Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

New Partnership for Africa's Development

View on Wikipedia

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

This article needs to be updated. (December 2018) |

The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) is an economic development program of the African Union (AU). NEPAD was adopted by the AU at the 37th session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government in July 2001 in Lusaka, Zambia. NEPAD aims to provide an overarching vision and policy framework for accelerating economic co-operation and integration among African countries.

Origins and function

[edit]NEPAD is a merger of two plans for the economic regeneration of Africa: the Millennium Partnership for the African Recovery Programme (MAP), led by Former President Thabo Mbeki of South Africa in conjunction with Former President Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria and President Abdelaziz Bouteflika of Algeria; and the OMEGA Plan for Africa developed by President Abdoulaye Wade of Senegal. At a summit in Sirte, Libya, March 2001, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) agreed that the MAP and OMEGA Plans should be merged.[1]

The UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) developed a "Compact for Africa’s Recovery" based on both these plans and on resolutions on Africa adopted by the United Nations Millennium Summit in September 2000, and submitted a merged document to the Conference of African Ministers of Finance and Ministers of Development and Planning in Algiers, May 2001.[2]

In July 2001, the OAU Assembly of Heads of State and Government meeting in Lusaka, Zambia, adopted this document under the name of the New African Initiative (NAI). The leaders of G8 countries endorsed the plan on July 20, 2001; and other international development partners, including the European Union, China, and Japan also made public statements indicating their support for the program. The Heads of State and Government Implementation Committee (HSGIC) for the project finalized the policy framework and named it the New Partnership for Africa's Development on 23 October 2001. NEPAD became a program of the African Union (AU) after it replaced the OAU in 2002, though it has its own secretariat based in South Africa to coordinate and implement its programmes.

NEPAD's four primary objectives are: to eradicate poverty, promote sustainable growth and development, integrate Africa in the world economy, and accelerate the empowerment of women. It is based on underlying principles of a commitment to good governance, democracy, human rights and conflict resolution; and the recognition that maintenance of these standards is fundamental to the creation of an environment conducive to investment and long-term economic growth. NEPAD seeks to attract increased investment, capital flows and funding, providing an African-owned framework for development as the foundation for partnership at regional and international levels.

In July 2002, the Durban AU summit supplemented NEPAD with a Declaration on Democracy, Political, Economic and Corporate Governance. According to the Declaration, states participating in NEPAD ‘believe in just, honest, transparent, accountable and participatory government and probity in public life’. Accordingly, they ‘undertake to work with renewed determination to enforce’, among other things, the rule of law; the equality of all citizens before the law; individual and collective freedoms; the right to participate in free, credible and democratic political processes; and adherence to the separation of powers, including protection for the independence of the judiciary and the effectiveness of parliaments.

The Declaration on Democracy, Political, Economic and Corporate Governance also committed participating states to establish an African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) to promote adherence to and fulfilment of its commitments. The 2002 Durban summit adopted a document outlining the stages of peer review and the principles by which the APRM should operate; further core documents were adopted at a meeting in Abuja in March 2003, including a Memorandum of Understanding to be signed by governments wishing to undertake the peer review.

Current status

[edit]Successive AU summits and meetings of the HSGIC have proposed the greater integration of NEPAD into the AU's structures and processes. In March 2007 there was a "brainstorming session" on NEPAD held in Algeria at which the future of NEPAD and its relationship with the AU was discussed by an ad hoc committee of heads of state. The committee again recommended the fuller integration of NEPAD with the AU.[3] In April 2008, a review summit of five heads of state—Presidents Mbeki of South Africa, Wade of Senegal, Bouteflika of Algeria, Mubarak of Egypt and Yar'Adua of Nigeria—met in Senegal with a mandate to consider the progress in implementing NEPAD and report to the next AU summit to be held in Egypt in July 2008.[4] In July 2018, the African Union (AU) Assembly approved the transformation of the NEPAD Planning and Coordinating Agency into the African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD), establishing it as the AU's technical body to drive the implementation of Agenda 2063.[5]

Structure

[edit]| Development economics |

|---|

|

| Economies by region |

| Economic growth theories |

| Fields and subfields |

| Lists |

AUDA-NEPAD Heads of State and Government Committee (HSGOC)

[edit]A 33-Member State sub-committee of the African Union Assembly of Heads of State and Government that provides the highest political leadership and strategic guidance on Agenda 2063 priority issues and reports its recommendations to the full Assembly for endorsement. The Chairperson of the AU Commission also participates in HSGOC Summits. The current (2025) Chairperson of the AUDA-NEPAD HSGOC is H.E. Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, President of the Arab Republic of Egypt.

There is also a Steering Committee, comprising 20 AU member states, to oversee the development of policies, programs and projects -this committee reports to the HSGIC.

The NEPAD Secretariat, renamed the NEPAD Planning and Coordinating Agency (NPCA), was later integrated into the African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD) and remains based in Midrand, South Africa. The NEPAD Secretariat is not responsible for the implementation of development programs itself, but works with the African Regional Economic Communities— the building blocks of the African Union.[6] The role of the NEPAD Secretariat is one of coordination and resource mobilisation.

Many individual African states have also established national NEPAD structures responsible for liaison with the continental initiatives on economic reform and development programs.

Chief Executive Officers

[edit]| No. | Image | Name | Country | Took office | Left office |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

Wiseman Nkuhlu | 2000 | 2005[7] | |

| 2 |

|

Firmino Mucavele | 2005 | 2008[8] | |

| 3 |

|

Ibrahim Hassane Mayaki | 2009[9] | 2022[10] | |

| 4 |

|

Nardos Bekele-Thomas | 2022[12] | Incumbent |

Partners

[edit]- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA)

- African Development Bank

- Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA)

- Investment Climate Facility (ICF)

- African Capacity Building Foundation

- Office of the UN Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser on Africa

- IDC (The Industrial Development Corporation) - Sponsor of NEPAD

Programs

[edit]The eight priority areas of NEPAD are: political, economic and corporate governance; agriculture; infrastructure; education; health; science and technology; market access and tourism; and environment.

During the first few years of its existence, the main task of the NEPAD Secretariat and key supporters was the popularisation of NEPAD's key principles, as well as the development of action plans for each of the sectoral priorities. NEPAD also worked to develop partnerships with international development finance institutions—including the World Bank, G8, European Commission, UNECA and others—and with the private sector.[13]

After this initial phase, more concrete programs were developed, including:

- The Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), aimed at assisting the launching of a 'green revolution' in Africa, based on a belief in the key role of agriculture in development. To monitor its progress, the Regional Strategic Analysis and Knowledge Support System was created.[14]

- The Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA), which comprises numerous trans-boundary infrastructure projects in the four sectors transport, energy, water and ICT, aimed at boosting intra-African trade and interconnecting the continent.

- The NEPAD Science and Technology programme, including an emphasis on research in areas such as water science and energy.

- The "e-schools programme", adopted by the HSGIC in 2003 as an initiative with the original goal of equipping all 600,000 primary and secondary schools in Africa with IT equipment and internet access by 2013, in partnership with several large IT companies. See NEPAD E-School program

- The launch of a Pan African Infrastructure Development Fund (PAIDF) by the Public Investment Corporation of South Africa, to finance high priority cross-border infrastructure projects.

- Capacity building for continental institutions, working with the African Capacity Building Foundation, the Southern Africa Trust, UNECA, the African Development Bank, and other development partners. One of NEPAD's priorities has been to strengthen the capacity of and linkages among the Regional Economic Communities.

- NEPAD was involved with the Timbuktu Manuscripts Project although it is not entirely clear to what extent.

Criticism

[edit]NEPAD was initially met with a great deal of scepticism from much of civil society in Africa as playing into the 'Washington Consensus' model of economic development. In July 2002, members of some 40 African social movements, trade unions, youth and women's organizations, NGOs, religious organizations and others endorsed the African Civil Society Declaration on NEPAD[15] rejecting NEPAD; a similar hostile view was taken by African scholars and activist intellectuals in the 2002 Accra Declaration on Africa's Development Challenges.[16]

Part of the problem in this rejection was that the process by which NEPAD was adopted was insufficiently participatory—civil society was almost totally excluded from the discussions by which it came to be adopted.[citation needed]

More recently, NEPAD has also been criticised by some of its initial backers, including notably Senegalese President Abdoulaye Wade, who accused NEPAD of wasting hundreds of millions of dollars and achieving nothing.[17] Like many other intergovernmental bodies, NEPAD suffers from slow decision-making,[18] and a relatively poorly resourced and often cumbersome implementing framework. The great lack of information about the day-to-day activities of the NEPAD secretariat—the website is notably uninformative—does not help its case.[19]

However, the program has also received some acceptance from those who were initially very critical, and, in general, has seen its status become less controversial as it becomes more established and its programs become more concrete. The aim of promoting greater regional integration and trade among African states is welcomed by many, even as the fundamental macroeconomic principles NEPAD endorses remain contested.[20]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- The New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD): An Initial Commentary by Ravi Kanbur, Cornell University

- Nepad’s APRM: A Progress Report, Practical Limitations and Challenges, by Ayesha Kajee

- "Fanon's Warning: A Civil Society Reader on the New Partnership for Africa's Development", edited by Patrick Bond, Africa World Press, 2002

- "The New Partnership for Africa's Development: Challenges and Developments", Centre for Democracy and Development (Nigeria), 2003

- "NEPAD: A New Path?" edited by Peter Anyang' Nyong'o, Aseghedech Ghirmazion and Davinder Lamba, Heinrich Boell Foundation, 2002

- "The African Union, NEPAD, and Human Rights: The Missing Agenda" by Bronwen Manby, Human Rights Quarterly - Volume 26, Number 4, November 2004, pp. 983–1027

- "Economic Policy and Conflict in Africa" in Journal of Peacebuilding and Development, Vol.2, No.1, 2004; pp. 6–20

- "Pan-Africa: The NEPAD formula" by Sarah Coleman, World Press Review July 2002 v49 i7 p29(1)

- "Bring Africa out of the margins", The Christian Science Monitor July 5, 2002 p10

References

[edit]- ^ [1] Archived 26 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [2] Archived 26 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Conclusions and Recommendations of the NEPAD Heads of State and Government Implementation Committee (HSGIC) Meeting and Brainstorming on NEPAD, Algiers, Algeria, NEPAD Secretariat, 21 March 2007.

- ^ Bathandwa Mbola, "NEPAD summit to discuss global challenges facing Africa" Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, BuaNews (SA govt), 15 April 2008

- ^ "About AUDA-NEPAD | AUDA-NEPAD". www.nepad.org. Retrieved 6 June 2025.

- ^ The Regional Economic Communities recognised by the AU are: The Economic Commission of West African States (ECOWAS), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the East African Community (EAC), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the Intergovernmental Authority for Development (IGAD -- operational in the horn of Africa), and the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU).

- ^ "NEPAD Initiators speak at 10th Anniversary Colloquium. | AUDA-NEPAD". nepad.org. 28 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ "Communiqué - Prof. Firmino G. MUCAVELE | AUDA-NEPAD". nepad.org. 20 May 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ "E Ebrahim receives credentials from Nepad Secretariat CEO". Info.gov.za. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ^ "New CEO of African Union Development Agency-NEPAD assumes office on 1 May". Africa Renewal. United Nations. 10 May 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ Wakhisi, Sylvia (11 July 2015). "High flyer: Meet UNDP Resident Representative Nardos Bekele-Thomas". Eve. The Standard (Kenya). Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ "H.E. Madam Nardos Bekele-Thomas | Global Africa Business Initiative". gabi.unglobalcompact.org. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ For a discussion of NEPAD's challenges and achievements, see NEPAD: a look at seven years of achievement – and the challenges on the way forward[permanent dead link], an address by Prof. Wiseman Nkuhlu, a former Chief Executive of NEPAD, delivered at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, published in NEPAD Dialogue (NEPAD Secretariat), 25 January 2008.

- ^ "About | ReSAKSS". www.resakss.org. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ African Civil Society Declaration on NEPAD Archived 14 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine African Civil Society Declaration on NEPAD.

- ^ Accra Declaration Archived 30 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine Declaration on Africa's Development Challenges. Adopted at end of Joint CODESRIA-TWN-AFRICA Conference on Africa's Development Challenges in the Millennium, Accra 23–26 April 2002.

- ^ Senegal president slams Nepad IOL June 14, 2007.

- ^ Dundas, Carl W. (8 November 2011). The Lag of 21St Century Democratic Elections: in the African Union Member States. Author House. ISBN 978-1-4567-9707-2.

- ^ "NEPAD ACRONYMS". SlideShare. 26 July 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ Edo, Victor Osaro; Olanrewaju, Michael Abiodun (2012). "An Assessmnent of the Transformation of the Organization of African Unity (O.a.u) to the African Union (A.u), 19632007". Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria. 21: 41–69. ISSN 0018-2540. JSTOR 41857189.

External links

[edit]New Partnership for Africa's Development

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Formation and Initial Launch (2001)

The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) emerged from the convergence of continent-wide efforts to establish an African-owned framework for economic renewal and integration, building on prior national and regional proposals. In 2000, South African President Thabo Mbeki, Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, and Senegalese President Abdoulaye Wade collaborated to merge initiatives such as Senegal's Omega Plan—focused on infrastructure and agriculture—and the New Africa Initiative, which emphasized political governance and economic cooperation among larger African economies.[3][11] This synthesis addressed Africa's structural challenges, including dependency on external aid and weak intra-continental trade, by prioritizing self-reliance and peer-reviewed governance commitments.[12] At the 37th Ordinary Session of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) Assembly of Heads of State and Government, held in Lusaka, Zambia, from July 9–11, 2001, the assembled leaders endorsed the New Africa Initiative as a unified strategic framework, later rebranded NEPAD to underscore its partnership ethos with global actors while maintaining African agency.[13][14] The Lusaka Declaration formalized NEPAD's core pillars—political stability, economic integration, and sustainable development—aiming to eradicate poverty through accelerated growth rates exceeding 7% annually via investments in infrastructure, agriculture, and human capital.[15] This adoption marked a shift from donor-driven paradigms, introducing mechanisms like the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) for voluntary governance assessments among participating states.[12] NEPAD's policy framework was finalized and officially launched on October 23, 2001, during a ministerial meeting in Abuja, Nigeria, establishing the Heads of State and Government Implementation Committee (HSIC) chaired initially by Obasanjo, with Mbeki as vice-chair, to oversee execution.[16][17] The launch emphasized attracting foreign direct investment through improved policy environments, targeting sectors like energy and transport to foster regional economic corridors, while committing to anti-corruption and democratic consolidation as preconditions for external partnerships.[15] Early endorsements from the G8 and international financial institutions highlighted NEPAD's potential, though implementation hinged on domestic political will amid diverse national capacities across Africa's 54 states.[12]Adoption and Early Institutionalization (2002–2010)

Following its initial endorsement by the Organisation of African Unity in July 2001, NEPAD was formally ratified by the African Union at its inaugural Assembly in Durban, South Africa, on 9 July 2002, establishing it as the principal socioeconomic development framework for the continent.[2] This adoption occurred concurrently with the AU's formation, supplanting the OAU, and positioned NEPAD to coordinate priority programs across African states while emphasizing self-reliance and good governance.[2] Institutional structures were rapidly formalized to support implementation. The Heads of State and Government Implementation Committee (HSGIC), initially formed in 2001 with 20 members—including the five originating countries (Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria, Senegal, and South Africa) plus 15 elected states—continued to provide strategic oversight, reporting annually to AU summits.[2] A Steering Committee, composed of personal representatives from HSGIC members, handled operational coordination. The NEPAD Secretariat, headquartered in Midrand, South Africa, was established to manage day-to-day activities, facilitating program execution and partnerships.[18] Key early initiatives underscored institutionalization efforts. In March 2003, the HSGIC launched the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) in Abuja, Nigeria, as a voluntary tool to assess governance standards and foster political stability, with initial countries like Rwanda acceding shortly thereafter.[19] By July 2003, the AU Assembly mandated progressive integration of NEPAD into its structures, directing the AU Commission and NEPAD Secretariat to harmonize agendas. This period also saw the development of sector-specific programs, such as infrastructure consortia, though implementation faced challenges including limited funding and uneven political commitment across member states.[20] From 2005 onward, leadership transitions and expanded partnerships advanced operational capacity. The Secretariat coordinated engagements with G8 nations, culminating in the 2002 G8 Africa Action Plan endorsing NEPAD priorities.[21] By 2009, amid pushes for deeper AU alignment, Ibrahim Assane Mayaki was appointed CEO, setting the stage for the 2010 transformation of the Secretariat into the NEPAD Planning and Coordinating Agency as an autonomous AU technical body.[2] These developments solidified NEPAD's role, despite critiques of its top-down approach and reliance on external aid.[22]Evolution into AUDA-NEPAD (2010–2018)

In February 2010, the 14th Ordinary Session of the African Union Assembly in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, adopted Decision Assembly/AU/Dec.283(XIV), approving the full integration of NEPAD into the AU's structures and processes.[2] This decision transformed the NEPAD Secretariat, previously an autonomous body, into the NEPAD Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency), headquartered in Midrand, South Africa, to serve as the technical arm for coordinating continental development initiatives.[18] The Agency's establishment allocated an initial budget of US$3,020,854 from the AU to support the transition and operations.[23] From 2010 to 2018, the NEPAD Agency operated under the oversight of the AU Assembly, the NEPAD Heads of State and Government Orientation Committee (HSGOC), and a Steering Committee comprising representatives from 20 AU member states, including the five initiating countries (Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria, Senegal, and South Africa) and 15 elected from regional economic communities.[24] Its mandate emphasized facilitating the implementation of priority programs in areas such as infrastructure, agriculture, and regional integration, while mobilizing resources and fostering partnerships with entities like the African Development Bank, United Nations agencies, and regional economic communities.[24] The Agency aligned its efforts with emerging AU frameworks, including preparations for Agenda 2063, by prioritizing high-impact projects and knowledge-sharing mechanisms to address development gaps.[24] Governance included observer status for the African Peer Review Mechanism, regional economic communities, and international partners, ensuring coordinated execution of AU priorities.[24] The period culminated in institutional reforms driven by the need to streamline AU operations and enhance development delivery. In July 2018, at the 31st Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly in Nouakchott, Mauritania, leaders approved Decision Assembly/AU/Dec.691(XXXI), transforming the NEPAD Agency into the African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD) as the AU's dedicated technical executive agency.[25] This evolution, part of broader AU reforms recommended in President Paul Kagame's 2018 report on institutional efficiency, aimed to consolidate NEPAD's role in accelerating Agenda 2063 implementation, improving operational autonomy, and boosting Africa's self-reliant development amid persistent challenges like poverty and infrastructure deficits.[26][18] The statute for AUDA-NEPAD was subsequently developed for adoption in early 2019, marking a shift toward greater integration and accountability within the AU architecture.[24]Recent Realignments and Agenda 2063 Integration (2019–Present)

In July 2019, the African Union's Executive Council officially transformed the NEPAD Planning and Coordinating Agency into the African Union Development Agency-NEPAD (AUDA-NEPAD), establishing it as the AU's first dedicated development agency with enhanced autonomy and a mandate to operationalize continental priorities.[24] This structural realignment, building on approvals from the 2018 AU Summit, shifted governance from the former Heads of State and Government Orientation Committee—disbanded in 2018—to streamlined oversight under the AU Assembly and Executive Council, enabling more agile implementation of development initiatives.[24] AUDA-NEPAD's integration with Agenda 2063 intensified post-2019, positioning it as the primary implementing arm for the AU's 50-year blueprint, with responsibilities spanning knowledge generation, resource mobilization, and high-impact projects in human capital development, industrialization, infrastructure, and natural resource governance.[24] The agency coordinates biennial progress reports alongside the AU Commission, including the inaugural continental assessment covering 31 of 55 member states and subsequent 2020 and 2022 evaluations tracking advancements in socio-economic integration.[27] This alignment emphasized domestication of Agenda 2063 goals at national levels, alongside mechanisms for African-led funding and monitoring to address implementation gaps.[27] The 2020–2023 Strategic Plan marked a pivotal realignment, responding to global mega-trends such as the 2019 African Continental Free Trade Area ratification, Africa's youthful demographics, and infrastructure deficits requiring $130–170 billion in annual financing—far exceeding the $100 billion committed that year.[28] Prioritizing economic competitiveness, fourth industrial revolution technologies, and private sector engagement, the plan directly supported Agenda 2063's first ten-year implementation phase (2014–2023) by fostering regional value chains and addressing low intra-African trade levels.[28] From 2024 onward, AUDA-NEPAD realigned its forthcoming 2024–2028 strategy to the Second Ten-Year Implementation Plan (2024–2033) of Agenda 2063, which introduces seven "moonshot" ambitions—including achieving middle-income status for all member states, deeper continental connectivity, responsive public institutions, and empowered citizenries—to accelerate progress toward resilience and self-reliance.[27] Tools like the Agenda 2063 Digital Platform and Dashboard, managed by AUDA-NEPAD, enable real-time data analytics for evidence-based policymaking, with 38 member states contributing to 2021 reporting cycles.[27] These efforts underscore a causal shift toward catalytic interventions in conflict resolution, value promotion, and global positioning, though empirical progress varies, with reported advancements in health (74%) and education (55%) tempered by persistent financing and governance challenges.[29]Mandate and Core Objectives

Eradication of Poverty and Sustainable Growth

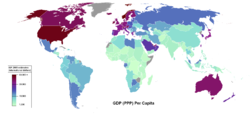

The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) designates the eradication of poverty as one of its foundational objectives, explicitly linked to fostering sustainable economic growth capable of generating employment and raising incomes across African nations. In its 2001 framework document, NEPAD targets halving the proportion of the population living in extreme poverty—defined as less than US$1 per day—by 2015, aligning with the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). At the time, roughly 340 million Africans, comprising half the continent's population, subsisted below this threshold, alongside elevated child mortality rates of 140 per 1,000 live births and an average life expectancy of 54 years.[4][12] To underpin poverty reduction, NEPAD emphasizes achieving and maintaining an annual GDP growth rate of 7 percent over 15 years, predicated on causal mechanisms such as infrastructure investment, human capital enhancement, agricultural productivity gains, and production diversification to shift from commodity dependence toward value-added sectors. Strategies include mobilizing US$64 billion in annual investments—equivalent to 12 percent of Africa's GDP—through debt relief, increased official development assistance (ODA) to 0.7 percent of donor countries' gross national product, and private capital inflows via public-private partnerships and risk mitigation for investors. Governance reforms, including transparency, anti-corruption measures, and political stability, are positioned as prerequisites to attract such resources and ensure pro-poor growth outcomes.[4][12] Sector-specific interventions target root causes of poverty, such as universal primary education by 2015, reducing child mortality by two-thirds and maternal mortality by three-quarters, and boosting health expenditures by US$10 billion annually; in agriculture, priorities encompass smallholder farmer support, irrigation expansion, and research to combat food insecurity affecting vulnerable populations. Regional integration and market access improvements, including stabilization of trade agreements like the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), aim to enhance export competitiveness and domestic revenue for social spending.[4] Under its evolution into the African Union Development Agency-NEPAD (AUDA-NEPAD), these objectives integrate with Agenda 2063 and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), prioritizing welfare upliftment, resilient food systems, energy access, and climate adaptation to sustain long-term growth amid environmental vulnerabilities. Strategic themes extend to gender empowerment and human development, recognizing women's roles in agriculture and informal economies as levers for inclusive poverty alleviation.[30][31] Empirical outcomes reveal partial progress in economic expansion—Africa's GDP growth averaged around 3.4 percent in the late 2010s—but persistent structural barriers, including jobless growth, inequality, and governance deficits, have constrained poverty eradication, with little net decline in lived poverty experiences despite official metrics. By the early 2020s, extreme poverty affected over 400 million Africans, exacerbated by external shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring the need for intensified domestic resource mobilization and policy execution beyond aspirational targets.[32][33][34]Economic Integration and Global Participation

The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD), now operationalized through the African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD), prioritizes economic integration by leveraging Regional Economic Communities (RECs) as foundational structures for continental programs. The eight RECs recognized by the African Union—such as the East African Community (EAC), Southern African Development Community (SADC), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA)—facilitate harmonized policies on trade, infrastructure, and investment to reduce fragmentation and boost intra-regional flows.[16] AUDA-NEPAD provides technical support to these bodies, including capacity-building for policy alignment and project implementation, as seen in initiatives like the Animal Medicine Harmonization (AMRH) program rolled out across five RECs by 2024 to standardize veterinary regulations and enhance agricultural trade.[35][36] A cornerstone of NEPAD's integration efforts is its advocacy for the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), launched via the agreement signed by 44 African Union member states in March 2018 and entering provisional implementation in 2019. AfCFTA aims to eliminate tariffs on 90% of goods traded intra-continentally over a transitional period, potentially increasing Africa's intra-regional trade share from 18% in 2018 to over 50% by 2040, according to projections.[30] AUDA-NEPAD supports AfCFTA rollout through infrastructure prioritization under the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA), which targets cross-border corridors to cut transport costs by up to 30% and stimulate demand for regional exports, particularly in food and manufactured goods.[37][38] This framework addresses barriers like non-tariff measures and regulatory divergences, with AUDA-NEPAD facilitating standardization efforts, such as impact assessments for AfCFTA protocols on investment and digital trade adopted in 2023.[39] On global participation, NEPAD emphasizes positioning Africa as a cohesive player in international trade governance to counter asymmetric dependencies and enhance bargaining power. It promotes private sector-led growth and policy coherence for engaging multilateral forums, including the World Trade Organization (WTO), where African states seek reforms to agricultural subsidies and special treatment provisions.[40] AUDA-NEPAD bolsters this through initiatives strengthening Africa's collective voice, such as supporting the African Union's permanent G20 membership granted in 2023, which amplifies advocacy for equitable global financial flows and trade rules amid rising protectionism.[41][42] Complementary efforts include harmonizing Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with the European Union to minimize trade diversion risks, while fostering South-South partnerships to diversify export markets beyond traditional commodities.[30] These strategies aim to elevate Africa's global economic contribution, projected to rise from under 3% of world trade in 2020 toward sustainable integration driven by value-added exports.[31]Empowerment and Capacity Building

The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD), now integrated into the African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD), identifies capacity building as essential for empowering African institutions and citizens to achieve self-reliant development. This objective focuses on enhancing human resources, institutional frameworks, and knowledge systems to address systemic weaknesses in governance, policy implementation, and technical expertise. AUDA-NEPAD's Capacity Development Programme specifically targets these areas by providing training, advisory services, and strategic tools to African governments, regional bodies, and civil society organizations, guided by continent-wide frameworks that emphasize evidence-based interventions over external dependency.[43] Central to these efforts is Africa's Capacity Development Strategic Framework (CDSF), which outlines six cornerstones: transformative leadership, citizen empowerment, utilization of Africa's potential, skills and resources, alongside institutional strengthening and innovation. The framework prioritizes empowering local actors through skills transfer and resource mobilization, aiming to foster endogenous growth rather than perpetual aid reliance. For instance, citizen empowerment initiatives under CDSF promote participatory governance and community-level decision-making, enabling populations to drive poverty reduction and sustainable resource management.[44] Targeted programs exemplify this mandate, such as the African Biosafety Network of Expertise (ABNE), launched to build regulatory capacities for biotechnology adoption across 19 member states as of 2023. ABNE delivers training in risk assessment and biosafety management, as demonstrated by a 2024 workshop in Rwanda that equipped regulators with tools for evidence-based decision-making on genetically modified crops, thereby enhancing food security without compromising environmental standards. Similarly, socio-economic empowerment drives the Comprehensive Youth and Women Agenda (COYWA), initiated in 2025, which bolsters entrepreneurship and financial inclusion through capacity-building modules for over 10,000 participants annually, focusing on scalable business skills in underserved regions.[45][46][47] Women's empowerment receives dedicated attention via workshops and cooperatives training, such as the April 2024 capacity-building event for African smallholder associations, which trained participants in organizational management and market access strategies to increase agricultural productivity by up to 30% in pilot groups. These initiatives align with NEPAD's foundational emphasis on gender-inclusive capacity building, as articulated in its 2001 framework, which links women's skills enhancement to broader poverty eradication goals. Empirical evaluations, including those from AUDA-NEPAD's internal assessments, indicate improved institutional performance metrics, such as policy execution rates rising 15-20% in beneficiary countries post-training, though challenges persist in scaling amid funding constraints.[48][4]Organizational Structure

Governance and Oversight Mechanisms

The governance of AUDA-NEPAD is anchored in the Heads of State and Government Orientation Committee (HSGOC), which provides strategic leadership, sets policies, priorities, and action programs. Comprising approximately 20 Heads of State and Government elected across the African Union's five regions, the HSGOC ensures alignment with continental development agendas, including Agenda 2063. The committee's chairperson, currently Egypt's President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi since February 2023, reports directly to the AU Assembly on AUDA-NEPAD's progress and challenges, facilitating high-level oversight and decision-making.[49][50][51] An intermediary Steering Committee operates between the HSGOC and the AUDA-NEPAD Agency, handling operational oversight of programs and projects, including terms of reference and implementation monitoring. It includes two representatives each from the five NEPAD initiating countries (Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa) and one from each of 15 AU member states elected regionally on a rotating basis, with observers from entities such as the AU Commission, Regional Economic Communities, African Development Bank, and UN agencies. This structure enforces one-vote-per-member-state rules and promotes accountability through regular reviews.[24][52] Day-to-day leadership and execution fall under the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), who manages the agency's technical and advisory functions, including policy coordination, resource mobilization, knowledge generation, and monitoring/evaluation across eleven core areas. Established as the AU's development agency in 2018, AUDA-NEPAD integrates oversight with the AU's broader structures, emphasizing equitable delivery models linking the AU, Regional Economic Communities, and member states to track outcomes and ensure programmatic excellence.[18][53]Leadership and Operational Bodies

The AUDA-NEPAD Heads of State and Government Orientation Committee (HSGOC) serves as the principal policy-making and oversight body, comprising personal representatives of selected African heads of state and government, with meetings convened approximately four times annually to provide strategic direction and endorse priorities aligned with Agenda 2063.[49] The committee ensures alignment with African Union (AU) objectives, drawing representation from across the continent's regions, including founding NEPAD nations such as Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria, Senegal, and [South Africa](/page/South Africa).[50] As of 2025, the chairperson is H.E. Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, President of the Arab Republic of Egypt, who assumed the role following rotations among member states to guide high-level decisions on development initiatives.[54][55] The Chief Executive Officer (CEO) heads the executive arm, managing daily operations, program implementation, and coordination with AU organs, regional economic communities, and member states. H.E. Nardos Bekele-Thomas, appointed in 2022 as the first woman in the role, oversees technical support, resource mobilization, and innovation incubation across priority sectors like agriculture and infrastructure.[54][56] The CEO reports to the HSGOC and collaborates with the AU Commission chairperson, currently H.E. Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, for policy integration.[54] Supporting governance, the Steering Committee advises on operational execution and comprises up to 20 members, including regional representatives and experts, co-chaired as of 2025 by H.E. Ambassador Ashraf Swelam of Egypt and H.E. Dr. Tah Ahmed Meouloud of Mauritania.[57] Operationally, AUDA-NEPAD's structure features specialized directorates, such as Operations and Knowledge Management, which handle program evaluation, technical backstopping, and country-level mechanisms like Africa Teams—multidisciplinary units integrating government officials, partners, and AUDA-NEPAD staff for localized project delivery and monitoring.[58][59] This framework, approved under AU reforms in 2018, emphasizes efficiency in executing continental projects while fostering partnerships for sustainable outcomes.[60]Partnerships with External Stakeholders

AUDA-NEPAD has forged strategic partnerships with international financial institutions to mobilize resources for infrastructure and development projects, including collaborations with the African Development Bank (AfDB) and Africa50 to establish the Alliance for Green Infrastructure in Africa, launched on February 18, 2022, aimed at scaling up sustainable investments across the continent.[61] These ties extend to engagements with the World Bank and United Nations agencies, facilitating technical assistance and funding aligned with NEPAD's foundational goals of poverty reduction and economic integration.[4] Bilateral partnerships with major economies have been central, particularly through the G8 (now G7) Africa Action Plan adopted in 2002, which committed to supporting NEPAD's priorities in governance, health, and education via enhanced aid coordination and debt relief mechanisms.[62] The European Union has provided programmatic support, including joint initiatives on trade and industrialization, with AUDA-NEPAD prioritizing stakeholder dialogues in Brussels and Berlin to align European investments with African regional value chains as of 2025.[63] Similarly, China has contributed financial and infrastructural backing, emphasizing NEPAD's role in trilateral cooperation frameworks involving Europe, as noted in policy analyses from the early 2010s onward.[64] Private sector and academic collaborations further bolster implementation, such as the 2025 partnership with Georgetown University to develop health financing investment cases and training programs for African institutions.[65] AUDA-NEPAD also coordinates with entities like the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) for harmonizing manufacturing standards, signed to enhance regulatory capacity in pharmaceuticals.[66] These external ties are guided by AU-wide criteria for technical partnerships, emphasizing mutual accountability and alignment with Agenda 2063, though implementation often hinges on African ownership to mitigate donor-driven agendas.[67]Key Programs and Initiatives

Infrastructure and Regional Integration Projects

The Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA), a flagship initiative under AUDA-NEPAD, coordinates cross-border infrastructure to enhance regional connectivity and economic integration across transport, energy, information and communication technology (ICT), and transboundary water sectors.[68] Adopted in 2012 by African Union member states, PIDA identifies 51 priority projects in its Action Plan to address infrastructure deficits estimated at $130-170 billion annually, which hinder continental growth and trade.[69] [70] Key projects include the Douala-Bangui-Ndjamena Corridor, a road-rail initiative linking Cameroon, Central African Republic, and Chad to facilitate faster goods movement and regional trade.[71] In energy, PIDA supports interconnections like the West African Power Pool expansions, aiming for universal access targets such as 60% continental energy coverage by 2040.[72] Transport efforts encompass multimodal corridors, with 16 priority projects endorsed by African heads of state in 2023 for accelerated feasibility studies and funding.[73] ICT components focus on broadband expansion to meet demand for affordable networks, while water projects emphasize shared resource management for irrigation and hydropower.[70] Implementation is bolstered by mechanisms like the NEPAD Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility (NEPAD-IPPF), hosted by the African Development Bank, which has prepared over 100 regional projects since 2008 through technical assistance and donor funding, including a €18.4 million German contribution in March 2025.[74] [75] The Africa50 infrastructure fund, involving 20 African countries and the AfDB, channels investments into PIDA priorities to crowd in private capital.[76] These efforts have contributed to a 16% rise in intra-African exports via improved road and rail links over the past decade, though full realization depends on sustained financing and policy harmonization.[77] PIDA's integration with Agenda 2063 emphasizes resilient, sustainable infrastructure, as highlighted in the 2024 PIDA Week in Addis Ababa, where stakeholders advanced project pipelines amid challenges like funding gaps and geopolitical disruptions.[78] The African Infrastructure Database supports monitoring, providing data on bankable projects across 55 countries to attract investors and track progress toward seamless continental markets.[79]Agriculture, Food Security, and Natural Resources

The Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), established in 2003 as a flagship NEPAD initiative, targets agriculture-led growth to combat poverty and hunger by committing governments to allocate at least 10% of national budgets to the sector and achieve 6% annual agricultural GDP growth, as outlined in the Maputo Declaration.[80] [81] CAADP operates through four pillars: sustainable land and water management to expand arable areas and improve productivity; robust markets and value chains to enhance farmer incomes; resilient food supply systems addressing nutrition and trade; and advancements in science, technology, and innovation for seeds, irrigation, and mechanization.[82] National medium-term investment plans, developed with stakeholder input, guide implementation, supported by a peer review mechanism and biennial reporting to monitor commitments like the Malabo Declaration's 2014 goals for 25% reduction in stunting and doubled smallholder productivity by 2025.[83] [84] In food security, CAADP integrates nutrition-sensitive agriculture, emphasizing smallholder empowerment and value-chain development to reach 25 million farmers with sustainable practices by 2025, while addressing vulnerabilities like climate variability through resilient cropping and post-harvest loss reduction.[85] The 2025 Kampala Declaration launched a 2026-2035 strategy and action plan, projecting a 45% increase in agrifood systems output by 2035 via digital technologies, inclusive growth for smallholders, and climate-resilient practices, building on insights from over a decade of CAADP implementation that improved policy transparency despite uneven budget adherence across countries.[86] [87] [84] NEPAD's natural resources governance complements these efforts by promoting sustainable extraction and environmental stewardship, including programs for climate adaptation, biodiversity conservation, and equitable benefit-sharing from minerals, forests, and fisheries to underpin agricultural viability.[88] The agency's Environment, Climate Change, and Natural Resource Management unit facilitates regional cooperation on issues like land degradation reversal and blue economy development, with initiatives such as capacity-building workshops on resource governance to maximize continental development gains while mitigating ecological risks.[89] [90] These components link natural capital to food systems, aiming to reduce dependency on imports and enhance resilience against shocks like droughts, though progress varies by national execution and external funding.[88]Industrialization and Human Capital Development

AUDA-NEPAD's industrialization efforts center on the Industrialization, Science, Technology and Innovation (ISTI) program, one of its four core investment initiatives, which targets manufacturing, value addition, and technological advancement to drive economic transformation across Africa.[91] This includes promoting import substitution industrialization (ISI) to enhance local production competitiveness and reduce reliance on imports, alongside support for the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the Boosting Intra-African Trade (BIAT) strategy, and the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM) to foster intra-continental trade and industrial growth.[92][30] Additionally, AUDA-NEPAD aligns with the Accelerated Industrial Development for Africa (AIDA) framework, providing tools such as country impact assessment guides to evaluate industrial policies, enabling environments, and sector-specific progress in areas like agro-processing and resource beneficiation.[93] In parallel, human capital development under AUDA-NEPAD emphasizes building skilled workforces through its Human Capital and Institutions Development directorate, which facilitates entrepreneurship training, job creation, and institutional capacity strengthening in partnership with governments, academia, private sectors, and civil society.[94][95] Key programs include the AKILI AI initiative's MSME UpSkill Lab, launched to prepare micro, small, and medium enterprises for investment readiness via digital skills enhancement, and broader efforts in youth empowerment, women's economic participation, social protection, and occupational health to align human resources with industrial demands.[29] These initiatives support national development plans prioritizing skills for sectors like manufacturing and innovation, with a focus on regional integration to address Africa's low R&D investment—often below 1% of GDP in most countries—and limited human capital metrics in innovation outputs.[24][96] The linkage between industrialization and human capital in AUDA-NEPAD's framework underscores causal priorities: skilled labor is essential for sustaining industrial gains, as evidenced by programs targeting priority medical products manufacturing roadmaps to localize production of vaccines and essentials, thereby creating jobs and technical expertise.[97] However, empirical outcomes remain constrained by implementation gaps, with NEPAD's broader human development impacts showing mixed results in economic indicators like job creation rates, where continental industrial contributions hover below 15% of GDP despite targeted interventions.[98] AUDA-NEPAD's Centres of Excellence further integrate these areas by bolstering institutional capacities for policy execution, though verifiable quantification of scaled workforce improvements tied directly to these programs is limited in available assessments.[99]Environmental Sustainability and Climate Resilience

AUDA-NEPAD addresses environmental sustainability by mainstreaming climate resilience into sectors like agriculture, biodiversity, and natural resources, aiming to build adaptive capacities at national and regional levels.[100] This includes strategies for adapting agriculture to climate variability, conserving ecosystems, and promoting sustainable land management to counter desertification and habitat loss.[101] The NEPAD Climate Change Fund has supported 18 adaptation projects across 18 African countries, focusing on agricultural resilience, biodiversity protection, and benefit-sharing mechanisms from genetic resources.[102] These initiatives target vulnerability reduction through capacity-building for local and regional actors, though detailed impact metrics on emission reductions or yield improvements are not comprehensively reported.[103] In December 2015, NEPAD launched the Initiative for the Resilience and Restoration of African Landscapes under the African Landscapes Action Plan, emphasizing forest and ecosystem restoration, biodiversity conservation, climate-smart agriculture, and rangeland management.[104] Partnering with the World Bank Group and World Resources Institute, it aligns with the AFR100 commitment to restore 100 million hectares of degraded land by 2030, seeking to enhance soil fertility, water access, green jobs, and overall economic adaptation to climate stressors.[104] Recent efforts include the November 2024 launch at COP29 of a program integrating climate policies into Africa's food systems, providing technical advisory services, investment pipelines, and partnerships to bolster agri-food infrastructure and trade under the African Continental Free Trade Area.[105] This initiative secured €10 million from Italy via the Technical Cooperation Collaborative to advance climate-smart farming, clean energy for value chains, and resilience for populations facing undernutrition.[105] AUDA-NEPAD also advances resilient infrastructure through knowledge-sharing on climate-proof investments and collaborates via a 2024 memorandum with the Global Center on Adaptation for joint advocacy and capacity-building events.[106] [107] Complementary programs, such as the Gender Climate Change and Agriculture Support Program, deliver training on climate-smart practices to integrate gender considerations into resilience efforts.[108]Empirical Achievements and Impacts

Quantifiable Outcomes in Growth and Integration

The Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA), a flagship initiative under AUDA-NEPAD, has facilitated measurable advances in regional connectivity and economic activity through prioritized cross-border projects in energy, transport, water, and ICT sectors. By the end of 2020, PIDA's first 10-year implementation phase secured USD 82 billion in investment commitments, surpassing the initial target by USD 14 billion, with funding sourced from African Union member states (USD 34.35 billion), infrastructure consortia (USD 19.67 billion), China (USD 19.42 billion), the private sector (USD 2.28 billion), and other contributors (USD 5.88 billion).[109] These investments supported the completion or advancement of projects that enhanced intra-African trade, with exports within the continent rising to 16% of total African trade, attributed to improvements in road and rail networks.[109] Infrastructure gains have directly bolstered integration and productivity. Nearly 30 million people obtained access to electricity, elevating continental access rates to approximately 44%, while ICT broadband penetration surpassed 25%, exceeding PIDA's 10% target and enabling better digital economic linkages.[109] Employment outcomes included 112,900 direct jobs from construction and operations, alongside 49,400 indirect jobs, contributing to localized growth in project-affected regions.[109] In 2023, AUDA-NEPAD mobilized an additional USD 175 million for 22 high-impact PIDA projects, further accelerating integration efforts aligned with the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).[110]| Financing Source | Amount (USD Billion) |

|---|---|

| AU Member States | 34.35 |

| Infrastructure Consortia Africa (ICA) Members | 19.67 |

| China | 19.42 |

| Private Sector | 2.28 |

| Other Sources | 5.88 |

| Total | 82 |