Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

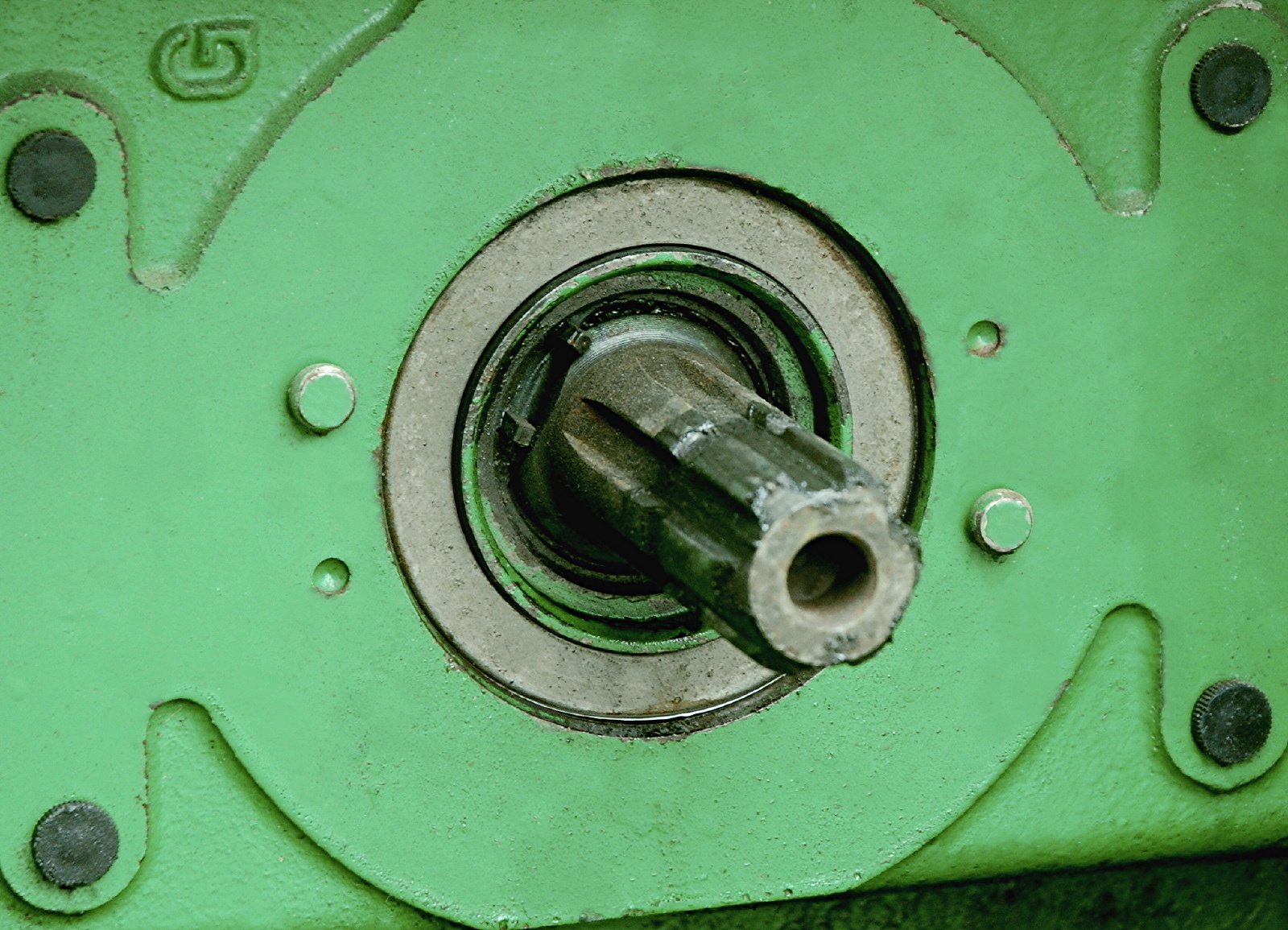

Power take-off

View on Wikipedia

A power take-off or power takeoff (PTO) is one of several methods for taking power from a power source, such as a running engine, and transmitting it to an application such as an attached implement or separate machine.

Most commonly, it is a splined drive shaft installed on a tractor or truck allowing implements with mating fittings to be powered directly by the engine.

Semi-permanently mounted power take-offs can also be found on industrial and marine engines. These applications typically use a drive shaft and bolted joint to transmit power to a secondary implement or accessory. In the case of a marine application, such as shafts may be used to power fire pumps.

In aircraft applications, such an accessory drive may be used in conjunction with a constant speed drive. Jet aircraft have four types of PTO units: internal gearbox, external gearbox, radial drive shaft, and bleed air, which are used to power engine accessories. In some cases, aircraft power take-off systems also provide for putting power into the engine during engine start.[1] See also Coffman starter.

History

[edit]

Various power transmission methods were available before power take-offs became common, but there were applications which would benefit more from some of the attributes that PTOs would provide. Flat belts were generally only useful for applications where the engine was stationary, such as factory steam engines, portable stationary engines, or traction engines parked in front of the work. For moving vehicles such as a traction engine or early tractor towing a farm implement, the implement could receive rotary power by taking it from one of its own wheels (whose turning was imparted by the towing) and distributing it via roller chains (to a sickle bar's crank, for example), but such a transmission ceases if the vehicle stops traveling, and the workload's resistance tends to make the wheel skid rather than turn, even if cleated. The concept of a shaft drive with easily connected and disconnected couplings, and flexibility for driving at changing angles (such as when an articulated tractor-and-trailer combination turns), was a goal to pursue.

Experimental power take-offs were tried as early as 1878, and various homemade versions were constructed over the subsequent decades.[2] International Harvester Company (IHC) was first to market with a PTO on a production tractor, with its model 8-16, introduced in 1918.[3] Edward A. Johnston, an IHC engineer, had been impressed by a homemade PTO that he saw in France about a decade before, improvised by a French farmer and mechanic surnamed Gougis.[3] He and his IHC colleagues incorporated the idea into the 8-16, and designed a family of implements to take advantage of the feature. IHC was not alone in the market for long, as within a year PTOs were appearing on other production tractors, such as some Case models. In 1920, IHC offered the PTO option on their 15-30 tractor, and it was the first PTO-equipped tractor to be submitted for a Nebraska tractor test. The PTO was a competitive advantage for IHC in the 1920s, and other companies eventually caught up with PTO implementation.

Inside the transmission, the exact point along the gear train where the power is taken off determines whether the PTO can be run independently of vehicle travel (ground speed). Early PTOs were often taken off the main output shaft, meaning that the vehicle had to be "in gear" in order to run the PTO. Later this was improved by so-called live PTO (LPTO) designs, which allow control of the PTO rotation independently of the tractor motion. This is an advantage when the load driven by the PTO requires the tractor motion to slow or stop running to allow the PTO driven equipment to catch up. It also allows operations where the tractor remains parked, such as silo-filling or unloading a manure spreader to a pile or lagoon rather than across a field. In 1945, Cockshutt Farm Equipment Ltd of Brantford, Ontario, Canada, introduced the Cockshutt Model 30 tractor with LPTO. Live PTOs eventually became a widespread norm for new equipment; in modern tractors, LPTO is often controlled by push-button or selector switch. This increases safety of operators who need to get close to the PTO shaft.

Safety

[edit]

The PTO, as well as its associated shafts and universal joints, are a common cause of incidents and injury in farming and industry. According to the National Safety Council, six percent of tractor related fatalities in 1997 in the United States involved the PTO. Incidents can occur when loose clothing is pulled into the shaft, often resulting in bone fractures, loss of limbs, other permanent disabilities, or death to its wearer. On April 13, 2009, former Major League Baseball star Mark Fidrych died as a result of a PTO related accident; "He appeared to have been working on his truck when his clothes became tangled in the truck's power take-off shaft", District Attorney Joseph Early Jr. said in a statement.[4] Despite much work to reduce the frequency and severity of agricultural injuries, these events still occur.[5]

Some implements employ light free-spinning protective plastic guards to enshroud the PTO shaft;[6][7] these are mandatory in some countries. [citation needed] In the UK, Health and Safety Executive guidance is contained in a leaflet.[8]

Technical standardization

[edit]Agricultural PTOs are standardized in dimensions and speed. The ISO standard for PTOs is ISO 500,[9] which as of the 2004 edition was split into three parts:

- ISO 500-1 General specifications, safety requirements, dimensions for master shield and clearance zone

- ISO 500-2 Narrow-track tractors, dimensions for master shield and clearance zone

- ISO 500-3 Main PTO dimensions and spline dimensions, location of PTO.

The original type (designated as Type 1) calls for operation at 540 revolutions per minute (rpm). A shaft that rotates at 540 rpm has six splines on it, and a diameter of 1+3⁄8 inches (35 mm).[10]

Two newer types, supporting higher power applications, operate at 1000 rpm and differ in shaft size.[10] Farmers typically differentiate these two types by calling them "large 1000" or "small 1000" as compared to the Type 1 which is commonly referred to as the "540". All new types (2, 3, and 4) use involute splines, whereas Type 1 uses straight splines.[9]

Inch-denominated shafts are round, rectangular, square, or splined; metric shafts are star, bell, or football-shaped.[11]

| Type | RPM | Diameter | Splines |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 540 | 1+3⁄8 in or 35 mm | 6 straight |

| 2 | 1,000 | 1+3⁄8 in or 35 mm | 21 involute |

| 3 | 1,000 | 1+3⁄4 in or 44 mm | 20 involute |

| 4 | 1,300 | 57.5 millimetres (2.26 in) | 22 involute |

Due to ever-increasing horsepower requirements from farm implements, and higher horsepower engines being installed in farm tractors, a still larger type (designated as Type 4) has been added to ISO 500. It operates at a higher rotational speed of 1300 rpm in order to allow for power transfer at reduced levels of torque. The shaft has 22 splines with a major diameter of 57.5 millimeters (mm). It is meant to handle PTO powers up to 450 kilowatts (kW), or roughly 600 horsepower (hp).

All four types rotate counterclockwise when viewed looking back from inside the tractor's cab; when standing behind the tractor and looking directly at the shaft, it turns clockwise.[10]

A 10-spline type was used with some early equipment such as the 1948 Land Rover. A six-spline adapter was usually supplied. It is customary for agricultural machines manufacturers to provide the nominal PTO power specification, an indication of the available instantaneous power at the shaft. Newer tractors may come equipped with 540/540E and/or 1000/1000E options that allow the tractor to power certain low-power-demand implements like hay rakes or tedders using lower engine speeds to maintain the revolutions per minute needed, using less fuel and placing less stress on the engine – thereby improving efficiency and reducing costs.

The first industry standard for PTO design was adopted by ASAE (the American Society of Agricultural Engineers) in April 1927. The PTO rotational speed was specified as 536 ± 10 rpm; the direction was clockwise. The speed was later changed to 540 rpm.[12]

Use on commercial vehicles

[edit]

Truck transmissions have one or more locations which allow for a PTO to be mounted. The PTO must be purchased separately and care is required to match the physical interface of the transmission with a compatible PTO. PTO suppliers will usually require details of the make, model and even serial number of the transmission. Care is also needed to ensure that the physical space around the transmission allows for installation of the PTO. The PTO is engaged and disengaged using the main transmission clutch and a remote control mechanism which operates on the PTO itself. Typically, an air valve is used to engage the PTO, but a mechanical linkage, electric or hydraulic mechanism are also options.

Most Unimogs come with front and/or rear PTOs and hydraulics as well as three point hitch systems.

Units will be rated according to the continuous and intermittent torque that can be applied through them and different models will offer different "PTO shaft rotation to engine RPM" ratios.

In the majority of cases, the PTO will connect directly to a hydraulic pump. This allows for transmission of mechanical force through the hydraulic fluid system to any location around the vehicle where a hydraulic motor will convert it back into rotary or linear mechanical force. Typical applications include:

- Running a water pump on a fire engine or water truck

- Running a truck mounted hot water extraction machine for carpet cleaning (driving vacuum blower and high-pressure solution pumps)

- Powering a blower system used to move dry materials such as cement

- Powering a vehicle-integrated air compressor system[13]

- Raising a dump truck bed

- Operating the mechanical arm on a bucket truck used by electrical maintenance personnel or cable TV maintenance crews

- Operating a winch on a tow truck

- Operating the compactor on a garbage truck

- Operating a Boom/Grapple truck

- Operating a truck mounted tree spade and lift-mast assembly

Split shaft

[edit]A split shaft PTO is mounted to the truck's drive shaft to provide power to the PTO. Such a unit is an additional gearbox that separates the vehicle's drive shaft into two parts:

- The gearbox-facing shaft which will transmit the power of the engine to the split shaft PTO;

- The axle-facing shaft which transmit the propelling power to the axle.

The unit itself is designed to independently divert the engine's power to either the axle-facing shaft or the additional PTO output shaft. This is done by two independent clutches like tooth or dog clutches, which can be operated at total driveline standstill only. Because the main gearbox changes the rotation speed by selection of a gear, the PTO cannot be operated while the vehicle is moving.

On 4x4 vehicles, only the rear drive shaft is used by the split shaft PTO gearbox, requiring the vehicle's 4x4 drive scheme to be of the selectable 4WD type to keep the front axle drive shaft completely decoupled during PTO operation.

It is also possible to connect something other than a hydraulic pump directly to the PTO: for example, fire truck pumps.

"Sandwich" split shaft

[edit]A "sandwich" type split shaft unit is mounted between engine and transmission and used on road maintenance vehicles, fire fighting vehicles and off-road vehicles. This unit gets the drive directly from the engine shaft and can be capable of delivering up to the complete engine power to the PTO. Usually these units come with their own lubricating system. Due to the sandwich mounting style, the gearbox will be moved away from the engine, requiring the driveline to accommodate the installation.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ NASA Technical Memorandum 101731; Monitoring Techniques for "X-29A Aircraft's High Speed Rotating Power Takeoff Shaft"; David F Voracek, Ames Research Center, Dryden Flight Research Facility, Edwards, California, December 1990 nasa.gov

- ^

Quick, Graeme (March–April 2008). "Spinning an historical yarn about power-take-off shafts" (PDF). Australian Grain. 17 (6). Greenmount Press: 36–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-02-26. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

[From p. 36] The medal for the first recorded power take-off on a piece of mobile machinery on the other hand ought to go to an Aveling and Porter Bell-type reaper. This steam-powered outfit was put on show at the 1878 Universal Exposition in Paris.

- ^ a b Pripps & Morland 1993, pp. 37–39.

- ^ "Examiner: Fidrych suffocated to death". ESPN.com. 16 April 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Tinc, Pamela J.; Sorensen, Julie A. (2019-01-02). "Marketing Farm Safety: Using Principles of Influence to Increase PTO Shielding". Journal of Agromedicine. 24 (1): 101–109. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2018.1539421. ISSN 1059-924X. PMC 6353692. PMID 30346257.

- ^ "Power-Take-Off (PTO) Safety" (PDF). National Safety Council. May 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-28. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^

Privette, Charles (2002-03-01). "Farm Safety & Health - PTO Safety". Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. Clemson University. Archived from the original on 2005-03-28. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

shields and guards were developed to prevent injury from these rotating shafts

- ^ "Agriculture Information Sheet No 40 (AIS40). Power take-offs and power take-off drive shafts" (PDF). Health and Safety Executive UK. October 2013 [January 2013]. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-31. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ a b c International Standard (April 1, 2014). "Agricultural tractors - Rear-mounted power take-off types 1, 2, 3 and 4" (PDF). International Standard. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Equipment Hub: Understanding power takeoff drivelines - Progressive Forage | Ag Proud".

- ^ "The Different Types of PTO Shafts". 15 February 2021.

- ^ Goering, Carroll; Cedarquist, Scott (October 2004). "Last Word: Why 540?" (PDF). Resource Magazine. Vol. 11, no. 8. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers. p. 29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ^ "PTO Air Compressors | Direct-Transmission™ Mounted Air Compressor". VMAC. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

Bibliography

[edit]- Pripps, Robert N.; Morland, Andrew (photographer) (1993). Farmall Tractors: History of International McCormick-Deering Farmall Tractors. Farm Tractor Color History Series. Osceola, WI: MBI. ISBN 978-0-87938-763-1.