Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Breeder reactor

View on Wikipedia

A breeder reactor is a nuclear reactor that generates more fissile material than it consumes.[1] These reactors can be fueled with more-commonly available isotopes of uranium and thorium, such as uranium-238 and thorium-232, as opposed to the rare uranium-235 which is used in conventional reactors. These materials are called fertile materials since they can be bred into fuel by these breeder reactors.

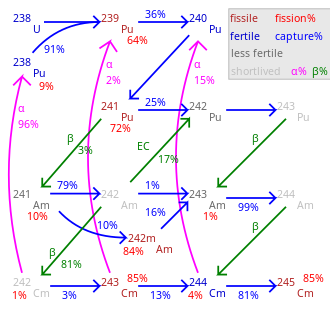

Breeder reactors achieve this because their neutron economy is high enough to create more fissile fuel than they use. These extra neutrons are absorbed by the fertile material that is loaded into the reactor along with fissile fuel. This irradiated fertile material in turn transmutes into fissile material which can undergo fission reactions.

Breeders were at first found attractive because they made more complete use of uranium fuel than light-water reactors, but interest declined after the 1960s as more uranium reserves were found[2] and new methods of uranium enrichment reduced fuel costs.

Types

[edit]

Many types of breeder reactor are possible:

A "breeder" is simply a nuclear reactor designed for very high neutron economy with an associated conversion rate higher than 1.0. In principle, almost any reactor design could be tweaked to become a breeder. For example, the light-water reactor, a heavily moderated thermal design, evolved into the RMWR concept, using light water in a low-density supercritical form to increase the neutron economy enough to allow breeding.

Aside from water-cooled, there are many other types of breeder reactor currently envisioned as possible. These include molten-salt cooled, gas cooled, and liquid-metal cooled designs in many variations. Almost any of these basic design types may be fueled by uranium, plutonium, many minor actinides, or thorium, and they may be designed for many different goals, such as creating more fissile fuel, long-term steady-state operation, or active burning of nuclear wastes.

Extant reactor designs are sometimes divided into two broad categories based upon their neutron spectrum, which generally separates those designed to use primarily uranium and transuranics from those designed to use thorium and avoid transuranics. These designs are:

- Fast breeder reactors (FBRs) which use 'fast' (i.e. unmoderated) neutrons to breed fissile plutonium (and possibly higher transuranics) from fertile uranium-238. The fast spectrum is flexible enough that it can also breed fissile uranium-233 from thorium, if desired.

- Thermal breeder reactors which use 'thermal-spectrum' or 'slow' (i.e. moderated) neutrons to breed fissile uranium-233 from thorium. Due to the behavior of the various nuclear fuels, a thermal breeder is thought commercially feasible only with thorium fuel, which avoids the buildup of the heavier transuranics.

Fast breeder reactor

[edit]

All current[when?] large-scale FBR power stations were liquid metal fast breeder reactors (LMFBR) cooled by liquid sodium. These have been of one of two designs:[1]: 43

- Loop type, in which the primary coolant is circulated through primary heat exchangers outside the reactor tank (but inside the biological shield due to radioactive 24Na in the primary coolant)

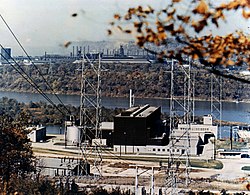

Experimental Breeder Reactor II, which served as the prototype for the Integral Fast Reactor - Pool type, in which the primary heat exchangers and pumps are immersed in the reactor tank

There are only two commercially operating breeder reactors as of 2017[update]: the BN-600 reactor, at 560 MWe, and the BN-800 reactor, at 880 MWe. Both are Russian sodium-cooled reactors. The designs use liquid metal as the primary coolant, to transfer heat from the core to steam used to power the electricity generating turbines. FBRs have been built cooled by liquid metals other than sodium—some early FBRs used mercury; other experimental reactors have used a sodium-potassium alloy. Both have the advantage that they are liquids at room temperature, which is convenient for experimental rigs but less important for pilot or full-scale power stations.

Three of the proposed generation IV reactor types are FBRs:[3]

- Gas-cooled fast reactor cooled by helium.

- Sodium-cooled fast reactor based on the existing LMFBR and integral fast reactor designs.

- Lead-cooled fast reactor based on Soviet naval propulsion units.

FBRs usually use a mixed oxide fuel core of up to 20% plutonium dioxide (PuO2) and at least 80% uranium dioxide (UO2). Another fuel option is metal alloys, typically a blend of uranium, plutonium, and zirconium (used because it is "transparent" to neutrons). Enriched uranium can be used on its own.

Many designs surround the reactor core in a blanket of tubes that contain non-fissile uranium-238, which, by capturing fast neutrons from the reaction in the core, converts to fissile plutonium-239 (as is some of the uranium in the core), which is then reprocessed and used as nuclear fuel. Other FBR designs rely on the geometry of the fuel (which also contains uranium-238), arranged to attain sufficient fast neutron capture. The plutonium-239 (or the fissile uranium-235) fissile cross-section is much smaller in a fast spectrum than in a thermal spectrum, as is the ratio between the 239Pu/235U fission cross-section and the 238U absorption cross-section. This increases the concentration of 239Pu/235U needed to sustain a chain reaction, as well as the ratio of breeding to fission.[4] On the other hand, a fast reactor needs no moderator to slow down the neutrons at all, taking advantage of the fast neutrons producing a greater number of neutrons per fission than slow neutrons. For this reason ordinary liquid water, being a moderator and neutron absorber, is an undesirable primary coolant for fast reactors. Because large amounts of water in the core are required to cool the reactor, the yield of neutrons and therefore breeding of 239Pu are strongly affected. Theoretical work has been done on reduced moderation water reactors, which may have a sufficiently fast spectrum to provide a breeding ratio slightly over 1. This would likely result in an unacceptable power derating and high costs in a liquid-water-cooled reactor, but the supercritical water coolant of the supercritical water reactor (SCWR) has sufficient heat capacity to allow adequate cooling with less water, making a fast-spectrum water-cooled reactor a practical possibility.[5]

The type of coolants, temperatures, and fast neutron spectrum puts the fuel cladding material (normally austenitic stainless or ferritic-martensitic steels) under extreme conditions. The understanding of the radiation damage, coolant interactions, stresses, and temperatures are necessary for the safe operation of any reactor core. All materials used to date in sodium-cooled fast reactors have known limits.[6] Oxide dispersion-strengthened alloy steel is viewed as the long-term radiation resistant fuel-cladding material that can overcome the shortcomings of today's material choices.

Integral fast reactor

[edit]One design of fast neutron reactor, specifically conceived to address the waste disposal and plutonium issues, was the integral fast reactor (IFR, also known as an integral fast breeder reactor, although the original reactor was designed to not breed a net surplus of fissile material).[7][8]

To solve the waste disposal problem, the IFR had an on-site electrowinning fuel-reprocessing unit that recycled the uranium and all the transuranics (not just plutonium) via electroplating, leaving just short-half-life fission products in the waste. Some of these fission products could later be separated for industrial or medical uses and the rest sent to a waste repository. The IFR pyroprocessing system uses molten cadmium cathodes and electrorefiners to reprocess metallic fuel directly on-site at the reactor.[9] Such systems co-mingle all the minor actinides with both uranium and plutonium. The systems are compact and self-contained, so that no plutonium-containing material needs to be transported away from the site of the breeder reactor. Breeder reactors incorporating such technology would most likely be designed with breeding ratios very close to 1.00, so that after an initial loading of enriched uranium and/or plutonium fuel, the reactor would then be refueled only with small deliveries of natural uranium. A quantity of natural uranium equivalent to a block about the size of a milk crate delivered once per month would be all the fuel such a 1 gigawatt reactor would need.[10] Such self-contained breeders are currently envisioned as the final self-contained and self-supporting ultimate goal of nuclear reactor designers.[11][4] The project was canceled in 1994 by United States Secretary of Energy Hazel O'Leary.[12][13]

Other fast reactors

[edit]

The first fast reactor built and operated was the Los Alamos Plutonium Fast Reactor ("Clementine") in Los Alamos, NM.[14] Clementine was fueled by Ga-stabilized delta-phase Pu and cooled with mercury. It contained a 'window' of Th-232 in anticipation of breeding experiments, but no reports were made available regarding this feature.

Another proposed fast reactor is a fast molten salt reactor, in which the molten salt's moderating properties are insignificant. This is typically achieved by replacing the light metal fluorides (e.g. LiF, BeF2) in the salt carrier with heavier metal chlorides (e.g., KCl, RbCl, ZrCl4).

Several prototype FBRs have been built, ranging in electrical output from a few light bulbs' equivalent (EBR-I, 1951) to over 1,000 MWe. As of 2006, the technology is not economically competitive to thermal reactor technology, but India, Japan, China, South Korea, and Russia are all committing substantial research funds to further development of fast breeder reactors, anticipating that rising uranium prices will change this in the long term. Germany, in contrast, abandoned the technology due to safety concerns. The SNR-300 fast breeder reactor was finished after 19 years despite cost overruns summing up to a total of €3.6 billion, only to then be abandoned.[15]

Thermal breeder reactor

[edit]

The advanced heavy-water reactor is one of the few proposed large-scale uses of thorium.[16] India is developing this technology, motivated by substantial thorium reserves; almost a third of the world's thorium reserves are in India, which lacks significant uranium reserves.

The third and final core of the Shippingport Atomic Power Station 60 MWe reactor was a light water thorium breeder, which began operating in 1977.[17] It used pellets made of thorium dioxide and uranium-233 oxide; initially, the U-233 content of the pellets was 5–6% in the seed region, 1.5–3% in the blanket region, and none in the reflector region. It operated at 236 MWt, generating 60 MWe, and ultimately produced over 2.1 billion kilowatt hours of electricity. After five years, the core was removed and found to contain nearly 1.4% more fissile material than when it was installed, demonstrating that breeding from thorium had occurred.[18][19]

A liquid fluoride thorium reactor is also planned as a thorium thermal breeder. Liquid-fluoride reactors may have attractive features, such as inherent safety, no need to manufacture fuel rods, and possibly simpler reprocessing of the liquid fuel. This concept was first investigated at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment in the 1960s. From 2012 it became the subject of renewed interest worldwide.[20]

Fuel resources

[edit]Breeder reactors could, in principle, extract almost all of the energy contained in uranium or thorium, decreasing fuel requirements by a factor of 100 compared to widely used once-through light water reactors, which extract less than 1% of the energy in the actinide metal (uranium or thorium) mined from the earth.[11] The high fuel-efficiency of breeder reactors could greatly reduce concerns about fuel supply, energy used in mining, and storage of radioactive waste. With seawater uranium extraction (currently too expensive to be economical), there is enough fuel for breeder reactors to satisfy the world's energy needs for 5 billion years at 1983's total energy consumption rate, thus making nuclear energy effectively a renewable energy.[21][22] In addition to seawater, the average crustal granite rocks contain significant quantities of uranium and thorium that with breeder reactors can supply abundant energy for the remaining lifespan of the sun on the main sequence of stellar evolution.[23]

Nuclear waste

[edit]| Actinides[24] by decay chain | Half-life range (a) |

Fission products of 235U by yield[25] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4n (Thorium) |

4n + 1 (Neptunium) |

4n + 2 (Radium) |

4n + 3 (Actinium) |

4.5–7% | 0.04–1.25% | <0.001% | ||

| 228Ra№ | 4–6 a | 155Euþ | ||||||

| 248Bk[26] | > 9 a | |||||||

| 244Cmƒ | 241Puƒ | 250Cf | 227Ac№ | 10–29 a | 90Sr | 85Kr | 113mCdþ | |

| 232Uƒ | 238Puƒ | 243Cmƒ | 29–97 a | 137Cs | 151Smþ | 121mSn | ||

| 249Cfƒ | 242mAmƒ | 141–351 a |

No fission products have a half-life | |||||

| 241Amƒ | 251Cfƒ[27] | 430–900 a | ||||||

| 226Ra№ | 247Bk | 1.3–1.6 ka | ||||||

| 240Pu | 229Th | 246Cmƒ | 243Amƒ | 4.7–7.4 ka | ||||

| 245Cmƒ | 250Cm | 8.3–8.5 ka | ||||||

| 239Puƒ | 24.1 ka | |||||||

| 230Th№ | 231Pa№ | 32–76 ka | ||||||

| 236Npƒ | 233Uƒ | 234U№ | 150–250 ka | 99Tc₡ | 126Sn | |||

| 248Cm | 242Pu | 327–375 ka | 79Se₡ | |||||

| 1.33 Ma | 135Cs₡ | |||||||

| 237Npƒ | 1.61–6.5 Ma | 93Zr | 107Pd | |||||

| 236U | 247Cmƒ | 15–24 Ma | 129I₡ | |||||

| 244Pu | 80 Ma |

... nor beyond 15.7 Ma[28] | ||||||

| 232Th№ | 238U№ | 235Uƒ№ | 0.7–14.1 Ga | |||||

| ||||||||

In broad terms, spent nuclear fuel has three main components. The first consists of fission products, the leftover fragments of fuel atoms after they have been split to release energy. Fission products come in dozens of elements and hundreds of isotopes, all of them lighter than uranium. The second main component of spent fuel is transuranics (atoms heavier than uranium), which are generated from uranium or heavier atoms in the fuel when they absorb neutrons but do not undergo fission. All transuranic isotopes fall within the actinide series on the periodic table, and so they are frequently referred to as the actinides. The largest component is the remaining uranium which is around 98.25% uranium-238, 1.1% uranium-235, and 0.65% uranium-236. The U-236 comes from the non-fission capture reaction where U-235 absorbs a neutron but releases only a high energy gamma ray instead of undergoing fission.

The physical behavior of the fission products is markedly different from that of the actinides. In particular, fission products do not undergo fission and therefore cannot be used as nuclear fuel. Indeed, because fission products are often neutron poisons (absorbing neutrons that could be used to sustain a chain reaction), fission products are viewed as nuclear 'ashes' left over from consuming fissile materials. Furthermore, only seven long-lived fission product isotopes have half-lives longer than a hundred years, which makes their geological storage or disposal less problematic than for transuranic materials.[29]

With increased concerns about nuclear waste, breeding fuel cycles came under renewed interest as they can reduce actinide wastes, particularly plutonium and minor actinides.[30] Breeder reactors are designed to fission the actinide wastes as fuel and thus convert them to more fission products. After spent nuclear fuel is removed from a light water reactor, it undergoes a complex decay profile as each nuclide decays at a different rate. There is a large gap in the decay half-lives of fission products compared to transuranic isotopes. If the transuranics are left in the spent fuel, after 1,000 to 100,000 years the slow decay of these transuranics would generate most of the radioactivity in that spent fuel. Thus, removing the transuranics from the waste eliminates much of the long-term radioactivity of spent nuclear fuel.[31]

Today's commercial light-water reactors do breed some new fissile material, mostly in the form of plutonium. Because commercial reactors were never designed as breeders, they do not convert enough uranium-238 into plutonium to replace the uranium-235 consumed. Nonetheless, at least one-third of the power produced by commercial nuclear reactors comes from fission of plutonium generated within the fuel.[32] Even with this level of plutonium consumption, light water reactors consume only part of the plutonium and minor actinides they produce, and nonfissile isotopes of plutonium build up, along with significant quantities of other minor actinides.[33]

Breeding fuel cycles attracted renewed interest because of their potential to reduce actinide wastes, particularly various isotopes of plutonium and the minor actinides (neptunium, americium, curium, etc.).[30] Since breeder reactors on a closed fuel cycle would use nearly all of the isotopes of these actinides fed into them as fuel, their fuel requirements would be reduced by a factor of about 100. The volume of waste they generate would be reduced by a factor of about 100 as well. While there is a huge reduction in the volume of waste from a breeder reactor, the activity of the waste is about the same as that produced by a light-water reactor.[34]

Waste from a breeder reactor has a different decay behavior because it is made up of different materials. Breeder reactor waste is mostly fission products, while light-water reactor waste is mostly unused uranium isotopes and a large quantity of transuranics. After spent nuclear fuel has been removed from a light-water reactor for longer than 100,000 years, the transuranics would be the main source of radioactivity. Eliminating them would eliminate much of the long-term radioactivity from the spent fuel.[31]

In principle, breeder fuel cycles can recycle and consume all actinides,[21] leaving only fission products. As the graphic in this section indicates, fission products have a peculiar "gap" in their aggregate half-lives, such that no fission products have a half-life between 91 and 200,000 years. As a result of this physical oddity, after several hundred years in storage, the activity of the radioactive waste from an FBR would quickly drop to the low level of the long-lived fission products. However, to obtain this benefit requires the highly efficient separation of transuranics from spent fuel. If the fuel reprocessing methods used leave a large fraction of the transuranics in the final waste stream, this advantage would be greatly reduced.[11]

The FBR's fast neutrons can fission actinide nuclei with even numbers of both protons and neutrons. Such nuclei usually lack the low-speed "thermal neutron" resonances of fissile fuels used in LWRs.[35] The thorium fuel cycle inherently produces lower levels of heavy actinides. The fertile material in the thorium fuel cycle has an atomic weight of 232, while the fertile material in the uranium fuel cycle has an atomic weight of 238. That mass difference means that thorium-232 requires six more neutron capture events per nucleus before the transuranic elements can be produced. In addition to this simple mass difference, the reactor gets two chances to fission the nuclei as the mass increases: First as the effective fuel nuclei U233, and as it absorbs two more neutrons, again as the fuel nuclei U235.[36][37]

A reactor whose main purpose is to destroy actinides rather than increasing fissile fuel-stocks is sometimes known as a burner reactor. Both breeding and burning depend on good neutron economy, and many designs can do either. Breeding designs surround the core by a breeding blanket of fertile material. Waste burners surround the core with non-fertile wastes to be destroyed. Some designs add neutron reflectors or absorbers.[4]

Design

[edit]| Isotope | Thermal fission cross section |

Thermal fission % |

Fast fission cross section |

Fast fission % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th-232 | 53.71 microbarn | 1 n | 79.94 millibarn | 3 n |

| U-232 | 76.52 barn | 59 | 2.063 barn | 95 |

| U-233 | 531.3 barn | 89 | 1.908 barn | 93 |

| U-235 | 585.1 barn | 81 | 1.218 barn | 80 |

| U-238 | 16.8 microbarn | 1 n | 306.4 millibarn | 11 |

| Np-237 | 20.19 millibarn | 3 n | 1.336 barn | 27 |

| Pu-238 | 17.77 barn | 7 | 1.968 barn | 70 |

| Pu-239 | 747.4 barn | 63 | 1.802 barn | 85 |

| Pu-240 | 36.21 millibarn | 1 n | 1.328 barn | 55 |

| Pu-241 | 1012 barn | 75 | 1.626 barn | 87 |

| Pu-242 | 2.436 millibarn | 1 n | 1.151 barn | 53 |

| Am-241 | 3.122 barn | 1 n | 1.395 barn | 21 |

| Am-242m | 6401 barn | 75 | 1.834 barn | 94 |

| Am-243 | 81.58 millibarn | 1 n | 1.081 barn | 23 |

| Cm-242 | 4.665 barn | 1 n | 1.775 barn | 10 |

| Cm-243 | 587.4 barn | 78 | 2.432 barn | 94 |

| Cm-244 | 1.022 barn | 4 n | 1.733 barn | 33 |

| n=non-fissile | ||||

Conversion ratio

[edit]One measure of a reactor's performance is the "conversion ratio", defined as the ratio of new fissile atoms produced to fissile atoms consumed. All proposed nuclear reactors except specially designed and operated actinide burners[4] experience some degree of conversion. As long as there is any amount of a fertile material within the neutron flux of the reactor, some new fissile material is always created. When the conversion ratio is greater than 1, it is often called the "breeding ratio".

For example, commonly used light water reactors have a conversion ratio of approximately 0.6. Pressurized heavy-water reactors running on natural uranium have a conversion ratio of 0.8.[40] In a breeder reactor, the conversion ratio is higher than 1. "Break-even" is achieved when the conversion ratio reaches 1.0 and the reactor produces as much fissile material as it uses.

Doubling time

[edit]The doubling time is the amount of time it would take for a breeder reactor to produce enough new fissile material to replace the original fuel and additionally produce an equivalent amount of fuel for another nuclear reactor. This was considered an important measure of breeder performance in early years, when uranium was thought to be scarce. However, since uranium is more abundant than thought in the early days of nuclear reactor development, and given the amount of plutonium available in spent reactor fuel, doubling time has become a less important metric in modern breeder-reactor design.[41][42]

Burnup

[edit]"Burnup" is a measure of how much energy has been extracted from a given mass of heavy metal in fuel, often expressed (for power reactors) in terms of gigawatt-days per ton of heavy metal. Burnup is an important factor in determining the types and abundances of isotopes produced by a fission reactor. Breeder reactors by design have high burnup compared to a conventional reactor, as breeder reactors produce more of their waste in the form of fission products, while most or all of the actinides are meant to be fissioned and destroyed.[43]

In the past, breeder-reactor development focused on reactors with low breeding ratios, from 1.01 for the Shippingport Reactor[44][45] running on thorium fuel and cooled by conventional light water to over 1.2 for the Soviet BN-350 liquid-metal-cooled reactor.[46] Theoretical models of breeders with liquid sodium coolant flowing through tubes inside fuel elements ("tube-in-shell" construction) suggest breeding ratios of at least 1.8 are possible on an industrial scale.[47] The Soviet BR-1 test reactor achieved a breeding ratio of 2.5 under non-commercial conditions.[48]

Reprocessing

[edit]Fission of the nuclear fuel in any reactor unavoidably produces neutron-absorbing fission products. The fertile material from a breeder reactor then needs to be reprocessed to remove those neutron poisons. This step is required to fully utilize the ability to breed as much or more fuel than is consumed. All reprocessing can present a proliferation concern, since it can extract weapons-usable material from spent fuel.[49] The most common reprocessing technique, PUREX, presents a particular concern since it was expressly designed to separate plutonium. Early proposals for the breeder-reactor fuel cycle posed an even greater proliferation concern because they would use PUREX to separate plutonium in a highly attractive isotopic form for use in nuclear weapons.[50][51]

Several countries are developing reprocessing methods that do not separate the plutonium from the other actinides. For instance, the non-water-based pyrometallurgical electrowinning process, when used to reprocess fuel from an integral fast reactor, leaves large amounts of radioactive actinides in the reactor fuel.[11] More conventional water-based reprocessing systems include SANEX, UNEX, DIAMEX, COEX, and TRUEX, and proposals to combine PUREX with those and other co-processes. All these systems have moderately better proliferation resistance than PUREX, though their adoption rate is low.[52][53][54]

In the thorium cycle, thorium-232 breeds by converting first to protactinium-233, which then decays to uranium-233. If the protactinium remains in the reactor, small amounts of uranium-232 are also produced, which has the strong gamma emitter thallium-208 in its decay chain. Similar to uranium-fueled designs, the longer the fuel and fertile material remain in the reactor, the more of these undesirable elements build up. In the envisioned commercial thorium reactors, high levels of uranium-232 would be allowed to accumulate, leading to extremely high gamma-radiation doses from any uranium derived from thorium. These gamma rays complicate the safe handling of a weapon and the design of its electronics; this explains why uranium-233 has never been pursued for weapons beyond proof-of-concept demonstrations.[55]

While the thorium cycle may be proliferation-resistant with regard to uranium-233 extraction from fuel (because of the presence of uranium-232), it poses a proliferation risk from an alternate route of uranium-233 extraction, which involves chemically extracting protactinium-233 and allowing it to decay to pure uranium-233 outside of the reactor. This process is an obvious chemical operation which is not required for normal operation of these reactor designs, but it could feasibly happen beyond the oversight of organizations such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and thus must be safeguarded against.[56]

Production

[edit]Like many aspects of nuclear power, fast breeder reactors have been subject to much controversy over the years. In 2010 the International Panel on Fissile Materials said "After six decades and the expenditure of the equivalent of tens of billions of dollars, the promise of breeder reactors remains largely unfulfilled and efforts to commercialize them have been steadily cut back in most countries". In Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States, breeder reactor development programs have been abandoned.[57][58] The rationale for pursuing breeder reactors—sometimes explicit and sometimes implicit—was based on the following key assumptions:[58][59]

- It was expected that uranium would be scarce and high-grade deposits would quickly become depleted if fission power were deployed on a large scale; the reality, however, is that since the end of the Cold War, uranium has been much cheaper and more abundant than early designers expected.[60]

- It was expected that breeder reactors would quickly become economically competitive with the light-water reactors that dominate nuclear power today, but the reality is that capital costs are at least 25% more than water-cooled reactors.

- It was thought that breeder reactors could be as safe and reliable as light-water reactors, but safety issues are cited as a concern with fast reactors that use a sodium coolant, where a leak could lead to a sodium fire.

- It was expected that the proliferation risks posed by breeders and their "closed" fuel cycle, in which plutonium would be recycled, could be managed. But since plutonium-breeding reactors produce plutonium from U238, and thorium reactors produce fissile U233 from thorium, all breeding cycles could theoretically pose proliferation risks.[61] However U-232, which is always present in U-233 produced in breeder reactors, is a strong gamma-emitter via its daughter products, and would make weapon handling extremely hazardous and the weapon easy to detect.[62]

Some past anti-nuclear advocates have become pro-nuclear power as a clean source of electricity since breeder reactors effectively recycle most of their waste. This solves one of the most-important negative issues of nuclear power. In the documentary Pandora's Promise, a case is made for breeder reactors because they provide a real high-kW alternative to fossil fuel energy. According to the movie, one pound of uranium provides as much energy as 5,000 barrels of oil.[63]

Notable reactors

[edit]| Reactor | Country when built |

Started | Shut down | Design MWe |

Final MWe |

Thermal Power MWt |

Capacity factor |

Number of coolant leaks |

Neutron temperature |

Coolant | Reactor class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFR | UK | 1962 | 1977 | 14 | 11 | 65 | 34% | 7 | Fast | NaK | Test |

| China Experimental Fast Reactor | China | 2012 | operating | 20 | 22 | 65 | 40% | 8 | Fast | Sodium | Test[68] |

| CFR-600 | China | 2017 | commissioning/2023 | 642 | 682 | 1882 | 34% | 27 | Fast | Sodium | Commercial[69] |

| BN-350 | Soviet Union | 1973 | 1999 | 350 | 52 | 750 | 43% | 15 | Fast | Sodium | Prototype |

| Rapsodie | France | 1967 | 1983 | 0 | – | 40 | – | 2 | Fast | Sodium | Test |

| Phénix | France | 1975 | 2010 | 233 | 130 | 563 | 40.5% | 31 | Fast | Sodium | Prototype |

| PFR | UK | 1976 | 1994 | 234 | 234 | 650 | 26.9% | 20 | Fast | Sodium | Prototype |

| KNK II | Germany | 1977 | 1991 | 18 | 17 | 58 | 17.1% | 21 | Fast | Sodium | Research/Test |

| SNR-300 | Germany | 1985 | 1991 | 327 | – | – | non-nuclear tests only | – | Fast | Sodium | Prototype/Commercial |

| BN-600 | Soviet Union | 1981 | operating | 560 | 560 | 1470 | 74.2% | 27 | Fast | Sodium | Prototype/Commercial (Gen2) |

| FFTF | US | 1982 | 1993 | 0 | – | 400 | – | 1 | Fast | Sodium | Test |

| Superphénix | France | 1985 | 1998 | 1200 | 1200 | 3000 | 7.9% | 7 | Fast | Sodium | Prototype/Commercial (Gen2) |

| FBTR | India | 1985 | operating | 13 | – | 40 | – | 6 | Fast | Sodium | Test |

| PFBR | India | 2004 | 2024 | 500 | – | 1250 | – | – | Fast | Sodium | Prototype/Commercial (Gen3) |

| Jōyō | Japan | 1977 | 2007 | 0 | – | 150 | – | – | Fast | Sodium | Test |

| Monju | Japan | 1995 | 2017 | 246 | 246 | 714 | trial only | 1 | Fast | Sodium | Prototype |

| BN-800 | Russia | 2015 | operating | 789 | 880 | 2100 | 73.4% | – | Fast | Sodium | Prototype/Commercial (Gen3) |

| MSRE | US | 1965 | 1969 | 0 | – | 7.4 | – | – | Epithermal | Molten salt (FLiBe) | Test |

| Clementine | US | 1946 | 1952 | 0 | – | 0.025 | – | – | Fast | Mercury | World's First Fast Reactor[14] |

| EBR-1 | US | 1951 | 1964 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.4 | – | – | Fast | NaK | First Power Reactor |

| Fermi-1 | US | 1963 | 1972 | 66 | 66 | 200 | – | – | Fast | Sodium | Prototype |

| EBR-2 | US | 1964 | 1994 | 19 | 19 | 62.5 | – | – | Fast | Sodium | Experimental/Test |

| Shippingport | US | 1977 as breeder |

1982 | 60 | 60 | 236 | – | – | Thermal | Light Water | Experimental-Core3 |

The Soviet Union constructed a series of fast reactors, the first being mercury-cooled and fueled with plutonium metal, and the later plants sodium-cooled and fueled with plutonium oxide. BR-1 (1955) was 100W (thermal) was followed by BR-2 at 100 kW and then the 5 MW BR-5.[48] BOR-60 (first criticality 1969) was 60 MW, with construction started in 1965.[70]

Future plants

[edit]

India

[edit]India has been trying to develop fast breeder reactors for decades but suffered repeated delays.[71] By December 2024 the Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor is due to be completed and commissioned.[72][73][74] The program is intended to use fertile thorium-232 to breed fissile uranium-233. India is also pursuing thorium thermal breeder reactor technology. India's focus on thorium is due to the nation's large reserves, though known worldwide reserves of thorium are four times those of uranium. India's Department of Atomic Energy said in 2007 that it would simultaneously construct four more breeder reactors of 500 MWe each including two at Kalpakkam.[75][needs update]

BHAVINI, an Indian nuclear power company, was established in 2003 to construct, commission, and operate all stage II fast breeder reactors outlined in India's three-stage nuclear power programme. To advance these plans, the FBR-600 is a pool-type sodium-cooled reactor with a rating of 600 MWe.[76][77][74]

China

[edit]The China Experimental Fast Reactor is a 25 MW(e) prototype for the planned China Prototype Fast Reactor.[78] It started generating power in 2011.[79] China initiated a research and development project in thorium molten-salt thermal breeder-reactor technology (liquid fluoride thorium reactor), formally announced at the Chinese Academy of Sciences annual conference in 2011. Its ultimate target was to investigate and develop a thorium-based molten salt nuclear system over about 20 years.[80][81][needs update]

South Korea

[edit]South Korea is developing a design for a standardized modular FBR for export, to complement the standardized pressurized water reactor and CANDU designs they have already developed and built, but has not yet committed to building a prototype.

Russia

[edit]Russia has a plan for increasing its fleet of fast breeder reactors significantly. A BN-800 reactor (800 MWe) at Beloyarsk was completed in 2012, succeeding a smaller BN-600.[82] It reached its full power production in 2016.[83] Plans for the construction of a larger BN-1200 reactor (1,200 MWe) was scheduled for completion in 2018, with two additional BN-1200 reactors built by the end of 2030.[84] However, in 2015 Rosenergoatom postponed construction indefinitely to allow fuel design to be improved after more experience of operating the BN-800 reactor, and among cost concerns.[85]

An experimental lead-cooled fast reactor, BREST-300 will be built at the Siberian Chemical Combine in Seversk. The BREST (Russian: bystry reaktor so svintsovym teplonositelem, English: fast reactor with lead coolant) design is seen as a successor to the BN series and the 300 MWe unit at the SCC could be the forerunner to a 1,200 MWe version for wide deployment as a commercial power generation unit. The development program is as part of an Advanced Nuclear Technologies Federal Program 2010–2020 that seeks to exploit fast reactors for uranium efficiency while 'burning' radioactive substances that would otherwise be disposed of as waste. Its core would measure about 2.3 metres in diameter by 1.1 metres in height and contain 16 tonnes of fuel. The unit would be refuelled every year, with each fuel element spending five years in total within the core. Lead coolant temperature would be around 540 °C, giving a high efficiency of 43%, primary heat production of 700 MWt yielding electrical power of 300 MWe. The operational lifespan of the unit could be 60 years. The design was expected to be completed by NIKIET in 2014 for construction between 2016 and 2020.[86] By the end of 2024 the cooling tower had been built, and the target for starting operation was 2026.[citation needed]

Japan

[edit]In 2006 the United States, France, and Japan signed an "arrangement" to research and develop sodium-cooled fast reactors in support of the Global Nuclear Energy Partnership.[87] In 2007 the Japanese government selected Mitsubishi Heavy Industries as the "core company in FBR development in Japan". Shortly thereafter, Mitsubishi FBR Systems was launched to develop and eventually sell FBR technology.[88]

France

[edit]In 2010 the French government allocated €651.6 million to the Commissariat à l'énergie atomique to finalize the design of ASTRID (Advanced Sodium Technological Reactor for Industrial Demonstration), a 600 MW fourth-generation reactor design to be finalized in 2020.[89][90] As of 2013[update] the UK had shown interest in the PRISM reactor and was working in concert with France to develop ASTRID. In 2019, CEA announced this design would not be built before mid-century.[91]

United States

[edit]Kirk Sorensen, former NASA scientist and chief nuclear technologist at Teledyne Brown Engineering, has long been a promoter of thorium fuel cycle and particularly liquid fluoride thorium reactors. In 2011, Sorensen founded Flibe Energy, a company aimed to develop 20–50 MW LFTR reactor designs to power military bases.[92][93][94][95]

In October 2010 GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy signed a memorandum of understanding with the operators of the US Department of Energy's Savannah River Site, which should allow the construction of a demonstration plant based on the company's S-PRISM fast breeder reactor prior to the design receiving full Nuclear Regulatory Commission licensing approval.[96] In October 2011 The Independent reported that the UK Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) and senior advisers within the Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC) had asked for technical and financial details of PRISM, partly as a means of reducing the country's plutonium stockpile.[97]

The traveling wave reactor proposed in a patent by Intellectual Ventures is a fast breeder reactor designed to not need fuel reprocessing during the decades-long lifetime of the reactor. The breed-burn wave in the TWR design does not move from one end of the reactor to the other but gradually from the inside out. Moreover, as the fuel's composition changes through nuclear transmutation, fuel rods are continually reshuffled within the core to optimize the neutron flux and fuel usage at any given point in time. Thus, instead of letting the wave propagate through the fuel, the fuel itself is moved through a largely stationary burn wave. This is contrary to many media reports, which have popularized the concept as a candle-like reactor with a burn region that moves down a stick of fuel. By replacing a static core configuration with an actively managed "standing wave" or "soliton" core, TerraPower's design avoids the problem of cooling a highly variable burn region. Under this scenario, the reconfiguration of fuel rods is accomplished remotely by robotic devices; the containment vessel remains closed during the procedure, and there is no associated downtime.[98]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Waltar AE, Reynolds AB (1981). Fast breeder reactors. New York: Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-025983-3. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ Helmreich, J. E. Gathering Rare Ores: The Diplomacy of Uranium Acquisition, 1943–1954, Princeton UP, 1986: ch. 10 ISBN 0-7837-9349-9.

- ^ "A Technology Roadmap for Generation IV Nuclear Energy Systems" (PDF). Generation IV International Forum. December 2002. GIF-002-00. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d E. A. Hoffman; W. S. Yang; R. N. Hill. "Preliminary Core Design Studies for the Advanced Burner Reactor over a Wide Range of Conversion Ratios" (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. ANL-AFCI-177.

- ^ T. Nakatsuka; et al. Current Status of Research and Development of Supercritical Water-Cooled Fast Reactor (Super Fast Reactor) in Japan. Presented at IAEA Technical Committee Meeting on SCWRs in Pisa, 5–8 July 2010.

- ^ Davis, Thomas P. (2018). "Review of the iron-based materials applicable for the fuel and core of future Sodium Fast Reactors (SFR)" (PDF). Office for Nuclear Regulation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "The Integral Fast Reactor". Reactors Designed by Argonne National Laboratory. Argonne National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ "National Policy Analysis #378: Integral Fast Reactors: Source of Safe, Abundant, Non-Polluting Power – December 2001". Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ Hannum, W.H., Marsh, G.E., and Stanford, G.S. (2004). PUREX and PYRO are not the same Archived 23 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Physics and Society, July 2004.

- ^ University of Washington (2004). Energy Numbers: Energy in natural processes and human consumption, some numbers Archived 15 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Pyroprocessing Technologies: Recycling Used Nuclear Fuel For A Sustainable Energy Future" (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2013.

- ^ Kirsch, Steve. "The Integral Fast Reactor (IFR) project: Congress Q&A". Archived from the original on 16 December 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ Stanford, George S. "Comments on the Misguided Termination of the IFR Project" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Patenaude, Hannah K.; Freibert, Franz J. (3 July 2023). "Oh, My Darling Clementine: A Detailed History and Data Repository of the Los Alamos Plutonium Fast Reactor". Nuclear Technology. 209 (7): 963–1007. Bibcode:2023NucTe.209..963P. doi:10.1080/00295450.2023.2176686. ISSN 0029-5450.

- ^ Werner Meyer-Larsen: Der Koloß von Kalkar. Der Spiegel 43/1981 vom 19 October 1981, S. 42–55. [["Der Koloß von Kalkar", Der Spiegel, 13 September]] (German)

- ^ "Thorium". Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ "Shippingport Atomic Power Station: A National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2007.

- ^ Adams, Rod (1 October 1995). "Light Water Breeder Reactor: Adapting A Proven System". Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ Thorium Archived 19 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine information from the World Nuclear Association

- ^ Stenger, Victor (12 January 2012). "LFTR: A Long-Term Energy Solution?". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ a b Cohen, Bernard L. "Breeder reactors: A renewable energy source" (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ Weinberg, A. M., and R. P. Hammond (1970). "Limits to the use of energy," Am. Sci. 58, 412.

- ^ "There's Atomic Energy in Granite". 8 February 2013.

- ^ Plus radium (element 88). While actually a sub-actinide, it immediately precedes actinium (89) and follows a three-element gap of instability after polonium (84) where no nuclides have half-lives of at least four years (the longest-lived nuclide in the gap is radon-222 with a half life of less than four days). Radium's longest lived isotope, at 1,600 years, thus merits the element's inclusion here.

- ^ Specifically from thermal neutron fission of uranium-235, e.g. in a typical nuclear reactor.

- ^ Milsted, J.; Friedman, A. M.; Stevens, C. M. (1965). "The alpha half-life of berkelium-247; a new long-lived isomer of berkelium-248". Nuclear Physics. 71 (2): 299. Bibcode:1965NucPh..71..299M. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(65)90719-4.

"The isotopic analyses disclosed a species of mass 248 in constant abundance in three samples analysed over a period of about 10 months. This was ascribed to an isomer of Bk248 with a half-life greater than 9 [years]. No growth of Cf248 was detected, and a lower limit for the β− half-life can be set at about 104 [years]. No alpha activity attributable to the new isomer has been detected; the alpha half-life is probably greater than 300 [years]." - ^ This is the heaviest nuclide with a half-life of at least four years before the "sea of instability".

- ^ Excluding those "classically stable" nuclides with half-lives significantly in excess of 232Th; e.g., while 113mCd has a half-life of only fourteen years, that of 113Cd is eight quadrillion years.

- ^ "Radioactive Waste Management". World Nuclear Association. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Supply of Uranium". World Nuclear Association. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ a b Bodansky, David (January 2006). "The Status of Nuclear Waste Disposal". Physics and Society. 35 (1). American Physical Society. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Information Paper 15". World Nuclear Association. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ U. Mertyurek; M. W. Francis; I. C. Gauld. "SCALE 5 Analysis of BWR Spent Nuclear Fuel Isotopic Compositions for Safety Studies" (PDF). ORNL/TM-2010/286. OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ "Fast Breeder Reactors" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Neutron Cross Sections4.7.2". National Physical Laboratory. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ David, Sylvain; Elisabeth Huffer; Hervé Nifenecker. "Revisiting the thorium-uranium nuclear fuel cycle" (PDF). europhysicsnews. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ "Fissionable Isotopes". Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ "Plentiful Energy: The Story of the Integral Fast Reactor" (PDF). p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ "Cross Section Table".

- ^ Kadak, Prof. Andrew C. "Lecture 4, Fuel Depletion & Related Effects". Operational Reactor Safety 22.091/22.903. Hemisphere, as referenced by MIT. p. Table 6–1, "Average Conversion or Breeding Ratios for Reference Reactor Systems". Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ Rodriguez, Placid; Lee, S. M. "Who is afraid of breeders?". Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research, Kalpakkam 603 102, India. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ R. Prasad (10 October 2002). "Fast breeder reactor: Is advanced fuel necessary?". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 5 December 2003.

- ^ "Fast Reactor Systems and Innovative Fuels for Minor Actinides Homogeneous Recycling" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2016.

- ^ Adams, R. (1995). Light Water Breeder Reactor (Archived 15 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine), Atomic Energy Insights 1.

- ^ Kasten, P. R. (1998) Review of the Radkowsky Thorium Reactor Concept (Archived 25 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine). Science & Global Security 7, 237–269.

- ^ Fast Breeder Reactors (Archived 11 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine), Department of Physics & Astronomy, Georgia State University. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- ^ Hiraoka, T., Sako, K., Takano, H., Ishii, T., and Sato, M. (1991). A high-breeding fast reactor with fission product gas purge/tube-in-shell metallic fuel assemblies (Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine). Nuclear Technology 93, 305–329.

- ^ a b Valerii Korobeinikov (31 March – 2 April 2014). Innovative Concepts Based on Fast Reactor Technology (PDF). 1st Consultancy Meeting for Review of Innovative Reactor Concepts for Prevention of Severe Accidents and Mitigation of their Consequences. International Atomic Energy Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ R. Bari; et al. (2009). "Proliferation Risk Reduction Study ofAlternative Spent Fuel Processing" (PDF). BNL-90264-2009-CP. Brookhaven National Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ C.G. Bathke; et al. (2008). "An Assessment of the Proliferation Resistance of Materials in Advanced Fuel Cycles" (PDF). Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ "An Assessment of the Proliferation Resistance of Materials in Advanced Nuclear Fuel Cycles" (PDF). 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ Ozawa, M.; Sano, Y.; Nomura, K.; Koma, Y.; Takanashi, M. "A New Reprocessing System Composed of PUREX and TRUEX Processes For Total Separation of Long-lived Radionuclides" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ Simpson, Michael F.; Law, Jack D. (February 2010). "Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing" (PDF). Idaho National Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "Proliferation Risk Reduction Study of Alternative Spent Fuel Processing" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ Kang and Von Hippel (2001). "U-232 and the Proliferation-Resistance of U-233 in Spent Fuel" (PDF). 0892-9882/01. Science & Global Security, Volume 9 pp 1–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Thorium: Proliferation warnings on nuclear 'wonder-fuel'". 2012. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ M.V. Ramana; Mycle Schneider (May–June 2010). "It's time to give up on breeder reactors" (PDF). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b Frank von Hippel; et al. (February 2010). Fast Breeder Reactor Programs: History and Status (PDF). International Panel on Fissile Materials. ISBN 978-0-9819275-6-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ M.V. Ramana; Mycle Schneider (May–June 2010). "It's time to give up on breeder reactors" (PDF). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ "Global Uranium Supply and Demand – Council on Foreign Relations". Archived from the original on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Global Uranium Supply and Demand – Council on Foreign Relations". Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Introduction to Weapons of Mass Destruction, Langford, R. Everett (2004). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 85. ISBN 0-471-46560-7. "The US tested a few uranium-233 bombs, but the presence of uranium-232 in the uranium-233 was a problem; the uranium-232 is a copious alpha emitter and tended to 'poison' the uranium-233 bomb by knocking stray neutrons from impurities in the bomb material, leading to possible pre-detonation. Separation of the uranium-232 from the uranium-233 proved to be very difficult and not practical. The uranium-233 bomb was never deployed since plutonium-239 was becoming plentiful."

- ^ Len Koch, pioneering nuclear engineer (2013). Pandora's Promise (Motion picture). Impact Partners and CNN Films. 11 minutes in. Archived from the original (DVD, streaming) on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

One pound of uranium, which is the size of my fingertip, if you could release all of the energy, has the equivalent of about 5,000 barrels of oil.

- ^ "Nuclear Fusion: WNA - World Nuclear Association". Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ S. R. Pillai, M. V. Ramana (2014). "Breeder reactors: A possible connection between metal corrosion and sodium leaks". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 70 (3): 49–55. Bibcode:2014BuAtS..70c..49P. doi:10.1177/0096340214531178. S2CID 144406710. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Database on Nuclear Power Reactors". PRIS. IAEA. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Experimental Breeder Reactor 1 (EBR-1) - Cheeka Tales". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ "Chinese fast reactor begins high-power operation: New Nuclear - World Nuclear News".

- ^ "China's New Breeder Reactors May Produce More Than Just Watts - IEEE Spectrum".

- ^ FSUE "State Scientific Center of Russian Federation Research Institute of Atomic Reactors". "Experimental fast reactor BOR-60". Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "India's First Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor Has a New Deadline. Should We Trust It? – the Wire Science". 20 August 2020.

- ^ Srikanth (27 November 2011). "80% of work on fast breeder reactor at Kalpakkam over". The Hindu. Kalpakkam. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Jaganathan, Venkatachari (11 May 2011). "India's new fast-breeder on track, nuclear power from September next". Hindustan Times. Chennai. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ a b "India's first Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor in final stages of commissioning". The New Indian Express. 30 October 2020. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Home – India Defence". Archived from the original on 24 November 2011.

- ^ Conceptual Design of PFBR Core S.M. Lee, S Govindarajan, R. Indira, T.M. John, P. Mohanakrishnan, R. Shankar Singh, S B. Bhoje Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research (IGCAR), Kalpakkam, India https://inis.iaea.org/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/28/014/28014318.pdf Archived 20 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "FBR-600 - India's Next-gen Commercial Fast Breeder Reactor [CFBR]". Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "IAEA Fast Reactor Database" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "China's experimental fast neutron reactor begins generating power". xinhuanet. July 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Qimin, Xu (26 January 2011). "The future of nuclear power plant safety "are not picky eaters"" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

Yesterday, as the Chinese Academy of Sciences of the first to start one of the strategic leader in science and technology projects, "the future of advanced nuclear fission energy – nuclear energy, thorium-based molten salt reactor system" project was officially launched. The scientific goal is 20 years or so, developed a new generation of nuclear energy systems, all the technical level reached in the test and have all the intellectual property rights.

- ^ Clark, Duncan (16 February 2011). "China enters race to develop nuclear energy from thorium". Environment Blog. London: The Guardian (UK). Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "Белоярская АЭС: начался выход БН-800 на минимальный уровень мощности". AtomInfo.ru. Archived from the original on 30 June 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "Russian fast reactor reaches full power". Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ "До 2030 в России намечено строительство трёх энергоблоков с реакторами БН-1200". AtomInfo.ru. Archived from the original on 5 August 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "Russia postpones BN-1200 in order to improve fuel design". World Nuclear News. 16 April 2015. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Fast moves for nuclear development in Siberia". World Nuclear Association. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ "Department of Energy – Generation IV International Forum Signs Agreement to Collaborate on Sodium Cooled Fast Reactors". Archived from the original on 20 April 2008.

- ^ "MHI launches fast breeder group". Nuclear Engineering International. 2 July 2007. Archived from the original on 28 July 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ World Nuclear News (16 September 2010). "French government puts up funds for Astrid". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Quatrième génération: vers un nucléaire durable" (PDF) (in French). CEA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "France drops plans to build sodium-cooled nuclear reactor". Reuters. 30 August 2019. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ "Flibe Energy". Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ "Kirk Sorensen has started a Thorium Power company Flibe Energy". The Next Bi Future. 23 May 2011. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "Live chat: nuclear thorium technologist Kirk Sorensen". Environment Blog. London: The Guardian (UK). 7 September 2001. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Martin, William T. (27 September 2011). "New Huntsville company to build thorium-based nuclear reactors". Huntsville Newswire. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "Prototype Prism proposed for Savannah River". World Nuclear News. 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Connor, Steve (28 October 2011). "New life for old idea that could dissolve our nuclear waste". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 29 October 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "TR10: Traveling Wave Reactor". Technology Review. March 2009. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

External links

[edit]- Information Digest, 2022–2023 (NUREG-1350, Volume 34), NRC

- Reactors Designed by Argonne National Laboratory: Fast Reactor Technology Argonne pioneered the development of fast reactors and is a leader in the development of fast reactors worldwide. See also Argonne's Nuclear Science and Technology Legacy.

- The Changing Need for a Breeder Reactor by Richard Wilson at The Uranium Institute 24th Annual Symposium, September 1999

- Experimental Breeder Reactor-II (EBR-II): An Integrated Experimental Fast Reactor Nuclear Power Station

- International Thorium Energy Organisation – www.IThEO.org

- A Path Forward for the LMFBR

- Plutonium Fuel Fabrication by Argonne National Laboratory on YouTube

Breeder reactor

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Principles

Breeding Mechanism

In breeder reactors, the breeding mechanism entails the neutron-induced transmutation of fertile isotopes—non-fissile nuclides such as uranium-238 (U-238) or thorium-232 (Th-232)—into fissile isotopes capable of sustaining fission chain reactions, such as plutonium-239 (Pu-239) or uranium-233 (U-233). This occurs through neutron capture followed by beta-minus decays: for the uranium-plutonium cycle, U-238 absorbs a neutron to form U-239, which decays (half-life 23.5 minutes) to neptunium-239 (Np-239) and then to Pu-239 (half-life 2.36 days); similarly, Th-232 captures a neutron to yield protactinium-233 (Pa-233, half-life 27 days) before becoming U-233.[7][8] The process leverages excess neutrons from fission events, where each fission typically releases 2.4–2.9 neutrons on average, allowing some to propagate the chain reaction while others drive breeding.[7] The breeding ratio, defined as the ratio of fissile atoms produced to fissile atoms consumed (primarily via fission or parasitic capture), must exceed unity for net fissile gain; values above 1.1–1.2 are targeted in designs to account for reprocessing losses and ensure sustainability.[9] Neutron economy is central: the average neutrons emitted per absorption in fissile material (η) must surpass 2 to support both criticality and breeding after accounting for leakage, structural captures, and fission product buildup.[7] In fast-spectrum breeders, high-energy neutrons minimize parasitic absorption in coolant or cladding while enhancing η for Pu-239 (≈2.9 for fast neutrons versus ≈2.1 for thermal), enabling efficient U-238 utilization—over 60 times more energy extractable from natural uranium compared to once-through light-water cycles.[10][11] Thermal-spectrum breeding, as in thorium-fueled designs, relies on moderated neutrons but requires precise fuel blanketing to achieve ratios near 1, historically limited by higher parasitic captures; experimental evidence from the Shippingport Light Water Breeder Reactor (1977–1982) demonstrated a seed-blanket core yielding a conversion ratio of 1.07 using Th-232 and U-233.[7] Overall, breeding extends fuel resources by converting the 99.3% abundant U-238 in natural uranium, but demands advanced fuels, reprocessing, and safeguards against proliferation risks from separated Pu-239.[8][10]Neutron Economy and Reactor Physics

In breeder reactors, neutron economy refers to the balance between neutrons produced via fission and those consumed or lost, which must exceed requirements for criticality to enable net fissile material production. Fission of isotopes like plutonium-239 yields approximately 2.9 neutrons per event in a fast spectrum, providing the surplus needed for both sustaining the chain reaction (requiring one neutron per fission for k_eff ≈ 1) and breeding via capture in fertile materials such as uranium-238. Parasitic losses from leakage, structural absorption, and coolant interactions must be minimized to achieve a breeding ratio greater than unity, where fissile atoms produced exceed those consumed.[12] The fast neutron spectrum, typically with energies above 1 MeV and lacking a moderator, enhances neutron economy by reducing non-fissile captures and increasing the probability of fission over absorption (lower alpha, the capture-to-fission ratio). For plutonium-239, the reproduction factor eta—neutrons produced per absorption in the fuel—reaches about 2.1 to 2.3 in fast conditions, compared to lower values in thermal spectra due to higher resonance captures. This efficiency allows excess neutrons to transmute fertile isotopes: a fast neutron captured by U-238 forms U-239, which beta-decays to neptunium-239 and then plutonium-239, with the process optimized in a surrounding blanket region. In contrast, thermal spectra suffer poorer economy from moderator absorptions and softer neutron energies that favor capture without fission in actinides.[12][13] Reactor physics in breeders hinges on achieving k_eff > 1 while maximizing the breeding gain, often quantified as BR = (fissile produced / fissile destroyed), targeting values of 1.05 to 1.3 in operational designs. The neutron balance equation incorporates production (νΣ_f φ, where ν is neutrons per fission, Σ_f fission cross-section, φ flux), absorption in fuel and non-fuel, and leakage; fast spectra minimize coolant and cladding captures (e.g., sodium's low macroscopic absorption cross-section aids this). Doppler broadening of resonances provides negative reactivity feedback as fuel temperature rises, stabilizing the core against power excursions, while the hard spectrum enables higher burnup (up to 20% or more) by sustaining fission of transuranics. Thermal breeder concepts, such as thorium cycles, demand exceptional economy (e.g., via heavy water moderation) but yield marginal BR near 1.0 due to inherent thermal losses.[12][14]Historical Development

Origins and Early Experiments (1940s-1950s)

The concept of a breeder reactor, which generates more fissile material than it consumes, originated during the early 1940s amid the United States' wartime atomic energy program under the Manhattan Project. Scientists, including those at the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago, identified the potential to utilize abundant uranium-238 through fast neutron-induced fission and transmutation into plutonium-239, addressing the scarcity of naturally occurring uranium-235. This insight stemmed from fundamental nuclear physics calculations showing that fast spectrum reactors could achieve a breeding ratio greater than one, unlike thermal reactors limited to conversion ratios below unity.[15] Post-World War II, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), established in 1946, prioritized experimental fast reactors to validate breeding principles. A precursor effort was the Clementine reactor at Los Alamos National Laboratory, the world's first plutonium-fueled fast neutron spectrum reactor, which achieved criticality on November 1, 1946, and operated until 1952 using mercury coolant. Clementine primarily tested fast reactor physics, fuel behavior, and neutronics essential for future breeders, operating at up to 25 kilowatts thermal without demonstrating net breeding but confirming key fast flux characteristics.[16] The landmark advancement came with the Experimental Breeder Reactor I (EBR-I), designed by Argonne National Laboratory and constructed at the National Reactor Testing Station in Idaho starting in 1949. This sodium-cooled fast reactor achieved initial criticality on August 20, 1951, using enriched uranium fuel. On December 20, 1951, EBR-I generated sufficient electricity to illuminate four 200-watt light bulbs, marking the first production of usable electrical power from a nuclear reactor and demonstrating fast reactor viability at 1.4 megawatts thermal.[17][18][19] EBR-I's breeding capability was experimentally verified on June 4, 1953, when isotopic analysis confirmed the production of fissile plutonium exceeding consumption, achieving a breeding ratio of approximately 1.0 in initial tests with a core of uranium-235 surrounded by a uranium-238 blanket. Operating until 1963, it produced over 500,000 hours of data on fast reactor operations, coolant performance, and fuel cycles, informing subsequent designs despite challenges like sodium leaks and fuel handling. These experiments established empirical proof of breeding's feasibility, grounded in precise neutron economy measurements, though scalability to commercial power remained unproven.[19][20]Proliferation of Prototypes (1960s-1980s)

During the 1960s to 1980s, multiple nations constructed experimental and prototype fast breeder reactors to validate breeding principles, test fuel cycles, and explore commercial scalability, driven by projections of uranium shortages and interest in plutonium recycling.[4] These efforts proliferated sodium-cooled designs, reflecting convergence on liquid metal coolants for their neutron transparency and heat transfer properties, though sodium's chemical reactivity posed persistent engineering challenges.[12] In the United States, the Experimental Breeder Reactor-II (EBR-II) reached criticality in November 1963 with a thermal power of 62.5 MW and electrical output of 20 MW, operating until 1994 and demonstrating passive safety features alongside onsite reprocessing.[4][12] The Enrico Fermi Atomic Power Plant (Fermi 1), a 200 MW thermal prototype, began operation in 1963 but suffered a partial meltdown in 1966 due to fuel assembly blockage, leading to shutdown in 1972 after low capacity factors and repair costs exceeding $100 million.[4] Later, the Fast Flux Test Facility (FFTF) started in 1980 at 400 MW thermal for fuel and materials irradiation, running until 1992 without power generation focus.[4] The United Kingdom's Prototype Fast Reactor (PFR) at Dounreay achieved grid connection in 1975 with 250 MW electrical capacity, but cumulative load factors remained below 10% due to steam generator leaks and extended outages, ceasing operations in 1994 amid funding cuts.[4][12] France's Phénix prototype, operational from 1973 at 250 MW electrical (563 MW thermal), accumulated over 35 years of runtime with a 44.6% lifetime load factor, validating high-burnup MOX fuel and breeding ratios near 1.1, though it experienced reactivity transients and sodium leaks.[4][12] Superphénix followed in 1985 as a 1200 MW electrical demonstration, but achieved less than 7% lifetime load factor before closure in 1997 from technical failures and political opposition.[4] Soviet prototypes included BN-350 in Kazakhstan, grid-connected in 1972 at nominal 350 MW electrical (750 MW thermal, effective ~135 MW due to issues), which operated until 1999 while supporting desalination and enduring a 1973 sodium fire.[4][12] The BN-600 at Beloyarsk, reaching criticality in 1980 with 600 MW electrical output, demonstrated pool-type reliability with a 71.5% load factor despite 27 sodium leaks and 14 fires by 1997, incorporating MOX fuel tests.[4][12] Other efforts encompassed Germany's KNK-II (1972-1991, 20 MW electrical) for component testing and Japan's Joyo experimental reactor (1977, 100 MW thermal), which served as an irradiation facility with limited runtime.[12]| Country | Reactor | Criticality Year | Electrical Power (MWe) | Operational Period | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | EBR-II | 1963 | 20 | 1963-1994 | Reliability in reprocessing integration[4] |

| USA | Fermi 1 | 1963 | 61 | 1963-1972 | Partial meltdown and blockages[4] |

| UK | PFR | 1974 | 250 | 1974-1994 | Steam generator leaks[4] |

| France | Phénix | 1973 | 250 | 1973-2009 | Sodium leaks and transients[4] |

| USSR | BN-350 | 1972 | 350 (nominal) | 1972-1999 | Sodium fire in 1973[4] |

| USSR | BN-600 | 1980 | 600 | 1980-present | Multiple sodium incidents[4] |

Setbacks and Continued Efforts (1990s-Present)

The French Superphénix fast breeder reactor, operational from 1986, faced repeated technical incidents including a sodium fire in 1990 and turbine hall collapse in 1990, contributing to an overall low capacity factor of approximately 14%.[21][22] Public opposition, cost overruns exceeding initial estimates, and political decisions led to its definitive shutdown in 1997, with formal decommissioning decreed in December 1998.[23][24] In the United States, the Integral Fast Reactor (IFR) program at Argonne National Laboratory, which demonstrated advanced fuel recycling and inherent safety features through tests at EBR-II up to 1994, was abruptly canceled by Congress that year for budgetary and non-technical policy reasons, halting progress toward commercialization despite successful whole-core passive shutdown demonstrations.[25][26] Japan's Monju prototype, achieving criticality in 1994, suffered a major sodium coolant leak and fire in December 1995, followed by cover-up scandals, equipment failures such as a refueling machine drop in 1997, and regulatory halts; after limited restarts, it was decommissioned in December 2016 after accumulating only 250 full-power days.[27][28] These closures reflected broader challenges including sodium handling risks, high capital costs relative to light-water reactors, and heightened anti-nuclear sentiment amplified by events like Chernobyl in 1986, which prioritized short-term economics and safety perceptions over long-term fuel cycle benefits. Russia sustained operations with the BN-600 reactor at Beloyarsk, which entered commercial service in 1980 and received a license extension to 2025, accumulating over 40 years of experience in sodium-cooled fast reactor management. The BN-800 unit at the same site achieved grid connection in 2015, full commercial operation by November 2016, and transitioned to 100% mixed oxide (MOX) fuel loading in 2023, demonstrating breeding capabilities with a design conversion ratio exceeding 1.0.[29][30] China commissioned its first CFR-600 prototype in Fujian province, reaching low-power operation by mid-2023 as part of Generation IV development for enhanced uranium utilization and waste transmutation, with a second unit under construction since 2020 and grid connection anticipated by 2025.[31][32] In India, the 500 MWe Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor (PFBR) at Kalpakkam advanced to integrated commissioning stages by 2024, receiving regulatory approval for fuel loading and targeting first criticality in 2025-2026 despite construction delays from 2004, aiming to breed plutonium-239 from uranium-238 in a closed thorium-uranium cycle.[33][34] These efforts underscore persistent interest in fast breeders for extending fissile resources—potentially multiplying uranium efficiency by 60 times through breeding—and reducing long-lived actinide waste via fission, as outlined in IAEA assessments of fast reactor sustainability.[35] Ongoing R&D focuses on mitigating sodium risks through alternative coolants like lead or gas in some designs, alongside pyroprocessing for proliferation-resistant reprocessing, though economic viability hinges on scaling beyond prototypes amid fluctuating energy markets.[12]Types of Breeder Reactors

Fast Breeder Reactors

Fast breeder reactors (FBRs) operate in the fast neutron spectrum without a moderator, enabling a breeding ratio greater than unity by converting fertile uranium-238 into fissile plutonium-239 more efficiently than in thermal reactors.[12] The fast neutron flux reduces parasitic neutron capture and enhances fission in plutonium, allowing the core to be surrounded by a uranium blanket where breeding occurs predominantly.[36] This design achieves higher neutron economy, with potential energy extraction from natural uranium increased by a factor of 60 to 70 compared to light-water reactors.[2] FBRs feature compact cores with high power density, necessitating liquid metal coolants such as sodium for effective heat removal due to its high thermal conductivity and low neutron absorption.[12] Sodium-cooled fast reactors (SFRs), the predominant type, maintain coolant temperatures around 550°C, enabling high thermodynamic efficiency but introducing challenges like sodium's reactivity with water and air, leading to potential leaks and fires.[36] Alternative coolants like lead or lead-bismuth eutectic mitigate some sodium issues but pose corrosion and opacity concerns.[37] Fuel typically consists of mixed oxide (MOX) of plutonium and uranium in the core, with depleted uranium blankets for breeding; reprocessing recovers plutonium for recycling in a closed fuel cycle.[38] The Experimental Breeder Reactor-I (EBR-I) in the United States achieved criticality in 1951 and generated 200 kW of electricity on December 20, 1951, marking the first demonstration of breeding.[18] Operational examples include Russia's BN-600, a 600 MWe sodium-cooled reactor connected to the grid in 1980 and still producing power as of 2021, using MOX fuel.[12] Other prototypes faced setbacks: France's Superphénix (1200 MWe) operated intermittently from 1986 but was decommissioned in 1997 after sodium leaks and political opposition; Japan's Monju suffered multiple sodium fires and was defueled in 2016.[4] These incidents highlight sodium handling difficulties, including corrosion and void coefficient reactivity effects requiring passive safety features like natural circulation cooling.[38] Despite technical viability demonstrated in long-running units like BN-600, commercial deployment has been limited by high capital costs, reprocessing infrastructure needs, and proliferation risks from separated plutonium.[4] Ongoing developments, such as Russia's BN-800 (operational since 2016), aim for improved economics and safety through advanced designs.[12] FBRs offer sustainability benefits, including extended uranium resource utilization and transmutation of minor actinides to reduce long-lived waste, but realization depends on overcoming economic hurdles and demonstrating reliable closed-cycle operation.[39] Approximately 20 fast neutron reactors have operated worldwide since the 1950s, with current focus on Generation IV concepts emphasizing inherent safety and fuel efficiency.[12]Thermal Breeder Reactors

Thermal breeder reactors sustain fission chain reactions using thermalized neutrons while generating more fissile material than they consume, primarily through the conversion of thorium-232 to uranium-233.[40] This contrasts with uranium-plutonium cycles dominant in fast breeders, as uranium-238 captures neutrons inefficiently in thermal spectra due to parasitic absorptions exceeding breeding gains.[41] Achieving a breeding ratio greater than unity demands exceptional neutron economy, with uranium-233 fission yielding approximately 2.28 neutrons per fission to offset losses in moderators, coolant, and control materials.[40] The sole full-scale demonstration occurred at the Shippingport Atomic Power Station's Light Water Breeder Reactor (LWBR) core, a 60 MWe pressurized water design operational from August 1977 to October 1982.[41] It employed a seed-blanket configuration: highly enriched uranium-233 (over 98% U-233) pins as the fissile seed interspersed with thorium oxide blankets to capture neutrons and produce U-233 via beta decay of protactinium-233.[42] Post-irradiation analysis confirmed a net breeding gain, with a measured breeding ratio of 1.01, indicating slight excess fissile production after accounting for initial loading and fissioned material.[41] The core accumulated 29,047 effective full-power hours at a 65% capacity factor, validating thermal breeding feasibility despite cladding defects in two rods.[43] Conceptual designs for thermal breeders, such as liquid fluoride thorium reactors (LFTRs), propose molten salt fuels to enable online reprocessing, mitigating protactinium-233 absorption losses that degrade neutron economy in solid-fuel systems.[44] These liquid-fueled approaches theoretically support breeding ratios exceeding 1.05 by continuously extracting fission products and breeding intermediates, though no operational prototypes have achieved sustained power generation.[45] Challenges include corrosion from molten salts, precise isotopic separation for proliferation-resistant U-233 recovery, and the narrow margin for error in neutron balance, where even minor increases in absorption cross-sections preclude breeding.[40] Experimental efforts, like the U.S. Molten Salt Reactor Experiment (1965-1969), demonstrated U-233 operation and thorium irradiation but fell short of full breeding due to incomplete fuel cycles.[40] Current pursuits, including China's 2 MWth thorium molten salt reactor started in 2021, focus on proof-of-concept rather than commercial breeding, highlighting persistent hurdles in scaling thermal designs amid preferences for established fast breeder technologies.[40] Thermal breeders offer potential advantages in fuel abundance via thorium reserves but require innovations in materials and processing to overcome inherent neutron economy limitations compared to fast spectra.[41]Core Design Parameters

Breeding and Conversion Ratios