Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stellar core

View on WikipediaA stellar core is the extremely hot, dense region at the center of a star. For an ordinary main sequence star, the core region is the volume where the temperature and pressure conditions allow for energy production through thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium. This energy in turn counterbalances the mass of the star pressing inward; a process that self-maintains the conditions in thermal and hydrostatic equilibrium. The minimum temperature required for stellar hydrogen fusion exceeds 107 K (10 MK), while the density at the core of the Sun is over 100 g/cm3. The core is surrounded by the stellar envelope, which transports energy from the core to the stellar atmosphere where it is radiated away into space.[1]

Main sequence

[edit]

Main sequence stars are distinguished by the primary energy-generating mechanism in their central region, which joins four hydrogen nuclei to form a single helium atom through thermonuclear fusion. The Sun is an example of this class of stars. Once stars with the mass of the Sun form, the core region reaches thermal equilibrium after about 100 million (108)[2][verification needed] years and becomes radiative.[3] This means the generated energy is transported out of the core via radiation and conduction rather than through mass transport in the form of convection. Above this spherical radiation zone lies a small convection zone just below the outer atmosphere.

At lower stellar mass, the outer convection shell takes up an increasing proportion of the envelope, and for stars with a mass of around 0.35 M☉ (35% of the mass of the Sun) or less (including failed stars) the entire star is convective, including the core region.[4] These very low-mass stars (VLMS) occupy the late range of the M-type main-sequence stars, or red dwarf. The VLMS form the primary stellar component of the Milky Way at over 70% of the total population. The low-mass end of the VLMS range reaches about 0.075 M☉, below which ordinary (non-deuterium) hydrogen fusion does not take place and the object is designated a brown dwarf. The temperature of the core region for a VLMS decreases with decreasing mass, while the density increases. For a star with 0.1 M☉, the core temperature is about 5 MK while the density is around 500 g cm−3. Even at the low end of the temperature range, the hydrogen and helium in the core region is fully ionized.[4]

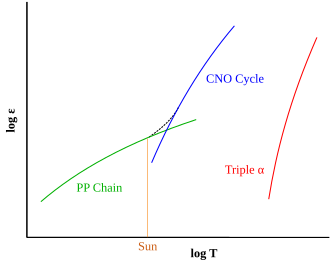

Below about 1.2 M☉, energy production in the stellar core is predominantly through the proton–proton chain reaction, a process requiring only hydrogen. For stars above this mass, the energy generation comes increasingly from the CNO cycle, a hydrogen fusion process that uses intermediary atoms of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen. In the Sun, only 1.5% of the net energy comes from the CNO cycle. For stars at 1.5 M☉ where the core temperature reaches 18 MK, half the energy production comes from the CNO cycle and half from the pp chain.[5] The CNO process is more temperature-sensitive than the pp chain, with most of the energy production occurring near the very center of the star. This results in a stronger thermal gradient, which creates convective instability. Hence, the core region is convective for stars above about 1.2 M☉.[6]

For all masses of stars, as the core hydrogen is consumed, the temperature increases so as to maintain pressure equilibrium. This results in an increasing rate of energy production, which in turn causes the luminosity of the star to increase. The lifetime of the core hydrogen–fusing phase decreases with increasing stellar mass. For a star with the mass of the Sun, this period is around ten billion years. At 5 M☉ the lifetime is 65 million years while at 25 M☉ the core hydrogen–fusing period is only six million years.[7] The longest-lived stars are fully convective red dwarfs, which can stay on the main sequence for hundreds of billions of years or more.[8]

Subgiant stars

[edit]Once a star has converted all the hydrogen in its core into helium, the core is no longer able to support itself and begins to collapse. It heats up and becomes hot enough for hydrogen in a shell outside the core to start fusion. The core continues to collapse and the outer layers of the star expand. At this stage, the star is a subgiant. Very-low-mass stars never become subgiants because they are fully convective.[9]

Stars with masses between about 0.4 M☉ and 1 M☉ have small non-convective cores on the main sequence and develop thick hydrogen shells on the subgiant branch. They spend several billion years on the subgiant branch, with the mass of the helium core slowly increasing from the fusion of the hydrogen shell. Eventually, the core becomes degenerate, where the dominant source of core pressure is electron degeneracy pressure, and the star expands onto the red giant branch.[9]

Stars with higher masses have at least partially convective cores while on the main sequence, and they develop a relatively large helium core before exhausting hydrogen throughout the convective region, and possibly in a larger region due to convective overshoot. When core fusion ceases, the core starts to collapse and it is so large that the gravitational energy actually increases the temperature and luminosity of the star for several million years before it becomes hot enough to ignite a hydrogen shell. Once hydrogen starts fusing in the shell, the star cools and it is considered to be a subgiant. When the core of a star is no longer undergoing fusion, but its temperature is maintained by fusion of a surrounding shell, there is a maximum mass called the Schönberg–Chandrasekhar limit. When the mass exceeds that limit, the core collapses, and the outer layers of the star expand rapidly to become a red giant. In stars up to approximately 2 M☉, this occurs only a few million years after the star becomes a subgiant. Stars more massive than 2 M☉ have cores above the Schönberg–Chandrasekhar limit before they leave the main sequence.[9]

Giant stars

[edit]

Once the supply of hydrogen at the core of a low-mass star with at least 0.25 M☉[8] is depleted, it will leave the main sequence and evolve along the red giant branch of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. Those evolving stars with up to about 1.2 M☉ will contract their core until hydrogen begins fusing through the pp chain along with a shell around the inert helium core, passing along the subgiant branch. This process will steadily increase the mass of the helium core, causing the hydrogen-fusing shell to increase in temperature until it can generate energy through the CNO cycle. Due to the temperature sensitivity of the CNO process, this hydrogen fusing shell will be thinner than before. Non-core convecting stars above 1.2 M☉ that have consumed their core hydrogen through the CNO process, contract their cores, and directly evolve into the giant stage. The increasing mass and density of the helium core will cause the star to increase in size and luminosity as it evolves up the red giant branch.[10]

For stars in the mass range 0.4–1.5 M☉, the helium core becomes degenerate before it is hot enough for helium to start fusion. When the density of the degenerate helium at the core is sufficiently high − at around 107 g cm−3 with a temperature of about 109 K − it undergoes a nuclear explosion known as a "helium flash". This event is not observed outside the star, as the unleashed energy is entirely used up to lift the core from electron degeneracy to normal gas state. The helium fusing core expands, with the density decreasing to about 103 − 104 g cm−3, while the stellar envelope undergoes a contraction. The star is now on the horizontal branch, with the photosphere showing a rapid decrease in luminosity combined with an increase in the effective temperature.[11]

In the more massive main-sequence stars with core convection, the helium produced by fusion becomes mixed throughout the convective zone. Once the core hydrogen is consumed, it is thus effectively exhausted across the entire convection region. At this point, the helium core starts to contract and hydrogen fusion begins along with a shell around the perimeter, which then steadily adds more helium to the inert core.[7] At stellar masses above 2.25 M☉, the core does not become degenerate before initiating helium fusion.[12] Hence, as the star ages, the core continues to contract and heat up until a triple alpha process can be maintained at the center, fusing helium into carbon. However, most of the energy generated at this stage continues to come from the hydrogen fusing shell.[7]

For stars above 10 M☉, helium fusion at the core begins immediately as the main sequence comes to an end. Two hydrogen fusing shells are formed around the helium core: a thin CNO cycle inner shell and an outer pp chain shell.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pradhan & Nahar 2011, p. 624

- ^ Lodders & Fegley 2015, p. 126

- ^ Maeder 2008, p. 519

- ^ a b Chabrier & Baraffe 1997, pp. 1039−1053

- ^ Lang 2013, p. 339

- ^ Maeder 2008, p. 624

- ^ a b c Iben 2013, p. 45

- ^ a b Adams, Laughlin & Graves 2004

- ^ a b c Salaris & Cassisi 2005, p. 140

- ^ Rose 1998, p. 267

- ^ Hansen, Kawaler & Trimble 2004, p. 63

- ^ Bisnovatyi-Kogan 2001, p. 66

- ^ Maeder 2008, p. 760

Bibliography

[edit]- Adams, Fred C.; Laughlin, Gregory; Graves, Genevieve J. M. (2004). Red Dwarfs and the End of the Main Sequence. Gravitational Collapse: From Massive Stars to Planets. Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica, Serie de Conferencias. Vol. 22. Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica. pp. 46–49. Bibcode:2004RMxAC..22...46A.

- Bisnovatyi-Kogan, G.S. (2001), Stellar Physics: Stellar Evolution and Stability, Astronomy and Astrophysics Library, translated by Blinov, A.Y.; Romanova, M., Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 9783540669876

- Chabrier, Gilles; Baraffe, Isabelle (November 1997), "Structure and evolution of low-mass stars", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 327: 1039−1053, arXiv:astro-ph/9704118, Bibcode:1997A&A...327.1039C.

- Hansen, Carl J.; Kawaler, Steven D.; Trimble, Virginia (2004), Stellar Interiors: Physical Principles, Structure, and Evolution, Astronomy and Astrophysics Library (2nd ed.), Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 9780387200897

- Iben, Icko (2013), Stellar Evolution Physics: Physical processes in stellar interiors, Cambridge University Press, p. 45, ISBN 9781107016569.

- Lang, Kenneth R. (2013), Essential Astrophysics, Undergraduate Lecture Notes in Physics, Springer Science & Business Media, p. 339, ISBN 978-3642359637.

- Lodders, Katharina; Fegley, Bruce Jr. (2015), Chemistry of the Solar System, Royal Society of Chemistry, p. 126, ISBN 9781782626015.

- Maeder, Andre (2008), Physics, Formation and Evolution of Rotating Stars, Astronomy and Astrophysics Library, Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 9783540769491.

- Pradhan, Anil K.; Nahar, Sultana N. (2011), Atomic Astrophysics and Spectroscopy, Cambridge University Press, pp. 226−227, ISBN 978-1139494977.

- Rose, William K. (1998), Advanced Stellar Astrophysics, Cambridge University Press, p. 267, ISBN 9780521588331

- Salaris, Maurizio; Cassisi, Santi (2005), Evolution of Stars and Stellar Populations, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9780470092224