Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

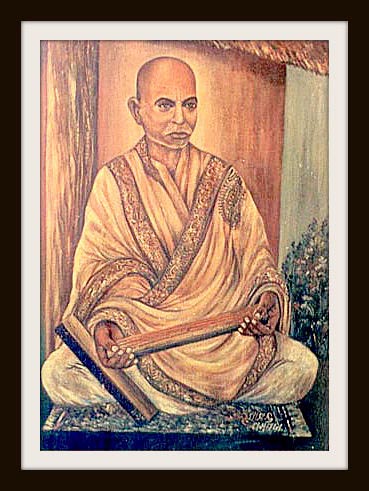

Pathani Samanta

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

Pathani Samanta[a] better known as Mahamahopadhyaya Chandrasekhara Singha Harichandana Mahapatra Samanta,[b] was an Indian astronomer, mathematician and scholar who measured the distance from the Earth to the Sun with a bamboo pipe, and traditional instruments. He was born on 13 December 1835 in Purnimanta Pousha Krishna Ashtami, and died on 11 June 1904 in Purnimanta Adhika Jyeshtha Krishna Trayodashi.

Key Information

His research and observations were compiled into a book called Siddhanta Darpana, which was written in both Sanskrit and the Odia script. He earned the Mahamahopadhyaya Award in 1893, for his usage of traditional instruments for astronomical observations.[1]

Biography

[edit]This section is written like a story. (February 2020) |

Samanta was born in the princely state of Khandpara, in the Nayagarh district of the Indian state of Odisha.[2] He was the son of Samanta Syamabandhu Singha and Bishnumali Devi. He was born into a royal family.

The legend depicted on the walls of the Pathani Samanta Planetarium in Bhubaneswar states that he was born to a royal couple the loss of many children, leaving them yearning for a healthy child. Hence, soon after his birth, he was given away in adoption to a Muslim fakir to ward off the evil eye, a belief that was strongly prevalent at the time. In remembrance of the fakir and to ward off bad omens, the couple nicknamed their son 'Pathani'.

He went on to study Sanskrit, and later researched traditional Indian astronomy.

During his youth time, Samanta measured the length of the shadows throughout the day by using bamboo and wood to create measuring instruments, which he called mana yantra. He also measured time by using his version of a sundial.[3]

He was the only Indian astronomer who discovered all three irregularities of the moon independently of European astronomers, which were unknown to ancient Indian astronomers.[4] He continued to teach and attracted pupils worldwide despite his persistent health problems and insomnia. On June 11, 1904, he died suddenly from fever and infection.[3]

Education

[edit]He was home-schooled by his father, who introduced him to the joys of night star-gazing, and later by a Brahmin teacher, who gave him a basic education in both Odia and Sanskrit. By the age of 15, he had become a self-learner, referring to the books available in the royal library. Samanta was a voracious reader and devoured classical treatises like Lilavati, Bijaganita, Jyotisha, Siddhanta, Vyakarana, and Kavya. It was during this time that he pursued mathematics and traditional astronomy, and started matching predictions made by ancient Indian mathematician-astronomers such as Aryabhatta - 1(476 CE), Varahamihira (503 CE), Brahmagupta (598 CE) and Bhaskara – II (1114 CE) and others, with real observations of celestial objects in the night sky. Although traditional Indian astronomy had veered more toward astrology, focusing more on future predictions based on planetary positions and the preparation of auspicious almanacs for rituals, Samanta focused minutely on the mathematical calculations and observational facts that went into these predictions. When he found discrepancies, he designed his own instruments to measure the phenomena, using everyday materials such as wood and bamboo!

Instrument maker

[edit]Samanta was a self-taught astronomer and learned by reading the books available at the Royal Library until age 15. During his research, Samanta designed many of his instruments by using everyday materials such as wooden sticks and bamboo.[4] After studying mathematics and traditional astronomy he used his knowledge to match predictions made by ancient Indian mathematicians and astronomers such as Aryabhata, Varahamihira, and Brahmagupta.

He carried out research in measurements using only a bamboo pipe and two wooden sticks.[5] His findings were recorded in his book titled Siddhanta Darpana and were mentioned in the European and American press in 1899. Samanta's calculations were eventually used in the preparation of almanacs in Odisha.

Working With Wood & Bamboo

[edit]The treatises Samanta was referring to had only clues to the observational devices used, so he decided to make his own measuring instruments made of locally available bamboo and wood. They used basic geometry and trigonometry to calculate distance, height, and time. There are many local tales of Samanta measuring the height at which birds fly, finding the height of trees, and persons using the length of shadows and calculating the distance and height of mountains from his fixed location using an instrument he invented called mana yantra.

He used his own versions of the sundial and imprsundialater clocks to measure time. Here are a few sketches of these instruments from the article published by Prof P.C. Naik and Prof. L Satpathy in the Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India (1998).

Awards & Recognition

[edit]Samanta received the title "Harichandan Mahapatra" from the Gajapati King of Puri in 1870, and the revered Jagannath Temple in Puri still adheres to the calendar rules he suggested for carrying out its ceremonies. The British government, which ruled India during Samanta's lifetime, conferred upon him the title of 'Mahamahopadhyay' in 1893 and awarded him a pension of Rs 50 per month for his contributions to astronomy after he correctly predicted the time and place of a solar eclipse that was visible only in Britain.

Personal life and legacy

[edit]Samanta married Sita Devi, the daughter of King Anugul, in 1857 in a rather dramatic way after the bride's family rejected the alliance on the couple's wedding day because Samanta didn't look princely enough, according to his family history, which was written by his grandson Raghunath Singh Samanta and published in the book "Pathani Samanta Jeebani Darpana". He reportedly won over the bride's family at the wedding with his faultless sloka recitation.

Govt of India have issued a commemorative postage stamp on Samanta Chandra Sekhar in the year 2001[6]. Odisha has kept his legacy relevant by displaying his work in the state museum, naming the planetarium in Bhubaneswar after him; and dedicating educational institutions, scholarships, and amateur astronomy clubs to his memory. Annual Samanta Chandra Sekhar Award has been instituted by the Odisha Bigyan Academy, in the year 1987, to recognise outstanding scientists of Odisha-origin, working inside or outside Odisha [7]. Similarly, Samanta Chandrasekhar Jyotirbigyani Sanman (SCJS) has also been instituted by the Samanta Chandrasekhar Amateur Astronomers Association (SCAAA). Dr Nikhil Mohan Pattnaik, Dr Prahallad Chandra Naik and Dr Ananda Hota have been conferred this SCJS award in its inaugural year 2018 which was also the silver jubilee year of SCAAA. Every year, since 2007, Tata Steel, in collaboration with the Pathani Samanta Planetarium under the Science & Technology Department of the Government of Odisha, organises the Young Astronomer Talent Search (YATS)[8]. High school students from each and every district of Odisha participate which can make the total number of participants reach up to 76,600 in a single year[9]. At the final stage of YATS, around the birth anniversary of Pathani Samanta (13th December), winners are awarded at a function in the state capital Bhubaneswar, usually by the Chief Minister of the state, and a few reputed scientists or technologists are invited to inspire the young students for a career in astronomy and space-science[10].

Astronomers and astrophysicists both in India and beyond have praised his work, earning him the moniker "Indian Tycho." However, the general public is mostly unaware of this brilliant astronomer who observed the universe with only the naked eye, as well as of the incredible scientific advances he accomplished with only a few pieces of bamboo and wood and the sheer force of his brilliance. He deserves to be celebrated just like Aryabhatta, Bhaskara, and others - probably as the last torch bearer of the Indian traditional astronomy.

Notes

[edit]- ^ ପଠାଣି ସାମନ୍ତ; Odia pronunciation: [pɔntʰani samoːntoː]

- ^ ମହାମହୋପାଧ୍ୟାୟ ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଶେଖର ସିଂହ ହରିଚନ୍ଦନ ମହାପାତ୍ର ସାମନ୍ତ; Odia pronunciation: [mɔhamɔhoːpadʰjajɒ t͜ʃɔndroseːkʰɔr siŋho horit͜ʃɔndoːn mɔhapatroː samoːntoː]

References

[edit]- ^ Naik, P. C.; Satpathy, L. (1998). "Samanta Chandra Sekhar : The great naked eye astronomer". Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India. 26: 33–49. Bibcode:1998BASI...26...33N.

- ^ "EMINENT PERSONALITY".

- ^ a b Katti, Madhuri. "Chandrasekhar Samanta: India's Eye in the Sky". Live History India. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ a b Panda, Bipin Bihari (2000). "PATHANI SAMANTA AND HIS THEORY OF PLANETARY MOTION" (PDF).

- ^ "Samanta Chandrasekhar". Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- ^ "Postage Stamps:: Postage Stamps,Stamp issue calender 2014, Paper postage, Commemorative and definitive stamps, Service Postage Stamps, Philately Offices, Philatelic Bureaux and counters, Mint stamps". postagestamps.gov.in. Archived from the original on 2025-08-09. Retrieved 2025-12-02.

- ^ "Samanta Chandra Sekhar Award – Odisha Bigyan Academy". Retrieved 2025-12-02.

- ^ Services, Hungama Digital. "14th Edition of Tata Steel Young Astronomer Talent Search | YATS 2020". www.tatasteel.com. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

- ^ Services, Hungama Digital. "Odisha Science and Technology Minister Felicitates Tata Steel Young Astronomer Talent Search Winners 2025". www.tatasteel.com. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

- ^ "Odisha CM Naveen Patnaik felicitates winners of 12th Edition of Tata Steel YATS – Odisha Diary, Latest Odisha News, Breaking News Odisha". orissadiary.com. Archived from the original on 2024-06-20. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

Bibliography

[edit]- Satpathy, L., ed. (2003). "Samanta Chandra Sekhar and his Contributions to Ancient Indian Astronomy.". Ancient Indian Astronomy and Contributions of Samanta Chandra Sekhar. ISBN 9788173194320.

- Sriram, M. S.; Ramasubramanian, K.; Srinivas, M. D. (2002). "Samanta Chandra Sekhara and His Treatise Siddhantadarpana.". 500 years of Tantrasangraha: a landmark in the history of astronomy. p. 127. ISBN 9788179860090.

Pathani Samanta

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Birth and Family Background

Pathani Samanta, originally named Chandra Sekhar Samanta, was born on 13 December 1835 in Khandapara, the capital of the princely state of Khandapara in present-day Odisha, India.[1] His birth occurred during a period when Odisha was under British colonial influence, and the region was characterized by a blend of traditional Hindu scholarship and local princely governance.[5] He was the son of Samanta Syamabandhu Singha, a zamindar and scholar knowledgeable in Sanskrit literature and Jyotisha (Indian astronomy and astrology), and his wife Bishnumali Devi (also referred to as Vishnumali Devi).[3] The family hailed from the royal lineage of the Khandapara estate, which maintained a longstanding tradition of intellectual pursuits in classical Indian sciences, including the maintenance of family libraries stocked with palm-leaf manuscripts on Jyotisha and related disciplines.[1] Despite their noble status, the family faced financial hardships in the 19th century, which limited access to external resources but preserved their cultural heritage.[1] The nickname "Pathani," by which he became widely known, originated from a protective ritual performed shortly after his birth. Following the deaths of his parents' first two children in infancy, the couple sought to shield the newborn from the evil eye by temporarily "adopting" him through a Muslim fakir in a symbolic ceremony; "Pathani" derives from "Pathan," referring to Afghan Muslims, in remembrance of this safeguard.[6] This practice reflected the syncretic cultural elements in 19th-century Odisha, where Hindu families occasionally incorporated folk rituals involving interfaith figures for protection.[3] Syamabandhu Singha's own engagement with Jyotisha, including the preparation of local almanacs, laid the foundation for his son's early exposure to astronomical concepts within the family's scholarly environment.[7]Childhood and Early Influences

Pathani Samanta, born Chandrasekhara Samanta in 1835 in the rural princely state of Khandapara in present-day Odisha, grew up in a zamindari household steeped in traditional Hindu customs and local superstitions. His family, part of the local royalty, had endured profound grief from the deaths of their first two children in infancy, which deeply influenced the household dynamics and led to heightened protective rituals to safeguard the newborn against perceived evil influences. This loss fostered a cautious and devoted family environment, where parents prioritized spiritual safeguards over material concerns, shaping young Chandrasekhara's early sense of vulnerability and resilience within the rural setting.[1][6] To counter the ominous pattern, shortly after his birth, the infant was symbolically adopted in a ritual by a Muslim fakir, a common superstitious practice in the region to ward off the evil eye and ensure the child's survival; in remembrance of this event, his parents nicknamed him "Pathani," meaning "of the Pathan" or fakir. This ceremony, rooted in syncretic local beliefs blending Hindu and folk Islamic elements, highlighted the pervasive role of superstitions in rural Odia life during the 19th century, where such adoptions were believed to transfer protective blessings. The family's scholarly background, with access to ancient manuscripts, further embedded him in a cultural milieu rich with oral traditions and ritualistic observances.[6][3] Samanta's initial curiosity about the cosmos was sparked in his early years through direct observation of the night sky in the unpolluted rural expanse of Khandapara, where celestial events like planetary positions and occasional eclipses captivated his attention. By age four, he reportedly identified Venus during twilight, demonstrating an innate fascination that drew him to gaze at stars and shadows, often measuring tree shadows to understand solar movements informally. These formative experiences, amid the zamindari's exposure to traditional Odia folklore and Sanskrit-influenced narratives, instilled a worldview blending wonder with the mystical interpretations prevalent in his community, setting the stage for his later pursuits without formal guidance at the time.[3][8]Self-Taught Education in Astronomy

Pathani Samanta received his initial education at home until the age of 12, under the guidance of his father, Samanta Syamabandhu Singha, and a Brahmin tutor named Ananda Khadenga. This homeschooling focused on foundational subjects such as basic Sanskrit, arithmetic, and grammar, laying the groundwork for his later intellectual pursuits.[6][9] By the age of 15, Samanta transitioned to self-directed study, drawing extensively from the royal library in Khandapara, which housed a collection of classical Indian texts. He immersed himself in key works like Lilavati for mathematics and Surya Siddhanta for astronomy, using these ancient treatises to build his understanding of celestial sciences without formal instruction. This independent approach allowed him to explore concepts systematically, relying on the library's resources to compensate for the absence of structured schooling.[6][2] Through rigorous independent experimentation, Samanta achieved mastery in trigonometry, geometry, and Jyotisha by his late teens, applying these disciplines to verify and refine theoretical principles. In his early 20s, he advanced to complex topics such as planetary motions, integrating his self-acquired knowledge to address discrepancies in traditional models. This phase marked his evolution from basic learner to proficient scholar, driven entirely by personal dedication and empirical validation.[6][9]Astronomical Contributions

Instrument Design and Construction

Pathani Samanta exemplified engineering ingenuity in 19th-century Odisha by designing and constructing astronomical instruments from locally sourced materials like wood, bamboo, bottle gourd shells, and occasional iron bowls, circumventing the scarcity of metal components and specialized craftsmen. These devices relied on simple yet precise mechanisms, drawing from his self-taught understanding of geometry to achieve reliable measurements without advanced technology.[1][3] Among his innovations, the Mana Yantra stands out as a versatile tool for trigonometric applications, comprising a straight wooden staff paired with a notched, pierced U-shaped cross-piece that allowed for accurate angle measurements in both celestial and terrestrial contexts, such as determining shadows, heights, and distances. Construction involved careful geometric alignments to ensure stability and accuracy, with components like staffs and discs calibrated against fixed references such as the Pole Star or known solar positions.[1][3] For timekeeping, Samanta created several sundial variants adapted to solar movements, including the Chapa Yantra—a semi-circular wooden dial with a gnomon aligned to the north celestial pole for half-day readings—and the Chakra Yantra, a full graduated disc centered on a vertical staff that tracked shadow progression across the day. These were tested iteratively against established traditional yantras to verify precision, emphasizing portability and ease of replication with everyday materials like bamboo frames and string tensions for adjustments. The Golardha Yantra, a hemispherical variant, further extended this approach by incorporating curved surfaces for equinox-specific alignments. Overall, his techniques prioritized empirical validation through repeated alignments with observable celestial markers, ensuring the instruments' functionality in resource-limited settings.[1][5][3]Key Observations and Predictions

Pathani Samanta conducted meticulous naked-eye observations of solar and lunar eclipses throughout his career, recording timings and visibility with high precision using traditional methods refined by his empirical data. These observations formed the basis for his eclipse prediction formulas, which demonstrated exceptional accuracy and were incorporated into Oriya almanacs that successfully forecasted celestial events for generations. One notable achievement was his precise prediction of the timing and visibility of a solar eclipse observable in remote regions, such as solar eclipses visible in Odisha and surrounding regions, showcasing the reliability of his traditional Indian astronomical techniques.[10] Through observations aided by his custom instruments like the Mana Yantra, Samanta independently identified the three principal irregularities in the Moon's motion—evection (Tungantara, max ≈2°40'), variation (Pakshika, max ≈38'), and annual equation (Digamsa, max ≈12")—which had been inadequately parameterized in earlier Indian works despite being recognized in European astronomy. He quantified these effects to refine lunar position calculations, enabling corrections that improved predictive accuracy for lunar phenomena. These discoveries highlighted the Moon's complex orbital dynamics and validated the potential of naked-eye astronomy when combined with rigorous geometric analysis.[1][10] Samanta systematically compared predictions from ancient Siddhanta texts, such as the Surya Siddhanta and Siddhanta Siromani, against his own observations, revealing cumulative errors in accumulated manuscripts due to transcriptional inaccuracies and outdated parameters over centuries. His analyses identified discrepancies in planetary longitudes up to several degrees in traditional almanacs, which he attributed to unaccounted anomalies and precession effects. By applying observational corrections, he reduced these errors to within half a degree, demonstrating how empirical verification could restore the integrity of classical Indian astronomy.[1][3] Employing geometric methods derived from shadow measurements and angular observations, Samanta calculated planetary positions by integrating mean motions with anomaly corrections, achieving alignments that matched visible sky events with minimal deviation. These techniques involved trigonometric computations using self-made graduated scales to determine longitudes and latitudes relative to fixed stars. Similarly, he estimated the Earth's diameter through geometric triangulation of zenith distances at different locations, underscoring the Earth's sphericity in his geocentric model.[3][10]Major Publications and Theories

Pathani Samanta's most significant scholarly contribution is his comprehensive astronomical treatise Siddhanta Darpana, composed in Sanskrit verses between 1869 and 1892 and published in 1899 from the Indian Depository in Calcutta.[10][1] This work, spanning 24 chapters and approximately 2,500 verses (with 2,184 original compositions by Samanta), systematically critiques and refines classical Indian astronomical texts such as the Surya Siddhanta and Siddhanta Siromani, addressing longstanding discrepancies in planetary calculations and almanac predictions.[10] An Odia-script edition followed, making the content more accessible to regional scholars.[11] Central to Siddhanta Darpana are Samanta's efforts to reconcile traditional geocentric models with empirical observations derived from naked-eye astronomy and rudimentary instruments. He introduced corrections for anomalies in celestial motions, such as the Moon's evection, variation, and annual equation, which had been overlooked or inaccurately parameterized in prior Siddhantic works, thereby enhancing the precision of positional predictions.[1] Additionally, Samanta revised parallax values—setting the solar parallax at 22 arcseconds and lunar at 56 minutes 28 seconds—to better align theoretical frameworks with recorded data, enabling more reliable computations of eclipses and planetary transits.[1] The treatise includes detailed ephemerides and tabular data for celestial positions, projected to remain accurate for up to 10,000 years, though practical applications focused on long-term almanac reliability.[10] Beyond Siddhanta Darpana, Samanta produced unpublished manuscripts on specialized topics, including advanced trigonometry for angular measurements and precise methods for eclipse calculations. These works emphasize empirical verification, with novel formulas for determining planetary longitudes (such as Tungantara, Pakshika, and Digamsa for the Moon) and timings of solar and lunar eclipses, which prioritized observational accuracy over rote adherence to ancient traditions.[10] Samanta's publications played a pivotal role in reviving positional astronomy within 19th-century India, bridging classical Siddhantic methodologies with refined observational practices at a time when Western influences were dominant. By correcting errors that caused significant deviations in contemporary almanacs—such as a 40-degree inaccuracy in Bengali calendars reduced to 0.5 degrees in his system—his theories restored credibility to indigenous astronomical traditions and influenced the development of modern Oriya almanacs still in use today.[1][10]Recognition and Legacy

Contemporary Awards and Honors

In 1870, Pathani Samanta was conferred the title of Harichandan Mahapatra by the Gajapati King of Puri in recognition of his astronomical services, particularly his contributions to calendar calculations used in temple rituals.[3] This honor underscored his growing reputation within local royal and religious circles for precise astronomical computations based on traditional Indian methods. Samanta's interactions with British colonial officials highlighted his expertise and earned him formal acknowledgment. He demonstrated his handmade instruments, such as the Yantra for measuring celestial positions, to British surveyors and administrators, showcasing the accuracy of his naked-eye observations in comparison to European tools.[5] In 1893, following an invitation from Viceroy Lord Lansdowne to Calcutta—which Samanta declined due to health reasons—a British emissary, Mr. Cook, visited him in Cuttack and awarded the prestigious title of Mahamahopadhyaya on behalf of the British government. This accolade, along with a monthly pension of Rs. 50, was granted specifically for his accurate predictions of solar eclipses, including one visible only in Britain, which aligned closely with Western calculations.[3][5] Local zamindari and princely support played a crucial role in enabling Samanta's work, including the setup of his personal observatory at Khandapada. Rulers such as the Raja of Manjusha Zamindari provided patronage, funding the construction of observation platforms and instrument fabrication using local materials like bamboo and wood. Additionally, kings from states like Athmallik and Mayurbhanj offered financial assistance for his research and publications, allowing him to maintain his observatory without reliance on colonial resources.[12][3]Posthumous Tributes and Influence

Following Pathani Samanta's death in 1904, his legacy has been honored through dedicated institutions in Odisha that preserve and promote his contributions to astronomy. The Pathani Samanta Planetarium in Bhubaneswar was established on January 8, 1990, by the Odisha Government's Department of Science and Technology, spanning five acres and featuring a 12-meter dome for educational shows on astronomy and space science.[13] As of May 2025, the planetarium has been reported to be in a state of neglect and poor maintenance, affecting visitor access.[14] Complementing this, the Pathani Samanta Museum in Khandapada, Nayagarh district, opened on 21 December 2016 as a facility housing rare artifacts used by Samanta, such as yantras, and attracts researchers studying indigenous observational techniques.[15] In 2023, replicas of six of his key instruments were exhibited in Bhubaneswar to educate the public on his self-made tools for celestial measurements.[16] The Odisha government has institutionalized annual support for aspiring scientists in his name, reflecting the foundational recognition he received during his lifetime for advancing traditional astronomy. The Pathani Samanta Mathematics Talent Scholarship, launched by the School and Mass Education Department, provides up to ₹5,000 annually to 300 meritorious students in Classes 11 and 12 from general, ST, SC, OBC/SEBC, and EBC categories who excel in mathematics—a core element of astronomical calculations—based on Board of Secondary Education results.[17] This program fosters talent in science education, aligning with Samanta's emphasis on precise computations without modern aids. Recent commemorations underscore his enduring relevance, including events on his birth anniversary, December 13, 2023, such as public tributes, quiz competitions, and night sky observation programs organized across Odisha to highlight his naked-eye predictions.[18] His work is integrated into educational initiatives like the Young Astronomer Talent Search (YATS), an annual competition since 2007 in collaboration with the planetarium, targeting Classes 6–10 students and drawing over 60,000 participants by 2018 to promote astronomy awareness.[19] Samanta's influence extends to inspiring indigenous science in India, positioning him as a symbol of self-reliant innovation against colonial-era dismissals of traditional knowledge systems. Scholars note his accurate solar distance calculations using bamboo-based yantras as a critique of Western scientific hegemony, emphasizing the validity of pre-colonial Indian methods in modern discourse.[20] Preservation efforts, including digitized images of his palm-leaf manuscripts like Siddhanta Darpana on platforms such as Wikimedia Commons, ensure accessibility, though comprehensive 2020s digital archives remain underdeveloped compared to his physical exhibits.[21]Personal Life

Marriage and Family

Pathani Samanta married Sita Devi, the daughter of the king of Angul, in 1857. The union was arranged within the local community but unfolded dramatically, with Samanta leading a grand procession to Angul after the bride's family initially rejected the alliance due to his unprincely appearance.[6][3] Following the marriage, Samanta fathered five sons and six daughters, of which two sons and four daughters died young, with only two daughters surviving to marry into other families. He supported his large family amid financial challenges as the Raja of Khandapara.[8][1] The couple resided in Khandapara, where Samanta balanced his estate management responsibilities with his immersive astronomical studies, often dedicating nights to observations at his home observatory.[1] Samanta's family contributed to safeguarding his scholarly legacy after his death, including the preservation of his manuscripts and instruments, some of which are now housed in institutions like the Odisha State Museum. His grandson, Raghunath Singh Samanta, documented these aspects in the biography Pathani Samanta Jeebani Darpana, ensuring the transmission of family records and artifacts.[5][6]Health Challenges and Death

Pathani Samanta endured chronic insomnia throughout his life, a direct consequence of his relentless late-night astronomical observations, which severely impacted his overall health.[6] These sleepless nights led to persistent digestive issues, including dyspepsia accompanied by colic, which became lifelong companions and contributed to his general frailty, particularly evident in his later years during the 1890s.[5] His family provided crucial support during periods of illness, caring for him amid his weakening condition.[6] Samanta's health deteriorated further in 1904 when he was struck by a severe fever and infection. At the age of 68, he traveled to Puri and passed away on 11 June 1904 at the Sri Jagannath Temple, fulfilling his own astrological prediction of his death.[2][6]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Palm-leaf_manuscripts_in_Odisha