Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

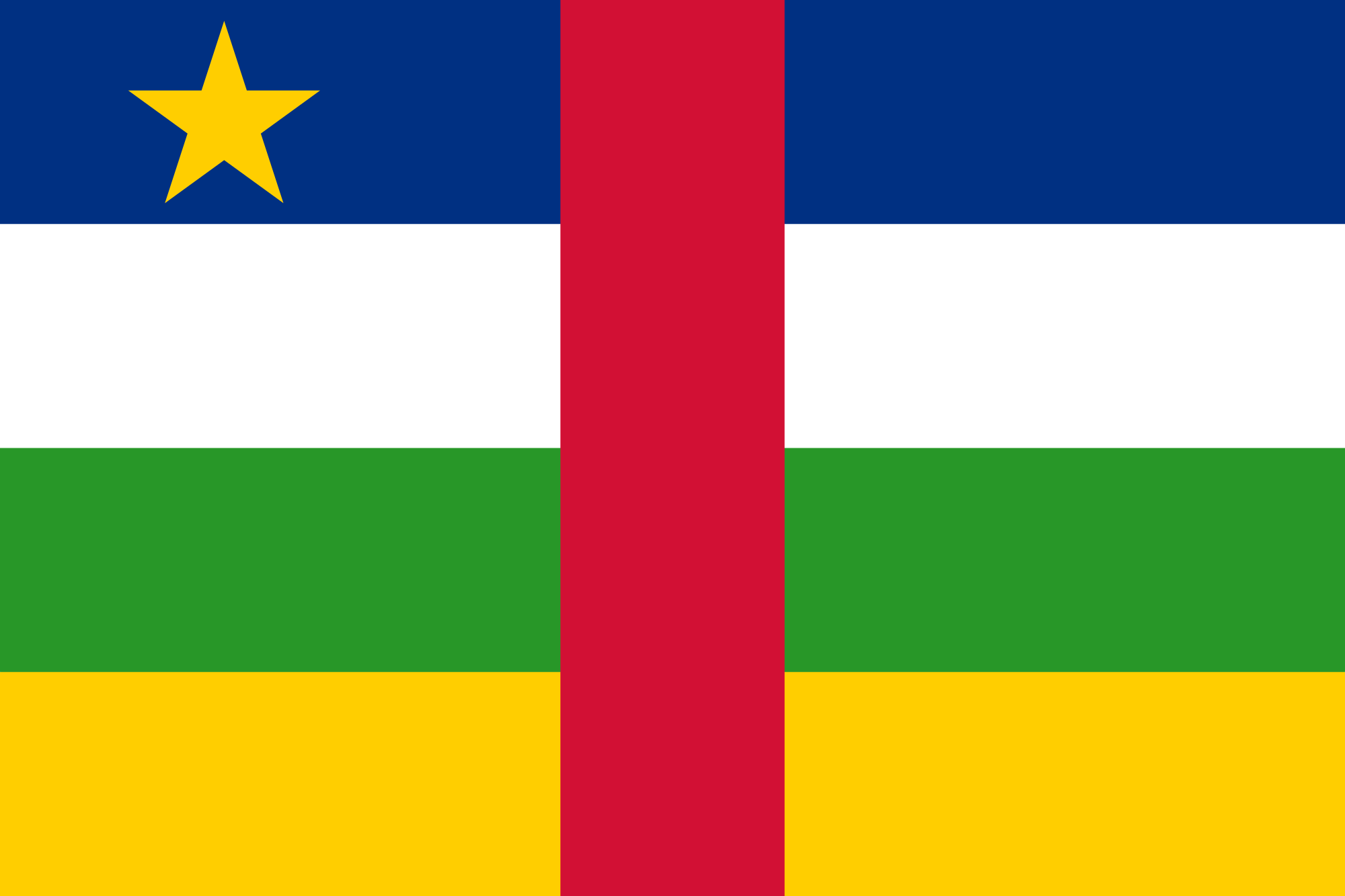

Central African Republic

View on Wikipedia

The Central African Republic (CAR)[a] is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the east, the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the south, the Republic of the Congo to the southwest, and Cameroon to the west. Bangui is the country's capital and largest city, bordering the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Central African Republic covers a land area of about 620,000 square kilometres (240,000 sq mi). As of 2024, it has a population of 5,357,744, consisting of about 80 ethnic groups, and is in the scene of a civil war, which has been ongoing since 2012.[9] Having been a French colony under the name Ubangi-Shari,[b] French is the official language, with Sango, a Ngbandi-based creole language, as the national and co-official language.[1][10]

Key Information

The Central African Republic mainly consists of Sudano-Guinean savanna, but the country also includes a Sahelo-Sudanian zone in the north and an equatorial forest zone in the south. Two-thirds of the country is within the Ubangi River basin (which flows into the Congo), while the remaining third lies in the basin of the Chari, which flows into Lake Chad.

What is today the Central African Republic has been inhabited since at least 8000 BCE. The country's borders were established by France, which began annexing portions to the French Congo in the late 19th century and in 1903 established the separate colony of Ubangi-Shari, part of French Equatorial Africa. After gaining independence from France in 1960, the Central African Republic was ruled by a series of autocratic leaders, including under Jean-Bedel Bokassa who changed the country's name to the Central African Empire and ruled as a monarch from 1976 to 1979.[11] The Central African Republic Bush War began in 2004 and, despite a peace treaty in 2007 and another in 2011, civil war resumed in 2012. The civil war perpetuated the country's poor human rights record: it was characterized by widespread and increasing abuses by various participating armed groups.

Despite its significant mineral deposits and other resources, such as uranium reserves, crude oil, gold, diamonds, cobalt, lumber, and hydropower,[12] as well as significant quantities of arable land, the Central African Republic is among the ten poorest countries in the world, with the lowest GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in the world as of 2017.[13] As of 2023, according to the Human Development Index (HDI), the country had the third-lowest level of human development, ranking 191 out of 193 countries. The country had the second lowest inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI), ranking 164th out of 165 countries.[14] The Central African Republic is also estimated to be the unhealthiest country[15] as well as the worst country to be in for young people.[16] The Central African Republic is a member of the United Nations, the African Union, the Economic Community of Central African States, the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie and the Non-Aligned Movement.

Etymology

[edit]The name of the Central African Republic is derived from the country's geographical location in the central region of Africa and its republican form of government. From 1976 to 1979, the country was known as the Central African Empire.

During the colonial era, the country's name was Ubangi-Shari (French: Oubangui-Chari), a name derived from two major rivers and Central African waterways – Ubangi and Chari. Barthélemy Boganda, the country's first prime minister, favored the name "Central African Republic" over Ubangi-Shari, reportedly because he envisioned a larger union of countries in Central Africa.[17]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

Approximately 10,000 years ago, desertification forced hunter-gatherer societies south into the Sahel regions of northern Central Africa, where some groups settled.[18] Farming began as part of the Neolithic Revolution.[19] Initial farming of white yam progressed into millet and sorghum, and before 3000 BCE[20] the domestication of African oil palm improved the groups' nutrition and allowed for expansion of the local populations.[21] This agricultural revolution, combined with a "Fish-stew Revolution", in which fishing began to take place and the use of boats, allowed for the transportation of goods. Products were often moved in ceramic pots.[citation needed]

The Bouar Megaliths in the western region of the country indicate an advanced level of habitation dating back to the very late Neolithic Era (c. 3500–2700 BCE).[22][23] Ironwork developed in the region around 1000 BCE.[24]

The Ubangian people settled along the Ubangi River in what is today the Central and East Central African Republic while some Bantu people migrated from the southwest of Cameroon.[25]

Bananas arrived in the region during the first millennium BCE[26] and added an important source of carbohydrates to the diet; they were also used in the production of alcoholic beverages. Production of copper, salt, dried fish, and textiles dominated the economic trade in the Central African region.[27]

16th–19th century

[edit]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, slave traders began to raid the region as part of the expansion of the Saharan and Nile River slave routes. Their captives were enslaved and shipped to the Mediterranean coast, Europe, Arabia, the Western Hemisphere, or to the slave ports and factories along the West and North Africa or South along the Ubangui and Congo rivers.[28][29] During the 18th century Bandia-Nzakara Azande peoples established the Bangassou Kingdom along the Ubangi River.[29] In the mid 19th century, the Bobangi people became major slave traders and sold their captives to the Americas using the Ubangi river to reach the coast.[30] In 1875, the Sudanese sultan Rabih az-Zubayr governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day Central African Republic.[31]

French colonial period

[edit]The European invasion of Central African territory began in the late 19th century during the Scramble for Africa.[32] Europeans, primarily the French, Germans, and Belgians, arrived in the area in 1885. France seized and colonized Ubangi-Shari territory in 1894. In 1911 at the Treaty of Fez, France ceded a nearly 300,000 km2 portion of the Sangha and Lobaye basins to the German Empire which ceded a smaller area (in present-day Chad) to France. After World War I France again annexed the territory. Modeled on King Leopold's Congo Free State, concessions were doled out to private companies that endeavored to strip the region's assets as quickly and cheaply as possible before depositing a percentage of their profits into the French treasury. The concessionary companies forced local people to harvest rubber, coffee, and other commodities without pay and held their families hostage until they met their quotas.[33]

In 1920, French Equatorial Africa was established and Ubangi-Shari was administered from Brazzaville.[34] During the 1920s and 1930s the French introduced a policy of mandatory cotton cultivation,[34] a network of roads were built, attempts were made to combat sleeping sickness, and Protestant missions were established to spread Christianity.[35] New forms of forced labour were also introduced and a large number of Ubangians were sent to work on the Congo-Ocean Railway. Through the period of construction until 1934 there was a continual heavy cost in human lives, with total deaths among all workers along the railway estimated in excess of 17,000 of the construction workers, from a combination of both industrial accidents and diseases including malaria.[36] In 1928, a major insurrection, the Kongo-Wara rebellion or 'war of the hoe handle', broke out in Western Ubangi-Shari and continued for several years. The extent of this insurrection, which was perhaps the largest anti-colonial rebellion in Africa during the interwar years, was carefully hidden from the French public because it provided evidence of strong opposition to French colonial rule and forced labour.[37] French colonization in Oubangui-Chari is considered to be the most brutal of the French colonial Empire.[38]

In September 1940, during the Second World War, pro-Gaullist French officers took control of Ubangi-Shari and General Leclerc established his headquarters for the Free French Forces in Bangui.[39] In 1946 Barthélemy Boganda was elected with 9,000 votes to the French National Assembly, becoming the first representative of the Central African Republic in the French government. Boganda maintained a political stance against racism and the colonial regime but gradually became disheartened with the French political system and returned to the Central African Republic to establish the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (Mouvement pour l'évolution sociale de l'Afrique noire, MESAN) in 1950.[31]

Since independence (1960–present)

[edit]In the Ubangi-Shari Territorial Assembly election in 1957, MESAN captured 347,000 out of the total 356,000 votes[40] and won every legislative seat,[41] which led to Boganda being elected president of the Grand Council of French Equatorial Africa and vice-president of the Ubangi-Shari Government Council.[42] Within a year, he declared the establishment of the Central African Republic and served as the country's first prime minister. MESAN continued to exist, but its role was limited.[43] The Central African Republic was granted autonomy within the French Community on 1 December 1958, a status which meant it was still counted as part of the French Empire in Africa.[44]

After Boganda's death in a plane crash on 29 March 1959, his cousin, David Dacko, took control of MESAN. Dacko became the country's first president when the Central African Republic formally received independence from France at midnight on 13 August 1960, a date celebrated by the country's Independence Day holiday.[45] Dacko threw out his political rivals, including Abel Goumba, former Prime Minister and leader of Mouvement d'évolution démocratique de l'Afrique centrale (MEDAC), whom he forced into exile in France. With all opposition parties suppressed by November 1962, Dacko declared MESAN as the official party of the state.[46]

Bokassa and the Central African Empire (1965–1979)

[edit]

On 31 December 1965, Dacko was overthrown in the Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état by Colonel Jean-Bédel Bokassa, who suspended the constitution and dissolved the National Assembly. President Bokassa declared himself President for Life in 1972 and named himself Emperor Bokassa I of the Central African Empire (as the country was renamed) on 4 December 1976. A year later, Emperor Bokassa crowned himself in an expensive ceremony.[11]

In April 1979, young students protested against Bokassa's decree that all school pupils were required to buy uniforms from a company owned by one of his wives. The government violently suppressed the protests, killing 100 children and teenagers. Bokassa might have been personally involved in some of the killings.[47] In September 1979, France overthrew Bokassa and restored Dacko to power (subsequently restoring the official name of the country and the original government to the Central African Republic). Dacko, in turn, was again overthrown in a coup by General André Kolingba on 1 September 1981.[48]

Central African Republic under Kolingba

[edit]Kolingba suspended the constitution and ruled with a military junta until 1985. He introduced a new constitution in 1986 which was adopted by a nationwide referendum. Membership in his new party, the Rassemblement Démocratique Centrafricain (RDC), was voluntary. In 1987 and 1988, semi-free elections to parliament were held, but Kolingba's two major political opponents, Abel Goumba and Ange-Félix Patassé, were not allowed to participate.[49]

By 1990, inspired by the fall of the Berlin Wall, a pro-democracy movement arose. Pressure from the United States, France, and from a group of locally represented countries and agencies called GIBAFOR (France, the US, Germany, Japan, the EU, the World Bank, and the United Nations) finally led Kolingba to agree, in principle, to hold free elections in October 1992 with help from the UN Office of Electoral Affairs. After using the excuse of alleged irregularities to suspend the results of the elections as a pretext for holding on to power, President Kolingba came under intense pressure from GIBAFOR to establish a "Conseil National Politique Provisoire de la République" (Provisional National Political Council, CNPPR) and to set up a "Mixed Electoral Commission", which included representatives from all political parties.[49]

When a second round of elections were finally held in 1993, again with the help of the international community coordinated by GIBAFOR, Ange-Félix Patassé won in the second round of voting with 53% of the vote while Goumba won 45.6%. Patassé's party, the Mouvement pour la Libération du Peuple Centrafricain (MLPC) or Movement for the Liberation of the Central African People, gained a plurality (relative majority) but not an absolute majority of seats in parliament, which meant Patassé's party required coalition partners.[49]

Patassé government (1993–2003)

[edit]Patassé purged many of the Kolingba elements from the government and Kolingba supporters accused Patassé's government of conducting a "witch hunt" against the Yakoma. A new constitution was approved on 28 December 1994 but had little impact on the country's politics. In 1996–1997, reflecting steadily decreasing public confidence in the government's erratic behavior, three mutinies against Patassé's administration were accompanied by widespread destruction of property and heightened ethnic tension. During this time (1996), the Peace Corps evacuated all its volunteers to neighboring Cameroon. To date, the Peace Corps has not returned to the Central African Republic. The Bangui Agreements, signed in January 1997, provided for the deployment of an inter-African military mission, to the Central African Republic and re-entry of ex-mutineers into the government on 7 April 1997. The inter-African military mission was later replaced by a U.N. peacekeeping force (MINURCA). Since 1997, the country has hosted almost a dozen peacekeeping interventions, earning it the title of "world champion of peacekeeping".[33]

In 1998, parliamentary elections resulted in Kolingba's RDC winning 20 out of 109 seats. The next year, however, in spite of widespread public anger in urban centers over his corrupt rule, Patassé won a second term in the presidential election.[50]

On 28 May 2001, rebels stormed strategic buildings in Bangui in an unsuccessful coup attempt. The army chief of staff, Abel Abrou, and General François N'Djadder Bedaya were killed, but Patassé regained the upper hand by bringing in at least 300 troops of the Congolese rebel leader Jean-Pierre Bemba and Libyan soldiers.[51]

In the aftermath of the failed coup, militias loyal to Patassé sought revenge against rebels in many neighborhoods of Bangui and incited unrest including the murder of many political opponents. Eventually, Patassé came to suspect that General François Bozizé was involved in another coup attempt against him, which led Bozizé to flee with loyal troops to Chad. In March 2003, Bozizé launched a surprise attack against Patassé, who was out of the country. Libyan troops and some 1,000 soldiers of Bemba's Congolese rebel organization failed to stop the rebels and Bozizé's forces succeeded in overthrowing Patassé.[52]

Civil wars

[edit]

François Bozizé suspended the constitution and named a new cabinet, which included most opposition parties. Abel Goumba was named vice-president. Bozizé established a broad-based National Transition Council to draft a new constitution, and announced that he would step down and run for office once the new constitution was approved.[53]

In 2004, the Central African Republic Bush War began as forces opposed to Bozizé took up arms against his government. In May 2005, Bozizé won the presidential election, which excluded Patassé, and in 2006 fighting continued between the government and the rebels.[54] In November 2006, Bozizé's government requested French military support to help them repel rebels who had taken control of towns in the country's northern regions.[55] Though the initial public details of the agreement pertained to logistics and intelligence, by December the French assistance included airstrikes by Dassault Mirage 2000 fighters against rebel positions.[56][57]

The Syrte Agreement in February and the Birao Peace Agreement in April 2007 called for a cessation of hostilities, the billeting of FDPC fighters and their integration with FACA, the liberation of political prisoners, the integration of FDPC into government, an amnesty for the UFDR, its recognition as a political party, and the integration of its fighters into the national army. Several groups continued to fight but other groups signed on to the agreement or similar agreements with the government (e.g., UFR on 15 December 2008). The only major group not to sign an agreement at the time was the CPJP, which continued its activities and signed a peace agreement with the government on 25 August 2012.[58]

In 2011, Bozizé was reelected in an election which was widely considered fraudulent.[12]

In November 2012, Séléka, a coalition of rebel groups, took over towns in the northern and central regions of the country. These groups eventually reached a peace deal with Bozizé's government in January 2013, involving a power-sharing government.[12] The deal later broke down, and the rebels seized the capital in March 2013 and Bozizé fled the country.[59][60]

Michel Djotodia took over as president. Prime Minister Nicolas Tiangaye requested a UN peacekeeping force from the UN Security Council and on 31 May former President Bozizé was indicted for crimes against humanity and incitement to genocide.[61] By the end of the year, there were international warnings of a "genocide"[62][63] and fighting was largely reprisal attacks on civilians by Seleka's predominantly Muslim fighters and Christian militias called "anti-balaka".[64] By August 2013, there were reports of over 200,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs).[65][66]

On 18 February 2014, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called on the UN Security Council to immediately deploy 3,000 troops to the country, bolstering the 6,000 African Union soldiers and 2,000 French troops already in the country, to combat civilians being murdered in large numbers. The Séléka government was said to be divided,[67] and in September 2013, Djotodia officially disbanded Seleka, but many rebels refused to disarm, becoming known as ex-Seleka, and veered further out of government control.[64] It is argued that the focus of the initial disarmament efforts exclusively on the Seleka inadvertently handed the anti-Balaka the upper hand, leading to the forced displacement of Muslim civilians by anti-Balaka in Bangui and western Central African Republic.[33]

On 11 January 2014, Michael Djotodia and Nicolas Tiengaye resigned as part of a deal negotiated at a regional summit in neighboring Chad.[68] Catherine Samba-Panza was elected interim president by the National Transitional Council,[69] becoming the first ever female Central African president. On 23 July 2014, following Congolese mediation efforts, Séléka and anti-balaka representatives signed a ceasefire agreement in Brazzaville.[70] By the end of 2014, the country was de facto partitioned with the anti-Balaka in the southwest and ex-Seleka in the northeast.[33] In March 2015, Samantha Power, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, said 417 of the country's 436 mosques had been destroyed, and Muslim women were so scared of going out in public they were giving birth in their homes instead of going to the hospital.[71] On 14 December 2015, Séléka rebel leaders declared an independent Republic of Logone.[72]

Touadéra government (2016–present)

[edit]

Presidential elections were held in December 2015. As no candidate received more than 50% of the vote, a second round of elections was held on 14 February 2016 with run-offs on 31 March 2016.[73][74] In the second round of voting, former Prime Minister Faustin-Archange Touadéra was declared the winner with 63% of the vote, defeating Union for Central African Renewal candidate Anicet-Georges Dologuélé, another former Prime Minister.[75] While the elections suffered from many potential voters being absent as they had taken refuge in other countries, the fears of widespread violence were ultimately unfounded, and the African Union regarded the elections as successful.[76]

Touadéra was sworn in on 30 March 2016. No representatives of the Seleka rebel group or the "anti-balaka" militias were included in the subsequently formed government.[77]

Presidential elections were held on 27 December 2020.[78] Former president François Bozizé announced his candidacy but was rejected by the Constitutional Court of the country, which held that Bozizé did not satisfy the "good morality" requirement for candidates because of an international warrant and United Nations sanctions against him for alleged assassinations, torture and other crimes.[79]

As large parts of the country were at the time controlled by armed groups, the election could not be conducted in many areas of the country.[80][81] Some 800 of the country's polling stations, or 14% of the total, were closed due to violence.[82] Three Burundian peacekeepers were killed and an additional two were wounded during the run-up to the election.[83][84] President Faustin-Archange Touadéra was reelected.[85] Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group have supported President Faustin-Archange Touadéra in the fight against rebels. Russia's Wagner group has been accused of harassing and intimidating civilians.[86][87] In December 2022, Roger Cohen wrote in The New York Times, "Wagner shock troops form a Praetorian Guard for Mr. Touadéra, who is also protected by Rwandan forces, in return for an untaxed license to exploit and export the Central African Republic's resources" and "one Western ambassador called the Central African Republic...a 'vassal state' of the Kremlin."[88]

Geography

[edit]

The Central African Republic is a landlocked nation within the interior of the African continent. It is bordered by Cameroon, Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the Congo. The country lies between latitudes 2° and 11°N, and longitudes 14° and 28°E.[89]

Much of the country consists of flat or rolling plateau savanna approximately 500 metres (1,640 ft) above sea level. In addition to the Fertit Hills in the northeast of the Central African Republic, there are scattered hills in the southwest regions. In the northwest is the Yade Massif, a granite plateau with an altitude of 348 metres (1,143 ft). The Central African Republic contains six terrestrial ecoregions: Northeastern Congolian lowland forests, Northwestern Congolian lowland forests, Western Congolian swamp forests, East Sudanian savanna, Northern Congolian forest-savanna mosaic, and Sahelian Acacia savanna.[90]

At 622,984 square kilometres (240,535 sq mi), the Central African Republic is the world's 44th-largest country.[91]

Much of the southern border is formed by tributaries of the Congo River; the Mbomou River in the east merges with the Uele River to form the Ubangi River, which also comprises portions of the southern border. The Sangha River flows through some of the western regions of the country, while the eastern border lies along the edge of the Nile River watershed.[89]

Around 36% of the country is covered by forest, with the densest parts generally located in the southern regions. The forests are highly diverse and include commercially important species of Ayous, Sapelli, and Sipo.[92] The deforestation rate is about 0.4% per annum, and lumber poaching is commonplace.[93] The Central African Republic had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 9.28/10, ranking it seventh globally out of 172 countries.[94]

In 2008, Central African Republic was the world's least light pollution affected country.[95]

The focal point of the Bangui Magnetic Anomaly, one of the largest magnetic anomalies on Earth, is located within the country's capital.[96]

Climate

[edit]

The climate of the Central African Republic is generally tropical, with a wet season that lasts from June to September in the northern regions of the country, and from May to October in the south. During the wet season, rainstorms are an almost daily occurrence, and early morning fog is commonplace. Maximum annual precipitation is approximately 1,800 millimetres (71 in) in the upper Ubangi region.[97]

The northern areas are hot and humid from February to May,[98] but can be subject to the hot, dry, and dusty trade wind known as the Harmattan. The southern regions have a more equatorial climate, but they are subject to desertification, while the extreme northeast regions of the country are a steppe.[99]

Biodiversity

[edit]

In the southwest, the Dzanga-Sangha National Park is located in a rain forest area. The country is noted for its population of forest elephants and western lowland gorillas. In the north, the Manovo-Gounda St Floris National Park is well-populated with wildlife, including leopards, lions, cheetahs and rhinos, and the Bamingui-Bangoran National Park is located in the northeast of the Central African Republic. The parks have been seriously affected by the activities of poachers, particularly those from Sudan, over the past two decades.[100]

In the Central African Republic forest cover is around 36% of the total land area, equivalent to 22,303,000 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, down from 23,203,000 hectares (ha) in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 22,301,000 hectares (ha) and planted forest covered 2,000 hectares (ha). Of the naturally regenerating forest 9% was reported to be primary forest (consisting of native tree species with no clearly visible indications of human activity). For the year 2015, 91% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership and 9% private ownership.[101][102] In 2021, the rate of deforestation in the Central African Republic increased by 71%.[103]

Government and politics

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Recent developments and Russian influence. (December 2022) |

Politics in the Central African Republic formally take place in a framework of a presidential republic. In this system, the President is the head of state, with a Prime Minister as head of government. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and parliament.[12]

Changes in government have occurred in recent years by three methods: violence, negotiations, and elections. A new constitution was approved by voters in a referendum held on 5 December 2004. The government was rated 'Partly Free' from 1991 to 2001 and from 2004 to 2013.[104] V-Dem Democracy Indices described Central African Republic as autocratizing in 2024.[105]

The president is elected by popular vote for a six-year term, and the prime minister is appointed by the president. The president also appoints and presides over the Council of Ministers, which initiates laws and oversees government operations. However, as of 2018 the official government is not in control of large parts of the country, which are governed by rebel groups.[106] Acting president since April 2016 is Faustin-Archange Touadéra who followed the interim government under Catherine Samba-Panza, interim prime minister André Nzapayeké.[10]

The National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale) has 140 members, elected for a five-year term using the two-round (or run-off) system.[12]

As in many other former French colonies, the Central African Republic's legal system is based on French law.[107] The Supreme Court, or Cour Suprême, is made up of judges appointed by the president. There is also a Constitutional Court, and its judges are also appointed by the president.[12]

Freedom of speech is addressed in the country's constitution, but there have been incidents of government intimidation of the media.[108] A report by the International Research & Exchanges Board's media sustainability index noted that "the country minimally met objectives, with segments of the legal system and government opposed to a free media system".[108]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

The Central African Republic is divided into 20 administrative prefectures (préfectures), two of which are economic prefectures (préfectures économiques); the prefectures are further divided into 84 sub-prefectures (sous-préfectures).[109]

The prefectures are Bamingui-Bangoran, Bangui, Basse-Kotto, Haute-Kotto, Haut-Mbomou, Kémo, Lobaye, Lim-Pendé, Mambéré, Mambéré-Kadéï, Mbomou, Nana-Mambéré, Ombella-M'Poko, Ouaka, Ouham, Ouham-Fafa, Ouham-Pendé, and Vakaga. The economic prefectures are Nana-Grébizi and Sangha-Mbaéré.[109]

Foreign relations

[edit]

The Central African Republic is heavily dependent on foreign aid, and numerous NGOs provide services that the government does not provide.[110] In 2019, over US$100 million in foreign aid was spent in the country, mostly on humanitarian assistance.[111]

In 2006, due to ongoing violence, over 50,000 people in the country's northwest were at risk of starvation,[112] but this was averted due to assistance from the United Nations.[113] On 8 January 2008, the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon declared that the Central African Republic was eligible to receive assistance from the Peacebuilding Fund.[114] Three priority areas were identified: first, the reform of the security sector; second, the promotion of good governance and the rule of law; and third, the revitalization of communities affected by conflicts. On 12 June 2008, the Central African Republic requested assistance from the UN Peacebuilding Commission,[115] which was set up in 2005 to help countries emerging from conflict avoid devolving back into war or chaos.[116]

In response to concerns of a potential genocide, a peacekeeping force – the International Support Mission to the Central African Republic (MISCA) – was authorized in December 2013. This African Union force of 6,000 personnel was accompanied by the French Operation Sangaris.[117]

In 2017, the Central African Republic signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[118]

In August 2025, Russia demanded that the Central African Republic pay its Africa Corps for armed protection rather than use the private mercenaries Wagner Group.[119]

Human rights

[edit]The 2009 Human Rights Report by the United States Department of State noted that human rights in the Central African Republic were poor and expressed concerns over numerous government abuses.[108] The U.S. State Department alleged that major human rights abuses such as extrajudicial executions by security forces, torture, beatings, and rape of suspects and prisoners occurred with impunity. It also alleged harsh and life-threatening conditions in prison and detention centers, arbitrary arrest, prolonged pretrial detention and denial of a fair trial, restrictions on freedom of movement, official corruption, and restrictions on workers' rights.[108]

The State Department report also cites widespread mob violence, the prevalence of female genital mutilation, discrimination against women and pygmies, human trafficking, forced labor, and child labor.[120] Freedom of movement is limited in the northern part of the country "because of actions by state security forces, armed bandits, and other non-state armed entities", and due to fighting between government and anti-government forces, many people have been internally displaced.[121]

Violence against children and women in relation to accusations of witchcraft has also been cited as a serious problem in the country.[122][123][124] Witchcraft is a criminal offense under the penal code.[122]

Approximately 68% of girls are married before they turn 18,[125] and the United Nations's Human Development Index ranked the country 188th out of 188 countries surveyed.[126] The Bureau of International Labor Affairs has also mentioned it in its last edition of the List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor.

Economy

[edit]

The per capita income of the Republic is often listed as being approximately $400 a year, one of the lowest in the world, but this figure is based mostly on reported sales of exports and largely ignores the unregistered sale of foods, locally produced alcoholic beverages, diamonds, ivory, bushmeat, and traditional medicine.[127]

The currency of the Central African Republic is the CFA franc, which is accepted across the former countries of French West Africa and trades at a fixed rate to the euro. Diamonds constitute the country's most important export, accounting for 40–55% of export revenues, but it is estimated that between 30% and 50% of those produced each year leave the country clandestinely.[127] On 27 April 2022,[128] Bitcoin (BTC) was adopted as an additional legal tender. Lawmakers unanimously adopted a bill that made Bitcoin legal tender alongside the CFA franc and legalized the use of cryptocurrencies. President Faustin-Archange Touadéra signed the measure into law, said his chief of staff Obed Namsio. After an extraordinary meeting on 6 May 2022, COBAC published DECISION D-071-2022[129] in which it banned the use of crypto currency. It subsequently repealed its status as legal tender.[130]

Agriculture is dominated by the cultivation and sale of food crops such as cassava, peanuts, maize, sorghum, millet, sesame, and plantain. The annual growth rate of real GDP is slightly above 3%. The importance of food crops over exported cash crops is indicated by the fact that the total production of cassava, the staple food of most Central Africans, ranges between 200,000 and 300,000 tonnes a year, while the production of cotton, the principal exported cash crop, ranges from 25,000 to 45,000 tonnes a year. Food crops are not exported in large quantities, but still constitute the principal cash crops of the country because Central Africans derive far more income from the periodic sale of surplus food crops than from exported cash crops such as cotton or coffee.[127] Much of the country is self-sufficient in food crops; however, livestock development is hindered by the presence of the tsetse fly.[131]

The Republic's primary import partner is France (17.1%). Other imports come from the United States (12.3%), India (11.5%), and China (8.2%). Its largest export partner is France (31.2%), followed by Burundi (16.2%), China (12.5%), Cameroon (9.6%), and Austria (7.8%).[12]

The Central African Republic is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA). In the 2009 World Bank Group's report Doing Business, it was ranked 183rd out of 183 as regards 'ease of doing business', a composite index which takes into account regulations that 'enhance' business activity and those that restrict it.[132]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]

Two trans-African automobile routes pass through the Central African Republic: the Tripoli-Cape Town Highway and the Lagos-Mombasa Highway. Bangui is the transport hub of the Central African Republic. As of 1999, eight roads connected the city to other main towns in the country, Cameroon, Chad, and South Sudan; of these, only the toll roads are paved. During the rainy season from July to October, some roads are impassable.[133][134]

River ferries sail from the river port at Bangui to Brazzaville and Zongo. The river can be navigated most of the year between Bangui and Brazzaville. From Brazzaville, goods are transported by rail to Pointe-Noire, Congo's Atlantic port.[135] The river port handles the overwhelming majority of the country's international trade and has a cargo handling capacity of 350,000 tons; it has 350 metres (1,150 ft) length of wharfs and 24,000 square metres (260,000 sq ft) of warehousing space.[133]

Bangui M'Poko International Airport is Central African Republic's only international airport. As of June 2014 it had regularly scheduled direct flights to Brazzaville, Casablanca, Cotonou, Douala, Kinshasa, Lomé, Luanda, Malabo, N'Djamena, Paris, Pointe-Noire, and Yaoundé.[citation needed]

Since at least 2002 there have been plans to connect Bangui by rail to the Transcameroon Railway.[136]

Energy

[edit]The Central African Republic primarily uses hydroelectricity as there are few other low cost resources for generating electricity.[137] Access to electricity is very limited with 15.6% of the total population having electrification, 34.6% in urban areas and 1.5% in rural areas.[138]

Communications

[edit]Presently, the Central African Republic has active television services, radio stations, internet service providers, and mobile phone carriers; Socatel is the leading provider for both internet and mobile phone access throughout the country. The primary governmental regulating bodies of telecommunications are the Ministère des Postes and Télécommunications et des Nouvelles Technologies. In addition, the Central African Republic receives international support on telecommunication related operations from ITU Telecommunication Development Sector (ITU-D) within the International Telecommunication Union to improve infrastructure.[139]

Demographics

[edit]

The population of the Central African Republic has almost quadrupled since independence. In 1960, the population was 1,232,000; as of a 2021 UN estimate, it is approximately 5,457,154.[140][141]

The United Nations estimates that approximately 4% of the population aged between 15 and 49 is HIV positive.[142] Only 3% of the country has antiretroviral therapy available, compared to 17% coverage in the neighboring countries of Chad and the Republic of the Congo.[143][needs update]

The nation comprises over 80 ethnic groups, each having its own language. The largest ethnic groups are the Baggara Arabs, Baka, Banda, Bayaka, Fula, Gbaya, Kara, Kresh, Mbaka, Mandja, Ngbandi, Sara, Vidiri, Wodaabe, Yakoma, Yulu, and Zande, with others including Europeans of mostly French descent.[12] The most common ethnic groups are Gbaya (Baya) (28.8%) and Banda (22.9%), comprising together slightly over half of the country's population in 2003.[144]

| Rank | Name | Prefecture | Pop. | Rank | Name | Prefecture | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bangui | Bangui | 622,771 | 11 | Kaga-Bandoro | Nana-Grébizi | 24,661 | ||

| 2 | Bimbo | Bangui | 124,176 | 12 | Sibut | Kémo | 22,419 | ||

| 3 | Berbérati | Mambéré-Kadéï | 76,918 | 13 | Mbaïki | Lobaye | 22,166 | ||

| 4 | Carnot | Mambéré-Kadéï | 45,421 | 14 | Bozoum | Ouham-Pendé | 20,665 | ||

| 5 | Bambari | Ouaka | 41,356 | 15 | Paoua | Ouham-Pendé | 17,370 | ||

| 6 | Bouar | Nana-Mambéré | 40,353 | 16 | Batangafo | Ouham | 16,420 | ||

| 7 | Bossangoa | Ouham | 36,478 | 17 | Kabo | Ouham | 16,279 | ||

| 8 | Bria | Haute-Kotto | 35,204 | 18 | Bocaranga | Ouham-Pendé | 15,744 | ||

| 9 | Bangassou | Mbomou | 31,553 | 19 | Ippy | Ouaka | 15,196 | ||

| 10 | Nola | Sangha-Mbaéré | 29,181 | 20 | Alindao | Basse-Kotto | 14,401 | ||

Languages

[edit]The Central African Republic's two official languages are French and Sango (also spelled Sangho),[146] a creole developed as an inter-ethnic lingua franca based on the local Ngbandi language. The Central African Republic is one of the few African countries to have granted official status to an African language.

Religion

[edit]

According to the 2003 national census, 80.3% of the population was Christian (51.4% Protestant and 28.9% Roman Catholic), 10% was Muslim and 4.5 percent other religious groups, with 5.5 percent having no religious beliefs.[147] More recent work from the Pew Research Center estimated that, as of 2010, Christians constituted 89.8% of the population (60.7% Protestant and 28.5% Catholic) while Muslims made up 8.9%.[148][149] The Catholic Church claims over 1.5 million adherents, approximately one-third of the population.[150] Indigenous belief (animism) is also practiced, and many indigenous beliefs are incorporated into Christian and Islamic practice.[151] A UN director described religious tensions between Muslims and Christians as being high.[152]

There are many missionary groups operating in the country, including Lutherans, Baptists, Catholics, Grace Brethren, and Jehovah's Witnesses. While these missionaries are predominantly from the United States, France, Italy, and Spain, many are also from Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and other African countries. Large numbers of missionaries left the country when fighting broke out between rebel and government forces in 2002–3, but many of them have now returned to continue their work.[153]

According to Overseas Development Institute research, during the crisis ongoing since 2012, religious leaders have mediated between communities and armed groups; they also provided refuge for people seeking shelter.[117]

Education

[edit]

Public education in the Central African Republic is free and is compulsory from ages 6 to 14.[154] However, approximately half of the adult population of the country is illiterate.[155] The two institutions of higher education in the Central African Republic are the University of Bangui, a public university located in Bangui, which includes a medical school; and Euclid University, an international university.[156][157]

Health

[edit]

The largest hospitals in the country are located in the Bangui district. As a member of the World Health Organization, the Central African Republic receives vaccination assistance, such as a 2014 intervention for the prevention of a measles epidemic.[158] In 2007, female life expectancy at birth was 48.2 years, and male life expectancy at birth was 45.1 years.[159]

Women's health is poor in the Central African Republic. As of 2010[update], the country had the fourth highest maternal mortality rate in the world.[160] The total fertility rate in 2014 was estimated at 4.46 children born/woman.[12] Approximately 25% of women had undergone female genital mutilation.[161] Many births in the country are guided by traditional birth attendants, who often have little or no formal training.[162]

Malaria is endemic in the Central African Republic and one of the leading causes of death.[163] According to 2009 estimates, the HIV/AIDS prevalence rate is about 4.7% of the adult population (ages 15–49).[164] This is in general agreement with the 2016 United Nations estimate of approximately 4%.[142] Government expenditure on health was US$20 (PPP) per person in 2006[159] and 10.9% of total government expenditure in 2006.[159] There was only around 1 physician for every 20,000 people in 2009.[165]

In the 2024 Global Hunger Index, Central African Rep. ranks 119th out of the 127 countries with sufficient data to calculate 2024 GHI scores. With a score of 31.5[166]

Culture

[edit]

The nation comprises over 80 ethnic groups, each having its own language. The largest ethnic groups are the Baggara Arabs, Baka, Banda, Bayaka, Fula, Gbaya, Kara, Kresh, Mbaka, Mandja, Ngbandi, Sara, Vidiri, Wodaabe, Yakoma, Yulu, and Zande, with others including Europeans of mostly French descent.

Sports

[edit]Football is the country's most popular sport. The national football team is governed by the Central African Football Federation and stages matches at the Barthélemy Boganda Stadium.[167]

Basketball also is popular[168][169] and its national team won the African Championship twice and was the first Sub-Saharan African team to qualify for the Basketball World Cup, in 1974.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^

- Sango: Ködörösêse tî Bêafrîka, Sango pronunciation: [kōdōrōsésè tí bé.àfríkà]

- French: République centrafricaine, IPA: [ʁepyblik sɑ̃tʁafʁikɛn]; abbreviated RCA or Centrafrique, [sɑ̃tʁafʁik][8]

- ^ French: Oubangui-Chari

References

[edit]- ^ a b Samarin, William J. (2000). "The Status of Sango in Fact and Fiction: On the One-Hundredth Anniversary of its Conception". In McWhorter, John H. (ed.). Language Change and Language Contact in Pidgins and Creoles. Creole language library. Vol. 21. John Benjamins. pp. 301–34. ISBN 9789027252432.

- ^ "National Profiles". www.thearda.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ "Central African Republic". The World Factbook (2025 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2023. (Archived 2023 edition.)

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (CF)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Gini Index". World Bank Group. Retrieved 23 January 2025.

- ^ "HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2025 A matter of choice People and possibilities in the age of AI" (PDF). hdr.undp.org.

- ^ Which side of the road do they drive on? Archived 14 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Brian Lucas. August 2005. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ^ "Central African Republic – CAR – Country Profile – Nations Online Project". www.nationsonline.org. Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Mudge, Lewis (11 December 2018), "Central African Republic: Events of 2018", World Report 2019: Rights Trends in Central African Republic, archived from the original on 30 May 2019, retrieved 13 June 2024

- ^ a b "Central African Republic country profile". BBC News. 20 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2025.

- ^ a b c 'Cannibal' dictator Bokassa given posthumous pardon Archived 1 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. 3 December 2010

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Central African Republic", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 1 February 2024, archived from the original on 24 December 2018, retrieved 10 February 2024

- ^ World Economic Outlook Database, January 2018 Archived 3 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine, International Monetary Fund Archived 14 February 2006 at Archive-It. Database updated on 12 April 2017. Accessed on 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Human Development Index and its components" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ "These are the world's unhealthiest countries – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 25 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ "Central African Republic worst country in the world for young people – study". Thomson Reuters Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Palmer, Brian (9 March 2012). "Why Does the Central African Republic Have Such a Boring Name?". Slate. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ McKenna, p. 4

- ^ Brierley, Chris; Manning, Katie; Maslin, Mark (1 October 2018). "Pastoralism may have delayed the end of the green Sahara". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 4018. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.4018B. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06321-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6167352. PMID 30275473.

- ^ Fran Osseo-Asare (2005) Food Culture in Sub Saharan Africa. Greenwood. ISBN 0313324883. p. xxi

- ^ McKenna, p. 5

- ^ Methodology and African Prehistory by, UNESCO. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa, p. 548

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Les mégalithes de Bouar" Archived 3 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. UNESCO.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (2002). The civilizations of Africa : a history to 1800. Oxford: James Currey. p. 161. ISBN 0-85255-476-1. OCLC 59451060.

- ^ Mozaffari, Mehdi (2002), "Globalization, civilizations and world order: A world-constructivist approach", Globalization and Civilizations, Taylor & Francis, pp. 24–50, doi:10.4324/9780203217979_chapter_2, ISBN 978-0-203-29460-4

- ^ Mbida, Christophe M.; Van Neer, Wim; Doutrelepont, Hugues; Vrydaghs, Luc (15 March 1999). "Evidence for banana cultivation and animal husbandry during the first millennium BCE in the forest of southern Cameroon". Journal of Archaeological Science. 27 (2): 151–162. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0447.

- ^ McKenna, p. 10

- ^ Central African Republic Foreign Policy and Government Guide (World Strategic and Business Information Library). Vol. 1. International Business Publications. 7 February 2007. p. 47. ISBN 978-1433006210. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ a b Alistair Boddy-Evans. Central Africa Republic Timeline – Part 1: From Prehistory to Independence (13 August 1960), A Chronology of Key Events in Central Africa RepublicArchived 23 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. About.com

- ^ "Central African Republic Archived 13 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b "Rābiḥ az-Zubayr | African military leader". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ French Colonies – Central African Republic Archived 21 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Discoverfrance.net. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d "One day we will start a big war". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ a b Thomas O'Toole (1997) Political Reform in Francophone Africa. Westview Press. p. 111

- ^ Gardinier, David E. (1985). "Vocational and Technical Education in French Equatorial Africa (1842–1960)". Proceedings of the Meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society. 8. Michigan State University Press: 113–123. ISSN 0362-7055. JSTOR 42952135.

- ^ "In pictures: Malaria train, Mayomba forest". news.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ^ Kalck, Pierre. (2005). Historical dictionary of the Central African Republic (3rd ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4913-5. OCLC 55487416.

- ^ "Key dates for the Central African Republic". rfi.fr. 11 August 2010. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ Central African Republic: The colonial era – Britannica Online Encyclopedia Archived 12 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Cherkaoui, Said El Mansour (1991). "Central African Republic". In Olson, James S. (ed.). Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism. Greenwood. p. 122. ISBN 0-313-26257-8.

- ^ Kalck, p. xxxi.

- ^ Kalck, p. 90.

- ^ Kalck, p. 136.

- ^ Langer's Encyclopedia of World History, page 1268.

- ^ "Central African Republic". African Union Development Agency. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Kalck, p. xxxii.

- ^ "'Good old days' under Bokassa? Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. 2 January 2009

- ^ Prial, Frank J. (2 September 1981). "Army Tropples Leader of Central African Republic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 May 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ a b c "Central African Republic – Discover World". www.discoverworld.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "EISA Central African Republic: 1999 Presidential election results". www.eisa.org.za. African Democracy Encyclopaedia Project. October 2010. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ International Crisis Group. "Central African Republic: Anatomy of a Phantom State" (PDF). CrisisGroup.org. International Crisis Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ "Central African Republic History". DiscoverWorld.com. 2018. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Bozize to step down after transitional period". The New Humanitarian. 28 April 2003. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (10 December 2006). "On the Run as War Crosses Another Line in Africa". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "CAR hails French pledge on rebels". BBC. 14 November 2006. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ "Central African Republic: Hundreds flee Birao as French jets strike – Central African Republic". ReliefWeb. 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "French planes attack CAR rebels". BBC. 30 November 2006. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ "PA-X: Peace Agreements Database". www.peaceagreements.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Central African Republic president flees capital amid violence, official says". CNN. 24 March 2013. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Lydia Polgreen (25 March 2013). "Leader of Central African Republic Fled to Cameroon, Official Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "CrisisWatch N°117" Archived 20 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. crisisgroup.org.

- ^ "UN warning over Central African Republic genocide risk". BBC News. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 19 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ "France says Central African Republic on verge of genocide". Reuters. 21 November 2013. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ a b Smith, David (22 November 2013) Unspeakable horrors in a country on the verge of genocide Archived 2 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian. Retrieved 23 November 2013

- ^ "CrisisWatch N°118" Archived 20 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. crisisgroup.org.

- ^ "CrisisWatch N°119" Archived 20 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. crisisgroup.org.

- ^ Mark Tran (14 August 2013). "Central African Republic crisis to be scrutinised by UN security council". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "CAR interim President Michel Djotodia resigns". BBC News. 11 January 2014. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ Paul-Marin Ngoupana (11 January 2014). "Central African Republic's capital tense as ex-leader heads into exile". Reuters. Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ "RCA : signature d’un accord de cessez-le-feu à Brazzaville Archived 29 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine". VOA. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Anna, Cara (17 March 2015). "Almost all 436 Central African Republic mosques destroyed: U.S. diplomat". CTVNews. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Rebel declares autonomous state in Central African Republic Archived 18 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Reuters. 16 December 2015.

- ^ Centrafrique : Le corps électoral convoqué le 14 février pour le 1er tour des législatives et le second tour de la présidentielle Archived 4 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine (in French), RJDH, 28 January 2016

- ^ New Central African president takes on a country in ruins Archived 4 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine ENCA, 28 March 2016

- ^ CAR presidential election: Faustin Touadera declared winner Archived 28 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 20 February 2016

- ^ "Central African Republic: Freedom in the World 2020 Country Report". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Vincent Duhem, "Centrafrique : ce qu’il faut retenir du nouveau gouvernement dévoilé par Touadéra" Archived 1 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Jeune Afrique, 13 April 2016 (in French).

- ^ "Code électoral de la République Centrafricaine (Titre 2, Chapitre 1, Art. 131)" (PDF). Droit-Afrique.com (in French). 20 August 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "RCA : présidentielle du 27 décembre, la Cour Constitutionnelle publie la liste définitive des candidats". 3 December 2020. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "Centrafrique : " ces élections, c'est une escroquerie politique ", dixit le candidat à la présidentielle Martin Ziguélé". 29 December 2020. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "Élections en Centrafrique: la légitimité du scrutin, perturbé en province, divise à Bangui". 29 December 2020. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "CAR violence forced closure of 800 polling stations: Commission". aljazeera.com. Al Jazeera English. 28 December 2020. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Three UN peacekeepers killed in CAR ahead of Sunday's elections". www.aljazeera.com. Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera. 26 December 2020. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "UN chief condemns attacks against peacekeepers in the Central African Republic". UN News. United Nations News Service. 26 December 2020. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Central African Republic President Touadéra wins re-election". 4 January 2021. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ "Wagner Group: Why the EU is alarmed by Russian mercenaries in Central Africa". BBC News. 19 December 2021. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Roger; Lima, Mauricio (24 December 2022). "Putin Wants Fealty, and He's Found It in Africa". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Roger Cohen. Africa's Allegiance to Putin. New York Times, International Edition; 31 Dec 2022 / 1 Jan 2023, page A1+.

- ^ a b Moen, John. "Geography of Central African Republic, Landforms – World Atlas". www.worldatlas.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ "UNData app". data.un.org. Archived from the original on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Sold Down the River (English)" Archived 13 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine. forestsmonitor.org.

- ^ "The Forests of the Congo Basin: State of the Forest 2006". Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2010.. CARPE 13 July 2007

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ National Geographic Magazine, November 2008

- ^ L. A. G. Antoine; W. U. Reimold; A. Tessema (1999). "The Bangui Magnetic Anomaly Revisited" (PDF). Proceedings 62nd Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting. 34: A9. Bibcode:1999M&PSA..34Q...9A. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Central African Republic: Country Study Guide volume 1, p. 24.

- ^ Ward, Inna, ed. (2007). Whitaker's Almanack (139th ed.). London: A & C Black. p. 796. ISBN 978-0-7136-7660-0.

- ^ Peek, Philip M.; Yankah, Kwesi (March 2004). African Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135948733. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "Wildlife of northern Central African Republic in danger". phys.org. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Terms and Definitions FRA 2025 Forest Resources Assessment, Working Paper 194. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2023.

- ^ "Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020, Central African Republic". Food Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- ^ "Deforestation Surges in World's No. 2 Tropical Forest". Bloomberg. 10 November 2022.

- ^ "FIW Score". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "Democracy Report 2025, 25 Years of Autocratization – Democracy Trumped?" (PDF). Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- ^ Losh, Jack (26 March 2018). "Rebels in the Central African Republic are filling the void of an absent government". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Legal System". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 22 June 2014. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d 2009 Human Rights Report: Central African Republic . U.S. Department of State, 11 March 2010.

- ^ a b Ngoulou, Fridolin (11 December 2020). "La Centrafrique dispose désormais de 20 préfectures et de 84 sous-préfectures". oubanguimedias.com. Oubangui Medias. Archived from the original on 21 September 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ Jauer, Kersten (July 2009). "Stuck in the 'recovery gap': the role of humanitarian aid in the Central African Republic". Humanitarian Practice Network. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Central African Republic | ForeignAssistance.gov". www.foreignassistance.gov. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ CAR: Food shortages increase as fighting intensifies in the northwest Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. irinnews.org, 29 March 2006

- ^ "Central African Republic Executive Summary 2006" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Central African Republic Peacebuilding Fund – Overview[usurped]. United Nations.

- ^ "Peacebuilding Commission Places Central African Republic on Agenda; Ambassador Tells Body 'CAR Will Always Walk Side By Side With You, Welcome Your Advice'". United Nations. 2 July 2008. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Mandate | UNITED NATIONS PEACEBUILDING". www.un.org. United Nations. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ a b Veronique Barbelet (2015) Central African Republic: addressing the protection crisis Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ "Russia asks Central African Republic to replace Wagner with state-run Africa Corps and pay for it". AP News. 6 August 2025. Retrieved 25 August 2025.

- ^ "Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor – Central African Republic" Archived 3 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. dol.gov.

- ^ "2010 Human Rights Report: Central African Republic". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ a b "UNICEF WCARO – Media Centre – Central African Republic: Children, not witches". Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ "Report: Accusations of child witchcraft on the rise in Africa". Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ UN human rights chief says impunity major challenge in run-up to elections in Central African Republic Archived 27 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. ohchr.org. 19 February 2010

- ^ "Child brides around the world sold off like cattle". USA Today. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ "Central African Republic". International Human Development Indicators. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ a b c "Central African Republic – Systematic Country Diagnostic : Priorities for Ending Poverty and Boosting Shared Prosperity". The World Bank. Washington, D.C.: 1–96 19 June 2019. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020 – via documents.worldbank.org/.

- ^ "Central African Republic adopts bitcoin as legal currency". news.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "COBAC - Decision COBAC D-071-2022 on cryptocurrency".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions on Central African Republic". International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 11 August 2023. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ Gouteux, J. P.; Blanc, F.; Pounekrozou, E.; Cuisance, D.; Mainguet, M.; D'Amico, F.; Le Gall, F. (1994). "Tsetse and livestock in Central African Republic: retreat of Glossina morsitans submorsitans (Diptera, Glossinidae)". Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique. 87 (1): 52–56. ISSN 0037-9085. PMID 8003908.

- ^ Doing Business 2010. Central African Republic. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; The World Bank. 2009. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-7961-5. ISBN 978-0-8213-7961-5.

- ^ a b Eur, pp. 200–202

- ^ Graham Booth; G. R McDuell; John Sears (1999). World of Science: 2. Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-19-914698-7. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Central African Republic: Finance and trade". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Eur, p. 185

- ^ "Hydropower in Central Africa – Hydro News Africa – ANDRITZ HYDRO". www.andritz.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Central African Republic Energy". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ "Regional Regulatory Associations in Africa". www.itu.int. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950–2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Central African Republic". Unaids.org. 29 July 2008. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ ANNEX 3: Country progress indicators Archived 9 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine. 2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. unaids.org

- ^ "Central African Republic: People and Society". The World Factbook. Retrieved 23 January 2025.

- ^ "Central African Republic". City Population. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ "Central African Republic 2016 Constitution". Constitute. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2010". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ "Table: Christian Population as Percentages of Total Population by Country". Pew Research Center. 19 December 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Table: Muslim Population by Country". Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Central African Republic, Statistics by Diocese". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Central African Republic". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ "Central African Republic: Religious tinderbox". BBC News. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Central African Republic. International Religious Freedom Report 2006". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ "Central African Republic". Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor (2001). Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Central African Republic – Statistics". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 23 June 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Accueil – Université de Bangui". www.univ-bangui.org. 18 August 2022. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ University, EUCLID. "EUCLID (Euclid University) | Official Site". www.euclid.int. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ "WHO – Health in Central African Republic". Archived from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ a b c "Human Development Report 2009 – Central African Republic". Hdrstats.undp.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Country Comparison :: Maternal mortality rate". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ "WHO – Female genital mutilation and other harmful practices". Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ "Mother and child health in Central African Republic". Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ "Malaria – one of the leading causes of death in the Central African Republic". Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ CIA World Factbook: HIV/AIDS – adult prevalence rate Archived 21 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Cia.gov. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "WHO Country Offices in the WHO African Region – WHO | Regional Office for Africa". Afro.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Global Hunger Index Scores by 2024 GHI Rank". Global Hunger Index (GHI) - peer-reviewed annual publication designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger at the global, regional, and country levels. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ "Central African Republic - TheSportsDB.com". www.thesportsdb.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ Country Profile – Central African Republic-Sports and Activities Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Indo-African Chamber of Commerce and Industry Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Central African Republic — Things to Do Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, iExplore Retrieved 24 September 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Eur (31 October 2002). Africa South of the Sahara 2003. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-85743-131-5.

- Kalck, Pierre (2004). Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic.

- McKenna, Amy (2011). The History of Central and Eastern Africa. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1615303229.

- Balogh, Besenyo, Miletics, Vogel: La République Centrafricaine

Further reading

[edit]- Doeden, Matt, Central African Republic in Pictures (Twentyfirst Century Books, 2009).

- Petringa, Maria, Brazza, A Life for Africa (2006). ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0.

- Titley, Brian, Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa, 2002.

- Woodfrok, Jacqueline, Culture and Customs of the Central African Republic (Greenwood Press, 2006).

External links

[edit]Overviews

[edit]- Country Profile from BBC News

- Central African Republic. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Central African Republic from UCB Libraries GovPubs

Wikimedia Atlas of the Central African Republic

Wikimedia Atlas of the Central African Republic- Key Development Forecasts for the Central African Republic from International Futures

News

[edit]Other

[edit]- Central African Republic at Humanitarian and Development Partnership Team (HDPT)

- Johann Hari in Birao, Central African Republic. "Inside France's Secret War" from The Independent, 5 October 2007

- - Central African Republic Population-Worldometer

Central African Republic

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Origins and historical usage of the name

The territory now known as the Central African Republic was established as the French colony of Ubangi-Shari on December 29, 1903, with its name derived from the Ubangi River along its southern boundary and the Chari River to the north, which served as principal waterways and administrative delimiters during French colonization of the region.[9][10] This designation persisted as part of French Equatorial Africa until the mid-20th century, reflecting the colonial emphasis on fluvial geography rather than indigenous ethnonyms or historical polities.[11] Following the French constitutional referendum of September 1958, which dismantled the French Equatorial Federation, the Territorial Assembly of Ubangi-Shari declared the territory's autonomy as the Central African Republic (République centrafricaine) on December 1, 1958; the name explicitly denoted its central position on the African continent and its adoption of a republican governmental structure, distinguishing it from the broader Central Africa subregion encompassing multiple states.[11][1] This self-descriptive nomenclature avoided ethnic or river-based labels, prioritizing geographic centrality—though the country lies slightly north of Africa's geometric midpoint—and post-colonial republican identity over prior colonial or pre-colonial terms.[1] The name Central African Republic was formalized upon full independence from France on August 13, 1960, and has remained the official designation in international usage since, with the exception of a brief interlude from December 4, 1976, to September 20, 1979, when Jean-Bédel Bokassa's regime rebranded it the Central African Empire to evoke monarchical grandeur amid his self-coronation as emperor.[11][12] Restoration of the republican name in 1979 aligned with the deposition of Bokassa and reversion to civilian rule, underscoring the term's association with non-monarchical governance amid the country's recurrent political upheavals.[1]History

Pre-colonial societies and trade networks

The territory of the modern Central African Republic hosted early human settlements by foraging societies dating back approximately 10,000 years, transitioning to more structured communities evidenced by the Bouar megaliths, constructed between 3500 and 2700 BCE, which suggest capabilities in quarrying, transport, and possibly ritual monument-building.[13] [14] Bantu-speaking migrants arrived progressively from the late 1st millennium BCE through the early 1st millennium CE, originating from West-Central Africa and spreading agricultural techniques, iron smelting, and village-based social structures that assimilated or displaced indigenous forager groups like the Aka pygmies.[15] This expansion established dominant ethnic clusters including the Gbaya (about 33% of pre-colonial population), Banda (27%), Mandja (13%), and Sara (10%), who organized into patrilineal clans with segmentary lineages led by lineage heads and age-grade systems for warfare and labor.[16] [17] Political forms remained largely decentralized, featuring small chiefdoms where authority derived from kinship, wealth in cattle or slaves, and spiritual mediation rather than hereditary monarchies; exceptions arose in the northeast among Ubangi-Shari riverine peoples, where Zande-derived Bandia conquerors founded sultanates like Bangassou around 1800, imposing tribute extraction and cavalry-based rule over subject villages.[18] [19] Regional trade networks integrated these societies into wider exchanges, channeling ivory tusks, rubber, and captives southward via Ubangi River canoes to Congo Basin markets or eastward through caravan paths to Nile Valley and Indian Ocean ports, bartering for salt, copper, and textiles from northern Sahelian intermediaries or Swahili coast entrepôts; participation in slave exports, peaking in the 19th century under Arab-influenced raids, supplied labor for plantations while importing firearms that escalated inter-group conflicts.[1][20]French colonial rule (1894–1960)