaning "the porpoise," a name that also denoted one of the months in their lunar calendar and contributed to the star lore employed by navigators for wayfinding across the Pacific.[3]Astronomical Designations

Mirach holds the Bayer designation Beta Andromedae (β And), identifying it as the second-brightest star in the constellation Andromeda after Alpha Andromedae.[9] It also bears the Flamsteed designation 43 Andromedae, assigned in the early 18th-century star atlas Historia Coelestis Britannica.[9] In modern catalogs, Mirach is entry HD 6860 in the Henry Draper Catalogue, a comprehensive 20th-century compilation of stellar spectra and positions.[9] Its equatorial coordinates in the J2000.0 epoch are right ascension 01ʰ 09ᵐ 43.92ˢ and declination +35° 37′ 14.0″.[9] Additionally, the Hipparcos Catalogue designates it as HIP 5447, based on astrometric data from the 1990s ESA mission that refined positions for over 100,000 stars.[9] The International Astronomical Union formally approved Mirach as the proper name for Beta Andromedae in 2016.[8]Role in Mythology and Navigation

In Greek mythology, Mirach (Beta Andromedae) forms a key part of the constellation Andromeda, representing the chained princess sacrificed to a sea monster as punishment for her mother Cassiopeia's hubris; the star specifically marks the waist or girdle of the figure, emphasizing her bound and vulnerable posture in ancient depictions.[10] This positioning aligns with Ptolemy's second-century catalog, where Mirach is described as the southernmost of three stars draping over Andromeda's girdle, reinforcing the mythological narrative of captivity and rescue by Perseus.[10] In Arabic astronomy, Mirach was integral to the "girdle" asterism within Andromeda, known as al-mi'zar (girdle or loincloth), and featured prominently in navigational star catalogs such as the Zij al-Sindhind and Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi's Book of Fixed Stars (ca. 964 CE), where it served as a reference for determining celestial positions during maritime voyages.[11] Additionally, it formed the 28th lunar mansion (manzil), termed Baṭn al-Ḥūt (Belly of the Fish) or Qalb al-Hūt (Heart of the Fish), used by navigators like Ahmad ibn Majid in the 15th century to track lunar progress and orient ships across the Indian Ocean.[12] Micronesian voyagers, particularly from the Carolinian islands, incorporated Mirach into their star compass system for trans-Pacific wayfinding, identifying it as part of the Igulig (whale) asterism where it represents the whale's body, aiding in directional orientation alongside swells and winds during long voyages.[13] This usage was preserved and taught by master navigator Mau Piailug of Satawal, who employed such stellar patterns to guide non-instrument voyages, including the 1976 Hōkūleʻa expedition from Hawaii to Tahiti.[14] During the medieval period in Europe, Mirach appeared in star atlases derived from Arabic sources, such as the 13th-century Latin translations of al-Sufi's work, where it helped locate the Andromeda Nebula (now known as the Andromeda Galaxy) as a "nebulous spot" near the girdle stars of the constellation's Fish asterism.[15] These references, illustrated in manuscripts with dotted markers, facilitated early European astronomers' identification of the nebula relative to Mirach's position, bridging Islamic and Western celestial traditions.[15]Physical Characteristics

Stellar Parameters

Mirach possesses an apparent visual magnitude of 2.067, rendering it the 54th brightest star in the night sky. The star lies at a distance of 197 ± 7 light-years from the Solar System, as determined by parallax measurements from the Gaia mission. As a red giant, Mirach has expanded dramatically, attaining a radius of 86.4 solar radii () and a mass of 2.49 solar masses ().[16] Its luminosity reaches 1,675 solar luminosities (), derived from its measured distance and bolometric magnitude.[16] The effective temperature of Mirach's photosphere is 3,762 ± 40 K.[16]Spectral Classification and Atmosphere

Mirach is classified as an M0 III giant star in the Morgan-Keenan (MK) system, characterized by strong molecular absorption bands typical of cool, evolved red giants. This classification has remained stable since its establishment as a spectral standard in 1943, serving as a reference point for classifying other late-type stars. The star's orange-red appearance arises from its relatively cool effective temperature of 3,762 K, which shifts its peak emission into the infrared while producing a reddish hue in visible light. Prominent titanium oxide (TiO) absorption bands dominate its optical spectrum, particularly around 5900 Å and 6200 Å, contributing to the characteristic features of M-type giants. Mirach exhibits metallicity levels near solar, with an iron abundance of [Fe/H] ≈ -0.30, indicating a composition broadly similar to the Sun's despite slight depletion in heavier elements. As a red giant, its atmosphere is expanded, resulting in low surface gravity (log g ≈ 1.1), which influences the broadening of spectral lines and the overall atmospheric structure.Evolutionary Stage

Mirach is currently located on the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) of its evolutionary track, a phase that follows the ascent of the red giant branch (RGB), during which the star experiences thermal pulses driven by helium shell fusion surrounding an inert carbon-oxygen core. This stage marks a period of instability and enhanced mass loss as the star's envelope expands dramatically. The star's progenitor was a main-sequence A-type star with an initial mass of approximately 2.5 solar masses, from which it evolved roughly 100 million years ago after exhausting its core hydrogen fuel. Stellar evolution models for such intermediate-mass stars place Mirach's total age at 0.5–1 billion years. Looking ahead, Mirach will continue to expand into a supergiant, intensifying its stellar winds and shedding outer layers, ultimately ejecting material to form a planetary nebula while leaving a white dwarf remnant as its core cools.[6] Its substantial radius and luminosity underscore this late giant phase in the star's lifecycle.[5]Variability and Orbital Properties

Semiregular Variability

Mirach is classified as a suspected semiregular variable star, typical for late-type giants exhibiting irregular or poorly defined pulsational cycles.[17] This type is characterized by small-amplitude brightness variations without a dominant periodicity, often spanning periods longer than 30 days but lacking consistent repetition.[18] The star's apparent visual magnitude shows fluctuations of 0.09 magnitudes, ranging from +2.01 to +2.10, as reported in observational catalogs. These variations arise from intrinsic pulsations associated with the star's red giant status on the asymptotic giant branch, where thermal instabilities and convective motions in the extended envelope drive irregular expansions and contractions.[18] Long-term monitoring by the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) has documented these irregular changes through visual and photometric observations spanning decades, confirming the lack of a stable period despite short-term fluctuations around 41 days noted in some datasets.[17] The modest amplitude of Mirach's variability ensures that it remains steadily visible to the naked eye, with changes too subtle to be discerned without instrumental aid, preserving its utility as a reliable guide star in the constellation Andromeda.[17]Proper Motion and Space Velocity

Mirach has a proper motion of 175.90 mas/year in right ascension and -112.20 mas/year in declination, according to data from the Gaia DR3 catalog. This transverse motion across the sky corresponds to a tangential velocity of approximately 60 km/s at its distance of about 61 pc, providing insight into the star's path through the local stellar neighborhood. The radial velocity of Mirach is measured at +0.06 ± 0.13 km/s, indicating negligible motion along the line of sight relative to the Solar System. Combining this with the proper motion yields space velocity components relative to the local standard of rest that position Mirach on a typical orbit within the Milky Way's thin disk, characterized by low eccentricity and no substantial peculiar motion that might indicate dynamical influences from an undetected massive companion beyond the known substellar object.System Components

Stellar Companion

Mirach has a faint visual companion, a low-mass hydrogen-fusing dwarf star with an apparent magnitude of 14, located at a projected separation of approximately 1,700 AU. This companion is over 60,000 times less luminous than Mirach and is visible in moderate-sized telescopes. The nature of their orbit is not fully determined, but they form a wide binary system.[6]Substellar Companion

In 2023, a substellar companion to Mirach (Beta Andromedae, HD 6860) was discovered through long-term radial velocity monitoring conducted at the Bohyunsan Observatory using the high-resolution Bohyunsan Observatory Echelle Spectrograph (BOES).[19] This detection revealed periodic variations in the star's radial velocity, confirming the presence of an orbiting substellar object with a minimum mass of Jupiter masses (), placing it firmly in the brown dwarf regime given the hydrogen-burning mass limit of approximately 13 .[19] The companion's orbit was characterized using a Keplerian model fitted to 44 high-precision spectra spanning from December 2005 to December 2021, yielding an orbital period of days, a semi-major axis of AU, and an eccentricity of .[19] These parameters were derived via Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulations, assuming a host star mass of 2.49 solar masses (), which scales the companion's gravitational influence on the primary's motion.[19] No direct imaging of the companion has been achieved to date, limiting confirmation of its true mass and inclination, though the minimum mass suggests a likely brown dwarf nature rather than a planet.[19] This discovery highlights the potential for substellar companions around evolved M giants like Mirach, contributing to understanding companion survival during stellar expansion.[19]Association with Nearby Celestial Objects

Mirach, the bright red giant star Beta Andromedae, appears in close visual proximity to the lenticular galaxy NGC 404, separated by an angular distance of about 7 arcminutes. This faint object, with an apparent magnitude of 10.3, is often obscured by Mirach's glare in visible light, earning it the nickname "Mirach's Ghost." The galaxy was discovered by William Herschel in 1784, who described it as a nebulous patch near the star. NGC 404 lies approximately 10 million light-years distant, far beyond Mirach's own distance of 197 light-years, confirming no physical connection and attributing their alignment to a mere line-of-sight coincidence.[21]Observation and Significance

Visibility and Location in the Sky

Mirach, also known as Beta Andromedae, occupies a prominent position in the constellation Andromeda, lying approximately halfway along the figure's "body" between the stars Alpheratz (Alpha Andromedae) and Almach (Gamma Andromedae).[22] It appears just below the northeastern side of the Great Square asterism in the neighboring constellation Pegasus, making it a distinctive orange-red point of light in that region of the sky.[5] This second-magnitude star is easily visible to the naked eye from all locations north of about 54° south latitude, owing to its declination of approximately +35.6°.[2] For observers in the Northern Hemisphere, Mirach culminates—reaching its highest point in the sky—around November, when it transits the meridian near midnight.[23] It is best observed during autumn evenings, from September through November, when the constellation rises early in the evening and arcs high overhead.[23] In mid-northern latitudes (around 40° to 50° N), Mirach can reach altitudes of approximately 76° to 86° above the horizon at culmination, providing excellent viewing conditions with minimal atmospheric distortion.[2] Its apparent visual magnitude of 2.06 ensures minimal interference from light pollution, allowing detection even in suburban skies, though darker sites enhance the experience.[2] For precise locating with star charts or apps, Mirach's equatorial coordinates are right ascension 01h 09m 44s and declination +35° 37'.[2]Use as a Guide Star

Mirach serves as a primary guide star for locating the Andromeda Galaxy (M31), one of the most prominent deep-sky objects visible to amateur astronomers. M31 lies approximately 8° northwest of Mirach and can be located by star-hopping from Mirach northwest about 3.5° to the magnitude 4.5 star ν Andromedae, then continuing a similar distance further northwest; this positions M31 as a faint fuzzy patch accessible even under moderate light pollution with binoculars or the naked eye on clear nights.[5][24] The star also aids in spotting other nearby galaxies using binoculars or small telescopes. For the Triangulum Galaxy (M33), a fainter spiral, one extends a line from Mu Andromedae through Mirach and continues roughly twice that distance, revealing M33 as a challenging but rewarding target for averted vision. Similarly, NGC 404—known as Mirach's Ghost due to its proximity—lies just 7 arcminutes north of the star, allowing contextual pointing in telescopic setups where the bright Mirach helps frame the faint lenticular galaxy for observation.[5] In astrophotography, Mirach's magnitude 2.06 brightness and strategic position facilitate field alignment and focusing for imaging nearby objects, such as NGC 404, which has been captured using modest equipment like 120 mm refractor telescopes centered on the star. Recent observations in 2025 highlighted Mirach's utility when Comet C/2025 F2 (SWAN) passed just south of it in April, enabling observers to track the comet's path eastward through Andromeda by using the star as a reference point in the morning sky.[5][25][26]References

- https://apod.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/apod/ap031029.html