Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ping (networking utility)

View on Wikipedia

| Ping | |

|---|---|

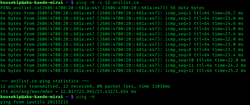

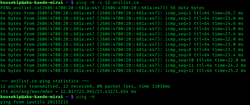

Linux version of ping | |

| Original author | Mike Muuss |

| Developers | Various open-source and commercial developers |

| Initial release | 1983 |

| Platform | Cross-platform |

| Type | Command |

| License | Public-domain, BSD, GPL, MIT |

Ping is a computer network administration software utility used to test the reachability of a host on an Internet Protocol (IP) network. It is available in a wide range of operating systems – including most embedded network administration software.

Ping measures the round-trip time for messages sent from the originating host to a destination computer that are echoed back to the source. The name comes from active sonar terminology that sends a pulse of sound and listens for the echo to detect objects under water.[1]

Ping operates by means of Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) packets. Pinging involves sending an ICMP echo request to the target host and waiting for an ICMP echo reply. The program reports errors, packet loss, and a statistical summary of the results, typically including the minimum, maximum, the mean round-trip times, and standard deviation of the mean.

Command-line options and terminal output vary by implementation. Options may include the size of the payload, count of tests, limits for the number of network hops (TTL) that probes traverse, interval between the requests and time to wait for a response. Many systems provide a companion utility ping6, for testing on Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6) networks, which implement ICMPv6.

History

[edit]

The ping utility was written by Mike Muuss in December 1983 during his employment at the Ballistic Research Laboratory, now the US Army Research Laboratory. A remark by David Mills on using ICMP echo packets for IP network diagnosis and measurements prompted Muuss to create the utility to troubleshoot network problems.[1] The author named it after the sound that sonar makes since its methodology is analogous to sonar's echolocation.[1][2] The backronym Packet Internet Groper for PING has been used for over 30 years. Muuss says that, from his point of view, PING was not intended as an acronym but he has acknowledged Mills's expansion of the name.[1][3] The first released version was public domain software; all subsequent versions have been licensed under the BSD license. Ping was first included in 4.3BSD.[4] The FreeDOS version was developed by Erick Engelke and is licensed under the GPL.[5] Tim Crawford developed the ReactOS version. It is licensed under the MIT License.[6]

Any host must process ICMP echo requests and issue echo replies in return.[7]

Invocation example

[edit]The following is the output of running ping on Linux for sending five probes (1-second interval by default, configurable via -i option) to the target host www.example.com:

$ ping -c 5 www.example.com

PING www.example.com (93.184.216.34): 56 data bytes

64 bytes from 93.184.216.34: icmp_seq=0 ttl=56 time=11.632 ms

64 bytes from 93.184.216.34: icmp_seq=1 ttl=56 time=11.726 ms

64 bytes from 93.184.216.34: icmp_seq=2 ttl=56 time=10.683 ms

64 bytes from 93.184.216.34: icmp_seq=3 ttl=56 time=9.674 ms

64 bytes from 93.184.216.34: icmp_seq=4 ttl=56 time=11.127 ms

--- www.example.com ping statistics ---

5 packets transmitted, 5 packets received, 0.0% packet loss

round-trip min/avg/max/stddev = 9.674/10.968/11.726/0.748 ms

The output lists each probe message and the results obtained. Finally, it lists the statistics of the entire test. In this example, the shortest round-trip time was 9.674 ms, the average was 10.968 ms, and the maximum value was 11.726 ms. The measurement had a standard deviation of 0.748 ms.

Error indications

[edit]In cases of no response from the target host, most implementations display either nothing or periodically print notifications about timing out. Possible ping results indicating a problem include the following:

- H, !N or !P – host, network or protocol unreachable

- S – source route failed

- F – fragmentation needed

- U or !W – destination network/host unknown

- I – source host is isolated

- A – communication with destination network administratively prohibited

- Z – communication with destination host administratively prohibited

- Q – for this ToS the destination network is unreachable

- T – for this ToS the destination host is unreachable

- X – communication administratively prohibited

- V – host precedence violation

- C – precedence cutoff in effect

In case of error, the target host or an intermediate router sends back an ICMP error message, for example host unreachable or TTL exceeded in transit. In addition, these messages include the first eight bytes of the original message (in this case, the header of the ICMP echo request, including the quench value), so the ping utility can match responses to originating queries.[8]

Message format

[edit]ICMP packet transported with IPv4

[edit]An ICMP packet transported with IPv4 looks like this.

| Offset | Octet | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octet | Bit | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

| 0 | 0 | Version (4) | IHL (5) | DSCP (0) | ECN (0) | Total length | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 32 | Identification | Flags | Fragment offset | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | 64 | Time to live | Protocol (1) | Header checksum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 96 | Source address | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | 128 | Destination address | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 160 | Type (8) | Code (0) | Checksum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 192 | Identifier | Sequence number | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 | 224 | (Payload) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32 | 256 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Type: 8 bits

- Set to 8 to indicate 'Echo Request'.[9]

- Checksum: 16 bits

- Checksum is the 16-bit ones' complement of the ones' complement sum of the ICMP packet, starting with the Type field,[10] including the Payload. The IP header is not included.

- Identifier: 16 bits

- Can be used by the client to match the reply with the request that caused the reply.

- Sequence number: 16 bits

- Can be used by the client to match the reply with the request that caused the reply.

- Payload: variable length

- Optional. Payload for the different kind of answers; can be an arbitrary length, left to implementation detail.

Most Linux systems use a unique Identifier for every ping process, and Sequence number is an increasing number within that process. Windows uses a fixed Identifier, which varies between Windows versions, and a Sequence number that is only reset at boot time.

The Echo Reply is returned as:

| 20 | 160 | Type (0) | Code (0) | Checksum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 192 | Identifier | Sequence number | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 | 224 | (Payload) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32 | 256 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Type: 8 bits

- Set to 0 to indicate 'Echo Reply'.[9]

- Identifier: 16 bits

- Copied from the Echo Request and returned.

- Sequence number: 16 bits

- Copied from the Echo Request and returned.

- Payload: variable length

- Optional. Payload is copied from the Echo Request and returned.

ICMPv6 packet transported with IPv6

[edit]An ICMP packet transported with IPv6 looks like this.

| Offset | Octet | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octet | Bit | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

| 0 | 0 | Version (6) | Traffic class | Flow label | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 32 | Payload length | Next header (58) | Hop limit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | 64 | Source address | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 96 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | 128 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 160 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | 192 | Destination address | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 | 224 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32 | 256 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36 | 288 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | 320 | Type (128) | Code (0) | Checksum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44 | 352 | Identifier | Sequence number | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 48 | 384 | (Payload) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 52 | 416 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Type: 8 bits

- Set to 128 to indicate 'Echo Request'.

- Identifier: 16 bits

- Can be used by the client to match the reply with the request that caused the reply.

- Sequence number: 16 bits

- Can be used by the client to match the reply with the request that caused the reply.

- Checksum: 16 bits

- The checksum is calculated from the ICMP message (starting with the Type field), prepended with an IPv6 pseudo-header.[11]

- Payload: variable length

- Optional. Payload for the different kind of answers; can be an arbitrary length, left to implementation detail.

Most Linux systems use a unique Identifier for every ping process, and Sequence number is an increasing number within that process. Windows uses a fixed Identifier, which varies between Windows versions, and a Sequence number that is only reset at boot time.

The Echo Reply is returned as:

| 40 | 320 | Type (129) | Code (0) | Checksum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44 | 352 | Identifier | Sequence number | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 48 | 384 | (Payload) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 52 | 416 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Type: 8 bits

- Set to 129 to indicate 'Echo Reply'.

- Identifier: 16 bits

- Copied from the Echo Request and returned.

- Sequence number: 16 bits

- Copied from the Echo Request and returned.

- Payload: variable length

- Optional. Payload is copied from the Echo Request and returned.

Payload

[edit]The payload of the packet is generally filled with ASCII characters, as the output of the tcpdump utility shows in the last 32 bytes of the following example (after the eight-byte ICMP header starting with 0x0800):

16:24:47.966461 IP (tos 0x0, ttl 128, id 15103, offset 0, flags [none],

proto: ICMP (1), length: 60) 192.168.146.22 > 192.168.144.5: ICMP echo request,

id 1, seq 38, length 40

0x0000: 4500 003c 3aff 0000 8001 5c55 c0a8 9216 E..<:.....\U....

0x0010: c0a8 9005 0800 4d35 0001 0026 6162 6364 ......M5...&abcd

0x0020: 6566 6768 696a 6b6c 6d6e 6f70 7172 7374 efghijklmnopqrst

0x0030: 7576 7761 6263 6465 6667 6869 uvwabcdefghi

The payload may include a timestamp indicating the time of transmission and a sequence number, which are not found in this example. This allows ping to compute the round-trip time in a stateless manner without needing to record the time of transmission of each packet.

The payload may also include a magic packet for the Wake-on-LAN protocol, but the minimum payload, in that case, is longer than shown. The Echo Request typically does not receive any reply if the host was sleeping in hibernation state, but the host still wakes up from sleep state if its interface is configured to accept wakeup requests. If the host is already active and configured to allow replies to incoming ICMP Echo Request packets, the returned reply should include the same payload. This may be used to detect that the remote host was effectively woken up by repeating a new request after some delay to allow the host to resume its network services. If the host was just sleeping in low-power active state, a single request wakes up that host just enough to allow its Echo Reply service to reply instantly if that service was enabled. The host does not need to wake up all devices completely and may return to low-power mode after a short delay. Such configuration may be used to avoid a host to enter in hibernation state, with much longer wake-up delay, after some time passed in low power active mode.[citation needed]

A packet including IP and ICMP headers must not be greater than the maximum transmission unit of the network, or risk being fragmented.

Security loopholes

[edit]To conduct a denial-of-service attack, an attacker may send ping requests as fast as possible, possibly overwhelming the victim with ICMP echo requests. This technique is called a ping flood.[12]

Ping requests to multiple addresses, ping sweeps, may be used to obtain a list of all hosts on a network.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Mike Muuss. "The Story of the PING Program". U.S. Army Research Laboratory. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

My original impetus for writing PING for 4.2a BSD UNIX came from an offhand remark in July 1983 by Dr. Dave Mills ... I named it after the sound that a sonar makes, inspired by the whole principle of echo-location ... From my point of view PING is not an acronym standing for Packet InterNet Grouper, it's a sonar analogy. However, I've heard second-hand that Dave Mills offered this expansion of the name, so perhaps we're both right.

- ^ Salus, Peter (1994). A Quarter Century of UNIX. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-54777-1.

- ^ Mills, D.L. (December 1983). Internet Delay Experiments. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC0889. RFC 889. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "man page ping section 8". www.manpagez.com.

- ^ "ibiblio.org FreeDOS Package -- ping (Networking)". www.ibiblio.org.

- ^ "GitHub - reactos/reactos: A free Windows-compatible Operating System". 8 August 2019 – via GitHub.

- ^ R. Braden, ed. (October 1989). Requirements for Internet Hosts -- Communication Layers. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC1122. STD 3. RFC 1122. Internet Standard 3. Updated by RFC 1349, 4379, 5884, 6093, 6298, 6633, 6864, 8029 and 9293.

Every host MUST implement an ICMP Echo server function that receives Echo Requests and sends corresponding Echo Replies.

- ^ "ICMP: Internet Control Message Protocol". repo.hackerzvoice.net. 13 January 2000. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ a b J. Postel (September 1981). INTERNET CONTROL MESSAGE PROTOCOL - DARPA INTERNET PROGRAM PROTOCOL SPECIFICATION. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC0792. STD 5. RFC 792. Internet Standard 5. Updates RFC 760, 777, IENs 109, 128. Updated by RFC 950, 4884, 6633 and 6918.

- ^ "RFC Sourcebook's page on ICMP". Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ A. Conta; S. Deering (March 2006). M. Gupta (ed.). Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMPv6) for the Internet Protocol Version 6 (IPv6) Specification. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC4443. STD 89. RFC 4443. Internet Standard 89. Obsoletes RFC 2463. Updates RFC 2780. Updated by RFC 4884.

- ^ "What is a Ping Flood | ICMP Flood | DDoS Attack Glossary | Imperva". Learning Center. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Dyson, Peter (1995). Mastering OS/2 Warp. Sybex. ISBN 978-0782116632.

- John Paul Mueller (2007). Windows Administration at the Command Line for Windows Vista, Windows 2003, Windows XP, and Windows 2000. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470165799.

- McElhearn, Kirk (2006). The Mac OS X Command Line: Unix Under the Hood. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470113851.

External links

[edit]- – Solaris 11.4 Reference Manual

- – FreeBSD System Manager's Manual

- – Linux Programmer's Manual – Administration and Privileged Commands from Manned.org

- ping at Microsoft Docs

Ping (networking utility)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

Ping is a fundamental networking diagnostic utility that operates by sending Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) Echo Request packets to a specified target host and measuring the round-trip time (RTT) based on the receipt of corresponding Echo Reply packets.[8][9] This process allows network administrators and users to assess basic IP-level connectivity without requiring specialized software on the target device beyond standard ICMP support.[10] The primary purposes of ping include verifying whether a remote host is reachable over an IP network, estimating network latency through RTT calculations, and detecting potential packet loss by observing the percentage of replies received from a series of probes.[11][12] These functions make ping an indispensable tool for troubleshooting connectivity issues in TCP/IP-based environments, from local area networks to the global internet.[13] Originating in the early days of modern networking, ping was developed in December 1983 by Mike Muuss at the U.S. Army Ballistic Research Laboratory as a quick response to IP network problems; its name derives from the sonar "ping" technique, reflecting the echo-location principle of sending a signal and awaiting its return.[14] As a simple yet essential component of TCP/IP protocol stacks, ping has become a standard utility across diverse platforms, including Unix-like operating systems, Microsoft Windows, and embedded devices.[15][9] One of ping's key benefits is its non-intrusive nature, as it does not rely on target-side application services or open ports beyond basic ICMP processing, thereby minimizing interference with ongoing network operations.[16] This cross-platform ubiquity and low overhead have cemented its role as a first-line diagnostic tool in both enterprise and consumer networking contexts.[12]Basic Operation

The ping utility begins its operation when a user specifies a target IP address or hostname via the command line. The utility resolves the hostname to an IP address if necessary, constructs an ICMP Echo Request packet, and transmits it to the target device across the IP network.[10][9] Upon receipt, if the target device is operational and configured to respond, it generates and sends an ICMP Echo Reply back to the originating host. The ping utility records the round-trip time (RTT), which is the duration from sending the request to receiving the reply. This process repeats for multiple packets to assess network reliability.[8][1] After completing the series of transmissions, the utility computes aggregate statistics, including the minimum, average, and maximum RTT values, along with the percentage of packet loss based on unanswered requests. These metrics provide an overview of network latency and reachability.[9][17] Ping functions at the network layer through the Internet Protocol (IP) and Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP), independent of higher-layer transport protocols such as TCP or UDP, allowing direct testing of IP connectivity.[11][1] In typical implementations, ping sends Echo Request packets containing 56 bytes of data payload—yielding a total ICMP message size of 64 bytes including the 8-byte header—at intervals of one second, continuing until manually interrupted or after a default count of 4 to 5 packets in some systems.[18][9] The output displays successful replies with RTT values in milliseconds, such as "64 bytes from target: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=1.2 ms," while failures manifest as timeouts (e.g., "Request timed out") or indications of unreachable hosts, signaling potential connectivity issues.[10][19]History and Development

Origins in Early Networking

The ping utility was invented by Mike Muuss in December 1983 at the U.S. Army Ballistic Research Laboratory (BRL) in Aberdeen, Maryland, as a rapid diagnostic tool to troubleshoot anomalous behavior in the laboratory's IP network.[14] At the time, network diagnostics often relied on time-consuming methods, such as sending TCP packets to measure round-trip latency, which Muuss sought to replace with a simpler, faster alternative using Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) echo requests and replies.[20] This need arose during the early expansion of packet-switched networks like ARPANET, where quick connectivity verification was essential amid emerging issues in distributed systems. Muuss drew inspiration for the tool's name from the acoustic "ping" used in submarine sonar for echo-location, reflecting the program's mechanism of sending a signal and awaiting a response to confirm reachability.[14] The concept stemmed from an earlier conversation at a DARPA meeting in Norway in July 1983, where network researcher Dave Mills discussed challenges in latency testing over ARPANET; Muuss recalled this while coding ping in just a few hours to address BRL's immediate problems.[21] Rather than an acronym, "ping" evoked the sonar analogy to emphasize its straightforward echo-based operation, distinguishing it from more complex protocol tests.[20] The initial implementation consisted of approximately 1000 lines of C code for the 4.2BSD Unix operating system, leveraging raw sockets to craft and send ICMP packets directly.[22][21] Muuss released ping as public domain software almost immediately after its creation, sharing the source code with colleagues via email and early network distributions, which facilitated its rapid dissemination within the Unix community.[14] Ping saw early adoption in military networks such as MILNET, which had been separated from ARPANET earlier in 1983 to handle unclassified defense traffic, and in the burgeoning Internet for basic reachability checks as interconnected systems grew more complex during the mid-1980s.[23] This utility provided a lightweight means to verify host availability without establishing full connections, proving invaluable in environments transitioning from experimental ARPANET topologies to wider TCP/IP deployments.[24]Standardization and Evolution

The foundational standardization of the mechanisms underlying the ping utility occurred with the publication of RFC 792 in September 1981, which defined the Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) and introduced the Echo Request (Type 8) and Echo Reply (Type 0) message types for testing network reachability.[8] These protocol elements provided the essential framework for diagnostic tools like ping, predating the utility's implementation by Mike Muuss in December 1983. The ping command was written for 4.2BSD and first distributed as part of official Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) Unix releases starting with 4.3BSD and continuing in subsequent versions, establishing it as a standard network diagnostic tool in Unix-like environments.[14][25] Ping's evolution expanded its availability across operating systems and protocols. In the 1990s, it was ported to Microsoft Windows as part of the TCP/IP protocol implementation in Windows NT 3.1 (released in 1993), where it became accessible via the command prompt for connectivity testing.[9] Linux distributions adopted and enhanced ping, with libraries like liboping introduced in the mid-2000s to enable efficient parallel pinging of multiple hosts over IPv4 or IPv6.[26] IPv6 integration was formalized in RFC 4443 (March 2006), which specified ICMPv6 Echo Request (Type 128) and Echo Reply (Type 129) messages, allowing ping to operate seamlessly in IPv6 environments while maintaining backward compatibility with IPv4.[4] Significant milestones include the early inclusion of options such as flood mode in Unix ping implementations, designed for high-rate packet transmission to assess network capacity under load, as noted in the original tool's documentation from 1983 onward.[14] Post-2000s developments saw increased scrutiny of ping's security implications, leading to the deprecation or restriction of ICMP Echo responses in many modern firewalls to mitigate risks like reconnaissance and denial-of-service attacks, such as the ping flood.[27] As of 2025, ping remains a core, unchanged component of major operating systems including Linux, Windows, macOS, and BSD variants, serving as an essential diagnostic tool for IP network troubleshooting. Complementary extensions, such as the fping utility, have proliferated for multi-host testing scenarios, but the protocol's core—rooted in ICMP standards—has seen no major alterations since IPv6 adoption.[28]Usage and Invocation

Command Syntax and Options

The ping command follows a general syntax ofping [options] <host>, where <host> specifies the target as either an IP address or a hostname, and options modify the behavior of the transmission.[29][9] This structure leverages the ICMP Echo Request mechanism to test network reachability, with variations across platforms in option naming and availability.[30] On Unix-like systems such as Linux and BSD, the default sends continuous packets until interrupted, while Windows defaults to four packets unless specified otherwise.[29][9]

Core options enable customization of transmission parameters. The packet count is controlled by -c count on Unix-like systems to limit the number of Echo Requests sent, or -n count on Windows for the same purpose.[29][9] The interval between packets is set via -i interval (in seconds) on Unix-like platforms, though Windows lacks a direct equivalent and uses a fixed one-second interval.[30] Payload size is adjusted with -s packetsize on Linux and BSD or -l size on Windows, typically ranging from 0 to 65,500 bytes depending on the system.[29][9] Timeout per response is specified by -W waittime (in seconds) on Unix-like systems or -w timeout (in milliseconds) on Windows, after which a packet is considered lost.[30][9] Verbose mode, invoked with -v on Unix-like platforms, displays additional details such as IP headers, whereas Windows provides basic output without a dedicated verbose flag.[29]

Platform-specific nuances reflect differences in implementation and security policies. Linux and BSD derivatives, including macOS, support -a for audible alerts upon receiving responses, useful for monitoring without visual attention.[29][30] Flood mode, enabled by -f on these systems (requiring superuser privileges), sends packets as fast as possible to stress-test networks, but Windows omits this option by default for security reasons, relying instead on continuous pinging with -t.[29][9] macOS, based on BSD, supports sweep pings for incremental payload testing using -G sweepmaxsize, -g sweepminsize, and -h sweepincrsize, in addition to standard options like -i and -s.[31]

Non-standard extensions provide further control in multi-interface or diagnostic scenarios. The -n flag on Unix-like systems suppresses DNS lookups, outputting only numeric IP addresses to avoid resolution delays.[29] Interface binding is achieved with -I interface or -I source_ip on Linux and BSD for selecting the outgoing network interface on multi-homed hosts, while Windows uses /S srcaddr to specify the source IP address for IPv6 pings.[30][9] These options, while not universally standardized, enhance precision in complex network environments.[29]

Practical Examples

One of the most straightforward applications of the ping utility is performing a simple reachability test to verify if a remote host is accessible over the network. For instance, executingping google.com on a Unix-like system sends ICMP echo request packets continuously until interrupted; the example below assumes a count limit for illustration and reports the round-trip time (RTT) for each reply received. A typical successful output from this command appears as follows:

PING google.com (142.250.191.78) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 142.250.191.78: icmp_seq=1 ttl=118 time=14.2 ms

64 bytes from 142.250.191.78: icmp_seq=2 ttl=118 time=13.9 ms

64 bytes from 142.250.191.78: icmp_seq=3 ttl=118 time=15.1 ms

64 bytes from 142.250.191.78: icmp_seq=4 ttl=118 time=14.5 ms

--- google.com ping statistics ---

4 packets transmitted, 4 received, 0% packet loss, time 3004ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 13.9/14.4/15.1/0.5 ms

PING google.com (142.250.191.78) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 142.250.191.78: icmp_seq=1 ttl=118 time=14.2 ms

64 bytes from 142.250.191.78: icmp_seq=2 ttl=118 time=13.9 ms

64 bytes from 142.250.191.78: icmp_seq=3 ttl=118 time=15.1 ms

64 bytes from 142.250.191.78: icmp_seq=4 ttl=118 time=14.5 ms

--- google.com ping statistics ---

4 packets transmitted, 4 received, 0% packet loss, time 3004ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 13.9/14.4/15.1/0.5 ms

ping -c 10 -i 0.5 8.8.8.8, which targets Google's public DNS server and sends 10 packets at 0.5-second intervals. This allows for a better assessment of average response times under controlled conditions. A sample output might show:

PING 8.8.8.8 (8.8.8.8) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=1 ttl=117 time=12.4 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=2 ttl=117 time=11.7 ms

... (additional lines for seq=3 to 10)

--- 8.8.8.8 ping statistics ---

10 packets transmitted, 10 received, 0% packet loss, time 4500ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 11.2/12.8/14.3/1.0 ms

PING 8.8.8.8 (8.8.8.8) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=1 ttl=117 time=12.4 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=2 ttl=117 time=11.7 ms

... (additional lines for seq=3 to 10)

--- 8.8.8.8 ping statistics ---

10 packets transmitted, 10 received, 0% packet loss, time 4500ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 11.2/12.8/14.3/1.0 ms

ping -c 3 [localhost](/page/Localhost) tests the loopback interface, typically yielding near-instantaneous replies:

PING [localhost](/page/Localhost) (127.0.0.1) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 127.0.0.1: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=0.045 ms

64 bytes from 127.0.0.1: icmp_seq=2 ttl=64 time=0.032 ms

64 bytes from 127.0.0.1: icmp_seq=3 ttl=64 time=0.038 ms

--- [localhost](/page/Localhost) ping statistics ---

3 packets transmitted, 3 received, 0% [packet loss](/page/Packet_loss), time 2002ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 0.032/0.038/0.045/0.006 ms

PING [localhost](/page/Localhost) (127.0.0.1) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 127.0.0.1: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=0.045 ms

64 bytes from 127.0.0.1: icmp_seq=2 ttl=64 time=0.032 ms

64 bytes from 127.0.0.1: icmp_seq=3 ttl=64 time=0.038 ms

--- [localhost](/page/Localhost) ping statistics ---

3 packets transmitted, 3 received, 0% [packet loss](/page/Packet_loss), time 2002ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 0.032/0.038/0.045/0.006 ms

ping -c 3 example.remotehost.com on an unreachable remote host might produce timeouts, such as:

PING example.remotehost.com (unresolved) 56(84) bytes of data.

--- example.remotehost.com ping statistics ---

3 packets transmitted, 0 received, 100% [packet loss](/page/Packet_loss), time 2002ms

PING example.remotehost.com (unresolved) 56(84) bytes of data.

--- example.remotehost.com ping statistics ---

3 packets transmitted, 0 received, 100% [packet loss](/page/Packet_loss), time 2002ms

ping -f target (requiring superuser privileges on Unix-like systems) sends packets as quickly as possible, often visualized with dots for each sent packet and exclamation marks for each received response. A brief execution against a responsive target like 8.8.8.8 might output a stream like .........!!!!!!!! where dots represent sent packets and exclamation marks represent received responses, followed by statistics upon interruption (e.g., Ctrl+C). This mode is useful for stress-testing network capacity but must be used cautiously, as it generates high traffic volumes that could overwhelm links or be misinterpreted as a denial-of-service attempt; it is generally restricted to controlled environments on owned infrastructure.[33]

Protocol Mechanics

ICMP Echo Request and Reply

The ping utility employs the Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) to perform its core function of verifying host reachability through echo requests and replies. In the IPv4 version of ICMP, as specified in RFC 792, an echo request message uses type 8 and code 0, while the corresponding echo reply uses type 0 and code 0. These messages are encapsulated in IP datagrams with the protocol number set to 1, indicating ICMP as the upper-layer protocol. The sender generates an echo request containing a variable-length data payload, along with mandatory fields including the type, code, a 16-bit checksum, a 16-bit identifier, and a 16-bit sequence number. The checksum is computed as the one's complement sum of the entire ICMP message (with the checksum field temporarily zeroed), ensuring integrity during transmission. Upon receiving an echo request, the destination host processes it by generating an echo reply that copies the original payload entirely and unmodified, preserves the identifier and sequence number, reverses the source and destination IP addresses, changes the message type to 0, and recalculates the checksum. The identifier serves to distinguish multiple concurrent ping instances or processes on the sender, while the sequence number enables correlation of individual requests and replies, particularly during tests involving multiple packets sent in succession. Both fields may be set to zero if not needed for matching, but their inclusion facilitates reliable diagnostics in complex network scenarios. This echo mechanism is inherently connectionless, operating directly at the network layer without the use of transport-layer port numbers, which aligns with ICMP's role in providing diagnostic feedback rather than establishing sessions. For IPv6 networks, ICMPv6 employs an analogous process with echo request type 128 and echo reply type 129 (both with code 0), retaining the same identifier, sequence number, and payload-echoing behavior, though encapsulated using IPv6's next header value of 58.[4]IPv4 and IPv6 Differences

The ping utility operates differently over IPv4 and IPv6 due to the distinct protocol architectures of each Internet Protocol version. For IPv4, ping relies on the Internet Control Message Protocol version 4 (ICMPv4), which is defined in RFC 792 and serves as an error-reporting and diagnostic mechanism integral to IPv4 networks.[8] ICMPv4 Echo Request and Reply messages are encapsulated within an IPv4 header, typically 20 bytes in length without options, followed by an 8-byte ICMPv4 header containing fields for type, code, checksum, identifier, and sequence number.[8] In some Unix-like systems, such as BSD derivatives including FreeBSD and macOS, the standardping command is primarily for IPv4 operations, with a separate ping6 utility for IPv6 to avoid ambiguity in dual-stack environments; in contrast, Linux implementations often support both protocols in the unified ping command using flags like -4 or -6.

In contrast, IPv6 ping employs the Internet Control Message Protocol version 6 (ICMPv6), outlined in RFC 4443, which is more tightly integrated with the IPv6 protocol suite as part of the IPng (IPv6) specifications.[4] ICMPv6 Echo Request messages use type 128, while Echo Replies use type 129, and these are carried in IPv6 packets with a fixed 40-byte base header, potentially extended by optional headers for routing, fragmentation, or other functions.[4] Unlike ICMPv4, ICMPv6 requires a fully operational IPv6 stack on the host, as it cannot fallback to IPv4 mechanisms, and it supports additional roles beyond basic diagnostics, such as address resolution.[4]

Key operational differences arise from IPv6's design philosophy, which eliminates broadcast addressing in favor of multicast for efficiency and scalability. IPv6 mandates router advertisements via ICMPv6 messages to facilitate host discovery and configuration, as specified in the Neighbor Discovery Protocol (NDP) in RFC 4861. Consequently, ping over IPv6 may invoke NDP processes, such as Neighbor Solicitation (type 135), which use solicited-node multicast addresses (e.g., ff02::1:ff00:0/104) to resolve link-layer addresses without flooding the network like IPv4's ARP broadcasts. This multicast-based approach reduces overhead in dense networks and supports features like duplicate address detection, though it can introduce slight latency in initial pings due to resolution steps.[35] Multicast is also leveraged for broader tests, such as pinging all-nodes (ff02::1) or all-routers (ff02::2) groups, enabling network-wide diagnostics unavailable in IPv4 without additional tools.

Compatibility between the two is achieved in dual-stack systems, where hosts maintain both IPv4 and IPv6 connectivity. The ping command in modern implementations supports explicit selection via the -6 flag to force IPv6 usage, ensuring unambiguous targeting of IPv6 addresses even when hostname resolution yields both address families. This evolution reflects broader adoption trends: following IPv4 address exhaustion pressures in the late 2000s, operating systems transitioned to include IPv6 support by default around 2010, enabling it by default in major platforms like Windows, Linux distributions, and macOS thereafter.[36]

Data and Message Format

Packet Structure for IPv4

The ping utility over IPv4 encapsulates ICMP Echo Request (type 8) or Echo Reply (type 0) messages within an IPv4 datagram, resulting in a packet structure comprising a fixed 20-byte IPv4 header and an 8-byte ICMPv4 header, with optional data payload following.[8][37] The IPv4 header specifies version 4 (4 bits) and an Internet Header Length (IHL) of 5 (4 bits, indicating 20 bytes without options), followed by an 8-bit Type of Service field (typically 0 for ping), a 16-bit Total Length field (minimum 28 bytes for an empty payload), a 16-bit Identification field (used for fragmentation matching), 3-bit Flags (where the Don't Fragment bit is often set to 1 to prevent intermediate routers from fragmenting the packet and to aid in path MTU discovery), a 13-bit Fragment Offset (0 for unfragmented ping packets), an 8-bit Time to Live (TTL, commonly 64 or 255), an 8-bit Protocol field set to 1 (indicating ICMP), a 16-bit Header Checksum (computed over the IPv4 header), a 32-bit Source Address, and a 32-bit Destination Address.[37][38] The ICMPv4 header, which begins immediately after the IPv4 header, consists of an 8-bit Type field (8 for Echo Request, 0 for Echo Reply), an 8-bit Code field (0 for both), a 16-bit Checksum (covering the entire ICMP message including payload), a 16-bit Identifier (used to match requests with replies, often set to the process ID of the ping invocation), and a 16-bit Sequence Number (incremented for each successive packet to track order).[8] The Checksum is calculated as the one's complement of the one's complement sum of all 16-bit words in the ICMP header and payload; during computation, the checksum field is zeroed, and if the message length is odd, a single zero byte is logically padded at the end for summing (though not transmitted).[8] For a minimal ping packet with no data payload, the Total Length in the IPv4 header is 28 bytes (20-byte IPv4 header + 8-byte ICMPv4 header), ensuring compatibility with standard MTU sizes while allowing customization via ping options for larger payloads.[8][37] In practice, the Don't Fragment (DF) bit in the IPv4 Flags is set by many ping implementations to avoid fragmentation issues along the path, triggering ICMP "Fragmentation Needed" messages if the packet exceeds the path MTU, which facilitates diagnostic troubleshooting.[38]| Field | Size (bits) | Description (IPv4 Header) |

|---|---|---|

| Version | 4 | Set to 4. |

| IHL | 4 | 5 (20 bytes). |

| Type of Service | 8 | Typically 0. |

| Total Length | 16 | Minimum 28 bytes. |

| Identification | 16 | For fragmentation (0 if unfragmented). |

| Flags | 3 | Don't Fragment (DF) flag often set to 1. |

| Fragment Offset | 13 | 0 for ping. |

| TTL | 8 | Hop limit (e.g., 64). |

| Protocol | 8 | 1 (ICMP). |

| Header Checksum | 16 | IPv4 header integrity. |

| Source Address | 32 | Sender IPv4 address. |

| Destination Address | 32 | Target IPv4 address. |

| Field | Size (bits) | Description (ICMPv4 Header) |

|---|---|---|

| Type | 8 | 8 (Request) or 0 (Reply). |

| Code | 8 | 0. |

| Checksum | 16 | ICMP message integrity (one's complement sum). |

| Identifier | 16 | Matches request/reply. |

| Sequence Number | 16 | Packet ordering. |

Packet Structure for IPv6

The IPv6 packet used for ping consists of a fixed 40-byte IPv6 header followed by an 8-byte ICMPv6 header and optional data payload, resulting in a minimum total size of 48 bytes for an Echo Request or Reply with no data.[39][4] The IPv6 header begins with a 4-bit Version field set to 6, followed by an 8-bit Traffic Class field for priority and congestion notification, and a 20-bit Flow Label for packet handling in flows. This is succeeded by a 16-bit Payload Length indicating the size of the ICMPv6 message and any data, an 8-bit Next Header field set to 58 to denote ICMPv6, and an 8-bit Hop Limit analogous to the IPv4 TTL. The header concludes with 128-bit Source Address and Destination Address fields.[39] The ICMPv6 header for Echo Request (Type 128) or Echo Reply (Type 129) starts with an 8-bit Type field, an 8-bit Code field set to 0, and a 16-bit Checksum covering the entire ICMPv6 message including the payload. This is followed by a 16-bit Identifier and a 16-bit Sequence Number, which mirror the structure used in IPv4 ICMP for matching requests to replies. The optional data payload, if present, follows immediately and is typically echoed unchanged in replies.[4] The ICMPv6 Checksum is computed as the 16-bit one's complement sum of the ICMPv6 message prepended with an IPv6 upper-layer pseudo-header, which includes the 128-bit source and destination addresses, the 32-bit upper-layer packet length, a 24-bit zero field, and an 8-bit Next Header field set to 58. This integration ensures integrity checks incorporate IPv6 addressing details, differing from IPv4 by using the full 128-bit addresses and fixed header elements.[4][39] While IPv6 supports extension headers such as Hop-by-Hop Options or Destination Options inserted between the base header and ICMPv6 payload, standard ping implementations typically omit these to maintain simplicity and minimize overhead, using only the base IPv6 and ICMPv6 headers.[39]Echo Payload and Customization

The echo payload forms the variable-length data portion of ICMP Echo Request and Reply messages, following the fixed 8-byte header that includes fields for type, code, checksum, identifier, and sequence number. As defined in RFC 792 for IPv4 and RFC 4443 for IPv6, this payload contains arbitrary data supplied by the sender, which the recipient must return unchanged in the reply to confirm both reachability and data integrity.[8][4] In standard implementations, the default payload size is 56 bytes on Unix-like systems (including Linux and BSD variants) for both IPv4 and IPv6, resulting in a total ICMP message of 64 bytes; this data is typically filled with null bytes (0x00) or an incrementing pattern, such as sequential byte values from 0x00 to 0xFF, to aid in basic integrity verification. On Windows systems, the default is 32 bytes of null bytes, yielding a 40-byte ICMP message.[9][34] Users can customize the payload through command-line options in ping utilities, such as the -s flag on Linux and Unix systems to specify the number of payload bytes (e.g., 1472 bytes for IPv4 or 1452 bytes for IPv6 to test Ethernet path MTU, accounting for the respective IP and ICMP headers totaling 1500 bytes). Advanced tools support additional patterns, including embedded timestamps for latency measurement or random data for stress testing network handling of variable content.[40][38] The payload serves key diagnostic purposes beyond basic connectivity: it facilitates path MTU discovery by incrementally increasing size while setting the IP Don't Fragment bit, prompting intermediate routers to return ICMP "Fragmentation Needed" messages (type 3, code 4 in IPv4 per RFC 792; type 2 in IPv6 per RFC 4443) indicating the maximum transmittable unit. Additionally, comparing sent and echoed payloads detects bit errors or alterations in transit.[8][4] Payloads exceeding 65,535 bytes are invalid, as the total IP datagram length field is limited to 16 bits (maximum 65,535 bytes including headers), constraining practical payloads to about 65,507 bytes in IPv4 (subtracting 20-byte header and 8-byte ICMP header) or 65,487 bytes in IPv6 (subtracting 40-byte header and 8-byte ICMPv6 header, without extension headers). Many firewalls and security devices block oversized payloads—often above 1500 bytes—to prevent abuse in denial-of-service attacks, though this can interfere with legitimate MTU testing.[37][41]Error Handling

Common Error Types

When the ping utility sends an ICMP Echo Request and receives an error response instead of an Echo Reply, it indicates a failure in packet delivery or processing. The most common errors are ICMP error messages generated by intermediate routers or the destination host, as defined in the Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) specification.[8] ICMP Type 3, Destination Unreachable, signals that the destination cannot be reached for various reasons. This message includes a code field specifying the exact condition: code 0 (Net Unreachable) indicates the destination network is unreachable, often due to routing issues; code 1 (Host Unreachable) means the destination host is not responding on an otherwise reachable network; code 3 (Port Unreachable) is uncommon for ping since it does not target specific ports, but may occur if the ICMP protocol is misinterpreted; and code 4 (Fragmentation Needed and Don't Fragment was Set) arises when the packet exceeds the path's maximum transmission unit (MTU) and fragmentation is prohibited. Additionally, codes 9 (Destination Network Administratively Prohibited) and 10 (Destination Host Administratively Prohibited) denote firewall or policy-based blocks preventing delivery. These codes are standardized in the ICMP parameters registry.[8][42] ICMP Type 11, Time Exceeded, occurs when a packet's time-to-live (TTL) field reaches zero during transit, preventing infinite loops. Code 0 (TTL Exceeded in Transit) is the primary variant encountered by ping, where a router discards the packet and returns this error; this is frequently observed in traceroute operations but can indicate routing loops or excessive hops in standard ping usage. Code 1 (Fragment Reassembly Time Exceeded) is less relevant for unfragmented ping packets.[8][42] ICMP Type 5, Redirect, informs the sender of a better route to the destination, sent by a router when it detects suboptimal routing. Relevant codes include 1 (Redirect for Host), suggesting an alternative gateway for the specific host, and 3 (Redirect for Type of Service and Host), which accounts for service-specific routing; code 0 (Redirect for Network) and 2 (Redirect for Type of Service and Network) apply at the network level. The operating system may process these messages to update local routing tables if configured to do so (e.g., via kernel parameters), but ping itself does not handle them, continuing to send Echo Requests independently of any routing changes.[8][42][43] Beyond ICMP errors, ping may encounter non-response conditions, such as timeouts where no reply arrives within the expected interval, resulting in 100% packet loss reported in output; this often stems from packet loss, firewalls silently dropping Echo Requests, or network congestion without generating an error message.[8]Diagnostic Interpretation

The output of the ping utility typically concludes with a statistics summary that reports the number of packets sent, the number received, and the percentage lost, alongside round-trip time (RTT) metrics including the minimum, average, maximum, and standard deviation values in milliseconds.[44] These RTT statistics provide insight into network latency, where low minimum and average values (e.g., under 50 ms for local networks) suggest efficient connectivity, while high variability indicated by a large standard deviation may signal jitter from unstable links.[45] Packet loss percentages in this summary are calculated as the proportion of unreplied echo requests; losses exceeding 10% generally point to congestion, overloaded routers, or path disruptions, warranting further investigation to prevent impacts on real-time applications like VoIP.[46] In troubleshooting, intermittent packet loss in ping results often implies transient issues such as bandwidth contention during peak hours or electromagnetic interference in wireless environments, whereas consistent timeouts across multiple runs typically indicate persistent routing failures, firewall restrictions, or unreachable destinations.[47] To address potential fragmentation-related problems, administrators can combine ping diagnostics with MTU (Maximum Transmission Unit) tests by incrementally increasing packet sizes (e.g., using the -s or -l option) to identify the threshold where losses spike, helping pinpoint mismatched MTU settings between endpoints.[1] Common error messages, such as those detailed in error type classifications, should be cross-referenced with these statistics for contextual analysis. For deeper diagnostics, ping is frequently integrated with traceroute to perform hop-by-hop analysis, revealing at which intermediate router latency spikes or losses begin, thus isolating the problematic segment.[44] Long-term log analysis of ping outputs over extended periods can uncover recurring patterns, such as diurnal variations in RTT due to traffic loads, aiding proactive network management.[45] Best practices for effective ping-based troubleshooting include conducting multiple trials (e.g., sending 100 or more packets) to mitigate anomalies from single-run variability, experimenting with different payload sizes to simulate various traffic types, and initiating tests from diverse source locations or devices to differentiate local infrastructure faults from remote path issues.[1] These approaches ensure reliable interpretation, emphasizing quantitative trends over isolated results to guide targeted resolutions.[47]Security Considerations

Historical Vulnerabilities

One of the earliest vulnerabilities associated with the ping utility emerged in the 1990s through high-rate ICMP echo requests, known as ping floods, which served as a precursor to modern distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks.[48] Attackers exploited options like the flood mode (e.g., the -f flag in Unix-like systems) to send packets at maximum speed, overwhelming target systems with excessive traffic and consuming bandwidth or processing resources.[49] This simple technique, requiring minimal resources, highlighted the lack of inherent rate limiting in early network stacks and routers, allowing even modest connections to disrupt services.[50] A particularly amplified variant of the ping flood was the smurf attack, prevalent in the late 1990s, which leveraged IP directed broadcasts to magnify impact.[51] In this exploit, an attacker spoofed the source IP address of ICMP echo requests to a network's broadcast address, prompting all hosts on that subnet to reply to the victim, creating a traffic multiplication factor of up to hundreds or thousands.[52] This amplification turned a single ping into a flood from multiple responders, exacerbating denial-of-service effects on bandwidth-constrained early Internet links.[53] The vulnerability stemmed from default router configurations that forwarded directed broadcasts, a feature deprecated by RFC 2644 in 1999, which recommended disabling it to prevent such abuses.[54] CERT issued an advisory in 1998 documenting widespread smurf incidents, noting that external attackers could target internal networks by exploiting permissive broadcast handling. ICMP blind spoofing further compounded ping-related risks by enabling attackers to impersonate sources without needing visibility into responses.[55] By forging the source IP in echo requests, perpetrators directed replies to unsuspecting victims, a tactic integral to smurf attacks and similar floods where the attacker operated "blind" to the target's reactions.[51] This spoofing exploited the stateless nature of early IP routing, lacking source validation, and allowed low-effort deception that evaded basic network protections of the era. Post-2000 ingress filtering recommendations (e.g., RFC 2827) began addressing this, but historical deployments left many networks exposed. Ping's utility also posed reconnaissance risks in the early Internet, where unrestricted responses revealed active hosts and network topologies to potential attackers.[56] Scans using sequential pings across IP ranges identified live devices, aiding subsequent targeted exploits like port scanning or vulnerability probing, as early routers and firewalls often lacked rate limiting or ICMP filtering.[27] This passive information leakage was a foundational step in multi-stage attacks, with the absence of stealth mechanisms in pre-2000s infrastructure amplifying the threat.[57] A notable implementation vulnerability occurred in the ping of death attack, discovered in the mid-1990s, which exploited buffer overflows in IP packet reassembly triggered by oversized or fragmented ICMP echoes.[58] Systems like Windows NT and Windows 95, prior to patches such as Service Pack updates, crashed when attempting to reconstruct packets exceeding the 65,535-byte IPv4 limit, due to inadequate buffer bounds checking in the TCP/IP stack.[59] This flaw affected a wide range of operating systems, including early Microsoft versions without overflow protections, leading to system hangs or reboots from a single malformed ping.[60]Modern Mitigations and Best Practices

To mitigate risks associated with ping usage, modern networks employ firewall rules that selectively block inbound ICMP Echo Requests while permitting necessary replies for diagnostics. For instance, on Linux systems using iptables, administrators can implement rules such asiptables -A INPUT -p icmp --icmp-type echo-request -j DROP to drop unsolicited Echo Requests, reducing exposure to reconnaissance or flood attempts, though outbound replies may still be allowed via corresponding ACCEPT rules for troubleshooting.[61] Similar configurations in tools like firewalld or pfSense enable stateful filtering to ensure only legitimate diagnostic traffic passes.[62]

Rate limiting further protects against ping floods by capping ICMP packet volumes at the operating system and network levels. In Linux kernels, the sysctl parameter net.ipv4.icmp_ratelimit defaults to 1000 messages per second but can be adjusted lower (e.g., via sysctl -w net.ipv4.icmp_ratelimit=100) to throttle responses per destination, preventing resource exhaustion.[63] Routers and edge devices complement this with access control lists (ACLs) for ingress filtering, as recommended in BCP 38 (RFC 2827), which mandates blocking spoofed source addresses to curb amplification attacks originating from external networks.

For IPv6 environments, ICMPv6 requires careful handling to avoid breaking essential functions like path MTU discovery, per RFC 4890 guidelines, which advise firewalls to permit error messages (e.g., Packet Too Big, Time Exceeded) while rate-limiting or blocking non-essential types like Echo Requests unless needed for diagnostics.[64] Additionally, enabling temporary address privacy extensions (RFC 4941) on hosts obscures stable identifiers during ping scans, complicating reconnaissance without impacting core IPv6 operations.

Best practices emphasize authenticated and monitored diagnostics over raw ping usage. Tools like mtr (My Traceroute), which combines ping and traceroute for path analysis, are preferred in secure setups as they provide richer telemetry with built-in rate controls, often run over VPNs to encrypt sensitive probes and avoid exposing internal topologies.[65] Network logs should be routinely scanned for anomalous ping patterns, such as sudden volume spikes indicative of floods, with post-2020 enterprise trends incorporating AI-driven anomaly detection, with machine learning models achieving high accuracies, often over 99% in studies for detecting DDoS attacks including protocol-based ones like ICMP floods.[66]

Recent developments as of 2025 highlight ongoing risks, including a denial-of-service vulnerability in the ping utility of iputils versions before 20250602, exploitable via crafted ICMP Echo Replies, which can cause application errors or incorrect data collection; users should update to patched versions.[67] Additionally, research in February 2025 identified off-path attacks on the TCP/IP suite using forged ICMP error messages to manipulate cross-layer interactions, potentially disrupting connections without direct access.[68] ICMP tunneling has also emerged as a concern for covert data exfiltration or command-and-control, as noted in October 2025 analyses, necessitating deep packet inspection and behavioral monitoring in intrusion detection systems.[69]