Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neutron temperature

View on Wikipedia

| Science with neutrons |

|---|

|

| Foundations |

| Neutron scattering |

| Other applications |

|

| Infrastructure |

|

| Neutron facilities |

The neutron detection temperature, also called the neutron energy, indicates a free neutron's kinetic energy, usually given in electron volts. The term temperature is used, since hot, thermal and cold neutrons are moderated in a medium with a certain temperature. The neutron energy distribution is then adapted to the Maxwell distribution known for thermal motion. Qualitatively, the higher the temperature, the higher the kinetic energy of the free neutrons. The momentum and wavelength of the neutron are related through the de Broglie relation. The long wavelength of slow neutrons allows for the large cross section.[1]

Neutron energy distribution ranges

[edit]The precise boundaries of neutron energy ranges are not well defined, and differ between sources,[2] but some common names and limits are given in the following table.

| Neutron energy | Neutron wavelength | Energy range | Production | Usage | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-7eV | > 500 Å | Ultracold neutrons | Moderation by liquid helium or solid deuterium | Neutron optics, lifetime, electric dipole moment, condensed matter research | Storage times >15 minutes in bottles.[5] |

| 0.0 – 25 meV | ≈ 2 - 6 Å | Cold (slow) neutrons | Moderation by liquid deuterium, liquid para-hydrogen or solid methane | Neutron Scattering | |

| 25 meV | ≈ 1.8 Å | Thermal neutrons (at 20 °C) | Room temperature moderators | Nuclear fission reactors, transmutation, breeding blankets | Room temperature |

| 25 meV–0.4 eV | ≈ 1.8 - 0.45 Å | Epithermal neutrons | Reduced moderation | Above room temperature | |

| 10–300 eV | ≈ 0.09 - 0.016 Å | Resonance neutrons | Susceptible to non-fission capture by 238U. | ||

| 1–20 MeV | ≈ 900 - 200 fm | Fast neutrons | Nuclear fission reactions, nuclear fusion reactions | Fast reactors, transuranium burnup, breeding blankets, neutron bombs | |

| > 20 MeV | < 100 fm | Ultrafast neutrons | Nuclear spallation from particle accelerator ions | Fast neutron therapy, fission research | Relativistic |

The following is a detailed classification:

Thermal

[edit]A thermal neutron is a free neutron with a kinetic energy of about 0.025 eV (about 4.0×10−21 J or 2.4 MJ/kg, hence a speed of 2.19 km/s), which is the energy corresponding to the most probable speed at a temperature of 290 K (17 °C or 62 °F), the mode of the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution for this temperature, Epeak = k T.

After a number of collisions with nuclei (scattering) in a medium (neutron moderator) at this temperature, those neutrons which are not absorbed reach about this energy level.

Thermal neutrons have a different and sometimes much larger effective neutron absorption cross-section for a given nuclide than fast neutrons, and can therefore often be absorbed more easily by an atomic nucleus, creating a heavier, often unstable isotope of the chemical element as a result. This event is called neutron activation.

Epithermal

[edit]Epithermal neutrons are those with energies above the thermal energy at room temperature (i.e. 0.025 eV). Depending on the context, this can encompass all energies up to fast neutrons (as in e.g.[6][7]).

This includes neutrons produced by conversion of accelerated protons in a pitcher-catcher geometry [8]

Cold (slow) neutrons

[edit]

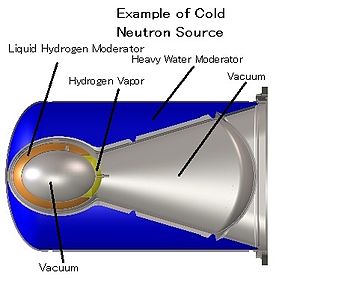

Cold neutrons are thermal neutrons that have been equilibrated in a very cold substance such as liquid deuterium. Such a cold source is placed in the moderator of a research reactor or spallation source. Cold neutrons are particularly valuable for neutron scattering experiments.[9]

Ultracold neutrons are produced by inelastic scattering of cold neutrons in substances with a low neutron absorption cross section at a temperature of a few kelvins, such as solid deuterium[10] or superfluid helium.[11] An alternative production method is the mechanical deceleration of cold neutrons exploiting the Doppler shift.[12][13]

Ultra-cold neutrons reflect at all angles of incidence. This is because their momentum is comparable to the optical potential of materials. This effect is used to store them in bottles and study their fundamental properties[5][14] e.g. lifetime, neutron electrical-dipole moment etc... The main limitations of the use of slow neutrons is the low flux and the lack of efficient optical devices (in the case of CN and VCN). Efficient neutron optical components are being developed and optimized to remedy this lack.[15]

Fast

[edit]A fast neutron is a free neutron with a kinetic energy level close to 1 MeV (100 TJ/kg), hence a speed of 14,000 km/s or higher. They are named fast neutrons to distinguish them from lower-energy thermal neutrons, and high-energy neutrons produced in cosmic showers or accelerators. Fast neutrons are produced by nuclear processes:

- Nuclear fission: thermal fission of 235

U produces neutrons with a mean energy of 2 MeV (200 TJ/kg, i.e. 20,000 km/s),[16] which qualifies as "fast". However, the energy spectrum of these neutrons approximately follows a right-skewed Watt distribution ,[17][18] with a range of 0 to about 17 MeV,[16] a median of 1.6 MeV,[19] and a mode of 0.75 MeV.[16] A significant proportion of fission neutrons do not qualify as "fast" even by the 1 MeV criterion. - Spontaneous fission is a mode of radioactive decay for some heavy nuclides. Examples include plutonium-240 and californium-252.

- Nuclear fusion: deuterium–tritium fusion produces neutrons of 14.1 MeV (1400 TJ/kg, i.e. 52,000 km/s, 17.3% of the speed of light) that can easily fission uranium-238 and other non-fissile actinides.

- Neutron emission occurs in situations in which a nucleus contains enough excess neutrons that the separation energy of one or more neutrons becomes negative (i.e. excess neutrons "drip" out of the nucleus). Unstable nuclei of this sort will often decay in less than one second.

Fast neutrons are usually undesirable in a steady-state nuclear reactor because most fissile fuel has a higher reaction rate with thermal neutrons. Fast neutrons can be rapidly changed into thermal neutrons via a process called moderation. This is done through numerous collisions with (in general) slower-moving and thus lower-temperature particles like atomic nuclei and other neutrons. These collisions will generally speed up the other particle and slow down the neutron and scatter it. Ideally, a room temperature neutron moderator is used for this process. In reactors, heavy water, light water, or graphite are typically used to moderate neutrons.

Fission energy neutrons

[edit]A fast neutron is a free neutron with a kinetic energy level close to 1 MeV (1.6×10−13 J), hence a speed of ~14000 km/s (~ 5% of the speed of light). They are named fission energy or fast neutrons to distinguish them from lower-energy thermal neutrons, and high-energy neutrons produced in cosmic showers or accelerators. Fast neutrons are produced by nuclear processes such as nuclear fission. Neutrons produced in fission, as noted above, have a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution of kinetic energies from 0 to ~14 MeV, a mean energy of 2 MeV (for 235U fission neutrons), and a mode of only 0.75 MeV, which means that more than half of them do not qualify as fast (and thus have almost no chance of initiating fission in fertile materials, such as 238U and 232Th).

Fast neutrons can be made into thermal neutrons via a process called moderation. This is done with a neutron moderator. In reactors, typically heavy water, light water, or graphite are used to moderate neutrons.

Fusion neutrons

[edit]

D–T (deuterium–tritium) fusion is the fusion reaction that produces the most energetic neutrons, with 14.1 MeV of kinetic energy and traveling at 17% of the speed of light. D–T fusion is also the easiest fusion reaction to ignite, reaching near-peak rates even when the deuterium and tritium nuclei have only a thousandth as much kinetic energy as the 14.1 MeV that will be produced.

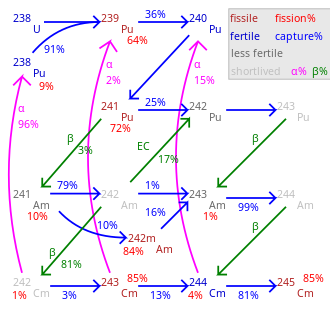

14.1 MeV neutrons have about 10 times as much energy as fission neutrons, and they are very effective at fissioning even non-fissile heavy nuclei. These high-energy fissions also produce more neutrons on average than fissions by lower-energy neutrons. D–T fusion neutron sources, such as proposed tokamak power reactors, are therefore useful for transmutation of transuranic waste. 14.1 MeV neutrons can also produce neutrons by knocking them loose from nuclei.

On the other hand, these very high-energy neutrons are less likely to simply be captured without causing fission or spallation. For these reasons, nuclear weapon design extensively uses D–T fusion 14.1 MeV neutrons to cause more fission. Fusion neutrons are able to cause fission in ordinarily non-fissile materials, such as depleted uranium (uranium-238), and these materials have been used in the jackets of thermonuclear weapons. Fusion neutrons also can cause fission in substances that are unsuitable or difficult to make into primary fission bombs, such as reactor grade plutonium. This physical fact thus causes ordinary non-weapons grade materials to become of concern in certain nuclear proliferation discussions and treaties.

Other fusion reactions produce much less energetic neutrons. D–D fusion produces a 2.45 MeV neutron and helium-3 half of the time and produces tritium and a proton but no neutron the rest of the time. D–3He fusion produces no neutron.

Intermediate-energy neutrons

[edit]

A fission energy neutron that has slowed down but not yet reached thermal energies is called an epithermal neutron.

Cross sections for both capture and fission reactions often have multiple resonance peaks at specific energies in the epithermal energy range. These are of less significance in a fast-neutron reactor, where most neutrons are absorbed before slowing down to this range, or in a well-moderated thermal reactor, where epithermal neutrons interact mostly with moderator nuclei, not with either fissile or fertile actinide nuclides. But in a partially moderated reactor with more interactions of epithermal neutrons with heavy metal nuclei, there are greater possibilities for transient changes in reactivity that might make reactor control more difficult.

Ratios of capture reactions to fission reactions are also worse (more captures without fission) in most nuclear fuels such as plutonium-239, making epithermal-spectrum reactors using these fuels less desirable, as captures not only waste the one neutron captured but also usually result in a nuclide that is not fissile with thermal or epithermal neutrons, though still fissionable with fast neutrons. The exception is uranium-233 of the thorium cycle, which has good capture-fission ratios at all neutron energies.

High-energy neutrons

[edit]High-energy neutrons have much more energy than fission energy neutrons and are generated as secondary particles by particle accelerators or in the atmosphere from cosmic rays. These high-energy neutrons are extremely efficient at ionization and far more likely to cause cell death than X-rays or protons.[20][21]

Fast-neutron reactor and thermal-neutron reactor compared

[edit]Most fission reactors are thermal-neutron reactors that use a neutron moderator to slow down ("thermalize") the neutrons produced by nuclear fission. Moderation substantially increases the fission cross section for fissile nuclei such as uranium-235 or plutonium-239. In addition, uranium-238 has a much lower capture cross section for thermal neutrons, allowing more neutrons to cause fission of fissile nuclei and propagate the chain reaction, rather than being captured by 238U. The combination of these effects allows light water reactors to use low-enriched uranium. Heavy water reactors and graphite-moderated reactors can even use natural uranium as these moderators have much lower neutron capture cross sections than light water.[22]

An increase in fuel temperature also raises uranium-238's thermal neutron absorption by Doppler broadening, providing negative feedback to help control the reactor. When the coolant is a liquid that also contributes to moderation and absorption (light water or heavy water), boiling of the coolant will reduce the moderator density, which can provide positive or negative feedback (a positive or negative void coefficient), depending on whether the reactor is under- or over-moderated.

Intermediate-energy neutrons have poorer fission/capture ratios than either fast or thermal neutrons for most fuels. An exception is the uranium-233 of the thorium cycle, which has a good fission/capture ratio at all neutron energies.

Fast-neutron reactors use unmoderated fast neutrons to sustain the reaction, and require the fuel to contain a higher concentration of fissile material relative to fertile material (uranium-238). However, fast neutrons have a better fission/capture ratio for many nuclides, and each fast fission releases a larger number of neutrons, so a fast breeder reactor can potentially "breed" more fissile fuel than it consumes.

Fast reactor control cannot depend solely on Doppler broadening or on negative void coefficient from a moderator. However, thermal expansion of the fuel itself can provide quick negative feedback. Perennially expected to be the wave of the future, fast reactor development has been nearly dormant with only a handful of reactors built in the decades since the Chernobyl accident due to low prices in the uranium market, although there is now a revival with several Asian countries planning to complete larger prototype fast reactors in the next few years.[when?]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ de Broglie, Louis. "On the Theory of Quanta" (PDF). aflb.ensmp.fr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ H. Tomita, C. Shoda, J. Kawarabayashi, T. Matsumoto, J. Hori, S. Uno, M. Shoji, T. Uchida, N. Fukumotoa and T. Iguchia, Development of epithermal neutron camera based on resonance-energy-filtered imaging with GEM, 2012, quote: "Epithermal neutrons have energies between 1 eV and 10 keV and smaller nuclear cross sections than thermal neutrons."

- ^ Carron, N.J. (2007). An Introduction to the Passage of Energetic Particles Through Matter. p. 308. Bibcode:2007ipep.book.....C.

- ^ "Neutron Energy". www.nuclear-power.net. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Introduction", Ultracold Neutrons, WORLD SCIENTIFIC, pp. 1–9, 2019-09-23, doi:10.1142/9789811212710_0001, ISBN 978-981-12-1270-3, S2CID 243745548, retrieved 2022-11-11

- ^ W. C. Feldman et al., Fluxes of Fast and Epithermal Neutrons from Lunar Prospector: Evidence for Water Ice at the Lunar Poles.Science281,1496-1500(1998).DOI:10.1126/science.281.5382.1496

- ^ Mirfayzi, S.R., Yogo, A., Lan, Z. et al. Proof-of-principle experiment for laser-driven cold neutron source. Sci Rep 10, 20157 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77086-y

- ^ Akifumi YOGO, Developments of Laser-Driven Neutron Source based on "Pitcher-Catcher" Method, The Review of Laser Engineering, 2018, Volume 46, Issue 10, Pages 582-, Released on J-STAGE December 18, 2020. https://doi.org/10.2184/lsj.46.10_582

- ^ brian.maranville@nist.gov (2017-04-17). "How neutrons are useful". NIST. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- ^ B. Lauss (May 2012). "Startup of the high-intensity ultracold neutron source at the Paul Scherrer Institute". Hyperfine Interact. 211 (1): 21–25. arXiv:1202.6003. Bibcode:2012HyInt.211...21L. doi:10.1007/s10751-012-0578-7. S2CID 119164071.

- ^ R. Golub & J. M. Pendlebury (1977). "The interaction of Ultra-Cold Neutrons (UCN) with liquid helium and a superthermal UCN source". Phys. Lett. A. 62 (5): 337–339. Bibcode:1977PhLA...62..337G. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(77)90434-0.

- ^ A. Steyerl; H. Nagel; F.-X. Schreiber; K.-A. Steinhauser; R. Gähler; W. Gläser; P. Ageron; J. M. Astruc; W. Drexel; G. Gervais & W. Mampe (1986). "A new source of cold and ultracold neutrons". Phys. Lett. A. 116 (7): 347–352. Bibcode:1986PhLA..116..347S. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(86)90587-6.

- ^ Stefan Döge; Jürgen Hingerl & Christoph Morkel (Feb 2020). "Measured velocity spectra and neutron densities of the PF2 ultracold-neutron beam ports at the Institut Laue–Langevin". Nucl. Instrum. Methods A. 953 163112. arXiv:2001.04538. Bibcode:2020NIMPA.95363112D. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2019.163112. S2CID 209942845. Archived from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Jenke, Tobias; Bosina, Joachim; Micko, Jakob; Pitschmann, Mario; Sedmik, René; Abele, Hartmut (2021-06-01). "Gravity resonance spectroscopy and dark energy symmetron fields". The European Physical Journal Special Topics. 230 (4): 1131–1136. arXiv:2012.07472. Bibcode:2021EPJST.230.1131J. doi:10.1140/epjs/s11734-021-00088-y. ISSN 1951-6401. S2CID 229156429.

- ^ Hadden, Elhoucine; Iso, Yuko; Kume, Atsushi; Umemoto, Koichi; Jenke, Tobias; Fally, Martin; Klepp, Jürgen; Tomita, Yasuo (2022-05-24). "Nanodiamond-based nanoparticle-polymer composite gratings with extremely large neutron refractive index modulation". In McLeod, Robert R; Tomita, Yasuo; Sheridan, John T; Pascual Villalobos, Inmaculada (eds.). Photosensitive Materials and their Applications II. Vol. 12151. SPIE. pp. 70–76. Bibcode:2022SPIE12151E..09H. doi:10.1117/12.2623661. ISBN 978-1-5106-5178-4. S2CID 249056691.

- ^ a b c Byrne, James (2011). Neutrons, nuclei, and matter: an exploration of the physics of slow neutrons (Dover ed.). Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-486-48238-5.

- ^ Zijp WL, Nolthenius HJ, Baard JH, European Commission (1989). Nuclear data guide for reactor neutron metrology. Dordrecht: Kluwer. p. 359. ISBN 0-7923-0486-1. CD-NA-12-354-EN-C.

- ^ Watt, B. E. (15 September 1952). "Energy Spectrum of Neutrons from Thermal Fission of U235". Physical Review. 87 (6): 1037–1041. Bibcode:1952PhRv...87.1037W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.87.1037.

- ^ Kauffman, Andrew; Herminghuysen, Kevin; Van Zile, Matthew; White, Susan; Hatch, Joel; Maier, Andrew; Cao, Lei R. (October 2024). "Review of research and capabilities of 500 kW research reactor at the Ohio State University". Annals of Nuclear Energy. 206 110647. Bibcode:2024AnNuE.20610647K. doi:10.1016/j.anucene.2024.110647.

- ^ Freeman, Tami (May 23, 2008). "Facing up to secondary neutrons". Medical Physics Web. Archived from the original on 2010-12-20. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

- ^ Heilbronn, L.; Nakamura, T; Iwata, Y; Kurosawa, T; Iwase, H; Townsend, LW (2005). "Expand+Overview of secondary neutron production relevant to shielding in space". Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 116 (1–4): 140–143. doi:10.1093/rpd/nci033. PMID 16604615. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-25.

- ^ "Some Physics of Uranium. Accessed March 7, 2009". Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2009.