Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

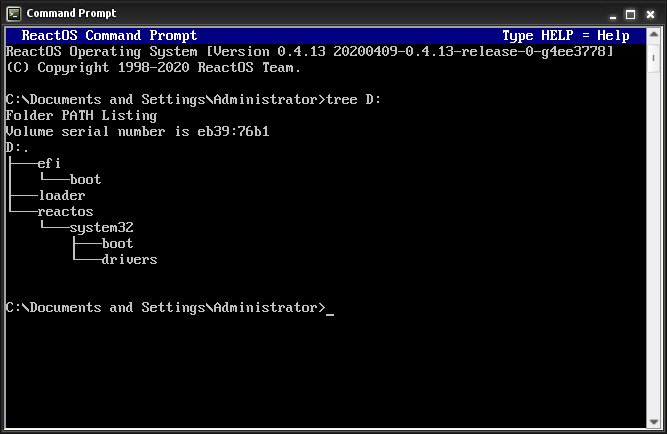

Tree (command)

View on Wikipedia| tree | |

|---|---|

The ReactOS tree command | |

| Developers | Steve Baker, DR, Microsoft, IBM, Itautec, Datalight, Toshiba, Dave Dunfield, Asif Bahrainwala |

| Written in | Unix-like, FreeDOS, ReactOS: C |

| Operating system | Unix, Unix-like, MS-DOS, PC DOS, FlexOS, SISNE plus, ROM-DOS, 4690 OS, PTS-DOS, OS/2, eComStation, ArcaOS, Windows, DR DOS, FreeDOS, ReactOS |

| Platform | Cross-platform |

| Type | Command |

| License | Unix, Unix-like, FreeDOS, ReactOS: GPLv2 |

In computing, tree is a recursive directory listing command or program that produces a depth-indented listing of files. Originating in PC- and MS-DOS, it is found in Digital Research FlexOS,[1] IBM/Toshiba 4690 OS,[2] PTS-DOS,[3] FreeDOS,[4] IBM OS/2,[5] Microsoft Windows,[6] and ReactOS. A version for Unix and Unix-like systems is also available.

The tree command is frequently used as part of a technical support scam, where the command is used to occupy the command prompt screen, while the scammer, pretending to be technical support, types additional text that is supposed to look like output of the command.[7]

Overview

[edit]With no arguments, tree lists the files in the current directory. When directory arguments are given, tree lists all the files or directories found in the given directories each in turn. Upon completion of listing all files and directories found, tree returns the total number of files and directories listed. There are options to change the characters used in the output, and to use color output.[8]

The command is available in MS-DOS versions 3.2 and later and IBM PC DOS releases 2 and later.[9] Digital Research DR DOS 6.0,[10] Itautec SISNE plus,[11] and Datalight ROM-DOS[12] include an implementation of the tree command.

The Tree Command for Linux was developed by Steve Baker.[13] The FreeDOS version was developed by Dave Dunfield[14] and the ReactOS version was developed by Asif Bahrainwala.[15] All three implementations are licensed under the GNU General Public License.

The Tree command is also available in macOS as a formula installed via the command line Homebrew package manager.[16]

Example

[edit]$ tree path/to/folder/

path/to/folder/

├── a-first.html

├── b-second.html

├── subfolder

│ ├── readme.html

│ ├── code.cpp

│ └── code.h

└── z-last-file.html

1 directories, 6 files

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ FlexOS User's Guide (PDF) (Version 1.3 ed.). Digital Research. November 1986. 1073-2003-001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-09-25. Retrieved 2018-09-16.

- ^ "Users Guide". archive.org.[dead link]

- ^ "PTS-DOS 2000 Pro User Manual" (PDF). Buggingen, Germany: Paragon Technology GmbH. 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-12. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- ^ "FreeDOS group -- FreeDOS Base". FreeDOS on ibiblio.org.

- ^ "JaTomes Help - OS/2 Commands". Archived from the original on 2019-04-14. Retrieved 2019-07-27.

- ^ "Tree". Microsoft Docs. 3 February 2023.

- ^ "The World of the Technical Support Scam". The State of Security. 2016-11-09. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

- ^ – Linux User Commands Manual

- ^ Wolverton, Van (2003). Running MS-DOS Version 6.22 (20th Anniversary Edition), 6th Revised edition. Microsoft Press. ISBN 0-7356-1812-7.

- ^ DR DOS 6.0 User Guide Optimisation and Configuration Tips

- ^ Itautec (2015-05-14). "SISNE plus - Referência Sumária" [SISNE plus - Quick Reference Manual]. Datassette (in Portuguese). COD 23987-01-4. Archived from the original on 2019-09-28. Retrieved 2020-01-12. [1] (86 pages)

- ^ "Datalight ROM-DOS User's Guide" (PDF). www.datalight.com.

- ^ Baker, Steve. "Home - Old Man Programmer". Retrieved 2024-01-26.

- ^ "FreeDOS Package -- Tree (FreeDOS Base)". FreeDOS on ibiblio.org.

- ^ tree.c on GitHub

- ^ "Homebrew - Tree (Formala)". Homebrew. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

Further reading

[edit]- Cooper, Jim (2001). Special Edition Using MS-DOS 6.22, Third Edition. Que Publishing. ISBN 978-0789725738.

- Kathy Ivens; Brian Proffit (1993). OS/2 Inside & Out. Osborne McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0078818714.

- John Paul Mueller (2007). Windows Administration at the Command Line for Windows Vista, Windows 2003, Windows XP, and Windows 2000. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470165799.

External links

[edit]Tree (command)

View on Grokipediatree command is a recursive directory listing program available in Unix-like operating systems, including Linux and macOS, that produces a depth-indented listing of files and directories in a hierarchical, tree-like format to visualize the structure of a file system.[1] Versions are also available for Windows and other systems. It displays contents starting from the current directory by default or a specified path, showing symbolic links with their target paths and optionally colorizing output based on the LS_COLORS environment variable when directed to a terminal.[1] Key features include options to include hidden files (via -a), limit recursion depth (via -L), exclude patterns (via -I), follow symbolic links (via -l), and generate alternative outputs such as HTML (-H), XML (-X), or JSON (-J), making it useful for documentation, debugging, and project overviews.[1] Additionally, it supports human-readable file sizes (-h), directory size reporting akin to the du command (--du), and integration with Git ignore files (--gitignore) for filtered listings.[1] Developed by Steve Baker and first released in 1996, the command originated as a Unix/Linux port inspired by earlier DOS utilities, with ongoing maintenance adding support for charsets, OS/2, and modern formats; the stable version as of November 2024 is 2.2.1.[2][3][4]

Introduction

Purpose and Functionality

The tree command is a recursive directory listing program that produces a depth-indented listing of files and directories, presenting the contents in a hierarchical format that visually represents the directory structure.[5] This approach allows users to see the organization of files and subdirectories at a glance, with indentation indicating nesting levels.[6] Its primary function is to traverse and display the structure of a directory tree starting from the current working directory or a specified path, recursively listing all entries while providing counts of files and directories encountered, along with a total summary upon completion.[5] By default, it omits hidden files but can be configured to include them, and it supports colorized output for enhanced visibility when directed to a terminal.[1] A key benefit of the tree command is its improved readability compared to flat, linear listings from commands likels, as it mimics a tree diagram to clearly delineate parent-child relationships in the filesystem.[7] This visualization aids in quickly grasping complex directory hierarchies without manual parsing of output.[8]

The command proves valuable in system administration for mapping filesystem layouts, in debugging to inspect project directories and locate files, and in file exploration to navigate and understand intricate folder organizations efficiently.[8][9]

Availability Across Systems

Thetree command is widely available across Unix-like operating systems, where it is typically provided as a standalone package rather than part of core utilities. In Linux distributions, such as those based on Debian or Ubuntu, it can be installed via the Advanced Package Tool (APT) with the command sudo apt install tree, making it accessible on most major distributions including Fedora and Arch Linux through equivalent package managers like DNF or Pacman.[10][11] In BSD variants, including FreeBSD and NetBSD, the command is available through their package collection systems; for instance, FreeBSD users can install it via pkg install tree, while NetBSD provides it in the pkgsrc tree under sysutils/tree.[12][13]

On macOS, the tree command is not included natively but can be added using third-party package managers. Homebrew users can install it with brew install tree, which pulls from the official formula repository and supports colorized output if environment variables like LS_COLORS are set.[14] Similarly, the Fink package manager offers it via fink install tree, providing compatibility for users preferring Debian-style packaging on macOS.[15] For source-based installations across these platforms, users can download and compile from repositories such as the GitLab-hosted Unix tree project.[16]

In Windows environments, the tree command is built-in to the Command Prompt starting from Windows NT and remains available in all subsequent versions, including Windows 11, allowing graphical display of directory structures directly via tree or tree /F to include files.[17] It functions identically in PowerShell, where it inherits the Command Prompt's implementation without requiring additional modules.[18] For enhanced features aligning with Unix-like systems, third-party ports such as the tree command are available through projects like GnuWin32, installable via binaries or compilation.[19]

The command also appears in legacy and compatible systems. It was introduced in MS-DOS version 3.2 and later, as well as in PC-DOS from version 2 onward, enabling directory visualization on early IBM PC-compatible machines.[20] FreeDOS, an open-source MS-DOS-compatible kernel, includes the tree command in its core utilities for running classic DOS applications.[21] ReactOS, an open-source operating system aiming for Windows NT compatibility, incorporates the tree command as part of its command-line tools.[22]

Open-source implementations of the tree command, including the widely used version by Steve Baker, are distributed under the GNU General Public License version 2 or later (GPLv2+), ensuring free redistribution and modification while requiring source code availability for derivatives.[14][23]

History

Origins in DOS Environments

The tree command originated as an external utility in IBM PC-DOS version 2.0, released in March 1983, and was later incorporated into MS-DOS version 3.2 in 1986.[24][25] Designed for early personal computers using the File Allocation Table (FAT) file system, it addressed the need to visualize the newly introduced hierarchical directory structures, which allowed files to be organized into subdirectories beyond the flat root directory of prior versions.[26] This innovation in PC-DOS 2.0 and MS-DOS 2.0 enabled users to manage increasingly complex file systems on hard drives and floppy disks, making the tree command a practical tool for command-line navigation in text-based environments. The command's primary purpose was to render a graphical, indented representation of the directory hierarchy in ASCII text, mimicking the branching structure of a tree to illustrate parent-child relationships between directories and drives.[25] Inspired by the tree-like organization inherent to the FAT file system's support for nested directories, it provided a quick overview starting from a specified drive or path, typically emphasizing the root directory and its immediate branches.[24] In its initial implementations, the output was limited to directory names only; the /F switch, introduced with the command, included files, though in PC-DOS versions prior to 3.1, it did not list files in the root directory due to a limitation.[25] Early versions of the tree command exhibited several limitations suited to the constraints of 1980s hardware and software. It produced plain text output without color coding, graphical enhancements, or filtering capabilities, relying solely on basic indentation and symbols for structure.[25] Functionality was restricted to local drives, excluding network volumes or those altered by commands like ASSIGN, JOIN, or SUBST, and it required a separate executable file (TREE.COM or TREE.EXE) to run.[25] These constraints focused its utility on simple, local file system inspections, particularly from the root directory of bootable drives.[24] The simplicity and effectiveness of the DOS tree command in rendering file system hierarchies within resource-limited command-line interfaces influenced its adaptation to other operating systems, including Unix-like environments in the late 1980s and beyond.[24] Its straightforward approach to recursive directory listing became a foundational model for similar utilities, prioritizing clarity in text-mode displays over advanced features.[25]Development for Unix-like Systems

The initial port of the tree command to Unix-like systems was developed by Steve Baker in 1996 as a Linux utility designed to replicate the functionality of the DOS tree command.[3] This version 1.0 provided a basic recursive directory listing in a tree-like format, filling a gap in early Linux tools for visual file system navigation.[27] Key milestones in its evolution include the release of version 1.0 in 1996, followed by enhancements in subsequent versions such as the addition of color support via integration with the LS_COLORS environment variable (similar to dircolors) and autotools for easier building in forks like that maintained by Neil Stevens.[28] Ongoing maintenance has occurred through community-driven repositories, culminating in version 1.8.0 in 2018 and continuing with the official project to version 2.2.1 as of November 2024, incorporating improvements like better Unicode handling in UTF-8 locales.[27][29][16] The project shifted to the GPLv2 license to facilitate open-source contributions and distribution. It has been integrated into package repositories of major Unix-like distributions, including Debian (where it is maintained as a standard utility package) and Red Hat/Fedora ecosystems, ensuring widespread availability across Linux environments.[29] Further enhancements include support for Unicode filenames when using UTF-8 encoding, display of extended file attributes through symbolic indicators in listings, and colored output integration with tools like dircolors for improved readability on terminals.[30][1] Notable developers contributing to Unix-like implementations include Steve Baker (original author), Thomas Moore, Francesc Rocher, Florian Sesser, and Kyosuke Tokoro, who added features like HTML output and charset support; community ports by Dave Dunfield (FreeDOS adaptation with Unix influences) and Asif Bahrainwala (ReactOS version) have also informed cross-platform compatibility.[27]Syntax and Usage

Basic Command Syntax

The basic syntax of thetree command is tree [options] [directory], where the [options] portion allows for various modifiers (detailed elsewhere) and the [directory] argument specifies the starting point for the listing, which is optional and defaults to the current working directory if omitted.[1][5]

When invoked without arguments, tree recursively scans the current directory and all its subdirectories, producing a depth-indented listing of files and directories in a tree-like format, while terminating recursion at any unreadable directories due to insufficient permissions or access errors.[1] The command requires read permissions on the target directories to traverse and list their contents; lacking these permissions results in those directories being skipped, though the overall process continues for accessible portions of the tree.[5] By default, tree ignores hidden files and directories (those whose names begin with a period .), and it imposes no limit on recursion depth.[1]

In handling file system elements, tree processes symbolic links by displaying the link name followed by an arrow and the target path (e.g., linkname -> target), but it does not follow symbolic links pointing to directories for recursive descent, thereby preventing potential infinite loops from circular links.[5]

Standard Output Format

The standard output of thetree command presents a hierarchical, depth-indented representation of the directory structure, utilizing ASCII line-drawing characters to visually depict branches and connections between directories and files.[1] This format employs symbols such as ├── to indicate continuation of a branch with additional siblings, └── for the final item in a branch, │ for vertical connections, and spaces for indentation to maintain the tree-like appearance, ensuring readability in terminal environments.[1] Directory names are displayed followed by their contents, with subdirectories recursively expanded in the same manner, while files appear at the leaf level without further indentation.[5]

By default, the output lists all non-hidden files and directories within the specified path, excluding those beginning with a dot (.), and concludes with a summary line tallying the total number of directories and files encountered, such as "4 directories, 12 files".[1] This summary provides a quick overview of the scope of the listing, counting only accessible items.[5] For empty directories, the structure still includes the directory name, followed by no further listings, implicitly indicating zero contents without additional notation.[1]

In cases of restricted access, permission-denied directories are indicated by an error message such as [error opening dir], preventing further recursion into inaccessible areas while maintaining the overall tree integrity.[1][31] Symbolic links are handled by displaying them as name -> target_path, where the target is the linked destination, and the command includes built-in cycle detection to avoid infinite loops from circular references by not recursing into detected cycles.[1][5]

The default character set for these line-drawing symbols relies on the system's locale, typically UTF-8 for modern Unix-like systems, which supports the extended ASCII characters; however, this can be overridden for compatibility, though the fundamental tree-like indentation and branching remain unchanged to preserve visual hierarchy.[1]

For illustration, invoking tree on a sample directory might yield:

.

├── dir1

│ └── file1.txt

├── dir2

│ ├── file2.txt

│ └── empty_dir

└── file3.txt

2 directories, 3 files

.

├── dir1

│ └── file1.txt

├── dir2

│ ├── file2.txt

│ └── empty_dir

└── file3.txt

2 directories, 3 files

Options

Display and Formatting Options

The tree command provides several options to customize the visual presentation and structural layout of its directory tree output, allowing users to tailor the display for readability, compatibility, or specific informational needs. These options modify aspects such as inclusion of hidden elements, path rendering, recursion limits, colorization, line drawing styles, file type indicators, indentation, and supplementary metadata like ownership details.[5][32] The -a option includes all files in the output, even hidden ones that begin with a dot (.), while explicitly excluding the special entries '.' (current directory) and '..' (parent directory) regardless of settings.[5] In contrast, the -d option restricts the display to directories only, omitting all files to focus solely on the hierarchical structure of folders.[5] The -f option appends the full absolute path prefix to each file and directory name, which is particularly useful for scripting or when absolute locations are required in the output.[5] To control the depth of recursion, the -L option specifies a maximum display level for the directory tree; for instance, -L 2 limits the traversal to the current directory and one subdirectory level, preventing exhaustive output in deep hierarchies.[5] For enhanced visual distinction, the -C option enables colorized output, leveraging the LS_COLORS environment variable for coloring if set, or falling back to built-in defaults; this aids in quickly identifying file types when piping output or in non-interactive contexts.[5] Line drawing and character set options further adapt the output for different terminals or encodings. The -A option activates ANSI line graphics for indentation lines, producing more refined tree branches using extended ASCII characters.[5] Similarly, the -S option employs ASCII line graphics suitable for console mode fonts, equivalent to the --charset=IBM437 setting, though it is marked for eventual deprecation in favor of explicit charset options.[5] The -F option appends symbolic indicators to entries, such as '/' for directories, '=' for sockets, '*' for executables, and '|' for FIFOs, mirroring the behavior of ls -F to convey file types at a glance.[5] Additional formatting tweaks include the -i option, which suppresses indentation lines to produce a flat, list-like output—often combined with -f for path-based listings without visual hierarchy—and the -g option, which prints the group name (or GID if unavailable) alongside each file's details, adding ownership context to the tree view.[5][32] These options collectively enable precise control over the tree's appearance without altering the underlying content selection.[5]Filtering and Control Options

The tree command provides several options for filtering the traversal of directory structures, incorporating metadata into the output, and controlling the destination and suppression of certain elements in the display.Filtering Options

The-P option limits the output to only those files and directories that match a specified shell-style wildcard pattern, effectively pruning the traversal to focus on relevant items.[5] For instance, invoking tree -P "*.c" displays solely C source files and their containing directories, while patterns support wildcards like *, ?, and [abc].[5] This requires the -a flag to include hidden files matching the pattern.[1]

In contrast, the -I option excludes files and directories matching the wildcard pattern from the output, allowing users to skip unwanted elements without altering the overall structure.[5] For example, tree -I "*.o|*.log" ignores object files and log files, using the | operator to combine multiple patterns.[1] Multiple patterns can be specified in a single invocation, separated by |, to refine the exclusion criteria efficiently.[6]

Additionally, the --gitignore option causes tree to omit files listed in .gitignore and .git/info/exclude files when traversing Git repositories, providing filtered output aligned with version control practices.[1]

Metadata Display Options

To augment the tree output with file attributes, the-u option appends the owner username (or UID if the name is unavailable) for each entry.[5] This is useful for auditing permissions in shared environments, as in tree -u which lists owners alongside paths.[1]

The -s option includes the size of each file in bytes, providing a quick overview of storage usage without delving into detailed listings.[5] The -h option prints the size of each file in human-readable units such as KB, MB, or GB (e.g., tree -h shows "4.0K").[1]

Additionally, the -D option prints the last modification timestamp for each file, formatted according to the system's locale, enabling chronological analysis of directory contents.[5] An example usage like tree -D integrates dates directly after file sizes or names.[1]

The --du option reports the apparent size of each directory, including subdirectories, in a manner similar to the du -sh command, offering a summary of disk usage at each level.[1]

Output Control Options

Output redirection is handled by the-o option, which writes the tree structure to a specified file rather than standard output, facilitating scripting or logging.[5] For instance, tree -o structure.txt saves the listing for later review without console clutter.[6]

The --noreport option suppresses the summary line at the end of the output, which normally reports the total number of files and directories scanned.[5] This is particularly helpful in automated pipelines where only the structural data is needed, as in tree --noreport > output.[1]

For web-oriented use, the -H option generates HTML-formatted output with hyperlinks relative to a base URL, transforming the directory tree into a navigable web page.[5] Specifying tree -H http://example.com/base creates an index.html file with FTP or HTTP links to files.[6]

The -X option produces XML-formatted output for structured data representation, while the -J option generates JSON output, both useful for programmatic processing or integration with other tools.[1]

Traversal Control

The-x option restricts the traversal to the same filesystem as the starting directory, preventing the command from crossing mount points or symbolic links to other volumes.[5] This avoids expansive listings in multi-disk setups, such as tree -x /home which stays within the home partition.[1]

The -l option directs tree to follow symbolic links to directories as if they were actual directories, allowing traversal into linked paths rather than treating them as files.[1]

Examples

Simple Directory Listing

Thetree command, invoked without any options or arguments, generates a recursive listing of the current directory's contents, displaying files and subdirectories in a depth-indented, hierarchical format using connecting lines and symbols.[5] This default behavior provides a visual representation of the directory tree, starting from the root of the specified or current path.[5]

A representative example of the output occurs when running tree in a sample directory such as /home/user, which contains subdirectories docs and photos along with associated files:

.

├── docs

│ ├── file1.txt

│ └── subdir

│ └── file2.doc

└── photos

└── image.jpg

2 directories, 3 files

.

├── docs

│ ├── file1.txt

│ └── subdir

│ └── file2.doc

└── photos

└── image.jpg

2 directories, 3 files

├── for branches, │ for vertical lines, and └── for the last item in a level, culminating in a summary line reporting the total count of directories and files encountered.[5]

This output demonstrates the command's recursive traversal, which explores all subdirectory levels by default to build the complete hierarchy.[7] Hidden files and directories—those prefixed with a dot (e.g., .hidden)—are excluded from the listing unless explicitly included via options.[5]

In practice, this uncomplicated usage serves as an efficient way to gain a rapid, text-based overview of a project's or user's directory organization within the terminal environment, facilitating quick assessments of file layouts without needing additional tools.[11]

Customized Output Examples

Thetree -d -L 1 command restricts output to directories only at the top level, excluding files and any recursion into subdirectories, which is useful for quickly identifying the structure of a directory's immediate children without overwhelming detail in large file systems.[5]

For instance, running tree -d -L 1 in a sample root directory might produce:

.

├── bin

├── etc

├── home

├── lib

├── usr

└── var

5 directories

.

├── bin

├── etc

├── home

├── lib

├── usr

└── var

5 directories

tree -a -C command includes all files, even hidden ones starting with a dot (.), while enabling colorization to distinguish file types visually, such as blue for directories and green for executables, aiding in rapid scanning of comprehensive listings.[5]

An example output from tree -a -C in a user home directory could appear as (with colors indicated in description):

.

├── .bashrc

├── .hidden_config

├── documents/

├── Downloads/

├── [public](/page/Public)/

└── .ssh/

│ └── id_rsa

4 directories, 3 files

.

├── .bashrc

├── .hidden_config

├── documents/

├── Downloads/

├── [public](/page/Public)/

└── .ssh/

│ └── id_rsa

4 directories, 3 files

.bashrc and .ssh are shown in standard color (often white or default), directories in blue, enhancing readability on terminals supporting ANSI colors.[5]

The tree -f -s /path command displays absolute paths for each entry along with file sizes in bytes, which helps in assessing storage usage and locating items precisely within a specified directory path, particularly beneficial for scripting or auditing.[5]

For example, executing tree -f -s /home/user/docs might yield:

/home/user/docs

├── /home/user/docs/report.pdf [1024000]

├── /home/user/docs/images/

│ ├── /home/user/docs/images/photo.jpg [204800]

│ └── /home/user/docs/images/chart.png [51200]

└── /home/user/docs/notes.txt [4096]

1 directory, 4 files

/home/user/docs

├── /home/user/docs/report.pdf [1024000]

├── /home/user/docs/images/

│ ├── /home/user/docs/images/photo.jpg [204800]

│ └── /home/user/docs/images/chart.png [51200]

└── /home/user/docs/notes.txt [4096]

1 directory, 4 files

Implementations

Unix-like and Linux Variants

In Unix-like systems, the tree command is implemented as a standalone utility originally developed by Steve Baker, with ongoing maintenance and enhancements available through source distributions and package repositories.[2] The standard version, often simply packaged as "tree," supports core functionality such as recursive directory listings with depth indentation, optional colorization based on the LS_COLORS environment variable, and extensions like HTML output (-H) and human-readable file sizes (-h).[1] In most GNU/Linux distributions, this implementation serves as the default, providing compatibility with POSIX standards while adding Unix-specific features like pattern matching for filtering directories and files.[4] The GNU/Linux variant is widely available through native package managers; for example, on Debian-based systems like Ubuntu, it can be installed viasudo apt install tree, yielding versions such as 2.1.1, which includes advanced options like JSON output (--json) for structured data export, introduced by contributor Florian Sesser. On Red Hat-based distributions like Fedora or CentOS, installation typically requires enabling the EPEL repository followed by sudo dnf install tree or sudo yum install tree, delivering a comparable build optimized for glibc environments.[34] Recent releases, up to version 2.2.1 as of November 2024, incorporate improvements such as support for .gitignore files to skip version-controlled exclusions, enhanced JSON error reporting, and options for directory size totals (--du), making it suitable for scripting and system administration tasks in Linux environments; versions vary by distribution, with upstream at 2.2.1 (no newer release as of November 2025).[4]

BSD variants, such as those in FreeBSD and OpenBSD, utilize a near-identical implementation of Steve Baker's tree, emphasizing portability and minimal dependencies. In FreeBSD, the command is not installed by default but can be added via the ports collection (cd /usr/ports/sysutils/tree && make install clean) or binary packages (pkg install tree), producing output colorized with dircolors if LS_COLORS is set and defaulting to UTF-8 character encoding for tree graphics.[12] These variants align closely with the Linux version in core options but may exhibit minor differences in default behaviors, such as stricter adherence to BSD's locale settings for character sets, ensuring compatibility with ZFS and UFS file systems without additional tweaks. Version alignment is maintained through ports updates, mirroring upstream releases like 2.2.1 for consistent feature parity across BSD systems as of late 2024.[34][35]

On macOS, a Darwin-based Unix variant, tree is not included natively but is readily available via Homebrew, the popular package manager for open-source software, using brew install tree to deploy Steve Baker's implementation.[14] This build supports all standard options, including charset handling for Unicode filenames common in APFS (the successor to HFS+), and integrates seamlessly with macOS's BSD-derived shell environment, though it requires no specific tweaks for legacy HFS+ volumes as it relies on standard POSIX directory traversal. Source compilation is also straightforward using the upstream tarball, allowing customization for Darwin-specific paths, and recent versions up to 2.2.1 provide enhancements like hyperlink support (--hyperlink) for terminal output.[4]

Across these platforms, source builds from the official GitLab repository are common for users seeking the latest features or custom patches, with version history tracking enhancements like prune support for empty directories (since 1.6.0) and improved cross-compilation for embedded Unix-like systems.[16] Package management ensures easy updates, with tools like apt, yum/dnf, and ports handling dependencies such as ncurses for interactive output, promoting widespread adoption in Unix-derived ecosystems.

Windows and DOS Implementations

The tree command originated as an external command in early versions of MS-DOS and PC DOS. In these DOS environments, the command generates a plain text representation of the directory structure starting from a specified drive letter or the current directory, using basic ASCII characters for branching lines without any color support or configurable recursion depth limits, though practical limits were imposed by available memory.[25] Output is limited to accessible directories on the specified drive, reflecting DOS's drive-letter-based file system organization. In the Windows Command Prompt, the tree command has been a native utility in early Windows NT versions, providing a graphical text-based view of directory hierarchies using extended ASCII characters for lines and branches by default.[17] Key options include/F to display full file names alongside directories and /A to substitute standard ASCII characters for extended ones, enabling better compatibility when redirecting output to files or non-graphical environments. Unlike Unix implementations, it lacks options for pattern matching, level limiting, or excluding specific directories, and there are no recursion depth controls, potentially leading to extensive output on large volumes. The command respects NTFS access controls, skipping inaccessible subdirectories without explicit error reporting, which differs from Unix tree's default behavior of indicating permission-denied traversals.

PowerShell does not include a built-in tree equivalent but supports the Windows tree.exe executable directly for compatibility, or enhanced directory visualization through Get-ChildItem -Recurse piped to custom formatting scripts for tree-like output.[36] Third-party installations, such as via Chocolatey package manager or Git Bash (which provides the Unix tree port), extend functionality with additional options like colorization or filtering not native to the Windows version.[18]

Ports of the tree command exist for open-source DOS-compatible systems, including FreeDOS, where developer Dave Dunfield implemented a version supporting basic message catalogs for multilingual output and compilable under GPLv2 licensing.[37] Similarly, ReactOS features a faithful recreation developed by Asif Bahrainwala, emulating Windows behavior with tree.com while incorporating GPLv2 compatibility and limited Unix-like flags for broader portability.[38]

A notable limitation in DOS and early Windows implementations is the lack of native Unicode support, resulting in garbled display or loss of non-ASCII characters in directory names, particularly when redirecting output to files without the /A option to enforce ASCII rendering.[39] In Windows, interactions with NTFS permissions mean the command traverses only accessible paths, potentially omitting parts of the tree without notification, in contrast to Unix variants that may provide more explicit feedback on access issues.[17]

Alternatives

Command-Line Alternatives

Thefind command in Unix-like systems provides recursive directory traversal capabilities, allowing users to search for directories with options like -type d to list only directories starting from the current path (e.g., find . -type d), and -printf for customizing output formats such as paths or metadata.[40] However, it produces a flat list without the indented hierarchical visualization typical of tree-like displays.[41]

On Unix systems, the ls -R option enables recursive listing of files and subdirectories, outputting a simple, non-indented structure that shows contents level by level but lacks visual hierarchy for easier navigation.[42] Similarly, in Windows Command Prompt, dir /s performs a recursive directory listing, including subdirectories and files in a flat format with details like sizes and dates, without any tree indentation.[43]

The ncdu tool offers an interactive, ncurses-based interface for analyzing disk usage, presenting a navigable tree view of directories sorted by size to identify space consumption, though its primary emphasis is on quantitative metrics rather than pure structural representation.[44]

Modern ls replacements like eza (written in Rust) and lsd provide tree-like output via flags such as --tree in eza or the built-in tree view in lsd, incorporating colors, icons, and Git status integration for enhanced readability in terminal environments.[45][46] These tools extend basic listing functionality but integrate tree visualization as an optional feature alongside file details.

Compared to the dedicated tree command, which specializes in static, indented hierarchical views for directory structures, these alternatives prioritize versatility—such as search precision in find, simplicity in ls -R or dir /s, interactivity and size focus in ncdu, or modern aesthetics and integrations in eza and lsd—often at the expense of a singular emphasis on pure tree formatting.[47]