Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

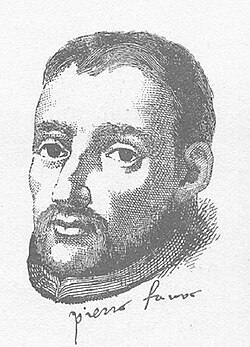

Peter Faber

View on Wikipedia

Peter Faber, SJ (French: Pierre Lefevre or Favre, Latin: Petrus Faber) (13 April 1506 – 1 August 1546)[1] was a Savoyard Catholic priest, theologian and co-founder of the Society of Jesus, along with Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier. Pope Francis announced his canonization in 2013.

Key Information

Life

[edit]Early life

[edit]Faber was born in 1506 to a peasant family in the village of Villaret, in the Duchy of Savoy (now Saint-Jean-de-Sixt in the French Department of Haute-Savoie). As a boy, he was a shepherd in the high pastures of the French Alps.[2] He had little education, but a remarkable memory; he could hear a sermon in the morning and then repeat it verbatim in the afternoon for his friends.[1] Two of his uncles were Carthusian priors.[3] At first, he was entrusted to the care of a priest at Thônes and later to a school in the neighboring village of La Roche-sur-Foron.

In 1525, Faber went to Paris to pursue his studies. He was admitted to the Collège Sainte-Barbe, the oldest school in the University of Paris, where he shared his lodgings with Francis Xavier.[1] There Faber's spiritual views began to develop, influenced by a combination of popular devotion, Christian humanism, and late medieval scholasticism.[3] Faber and Xavier became close friends and both received the degree of Master of Arts on the same day in 1530. At the university, Faber also met Ignatius of Loyola and became one of his associates. He tutored Loyola in the philosophy of Aristotle, while Loyola tutored Faber in spiritual matters.[2] Faber wrote of Loyola's counsel: "He gave me an understanding of my conscience and of the temptations and scruples I have had for so long without either understanding them or seeing the way by which I would be able to get peace."[4] Xavier, Faber, and Loyola all became roommates at the University of Paris and are all recognized by the Jesuits as founders of the Society of Jesus.

Jesuit preacher

[edit]

Faber was the first among the small circle of men who formed the Society of Jesus to be ordained. Having become a priest on 30 May 1534, he received the religious vows of Ignatius and his five companions at Montmartre on 15 August.[5]

Upon graduation, Ignatius returned to Spain for a period of convalescence, after instructing his companions to meet in Venice and charging Faber with conducting them there.[1] After Loyola himself, Faber was the one whom Xavier and his companions esteemed the most.[6] Leaving Paris on 15 November 1536, Faber and his companions rejoined Loyola at Venice in January 1537. When war between Venice and the Turks prevented them from evangelizing the Holy Land as they planned,[4] they decided to form the community that became the Society of Jesus, also known as the Jesuit Order. The group then traveled to Rome where they put themselves at the disposal of Pope Paul III. After Faber spent some months preaching and teaching, the Pope sent him to Parma and Piacenza, where he brought about a revival of Christian piety.[6]

Recalled to Rome in 1540, Faber was sent to Germany to uphold the position of the Catholic Church at the Diet of Worms and then at the Diet of Ratisbon in 1541.[4] Another Catholic theologian, Johann Cochlaeus, reported that Faber avoided theological debate and emphasized personal reformation, calling him "a master of the life of the affections".[4] Faber was startled by the unrest that the Protestant movement had stirred up in Germany and by the decadence he found in the Catholic hierarchy. He decided that the remedy did not lie in discussions with the Protestants but in the reform of the Roman Catholic, especially of the clergy. For ten months, at Speyer, at Ratisbon, and at Mainz, he conducted himself with gentleness with all those with whom he dealt. He influenced princes, prelates, and priests who opened themselves to him and amazed people by the effectiveness of his outreach.[7] Faber possessed the gift of friendship to a remarkable degree. He was famous not for his preaching, but for his engaging conversations and his guidance of souls. He crisscrossed Europe on foot, guiding bishops, priests, nobles, and common people alike in the Spiritual Exercises.[8]

As a lone Jesuit often on the move, Faber never felt alone because he walked in a world whose denizens included saints and angels. He would ask the saint of the day and all the saints "to obtain for us not only virtues and salvation for our spirits but in particular whatever can strengthen, heal, and preserve the body and each of its parts". His guardian angel, above all, became his chief ally. He sought support from the saints and angels both for his personal sanctification and in his evangelization of communities. Whenever he entered a new town or region, Faber implored the aid of the particular angels and saints associated with that place. Through the intercession of his allies, Faber could enter even a potentially hostile region assured of a spiritual army at his side. As he desired to bring each person he met to a closer relationship through spiritual friendship and conversation, he would invoke the intercession of the person's guardian angel.[9]

Called to Spain by Loyola, he visited Barcelona, Zaragoza, Medinaceli, Madrid, and Toledo.[4] In January 1542 the pope ordered him to Germany again. For the next nineteen months, Faber worked for the reform of Speyer, Mainz, and Cologne. The Archbishop of Cologne, Hermann of Wied, favored Lutheranism, which he later publicly embraced. Faber gradually gained the confidence of the clergy and recruited many young men to the Jesuits, among them Peter Canisius. After spending some months at Leuven in 1543, where he implanted the seeds of numerous vocations among the young, he returned to Cologne. Between 1544 and 1546, Faber continued his work in Portugal and Spain.[2] Through his influence while at the royal court of Lisbon, Faber was instrumental in establishing the Society of Jesus in Portugal. There and in Spain, he was a fervent and effective preacher. He was called to preach in the principal cities of Spain, where he aroused fervor among the local populations and fostered vocations to the clergy. Among them there was Francis Borgia, another significant future Jesuit. King John III of Portugal wanted Faber made Patriarch of Ethiopia.[7] Simão Rodrigues, co-founder of the Jesuit order, wrote that Faber was "endowed with charming grace in dealing with people, which up to now I must confess I have not seen in anyone else. Somehow he entered into friendship in such a way, bit by bit coming to influence others in such a manner, that his very way of living and gracious conversation powerfully drew to the love of God all those with whom he dealt."[4] He then worked in several Spanish cities, including Valladolid, Salamanca, Toledo, Galapagar, Alcalá, and Madrid.[4]

Death

[edit]In 1546, Faber was appointed by Pope Paul III to act as a peritus (expert) on behalf of the Holy See at the Council of Trent. Faber, at age 40, was exhausted by his incessant efforts and his unceasing journeys, always made on foot. In April 1546, he left Spain to attend the Council and reached Rome, weakened by fever, on 17 July 1546. He died, reportedly in the arms of Loyola, on 1 August 1546.[1][10] Faber's body was initially buried at the Church of Our Lady of the Way, which served as a center for the Jesuit community. When that church was demolished to allow for the construction of the Church of the Gesù, his remains and those of others among the first Jesuits were exhumed.[1] His remains are now in the crypt near the entrance to the Gesù.[4]

Writings

[edit]Faber kept a diary of his spiritual life known as his Memoriale. Most of it dates from June 1542 to July 1543, with some additional entries from 1545 and a final brief entry made in January 1546. It begins with a quotation from Psalms: "Bless the Lord, O my soul, and forget not all his benefits." It takes the form of a series of conversations, mostly between God and Faber with occasional contributions on the part of various saints and Faber's colleagues.[4]

Peter Faber authored "The Blessed Sacrament" which proffers a strong argument for the existence and nature of God.

Veneration

[edit]Those who had known Faber in life already invoked him as a saint. Francis de Sales, whose character recalled that of Faber's, never spoke of him except as a saint. He is remembered for his travels through Europe promoting Catholic renewal and his great skill in directing the Spiritual Exercises. Faber was beatified on 5 September 1872.[7] His feast day is celebrated on 2 August by the Society of Jesus. Faber was honored as part of the 2006 Jesuit Jubilee Year which celebrated the 500th anniversary of the birth of Francis Xavier, the 500th anniversary of the birth of Peter Faber, and the 450th anniversary of the death of Ignatius Loyola.

Pope Francis, on his own 77th birthday, 17 December 2013, announced Faber's canonization.[11] He used a process known as equipollent canonization, which dispenses with the standard judicial procedures and ceremonies in the case of someone long venerated. Faber is regarded as one of Pope Francis' favorite saints. A few weeks earlier, Francis had praised Faber's "dialogue with all, even the most remote and even with his opponents; his simple piety, a certain naïveté perhaps, his being available straightaway, his careful interior discernment, the fact that he was a man capable of great and strong decisions but also capable of being so gentle and loving".[12] Francis gave further thanks for Faber's canonization when he celebrated Mass in Rome on 3 January 2014, at the Church of the Gesù,[13] and made reference to him in a list of Jesuit priests associated with devotion to the Sacred Heart in his 2024 encyclical letter on this subject, Dilexit nos.[14]

Legacy

[edit]The Saint Peter Faber Jesuit Community at Boston College is a residence for Jesuits in formation.[15]

Creighton University confers the Blessed Peter Faber Integrity Award on a student, faculty or staff member who is involved in activities that promote integrity, social justice, peace, and religious, racial, and cultural harmony and is able to inspire and lead others to distill their values and integrity.[16]

Saint Peter Faber House at Gonzaga University is an extension of the University Ministry office reserved for preparing retreats and further developing University Ministry programs.[17]

The Faber Center for Ignatian Spirituality was adopted as a ministry of Marquette University in November 2005.[18]

The Peter Faber Chapel serves as the central space for the University of Scranton's Retreat Center at Chapman Lake, about 30 minutes north of Scranton, PA.[19]

The St. Peter Faber conference room in Loyola Hall at Manresa House of Retreats, Convent, Louisiana, is the location where men on retreat are directed through the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola[20]

The School of Business at Australian Catholic University is known as the Peter Faber School of Business.

Faber Hall at Fordham University in the Bronx, New York, is a residence hall and administrative building.[21]

It was announced in Publishers Weekly on 26 October 2016 that Loyola Press has contracted Jon M. Sweeney, the author of The Pope Who Quit and other historical books, to write a new narrative life of Saint Peter Faber.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Jesuit Saints and Martyrs, 2nd ed". LoyolaPress.com. 1998. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ a b c ""Saint Peter Faber, SJ (1506–1546)", Ignatian Spirituality". Ignatian Spirituality. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ a b "The Spirituality of Peter Faber" (PDF). 2005. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Padberg, John W. (17 July 2006). "A Saint Too Little Known". America.

- ^ Michael Servetus Research Archived 11 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Website that includes graphical documents in the University of Paris of: Ignatius of Loyola, Francis Xavier, Alfonso Salmerón, Nicholas Bobadilla, Peter Faber and Simao Rodrigues, as well as Michael de Villanueva ("Servetus")

- ^ a b Suau, Pierre (1911). "Bl. Peter Faber". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company: Newadvent.org. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ a b c "Blessed Peter Faber". sacredspace.ie. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Blessed Peter Faber". Ucanews.com. 2 August 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Gavin, John. "Invisible Allies: Peter Faber's Apostolic Devotion to the Saints" (PDF). New Jesuit Review, Vol.2, No.7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Favre, Pierre Manus online

- ^ Allen Jr., John L. (17 December 2013). "It's official: Jesuit Fr. Peter Faber is a saint". National Catholic Reporter. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Tornielli, Andrea (24 November 2013). "French Jesuit priest Peter Faber to be made a saint in December". Vatican Insider. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ "Francis remembers St. Peter Favre". Vatican Insider. 2 January 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ Pope Francis, Dilexit nos, paragraph 146, published on 24 October 2024, accessed on 14 February 2025

- ^ "Faber Jesuit Community". Faberjc.org. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ ""Blessed Peter Faber Integrity Award", Creighton University" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Faber House, Gonzaga". Gonzaga.edu. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Faber Center, Marquette University". Marquette.edu. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Honoring The Bishops Of Scranton, Church And The Jesuits: The Campus". Scranton.edu. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola

- ^ Michele, Chen. "Faber Hall". www.fordham.edu.

- ^ "Religion Book Deals: October 2016".

Sources

[edit]- William V. Bangert, To the Other Towns: A Life of Blessed Peter Favre, First Companion of St. Ignatius Loyola (Ignatius Press, 2002)

.jpg/250px-Pierre_Favre(1).jpg)

.jpg)