Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mu Arae

View on Wikipedia

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

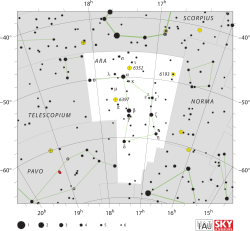

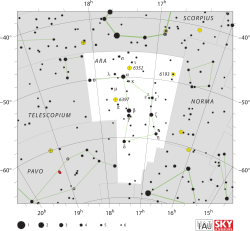

| Constellation | Ara |

| Right ascension | 17h 44m 08.70314s[1] |

| Declination | −51° 50′ 02.5916″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 5.15[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | G3IV–V[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 5.15±0.01[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (G) | 4.943±0.003[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (K) | 3.68±0.25[2] |

| U−B color index | +0.24[4] |

| B−V color index | +0.70[4] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −9.54±0.13[1] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −15.034 mas/yr[1] Dec.: −190.901 mas/yr[1] |

| Parallax (π) | 64.0853±0.0904 mas[1] |

| Distance | 50.89 ± 0.07 ly (15.60 ± 0.02 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | +4.17[5] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 1.10±0.01[6] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.280±0.025[7] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 1.879±0.019[7] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.30±0.03[7] cgs |

| Temperature | 5,974±61[7] K |

| Metallicity | 200±5%[6][note 1] |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | 0.29±0.01[7] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 3.1±0.5[2] km/s |

| Age | 6.34±0.40[6] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Cervantes, μ Arae, CD−51°11094, FK5 662, GC 24024, GJ 691, HD 160691, HIP 86796, HR 6585, SAO 244981, PPM 346258, LTT 7053[8] | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| Exoplanet Archive | data |

| ARICNS | data |

Mu Arae is a single star with a planetary system in the constellation of Ara. Its name is a Bayer designation that is Latinized from μ Arae, and abbreviated Mu Ara or μ Ara. This star is officially named Cervantes, pronounced /sɜːrˈvæntiːz/ or sur-VAN-teez,[9] and is often designated HD 160691. With an apparent visual magnitude of 5.15,[2] it is faintly visible to the naked eye. Based on parallax measurements it is located approximately 51 light-years (16 pc) away from the Sun.[1] It is drifting closer with a radial velocity of −10 km/s.[1]

Cervantes is similar to the Sun, but is older, 10% more massive, and slightly evolved. It has four known extrasolar planets designated Mu Arae b, c, d and e; later named Quijote, Dulcinea, Rocinante and Sancho, respectively. Three of them have masses comparable with that of Jupiter. Mu Arae c, the innermost, was the first hot Neptune or super-Earth discovered.

Nomenclature

[edit]μ Arae (Latinised to Mu Arae) is the star's Bayer designation. HD 160691 is the entry in the Henry Draper Catalogue.

The established convention for extrasolar planets is that the planets receive designations consisting of the star's name followed by lower-case Roman letters starting from "b", in order of discovery.[10] This system was used by a team led by Krzysztof Goździewski.[11] On the other hand, a team led by Francesco Pepe proposed a modification of the designation system, where the planets are designated in order of characterization.[12] Since the parameters of the outermost planet were poorly constrained before the introduction of the 4-planet model of the system, this results in a different order of designations for the planets in the Mu Arae system. Both systems agree on the designation of the 640-day planet as "b". The old system designates the 9-day planet as "d", the 310-day planet as "e" and the outer planet as "c". Since the International Astronomical Union has not defined an official system for designations of extrasolar planets,[13] the issue of which convention is 'correct' remains open, however most subsequent scientific publications about this system appear to have adopted the Pepe et al. system, as has the system's entry in the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia.[14][15]

In July 2014 the International Astronomical Union launched NameExoWorlds, a process for giving proper names to certain exoplanets and their host stars.[16] The process involved public nomination and voting for the new names.[17] In December 2015, the IAU announced the winning names were Cervantes for this star and Quijote, Dulcinea, Rocinante and Sancho, for its planets (b, c, d, and e, respectively; the IAU used the Pepe et al system).[18][19]

The winning names were those submitted by the Planetario de Pamplona, Spain. Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547–1616) was a famous Spanish writer and author of El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha. The planets are named after characters of that novel: Quijote was the lead character; Dulcinea his love interest; Rocinante his horse, and Sancho his squire.[20]

In 2016, the IAU organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[21] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. In its first bulletin of July 2016,[22] the WGSN explicitly recognized the names of exoplanets and their host stars approved by the Executive Committee Working Group Public Naming of Planets and Planetary Satellites, including the names of stars adopted during the 2015 NameExoWorlds campaign. This star is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[9]

Stellar characteristics

[edit]According to measurements made by the Gaia astrometric satellite, Mu Arae exhibits a parallax of 64.0853 milliarcseconds as the Earth moves around the Sun. When combined with the known distance from the Earth to the Sun, this means the star is located at a distance of 50.89 light-years (15.60 parsecs).[1][note 2] Seen from Earth it has an apparent magnitude of +5.15 and is thus visible to the naked eye.

Asteroseismic analysis of the star reveals it is approximately 10% more massive than the Sun and significantly older, at around 6.34 billion years.[6] The radius of the star is 28% greater than that of the Sun and it is 90% more luminous.[7] The star contains twice the abundance of iron relative to hydrogen of the Sun and is therefore described as metal-rich. Mu Arae is also more enriched than the Sun in the element helium.[6]

Mu Arae has a listed spectral type of G3IV–V.[3] The G3 part means the star is similar to the Sun (a G2V star). The star may be entering the subgiant stage of its evolution as it starts to run out of hydrogen in its core.[dubious – discuss] This is reflected in its borderline luminosity class, between IV (the subgiants) and V (main sequence dwarf stars like the Sun). This star has a low chromospheric activity level and a low, non-variable X-ray luminosity.[23]

Planetary system

[edit]

Discovery

[edit]In 2001, an extrasolar planet was announced by the Anglo-Australian Planet Search team, together with the planet orbiting Epsilon Reticuli. The planet, designated Mu Arae b, was thought to be in a highly eccentric orbit of around 743 days.[24] The discovery was made by analysing variations in the star's radial velocity (measured by observing the Doppler shift of the star's spectral lines) as a result of being pulled around by the planet's gravity. Further observations revealed the presence of a second object in the system (now designated as Mu Arae e), which was published in 2004. At the time, the parameters of this planet were poorly constrained and it was thought to be in an orbit of around 8.2 years with a high eccentricity.[25] Later in 2004, a small inner planet designated Mu Arae c was announced with a mass comparable with that of Uranus in a 9-day orbit. This was the first of the class of planets known as "hot Neptunes" to be discovered. The discovery was made by making high-precision radial velocity measurements with the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) spectrograph.[23]

In 2006, two teams, one led by Krzysztof Goździewski and the other by Francesco Pepe independently announced four-planet models for the radial velocity measurements of the star, with a new planet (Mu Arae d) in a near-circular orbit lasting approximately 311 days.[11][12] The new model gives revised parameters for the previously known planets, with lower eccentricity orbits than in the previous model and including a more robust characterization of the orbit of Mu Arae e. The discovery of the fourth planet made Mu Arae the second known four-planet extrasolar system, after 55 Cancri.

System architecture and habitability

[edit]The Mu Arae system consists of an inner Uranus-mass planet in a tight 9-day orbit and three massive planets, probably gas giants, on wide, near-circular orbits, which contrasts with the high-eccentricity orbits typically observed for long-period extrasolar planets. The Uranus-mass planet may be a chthonian planet, the core of a gas giant which has had its outer layers stripped away by stellar radiation.[26] Alternatively it may have formed in the inner regions of the Mu Arae system as a rocky "super-Earth".[23]

The inner gas giants "d" and "b" are located close to the 2:1 orbital resonance which causes them to undergo strong interactions. The best-fit solution to the system is actually unstable:[27][2] simulations suggest the system is destroyed after 78 million years, which is significantly shorter than the estimated age of the star system. More stable solutions, including ones in which the two planets are actually in the resonance (similar to the situation in the Gliese 876 system) can be found which give only a slightly worse fit to the data.[12] A 2022 study finds a stable orbital fit to the system, and estimates a lower limit on the system inclination of about 20°.[28]

Astrometric observations using the Hubble Space Telescope have not detected any of the known planets, but have set upper limits on the masses of the outer three planets: planet b is <4.3 MJ, planet d is <7.0 MJ, and planet e is <4.4 MJ.[2] Searches for circumstellar discs show no evidence for a debris disc similar to the Kuiper belt around Mu Arae. If Mu Arae does have a Kuiper belt, it is too faint to be detected with current instruments.[29]

The gas giant planet "b" is located in the liquid water habitable zone of Mu Arae. This would prevent an Earth-like planet from forming in the habitable zone, however large moons of the gas giant could potentially support liquid water. On the other hand, it is unclear whether moons sufficiently massive to retain an atmosphere and liquid water could actually form around a gas giant planet, due to a theorized scaling law between the mass of a planet and its satellite system.[30] In addition, measurements of the star's ultraviolet flux suggest that any potentially habitable planets or moons may not receive enough ultraviolet to trigger the formation of biomolecules.[31] Planet "d" would receive a similar amount of ultraviolet to the Earth and thus lies in the ultraviolet habitable zone. However, it would be too hot for any moons to support surface liquid water.

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c (Dulcinea) | ≥0.032±0.002 MJ | 0.092319±0.000005 | 9.638±0.001 | 0.090±0.042 | — | — |

| d (Rocinante) | ≥0.448±0.011 MJ | 0.9347±0.0015 | 308.36±0.29 | 0.055±0.014 | — | — |

| b (Quijote) | ≥1.65±0.009 MJ | 1.522±0.001 | 644.92±0.29 | 0.041±0.009 | — | — |

| e (Sancho) | ≥1.932±0.022 MJ | 5.204±0.021 | 4,019±24 | 0.049±0.011 | — | — |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c d e f g Benedict, G. F.; McArthur, B. E. (June 2022). "The μ Arae Planetary System: Radial Velocities and Astrometry". The Astronomical Journal. 163 (6): 295. arXiv:2204.13706. Bibcode:2022AJ....163..295B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac6ac8. S2CID 248476290.

- ^ a b Gray, R. O.; et al. (July 2006). "Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: Spectroscopy of Stars Earlier than M0 within 40 parsecs: The Northern Sample I". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (1): 161–170. arXiv:astro-ph/0603770. Bibcode:2006AJ....132..161G. doi:10.1086/504637. S2CID 119476992.

- ^ a b Feinstein, A. (1966). "Photoelectric observations of Southern late-type stars". The Information Bulletin for the Southern Hemisphere. 8: 30. Bibcode:1966IBSH....8...30F.

- ^ Anderson, E.; Francis, Ch. (2012). "XHIP: An extended hipparcos compilation". Astronomy Letters. 38 (5): 331. arXiv:1108.4971. Bibcode:2012AstL...38..331A. doi:10.1134/S1063773712050015. S2CID 119257644.

- ^ a b c d e Soriano, M.; Vauclair, S. (April 2010). "New seismic analysis of the exoplanet-host star Mu Arae". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 513: A49. arXiv:0903.5475. Bibcode:2010A&A...513A..49S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200911862. S2CID 5688996.

- ^ a b c d e f Soubiran, C.; et al. (1 February 2024). "Gaia FGK benchmark stars: Fundamental Teff and log g of the third version". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 682: A145. arXiv:2310.11302. Bibcode:2024A&A...682A.145S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202347136. ISSN 0004-6361. Mu Arae's database entry at VizieR.

- ^ "mu Ara". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 29 April 2025.

- ^ a b "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ Hessman, F. V.; et al. (2010). "On the naming convention used for multiple star systems and extrasolar planets". arXiv:1012.0707 [astro-ph.SR].

- ^ a b Gozdziewski, K.; Maciejewski, Andrzej J.; Migaszewski, Cezary (2007). "On the extrasolar multi-planet system around HD160691". The Astrophysical Journal. 657 (1): 546–558. arXiv:astro-ph/0608279. Bibcode:2007ApJ...657..546G. doi:10.1086/510554. S2CID 16620036.

- ^ a b c Pepe, F.; et al. (2006). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets. IX. μ Ara, a system with four planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 462 (2): 769–776. arXiv:astro-ph/0608396. Bibcode:2007A&A...462..769P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066194. S2CID 119071803.

- ^ "Planets Around Other Stars". IAU. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ Short, D.; et al. (2008). "New solutions for the planetary dynamics in HD160691 using a Newtonian model and latest data". MNRAS. 386 (1): L43 – L46. arXiv:0802.1781. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.386L..43S. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2008.00457.x. S2CID 15410895.

- ^ "Notes for star HD 160691". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ^ NameExoWorlds: An IAU Worldwide Contest to Name Exoplanets and their Host Stars. IAU.org. 9 July 2014

- ^ "NameExoWorlds The Process". Archived from the original on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ Final Results of NameExoWorlds Public Vote Released, International Astronomical Union, 15 December 2015.

- ^ "The Proposals page for Mu Arae". International Astronomical Union. 3 January 2016. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019.

- ^ NameExoWorlds The Approved Names

- ^ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Santos, N. C.; et al. (2004). "The HARPS survey for southern extra-solar planets II. A 14 Earth-masses exoplanet around μ Arae". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 426 (1): L19 – L23. arXiv:astro-ph/0408471. Bibcode:2004A&A...426L..19S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200400076. S2CID 14938593.

- ^ Butler; et al. (2001). "Two New Planets from the Anglo-Australian Planet Search". The Astrophysical Journal. 555 (1): 410–417. Bibcode:2001ApJ...555..410B. doi:10.1086/321467. hdl:2299/137. S2CID 122572834.

- ^ McCarthy, Chris; et al. (2004). "Multiple Companions to HD 154857 and HD 160691". The Astrophysical Journal. 617 (1): 575–579. arXiv:astro-ph/0409335. Bibcode:2004ApJ...617..575M. doi:10.1086/425214. S2CID 119446133.

- ^ Baraffe, I.; et al. (2006). "Birth and fate of hot-Neptune planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 450 (3): 1221–1229. arXiv:astro-ph/0512091. Bibcode:2006A&A...450.1221B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20054040. S2CID 15574680.

- ^ Agnew, Matthew T.; et al. (June 2019). "Predicting multiple planet stability and habitable zone companions in the TESS era". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 485 (4): 4703–4725. arXiv:1901.11297. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz345.

- ^ a b Goździewski, Krzysztof (September 2022). "The orbital architecture and stability of the μ Arae planetary system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 516 (4): 6096–6115. arXiv:2209.04542. doi:10.1093/mnras/stac2584.

- ^ Schütz, O.; et al. (2004). "A search for circumstellar dust disks with ADONIS". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 424 (2): 613–618. arXiv:astro-ph/0408530. Bibcode:2004A&A...424..613S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20034215. S2CID 25921357.

- ^ Canup, R.; Ward, W. (2006). "A common mass scaling for satellite systems of gaseous planets". Nature. 441 (7095): 834–839. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..834C. doi:10.1038/nature04860. PMID 16778883. S2CID 4327454.

- ^ Buccino, A.; et al. (2006). "Ultraviolet Radiation Constraints around the Circumstellar Habitable Zones". Icarus. 183 (2): 491–503. arXiv:astro-ph/0512291. Bibcode:2006Icar..183..491B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.03.007. S2CID 2241081.

External links

[edit]- GJ 691

- HR 6585

- Britt, Robert Roy (25 August 2004). "'Super Earth' Discovered at Nearby Star". Space.com. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- "Fourteen Times the Earth". European Southern Observatory. 25 August 2004. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- "Mu Ara: a system with 4 planets". Geneva Observatory. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- "Mu Arae". SolStation. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- Image Mu Arae

- Extrasolar Planet Interactions Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Rory Barnes & Richard Greenberg, Lunar and Planetary Lab, University of Arizona

Mu Arae

View on GrokipediaNomenclature

Traditional and catalog names

Mu Arae, Latinized from the Greek μ Arae, is the Bayer designation for a star in the southern constellation Ara, where it ranks as the eleventh-brightest member.[5] The designation uses the Greek letter mu (μ) prefixed to the genitive form Arae, reflecting its position in the Altar constellation visible primarily from the Southern Hemisphere.[6] The star appears in several modern astronomical catalogs under alternative identifiers, including HD 160691 from the Henry Draper Catalogue, HIP 86796 from the Hipparcos Catalogue, and HR 6585 from the Harvard Revised Catalogue.[7] These designations facilitate precise referencing in stellar databases and observations.[7] In 2015, as part of the International Astronomical Union's NameExoWorlds contest, the proper name Cervantes was officially approved for the star, drawing inspiration from the renowned Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, whose works influenced the naming of associated exoplanets. With an apparent visual magnitude of 5.15, Mu Arae is faintly visible to the naked eye from locations with dark skies, though it requires minimal light pollution for clear observation.[8]Planet designations

The exoplanets orbiting Mu Arae were initially designated with provisional lowercase letters following the established convention for extrasolar planets, where the first discovered planet is labeled "b" and subsequent ones receive sequential letters "c", "d", and so on, ultimately ordered by increasing semi-major axis once the system's architecture is better understood. This system, adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), ensures a standardized nomenclature during the early stages of discovery and characterization. In 2015, as part of the IAU's inaugural NameExoWorlds contest, the public participated in naming 31 exoplanets across 14 systems, including the four around Mu Arae, marking the first official opportunity for global involvement in exoplanet nomenclature.[9] The contest involved submissions from registered astronomical organizations, followed by a worldwide public vote concluding on October 31, 2015, with over 573,000 votes cast; winning names were approved by the IAU Working Group on Exoplanetary System Nomenclature to adhere to guidelines prohibiting mythological, historical, or cultural conflicts.[10] For Mu Arae, the accepted proposal originated from the Planetario de Pamplona in Spain, thematically linking the names to characters from Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote, in honor of the star's approved name Cervantes.[11] Under this scheme, the planets are now formally designated Mu Arae b (Quijote), Mu Arae c (Dulcinea), Mu Arae d (Rocinante), and Mu Arae e (Sancho), where Quijote refers to the novel's protagonist, Dulcinea to his idealized lady, Rocinante to his horse, and Sancho to his squire.[10][11] These proper names supplement the provisional designations and are used alongside them in scientific literature to provide cultural and historical context while maintaining precision.Stellar Characteristics

Physical properties

Mu Arae is classified as a G3IV–V star, signifying a yellow dwarf transitioning from the main-sequence phase toward subgiant status, with characteristics intermediate between a stable main-sequence G-type star and an evolving subgiant. The star possesses a mass of 1.10 ± 0.01 M⊙, a radius of 1.33 ± 0.02 R⊙, and a luminosity of ~1.8 L⊙, making it slightly more massive and larger than the Sun while emitting nearly twice its energy output.[1] These dimensions contribute to a higher surface brightness compared to solar values. Its effective temperature measures 5798 ± 33 K, surface gravity is log g ≈ 4.2 (in cgs units), and metallicity is [Fe/H] = 0.32 ± 0.01, reflecting an iron abundance roughly twice that of the Sun and indicating a metal-enriched composition conducive to enhanced stellar structure stability.[1] Located at a distance of 50.89 ± 0.07 light-years from the Solar System, as measured by the Gaia DR3 parallax of 64.0853 ± 0.0904 mas, Mu Arae is one of the closer Sun-like stars hosting a known planetary system. The star's projected rotational velocity is v sin i = 3.8 ± 0.2 km/s, consistent with a relatively slow rotation typical for older G-type stars, and its chromospheric activity level is low at log R′_HK = -5.03 ± 0.01, as derived from calcium H and K line measurements.[12][13]Age, evolution, and kinematics

Mu Arae has an estimated age of 5.7–8.0 Gyr (5.7 ± 0.6 Gyr as of 2022), derived from asteroseismic modeling and isochrone fitting that constrain its internal structure and evolutionary track.[1] This age determination aligns with independent estimates from isochrone fitting to its position in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram and gyrochronology based on its rotation period, though uncertainties arise from model assumptions about convective overshooting and helium abundance.[14] The evolutionary stage of Mu Arae remains debated, with its spectral classification as G3IV indicating a possible subgiant status, while other analyses favor a main-sequence G5V interpretation. Asteroseismic data reveal a large frequency separation of approximately 90 μHz, consistent with a star at the onset of the subgiant branch, where core hydrogen exhaustion has begun. Evidence from lithium abundance, measured at log ε(Li) ≈ 1.2, supports this slightly evolved state, as the depletion is greater than expected for a zero-age main-sequence star of similar mass but less than in fully convective subgiants.[14] Kinematically, Mu Arae exhibits a radial velocity of -9.42 ± 0.00 km/s and proper motion components of μ_α cos δ = -15.034 ± 0.084 mas/yr and μ_δ = -190.901 ± 0.065 mas/yr, as measured by Gaia DR3.[12] These values place the star in a Galactic orbit characteristic of the thin disk population, with low eccentricity (e ≈ 0.1) and pericentric and apocentric distances of roughly 6.5 kpc and 8.5 kpc, respectively, obtained through numerical integration of its space motion.[12] Future asteroseismic observations, potentially with space-based telescopes like PLATO, could refine the age and evolutionary status by resolving individual oscillation modes and reducing uncertainties in core composition.[14] This star's age implies long-term stability for its planetary system over billions of years.Planetary System

Discovery history

The discovery of exoplanets around Mu Arae began with the detection of Mu Arae b, a Jupiter-mass planet with an orbital period of approximately 645 days, announced in 2001 by the Anglo-Australian Planet Search team. This team utilized the Ultra-high Precision Radial velocity Explorer Spectrograph (UCLES) mounted on the 3.9-meter Anglo-Australian Telescope at Siding Spring Observatory to measure the star's radial velocity variations, revealing periodic signals indicative of a massive planetary companion. The observations achieved precision levels sufficient to detect velocity amplitudes on the order of tens of meters per second, marking an early success in identifying Jupiter-mass planets around Sun-like stars through the radial velocity method.[3] In 2004, two significant announcements expanded the known system, resolving ambiguities in the radial velocity data from the initial discovery. European astronomers using the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) spectrograph on the 3.6-meter ESO telescope at La Silla Observatory identified Mu Arae d, the first confirmed "hot Neptune"—a low-mass planet in a close orbit—based on high-cadence observations that disentangled its short-period signal from the longer ones.[15] Concurrently, observations with the High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer (HIRES) on the 10-meter Keck I telescope led to the detection of Mu Arae e, further clarifying the complex velocity curve through additional data points that highlighted interactions among multiple companions.[16] These efforts combined datasets from HARPS and HIRES, achieving radial velocity precisions around 3 m/s, which were crucial for isolating signals in a multi-planet scenario. Over 100 measurements from these and prior campaigns provided the temporal baseline needed to model the overlapping orbital influences. The four-planet configuration was confirmed in 2007 by independent research teams, solidifying Mu Arae as the second known multi-planet system with four companions after 55 Cancri and underscoring the challenges of disentangling superimposed radial velocity signals from co-orbiting bodies. Krzysztof Goździewski and colleagues employed N-body simulations to fit the combined radial velocity dataset, demonstrating dynamical stability for the proposed orbits. Similarly, Francesco Pepe's team, using extended HARPS observations, validated the model through self-consistent orbital solutions that accounted for gravitational perturbations.[4] This historical milestone highlighted the radial velocity technique's evolution, requiring extensive computational modeling to interpret data from stars hosting multiple planets. Subsequent studies, including 2022 analyses incorporating Hubble Space Telescope astrometry, have refined these orbital fits and placed upper limits on the planets' true masses (4–7 Jupiter masses for the giants) while confirming no additional massive companions, though orbital inclinations remain uncertain.[17]Individual planets

Mu Arae d is the innermost known planet in the system, orbiting at a semi-major axis of 0.09 AU with a period of 9.64 days and an eccentricity of approximately 0.16. Detected via high-precision radial velocity measurements, it has a minimum mass of 0.044 Jupiter masses (about 14 Earth masses), making it one of the lowest-mass exoplanets confirmed at the time of its discovery.[1] This places it in the hot Neptune category, with its close proximity to the star subjecting it to intense stellar radiation. Given its mass range and orbital distance, models suggest a composition dominated by rock and ice, overlaid with a hydrogen-helium envelope akin to Neptune's structure, though no direct measurements of radius or density are available due to the lack of transit detections.[18] Mu Arae e occupies an intermediate orbit at a semi-major axis of 0.921 AU, completing one revolution every 307.9 days with an eccentricity of approximately 0.09. Its minimum mass is 0.521 Jupiter masses, indicating a substantial gaseous envelope likely surrounding a core of heavier elements, characteristic of a Neptune-mass or transitional giant planet. Like the others, its mass is a lower bound derived from the radial velocity signal, as the orbital inclination remains unconstrained without astrometric or imaging confirmation.[1][18] Farther out, Mu Arae b serves as a Jupiter analog, with a minimum mass of 1.67 Jupiter masses, an orbital period of 645 days, a semi-major axis of 1.497 AU, and a modest eccentricity of approximately 0.04. This gas giant's parameters suggest a composition primarily of hydrogen and helium, similar to Jupiter, though its true mass and radius cannot be precisely determined absent inclination data or direct observations.[1][18] The outermost planet, Mu Arae c, has a minimum mass of 1.81 Jupiter masses and orbits at a semi-major axis of 5.235 AU over a period of 3,947 days with an eccentricity of approximately 0.02. As a cold Jupiter-mass world, it represents the most distant companion in the system, its radial velocity signature providing only the sin i-projected mass limit due to the absence of transit or direct imaging detections.[1][18] All four planets' masses are minimum values (m sin i) because radial velocity techniques measure the component of the stellar wobble along the line of sight, requiring knowledge of the orbital inclination for true masses; astrometric observations have yielded upper mass limits but no firm inclination constraints.[17]System architecture and stability

The Mu Arae planetary system comprises four planets with a configuration that includes a compact inner subsystem dominated by planets d and e, whose orbital periods of 9.64 days and 307.9 days yield a period ratio of approximately 32:1.[19] This inner pair is followed by planet b at 645 days, placing it in a near 2:1 mean-motion resonance with planet e (period ratio of 2.09).[19] The outermost planet c orbits with a period of 3,947 days, extending the system to about 5.2 AU and forming a period ratio of roughly 6.1:1 with planet b, suggestive of proximity to a 6:1 resonance.[19][20] The overall architecture reflects high planetary multiplicity across semi-major axes from ~0.09 AU (planet d) to ~5.2 AU (planet c), with moderate gaps between orbits that distinguish it from ultra-compact multi-planet systems like TRAPPIST-1.[20] These orbital elements, derived from radial velocity and astrometric data, indicate low eccentricities (ranging from ~0.02 for c to 0.16 for d) that contribute to the potential for long-term dynamical coherence.[19] Long-term stability analyses using N-body simulations demonstrate that the system remains dynamically stable for over 6.7 billion years, exceeding the estimated age of the host star, but only if mutual inclinations among the planets are at least ~20°.[20] Coplanar configurations lead to instability within 10^5 years, primarily driven by interactions involving planet e, whereas inclinations of 20°–90°—with a likely range of 20°–30°—ensure robustness even for planetary masses up to five times their minimum values (0.044 M_Jup for d, 0.521 M_Jup for e, 1.67 M_Jup for b, and 1.81 M_Jup for c).[19] These models highlight apsidal corotation possibilities in the inner subsystem and confirm no large-scale ejections or collisions over gigayear timescales. Despite extensive radial velocity searches, no additional planets have been confirmed beyond these four, and no significant updates to the stability models have emerged since 2022 (as of November 2025).[20] The system's dynamical packing, with its resonant near-misses and inclination-dependent equilibrium, underscores its resilience compared to less stable multi-planet configurations.[20]Habitability and biosignatures

The habitable zone (HZ) of Mu Arae, the orbital region where conditions might allow liquid surface water on a rocky planet, is estimated using stellar luminosity-dependent models. For Mu Arae's luminosity of approximately 1.75 L⊙, the conservative HZ extends from 1.25 to 2.15 AU, while the optimistic HZ ranges from 0.95 to 2.40 AU, accounting for potential greenhouse effects and atmospheric compositions that could expand viable conditions.[22] Mu Arae b, with a semi-major axis of about 1.50 AU, lies centrally within this zone, but its minimum mass of 1.67 M_Jup suggests it is a gas giant, limiting direct habitability to possible moons rather than the planet itself.[2] Habitability prospects for Mu Arae b face several challenges, including tidal locking risks for any close-in satellites, which could lead to extreme temperature contrasts between the day and night sides. The G3V host star emits ultraviolet (UV) radiation 1.5–2 times higher than the Sun's at equivalent distances, potentially causing significant atmospheric erosion through hydrodynamic escape on low-mass worlds or moons lacking strong magnetic protection. Additionally, the planet's likely gaseous envelope precludes a rocky surface, shifting focus to subsurface or atmospheric niches on potential satellites, though no such bodies have been detected. The inner planets Mu Arae d and e orbit too close to the star for liquid water stability. Mu Arae d, at 0.09 AU, receives roughly 300 times Earth's insolation, resulting in surface temperatures exceeding 1000 K and evaporative loss of any volatiles. Mu Arae e, at 0.92 AU, experiences about twice Earth's flux despite being near the HZ inner edge, but its minimum mass of 0.521 M_Jup indicates a gas giant incompatible with surface habitability.[2] Mu Arae c, with a semi-major axis of 5.2 AU, falls well outside the HZ, receiving only ~7% of Earth's insolation and likely maintaining frigid conditions. As a probable ice giant with a minimum mass of 1.81 M_Jup, it may support subsurface oceans on icy moons, analogous to Europa in our Solar System, where geothermal or radiogenic heating could sustain liquid water beneath thick ice layers.[2] Prospects for detecting biosignatures in the Mu Arae system remain limited, with no atmospheric characterizations achieved to date due to the planets' discovery via radial velocity rather than transit methods. Future observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) offer potential for indirect probes, such as high-resolution cross-correlation spectroscopy or nulling interferometry to search for molecular disequilibria (e.g., O₂, CH₄, or DMS) in the atmospheres of Mu Arae b or its hypothesized moons, though signal-to-noise challenges persist for non-transiting targets.[23][24]References

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.04542