Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nuclear fuel

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2025) |

Nuclear fuel refers to any substance, typically fissile material, which is used by nuclear power stations or other nuclear devices to generate energy.

Oxide fuel

[edit]For fission reactors, the fuel (typically based on uranium) is usually based on the metal oxide; the oxides are used rather than the metals themselves because the oxide melting point is much higher than that of the metal and because it cannot burn, being already in the oxidized state.

Uranium dioxide

[edit]Uranium dioxide is a black semiconducting solid. It can be made by heating uranyl nitrate to form UO

2.

- UO2(NO3)2 · 6 H2O → UO2 + 2 NO2 + ½ O2 + 6 H2O (g)

This is then converted by heating with hydrogen to form UO2. It can be made from enriched uranium hexafluoride by reacting with ammonia to form a solid called ammonium diuranate, (NH4)2U2O7. This is then heated (calcined) to form UO

3 and U3O8 which is then converted by heating with hydrogen or ammonia to form UO2.[1] The UO2 is mixed with an organic binder and pressed into pellets. The pellets are then fired at a much higher temperature (in hydrogen or argon) to sinter the solid. The aim is to form a dense solid which has few pores.

The thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide is very low compared with that of zirconium metal, and it goes down as the temperature goes up. Corrosion of uranium dioxide in water is controlled by similar electrochemical processes to the galvanic corrosion of a metal surface.

While exposed to the neutron flux during normal operation in the core environment, a small percentage of the 238U in the fuel absorbs excess neutrons and is transmuted into 239U. 239U rapidly decays into 239Np which in turn rapidly decays into 239Pu. The small percentage of 239Pu has a higher neutron cross section than 235U. As the 239Pu accumulates the chain reaction shifts from pure 235U at initiation of the fuel use to a ratio of about 70% 235U and 30% 239Pu at the end of the 18 to 24 month fuel exposure period.[2]

MOX

[edit]Mixed oxide, or MOX fuel, is a blend of plutonium and natural or depleted uranium which behaves similarly (though not identically) to the enriched uranium feed for which most nuclear reactors were designed. MOX fuel is an alternative to low enriched uranium (LEU) fuel used in the light water reactors which predominate nuclear power generation.

Some concern has been expressed that used MOX cores will introduce new disposal challenges, though MOX is a means to dispose of surplus plutonium by transmutation. Reprocessing of commercial nuclear fuel to make MOX was done in the Sellafield MOX Plant (England). As of 2015, MOX fuel is made in France at the Marcoule Nuclear Site, and to a lesser extent in Russia at the Mining and Chemical Combine, India and Japan. China plans to develop fast breeder reactors and reprocessing.

The Global Nuclear Energy Partnership was a U.S. proposal in the George W. Bush administration to form an international partnership to see spent nuclear fuel reprocessed in a way that renders the plutonium in it usable for nuclear fuel but not for nuclear weapons. Reprocessing of spent commercial-reactor nuclear fuel has not been permitted in the United States due to nonproliferation considerations. All other reprocessing nations have long had nuclear weapons from military-focused research reactor fuels except for Japan. Normally, with the fuel being changed every three years or so, about half of the 239Pu is 'burned' in the reactor, providing about one third of the total energy. It behaves like 235U and its fission releases a similar amount of energy. The higher the burnup, the more plutonium is present in the spent fuel, but the available fissile plutonium is lower. Typically about one percent of the used fuel discharged from a reactor is plutonium, and some two thirds of this is fissile (c. 50% 239Pu, 15% 241Pu).

Metal fuel

[edit]Metal fuels have the advantage of a much higher heat conductivity than oxide fuels but cannot survive equally high temperatures. Metal fuels have a long history of use, stretching from the Clementine reactor in 1946 to many test and research reactors. Metal fuels have the potential for the highest fissile atom density. Metal fuels are normally alloyed, but some metal fuels have been made with pure uranium metal. Uranium alloys that have been used include uranium aluminum, uranium zirconium, uranium silicon, uranium molybdenum, uranium zirconium hydride (UZrH), and uranium zirconium carbonitride.[3] Any of the aforementioned fuels can be made with plutonium and other actinides as part of a closed nuclear fuel cycle. Metal fuels have been used in light-water reactors and liquid metal fast breeder reactors, such as Experimental Breeder Reactor II.

TRIGA fuel

[edit]TRIGA fuel is used in TRIGA (Training, Research, Isotopes, General Atomics) reactors. The TRIGA reactor uses UZrH fuel, which has a prompt negative fuel temperature coefficient of reactivity, meaning that as the temperature of the core increases, the reactivity decreases—so it is highly unlikely for a meltdown to occur. Most cores that use this fuel are "high leakage" cores where the excess leaked neutrons can be utilized for research. That is, they can be used as a neutron source. TRIGA fuel was originally designed to use highly enriched uranium, however in 1978 the U.S. Department of Energy launched its Reduced Enrichment for Research Test Reactors program, which promoted reactor conversion to low-enriched uranium fuel. There are 35 TRIGA reactors in the US and an additional 35 in other countries.

Actinide fuel

[edit]In a fast-neutron reactor, the minor actinides produced by neutron capture of uranium and plutonium can be used as fuel. Metal actinide fuel is typically an alloy of zirconium, uranium, plutonium, and minor actinides. It can be made inherently safe as thermal expansion of the metal alloy will increase neutron leakage.

Molten plutonium

[edit]Molten plutonium, alloyed with other metals to lower its melting point and encapsulated in tantalum,[4] was tested in two experimental reactors, LAMPRE I and LAMPRE II, at Los Alamos National Laboratory in the 1960s. LAMPRE experienced three separate fuel failures during operation.[5]

Non-oxide ceramic fuels

[edit]Ceramic fuels other than oxides have the advantage of high heat conductivities and melting points, but they are more prone to swelling than oxide fuels and are not understood as well.

Uranium nitride

[edit]Uranium nitride is often the fuel of choice for reactor designs that NASA produces. One advantage is that uranium nitride has a better thermal conductivity than UO2. Uranium nitride has a very high melting point. This fuel has the disadvantage that unless 15N was used (in place of the more common 14N), a large amount of 14C would be generated from the nitrogen by the (n,p) reaction.

As the nitrogen needed for such a fuel would be so expensive it is likely that the fuel would require pyroprocessing to enable recovery of the 15N. It is likely that if the fuel was processed and dissolved in nitric acid that the nitrogen enriched with 15N would be diluted with the common 14N. Fluoride volatility is a method of reprocessing that does not rely on nitric acid, but it has only been demonstrated in relatively small scale installations whereas the established PUREX process is used commercially for about a third of all spent nuclear fuel (the rest being largely subject to a "once through fuel cycle").

All nitrogen-fluoride compounds are volatile or gaseous at room temperature and could be fractionally distilled from the other gaseous products (including recovered uranium hexafluoride) to recover the initially used nitrogen. If the fuel could be processed in such a way as to ensure low contamination with non-radioactive carbon (not a common fission product and absent in nuclear reactors that don't use it as a moderator) then fluoride volatility could be used to separate the 14

C produced by producing carbon tetrafluoride. 14

C is proposed for use in particularly long lived low power nuclear batteries called diamond batteries.

Uranium carbide

[edit]Much of what is known about uranium carbide is in the form of pin-type fuel elements for liquid metal fast reactors during their intense study in the 1960s and 1970s. Recently there has been a revived interest in uranium carbide in the form of plate fuel and most notably, micro fuel particles (such as tristructural-isotropic particles).

The high thermal conductivity and high melting point makes uranium carbide an attractive fuel. In addition, because of the absence of oxygen in this fuel (during the course of irradiation, excess gas pressure can build from the formation of O2 or other gases) as well as the ability to complement a ceramic coating (a ceramic-ceramic interface has structural and chemical advantages), uranium carbide could be the ideal fuel candidate for certain Generation IV reactors such as the gas-cooled fast reactor. While the neutron cross section of carbon is low, during years of burnup, the predominantly 12

C will undergo neutron capture to produce stable 13

C as well as radioactive 14

C. Unlike the 14

C produced by using uranium nitrate, the 14

C will make up only a small isotopic impurity in the overall carbon content and thus make the entirety of the carbon content unsuitable for non-nuclear uses but the 14

C concentration will be too low for use in nuclear batteries without enrichment. Nuclear graphite discharged from reactors where it was used as a moderator presents the same issue.

Liquid fuels

[edit]Liquid fuels contain dissolved nuclear fuel and have been shown to offer numerous operational advantages compared to traditional solid fuel approaches.[6] Liquid-fuel reactors offer significant safety advantages due to their inherently stable "self-adjusting" reactor dynamics. This provides two major benefits: virtually eliminating the possibility of a runaway reactor meltdown, and providing an automatic load-following capability which is well suited to electricity generation and high-temperature industrial heat applications.

In some liquid core designs, the fuel can be drained rapidly into a passively safe dump-tank. This advantage was conclusively demonstrated repeatedly as part of a weekly shutdown procedure during the highly successful Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment from 1965 to 1969.

A liquid core is able to release xenon gas, which normally acts as a neutron absorber (135

Xe is the strongest known neutron poison and is produced both directly and as a decay product of 135

I as a fission product) and causes structural occlusions in solid fuel elements (leading to the early replacement of solid fuel rods with over 98% of the nuclear fuel unburned, including many long-lived actinides). In contrast, molten-salt reactors are capable of retaining the fuel mixture for significantly extended periods, which increases fuel efficiency dramatically and incinerates the vast majority of its own waste as part of the normal operational characteristics. A downside to letting the 135

Xe escape instead of allowing it to capture neutrons converting it to the basically stable and chemically inert 136

Xe, is that it will quickly decay to the highly chemically reactive, long lived radioactive 135

Cs, which behaves similar to other alkali metals and can be taken up by organisms in their metabolism.

Molten salts

[edit]Molten salt fuels are mixtures of actinide salts (e.g. thorium/uranium fluoride/chloride) with other salts, used in liquid form above their typical melting points of several hundred degrees C. In some molten salt-fueled reactor designs, such as the liquid fluoride thorium reactor (LFTR), this fuel salt is also the coolant; in other designs, such as the stable salt reactor, the fuel salt is contained in fuel pins and the coolant is a separate, non-radioactive salt. There is a further category of molten salt-cooled reactors in which the fuel is not in molten salt form, but a molten salt is used for cooling.

Molten salt fuels were used in the LFTR known as the Molten Salt Reactor Experiment, as well as other liquid core reactor experiments. The liquid fuel for the molten salt reactor was a mixture of lithium, beryllium, thorium and uranium fluorides: LiF-BeF2-ThF4-UF4 (72-16-12-0.4 mol%). It had a peak operating temperature of 705 °C in the experiment, but could have operated at much higher temperatures since the boiling point of the molten salt was in excess of 1400 °C.

Aqueous solutions of uranyl salts

[edit]The aqueous homogeneous reactors (AHRs) use a solution of uranyl sulfate or other uranium salt in water. Historically, AHRs have all been small research reactors, not large power reactors.

Liquid metals or alloys

[edit]The dual fluid reactor (DFR) has a variant DFR/m which works with eutectic liquid metal alloys, e.g. U-Cr or U-Fe.[7]

Common physical forms

[edit]Uranium dioxide (UO2) powder is compacted to cylindrical pellets and sintered at high temperatures to produce ceramic nuclear fuel pellets with a high density and well defined physical properties and chemical composition. A grinding process is used to achieve a uniform cylindrical geometry with narrow tolerances. Such fuel pellets are then stacked and filled into the metallic tubes. The metal used for the tubes depends on the design of the reactor. Stainless steel was used in the past, but most reactors now use a zirconium alloy which, in addition to being highly corrosion-resistant, has low neutron absorption. The tubes containing the fuel pellets are sealed: these tubes are called fuel rods. The finished fuel rods are grouped into fuel assemblies that are used to build up the core of a power reactor.

Cladding is the outer layer of the fuel rods, standing between the coolant and the nuclear fuel. It is made of a corrosion-resistant material with low absorption cross section for thermal neutrons, usually Zircaloy or steel in modern constructions, or magnesium with small amount of aluminium and other metals for the now-obsolete Magnox reactors. Cladding prevents radioactive fission fragments from escaping the fuel into the coolant and contaminating it. Besides the prevention of radioactive leaks this also serves to keep the coolant as non-corrosive as feasible and to prevent reactions between chemically aggressive fission products and the coolant. For example, the highly reactive alkali metal caesium which reacts strongly with water, producing hydrogen, and which is among the more common fission products.[a]

-

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) photo of unirradiated (fresh) fuel pellets.

-

NRC photo of fresh fuel pellets ready for assembly.

-

NRC photo of fresh fuel assemblies being inspected.

Pressurized water reactor fuel

[edit]Pressurized water reactor (PWR) fuel consists of cylindrical rods put into bundles. A uranium oxide ceramic is formed into pellets and inserted into Zircaloy tubes that are bundled together. The Zircaloy tubes are about 1 centimetre (0.4 in) in diameter, and the fuel cladding gap is filled with helium gas to improve heat conduction from the fuel to the cladding. There are about 179–264 fuel rods per fuel bundle and about 121 to 193 fuel bundles are loaded into a reactor core. Generally, the fuel bundles consist of fuel rods bundled 14×14 to 17×17. PWR fuel bundles are about 4 m (13 ft) long. In PWR fuel bundles, control rods are inserted through the top directly into the fuel bundle. The fuel bundles usually are enriched several percent in 235U. The uranium oxide is dried before inserting into the tubes to try to eliminate moisture in the ceramic fuel that can lead to corrosion and hydrogen embrittlement. The Zircaloy tubes are pressurized with helium to try to minimize pellet-cladding interaction which can lead to fuel rod failure over long periods. Over time, thermal expansion and fission gas release cause the fuel pellets to crack and deform into an 'hourglass' shape, which in turn leads to a characteristic 'bamboo '- like deformation of the cladding. These mechanical interactions can stress the cladding, especially as internal rod pressure increases and fuel swelling continues throughout irradiation.[citation needed]

Boiling water reactor fuel

[edit]In boiling water reactors (BWR), the fuel is similar to PWR fuel except that the bundles are "canned". That is, there is a thin tube surrounding each bundle. This is primarily done to prevent local density variations from affecting neutronics and thermal hydraulics of the reactor core. In modern BWR fuel bundles, there are either 91, 92, or 96 fuel rods per assembly depending on the manufacturer. A range between 368 assemblies for the smallest and 800 assemblies for the largest BWR in the U.S. form the reactor core. Each BWR fuel rod is backfilled with helium to a pressure of about 3 standard atmospheres (300 kPa).

Canada deuterium uranium fuel

[edit]Canada deuterium uranium fuel (CANDU) fuel bundles are about 0.5 metres (20 in) long and 10 centimetres (4 in) in diameter. They consist of sintered (UO2) pellets in zirconium alloy tubes, welded to zirconium alloy end plates. Each bundle weighs roughly 20 kilograms (44 lb), and a typical core loading is on the order of 4500–6500 bundles, depending on the design. Modern types typically have 37 identical fuel pins radially arranged about the long axis of the bundle, but in the past several different configurations and numbers of pins have been used. The CANFLEX bundle has 43 fuel elements, with two element sizes. It is also about 10 cm (4 inches) in diameter, 0.5 m (20 in) long and weighs about 20 kg (44 lb) and replaces the 37-pin standard bundle. It has been designed specifically to increase fuel performance by utilizing two different pin diameters. Current CANDU designs do not need enriched uranium to achieve criticality (due to the lower neutron absorption in their heavy water moderator compared to light water), however, some newer concepts call for low enrichment to help reduce the size of the reactors. The Atucha nuclear power plant in Argentina, a similar design to the CANDU but built by German KWU was originally designed for non-enriched fuel but since switched to slightly enriched fuel with a 235

U content about 0.1 percentage points higher than in natural uranium.

Less-common fuel forms

[edit]Various other nuclear fuel forms find use in specific applications, but lack the widespread use of those found in BWRs, PWRs, and CANDU power plants. Many of these fuel forms are only found in research reactors, or have military applications.

Magnox fuel

[edit]Magnox (magnesium non-oxidising) reactors are pressurised, carbon dioxide–cooled, graphite-moderated reactors using natural uranium (i.e. unenriched) as fuel and Magnox alloy as fuel cladding. Working pressure varies from 6.9 to 19.35 bars (100.1 to 280.6 psi) for the steel pressure vessels, and the two reinforced concrete designs operated at 24.8 and 27 bars (24.5 and 26.6 atm). Magnox alloy consists mainly of magnesium with small amounts of aluminium and other metals—used in cladding unenriched uranium metal fuel with a non-oxidising covering to contain fission products. This material has the advantage of a low neutron capture cross-section, but has two major disadvantages:

- It limits the maximum temperature, and hence the thermal efficiency, of the plant.

- It reacts with water, preventing long-term storage of spent fuel under water - such as in a spent fuel pool.

Magnox fuel incorporated cooling fins to provide maximum heat transfer despite low operating temperatures, making it expensive to produce. While the use of uranium metal rather than oxide made nuclear reprocessing more straightforward and therefore cheaper, the need to reprocess fuel a short time after removal from the reactor meant that the fission product hazard was severe. Expensive remote handling facilities were required to address this issue.

Tristructural-isotropic fuel

[edit]

Tristructural-isotropic (TRISO) fuel is a type of micro-particle fuel. A particle consists of a kernel of UOX fuel (sometimes UC or UCO), which has been coated with four layers of three isotropic materials deposited through fluidized chemical vapor deposition (FCVD). The four layers are a porous buffer layer made of carbon that absorbs fission product recoils, followed by a dense inner layer of protective pyrolytic carbon (PyC), followed by a ceramic layer of SiC to retain fission products at elevated temperatures and to give the TRISO particle more structural integrity, followed by a dense outer layer of PyC. TRISO particles are then encapsulated into cylindrical or spherical graphite pellets. TRISO fuel particles are designed not to crack due to the stresses from processes (such as differential thermal expansion or fission gas pressure) at temperatures up to 1600 °C, and therefore can contain the fuel in the worst of accident scenarios in a properly designed reactor. Two such reactor designs are the prismatic-block gas-cooled reactor (such as the GT-MHR) and the pebble-bed reactor (PBR). Both of these reactor designs are high temperature gas reactors (HTGRs). These are also the basic reactor designs of very-high-temperature reactors (VHTRs), one of the six classes of reactor designs in the Generation IV initiative that is attempting to reach even higher HTGR outlet temperatures.

TRISO fuel particles were originally developed in the United Kingdom as part of the Dragon reactor project. The inclusion of the SiC as diffusion barrier was first suggested by D. T. Livey.[8] The first nuclear reactor to use TRISO fuels was the Dragon reactor and the first powerplant was the THTR-300. Currently, TRISO fuel compacts are being used in some experimental reactors, such as the HTR-10 in China and the high-temperature engineering test reactor in Japan. In the United States, spherical fuel elements utilizing a TRISO particle with a UO2 and UC solid solution kernel are being used in the Xe-100, and Kairos Power is developing a 140 MWE nuclear reactor that uses TRISO.[9]

QUADRISO fuel

[edit]

In QUADRISO particles a burnable neutron poison (europium oxide or erbium oxide or carbide) layer surrounds the fuel kernel of ordinary TRISO particles to better manage the excess of reactivity. If the core is equipped both with TRISO and QUADRISO fuels, at beginning of life neutrons do not reach the fuel of the QUADRISO particles because they are stopped by the burnable poison. During reactor operation, neutron irradiation of the poison causes it to "burn up" or progressively transmute to non-poison isotopes, depleting this poison effect and leaving progressively more neutrons available for sustaining the chain-reaction. This mechanism compensates for the accumulation of undesirable neutron poisons which are an unavoidable part of the fission products, as well as normal fissile fuel "burn up" or depletion. In the generalized QUADRISO fuel concept the poison can eventually be mixed with the fuel kernel or the outer pyrocarbon. The QUADRISO[10] concept was conceived at Argonne National Laboratory.

RBMK fuel

[edit]RBMK reactor fuel was used in Soviet-designed and built RBMK-type reactors. This is a low-enriched uranium oxide fuel. The fuel elements in an RBMK are 3 m long each, and two of these sit back-to-back on each fuel channel, pressure tube. Reprocessed uranium from Russian VVER reactor spent fuel is used to fabricate RBMK fuel. Following the Chernobyl accident, the enrichment of fuel was changed from 2.0% to 2.4%, to compensate for control rod modifications and the introduction of additional absorbers.

CerMet fuel

[edit]CerMet fuel consists of ceramic fuel particles (usually uranium oxide) embedded in a metal matrix. It is hypothesized[by whom?] that this type of fuel is what is used in United States Navy reactors. This fuel has high heat transport characteristics and can withstand a large amount of expansion.

Plate-type fuel

[edit]

Plate-type fuel has fallen out of favor over the years. Plate-type fuel is commonly composed of enriched uranium sandwiched between metal cladding. Plate-type fuel is used in several research reactors where a high neutron flux is desired, for uses such as material irradiation studies or isotope production, without the high temperatures seen in ceramic, cylindrical fuel. It is currently used in the Advanced Test Reactor (ATR) at Idaho National Laboratory, and the nuclear research reactor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell Radiation Laboratory.[citation needed]

Sodium-bonded fuel

[edit]Sodium-bonded fuel consists of fuel that has liquid sodium in the gap between the fuel slug (or pellet) and the cladding. This fuel type is often used for sodium-cooled liquid metal fast reactors. It has been used in EBR-I, EBR-II, and the FFTF. The fuel slug may be metallic or ceramic. The sodium bonding is used to reduce the temperature of the fuel.

Accident tolerant fuels

[edit]Accident tolerant fuels (ATF) are a series of new nuclear fuel concepts, researched in order to improve fuel performance under accident conditions, such as loss-of-coolant accident (LOCA) or reaction-initiated accidents (RIA). These concerns became more prominent after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan, in particular regarding light-water reactor (LWR) fuels performance under accident conditions.[11]

Neutronics analyses were performed for the application of the new fuel-cladding material systems for various types of ATF materials.[12]

The aim of the research is to develop nuclear fuels that can tolerate loss of active cooling for a considerably longer period than the existing fuel designs and prevent or delay the release of radionuclides during an accident.[13] This research is focused on reconsidering the design of fuel pellets and cladding,[14][15] as well as the interactions between the two.[16][12][17][18][19]

Spent nuclear fuel

[edit]Used nuclear fuel is a complex mixture of the fission products, uranium, plutonium, and the transplutonium metals. In fuel which has been used at high temperature in power reactors it is common for the fuel to be heterogeneous; often the fuel will contain nanoparticles of platinum group metals such as palladium. Also the fuel may well have cracked, swollen, and been heated close to its melting point. Despite the fact that the used fuel can be cracked, it is very insoluble in water, and is able to retain the vast majority of the actinides and fission products within the uranium dioxide crystal lattice. The radiation hazard from spent nuclear fuel declines as its radioactive components decay, but remains high for many years. For example 10 years after removal from a reactor, the surface dose rate for a typical spent fuel assembly still exceeds 10,000 rem/hour, resulting in a fatal dose in just minutes.[20]

Oxide fuel under accident conditions

[edit]Two main modes of release exist, the fission products can be vaporised or small particles of the fuel can be dispersed.

Fuel behavior and post-irradiation examination

[edit]Post-Irradiation Examination (PIE) is the study of used nuclear materials such as nuclear fuel. It has several purposes. It is known that by examination of used fuel that the failure modes which occur during normal use (and the manner in which the fuel will behave during an accident) can be studied. In addition information is gained which enables the users of fuel to assure themselves of its quality and it also assists in the development of new fuels. After major accidents the core (or what is left of it) is normally subject to PIE to find out what happened. One site where PIE is done is the ITU which is the EU centre for the study of highly radioactive materials.

Materials in a high-radiation environment (such as a reactor) can undergo unique behaviors such as swelling[21] and non-thermal creep. If there are nuclear reactions within the material (such as what happens in the fuel), the stoichiometry will also change slowly over time. These behaviors can lead to new material properties, cracking, and fission gas release.

The thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide is low; it is affected by porosity and burn-up. The burn-up results in fission products being dissolved in the lattice (such as lanthanides), the precipitation of fission products such as palladium, the formation of fission gas bubbles due to fission products such as xenon and krypton and radiation damage of the lattice. The low thermal conductivity can lead to overheating of the center part of the pellets during use. The porosity results in a decrease in both the thermal conductivity of the fuel and the swelling which occurs during use.

According to the International Nuclear Safety Center[22] the thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide can be predicted under different conditions by a series of equations.

The bulk density of the fuel can be related to the thermal conductivity.

Where ρ is the bulk density of the fuel and ρtd is the theoretical density of the uranium dioxide.

Then the thermal conductivity of the porous phase (Kf) is related to the conductivity of the perfect phase (Ko, no porosity) by the following equation. Note that s is a term for the shape factor of the holes.

- Kf = Ko(1 − p/1 + (s − 1)p)

Rather than measuring the thermal conductivity using the traditional methods such as Lees' disk, the Forbes' method, or Searle's bar, it is common to use Laser Flash Analysis where a small disc of fuel is placed in a furnace. After being heated to the required temperature one side of the disc is illuminated with a laser pulse, the time required for the heat wave to flow through the disc, the density of the disc, and the thickness of the disk can then be used to calculate and determine the thermal conductivity.

- λ = ρCpα

If t1/2 is defined as the time required for the non illuminated surface to experience half its final temperature rise then.

- α = 0.1388 L2/t1/2

- L is the thickness of the disc

For details see K. Shinzato and T. Baba (2001).[23]

Radioisotope decay fuels

[edit]Radioisotope battery

[edit]An atomic battery (also called a nuclear battery or radioisotope battery) is a device which uses the radioactive decay to generate electricity. These systems use radioisotopes that produce low energy beta particles or sometimes alpha particles of varying energies. Low energy beta particles are needed to prevent the production of high energy penetrating bremsstrahlung radiation that would require heavy shielding. Radioisotopes such as plutonium-238, curium-242, curium-244 and strontium-90 have been used. Tritium, nickel-63, promethium-147, and technetium-99 have been tested.

There are two main categories of atomic batteries: thermal and non-thermal. The non-thermal atomic batteries, which have many different designs, exploit charged alpha and beta particles. These designs include the direct charging generators, betavoltaics, the optoelectric nuclear battery, and the radioisotope piezoelectric generator. The thermal atomic batteries on the other hand, convert the heat from the radioactive decay to electricity. These designs include thermionic converter, thermophotovoltaic cells, alkali-metal thermal to electric converter, and the most common design, the radioisotope thermoelectric generator.

Radioisotope thermoelectric generator

[edit]

A radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) is a simple electrical generator which converts heat into electricity from a radioisotope using an array of thermocouples.

238

Pu has become the most widely used fuel for RTGs, in the form of plutonium dioxide. It has a half-life of 87.7 years, reasonable energy density, and exceptionally low gamma and neutron radiation levels. Some Russian terrestrial RTGs have used 90

Sr; this isotope has a shorter half-life and a much lower energy density, but is cheaper. Early RTGs, first built in 1958 by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, have used 210

Po. This fuel provides phenomenally huge energy density, (a single gram of polonium-210 generates 140 watts thermal) but has limited use because of its very short half-life and gamma production, and has been phased out of use for this application.

Radioisotope heater unit (RHU)

[edit]A radioisotope heater unit (RHU) typically provides about 1 watt of heat each, derived from the decay of a few grams of plutonium-238. This heat is given off continuously for several decades.

Their function is to provide highly localised heating of sensitive equipment (such as electronics in outer space). The Cassini–Huygens orbiter to Saturn contains 82 of these units (in addition to its 3 main RTGs for power generation). The Huygens probe to Titan contains 35 devices.

Fusion fuels

[edit]Fusion fuels are fuels to use in hypothetical Fusion power reactors. They include deuterium (2H) and tritium (3H) as well as helium-3 (3He). Many other elements can be fused together, but the larger electrical charge of their nuclei means that much higher temperatures are required. Only the fusion of the lightest elements is seriously considered as a future energy source. Fusion of the lightest atom, 1H hydrogen, as is done in the Sun and other stars, has also not been considered practical on Earth. Although the energy density of fusion fuel is even higher than fission fuel, and fusion reactions sustained for a few minutes have been achieved, utilizing fusion fuel as a net energy source remains only a theoretical possibility.[24]

First-generation fusion fuel

[edit]Deuterium and tritium are both considered first-generation fusion fuels; they are the easiest to fuse, because the electrical charge on their nuclei is the lowest of all elements. The three most commonly cited nuclear reactions that could be used to generate energy are:

- 2H + 3H → n (14.07 MeV) + 4He (3.52 MeV)

- 2H + 2H → n (2.45 MeV) + 3He (0.82 MeV)

- 2H + 2H → p (3.02 MeV) + 3H (1.01 MeV)

Second-generation fusion fuel

[edit]Second-generation fuels require either higher confinement temperatures or longer confinement time than those required of first-generation fusion fuels, but generate fewer neutrons. Neutrons are an unwanted byproduct of fusion reactions in an energy generation context, because they are absorbed by the walls of a fusion chamber, making them radioactive. They cannot be confined by magnetic fields, because they are not electrically charged. This group consists of deuterium and helium-3. The products are all charged particles, but there may be significant side reactions leading to the production of neutrons.

- 2H + 3He → p (14.68 MeV) + 4He (3.67 MeV)

Third-generation fusion fuel

[edit]Third-generation fusion fuels produce only charged particles in the primary reactions, and side reactions are relatively unimportant. Since a very small amount of neutrons is produced, there would be little induced radioactivity in the walls of the fusion chamber. This is often seen as the end goal of fusion research. 3He has the highest Maxwellian reactivity of any 3rd generation fusion fuel. However, there are no significant natural sources of this substance on Earth.

- 3He + 3He → 2 p + 4He (12.86 MeV)

Another potential aneutronic fusion reaction is the proton-boron reaction:

- p + 11B → 3 4He (8.7 MeV)

Under reasonable assumptions, side reactions will result in about 0.1% of the fusion power being carried by neutrons. With 123 keV, the optimum temperature for this reaction is nearly ten times higher than that for the pure hydrogen reactions, the energy confinement must be 500 times better than that required for the D-T reaction, and the power density will be 2500 times lower than for D-T.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The fission product yields of both 135

Cs and 137

Cs are roughly 6%, meaning every kilogram of 235

U split will result in roughly 35 grams each of 135

Cs and 137

Cs). Besides those well-known middle to long-lived radioactive caesium isotopes there are other isotopes of caesium like 133

Cs (stable) and 134

Cs (half life around two years) that are present in "fresh" spent nuclear fuel in non-trivial amounts

References

[edit]- ^ R. Norris Shreve; Joseph Brink (1977). Chemical Process Industries (4th ed.). pp. 338–341. ASIN B000OFVCCG.

- ^ "Uranium Fuel Cycle | nuclear-power.com". Nuclear Power. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ^ Bulatov, G. S.; German, Konstantin E. (December 2022). "New Experimental Data on Partial Pressures of Gas Phase Components over Uranium-Zirconium Carbonitrides at High Temperatures and Its Comparative Analysis". Journal of Nuclear Engineering. 3 (4): 352–363. doi:10.3390/jne3040022. ISSN 2673-4362.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-21. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "LAHDRA: Los Alamos Historical Document Retrieval and Assessment Project" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-15. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ Hargraves, Robert. "Liquid Fuel Nuclear Reactors". Forum on Physics and Society. APS Physics. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Dual Fluid Reactor – Variant with Liquid Metal Fissionable Material (DFR/ M)".

- ^ Price, M. S. T. (2012). "The Dragon Project origins, achievements and legacies". Nucl. Eng. Design. 251: 60–68. Bibcode:2012NuEnD.251...60P. doi:10.1016/j.nucengdes.2011.12.024.

- ^ "Technology". Kairos Power. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ Alberto Talamo (July 2010) A novel concept of QUADRISO particles. Part II: Utilization for excess reactivity control

- ^ Kim, Hyun-Gil; Yang, Jae-Ho; Kim, Weon-Ju; Koo, Yang-Hyun (2016). "Development Status of Accident-tolerant Fuel for Light WaterReactors in Korea". Nuclear Engineering and Technology. 48 (1): 1–15. Bibcode:2016NuEnT..48....1K. doi:10.1016/j.net.2015.11.011.

- ^ a b Alrwashdeh, Mohammad; Alameri, Saeed A. (2022). "SiC and FeCrAl as Potential Cladding Materials for APR-1400 Neutronic Analysis". Energies. 15 (10): 3772. doi:10.3390/en15103772.

- ^ Zinkle, S.J.; Terrani, K.A.; Gehin, J.C.; Ott, L.J.; Snead, L.L. (May 2014). "Accident tolerant fuels for LWRs: A perspective". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 448 (1–3): 374–379. Bibcode:2014JNuM..448..374Z. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.12.005.

- ^ Alhattawi, Nouf T.; Alrwashdeh, Mohammad; Alameri, Saeed A.; Alaleeli, Maitha M. (2023-08-15). "Sensitivity neutronic analysis of accident tolerant fuel concepts in APR1400". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 582 154487. Bibcode:2023JNuM..58254487A. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2023.154487. ISSN 0022-3115.

- ^ Alrwashdeh, Mohammad; Alameri, Saeed A. (2023-05-08). "A Neutronics Study of the Initial Fuel Cycle Extension in APR-1400 Reactors: Examining Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Enrichment Design". Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering. 50 (5): 3059–3072. doi:10.1007/s13369-023-07905-7. ISSN 2191-4281.

- ^ "State-of-the-Art Report on Light Water Reactor Accident-Tolerant Fuels". www.oecd-nea.org. Retrieved 2019-03-16.

- ^ Alrwashdeh, Mohammad, and Saeed A. Alameri. "Preliminary neutronic analysis of alternative cladding materials for APR-1400 fuel assembly." Nuclear Engineering and Design 384 (2021): 111486.

- ^ Alaleeli, Maithah; Alameri, Saeed; Alrwashdeh, Mohammad (2022). "Neutronic Analysis of SiC/SiC Sandwich Cladding Design in APR-1400 under Normal Operation Conditions". Energies. 15 (14): 5204. doi:10.3390/en15145204.

- ^ Alrwashdeh, Mohammad; Alameri, Saeed A. (2022). "Chromium-Coated Zirconium Cladding Neutronics Impact for APR-1400 Reactor Core". Energies. 15 (21): 8008. doi:10.3390/en15218008.

- ^ "Backgrounder on Radioactive Waste". www.nrc.gov. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). 2021-06-23. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ^ Armin F. Lietzke (Jan 1970) Simplified Analysis of Nuclear Fuel Pin Swelling "The effect of fuel swelling on strains in the cladding of cylindrical fuel pins is analyzed. Simplifying assumptions are made to permit solutions for strain rates in terms of dimensionless parameters. The results of the analysis are presented in the form of equations and graphs which illustrate the volumetric swelling of the fuel and the strain rate of the fuel pin clad."

- ^ Nuclear Engineering Division, Argonne National Laboratory, US Department of Energy (15 January 2008) International Nuclear Safety Center (INSC)

- ^ K. Shinzato and T. Baba (2001) Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, Vol. 64 (2001) 413–422. A Laser Flash Apparatus for Thermal Diffusivity and Specific Heat Capacity Measurements

- ^ "Nuclear Fusion Power". World Nuclear Association. September 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-12-25. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

External links

[edit]PWR fuel

[edit]- "NEI fuel schematic". Archived from the original on 2004-10-22. Retrieved 2005-12-14.

- "Picture of a PWR fuel assembly". Archived from the original on 2015-04-23. Retrieved 2005-12-14.

- Picture showing handling of a PWR bundle

- "Mitsubishi nuclear fuel Co". Archived from the original on 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2005-12-14.

BWR fuel

[edit]- "Picture of a "canned" BWR assembly". Archived from the original on 2006-08-28. Retrieved 2005-12-14.

- Physical description of LWR fuel

- Links to BWR photos from the nuclear tourist webpage

CANDU fuel

[edit]- CANDU Fuel pictures and FAQ

- Basics on CANDU design

- The Evolution of CANDU Fuel Cycles and their Potential Contribution to World Peace

- "CANDU Fuel-Management Course" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-03-15. Retrieved 2005-12-17.

- CANDU Fuel and Reactor Specifics (Nuclear Tourist)

- Candu Fuel Rods and Bundles

TRISO fuel

[edit]- Alameri, Saeed A.; Alrwashdeh, Mohammad (2021). "Preliminary three-dimensional neutronic analysis of IFBA coated TRISO fuel particles in prismatic-core advanced high temperature reactor". Annals of Nuclear Energy. 163 108551. Bibcode:2021AnNuE.16308551A. doi:10.1016/j.anucene.2021.108551.

- Alrwashdeh, Mohammad; Alameri, Saeed A.; Alkaabi, Ahmed K. (2020). "Preliminary Study of a Prismatic-Core Advanced High-Temperature Reactor Fuel Using Homogenization Double-Heterogeneous Method". Nuclear Science and Engineering. 194 (2): 163–167. Bibcode:2020NSE...194..163A. doi:10.1080/00295639.2019.1672511. S2CID 209983934.

- TRISO fuel descripción

- Non-Destructive Examination of SiC Nuclear Fuel Shell using X-Ray Fluorescence Microtomography Technique

- GT-MHR fuel compact process Archived 2006-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Description of TRISO fuel for "pebbles"

- LANL webpage showing various stages of TRISO fuel production

- Method to calculate the temperature profile in TRISO fuel Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Machine

QUADRISO fuel

[edit]CERMET fuel

[edit]- "A Review of Fifty Years of Space Nuclear Fuel Development Programs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-12-30. Retrieved 2005-12-14.

- Thoria-based Cermet Nuclear Fuel: Sintered Microsphere Fabrication by Spray Drying

- "The Use of Molybdenum-Based Ceramic-Metal (CerMet) Fuel for the Actinide Management in LWRs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-03-19. Retrieved 2005-12-14.

Plate type fuel

[edit]- https://pubs.aip.org/aip/adv/article/9/7/075112/22584/Reactor-Monte-Carlo-RMC-model-validation-and

- List of reactors at INL and picture of ATR core

- ATR plate fuel

TRIGA fuel

[edit]- "General Atomics TRIGA fuel website". Archived from the original on 2005-12-23. Retrieved 2005-12-14.

Fusion fuel

[edit]- Advanced fusion fuels presentation Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Machine

Nuclear fuel

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Nuclear Fuel

Definition and Fission Principles

Nuclear fuel comprises fissile isotopes or compounds thereof that sustain a controlled nuclear fission chain reaction to produce thermal energy in reactors. The principal fissile materials are uranium-235 (U-235), plutonium-239 (Pu-239), and uranium-233 (U-233), which constitute a small fraction of natural uranium or are produced via neutron capture and subsequent reactions.[9][10] These isotopes are embedded in matrices like uranium dioxide (UO₂) ceramic pellets, which offer chemical stability and high melting points essential for withstanding reactor conditions.[3] Nuclear fission initiates when a thermal neutron is absorbed by a fissile nucleus, rendering it excited and prompting asymmetric cleavage into two fission fragments of unequal mass, typically around 95 and 135 atomic mass units for uranium. This process emits 2-3 prompt neutrons and converts approximately 0.1% of the nucleus's rest mass into kinetic energy of fragments, gamma rays, and neutron energy, yielding about 200 MeV per fission event—over a million times the energy of chemical reactions.[5][11] The chain reaction arises as emitted neutrons induce further fissions in adjacent fissile nuclei, provided the neutron multiplication factor (k) exceeds unity in a critical assembly moderated to thermalize neutrons and geometrically configured to minimize leakage. Control rods absorb excess neutrons to maintain k ≈ 1, preventing exponential power surges while extracting sustained heat for electricity generation.[12][13] Energy liberation stems from the binding energy curve, where heavy nuclei like U-235 exhibit lower binding energy per nucleon than medium-mass products, enabling exothermic rearrangement toward iron-peak stability.[5]Key Isotopes and Material Properties

The primary fissile isotopes utilized in nuclear fuel are uranium-235 (U-235), plutonium-239 (Pu-239), and uranium-233 (U-233). U-235 occurs naturally at approximately 0.72% abundance in uranium ore, with the balance dominated by fertile uranium-238 (U-238) at over 99%.[14] Pu-239 is artificially produced through neutron capture and subsequent beta decay of U-238 in reactors, enabling its use in mixed oxide (MOX) fuels. U-233, bred from thorium-232, sees limited commercial application due to proliferation concerns and material handling challenges.[14] Natural uranium's low U-235 content necessitates enrichment to 3-5% U-235 for most light-water reactors, enhancing fission probability under thermal neutron spectra. Fertile isotopes like U-238 contribute indirectly by absorbing neutrons to form Pu-239, which fissions and sustains chain reactions, accounting for up to one-third of energy output in typical fuel cycles.[1] Isotopic purity affects criticality; for instance, weapons-grade material requires >90% U-235 or >93% Pu-239, far exceeding reactor fuel specifications.[14] Nuclear fuels are predominantly ceramic oxides, with uranium dioxide (UO₂) as the standard form due to its chemical stability and compatibility with cladding. UO₂ exhibits a cubic fluorite crystal structure, theoretical density of 10.97 g/cm³, and melting point of 2865°C, enabling operation at high temperatures up to ~2000°C in reactors.[15] [16] Its thermal conductivity is low, typically 2-4 W/m·K at 500°C, which limits heat dissipation and influences fuel rod design to prevent centerline melting.[15] Mechanical properties include a Young's modulus around 200 GPa and Poisson's ratio of 0.32, with irradiation-induced swelling managed through pellet geometry.[17] Plutonium dioxide (PuO₂), incorporated in MOX at 3-7% by weight, shares a fluorite structure but possesses higher density (~11.5 g/cm³) and melting point (~2400°C), though its alpha decay heat (1.9 W/g) elevates fuel temperatures. PuO₂'s thermophysical properties, including thermal expansion coefficients similar to UO₂, facilitate blending, but neutron emission from isotopes like Pu-240 requires shielding considerations.[18] These materials' resistance to radiation damage stems from defect annealing at operational temperatures, though fission gas retention impacts long-term performance.[16]Historical Development

Early Scientific Discoveries and Manhattan Project

In December 1938, chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin discovered nuclear fission while bombarding uranium with neutrons, observing the production of barium—a fission product approximately half the mass of uranium—along with other lighter elements.[19] [20] This experimental result, initially puzzling as it contradicted prevailing transmutation theories, was chemically verified by Hahn and Strassmann, who ruled out contamination and confirmed the anomalous lighter isotopes through repeated fractional crystallization and spectroscopic analysis.[19] Physicists Lise Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch provided the theoretical explanation in early 1939, proposing that the uranium nucleus deformed and split into two fragments upon neutron absorption, releasing roughly 200 million electron volts of energy per fission event and 2-3 additional neutrons, enabling potential chain reactions.[19] This fission process in uranium-235, the rare fissile isotope comprising 0.72% of natural uranium, marked the foundational scientific breakthrough for harnessing nuclear energy, as the neutron multiplication factor could sustain exponential reactions under critical mass conditions.[20] Leo Szilard, who had patented the concept of a neutron chain reaction in 1934, recognized the military implications of fission and, in collaboration with Enrico Fermi, pursued experimental validation using uranium as fuel.[21] Their efforts culminated in the Einstein–Szilard letter of August 2, 1939, drafted by Szilard and signed by Albert Einstein, which warned President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the potential for "extremely powerful bombs" from uranium chain reactions and the risk of German development, urging U.S. acceleration of fission research and uranium stockpiling.[22] This prompted the establishment of the Advisory Committee on Uranium under Lyman Briggs, followed by intensified work at Columbia University where Fermi and Szilard demonstrated uranium's neutron multiplication in 1940-1941.[21] Concurrently, Glenn Seaborg's team at Berkeley isolated plutonium-239 in December 1940 by bombarding uranium-238 with deuterons, identifying it as a synthetic fissile isotope with properties suitable for chain reactions, produced via neutron capture in reactors.[23] The Manhattan Project, formally authorized in June 1942 under Brigadier General Leslie Groves with J. Robert Oppenheimer directing scientific efforts, focused on producing kilogram quantities of fissile material for atomic bombs, directly advancing nuclear fuel technologies.[23] At Oak Ridge, Tennessee (Clinton Engineer Works), uranium enrichment scaled to separate U-235 from U-238 using three parallel methods: electromagnetic isotope separation at Y-12 (producing calutrons that achieved up to 80% enrichment), gaseous diffusion at K-25 (employing uranium hexafluoride across thousands of porous barriers), and liquid thermal diffusion at S-50, collectively yielding about 64 kg of weapons-grade U-235 (>90% enriched) by July 1945.[24] Plutonium production occurred at Hanford, Washington, where uranium fuel rods—natural uranium metal or oxide—were irradiated in graphite-moderated reactors to transmute U-238 into Pu-239 via beta decay, followed by chemical separation using bismuth phosphate processes to isolate multi-kilogram quantities of weapons-grade plutonium (with low Pu-240 content to minimize predetonation).[25] The project's pivotal demonstration came on December 2, 1942, when Fermi's Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1), a subcritical assembly of 40 tons of natural uranium metal and oxide lumps interspersed with 6 tons of graphite moderator under the University of Chicago's Stagg Field squash court, achieved the world's first controlled, self-sustaining chain reaction at a power level of 0.5 watts, validating reactor design for fissile production without meltdown.[26] These innovations in fuel fabrication, enrichment, and reactor irradiation established the core processes for generating and handling nuclear fuels, transitioning from scientific curiosity to industrial-scale fissile material output exceeding 100 kg combined by mid-1945.[25]Post-War Commercialization and Proliferation

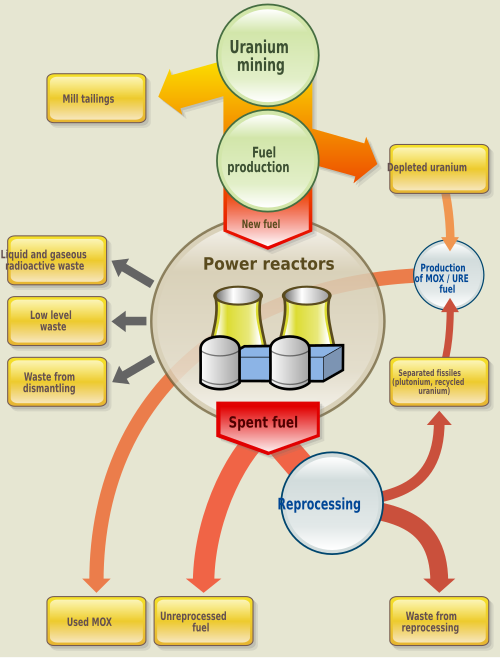

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 established a U.S. government monopoly on nuclear technology development, initially focused on military applications from the Manhattan Project.[27] This framework prioritized fissile material production for weapons, with sites like Hanford and Oak Ridge scaling up uranium enrichment and plutonium production using gaseous diffusion and reactors fueled by natural uranium.[20] The 1954 amendments to the Act permitted private industry involvement in civilian nuclear power, enabling the commercialization of nuclear fuel fabrication for electricity generation.[27] President Dwight D. Eisenhower's 1953 "Atoms for Peace" address proposed international cooperation on peaceful nuclear uses, leading to the creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 1957 to promote safeguards and technology sharing.[28] This program declassified reactor designs and facilitated exports of enriched uranium fuel and know-how, accelerating global adoption of light-water and gas-cooled reactor technologies requiring specific fuel forms like uranium oxide pellets.[29] However, the dual-use nature of the nuclear fuel cycle—enrichment for low-enriched uranium (LEU) in power reactors versus highly enriched uranium (HEU) for bombs—raised proliferation risks, as recipient nations gained expertise in separating fissile isotopes.[28][29] Commercial milestones included the UK's Calder Hall reactor, operational in 1956, which used natural uranium metal fuel in Magnox cladding for graphite-moderated power production.[30] In the United States, the Shippingport reactor achieved full power in 1957, fueled by 3-4% enriched uranium oxide assemblies in a pressurized water design, demonstrating scalable fuel behavior for baseload electricity.[31] These developments spurred industrial fuel supply chains, with U.S. firms like Westinghouse fabricating assemblies from enriched uranium produced at government facilities, totaling over 1,000 metric tons of LEU annually by the early 1960s.[20] Proliferation extended beyond the wartime powers as Atoms for Peace enabled bilateral agreements; France received U.S. assistance for its Marcoule reactors in 1956, developing indigenous plutonium reprocessing by 1962 to support both power and its 1960 nuclear test.[28] The Soviet Union independently commercialized VVER reactors with enriched uranium fuel by 1954 at Obninsk, while exporting RBMK designs requiring similar fuel cycles to allies like East Germany.[20] Canada pursued heavy-water CANDU reactors using natural uranium bundles from 1940s research, achieving commercial operation at NPD in 1962 without enrichment dependence, though this pathway still posed proliferation challenges via potential plutonium extraction.[30] By the 1970s, non-NPT states like India utilized imported heavy-water technology to produce weapons-grade plutonium from CIRUS reactor fuel in 1974, underscoring how commercial fuel pathways enabled covert diversion.[28]Nuclear Fuel Cycle

Front-End: Uranium Mining, Enrichment, and Fabrication

The front end of the nuclear fuel cycle involves the extraction, processing, and preparation of uranium for use in reactors, beginning with mining and culminating in the production of fuel assemblies. This phase ensures the supply of low-enriched uranium (LEU) tailored to reactor specifications, typically achieving 3-5% U-235 enrichment for light-water reactors. Global uranium resources, estimated at sufficient levels to support nuclear expansion through at least 2050 based on identified recoverable resources under current technologies, underpin this process, though exploration and investment are required to meet rising demand.[32][33] Uranium mining extracts ore containing typically 0.1-0.2% uranium, primarily as U3O8 (yellowcake) concentrate after milling. Methods include open-pit and underground mining for higher-grade deposits and in-situ recovery (ISR), which involves injecting leaching solutions into aquifers to dissolve uranium without surface excavation; ISR accounted for the majority of global production by 2024 due to its lower costs and environmental footprint compared to conventional methods. In 2024, world uranium mine production exceeded levels from prior years, with over 60% originating from ten major mines in Kazakhstan, Canada, Namibia, and Australia, reflecting concentrated supply amid geopolitical dependencies.[34][35] For instance, U.S. production reached 677,000 pounds of U3O8 in 2024, primarily via ISR in Wyoming and Utah, marking a rebound from near-zero levels in previous years.[36] Following mining and milling, uranium concentrate undergoes conversion to uranium hexafluoride (UF6) gas, enabling enrichment to separate the fissile isotope U-235 (0.7% in natural uranium) from U-238. The dominant modern method is gas centrifugation, which spins UF6 in high-speed rotors to exploit the slight mass difference, concentrating lighter U-235 molecules toward the center for collection; this replaced energy-intensive gaseous diffusion plants, which historically used porous barriers for isotopic separation but are now largely decommissioned due to higher electricity demands—centrifuges require about 50 times less energy per separative work unit (SWU). Enrichment facilities, such as those operated under strict safeguards, produce LEU tails with depleted uranium (0.2-0.3% U-235) as byproduct; global capacity in 2024 centered in Russia, Europe, and the U.S., with centrifuge cascades achieving tails assays optimized for economic efficiency.[37][38][4] Fuel fabrication converts enriched UF6 to uranium dioxide (UO2) powder via precipitation and calcination, followed by pressing into green pellets, sintering at high temperatures (around 1700°C) to achieve dense ceramic form with densities exceeding 95% theoretical, and grinding for uniformity. These pellets, typically 8-10 mm in diameter and 10-15 mm long, are loaded into zirconium alloy cladding tubes (e.g., Zircaloy-4) to form fuel rods, which are then bundled into assemblies—such as 17x17 arrays for pressurized water reactors—ensuring precise spacing with spacers and end fittings for coolant flow. The process demands stringent quality controls to minimize defects like cracking, with fabrication yields approaching 99% in advanced facilities; UO2's chemical stability and high melting point (over 2800°C) make it ideal for withstanding reactor conditions.[39][3][40] Final assemblies undergo inspection for dimensional accuracy and isotopic content before shipment to reactors, completing the front-end cycle.[41]In-Reactor Fuel Behavior and Energy Extraction

In nuclear reactors, energy extraction from fuel occurs via controlled fission chain reactions of fissile nuclides such as uranium-235 and plutonium-239, with each fission event releasing approximately 200 MeV, of which roughly 85% manifests as prompt heat deposited within the fuel lattice through the thermalization of fission fragment kinetic energy and neutron slowdown.[1] This heat generates radial temperature gradients in fuel pellets, with centerline temperatures in uranium dioxide (UO₂) typically ranging from 1000–1500°C under nominal light water reactor (LWR) conditions at linear heat rates of 15–20 kW/m, while surface temperatures remain below 400°C to maintain cladding integrity.[42] The extracted energy is transferred conductively through the fuel, gap, and cladding to the coolant, enabling steam generation for electricity production, with overall thermal efficiency around 33–35% in pressurized water reactors (PWRs). Burnup serves as the primary metric for quantifying energy extraction, defined as the integral of fission energy per unit initial heavy metal mass, commonly in gigawatt-days per metric ton of heavy metal (GWd/tHM); contemporary LWR fuels routinely achieve average discharge burnups of 50–60 GWd/tHM, reflecting improved utilization compared to earlier levels below 40 GWd/tHM.[43] [44] Higher burnups correlate with reduced fresh fuel requirements and longer cycle lengths but induce progressive degradation, including a 20–30% decline in UO₂ thermal conductivity due to phonon scattering by fission products and defects, which elevates centerline temperatures by up to 100–200°C at equivalent power.[45] Irradiation initially causes densification in sintered UO₂ pellets, reducing volume by 0.5–2% at burnups below 5 GWd/tHM via pore closure and migration, followed by swelling from solid fission product incorporation (yielding ~0.7% volume increase per 1% atomic burnup) and gaseous swelling from xenon and krypton bubbles, at rates of 0.4–0.7% per 10 MWd/kg UO₂ under steady-state conditions.[45] At higher burnups exceeding 40–50 GWd/tHM, a porous high-burnup structure (HBS) forms in the pellet periphery, featuring sub-micron grains and 10–15% porosity from recrystallization and gas retention, which minimally affects bulk swelling up to 75 GWd/tHM but locally impairs heat conduction.[45] Fission gas release (FGR) fractions remain low (<1–3%) during normal operation via diffusion and intergranular precipitation, though bursts up to 10–50% can occur during power ramps or annealing transients above 1000–1100°C, driven by bubble interlinkage and grain boundary saturation.[45] [46] Pellet-cladding interaction (PCI) emerges as fuel swells and the initial gap closes (typically by 40–45 GWd/tHM), imposing hoop stresses on the cladding up to 200–250 MPa during rapid power increases, compounded by corrosive fission products like iodine that promote stress corrosion cracking (SCC) in zirconium alloys.[47] Mitigation strategies include operational ramp limits (e.g., <5% power increase per hour) and fuel designs with annular pellets or lubricants to accommodate differential expansion, ensuring failure probabilities below 10⁻⁵ per rod-cycle.[45] Overall, these behaviors are modeled using codes like FRAPCON or BISON, validated against in-pile tests, to predict performance limits and maintain safety margins against melting (UO₂ at ~2800°C) or excessive rod growth.[48]Back-End: Spent Fuel Reprocessing, Storage, and Waste Management

Spent nuclear fuel, removed from reactors after typical burnups of 40-60 GWd/tU, consists of approximately 95-96% uranium (primarily U-238 with residual U-235), 1% plutonium isotopes, 3-4% fission products, and minor actinides such as americium and curium.[8] This composition renders the fuel intensely radioactive due to fission products and actinides, generating significant decay heat initially exceeding 10 kW per metric ton.[49] Management begins with cooling to dissipate heat and reduce short-lived isotopes' activity. Reprocessing separates reusable uranium and plutonium from waste via the PUREX process, involving dissolution in nitric acid followed by solvent extraction with tributyl phosphate to recover over 99% of fissile materials.[8] Commercial operations occur in France (La Hague facility processes ~1,100 tonnes annually), Russia, China, and Japan, enabling fuel recycling that reduces high-level waste volume by a factor of 5 and long-term radiotoxicity by 10 compared to direct disposal.[50] [8] However, the separation of weapons-usable plutonium raises proliferation risks, as evidenced by historical diversions and policy restrictions; the U.S. ceased commercial reprocessing in 1977 citing such concerns, though technical safeguards like IAEA monitoring mitigate but do not eliminate risks.[51] [52] Without reprocessing, or post-reprocessing, spent fuel undergoes interim storage. Initial wet storage in reactor pools provides shielding and cooling via circulated water, accommodating assemblies for 5-10 years until decay heat drops below 2 kW/t.[53] Subsequent dry cask storage employs sealed metal canisters within concrete or steel overpacks, relying on passive air convection for cooling; over 80,000 tonnes of U.S. spent fuel are stored this way at reactor sites, with systems licensed for 60+ years under NRC oversight demonstrating no significant releases.[54] [55] High-level waste—either vitrified reprocessing residues or intact spent fuel—requires isolation due to long-lived isotopes like plutonium-239 (half-life 24,100 years). Deep geological repositories, sited in stable formations 300-1,000 meters underground, encapsulate waste in corrosion-resistant canisters surrounded by bentonite buffers to contain radionuclides for millennia. Finland's Onkalo repository, operational from 2025, will dispose of 6,500 tonnes in crystalline bedrock, while Sweden's follows suit; the U.S. Waste Isolation Pilot Plant handles transuranic waste but not spent fuel, with Yucca Mountain stalled by political opposition despite geological suitability.[56] [57] Reprocessing minimizes repository needs by recycling actinides, though direct disposal of spent fuel as waste—practiced in the once-through cycles of the U.S., Sweden (interim), and others—avoids proliferation but increases disposal volume.[8][58]Primary Types of Fission Fuels

Enriched Uranium Oxide (UOX) Fuels

Enriched uranium oxide (UOX) fuel, primarily in the form of uranium dioxide (UO₂), serves as the standard fissile material for most commercial light water reactors (LWRs), including pressurized water reactors (PWRs) and boiling water reactors (BWRs). The fuel is fabricated from uranium enriched to 3-5% uranium-235 (²³⁵U) by weight, significantly higher than the 0.7% found in natural uranium, to sustain a controlled chain reaction in thermal neutron spectra moderated by light water.[38][37][59] This enrichment level balances neutron economy with proliferation resistance, as concentrations below 20% ²³⁵U are classified as low-enriched uranium (LEU).[60] The fabrication process for UOX begins with the chemical conversion of enriched uranium hexafluoride (UF₆) gas to UO₂ powder through hydrolysis and reduction steps, yielding a fine black powder with particle sizes typically around 0.1-1 micrometer. This powder is then mixed with binders, pressed into cylindrical pellets (about 8-10 mm in diameter and 10-15 mm long) under high pressure to achieve green densities of 50-60% theoretical, and sintered at temperatures of 1400-1700°C in a reducing atmosphere to densify to over 95% of theoretical density, minimizing porosity for optimal thermal conductivity and fission gas retention.[61] The sintered pellets exhibit thermophysical properties such as a thermal conductivity of approximately 2-5 W/m·K at operating temperatures and a melting point exceeding 2800°C, enabling high-temperature operation while resisting clad breach under normal conditions.[18] Pellets are stacked into zirconium alloy cladding tubes (e.g., Zircaloy-4 or optimized variants with 1-2% niobium for improved corrosion resistance), sealed with end plugs via welding, and assembled into fuel rods about 4 meters long. Multiple rods form fuel assemblies, typically 17x17 arrays for PWRs holding 264 rods and 21,000-25,000 pellets per assembly, with spacers to maintain geometry and control coolant flow.[59] In reactor cores, UOX achieves average discharge burnups of 40-60 gigawatt-days per metric ton (GWd/t), with peak rod burnups reaching 60-70 GWd/t in modern designs, reflecting efficient utilization of ²³⁵U and incidental plutonium breeding before refueling cycles of 12-24 months.[59][62] UOX's performance is characterized by stable fission product buildup, including cesium, iodine, and xenon, which influence reactivity and cladding integrity; high-burnup fuels show increased pellet-clad interaction due to fuel swelling but benefit from advanced cladding to extend operational margins. While UOX dominates global LWR operations—powering over 90% of nuclear electricity generation—its reliance on enriched uranium ties it to front-end cycle costs, and spent fuel contains recoverable plutonium alongside actinides complicating long-term storage.[59][59]Mixed Oxide (MOX) and Plutonium Fuels

Mixed oxide (MOX) fuel consists of a physical blend of plutonium dioxide (PuO2) and uranium dioxide (UO2), typically incorporating 5-7% PuO2 by weight for use in light water reactors (LWRs), with the uranium component often derived from depleted uranium tails or reprocessed uranium.[63] This composition enables the recycling of plutonium extracted via aqueous reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel, primarily through the PUREX process, which separates plutonium alongside uranium from fission products and minor actinides.[8] MOX fabrication involves milling PuO2 and UO2 powders, mixing them homogeneously, pressing into green pellets, and sintering at high temperatures (around 1700°C) to achieve densification comparable to standard UO2 fuel, followed by grinding and loading into zircaloy cladding.[64] Facilities for industrial-scale MOX production are limited, with France's Melox plant (operated by Orano since 1995) producing up to 195 metric tons annually, sufficient to fuel about 25-30 LWRs as a partial substitute for enriched uranium oxide (UOX) assemblies.[65] Plutonium in MOX derives almost exclusively from civilian reprocessing, yielding "reactor-grade" material characterized by an isotopic vector of approximately 50-70% 239Pu, 20-30% 240Pu, and higher fractions of 241Pu and 242Pu compared to weapons-grade plutonium, which exceeds 93% 239Pu and contains less than 7% 240Pu to minimize spontaneous fission and predetonation risks in simple implosion devices.[66] Reactor-grade plutonium remains fissile and capable of sustaining chain reactions in thermal or fast spectrum reactors, but its higher 240Pu content increases neutron emissions, complicating weaponization by raising the probability of premature fission initiation, though designs can achieve yields of 1-20 kilotons with advanced implosion techniques.[67] Pure plutonium fuels, such as metallic plutonium or Pu-Zr alloys, have been tested primarily in experimental fast breeder reactors like Russia's BN-350 and BN-600, where they enable higher breeding ratios due to the absence of uranium's parasitic neutron absorption, but commercial deployment remains negligible outside research contexts owing to corrosion, swelling under irradiation, and fabrication complexities.[64] In operational use, MOX fuel assemblies are loaded into LWR cores alongside UOX, often comprising up to one-third of the core to maintain criticality, with demonstrated burnups exceeding 45 GWd/t in French pressurized water reactors (PWRs) since the 1980s, comparable to or surpassing UOX performance despite slightly lower thermal conductivity and higher fission gas release.[63] France generates about 10% of its nuclear electricity from MOX in 20 PWRs, recycling over 10 tonnes of plutonium annually, while Japan's program has utilized imported MOX fabricated in Europe for reactors like those at Fukushima prior to 2011, though domestic J-MOX fabrication at Rokkasho has faced repeated delays and produced minimal output as of 2023.[63] Advantages include extending uranium resources by a factor of up to 30 through multi-recycling in fast reactors and reducing the long-term radiotoxicity of high-level waste by fissioning plutonium and associated minor actinides, with spent MOX exhibiting threefold lower eventual decay heat compared to once-through UOX cycles assuming direct disposal.[68] However, MOX incurs 20-30% higher fabrication costs due to specialized handling for alpha-emitting plutonium, generates more heat and neutrons during operation (necessitating adjusted control strategies), and poses proliferation risks from separated plutonium stocks, which total over 300 tonnes globally in civilian programs as of 2023, vulnerable to diversion despite safeguards.[69][70] The U.S. explored MOX for disposing of 34 tonnes of weapons-grade plutonium under a 2000 bilateral agreement with Russia, planning irradiation in PWRs to render it reactor-grade and irretrievable without reprocessing, but the program was terminated in 2018 after $10 billion spent, shifting to dilute-and-dispose methods due to cost overruns and technical hurdles at the Mixed Oxide Fuel Fabrication Facility in South Carolina.[71] In fast reactors, MOX supports closed fuel cycles with breeding ratios above unity, as demonstrated in Russia's BN-800 operational since 2016 using reactor-grade plutonium-derived MOX, which achieves equilibrium cores with up to 20% PuO2 loadings and transuranic destruction efficiencies exceeding 90% over multiple recycles.[72] Proliferation-resistant features, such as intentional mixing with high-240Pu fuels or embedding in proliferation-resistant matrices, have been proposed but not widely implemented, as empirical tests confirm that even reactor-grade plutonium enables nuclear explosives with yields sufficient for strategic deterrence, underscoring the need for stringent IAEA monitoring of all separated material.[73]Thorium-Based Fuels

Thorium-based fuels primarily employ thorium-232 (^232Th), a naturally occurring fertile isotope, which undergoes neutron capture in a reactor to produce fissile uranium-233 (^233U) via the sequence ^232Th + n → ^233Th (β⁻ decay, half-life 22 minutes) → ^233Pa (β⁻ decay, half-life 27 days) → ^233U.[74] [75] This breeding process enables a thorium-uranium fuel cycle distinct from the uranium-plutonium cycle, requiring an initial fissile material such as ^235U or plutonium-239 to sustain neutron flux for conversion.[74] ^233U exhibits a high fission cross-section in thermal neutron spectra, supporting potential breeding ratios exceeding 1.0 in optimized designs like molten salt reactors or heavy-water moderators.[76] Thorium fuels are typically fabricated as thorium dioxide (ThO₂) pellets, often blended with fissile uranium or plutonium oxides in seed-blanket configurations for light-water reactors (LWRs) or as standalone fertile blankets in breeder systems.[74] These fuels offer advantages including greater natural abundance—global thorium resources estimated at 6.4 million tonnes recoverable versus 5.5 million for uranium—and reduced production of transuranic actinides, yielding waste with shorter radiotoxicity decay times (approximately 300 years versus 10,000+ for uranium cycles).[74] [77] Proliferation resistance arises from ^232U contamination in bred ^233U, which decays (half-life 68.9 years) to ^208Tl emitting intense 2.6 MeV gamma rays, complicating weaponization without specialized handling.[74] [76] However, challenges include the need for online reprocessing to separate ^233Pa (to prevent neutron capture losses) in high-breeding scenarios, corrosion issues in molten-salt implementations, and higher upfront gamma shielding requirements during fabrication due to ^232Th decay daughters.[77] [78] Historical experiments include the U.S. Molten Salt Reactor Experiment (MSRE) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, operational from 1965 to 1969, which demonstrated ^233U-fueled thorium cycles at 7.4 MWth with fuel salts containing 70% LiF-BeF₂-ThF₄-UF₄, achieving stable operation but highlighting material corrosion and fission product removal needs.[79] The Shippingport Light Water Breeder Reactor core (1977–1982) tested a ThO₂-UO₂ seed-blanket assembly, producing 2.1% more fissile material than consumed over 26,000 effective full-power hours.[74] India's Kakrapar-1 reactor loaded ThO₂ bundles in 2020 alongside natural uranium, extracting ^233U experimentally, as part of a three-stage program leveraging domestic thorium reserves exceeding 225,000 tonnes.[74] Recent developments emphasize advanced reactor integration. China's 2 MWth thorium-fueled molten salt reactor (TMSR-LF1) in Wuwei achieved criticality in 2021 and performed continuous refueling without shutdown in April 2025, validating salt chemistry and breeding efficiency.[80] Plans for a 10 MWe demonstration thorium molten-salt reactor in the Gobi Desert are slated for construction starting in 2025.[81] In the U.S., Clean Core Thorium Energy's ANEEL fuel—a ThO₂-UO₂ composite with up to 20% fissile content—underwent irradiation testing in Idaho National Laboratory's Advanced Test Reactor in 2024, targeting LWR compatibility and reduced waste.[82] India's Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor at Kalpakkam, core-loaded in 2024, incorporates thorium blankets to breed ^233U, aiming for commissioning by 2026 en route to advanced heavy-water reactors.[83] Despite these advances, commercial deployment lags due to established uranium infrastructure, regulatory hurdles for reprocessing, and the absence of large-scale ^233U production facilities.[78] [77]Metal and Non-Oxide Ceramic Fuels