Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stellar classification

View on WikipediaIn astronomy, stellar classification is the classification of stars based on their spectral characteristics. Electromagnetic radiation from the star is analyzed by splitting it with a prism or diffraction grating into a spectrum exhibiting the rainbow of colors interspersed with spectral lines. Each line indicates a particular chemical element or molecule, with the line strength indicating the abundance of that element. The strengths of the different spectral lines vary mainly due to the temperature of the photosphere, although in some cases there are true abundance differences. The spectral class of a star is a short code primarily summarizing the ionization state, giving an objective measure of the photosphere's temperature.

Most stars are currently classified under the Morgan–Keenan (MK) system using the letters O, B, A, F, G, K, and M, a sequence from the hottest (O type) to the coolest (M type). Each letter class is then subdivided using a numeric digit with 0 being hottest and 9 being coolest (e.g., A8, A9, F0, and F1 form a sequence from hotter to cooler). The sequence has been expanded with three classes for other stars that do not fit in the classical system: W, S and C. Some stellar remnants or objects of deviating mass have also been assigned letters: D for white dwarfs and L, T and Y for brown dwarfs (and exoplanets).

In the MK system, a luminosity class is added to the spectral class using Roman numerals. This is based on the width of certain absorption lines in the star's spectrum, which vary with the density of the atmosphere and so distinguish giant stars from dwarfs. Luminosity class 0 or Ia+ is used for hypergiants, class I for supergiants, class II for bright giants, class III for regular giants, class IV for subgiants, class V for main-sequence stars, class sd (or VI) for subdwarfs, and class D (or VII) for white dwarfs. The full spectral class for the Sun is then G2V, indicating a main-sequence star with a surface temperature around 5,800 K.

Conventional colour description

[edit]The conventional colour description takes into account only the peak of the stellar spectrum. In actuality, however, stars radiate in all parts of the spectrum. Because all spectral colours combined appear white, the actual apparent colours the human eye would observe are far lighter than the conventional colour descriptions would suggest. This characteristic of 'lightness' indicates that the simplified assignment of colours within the spectrum can be misleading. Excluding colour-contrast effects in dim light, in typical viewing conditions there are no green, cyan, indigo, or violet stars. "Yellow" dwarfs such as the Sun are white, "red" dwarfs are a deep shade of yellow/orange, and "brown" dwarfs do not literally appear brown, but hypothetically would appear dim red or grey/black to a nearby observer.

Modern classification

[edit]The modern classification system is known as the Morgan–Keenan (MK) classification. Each star is assigned a spectral class (from the older Harvard spectral classification, which did not include luminosity[1]) and a luminosity class using Roman numerals as explained below, forming the star's spectral type.

Other modern stellar classification systems, such as the UBV system, are based on color indices—the measured differences in three or more color magnitudes.[2] Those numbers are given labels such as "U−V" or "B−V", which represent the colors passed by two standard filters (e.g. Ultraviolet, Blue and Visual).

Harvard spectral classification

[edit]The Harvard system is a one-dimensional classification scheme by astronomer Annie Jump Cannon, who re-ordered and simplified the prior alphabetical system by Draper (see History). Stars are grouped according to their spectral characteristics by single letters of the alphabet, optionally with numeric subdivisions. Main-sequence stars vary in surface temperature from approximately 2,000 to 50,000 K, whereas more-evolved stars – in particular, newly-formed white dwarfs – can have surface temperatures above 100,000 K.[3] Physically, the classes indicate the temperature of the star's atmosphere and are normally listed from hottest to coldest.

| Class | Effective temperature |

Vega-relative chromaticity |

Chromaticity (D65) |

Main‑sequence mass[4][10](solar masses) | Main‑sequence radius[4][10](solar radii) | Main‑sequence luminosity[4][10](bolometric) | Hydrogen lines | Percentage of all main‑sequence stars[c][11] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | ≥ 33,000 K | blue | blue | ≥ 16 M☉ | ≥ 6.6 R☉ | ≥ 30,000 L☉ | Weak | 0.00003% |

| B | 10,000–33,000 K | bluish white | deep bluish white | 2.1–16 M☉ | 1.8–6.6 R☉ | 25–30,000 L☉ | Medium | 0.12% |

| A | 7,300–10,000 K | white | bluish white | 1.4–2.1 M☉ | 1.4–1.8 R☉ | 5–25 L☉ | Strong | 0.61% |

| F | 6,000–7,300 K | yellowish white | white | 1.04–1.4 M☉ | 1.15–1.4 R☉ | 1.5–5 L☉ | Medium | 3.0% |

| G | 5,300–6,000 K | yellow | yellowish white | 0.8–1.04 M☉ | 0.96–1.15 R☉ | 0.6–1.5 L☉ | Weak | 7.6% |

| K | 3,900–5,300 K | light orange | pale yellowish orange | 0.45–0.8 M☉ | 0.7–0.96 R☉ | 0.08–0.6 L☉ | Very weak | 12% |

| M | 2,300–3,900 K | Light orangish red | orangish red | 0.08–0.45 M☉ | ≤ 0.7 R☉ | ≤ 0.08 L☉ | Very weak | 76% |

The traditional mnemonic for remembering the order of the spectral type letters, from hottest to coolest, is "Oh, Be A Fine Guy/Girl: Kiss Me!".[12] Many alternative mnemonics have been proposed, in contests held by astronomy courses and organizations, but the traditional mnemonic remains the most popular.[13][14]

The spectral classes O through M, as well as other more specialized classes discussed later, are subdivided by Arabic numerals (0–9), where 0 denotes the hottest stars of a given class. For example, A0 denotes the hottest stars in class A and A9 denotes the coolest ones. Fractional numbers are allowed; for example, the star Mu Normae is classified as O9.7.[15] The Sun is classified as G2.[16]

The fact that the Harvard classification of a star indicated its surface or photospheric temperature (or more precisely, its effective temperature) was not fully understood until after its development, though by the time the first Hertzsprung–Russell diagram was formulated (by 1914), this was generally suspected to be true.[17] In the 1920s, the Indian physicist Meghnad Saha derived a theory of ionization by extending well-known ideas in physical chemistry pertaining to the dissociation of molecules to the ionization of atoms. First he applied it to the solar chromosphere, then to stellar spectra.[18]

Harvard astronomer Cecilia Payne then demonstrated that the O-B-A-F-G-K-M spectral sequence is actually a sequence in temperature.[19] Because the classification sequence predates our understanding that it is a temperature sequence, the placement of a spectrum into a given subtype, such as B3 or A7, depends upon (largely subjective) estimates of the strengths of absorption features in stellar spectra. As a result, these subtypes are not evenly divided into any sort of mathematically representable intervals.

Morgan–Keenan classification

[edit]The Yerkes spectral classification, also called the MK, or Morgan-Keenan (alternatively referred to as the MKK, or Morgan-Keenan-Kellman)[20][21] system from the authors' initials, is a system of stellar spectral classification introduced in 1943 by William Wilson Morgan, Philip C. Keenan, and Edith Kellman from Yerkes Observatory.[22] This two-dimensional (temperature and luminosity) classification scheme is based on spectral lines sensitive to stellar temperature and surface gravity, which is related to luminosity (whilst the Harvard classification is based on just surface temperature). Later, in 1953, after some revisions to the list of standard stars and classification criteria, the scheme was named the Morgan–Keenan classification, or MK,[23] which remains in use today.

Denser stars with higher surface gravity exhibit greater pressure broadening of spectral lines. The gravity, and hence the pressure, on the surface of a giant star is much lower than for a dwarf star because the radius of the giant is much greater than a dwarf of similar mass. Therefore, differences in the spectrum can be interpreted as luminosity effects and a luminosity class can be assigned purely from examination of the spectrum.

A number of different luminosity classes are distinguished, as listed in the table below.[24]

| Luminosity class | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 0 or Ia+ | hypergiants or extremely luminous supergiants | Cygnus OB2#12 – B3-4Ia+[25] |

| Ia | luminous supergiants | Eta Canis Majoris – B5Ia[26] |

| Iab | intermediate-size luminous supergiants | Gamma Cygni – F8Iab[27] |

| Ib | less luminous supergiants | Zeta Persei – B1Ib[28] |

| II | bright giants | Beta Leporis – G5II[29] |

| III | normal giants | Arcturus – K0III[30] |

| IV | subgiants | Gamma Cassiopeiae – B0.5IVpe[31] |

| V | main-sequence stars (dwarfs) | Achernar – B6Vep[28] |

| sd (prefix) or VI | subdwarfs | HD 149382 – sdB5 or B5VI[32] |

| D (prefix) or VII | white dwarfs[d] | van Maanen 2 – DZ8[33] |

Marginal cases are allowed; for example, a star may be either a supergiant or a bright giant, or may be in between the subgiant and main-sequence classifications. In these cases, two special symbols are used between the two luminosity classes:

- A slash (/) means that a star is either one class or the other.

- A hyphen (-) means that the star is in between the two classes.

For example, a star classified as A3-4III/IV would be in between spectral types A3 and A4, while being either a giant star or a subgiant.

Sub-dwarf classes have also been used: VI for sub-dwarfs (stars slightly less luminous than the main sequence).

Nominal luminosity class VII (and sometimes higher numerals) is now rarely used for white dwarf or "hot sub-dwarf" classes, since the temperature-letters of the main sequence and giant stars no longer apply to white dwarfs.

Occasionally, letters a and b are applied to luminosity classes other than supergiants; for example, a giant star slightly less luminous than typical may be given a luminosity class of IIIb, while a luminosity class IIIa indicates a star slightly brighter than a typical giant.[34]

A sample of extreme V stars with strong absorption in He II λ4686 spectral lines have been given the Vz designation. An example star is HD 93129 B.[35]

Spectral peculiarities

[edit]Additional nomenclature, in the form of lower-case letters, can follow the spectral type to indicate peculiar features of the spectrum.[36]

| Code | Spectral peculiarities for stars |

|---|---|

| : | uncertain spectral value[24] |

| ... | Undescribed spectral peculiarities exist |

| ! | Special peculiarity |

| comp | Composite spectrum[37] |

| e | Emission lines present[37] |

| [e] | "Forbidden" emission lines present |

| er | "Reversed" center of emission lines weaker than edges |

| eq | Emission lines with P Cygni profile |

| f | N III and He II emission[24] |

| f* | N IV 4058Å is stronger than the N III 4634Å, 4640Å, & 4642Å lines[38] |

| f+ | Si IV 4089Å & 4116Å are emitted, in addition to the N III line[38] |

| f? | C III 4647–4650–4652Å emission lines with comparable strength to the N III line[39] |

| (f) | N III emission, absence or weak absorption of He II |

| (f+) | [40] |

| ((f)) | Displays strong He II absorption accompanied by weak N III emissions[41] |

| ((f*)) | [40] |

| h | WR stars with hydrogen emission lines.[42] |

| ha | WR stars with hydrogen seen in both absorption and emission.[42] |

| He wk | Weak Helium lines |

| k | Spectra with interstellar absorption features |

| m | Enhanced metal features[37] |

| n | Broad ("nebulous") absorption due to spinning[37] |

| nn | Very broad absorption features[24] |

| neb | A nebula's spectrum mixed in[37] |

| p | Unspecified peculiarity, peculiar star.[e][37] |

| pq | Peculiar spectrum, similar to the spectra of novae |

| q | P Cygni profiles |

| s | Narrow ("sharp") absorption lines[37] |

| ss | Very narrow lines |

| sh | Shell star features[37] |

| var | Variable spectral feature[37] (sometimes abbreviated to "v") |

| wl | Weak lines[37] (also "w" & "wk") |

| Element symbol |

Abnormally strong spectral lines of the specified element(s)[37] |

| z | indicating an abnormally strong ionised helium line at 468.6 nm[35] |

For example, 59 Cygni is listed as spectral type B1.5Vnne,[43] indicating a spectrum with the general classification B1.5V, as well as very broad absorption lines and certain emission lines.

History

[edit]The reason for the odd arrangement of letters in the Harvard classification is historical, having evolved from the earlier Secchi classes and been progressively modified as understanding improved.

Secchi classes

[edit]During the 1860s and 1870s, pioneering stellar spectroscopist Angelo Secchi created the Secchi classes in order to classify observed spectra. By 1866, he had developed three classes of stellar spectra, shown in the table below.[44][45][46]

In the late 1890s, this classification began to be superseded by the Harvard classification, which is discussed in the remainder of this article.[47][48][49]

| Class number | Secchi class description |

|---|---|

| Secchi class I | White and blue stars with broad heavy hydrogen lines, such as Vega and Altair. This includes the modern class A and early class F. |

| Secchi class I (Orion subtype) |

A subtype of Secchi class I with narrow lines in place of wide bands, such as Rigel and Bellatrix. In modern terms, this corresponds to early B-type stars |

| Secchi class II | Yellow stars – hydrogen less strong, but evident metallic lines, such as the Sun, Arcturus, and Capella. This includes the modern classes G and K as well as late class F. |

| Secchi class III | Orange to red stars with complex band spectra, such as Betelgeuse and Antares. This corresponds to the modern class M. |

| Secchi class IV | In 1868, he discovered carbon stars, which he put into a distinct group:[50] Red stars with significant carbon bands and lines, corresponding to modern classes C and S. |

| Secchi class V | In 1877, he added a fifth class:[51] Emission-line stars, such as Gamma Cassiopeiae and Sheliak, which are in modern class Be. In 1891, Edward Charles Pickering proposed that class V should correspond to the modern class O (which then included Wolf–Rayet stars) and stars within planetary nebulae.[52] |

The Roman numerals used for Secchi classes should not be confused with the completely unrelated Roman numerals used for Yerkes luminosity classes and the proposed neutron star classes.

Draper system

[edit]| Secchi | Draper | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| I | A, B, C, D | Hydrogen lines dominant |

| II | E, F, G, H, I, K, L | |

| III | M | |

| IV | N | Did not appear in the catalogue |

| V | O | Included Wolf–Rayet spectra with bright lines, sometimes classified separately as type W[55] |

| V | P | Planetary nebulae |

| Q | Other spectra | |

| Classes carried through into the MK system are in bold. | ||

After the death of her husband, Mary Anna Draper began to fund the creation of the Harvard Plate Stacks and the study of these plates at the Harvard College Observatory. The director of the Observatory, Edward C. Pickering began to hire pioneering female astronomers collectively known as the Harvard Computers. Thought they would study many different astronomical subjects, an early result of this work was the first edition of The Henry Draper Memorial Catalogue of Stellar Spectra, first published in 1890. Williamina Fleming classified most of the spectra in the first edition of the catalogue and is credited with classifying over 10,000 featured stars and discovering 10 novae and more than 200 variable stars.[56] With the help of the Harvard Computers, especially Williamina Fleming, the first iteration of the Henry Draper catalogue was devised to replace the Roman-numeral scheme established by Angelo Secchi.[57]

The catalogue used a scheme in which the previously used Secchi classes (I to V) were subdivided into more specific classes, given letters from A to P. Also, the letter Q was used for stars not fitting into any other class.[53][54] Fleming worked with Pickering to differentiate 17 different classes based on the intensity of hydrogen spectral lines, which causes variation in the wavelengths emanated from stars and results in variation in color appearance. The spectra in class A tended to produce the strongest hydrogen absorption lines while spectra in class O produced virtually no visible lines. The lettering system displayed the gradual decrease in hydrogen absorption in the spectral classes when moving down the alphabet. This classification system was later modified by Annie Jump Cannon and Antonia Maury to produce the Harvard spectral classification scheme.[56][58]

The old Harvard system (1897)

[edit]In 1897, another astronomer at Harvard, Antonia Maury, placed the Orion subtype of Secchi class I ahead of the remainder of Secchi class I, thus placing the modern type B ahead of the modern type A. She was the first to do so, although she did not use lettered spectral types, but rather a series of twenty-two types numbered from I–XXII.[59][60]

| Groups | Summary |

|---|---|

| I−V | included 'Orion type' stars that displayed an increasing strength in hydrogen absorption lines from group I to group V |

| VI | acted as an intermediate between the 'Orion type' and Secchi type I group |

| VII−XI | were Secchi's type 1 stars, with decreasing strength in hydrogen absorption lines from groups VII−XI |

| XIII−XVI | included Secchi type 2 stars with decreasing hydrogen absorption lines and increasing solar-type metallic lines |

| XVII−XX | included Secchi type 3 stars with increasing spectral lines |

| XXI | included Secchi type 4 stars |

| XXII | included Wolf–Rayet stars |

Because the 22 Roman numeral groupings did not account for additional variations in spectra, three additional divisions were made to further specify differences: Lowercase letters were added to differentiate relative line appearance in spectra; the lines were defined as:[61]

- (a): average width

- (b): hazy

- (c): sharp

Antonia Maury published her own stellar classification catalogue in 1897 called "Spectra of Bright Stars Photographed with the 11 inch Draper Telescope as Part of the Henry Draper Memorial", which included 4,800 photographs and Maury's analyses of 681 bright northern stars. This was the first instance in which a woman was credited for an observatory publication.[62]

The current Harvard system (1912)

[edit]In 1901, Annie Jump Cannon returned to the lettered types, but dropped all letters except O, B, A, F, G, K, M, and N used in that order, as well as P for planetary nebulae and Q for some peculiar spectra. She also used types such as B5A for stars halfway between types B and A, F2G for stars one fifth of the way from F to G, and so on.[63][64]

Finally, by 1912, Cannon had changed the types B, A, B5A, F2G, etc. to B0, A0, B5, F2, etc.[65][66] This is essentially the modern form of the Harvard classification system. This system was developed through the analysis of spectra on photographic plates, which could convert light emanated from stars into a readable spectrum.[67]

Mount Wilson classes

[edit]A luminosity classification known as the Mount Wilson system was used to distinguish between stars of different luminosities.[68][69][70] This notation system is still sometimes seen on modern spectra.[71]

- sd: subdwarf

- d: dwarf

- sg: subgiant

- g: giant

- c: supergiant

Spectral types

[edit]The stellar classification system is taxonomic, based on type specimens, similar to classification of species in biology: The categories are defined by one or more standard stars for each category and sub-category, with an associated description of the distinguishing features.[72]

"Early" and "late" nomenclature

[edit]Stars are often referred to as early or late types. "Early" is a synonym for hotter, while "late" is a synonym for cooler.

Depending on the context, "early" and "late" may be absolute or relative terms. "Early" as an absolute term would therefore refer to O or B, and possibly A stars. As a relative reference it relates to stars hotter than others, such as "early K" being perhaps K0, K1, K2 and K3.

"Late" is used in the same way, with an unqualified use of the term indicating stars with spectral types such as K and M, but it can also be used for stars that are cool relative to other stars, as in using "late G" to refer to G7, G8, and G9.

In the relative sense, "early" means a lower Arabic numeral following the class letter, and "late" means a higher number.

This obscure terminology is a hold-over from a late nineteenth century model of stellar evolution, which supposed that stars were powered by gravitational contraction via the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism, which is now known to not apply to main-sequence stars. If that were true, then stars would start their lives as very hot "early-type" stars and then gradually cool down into "late-type" stars. This mechanism provided ages of the Sun that were much smaller than what is observed in the geologic record, and was rendered obsolete by the discovery that stars are powered by nuclear fusion.[73] The terms "early" and "late" were carried over, beyond the demise of the model they were based on.

Class O

[edit]

O-type stars are very hot and extremely luminous, with most of their radiated output in the ultraviolet range. These are the rarest of all main-sequence stars. About 1 in 3,000,000 (0.00003%) of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are O-type stars.[c][11] Some of the most massive stars lie within this spectral class. O-type stars frequently have complicated surroundings that make measurement of their spectra difficult.

O-type spectra formerly were defined by the ratio of the strength of the He II λ4541 relative to that of He I λ4471, where λ is the radiation wavelength. Spectral type O7 was defined to be the point at which the two intensities are equal, with the He I line weakening towards earlier types. Type O3 was, by definition, the point at which said line disappears altogether, although it can be seen very faintly with modern technology. Due to this, the modern definition uses the ratio of the nitrogen line N IV λ4058 to N III λλ4634-40-42.[74]

O-type stars have dominant lines of absorption and sometimes emission for He II lines, prominent ionized (Si IV, O III, N III, and C III) and neutral helium lines, strengthening from O5 to O9, and prominent hydrogen Balmer lines, although not as strong as in later types. Higher-mass O-type stars do not retain extensive atmospheres due to the extreme velocity of their stellar wind, which may reach 2,000 km/s. Because they are so massive, O-type stars have very hot cores and burn through their hydrogen fuel very quickly, so they are the first stars to leave the main sequence.

When the MKK classification scheme was first described in 1943, the only subtypes of class O used were O5 to O9.5.[75] The MKK scheme was extended to O9.7 in 1971[76] and O4 in 1978,[77] and new classification schemes that add types O2, O3, and O3.5 have subsequently been introduced.[78]

Example spectral standards:[72]

- O7V – S Monocerotis

- O9V – 10 Lacertae

Class B

[edit]

B-type stars are very luminous and blue. Their spectra have neutral helium lines, which are most prominent at the B2 subclass, and moderate hydrogen lines. As O- and B-type stars are so energetic, they only live for a relatively short time. Thus, due to the low probability of kinematic interaction during their lifetime, they are unable to stray far from the area in which they formed, apart from runaway stars.

The transition from class O to class B was originally defined to be the point at which the He II λ4541 disappears. However, with modern equipment, the line is still apparent in the early B-type stars. Today for main-sequence stars, the B class is instead defined by the intensity of the He I violet spectrum, with the maximum intensity corresponding to class B2. For supergiants, lines of silicon are used instead; the Si IV λ4089 and Si III λ4552 lines are indicative of early B. At mid-B, the intensity of the latter relative to that of Si II λλ4128-30 is the defining characteristic, while for late B, it is the intensity of Mg II λ4481 relative to that of He I λ4471.[74]

These stars tend to be found in their originating OB associations, which are associated with giant molecular clouds. The Orion OB1 association occupies a large portion of a spiral arm of the Milky Way and contains many of the brighter stars of the constellation Orion. About 1 in 800 (0.125%) of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are B-type main-sequence stars.[c][11] B-type stars are relatively uncommon and the closest is Regulus, at around 80 light years.[79]

Massive yet non-supergiant stars known as Be stars have been observed to show one or more Balmer lines in emission, with the hydrogen-related electromagnetic radiation series projected out by the stars being of particular interest. Be stars are generally thought to feature unusually strong stellar winds, high surface temperatures, and significant attrition of stellar mass as the objects rotate at a curiously rapid rate.[80]

Objects known as B[e] stars – or B(e) stars for typographic reasons – possess distinctive neutral or low ionisation emission lines that are considered to have forbidden mechanisms, undergoing processes not normally allowed under current understandings of quantum mechanics.

Example spectral standards:[72]

- B0V – Upsilon Orionis

- B0Ia – Alnilam

- B2Ia – Chi2 Orionis

- B2Ib – 9 Cephei

- B3V – Alkaid

- B3V – Haedus

- B3Ia – Omicron2 Canis Majoris

- B5Ia – Aludra

- B8Ia – Rigel

Class A

[edit]

A-type stars are among the more common naked eye stars, and are white or bluish-white. They have strong hydrogen lines, at a maximum by A0, and also lines of ionized metals (Fe II, Mg II, Si II) at a maximum at A5. The presence of Ca II lines is notably strengthening by this point. About 1 in 160 (0.625%) of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are A-type stars,[c][11] which includes 9 stars within 15 parsecs.[81]

Example spectral standards:[72]

- A0Van – Phecda

- A0Va – Vega

- A0Ib – Eta Leonis

- A0Ia – HD 21389

- A1V – Sirius A

- A2Ia – Deneb

- A3Va – Fomalhaut

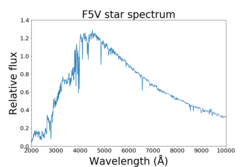

Class F

[edit]

F-type stars have strengthening spectral lines H and K of Ca II. Neutral metals (Fe I, Cr I) beginning to gain on ionized metal lines by late F. Their spectra are characterized by the weaker hydrogen lines and ionized metals. Their color is white. About 1 in 33 (3.03%) of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are F-type stars,[c][11] including 1 star Procyon A within 20 ly.[82]

Example spectral standards:[72][83][84][85][86]

- F0IIIa – Adhafera

- F0Ib – Arneb

- F1V - 37 Ursae Majoris

- F2V – 78 Ursae Majoris

- F7V - Iota Piscium

- F9V - Zavijava

- F9V - HD 10647

Class G

[edit]

G-type stars, including the Sun,[16] have prominent spectral lines H and K of Ca II, which are most pronounced at G2. They have even weaker hydrogen lines than F, but along with the ionized metals, they have neutral metals. There is a prominent spike in the G band of CN molecules. Class G main-sequence stars make up about 7.5%, nearly one in thirteen, of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood. There are 21 G-type stars within 10pc.[c][11]

Class G contains the "Yellow Evolutionary Void".[87] Supergiant stars often swing between O or B (blue) and K or M (red). While they do this, they do not stay for long in the unstable yellow supergiant class.

Example spectral standards:[72]

- G0V – Chara

- G0IV – Muphrid

- G0Ib – Sadalsuud

- G2V – Sun

- G5V – Kappa1 Ceti

- G5IV – Mu Herculis

- G5Ib – 9 Pegasi

- G8V – 61 Ursae Majoris

- G8IV – Alshain

- G8IIIa – Kappa Geminorum

- G8IIIab – Vindemiatrix

- G8Ib – Mebsuta

Class K

[edit]

K-type stars are orangish stars that are slightly cooler than the Sun. They make up about 12% of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood.[c][11] There are also giant K-type stars, which range from hypergiants like RW Cephei, to giants and supergiants, such as Arcturus, whereas orange dwarfs, like Alpha Centauri B, are main-sequence stars.

They have extremely weak hydrogen lines, if those are present at all, and mostly neutral metals (Mn I, Fe I, Si I). By late K, molecular bands of titanium oxide become present. Mainstream theories (those rooted in lower harmful radioactivity and star longevity) would thus suggest such stars have the optimal chances of heavily evolved life developing on orbiting planets (if such life is directly analogous to Earth's) due to a broad habitable zone yet much lower harmful periods of emission compared to those with the broadest such zones.[88][89]

Example spectral standards:[72]

- K0V – Alsafi

- K0III – Pollux

- K0III – Aljanah

- K2V – Ran

- K2III – Kappa Ophiuchi

- K3III – Rho Boötis

- K5V – 61 Cygni A

- K5III – Eltanin

Class M

[edit]

Class M stars are by far the most common. About 76% of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are class M stars.[c][f][11] However, class M main-sequence stars (red dwarfs) have such low luminosities that none are bright enough to be seen with the unaided eye, unless under exceptional conditions. The brightest-known M class main-sequence star is Lacaille 8760, class M0V, with magnitude 6.7 (the limiting magnitude for typical naked-eye visibility under good conditions being typically quoted as 6.5), and it is extremely unlikely that any brighter examples will be found.

Although most class M stars are red dwarfs, most of the largest-known supergiant stars in the Milky Way are class M stars, such as VY Canis Majoris, VV Cephei, Antares, and Betelgeuse. Furthermore, some larger, hotter brown dwarfs are late class M, usually in the range of M6.5 to M9.5.

The spectrum of a class M star contains lines from oxide molecules (in the visible spectrum, especially TiO) and all neutral metals, but absorption lines of hydrogen are usually absent. TiO bands can be strong in class M stars, usually dominating their visible spectrum by about M5. Vanadium(II) oxide bands become present by late M.

Example spectral standards:[72]

- M3V – Gliese 581

- M0IIIa – Mirach

- M2III – Chi Pegasi

- M1-M2Ia-Iab – Betelgeuse

- M2Ia – Mu Cephei ("Herschel's garnet")

Extended spectral types

[edit]A number of new spectral types have been taken into use from newly discovered types of stars.[90]

Hot blue emission star classes

[edit]

Spectra of some very hot and bluish stars exhibit marked emission lines from carbon or nitrogen, or sometimes oxygen.

Class WR (or W): Wolf–Rayet

[edit]

Once included as type O stars, the Wolf–Rayet stars of class W[92] or WR are notable for spectra lacking hydrogen lines. Instead their spectra are dominated by broad emission lines of highly ionized helium, nitrogen, carbon, and sometimes oxygen. They are thought to mostly be dying supergiants with their hydrogen layers blown away by stellar winds, thereby directly exposing their hot helium shells. Class WR is further divided into subclasses according to the relative strength of nitrogen and carbon emission lines in their spectra (and outer layers).[42]

WR spectra range is listed below:[93][94]

- WN[42] – spectrum dominated by N III-V and He I-II lines

- WNE (WN2 to WN5 with some WN6) – hotter or "early"

- WNL (WN7 to WN9 with some WN6) – cooler or "late"

- Extended WN classes WN10 and WN11 sometimes used for the Ofpe/WN9 stars[42]

- h tag used (e.g. WN9h) for WR with hydrogen emission and ha (e.g. WN6ha) for both hydrogen emission and absorption

- WN/C – WN stars plus strong C IV lines, intermediate between WN and WC stars[42]

- WC[42] – spectrum with strong C II-IV lines

- WCE (WC4 to WC6) – hotter or "early"

- WCL (WC7 to WC9) – cooler or "late"

- WO (WO1 to WO4) – strong O VI lines, extremely rare, extension of the WCE class into incredibly hot temperatures (up to 200 kK or more)

Although the central stars of most planetary nebulae (CSPNe) show O-type spectra,[95] around 10% are hydrogen-deficient and show WR spectra.[96] These are low-mass stars and to distinguish them from the massive Wolf–Rayet stars, their spectra are enclosed in square brackets: e.g. [WC]. Most of these show [WC] spectra, some [WO], and very rarely [WN].

Slash stars

[edit]The slash stars are O-type stars with WN-like lines in their spectra. The name "slash" comes from their printed spectral type having a slash in it (e.g. "Of/WNL")[74]).

There is a secondary group found with these spectra, a cooler, "intermediate" group designated "Ofpe/WN9".[74] These stars have also been referred to as WN10 or WN11, but that has become less popular with the realisation of the evolutionary difference from other Wolf–Rayet stars. Recent discoveries of even rarer stars have extended the range of slash stars as far as O2-3.5If*/WN5-7, which are even hotter than the original "slash" stars.[97]

Magnetic O stars

[edit]They are O stars with strong magnetic fields. Designation is Of?p.[74]

Cool red and brown dwarf classes

[edit]The new spectral types L, T, and Y were created to classify infrared spectra of cool stars. This includes both red dwarfs and brown dwarfs that are very faint in the visible spectrum.[98]

Brown dwarfs, stars that do not undergo hydrogen fusion, cool as they age and so progress to later spectral types. Brown dwarfs start their lives with M-type spectra and will cool through the L, T, and Y spectral classes, faster the less massive they are; the highest-mass brown dwarfs cannot have cooled to Y or even T dwarfs within the age of the universe. Because this leads to an unresolvable overlap between spectral types' effective temperature and luminosity for some masses and ages of different L-T-Y types, no distinct temperature or luminosity values can be given.[10]

Class L

[edit]

Class L dwarfs get their designation because they are cooler than M stars and L is the remaining letter alphabetically closest to M. Some of these objects have masses large enough to support hydrogen fusion and are therefore stars, but most are of substellar mass and are therefore brown dwarfs. They are a very dark red in color and brightest in infrared. Their atmosphere is cool enough to allow metal hydrides and alkali metals to be prominent in their spectra.[99][100][101]

Due to low surface gravity in giant stars, TiO- and VO-bearing condensates never form. Thus, L-type stars larger than dwarfs can never form in an isolated environment. However, it may be possible for these L-type supergiants to form through stellar collisions, an example of which is V838 Monocerotis while in the height of its luminous red nova eruption.

Class T

[edit]

Class T dwarfs are cool brown dwarfs with surface temperatures between approximately 550 and 1,300 K (277 and 1,027 °C; 530 and 1,880 °F). Their emission peaks in the infrared. Methane is prominent in their spectra.[99][100]

Study of the number of proplyds (protoplanetary disks, clumps of gas in nebulae from which stars and planetary systems are formed) indicates that the number of stars in the galaxy should be several orders of magnitude higher than what was previously conjectured. It is theorized that these proplyds are in a race with each other. The first one to form will become a protostar, which are very violent objects and will disrupt other proplyds in the vicinity, stripping them of their gas. The victim proplyds will then probably go on to become main-sequence stars or brown dwarfs of the L and T classes, which are quite invisible to us.[102]

Class Y

[edit]

Brown dwarfs of spectral class Y are cooler than those of spectral class T and have qualitatively different spectra from them. A total of 17 objects have been placed in class Y as of August 2013.[103] Although such dwarfs have been modelled[104] and detected within forty light-years by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE)[90][105][106][107][108] there is no well-defined spectral sequence yet and no prototypes. Nevertheless, several objects have been proposed as spectral classes Y0, Y1, and Y2.[109]

The spectra of these prospective Y objects display absorption around 1.55 micrometers.[110] Delorme et al. have suggested that this feature is due to absorption from ammonia, and that this should be taken as the indicative feature for the T-Y transition.[110][111] In fact, this ammonia-absorption feature is the main criterion that has been adopted to define this class.[109] However, this feature is difficult to distinguish from absorption by water and methane,[110] and other authors have stated that the assignment of class Y0 is premature.[112]

The latest brown dwarf proposed for the Y spectral type, WISE 1828+2650, is a > Y2 dwarf with an effective temperature originally estimated around 300 K, the temperature of the human body.[105][106][113] Parallax measurements have, however, since shown that its luminosity is inconsistent with it being colder than ~400 K. The coolest Y dwarf currently known is WISE 0855−0714 with an approximate temperature of 250 K, and a mass just seven times that of Jupiter.[114]

The mass range for Y dwarfs is 9–25 Jupiter masses, but young objects might reach below one Jupiter mass (although they cool to become planets), which means that Y class objects straddle the 13 Jupiter mass deuterium-fusion limit that marks the current IAU division between brown dwarfs and planets.[109]

Peculiar brown dwarfs

[edit]| Symbols used for peculiar brown dwarfs | |

|---|---|

| pec | This suffix stands for "peculiar" (e.g. L2pec).[115] |

| sd | This prefix (e.g. sdL0) stands for subdwarf and indicates a low metallicity and blue color[116] |

| β | Objects with the beta (β) suffix (e.g. L4β) have an intermediate surface gravity.[117] |

| γ | Objects with the gamma (γ) suffix (e.g. L5γ) have a low surface gravity.[117] |

| red | The red suffix (e.g. L0red) indicates objects without signs of youth, but high dust content.[118] |

| blue | The blue suffix (e.g. L3blue) indicates unusual blue near-infrared colors for L-dwarfs without obvious low metallicity.[119] |

Young brown dwarfs have low surface gravities because they have larger radii and lower masses compared to the field stars of similar spectral type. These sources are marked by a letter beta (β) for intermediate surface gravity and gamma (γ) for low surface gravity. Indication for low surface gravity are weak CaH, KI and NaI lines, as well as strong VO line.[117] Alpha (α) stands for normal surface gravity and is usually dropped. Sometimes an extremely low surface gravity is denoted by a delta (δ).[119] The suffix "pec" stands for peculiar. The peculiar suffix is still used for other features that are unusual and summarizes different properties, indicative of low surface gravity, subdwarfs and unresolved binaries.[120] The prefix sd stands for subdwarf and only includes cool subdwarfs. This prefix indicates a low metallicity and kinematic properties that are more similar to halo stars than to disk stars.[116] Subdwarfs appear bluer than disk objects.[121] The red suffix describes objects with red color, but an older age. This is not interpreted as low surface gravity, but as a high dust content.[118][119] The blue suffix describes objects with blue near-infrared colors that cannot be explained with low metallicity. Some are explained as L+T binaries, others are not binaries, such as 2MASS J11263991−5003550 and are explained with thin and/or large-grained clouds.[119]

Late giant carbon-star classes

[edit]Carbon-stars are stars whose spectra indicate production of carbon – a byproduct of triple-alpha helium fusion. With increased carbon abundance, and some parallel s-process heavy element production, the spectra of these stars become increasingly deviant from the usual late spectral classes G, K, and M. Equivalent classes for carbon-rich stars are S and C.

The giants among those stars are presumed to produce this carbon themselves, but some stars in this class are double stars, whose odd atmosphere is suspected of having been transferred from a companion that is now a white dwarf, when the companion was a carbon-star.

Class C

[edit]

Originally classified as R and N stars, these are also known as carbon stars. These are red giants, near the end of their lives, in which there is an excess of carbon in the atmosphere. The old R and N classes ran parallel to the normal classification system from roughly mid-G to late M. These have more recently been remapped into a unified carbon classifier C with N0 starting at roughly C6. Another subset of cool carbon stars are the C–J-type stars, which are characterized by the strong presence of molecules of 13 CN in addition to those of 12 CN.[122] A few main-sequence carbon stars are known, but the overwhelming majority of known carbon stars are giants or supergiants. There are several subclasses:

- C-R – Formerly its own class (R) representing the carbon star equivalent of late G- to early K-type stars.

- C-N – Formerly its own class representing the carbon star equivalent of late K- to M-type stars.

- C-J – A subtype of cool C stars with a high content of 13C.

- C-H – Population II analogues of the C-R stars.

- C-Hd – Hydrogen-deficient carbon stars, similar to late G supergiants with CH and C2 bands added.

Class S

[edit]Class S stars form a continuum between class M stars and carbon stars. Those most similar to class M stars have strong ZrO absorption bands analogous to the TiO bands of class M stars, whereas those most similar to carbon stars have strong sodium D lines and weak C2 bands.[123] Class S stars have excess amounts of zirconium and other elements produced by the s-process, and have more similar carbon and oxygen abundances to class M or carbon stars. Like carbon stars, nearly all known class S stars are asymptotic-giant-branch stars.

The spectral type is formed by the letter S and a number between zero and ten. This number corresponds to the temperature of the star and approximately follows the temperature scale used for class M giants. The most common types are S3 to S5. The non-standard designation S10 has only been used for the star Chi Cygni when at an extreme minimum.

The basic classification is usually followed by an abundance indication, following one of several schemes: S2,5; S2/5; S2 Zr4 Ti2; or S2*5. A number following a comma is a scale between 1 and 9 based on the ratio of ZrO and TiO. A number following a slash is a more-recent but less-common scheme designed to represent the ratio of carbon to oxygen on a scale of 1 to 10, where a 0 would be an MS star. Intensities of zirconium and titanium may be indicated explicitly. Also occasionally seen is a number following an asterisk, which represents the strength of the ZrO bands on a scale from 1 to 5.

Classes MS and SC: Intermediate carbon-related classes

[edit]In between the M and S classes, border cases are named MS stars. In a similar way, border cases between the S and C-N classes are named SC or CS. The sequence M → MS → S → SC → C-N is hypothesized to be a sequence of increased carbon abundance with age for carbon stars in the asymptotic giant branch.

White dwarf classifications

[edit]The class D (for Degenerate) is the modern classification used for white dwarfs—low-mass stars that are no longer undergoing nuclear fusion and have shrunk to planetary size, slowly cooling down. Class D is further divided into spectral types DA, DB, DC, DO, DQ, DX, and DZ. The letters are not related to the letters used in the classification of other stars, but instead indicate the composition of the white dwarf's visible outer layer or atmosphere.

The white dwarf types are as follows:[124][125]

- DA – a hydrogen-rich atmosphere or outer layer, indicated by strong Balmer hydrogen spectral lines.

- DB – a helium-rich atmosphere, indicated by neutral helium, He I, spectral lines.

- DO – a helium-rich atmosphere, indicated by ionized helium, He II, spectral lines.

- DQ – a carbon-rich atmosphere, indicated by atomic or molecular carbon lines.

- DZ – a metal-rich atmosphere, indicated by metal spectral lines (a merger of the obsolete white dwarf spectral types, DG, DK, and DM).

- DC – no strong spectral lines indicating one of the above categories.

- DX – spectral lines are insufficiently clear to classify into one of the above categories.

The type is followed by a number giving the white dwarf's surface temperature. This number is a rounded form of 50400/Teff, where Teff is the effective surface temperature, measured in kelvins. Originally, this number was rounded to one of the digits 1 through 9, but more recently fractional values have started to be used, as well as values below 1 and above 9.(For example DA1.5 for IK Pegasi B)[124][126]

Two or more of the type letters may be used to indicate a white dwarf that displays more than one of the spectral features above.[124]

Extended white dwarf spectral types

[edit]

- DAB – a hydrogen- and helium-rich white dwarf displaying neutral helium lines

- DAO – a hydrogen- and helium-rich white dwarf displaying ionized helium lines

- DAZ – a hydrogen-rich metallic white dwarf

- DBZ – a helium-rich metallic white dwarf

A different set of spectral peculiarity symbols are used for white dwarfs than for other types of stars:[124]

| Code | Spectral peculiarities for stars |

|---|---|

| P | Magnetic white dwarf with detectable polarization |

| E | Emission lines present |

| H | Magnetic white dwarf without detectable polarization |

| V | Variable |

| PEC | Spectral peculiarities exist |

Luminous blue variables

[edit]Luminous blue variables (LBVs) are rare, massive and evolved stars that show unpredictable and sometimes dramatic variations in their spectra and brightness. During their "quiescent" states, they are usually similar to B-type stars, although with unusual spectral lines. During outbursts, they are more similar to F-type stars, with significantly lower temperatures. Many papers treat LBV as its own spectral type.[127][128]

Spectral types of non-single objects: Classes P and Q

[edit]Finally, the classes P and Q are left over from the system developed by Cannon for the Henry Draper Catalogue. They are occasionally used for certain objects, not associated with a single star: Type P objects are stars within planetary nebulae (typically young white dwarfs or hydrogen-poor M giants); type Q objects are novae.[citation needed]

Stellar remnants

[edit]Stellar remnants are objects associated with the death of stars. Included in the category are white dwarfs, and as can be seen from the radically different classification scheme for class D, stellar remnants are difficult to fit into the MK system.

The Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, which the MK system is based on, is observational in nature so these remnants cannot easily be plotted on the diagram, or cannot be placed at all. Old neutron stars are relatively small and cold, and would fall on the far right side of the diagram. Planetary nebulae are dynamic and tend to quickly fade in brightness as the progenitor star transitions to the white dwarf branch. If shown, a planetary nebula would be plotted to the right of the diagram's upper right quadrant. A black hole emits no visible light of its own, and therefore would not appear on the diagram.[129]

A classification system for neutron stars using Roman numerals has been proposed: type I for less massive neutron stars with low cooling rates, type II for more massive neutron stars with higher cooling rates, and a proposed type III for more massive neutron stars (possible exotic star candidates) with higher cooling rates.[130] The more massive a neutron star is, the higher neutrino flux it carries. These neutrinos carry away so much heat energy that after only a few years the temperature of an isolated neutron star falls from the order of billions to only around a million Kelvin. This proposed neutron star classification system is not to be confused with the earlier Secchi spectral classes and the Yerkes luminosity classes.

Replaced spectral classes

[edit]Several spectral types, all previously used for non-standard stars in the mid-20th century, have been replaced during revisions of the stellar classification system. They may still be found in old editions of star catalogs: R and N have been subsumed into the new C class as C-R and C-N.

Stellar classification, habitability, and the search for life

[edit]While humans may eventually be able to colonize any kind of stellar habitat, this section will address the probability of life arising around other stars.

Stability, luminosity, and lifespan are all factors in stellar habitability. Humans know of only one star that hosts life, the G-class Sun, a star with an abundance of heavy elements and low variability in brightness. The Solar System is also unlike many stellar systems in that it only contains one star (see Habitability of binary star systems).

Working from these constraints and the problems of having an empirical sample set of only one, the range of stars that are predicted to be able to support life is limited by a few factors. Of the main-sequence star types, stars more massive than 1.5 times that of the Sun (spectral types O, B, and A) age too quickly for advanced life to develop (using Earth as a guideline). On the other extreme, dwarfs of less than half the mass of the Sun (spectral type M) are likely to tidally lock planets within their habitable zone, along with other problems (see Habitability of red dwarf systems).[131] While there are many problems facing life on red dwarfs, many astronomers continue to model these systems due to their sheer numbers and longevity.

For these reasons NASA's Kepler Mission is searching for habitable planets at nearby main-sequence stars that are less massive than spectral type A but more massive than type M—making the most probable stars to host life dwarf stars of types F, G, and K.[131]

See also

[edit]- Astrograph – Type of telescope

- Guest star – Ancient Chinese name for cataclysmic variable stars

- Spectral signature – Variation of reflectance or emittance of a material with respect to wavelengths

- Star count – Bookkeeping survey of stars, survey of stars

- Stellar dynamics – Branch of astrophysics

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is the relative color of the star if Vega, generally considered a bluish star, is used as a standard for "white".

- ^ Chromaticity can vary significantly within a class; for example, the Sun (a G2 star) is white, while a G9 star is yellow.

- ^ a b c d e f g h These proportions are fractions of stars brighter than absolute magnitude 16; lowering this limit will render earlier types even rarer, whereas generally adding only to the M class. The proportions are calculated ignoring the value of 800 in the total column since the actual numbers add up to 824.

- ^ Technically, white dwarfs are no longer "live" stars but, rather, the "dead" remains of extinguished stars. Their classification uses a different set of spectral types from element-burning "live" stars.

- ^ When used with A-type stars, this instead refers to abnormally strong metallic spectral lines

- ^ This rises to 78.6% if we include all stars. (See the above note.)

References

[edit]- ^ "Morgan-Keenan Luminosity Class | COSMOS". astronomy.swin.edu.au. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ O'Connell (27 March 2023). "MAGNITUDE AND COLOR SYSTEMS" (PDF). Caltech ASTR 511. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Jeffery, C. S.; Werner, K.; Kilkenny, D.; Miszalski, B.; Monageng, I.; Snowdon, E. J. (2023). "Hot white dwarfs and pre-white dwarfs discovered with SALT". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 519 (2): 2321–2330. arXiv:2301.03550. doi:10.1093/mnras/stac3531.

- ^ a b c d Habets, G. M. H. J.; Heinze, J. R. W. (November 1981). "Empirical bolometric corrections for the main-sequence". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. 46: 193–237 (Tables VII and VIII). Bibcode:1981A&AS...46..193H. – Luminosities are derived from Mbol figures, using Mbol(☉)=4.75.

- ^ Weidner, Carsten; Vink, Jorick S. (December 2010). "The masses, and the mass discrepancy of O-type stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 524. A98. arXiv:1010.2204. Bibcode:2010A&A...524A..98W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014491. S2CID 118836634.

- ^ a b Charity, Mitchell. "What color are the stars?". Vendian.org. Retrieved 13 May 2006.

- ^ "The Colour of Stars". Australia Telescope National Facility. 17 October 2018.

- ^ Moore, Patrick (1992). The Guinness Book of Astronomy: Facts & Feats (4th ed.). Guinness. ISBN 978-0-85112-940-2.

- ^ "The Colour of Stars". Australia Telescope Outreach and Education. 21 December 2004. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2007. — Explains the reason for the difference in color perception.

- ^ a b c d Baraffe, I.; Chabrier, G.; Barman, T. S.; Allard, F.; Hauschildt, P. H. (May 2003). "Evolutionary models for cool brown dwarfs and extrasolar giant planets. The case of HD 209458". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 402 (2): 701–712. arXiv:astro-ph/0302293. Bibcode:2003A&A...402..701B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030252. S2CID 15838318.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ledrew, Glenn (February 2001). "The Real Starry Sky". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 95: 32. Bibcode:2001JRASC..95...32L.

- ^ "Spectral classification of stars (OBAFGKM)". www.eudesign.com. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ "Mnemonics for the Harvard Spectral Classification Scheme". Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ^ "AST 101: The Great Mnemonic Contest". Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ^ Sota, A.; Maíz Apellániz, J.; Morrell, N. I.; Barbá, R. H.; Walborn, N. R.; et al. (March 2014). "The Galactic O-Star Spectroscopic Survey (GOSSS). II. Bright Southern Stars". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 211 (1). 10. arXiv:1312.6222. Bibcode:2014ApJS..211...10S. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/211/1/10. S2CID 118847528.

- ^ a b Phillips, Kenneth J. H. (1995). Guide to the Sun. Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–53. ISBN 978-0-521-39788-9.

- ^ Russell, Henry Norris (March 1914). "Relations Between the Spectra and Other Characteristics of the Stars". Popular Astronomy. Vol. 22. pp. 275–294. Bibcode:1914PA.....22..275R.

- ^ Saha, M. N. (May 1921). "On a Physical Theory of Stellar Spectra". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. 99 (697): 135–153. Bibcode:1921RSPSA..99..135S. doi:10.1098/rspa.1921.0029.

- ^ Payne, Cecilia Helena (1925). Stellar Atmospheres; a Contribution to the Observational Study of High Temperature in the Reversing Layers of Stars (Ph.D). Radcliffe College. Bibcode:1925PhDT.........1P.

- ^ Universe, Physics And (14 June 2013). "The Yerkes spectral classification". Physics and Universe. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ UCL (30 November 2018). "The MKK and Revised MK Atlas". UCL Observatory (UCLO). Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ Morgan, William Wilson; Keenan, Philip Childs; Kellman, Edith (1943). An atlas of stellar spectra, with an outline of spectral classification. The University of Chicago Press. Bibcode:1943assw.book.....M. OCLC 1806249.

- ^ Morgan, William Wilson; Keenan, Philip Childs (1973). "Spectral Classification". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 11: 29–50. Bibcode:1973ARA&A..11...29M. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.11.090173.000333.

- ^ a b c d "A note on the spectral atlas and spectral classification". Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Caballero-Nieves, S. M.; Nelan, E. P.; Gies, D. R.; Wallace, D. J.; DeGioia-Eastwood, K.; et al. (February 2014). "A High Angular Resolution Survey of Massive Stars in Cygnus OB2: Results from the Hubble Space Telescope Fine Guidance Sensors". The Astronomical Journal. 147 (2). 40. arXiv:1311.5087. Bibcode:2014AJ....147...40C. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/147/2/40. S2CID 22036552.

- ^ Prinja, R. K.; Massa, D. L. (October 2010). "Signature of wide-spread clumping in B supergiant winds". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 521. L55. arXiv:1007.2744. Bibcode:2010A&A...521L..55P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015252. S2CID 59151633.

- ^ Gray, David F. (November 2010). "Photospheric Variations of the Supergiant γ Cyg". The Astronomical Journal. 140 (5): 1329–1336. Bibcode:2010AJ....140.1329G. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/140/5/1329.

- ^ a b Nazé, Y. (November 2009). "Hot stars observed by XMM-Newton. I. The catalog and the properties of OB stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 506 (2): 1055–1064. arXiv:0908.1461. Bibcode:2009A&A...506.1055N. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912659. S2CID 17317459.

- ^ Lyubimkov, Leonid S.; Lambert, David L.; Rostopchin, Sergey I.; Rachkovskaya, Tamara M.; Poklad, Dmitry B. (February 2010). "Accurate fundamental parameters for A-, F- and G-type Supergiants in the solar neighbourhood". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 402 (2): 1369–1379. arXiv:0911.1335. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.402.1369L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15979.x. S2CID 119096173.

- ^ Gray, R. O.; Corbally, C. J.; Garrison, R. F.; McFadden, M. T.; Robinson, P. E. (October 2003). "Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: Spectroscopy of Stars Earlier than M0 within 40 Parsecs: The Northern Sample. I". The Astronomical Journal. 126 (4): 2048–2059. arXiv:astro-ph/0308182. Bibcode:2003AJ....126.2048G. doi:10.1086/378365. S2CID 119417105.

- ^ Cenarro, A. J.; Peletier, R. F.; Sanchez-Blazquez, P.; Selam, S. O.; Toloba, E.; Cardiel, N.; Falcon-Barroso, J.; Gorgas, J.; Jimenez-Vicente, J.; Vazdekis, A. (January 2007). "Medium-resolution Isaac Newton Telescope library of empirical spectra - II. The stellar atmospheric parameters". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 374 (2): 664–690. arXiv:astro-ph/0611618. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.374..664C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11196.x. S2CID 119428437.

- ^ Sion, Edward M.; Holberg, J. B.; Oswalt, Terry D.; McCook, George P.; Wasatonic, Richard (December 2009). "The White Dwarfs Within 20 Parsecs of the Sun: Kinematics and Statistics". The Astronomical Journal. 138 (6): 1681–1689. arXiv:0910.1288. Bibcode:2009AJ....138.1681S. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/138/6/1681. S2CID 119284418.

- ^ D.S. Hayes; L.E. Pasinetti; A.G. Davis Philip (6 December 2012). Calibration of Fundamental Stellar Quantities: Proceedings of the 111th Symposium of the International Astronomical Union held at Villa Olmo, Como, Italy, May 24–29, 1984. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-94-009-5456-4.

- ^ a b Arias, Julia I.; et al. (August 2016). "Spectral Classification and Properties of the OVz Stars in the Galactic O Star Spectroscopic Survey (GOSSS)". The Astronomical Journal. 152 (2): 31. arXiv:1604.03842. Bibcode:2016AJ....152...31A. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/2/31. S2CID 119259952.

- ^ MacRobert, Alan (1 August 2006). "The Spectral Types of Stars". Sky & Telescope.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Allen, J. S. "The Classification of Stellar Spectra". UCL Department of Physics and Astronomy: Astrophysics Group. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ a b Maíz Apellániz, J.; Walborn, Nolan R.; Morrell, N. I.; Niemela, V. S.; Nelan, E. P. (2007). "Pismis 24-1: The Stellar Upper Mass Limit Preserved". The Astrophysical Journal. 660 (2): 1480–1485. arXiv:astro-ph/0612012. Bibcode:2007ApJ...660.1480M. doi:10.1086/513098. S2CID 15936535.

- ^ Walborn, Nolan R.; Sota, Alfredo; Maíz Apellániz, Jesús; Alfaro, Emilio J.; Morrell, Nidia I.; Barbá, Rodolfo H.; Arias, Julia I.; Gamen, Roberto C. (2010). "Early Results from the Galactic O-Star Spectroscopic Survey: C III Emission Lines in of Spectra". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 711 (2): L143. arXiv:1002.3293. Bibcode:2010ApJ...711L.143W. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/711/2/L143. S2CID 119122481.

- ^ a b Fariña, Cecilia; Bosch, Guillermo L.; Morrell, Nidia I.; Barbá, Rodolfo H.; Walborn, Nolan R. (2009). "Spectroscopic Study of the N159/N160 Complex in the Large Magellanic Cloud". The Astronomical Journal. 138 (2): 510–516. arXiv:0907.1033. Bibcode:2009AJ....138..510F. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/138/2/510. S2CID 18844754.

- ^ Rauw, G.; Manfroid, J.; Gosset, E.; Nazé, Y.; Sana, H.; De Becker, M.; Foellmi, C.; Moffat, A. F. J. (2007). "Early-type stars in the core of the young open cluster Westerlund 2". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 463 (3): 981–991. arXiv:astro-ph/0612622. Bibcode:2007A&A...463..981R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066495. S2CID 17776145.

- ^ a b c d e f g Crowther, Paul A. (2007). "Physical Properties of Wolf-Rayet Stars". Annual Review of Astronomy & Astrophysics. 45 (1): 177–219. arXiv:astro-ph/0610356. Bibcode:2007ARA&A..45..177C. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.45.051806.110615. S2CID 1076292.

- ^ Rountree Lesh, J. (1968). "The Kinematics of the Gould Belt: An Expanding Group?". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 17: 371. Bibcode:1968ApJS...17..371L. doi:10.1086/190179.

- ^ Analyse spectrale de la lumière de quelques étoiles, et nouvelles observations sur les taches solaires, P. Secchi, Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences 63 (July–December 1866), pp. 364–368.

- ^ Nouvelles recherches sur l'analyse spectrale de la lumière des étoiles, P. Secchi, Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences 63 (July–December 1866), pp. 621–628.

- ^ Hearnshaw, J. B. (1986). The Analysis of Starlight: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Astronomical Spectroscopy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 60, 134. ISBN 978-0-521-25548-6.

- ^ "Classification of Stellar Spectra: Some History".

- ^ Kaler, James B. (1997). Stars and Their Spectra: An Introduction to the Spectral Sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-521-58570-5.

- ^ p. 60–63, Hearnshaw 1986; pp. 623–625, Secchi 1866.

- ^ pp. 62–63, Hearnshaw 1986.

- ^ p. 60, Hearnshaw 1986.

- ^ Catchers of the Light: The Forgotten Lives of the Men and Women Who First Photographed the Heavens by Stefan Hughes.

- ^ a b Pickering, Edward C. (1890). "The Draper Catalogue of stellar spectra photographed with the 8-inch Bache telescope as a part of the Henry Draper memorial". Annals of Harvard College Observatory. 27: 1. Bibcode:1890AnHar..27....1P.

- ^ a b pp. 106–108, Hearnshaw 1986.

- ^ Payne, Cecilia H. (1930). "Classification of the O Stars". Harvard College Observatory Bulletin. 878: 1. Bibcode:1930BHarO.878....1P.

- ^ a b "Williamina Fleming". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ "Williamina Paton Fleming -". www.projectcontinua.org. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ "Classification of stellar spectra". spiff.rit.edu. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Hearnshaw (1986) pp. 111–112

- ^ Maury, Antonia C.; Pickering, Edward C. (1897). "Spectra of bright stars photographed with the 11 inch Draper Telescope as part of the Henry Draper Memorial". Annals of Harvard College Observatory. 28: 1. Bibcode:1897AnHar..28....1M.

- ^ a b "Antonia Maury". www.projectcontinua.org. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

Hearnshaw, J.B. (17 March 2014). The analysis of starlight: Two centuries of astronomical spectroscopy (2nd ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-107-03174-6. OCLC 855909920.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Gray, Richard O.; Corbally, Christopher J.; Burgasser, Adam J. (2009). Stellar spectral classification. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12510-7. OCLC 276340686. - ^ Jones, Bessie Zaban; Boyd, Lyle Gifford (1971). The Harvard College Observatory: The first four directorships, 1839-1919 (1st ed.). Cambridge: M.A. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-41880-6. OCLC 1013948519.

- ^ Cannon, Annie J.; Pickering, Edward C. (1901). "Spectra of bright southern stars photographed with the 13 inch Boyden telescope as part of the Henry Draper Memorial". Annals of Harvard College Observatory. 28: 129. Bibcode:1901AnHar..28..129C.

- ^ Hearnshaw (1986) pp. 117–119,

- ^ Cannon, Annie Jump; Pickering, Edward Charles (1912). "Classification of 1,688 southern stars by means of their spectra". Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College. 56 (5): 115. Bibcode:1912AnHar..56..115C.

- ^ Hearnshaw (1986) pp. 121–122

- ^ "Annie Jump Cannon". www.projectcontinua.org. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Nassau, J. J.; Seyfert, Carl K. (March 1946). "Spectra of BD Stars Within Five Degrees of the North Pole". Astrophysical Journal. 103: 117. Bibcode:1946ApJ...103..117N. doi:10.1086/144796.

- ^ FitzGerald, M. Pim (October 1969). "Comparison Between Spectral-Luminosity Classes on the Mount Wilson and Morgan–Keenan Systems of Classification". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 63: 251. Bibcode:1969JRASC..63..251P.

- ^ Sandage, A. (December 1969). "New subdwarfs. II. Radial velocities, photometry, and preliminary space motions for 112 stars with large proper motion". Astrophysical Journal. 158: 1115. Bibcode:1969ApJ...158.1115S. doi:10.1086/150271.

- ^ Norris, Jackson M.; Wright, Jason T.; Wade, Richard A.; Mahadevan, Suvrath; Gettel, Sara (December 2011). "Non-detection of the Putative Substellar Companion to HD 149382". The Astrophysical Journal. 743 (1). 88. arXiv:1110.1384. Bibcode:2011ApJ...743...88N. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/743/1/88. S2CID 118337277.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Garrison, R. F. (1994). "A Hierarchy of Standards for the MK Process" (PDF). In Corbally, C. J.; Gray, R. O.; Garrison, R. F. (eds.). The MK Process at 50 Years: A Powerful Tool for Astrophysical Insight. Astronomical Society of the Pacific conference series. Vol. 60. San Francisco: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 3–14. ISBN 978-1-58381-396-6. OCLC 680222523.

- ^ Darling, David. "late-type star". The Internet Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Walborn, N. R. (2008). "Multiwavelength Systematics of OB Spectra". Massive Stars: Fundamental Parameters and Circumstellar Interactions (Eds. P. Benaglia. 33: 5. Bibcode:2008RMxAC..33....5W.

- ^ An atlas of stellar spectra, with an outline of spectral classification, W. W. Morgan, P. C. Keenan and E. Kellman, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1943.

- ^ Walborn, N. R. (1971). "Some Spectroscopic Characteristics of the OB Stars: An Investigation of the Space Distribution of Certain OB Stars and the Reference Frame of the Classification". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 23: 257. Bibcode:1971ApJS...23..257W. doi:10.1086/190239.

- ^ Morgan, W. W.; Abt, Helmut A.; Tapscott, J. W. (1978). "Revised MK Spectral Atlas for stars earlier than the sun". Williams Bay: Yerkes Observatory. Bibcode:1978rmsa.book.....M.

- ^ Walborn, Nolan R.; Howarth, Ian D.; Lennon, Daniel J.; Massey, Philip; Oey, M. S.; Moffat, Anthony F. J.; Skalkowski, Gwen; Morrell, Nidia I.; Drissen, Laurent; Parker, Joel Wm. (2002). "A New Spectral Classification System for the Earliest O Stars: Definition of Type O2" (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 123 (5): 2754–2771. Bibcode:2002AJ....123.2754W. doi:10.1086/339831. S2CID 122127697.

- ^ Elizabeth Howell (21 September 2013). "Regulus: The Kingly Star". Space.com. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ Slettebak, Arne (July 1988). "The Be Stars". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 100: 770–784. Bibcode:1988PASP..100..770S. doi:10.1086/132234.

- ^ "THE 100 NEAREST STAR SYSTEMS". www.astro.gsu.edu. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ "Stars within 20 light-years".

- ^ Morgan, W. W.; Keenan, P. C. (1973). "Spectral Classification". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 11: 29. Bibcode:1973ARA&A..11...29M. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.11.090173.000333.

- ^ Morgan, W. W.; Abt, Helmut A.; Tapscott, J. W. (1978). Revised MK Spectral Atlas for stars earlier than the sun. Yerkes Observatory, University of Chicago. Bibcode:1978rmsa.book.....M.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gray, R. O; Garrison, R. F (1989). "The early F-type stars - Refined classification, confrontation with Stromgren photometry, and the effects of rotation". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 69: 301. Bibcode:1989ApJS...69..301G. doi:10.1086/191315.

- ^ Keenan, Philip C.; McNeil, Raymond C. (1989). "The Perkins catalog of revised MK types for the cooler stars". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 71: 245. Bibcode:1989ApJS...71..245K. doi:10.1086/191373. S2CID 123149047.

- ^ Nieuwenhuijzen, H.; De Jager, C. (2000). "Checking the yellow evolutionary void. Three evolutionary critical Hypergiants: HD 33579, HR 8752 & IRC +10420". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 353: 163. Bibcode:2000A&A...353..163N.

- ^ "On a cosmological timescale, The Earth's period of habitability is nearly over | International Space Fellowship". Spacefellowship.com. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ ""Goldilocks" Stars May Be "Just Right" for Finding Habitable Worlds". NASA.com. 7 March 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Discovered: Stars as Cool as the Human Body | Science Mission Directorate". science.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ "Galactic refurbishment". www.spacetelescope.org. ESA/Hubble. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Payne, Cecilia H. (1930). "Classification of the O Stars". Harvard College Observatory Bulletin. 878: 1. Bibcode:1930BHarO.878....1P.

- ^ Figer, Donald F.; McLean, Ian S.; Najarro, Francisco (1997). "AK-Band Spectral Atlas of Wolf-Rayet Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 486 (1): 420–434. Bibcode:1997ApJ...486..420F. doi:10.1086/304488.

- ^ Kingsburgh, R. L.; Barlow, M. J.; Storey, P. J. (1995). "Properties of the WO Wolf-Rayet stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 295: 75. Bibcode:1995A&A...295...75K.

- ^ Tinkler, C. M.; Lamers, H. J. G. L. M. (2002). "Mass-loss rates of H-rich central stars of planetary nebulae as distance indicators?". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 384 (3): 987–998. Bibcode:2002A&A...384..987T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020061.

- ^ Miszalski, B.; Crowther, P. A.; De Marco, O.; Köppen, J.; Moffat, A. F. J.; Acker, A.; Hillwig, T. C. (2012). "IC 4663: The first unambiguous [WN] Wolf-Rayet central star of a planetary nebula". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 423 (1): 934–947. arXiv:1203.3303. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.423..934M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.20929.x. S2CID 10264296.

- ^ Crowther, P. A.; Walborn, N. R. (2011). "Spectral classification of O2-3.5 If*/WN5-7 stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 416 (2): 1311–1323. arXiv:1105.4757. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.416.1311C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19129.x. S2CID 118455138.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2008). "Outstanding Issues in Our Understanding of L, T, and Y Dwarfs". 14th Cambridge Workshop on Cool Stars. 384: 85. arXiv:0704.1522. Bibcode:2008ASPC..384...85K.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Reid, I. Neill; Liebert, James; Cutri, Roc M.; Nelson, Brant; Beichman, Charles A.; Dahn, Conard C.; Monet, David G.; Gizis, John E.; Skrutskie, Michael F. (10 July 1999). "Dwarfs Cooler than M: the Definition of Spectral Type L Using Discovery from the 2-µ ALL-SKY Survey (2MASS)". The Astrophysical Journal. 519 (2): 802–833. Bibcode:1999ApJ...519..802K. doi:10.1086/307414.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, J. Davy (2005). "New Spectral Types L and T" (PDF). Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 43 (1): 195–246. Bibcode:2005ARA&A..43..195K. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.42.053102.134017. S2CID 122318616.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Barman, Travis S.; Burgasser, Adam J.; McGovern, Mark R.; McLean, Ian S.; Tinney, Christopher G.; Lowrance, Patrick J. (2006). "Discovery of a Very Young Field L Dwarf, 2MASS J01415823−4633574". The Astrophysical Journal. 639 (2): 1120–1128. arXiv:astro-ph/0511462. Bibcode:2006ApJ...639.1120K. doi:10.1086/499622. S2CID 13075577.

- ^ Camenzind, Max (27 September 2006). "Classification of Stellar Spectra and its Physical Interpretation" (PDF). Astro Lab Landessternwarte Königstuhl: 6 – via Heidelberg University.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Cushing, Michael C.; Gelino, Christopher R.; Beichman, Charles A.; Tinney, C. G.; Faherty, Jacqueline K.; Schneider, Adam; Mace, Gregory N. (2013). "Discovery of the Y1 Dwarf WISE J064723.23-623235.5". The Astrophysical Journal. 776 (2): 128. arXiv:1308.5372. Bibcode:2013ApJ...776..128K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/776/2/128. S2CID 6230841.

- ^ Deacon, N. R.; Hambly, N. C. (2006). "Y-Spectral class for Ultra-Cool Dwarfs". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 371: 1722–1730. arXiv:astro-ph/0607305. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10795.x. S2CID 14081778.

- ^ a b Wehner, Mike (24 August 2011). "NASA spots chilled-out stars cooler than the human body | Technology News Blog – Yahoo! News Canada". Ca.news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ a b Venton, Danielle (23 August 2011). "NASA Satellite Finds Coldest, Darkest Stars Yet". Wired – via www.wired.com.

- ^ "NASA - NASA'S Wise Mission Discovers Coolest Class of Stars". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ Zuckerman, B.; Song, I. (2009). "The minimum Jeans mass, brown dwarf companion IMF, and predictions for detection of Y-type dwarfs". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 493 (3): 1149–1154. arXiv:0811.0429. Bibcode:2009A&A...493.1149Z. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810038. S2CID 18147550.

- ^ a b c Dupuy, T. J.; Kraus, A. L. (2013). "Distances, Luminosities, and Temperatures of the Coldest Known Substellar Objects". Science. 341 (6153): 1492–5. arXiv:1309.1422. Bibcode:2013Sci...341.1492D. doi:10.1126/science.1241917. PMID 24009359. S2CID 30379513.

- ^ a b c Leggett, Sandy K.; Cushing, Michael C.; Saumon, Didier; Marley, Mark S.; Roellig, Thomas L.; Warren, Stephen J.; Burningham, Ben; Jones, Hugh R. A.; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Lodieu, Nicolas; Lucas, Philip W.; Mainzer, Amy K.; Martín, Eduardo L.; McCaughrean, Mark J.; Pinfield, David J.; Sloan, Gregory C.; Smart, Richard L.; Tamura, Motohide; Van Cleve, Jeffrey E. (2009). "The Physical Properties of Four ~600 K T Dwarfs". The Astrophysical Journal. 695 (2): 1517–1526. arXiv:0901.4093. Bibcode:2009ApJ...695.1517L. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/695/2/1517. S2CID 44050900.

- ^ Delorme, Philippe; Delfosse, Xavier; Albert, Loïc; Artigau, Étienne; Forveille, Thierry; Reylé, Céline; Allard, France; Homeier, Derek; Robin, Annie C.; Willott, Chris J.; Liu, Michael C.; Dupuy, Trent J. (2008). "CFBDS J005910.90-011401.3: Reaching the T-Y brown dwarf transition?". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 482 (3): 961–971. arXiv:0802.4387. Bibcode:2008A&A...482..961D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20079317. S2CID 847552.

- ^ Burningham, Ben; Pinfield, D. J.; Leggett, S. K.; Tamura, M.; Lucas, P. W.; Homeier, D.; Day-Jones, A.; Jones, H. R. A.; Clarke, J. R. A.; Ishii, M.; Kuzuhara, M.; Lodieu, N.; Zapatero-Osorio, María Rosa; Venemans, B. P.; Mortlock, D. J.; Barrado y Navascués, D.; Martin, Eduardo L.; Magazzù, Antonio (2008). "Exploring the substellar temperature regime down to ~550 K". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 391 (1): 320–333. arXiv:0806.0067. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.391..320B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13885.x. S2CID 1438322.

- ^ European Southern Observatory. "A Very Cool Pair of Brown Dwarfs", 23 March 2011

- ^ Luhman, Kevin L.; Esplin, Taran L. (May 2016). "The Spectral Energy Distribution of the Coldest Known Brown Dwarf". The Astronomical Journal. 152 (3): 78. arXiv:1605.06655. Bibcode:2016AJ....152...78L. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/3/78. S2CID 118577918.

- ^ "Spectral type codes". simbad.u-strasbg.fr. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ a b Burningham, Ben; Smith, L.; Cardoso, C.V.; Lucas, P.W.; Burgasser, Adam J.; Jones, H.R.A.; Smart, R.L. (May 2014). "The discovery of a T6.5 subdwarf". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 440 (1): 359–364. arXiv:1401.5982. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.440..359B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu184. ISSN 0035-8711. S2CID 119283917.

- ^ a b c Cruz, Kelle L.; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Burgasser, Adam J. (February 2009). "Young L dwarfs identified in the field: A preliminary low-gravity, optical spectral Sequence from L0 to L5". The Astronomical Journal. 137 (2): 3345–3357. arXiv:0812.0364. Bibcode:2009AJ....137.3345C. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/2/3345. ISSN 0004-6256. S2CID 15376964.

- ^ a b Looper, Dagny L.; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Cutri, Roc M.; Barman, Travis; Burgasser, Adam J.; Cushing, Michael C.; Roellig, Thomas; McGovern, Mark R.; McLean, Ian S.; Rice, Emily; Swift, Brandon J. (October 2008). "Discovery of two nearby peculiar L dwarfs from the 2MASS Proper-Motion Survey: Young or metal-rich?". Astrophysical Journal. 686 (1): 528–541. arXiv:0806.1059. Bibcode:2008ApJ...686..528L. doi:10.1086/591025. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 18381182.

- ^ a b c d Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Looper, Dagny L.; Burgasser, Adam J.; Schurr, Steven D.; Cutri, Roc M.; Cushing, Michael C.; Cruz, Kelle L.; Sweet, Anne C.; Knapp, Gillian R.; Barman, Travis S.; Bochanski, John J. (September 2010). "Discoveries from a near-infrared proper motion survey using multi-epoch Two Micron All-Sky Survey data". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 190 (1): 100–146. arXiv:1008.3591. Bibcode:2010ApJS..190..100K. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/190/1/100. ISSN 0067-0049. S2CID 118435904.