Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Prenatal development

View on Wikipedia

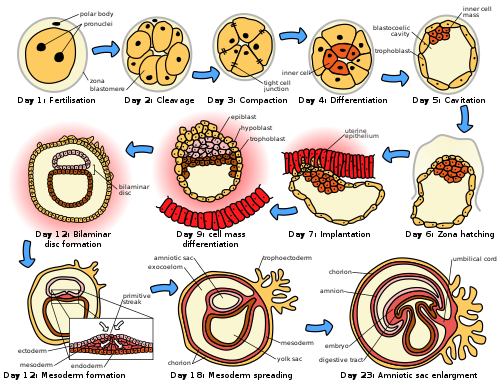

Prenatal development (from Latin natalis 'relating to birth') involves the development of the embryo and of the fetus during a viviparous animal's gestation. Prenatal development starts with fertilization, in the germinal stage of embryonic development, and continues in fetal development until birth. The term "prenate" is used to describe an unborn offspring at any stage of gestation.[1]

In human pregnancy, prenatal development is also called antenatal development. The development of the human embryo follows fertilization, and continues as fetal development. By the end of the tenth week of gestational age, the embryo has acquired its basic form and is referred to as a fetus. The next period is that of fetal development where many organs become fully developed. This fetal period is described both topically (by organ) and chronologically (by time) with major occurrences being listed by gestational age.

The very early stages of embryonic development are the same in all mammals, but later stages of development, and the length of gestation varies.

Terminology

[edit]In the human:

Different terms are used to describe prenatal development, meaning development before birth. A term with the same meaning is the "antepartum" (from Latin ante "before" and parere "to give birth") Sometimes "antepartum" is however used to denote the period between the 24th/26th week of gestational age until birth, for example in antepartum hemorrhage.[2][3]

The perinatal period (from Greek peri, "about, around" and Latin nasci "to be born") is "around the time of birth". In developed countries and at facilities where expert neonatal care is available, it is considered from 22 completed weeks (usually about 154 days) of gestation (the time when birth weight is normally 500 g) to 7 completed days after birth.[4] In many of the developing countries the starting point of this period is considered 28 completed weeks of gestation (or weight more than 1000 g).[5]

Fertilization

[edit]

Fertilization marks the first germinal stage of embryonic development. When semen is released into the vagina, the spermatozoa travel through the cervix, along the body of the uterus, and into one of the fallopian tubes where fertilization usually takes place in the ampulla. A great many sperm cells are released with the possibility of just one managing to adhere to and enter the thick protective layer surrounding the egg cell (ovum). The first sperm cell to successfully penetrate the egg cell donates its genetic material (DNA) to combine with the DNA of the egg cell resulting in a new one-celled zygote. The term "conception" refers variably to either fertilization or to formation of the conceptus after its implantation in the uterus, and this terminology is controversial.

The zygote will develop into a male if the egg is fertilized by a sperm that carries a Y chromosome, or a female if the sperm carries an X chromosome.[6] The Y chromosome contains a gene, SRY, which will switch on androgen production at a later stage leading to the development of a male body type. In contrast, the mitochondrial DNA of the zygote comes entirely from the egg cell.

Development of the embryo

[edit]

Following fertilization, the embryonic stage of development continues until the end of the 10th week (gestational age) (8th week fertilization age). The first two weeks from fertilization is also referred to as the germinal stage or preembryonic stage.[7]

The zygote spends the next few days traveling down the fallopian tube dividing several times to form a ball of cells called a morula. Further cellular division is accompanied by the formation of a small cavity between the cells. This stage is called a blastocyst. Up to this point there is no growth in the overall size of the embryo, as it is confined within a glycoprotein shell, known as the zona pellucida. Instead, each division produces successively smaller cells.

The blastocyst reaches the uterus at roughly the fifth day after fertilization. The blastocyst hatches from the zona pellucida allowing the blastocyst's outer cell layer of trophoblasts to come into contact with, and adhere to, the endometrial cells of the uterus. The trophoblasts will eventually give rise to extra-embryonic structures, such as the placenta and the membranes. The embryo becomes embedded in the endometrium in a process called implantation. In most successful pregnancies, the embryo implants 8 to 10 days after ovulation.[8] The embryo, the extra-embryonic membranes, and the placenta are collectively referred to as a conceptus, or the "products of conception".

Rapid growth occurs and the embryo's main features begin to take form. This process is called differentiation, which produces the varied cell types (such as blood cells, kidney cells, and nerve cells). A spontaneous abortion, or miscarriage, in the first trimester of pregnancy is usually[9] due to major genetic mistakes or abnormalities in the developing embryo. During this critical period the developing embryo is also susceptible to toxic exposures, such as:

- Alcohol, certain drugs, and other toxins that cause birth defects, such as fetal alcohol syndrome

- Infection (such as rubella or cytomegalovirus)

- Radiation from x-rays or radiation therapy

- Nutritional deficiencies such as lack of folate which contributes to spina bifida

Nutrition

[edit]The embryo passes through 3 phases of acquisition of nutrition from the mother:[10]

- Absorption phase: Zygote is nourished by cellular cytoplasm and secretions in fallopian tubes and uterine cavity.[11]

- Histoplasmic transfer: After nidation and before establishment of uteroplacental circulation, embryonic nutrition is derived from decidual cells and maternal blood pools that open up as a result of eroding activity of trophoblasts.

- Hematotrophic phase: After third week of gestation, substances are transported passively via intervillous space.

Development of the fetus

[edit]The first ten weeks of gestational age is the period of embryogenesis and together with the first three weeks of prenatal development make up the first trimester of pregnancy.

From the 10th week of gestation (8th week of development), the developing embryo is called a fetus. All major structures are formed by this time, but they continue to grow and develop. Because the precursors of the organs are now formed, the fetus is not as sensitive to damage from environmental exposure as the embryo was. Instead, toxic exposure often causes physiological abnormalities or minor congenital malformation.

Development of organ systems

[edit]| This article is part of a series on the |

| Development of organ systems |

|---|

Development continues throughout the life of the fetus and through into life after birth. Significant changes occur to many systems in the period after birth as they adapt to life outside the uterus.

Fetal blood

[edit]Hematopoiesis first takes place in the yolk sac. The function is transferred to the liver by the 10th week of gestation and to the spleen and bone marrow beyond that. The total blood volume is about 125 ml/kg of fetal body weight near term.

Red blood cells

[edit]Megaloblastic red blood cells are produced early in development, which become normoblastic near term. Life span of prenatal RBCs is 80 days. Rh antigen appears at about 40 days of gestation.

White blood cells

[edit]The fetus starts producing leukocytes at 2 months gestational age, mainly from the thymus and the spleen. Lymphocytes derived from the thymus are called T lymphocytes (T cells), whereas those derived from bone marrow are called B lymphocytes (B cells). Both of these populations of lymphocytes have short-lived and long-lived groups. Short-lived T cells usually reside in thymus, bone marrow and spleen; whereas long-lived T cells reside in the blood stream. Plasma cells are derived from B cells and their life in fetal blood is 0.5 to 2 days.

Glands

[edit]The thyroid is the first gland to develop in the embryo at the 4th week of gestation. Insulin secretion in the fetus starts around the 12th week of gestation.

Cognitive development

[edit]Electrical brain activity is first detected at the end of week 5 of gestation. Synapses do not begin to form until week 17.[12] Neural connections between the sensory cortex and thalamus develop as early as 24 weeks' gestational age, but the first evidence of their function does not occur until around 30 weeks, when minimal consciousness, dreaming, and the ability to feel pain emerges.[13] REM sleep develops at around 30 weeks and comprises the majority of sleep (up to 80% of total sleep time).[14] The proportion of REM sleep is progressively reduced to 58% by 36–38 weeks.[15]

Initial knowledge of the effects of prenatal experience on later neuropsychological development originates from the Dutch Famine Study, which researched the cognitive development of individuals born after the Dutch famine of 1944–45.[16] The first studies focused on the consequences of the famine to cognitive development, including the prevalence of intellectual disability.[17] Such studies predate David Barker's hypothesis about the association between the prenatal environment and the development of chronic conditions later in life.[18] The initial studies found no association between malnourishment and cognitive development,[17] but later studies found associations between malnourishment and increased risk for schizophrenia,[19] antisocial disorders,[20] and affective disorders.[21]

There is evidence that the acquisition of language begins in the prenatal stage. After 26 weeks of gestation, the peripheral auditory system is already fully formed.[22] Also, most low-frequency sounds (less than 300 Hz) can reach the fetal inner ear in the womb of mammals.[23] Those low-frequency sounds include pitch, rhythm, and phonetic information related to language.[24] Studies have indicated that fetuses react to and recognize differences between sounds.[25] Such ideas are further reinforced by the fact that newborns present a preference for their mother's voice,[26] present behavioral recognition of stories only heard during gestation,[27] and (in monolingual mothers) present preference for their native language.[28] A more recent study with EEG demonstrated different brain activation in newborns hearing their native language compared to when they were presented with a different language, further supporting the idea that language learning starts while in gestation.[29]

Growth rate

[edit]The growth rate of a fetus is linear up to 37 weeks of gestation, after which it plateaus.[10] The growth rate of an embryo and infant can be reflected as the weight per gestational age, and is often given as the weight put in relation to what would be expected by the gestational age. A baby born within the normal range of weight for that gestational age is known as appropriate for gestational age (AGA). An abnormally slow growth rate results in the infant being small for gestational age, while an abnormally large growth rate results in the infant being large for gestational age. A slow growth rate and preterm birth are the two factors that can cause a low birth weight. Low birth weight (below 2000 grams) can slightly increase the likelihood of schizophrenia.[30]

The growth rate can be roughly correlated with the fundal height of the uterus which can be estimated by abdominal palpation. More exact measurements can be performed with obstetric ultrasonography.

Factors influencing development

[edit]Intrauterine growth restriction is one of the causes of low birth weight associated with over half of neonatal deaths.[31]

Poverty

[edit]Poverty has been linked to poor prenatal care and has been an influence on prenatal development. Women in poverty are more likely to have children at a younger age, which results in low birth weight. Many of these expecting mothers have little education and are therefore less aware of the risks of smoking, drinking alcohol, and drug use – other factors that influence the growth rate of a fetus.

Mother's age

[edit]The term advanced maternal age is used to describe women who are over 35 during pregnancy.[32][33] Women who give birth over the age of 35 are more likely to experience complications ranging from preterm birth[33][32][34] and delivery by Caesarean section,[33][34] to an increased risk of giving birth to a child with chromosomal abnormalities such as Down syndrome.[32][34][35] The chances of stillbirth and miscarriage also increase with maternal age as do the chances of the mother suffering from Gestational diabetes or high blood pressure during pregnancy.[32][34] Some sources suggest that health problems are also associated with teenage pregnancy. These may include high blood pressure, low birth weight and premature birth.[36][37] Some studies note that adolescent pregnancy is often associated with poverty, low education, and inadequate family support.[38] Stigma and social context tend to create and exacerbate some of the challenges of adolescent pregnancy.[37]

Drug use

[edit]An estimated 5 percent of fetuses in the United States are exposed to illicit drug use during pregnancy.[39] Maternal drug use occurs when drugs ingested by the pregnant woman are metabolized in the placenta and then transmitted to the fetus. Recent research displays that there is a correlation between fine motor skills and prenatal risk factors such as the use of psychoactive substances and signs of abortion during pregnancy. As well as perinatal risk factors such as gestation time, duration of delivery, birth weight and postnatal risk factors such as constant falls.[40]

Cannabis

[edit]When using cannabis, there is a greater risk of birth defects, low birth weight, and a higher rate of death in infants or stillbirths.[41] Drug use will influence extreme irritability, crying, and risk for SIDS once the fetus is born.[42] Marijuana will slow the fetal growth rate and can result in premature delivery. It can also lead to low birth weight, a shortened gestational period and complications in delivery.[41] Cannabis use during pregnancy was unrelated to risk of perinatal death or need for special care, but, the babies of women who used cannabis at least once per week before and throughout pregnancy were 216g lighter than those of non‐users, had significantly shorter birth lengths and smaller head circumferences.[43]

Opioids

[edit]Opioids including heroin will cause interrupted fetal development, stillbirths, and can lead to numerous birth defects. Heroin can also result in premature delivery, creates a higher risk of miscarriages, result in facial abnormalities and head size, and create gastrointestinal abnormalities in the fetus. There is an increased risk for SIDS, dysfunction in the central nervous system, and neurological dysfunctions including tremors, sleep problems, and seizures. The fetus is also put at a great risk for low birth weight and respiratory problems.[44]

Cocaine

[edit]Cocaine use results in a smaller brain, which results in learning disabilities for the fetus. Cocaine puts the fetus at a higher risk of being stillborn or premature. Cocaine use also results in low birthweight, damage to the central nervous system, and motor dysfunction. The vasoconstriction of the effects of cocaine lead to a decrease in placental blood flow to the fetus that results in fetal hypoxia (oxygen deficiency) and decreased fetal nutrition; these vasoconstrictive effects on the placenta have been linked to the number of complications in malformations that are evident in the newborn.[45]

Methamphetamine

[edit]Prenatal methamphetamine exposure has shown to negatively impact brain development and behavioral functioning. A 2019 study further investigated neurocognitive and neurodevelopmental effects of prenatal methamphetamine exposure. This study had two groups, one containing children who were prenatally exposed to methamphetamine but no other illicit drugs and one containing children who met diagnosis criteria for ADHD but were not prenatally exposed to any illicit substance. Both groups of children completed intelligence measures to compute an IQ. Study results showed that the prenatally exposed children performed lower on the intelligence measures than their non-exposed peers with ADHD. The study results also suggest that prenatal exposure to methamphetamine may negatively impact processing speed as children develop.[46]

Alcohol

[edit]Maternal alcohol use leads to disruptions of the fetus' brain development, interferes with the fetus' cell development and organization, and affects the maturation of the central nervous system. Even small amounts of alcohol use can cause lower height, weight and head size at birth and higher aggressiveness and lower intelligence during childhood.[47] Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder is a developmental disorder that is a consequence of heavy alcohol intake by the mother during pregnancy. Children with FASD have a variety of distinctive facial features, heart problems, and cognitive problems such as developmental disabilities, attention difficulties, and memory deficits.[47]

Tobacco use

[edit]Tobacco smoking during pregnancy exposes the fetus to nicotine, tar, and carbon monoxide. Nicotine results in less blood flow to the fetus because it constricts the blood vessels. Carbon monoxide reduces the oxygen flow to the fetus. The reduction of blood and oxygen flow may result in miscarriage, stillbirth, low birth weight, and premature births.[48] Exposure to secondhand smoke leads to higher risks of low birth weight and childhood cancer.[49]

Infections

[edit]If a mother is infected with a disease, the placenta cannot always filter out the pathogens. Viruses such as rubella, chicken pox, mumps, herpes, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, low birth weight, prematurity, physical malformations, and intellectual disabilities.[50] HIV can lead to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Untreated HIV carries a risk of between 10 and 20 per cent of being passed on to the fetus.[51] Bacterial or parasitic diseases may also be passed on to the fetus, and include chlamydia, syphilis, tuberculosis, malaria, and commonly toxoplasmosis.[52] Toxoplasmosis can be acquired through eating infected undercooked meat or contaminated food, and by drinking contaminated water.[53] The risk of fetal infection is lowest during early pregnancy, and highest during the third trimester. However, in early pregnancy the outcome is worse, and can be fatal.[53]

Maternal nutrition

[edit]Adequate nutrition is needed for a healthy fetus. Mothers who gain less than 20 pounds during pregnancy are at increased risk for having a preterm or low birth weight infant.[54] Iron and iodine are especially important during prenatal development. Mothers who are deficient in iron are at risk for having a preterm or low birth weight infant.[55] Iodine deficiencies increase the risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, and fetal brain abnormalities. Adequate prenatal care gives an improved result in the newborn.[56]

Low birth weight

[edit]Low birth weight increases an infants risk of long-term growth and cognitive and language deficits. It also results in a shortened gestational period and can lead to prenatal complications.

Stress

[edit]Stress during pregnancy can have an impact on the development of the embryo. Reilly (2017) states that stress can come from many forms of life events such as community, family, financial issues, and natural causes. While a woman is pregnant, stress from outside sources can take a toll on the growth in the womb that may affect the child's learning and relationships when born. For instance, they may have behavioral problems and might be antisocial. The stress that the mother experiences affects the fetus and the fetus' growth which can include the fetus' nervous system (Reilly, 2017). Stress can also lead to low birth weight. Even after avoiding other factors like alcohol, drugs, and being healthy, stress can have its impacts whether families know it or not. Many women who deal with maternal stress do not seek treatment. Similar to stress, Reilly stated that in recent studies, researchers have found that pregnant women who show depressive symptoms are not as attached and bonded to their child while it is in the womb (2017).[57]

Environmental toxins

[edit]Exposure to environmental toxins in pregnancy lead to higher rates of miscarriage, sterility, and birth defects. Toxins include fetal exposure to lead, mercury, and ethanol or hazardous environments. Prenatal exposure to mercury may lead to physical deformation, difficulty in chewing and swallowing, and poor motoric coordination.[58] Exposure to high levels of lead prenatally is related to prematurity, low birth weight, brain damage, and a variety of physical defects.[58] Exposure to persistent air pollution from traffic and smog may lead to reduced infant head size, low birth weight, increased infant death rates, impaired lung and immune system development.[59]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Prenate Definition & Meanin". YourDictionary. Retrieved 11 April 2025.

- ^ patient.info » PatientPlus » Antepartum Haemorrhage Last Updated: 5 May 2009

- ^ The Royal Women's Hospital > antepartum haemorrhage Archived 8 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 13 Jan 2009

- ^ Definitions and Indicators in Family Planning. Maternal & Child Health and Reproductive Health. Archived 25 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine By European Regional Office, World Health Organization. Revised March 1999 & January 2001. In turn citing: WHO Geneva, WHA20.19, WHA43.27, Article 23

- ^ Singh, Meharban (2010). Care of the Newborn. p. 7. Edition 7. ISBN 9788170820536

- ^ Schacter, Daniel (2009). "11-Development". Psychology Second Edition. United States of America: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-07-122207-5.

- ^ Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR (1999). "Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy". N. Engl. J. Med. 340 (23): 1796–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199906103402304. PMID 10362823.

- ^ Moore L. Keith. (2008). Before We Are Born: Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-3705-7.

- ^ a b Daftary, Shirish; Chakravarti, Sudip (2011). Manual of Obstetrics, 3rd Edition. Elsevier. pp. 1–16. ISBN 9788131225561.

- ^ "Fetal development: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Illes J, ed. (2008). Neuroethics: defining the issues in theory, practice, and policy (Repr. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-19-856721-9. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015.

- ^

- Harley, Trevor A. (2021). The Science of Consciousness: Waking, Sleeping and Dreaming. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-1-107-12528-5. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- Cleeremans, Axel; Wilken, Patrick; Bayne, Tim, eds. (2009). The Oxford Companion to Consciousness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-19-856951-0. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- Thompson, Evan; Moscovitch, Morris; Zelazo, Philip David, eds. (2007). The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 415–417. ISBN 978-1-139-46406-2. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Nakahara, Kazushige; Morokuma, Seiichi; Maehara, Kana; Okawa, Hikohiro; Funabiki, Yasuko; Kato, Kiyoko (17 May 2022). "Association of fetal eye movement density with sleeping and developmental problems in 1.5-year-old infants". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 8236. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.8236N. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-12330-1. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9114104. PMID 35581284.

- ^ Grigg-Damberger, Madeleine M.; Wolfe, Kathy M. (15 November 2017). "Infants Sleep for Brain". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 13 (11): 1233–1234. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6786. ISSN 1550-9397. PMC 5656471. PMID 28992837.

- ^ Henrichs, J. (2010). Prenatal determinants of early behavioral and cognitive development: The generation R study. Rotterdam: Erasmus Universiteit.

- ^ a b Stein, Z., Susser, M., Saenger, G., & Marolla, F. (1972). Nutrition and mental performance. Science, 178(62),708-713.

- ^ Barker, D. J., Winter, P. D., Osmond, C., Margetts, B., & Simmonds, S. J. (1989). Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet, 2(8663), 577-580.

- ^ Brown, A.S.; Susser, E.S.; Hoek, H.W.; Neugebauer, R.; Lin, S.P.; Gorman, J.M. (1996). "Schizophrenia and affective disorders after prenatal famine". Biological Psychiatry. 39 (7): 551. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(96)84122-9. S2CID 54389015.

- ^ Neugebauer, R., Hoek, H. W., & Susser, E. (1999). Prenatal exposure to wartime famine and development of antisocial personality disorder in early adulthood. Jama, 282(5), 455-462.

- ^ Brown, A. S., van Os, J., Driessens, C., Hoek, H. W., & Susser, E. S. (2000). Further evidence of relation between prenatal famine and major affective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(2), 190-195.

- ^ Eisenberg, R. B. (1976). Auditory Competence in Early Life: The Roots of Communicate Behavior Baltimore: University Park Press.

- ^ Gerhardt, K. J., Otto, R., Abrams, R. M., Colle, J. J., Burchfield, D. J., and Peters, A. J. M. (1992). Cochlear microphones recorded from fetal and newborn sheep. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 13, 226–233.

- ^ Lecaneut, J. P., and Granier-Deferre, C. (1993). "Speech stimuli in the fetal environment", in Developmental Neurocognition: Speech and Face Processing in the First Year of Life, eds B. De Boysson-Bardies, S. de Schonen, P. Jusczyk, P. MacNeilage, and J. Morton (Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishing), 237–248.

- ^ Kisilevsky, Barbara S.; Hains, Sylvia M.J.; Lee, Kang; Xie, Xing; Huang, Hefeng; Ye, Hai Hui; Zhang, Ke; Wang, Zengping (2003). "Effects of Experience on Fetal Voice Recognition". Psychological Science. 14 (3): 220–224. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.02435. PMID 12741744. S2CID 11219888.

- ^ DeCasper, A. J., and Fifer, W. P. (1980). Of human bonding: newborns prefer their mother's voices. Science 208, 1174–1176.

- ^ DeCasper, A. J., and Spence, M. J. (1986). Prenatal maternal speech influences newborns' perception of speech sounds. Infant Behav. Dev. 9, 133–150.

- ^ Moon, C., Cooper, R. P., and Fifer, W. P. (1993). Two-day-olds prefer their native language. Infant Behav. Dev. 16, 495–500.

- ^ May, Lillian; Byers-Heinlein, Krista; Gervain, Judit; Werker, Janet F. (2011). "Language and the Newborn Brain: Does Prenatal Language Experience Shape the Neonate Neural Response to Speech?". Frontiers in Psychology. 2: 222. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00222. PMC 3177294. PMID 21960980.

- ^ King, Suzanne; St-Hilaire, Annie; Heidkamp, David (2010). "Prenatal Factors in Schizophrenia". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 19 (4): 209–213. doi:10.1177/0963721410378360. S2CID 145368617.

- ^ Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J (2005). "4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why?". The Lancet. 365 (9462): 891–900. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(05)71048-5. PMID 15752534. S2CID 20891663.

- ^ a b c d "Advanced Maternal Age". Cleveland Clinic. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 23 November 2024. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Vasiliki, Moragianni, M.D., M.S.C. (25 November 2024). "Advanced Maternal Age". Johns Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Pregnancy after 35: What you need to know". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ "Pregnancy after 35: What are the risks?". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ Taylor, Rebecca Buffum. "Teen Pregnancy: Medical Risks and Realities". WebMD. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Adolescent pregnancy". www.who.int. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ Diabelková1 Rimárová2 Dorko3 Urdzík4 Houžvičková5 Argalášová6, Jana1 Kvetoslava2 Erik3 Peter4 Andrea5 Ľubica6 (8 February 2023). "Adolescent Pregnancy Outcomes and Risk Factors". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 20 (5): 4113. doi:10.3390/ijerph20054113. PMC 10002018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Wendell, A. D. (2013). "Overview and epidemiology of substance abuse in pregnancy". Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology. 56 (1): 91–96. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e31827feeb9. PMID 23314721. S2CID 44402625.

- ^ Lerma Castaño, Piedad Rocio; Montealegre Suarez, Diana Paola; Mantilla Toloza, Sonia Carolina; Jaimes Guerrero, Carlos Alberto; Romaña Cabrera, Luisa Fernanda; Lozano Mañosca, Daiana Stefanny (2021). "Prenatal, perinatal and postnatal risk factors associated with fine motor function delay in pre-school children in Neiva, Colombia". Early Child Development and Care. 191 (16): 2600–2606. doi:10.1080/03004430.2020.1726903. S2CID 216219379.

- ^ a b Fonseca, B. M.; Correia-da-Silva, G.; Almada, M.; Costa, M. A.; Teixeira, N. A. (2013). "The Endocannabinoid System in the Postimplantation Period: A Role during Decidualization and Placentation". International Journal of Endocrinology. 2013 510540. doi:10.1155/2013/510540. PMC 3818851. PMID 24228028.

- ^ Irner, Tina Birk (November 2012). "Substance exposure in utero and developmental consequences in adolescence: A systematic review". Child Neuropsychology. 18 (6): 521–549. doi:10.1080/09297049.2011.628309. PMID 22114955. S2CID 25014303.

- ^ Fergusson, David M.; Horwood, L. John; Northstone, Kate (2002). "Maternal use of cannabis and pregnancy outcome". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 109 (1): 21–27. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01020.x. ISSN 1471-0528. PMID 11843371. S2CID 22461729.

- ^ "The US Opioid Crisis: Addressing Maternal and Infant Health". Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. 29 May 2019.

- ^ Mayes, Linda C. (1992). "Prenatal Cocaine Exposure and Young Children's Development". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 521: 11–27. doi:10.1177/0002716292521001002. JSTOR 1046540. S2CID 72963424.

- ^ Brinker, Michael J.; Cohen, Jodie G.; Sharrette, Johnathan A.; Hall, Trevor A. (2019). "Neurocognitive and neurodevelopmental impact of prenatal methamphetamine exposure: A comparison study of prenatally exposed children with nonexposed ADHD peers". Applied Neuropsychology: Child. 8 (2): 132–139. doi:10.1080/21622965.2017.1401479. PMID 29185821. S2CID 25747787.

- ^ a b Mattson, Sarah N.; Roesch, Scott C.; Fagerlund, Åse; Autti-Rämö, Ilona; Jones, Kenneth Lyons; May, Philip A.; Adnams, Colleen M.; Konovalova, Valentina; Riley, Edward P. (21 June 2010). "Toward a Neurobehavioral Profile of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 34 (9): 1640–1650. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01250.x. ISSN 0145-6008. PMC 2946199. PMID 20569243.

- ^ Espy, Kimberly Andrews; Fang, Hua; Johnson, Craig; Stopp, Christian; Wiebe, Sandra A.; Respass, Jennifer (2011). "Prenatal tobacco exposure: Developmental outcomes in the neonatal period". Developmental Psychology. 47 (1): 153–169. doi:10.1037/a0020724. ISSN 1939-0599. PMC 3057676. PMID 21038943.

- ^ Rückinger, Simon; Beyerlein, Andreas; Jacobsen, Geir; von Kries, Rüdiger; Vik, Torstein (December 2010). "Growth in utero and body mass index at age 5years in children of smoking and non-smoking mothers". Early Human Development. 86 (12): 773–777. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.08.027. ISSN 0378-3782. PMID 20869819.

- ^ Waldorf, K. M. A. (2013). "Influence of infection during pregnancy on fetal development". Reproduction. 146 (5): 151–162. doi:10.1530/REP-13-0232. PMC 4060827. PMID 23884862.

- ^ "World health statistics". World Health Organization. 2014.

- ^ Diav-Citrin, O (2011). "Prenatal exposures associated with neurodevelopmental delay and disabilities". Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 17 (2): 71–84. doi:10.1002/ddrr.1102. PMID 23362027.

- ^ a b Bobić, B; Villena, I; Stillwaggon, E (September 2019). "Prevention and mitigation of congenital toxoplasmosis. Economic costs and benefits in diverse settings". Food and Waterborne Parasitology. 16 e00058. doi:10.1016/j.fawpar.2019.e00058. PMC 7034037. PMID 32095628.

- ^ Ehrenberg, H (2003). "Low maternal weight, failure to thrive in pregnancy, and adverse pregnancy outcomes". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 189 (6): 1726–1730. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(03)00860-3. PMID 14710105.

- ^ "Micronutrient deficiencies". World Health Organization. 2002. Archived from the original on 5 December 1998.

- ^ "What is prenatal care and why is it important?". www.nichd.nih.gov. 31 January 2017.

- ^ Reilly, Nicole (2017). "Stress, depression and anxiety during pregnancy: How does it impact on children and how can we intervene early?". International Journal of Birth & Parent Education. 5 (1): 9–12.

- ^ a b Caserta, D (2013). "Heavy metals and placental fetal-maternal barrier: A mini review on the major concerns". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 17 (16): 2198–2206. PMID 23893187.

- ^ Proietti, E (2013). "Air pollution during pregnancy and neonatal outcome: A review". Journal of Aerosol Medicine and Pulmonary Drug Delivery. 26 (1): 9–23. doi:10.1089/jamp.2011.0932. PMID 22856675.

Further reading

[edit]- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Fetal development

- Moore, Keith L. (1998). The Developing Human (3rd ed.). Philadelphia PA: W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-0-7216-6974-8.

- Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR (June 1999). "Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy". N. Engl. J. Med. 340 (23): 1796–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199906103402304. PMID 10362823.

- Ljunger E, Cnattingius S, Lundin C, Annerén G (November 2005). "Chromosomal anomalies in first-trimester miscarriages". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 84 (11): 1103–7. doi:10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00882.x. PMID 16232180. S2CID 40039636.

- Newman, Barbara; Newman, Philip (10 March 2008). "The Period of Pregnancy and Prenatal Development". Development Through Life: A Psychosocial Approach. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-55341-0.

- "Prenatal Development – Prenatal Environmental Influences – Mother, Birth, Fetus, and Pregnancy." Social Issues Reference. Version Child Development Vol. 6. N.p., n.d. Web. 19 Nov. 2012.

- Niedziocha, Laura. "The Effects of Drugs And Alcohol on Fetal Development | LIVESTRONG.COM." LIVESTRONG.COM – Lose Weight & Get Fit with Diet, Nutrition & Fitness Tools | LIVESTRONG.COM. N.p., 4 Sept. 2011. Web. 19 Nov. 2012. <How To Adult>.

- Jaakkola, JJ; Gissler, M (January 2004). "Maternal smoking in pregnancy, fetal development, and childhood asthma". American Journal of Public Health. 94 (1): 136–40. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.1.136. PMC 1449839. PMID 14713711.

- Gutbrod, T (1 May 2000). "Effects of gestation and birth weight on the growth and development of very low birthweight small for gestational age infants: a matched group comparison". Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 82 (3): 208F–214. doi:10.1136/fn.82.3.F208. PMC 1721075. PMID 10794788.

- Brady, Joanne P., Marc Posner, and Cynthia Lang. "Risk and Reality: The Implications of Prenatal Exposure to Alcohol and Other Drugs ." ASPE. N.p., n.d. Web. 19 Nov. 2012. <Risk and Reality: The Implications of Prenatal Exposure to Alcohol and Other Drugs>.

External links

[edit]- Chart of human fetal development, U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM)

- U.K. Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), regulatory agency overseeing the use of gametes and embryos in fertility treatment and research

- "Child Safety tips: 10 Expert Tips for Keeping Your Kids Safe",

Prenatal development

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Stages

Key Terminology

Zygote refers to the single diploid cell formed immediately upon fertilization of the ovum by a spermatozoon, containing the complete set of 46 chromosomes that determine the genetic blueprint for the developing organism.[6] This initial cell divides rapidly through mitosis during the germinal stage, which spans the first two weeks post-fertilization.[7] Blastocyst denotes the fluid-filled structure formed around day 5-6 after fertilization, consisting of an inner cell mass (which develops into the embryo) surrounded by a trophoblast layer that facilitates implantation into the uterine endometrium.[8] Implantation typically occurs 6-10 days post-fertilization, marking the transition from the germinal to the embryonic stage.[2] Embryo describes the developing human from the third week after fertilization through the eighth week, a period characterized by rapid organogenesis, tissue differentiation, and the establishment of major body systems, during which the structure resembles a curved cylinder with emerging somites and pharyngeal arches.[6] By the end of this stage, foundational organs like the heart, brain, and limbs have begun forming, though the entity measures approximately 3 cm in length.[9] Fetus designates the stage from the ninth week after fertilization until birth, encompassing growth, maturation of organ systems, and acquisition of viability potential, with the organism exhibiting human-like proportions and functional reflexes by the second trimester.[6] This phase, lasting roughly 30 weeks, involves substantial increases in size and weight, culminating in a full-term average of 50 cm and 3.4 kg.[9] Gestational age measures pregnancy duration from the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP), typically totaling 40 weeks or 280 days, whereas fertilization age (or embryonic/fetal age) counts from conception, adding about two weeks to align with gestational timelines used in clinical assessments.[10] This distinction arises because ovulation occurs around day 14 of a standard 28-day cycle, influencing diagnostic and developmental benchmarks.[11] Additional terms include amnion, the membrane enclosing the embryo/fetus in amniotic fluid for protection and nutrient exchange; chorion, the outer membrane contributing to the placenta; and placenta, the discoid organ enabling maternal-fetal exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste via the umbilical cord.[8] These structures emerge during the embryonic period to support sustained development.[7]Overview of Developmental Periods

Prenatal development in humans is divided into three principal periods based on fertilization age: the germinal stage, the embryonic stage, and the fetal stage.[7][8] These divisions reflect distinct phases of cellular division, organ formation, and maturation, with the germinal stage spanning from conception to implantation (approximately 0-2 weeks post-fertilization), the embryonic stage from weeks 3 to 8, and the fetal stage from week 9 until birth at around 38 weeks post-fertilization.[12][2] This timeline uses fertilization age for accuracy, differing from gestational age (measured from the last menstrual period), which adds about 2 weeks and is commonly used in clinical contexts.[7][13] The germinal stage, lasting roughly 14 days, begins with fertilization of the ovum by sperm in the fallopian tube, forming a zygote that undergoes rapid mitotic divisions known as cleavage.[12][2] By day 5-6, the structure becomes a blastocyst, a fluid-filled sphere with an inner cell mass destined to form the embryo and an outer trophoblast layer that aids implantation into the uterine wall around day 7-10.[14][8] This period is marked by high vulnerability to loss, with up to 30-50% of conceptions failing to implant, often due to chromosomal abnormalities.[15] The embryonic stage (weeks 3-8 post-fertilization) involves organogenesis, where the inner cell mass differentiates into the three primary germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—giving rise to all major tissues and organs.[2][8] Key milestones include neural tube formation by week 4, heart beating by week 5, and limb buds appearing by week 6; by week 8, the embryo measures about 3 cm and possesses rudimentary versions of all organ systems, though it remains highly susceptible to teratogens causing congenital defects.[7] This phase establishes the basic body plan, with cellular proliferation focused on structural complexity rather than size increase.[16] The fetal stage, from week 9 to birth, emphasizes growth, refinement of organ function, and deposition of fat and other tissues, with the fetus increasing in length from about 3 cm to 50 cm and weight from 1 g to over 3 kg.[8][9] Viable organ systems mature, such as lung surfactant production by week 24 enabling potential survival outside the womb with medical support, and brain development accelerating in the third trimester.[13][3] Risks shift from malformation to preterm complications, with full-term birth typically at 38-40 weeks post-fertilization, though variability exists due to genetic and environmental factors.[17][18]Fertilization and Germinal Stage

Fertilization Process

Fertilization in humans is the fusion of a haploid sperm cell with a haploid secondary oocyte to form a diploid zygote, initiating prenatal development. This process occurs in the ampulla of the fallopian tube, typically within 12 to 24 hours after ovulation.[19] [20] The secondary oocyte remains viable for about 24 hours post-ovulation, while capacitated sperm can survive up to 5 days in the female reproductive tract.[21] During ejaculation, 40 to 150 million sperm are deposited in the vagina, but only 100 to 200 reach the oocyte due to barriers like cervical mucus and immune factors.[22] [23] Sperm undergo capacitation in the acidic vaginal environment and female tract, which alters their plasma membrane by removing cholesterol and glycoproteins, enhancing motility via hyperactivation and preparing for the acrosome reaction.[20] Motile sperm traverse the cervix, uterus, and enter the fallopian tube, guided by chemical signals, reaching the oocyte surrounded by cumulus cells and the zona pellucida.[19] Binding to zona pellucida glycoproteins triggers the acrosome reaction, an exocytosis event releasing hydrolytic enzymes such as hyaluronidase and acrosin, which digest the corona radiata and create a path through the zona.[20] The acrosome-reacted sperm penetrates the zona and contacts the oocyte plasma membrane (oolemma), where specific proteins facilitate membrane fusion, allowing the sperm nucleus and centriole to enter the ooplasm.[20] Fusion activates the oocyte, completing meiosis II to extrude the second polar body and form the female pronucleus.[20] To prevent polyspermy, a fast block via oolemma depolarization repels additional sperm, while the primary slow block involves cortical granule exocytosis; these granules release enzymes that cleave zona proteins ZP2 and ZP3, hardening the zona and inhibiting further sperm binding or penetration.[20] The male and female pronuclei then decondense, migrate, and fuse in syngamy, restoring the diploid chromosome set and forming the zygote nucleus.[20] The sperm centriole organizes the first mitotic spindle, enabling cleavage divisions to begin approximately 24 hours post-fertilization.[20] The entire fertilization sequence completes within 24 hours, with the zygote retaining the zona pellucida until implantation.[20]Cleavage and Blastocyst Formation

Following fertilization, the zygote undergoes cleavage, a series of rapid mitotic divisions that partition the cytoplasm into progressively smaller blastomeres without an increase in overall embryo size.[24] These divisions begin approximately 24 hours post-fertilization, yielding the 2-cell stage, followed by subsequent cleavages to the 4-cell stage around 36-40 hours and the 8-cell stage by day 3.[25] Blastomeres at early stages are totipotent, capable of contributing to all embryonic lineages, with embryonic genome activation occurring during the transition from 4- to 8-cell stage.[24] By the 8- to 16-cell stage, around day 3 to 4, the embryo compacts into a morula, a solid ball of tightly adhered cells mediated by E-cadherin-dependent cell-cell adhesion and actomyosin cytoskeleton dynamics.[24] Compaction initiates cell polarization, distinguishing outer cells destined for trophectoderm (TE) from inner cells that form the precursors of the inner cell mass (ICM).[24] The morula, typically comprising 16-32 cells, reaches this stage by day 4 post-fertilization.[25] Blastocyst formation follows on days 4 to 5, as TE cells actively transport fluid via sodium-potassium ATPase pumps, creating the blastocoel cavity through cavitation.[25] The resulting blastocyst structure consists of an outer layer of TE cells, which will contribute to placental tissues; a fluid-filled blastocoel; and the ICM, a cluster of cells at one pole that gives rise to the embryo proper.[24] By day 5-6, the blastocyst expands, often containing 50-200 cells, and may hatch from the zona pellucida by day 6-7, facilitating implantation.[25] In vitro studies confirm these dynamics, highlighting human-specific lineage segregation during this transition.[26]Implantation

Implantation refers to the process by which the blastocyst attaches to and embeds within the endometrium of the uterus, marking the transition from the germinal stage to embryonic development. This occurs approximately 6 to 10 days after fertilization, corresponding to days 20 to 24 of a typical 28-day menstrual cycle, with the uterine endometrium achieving receptivity about 6 to 8 days post-ovulation under progesterone influence.[27][2] The blastocyst, having formed from cleavage divisions, must first hatch from its protective zona pellucida shell upon entering the uterine cavity, a process facilitated by enzymatic activity and typically completed by day 5 to 6 post-fertilization.[2][19] Uterine preparation for implantation involves endometrial transformation into a receptive state, known as the implantation window, driven by rising progesterone levels from the corpus luteum, which induce glandular secretion, stromal edema, and decidualization—the differentiation of stromal cells into decidual cells that support nutrient exchange and immune modulation.[28][29] This window lasts roughly 4 days, during which molecular signals like integrins and cytokines on the endometrial surface align with blastocyst ligands, such as L-selectin, enabling initial contact; misalignment often results in implantation failure, contributing to early pregnancy loss in up to 30-50% of conceptions.[27][30] The implantation sequence unfolds in distinct phases: apposition, where the blastocyst loosely contacts the endometrial epithelium; adhesion, involving tighter binding via adhesion molecules; and invasion, where trophoblast cells of the blastocyst's outer layer penetrate the endometrial basement membrane.[31][32] In humans, implantation is interstitial, with the entire blastocyst embedding deeply into the compacta layer of the endometrium, unlike superficial attachment in some mammals; the trophoblast differentiates into syncytiotrophoblast, which secretes human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) to maintain the corpus luteum, and cytotrophoblast, which proliferates to form primary chorionic villi.[27][33] Successful invasion establishes the uteroplacental interface, but aberrant implantation, such as ectopic attachment outside the uterus (occurring in 1-2% of pregnancies), can lead to life-threatening complications due to failed vascular support.[34][2]Embryonic Development

Timeline and Major Milestones

The embryonic period extends from week 3 to week 8 post-fertilization, a phase dominated by organogenesis where foundational structures of all major organ systems differentiate from the three germ layers established during gastrulation.[16] This stage is critical, as disruptions can lead to congenital anomalies due to the rapid cellular proliferation and differentiation.[3] Week 3: Gastrulation commences around day 16, forming the trilaminar embryonic disc with ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm layers; the neural groove and folds emerge by day 18, initiating neurulation; heart tubes begin fusing by day 21, with 1-3 somite pairs visible.[16] The embryo measures approximately 1-2 mm in length.[16] Week 4: Neural folds fuse to form the neural tube by day 22; the heart tube begins beating around day 23; the rostral neuropore closes on day 24, followed by thyroid primordium thickening on day 25; the caudal neuropore closes by day 28, with about 30 somite pairs formed and the hepatic diverticulum initiating liver development.[16] Limb buds start appearing, and optic primordia develop; crown-rump length (CRL) reaches 2.5-6 mm.[16] Week 5: Upper and lower limb buds elongate; heart septation progresses; lung buds form from the respiratory diverticulum; lens placodes indent to form optic cups.[16] Nasal placodes thicken, and the embryo's CRL is 5-9 mm.[16] Week 6: Upper limb buds rotate and elongate; digital rays form in hands; heart outflow tract septates into aorta and pulmonary trunk; pituitary stalk and adrenal cortex primordia develop; lung descent into thorax begins; midgut herniation occurs through the umbilicus.[3][16] CRL measures 8-11 mm.[16] Week 7: Limb bones initiate endochondral ossification; eyelids begin forming; pancreas fuses and secretes hormones; facial features like nostrils and outer ears refine; stomach and liver enlarge rapidly.[3][16] CRL is 11-14 mm.[16] Week 8: Fingers and toes lengthen and separate; intestines return from herniation after rotation; external ears, nose, and eyelids fully form, with eyelids covering eyes; the embryo straightens from its C-shape, resembling a miniature human form with all major organs present; CRL reaches 18-31 mm.[3][16] By the end of this week, the groundwork for all body systems is laid, marking the transition to the fetal period.[3]Organogenesis and Tissue Differentiation

Organogenesis encompasses the initial formation of major organs from the three primary germ layers established during gastrulation, spanning approximately weeks 3 through 8 post-fertilization. Gastrulation, commencing around day 16 after fertilization, reorganizes the bilaminar embryonic disc into a trilaminar structure comprising ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm through cellular invagination and migration.[35] This period marks heightened vulnerability to teratogens, as disruptions can lead to congenital malformations due to the rapid differentiation of foundational structures.[3] Tissue differentiation proceeds via hierarchical processes involving transcriptional regulation, cell-cell signaling, and morphogen gradients that specify cell fates within each germ layer. For instance, the ectoderm gives rise to neuroectoderm, which forms the neural tube by day 28, precursor to the brain and spinal cord, while surface ectoderm differentiates into epidermis, hair follicles, and glands.[35] Mesodermal tissues emerge from somites (segmented blocks appearing by week 4), differentiating into skeletal muscles, vertebrae, and dermis; intermediate mesoderm forms nephrons and gonads; and lateral plate mesoderm contributes to the cardiovascular system, including the heart tube that begins pulsatile contractions around day 22.[3] Endoderm differentiates into epithelial linings of the respiratory and digestive tracts, as well as associated organs such as the liver, pancreas, and thyroid, with foregut and hindgut regions specified by week 4 through Hox gene expression patterns.[35] Key organogenic milestones include limb bud initiation (upper limbs at day 26, lower at day 28), optic and otic vesicle formation by week 4, and palate fusion between weeks 6 and 9, though the core organogenesis concludes by week 8 when major systems are rudimentary but present.[3] Neural crest cells, delaminating from the ectoderm-neuroectoderm border around week 4, migrate to form diverse structures including peripheral nerves, melanocytes, and craniofacial bones, underscoring the role of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in differentiation.[24]| Germ Layer | Major Derivatives |

|---|---|

| Ectoderm | Central and peripheral nervous systems, epidermis, lens of eye, enamel of teeth[35] |

| Mesoderm | Skeletal and cardiac muscle, bones, blood vessels, kidneys, gonads[3] |

| Endoderm | Epithelial lining of gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, liver, pancreas, thyroid[35] |

Placental and Umbilical Development

The placenta develops from the interaction between fetal trophoblast cells derived from the outer layer of the blastocyst and maternal endometrial tissues of the decidua basalis.[36][37] Implantation begins around day 6 post-fertilization, when the blastocyst, consisting of 32-64 cells, hatches from the zona pellucida and attaches to the endometrial epithelium.[36] By days 7-8, the trophoblast differentiates into two layers: the inner cytotrophoblast, composed of mononucleated proliferating cells, and the outer syncytiotrophoblast, a multinucleated layer that invades and erodes maternal capillaries to form lacunae filled with maternal blood, establishing early uteroplacental circulation by the end of week 2.[38][36] In week 3, cytotrophoblast cells protrude into the syncytiotrophoblast to form primary chorionic villi, which are soon invaded by extraembryonic mesoderm to create secondary villi; embryonic blood vessels then develop within these, forming tertiary villi that branch extensively and connect to the embryonic circulation via the umbilical vessels.[36][38] Cytotrophoblast also forms a shell and anchoring villi that secure the chorion to the decidua basalis, enabling nutrient and gas exchange across the placental barrier.[36] The placenta forms gradually over the first three months, becoming fully functional by the fourth month, after which it grows in parallel with uterine expansion; by the fourth and fifth months, decidual septa divide it into 15-20 cotyledons.[37] At term, the discoid placenta measures 15-25 cm in diameter, 3 cm thick, and weighs 500-600 grams.[36] The umbilical cord develops concurrently, originating from the body stalk that connects the early embryo to the chorion, incorporating extraembryonic mesoderm and umbilical vessels as early as week 2.[39][37] By week 3, embryonic folding incorporates the vitelline duct (connecting to the yolk sac) and allantois (extending from the hindgut), refining the cord's structure as the amnion expands around the embryo in week 4.[39] It is fully formed by week 7, consisting of two umbilical arteries carrying deoxygenated fetal blood to the placenta and one umbilical vein returning oxygenated blood to the fetus, all embedded in protective mesenchymal tissue (Wharton's jelly).[39][37] This cord, typically 50-60 cm long at term, facilitates all fetoplacental blood exchange throughout gestation.[37]Fetal Development

Growth Patterns and Size Changes

The fetal stage begins at approximately 9 weeks after fertilization, equivalent to 11 weeks gestational age, and continues until birth, during which the fetus undergoes pronounced linear and volumetric growth.[7] Length, initially measured as crown-rump length, shifts to crown-heel length by around 14 weeks, increasing from about 7 cm to 50 cm by term, reflecting elongation of the trunk and limbs.[40] Weight escalates more dramatically from roughly 30 g to 3,400 g, with the most rapid gains occurring in the third trimester due to deposition of subcutaneous fat, organ enlargement, and skeletal mineralization.[40][41] Growth patterns exhibit distinct phases: moderate velocity in the second trimester, followed by acceleration in the third, where weekly weight increments can reach 200-250 g near term.[41] Ultrasound biometry tracks parameters like abdominal circumference, which shows an initial growth spurt peaking around 16 weeks before a secondary surge, correlating with nutritional demands via the placenta.[41] Head growth decelerates relative to body proportions, normalizing the cephalic index from embryonic dominance.[7] This fetal growth is reflected externally in maternal anatomy; by 22 weeks gestational age, the uterine fundus is approximately one inch above the belly button (navel), with the abdomen becoming prominently visible.[42]| Gestational Age (weeks) | Crown-Heel Length (cm) | Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 5.4 | 14 |

| 16 | 11.6 | 100 |

| 20 | 25.6 | 300 |

| 24 | 30.0 | 600 |

| 28 | 37.6 | 1,100 |

| 32 | 42.4 | 1,900 |

| 36 | 46.0 | 2,600 |

| 40 | 50.0 | 3,400 |

Maturation of Organ Systems

During the fetal period, which spans from the ninth week after fertilization to birth, organ systems transition from basic structural formation—completed largely during embryogenesis—to functional maturation essential for postnatal survival. This phase emphasizes growth, refinement of cellular and tissue architecture, and the onset of physiological activities, such as hormone production and waste excretion, driven by genetic programming and maternal-placental influences. Key developments include increasing organ vascularization, enzymatic activation, and preparatory adaptations like surfactant synthesis in the lungs.[44][45] The respiratory system's maturation occurs primarily through the canalicular stage (gestational weeks 16–26), when primitive acini form respiratory bronchioles, type I and II pneumocytes differentiate, and pulmonary capillaries proliferate for gas exchange potential. This progresses to the saccular stage (weeks 24–38), marked by thinning of inter-airspace septa, expansion of terminal sacs, and initial surfactant production by type II alveolar cells around week 24, which reduces surface tension to prevent alveolar collapse postnatally; surfactant levels rise significantly by weeks 32–36, correlating with viability in preterm births. Alveolarization, forming mature gas-exchange units, begins late in the third trimester and continues postnatally.[44][46] Cardiovascular maturation builds on the fully septated four-chambered heart established by week 8, with refinements in the conduction system—including sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes—enabling coordinated contractions at rates of 120–160 beats per minute by mid-gestation. Fetal circulation adapts via shunts (ductus arteriosus, foramen ovale, and ductus venosus) to bypass non-functional lungs, directing oxygenated blood from the placenta preferentially to the brain and heart; myocardial thickening and compliance improve progressively, supporting ejection fractions around 60–70% by term. Hepatic venous return and baroreceptor sensitivity also mature, preparing for circulatory transition at birth.[47][48] In the urinary system, the metanephric kidneys achieve functional maturity with nephrogenesis completing around gestational weeks 34–36, after which no new nephrons form. Glomerular filtration begins by week 10, producing urine that contributes to amniotic fluid volume from week 12 onward; tubular reabsorption matures with increasing sodium-potassium ATPase activity and renin-angiotensin system responsiveness by the third trimester, enabling fetal homeostasis of electrolytes and fluid balance. Bladder and ureteral peristalsis develop to prevent reflux, with full urodynamic capacity emerging near term.[49][50] Gastrointestinal maturation involves the liver's shift from hematopoiesis (dominant until week 10) to glycogen storage and bile synthesis by week 12, with hepatocytes maturing enzymatically for gluconeogenesis and detoxification by mid-gestation. The intestines elongate rapidly during weeks 9–10, rotating counterclockwise around the superior mesenteric artery; villi and microvilli form by week 12, enabling limited nutrient absorption primarily for fetal swallowing of amniotic fluid, while the pancreas develops exocrine and endocrine functions, including insulin secretion responsive to glucose by week 15. Meconium accumulation begins around week 16 from swallowed debris and biliary products.[51][52] The endocrine system's fetal components activate progressively, with the adrenal cortex producing cortisol from week 8, surging after week 30 under pituitary ACTH stimulation to induce lung maturation, hepatic enzyme induction, and gut barrier formation. The thyroid gland, functional by week 12, synthesizes thyroxine critical for brain development and metabolic rate; fetal pituitary hormones like growth hormone emerge by week 10, while pancreatic islets produce insulin from week 10–12, regulating fetal glucose uptake. These axes prepare for independent hormonal regulation postnatally, influenced by placental transfer of maternal hormones early on.[45][53]Sensory and Motor Development

During the fetal stage, sensory development progresses from rudimentary tactile sensitivity to functional responses across multiple modalities, enabling interaction with the intrauterine environment. Tactile sensation emerges earliest, with mechanoreceptors in the perioral region becoming responsive to stimulation around 7 weeks gestation, facilitating early self-touch behaviors such as hand-to-face contact by 10 weeks.[54] Touch receptors proliferate thereafter, appearing on the palms and soles by 12 weeks and extending to the trunk by 17 weeks, allowing the fetus to sense pressure from amniotic fluid and cord contact.[55] Proprioception and vestibular senses develop concurrently, with the inner ear's semicircular canals functional by 14-16 weeks, contributing to head and body orientation in utero.[54] Auditory maturation accelerates in the second trimester, as the cochlea achieves functionality around 20 weeks, permitting detection of low-frequency maternal sounds like heartbeat and voice, with initial responses to vibroacoustic stimuli evident by 19 weeks.[54] [56] Gustatory and olfactory systems integrate via amniotic fluid; taste buds form by 8-12 weeks, and swallowing begins around 12-14 weeks, exposing the fetus to flavors that influence postnatal preferences for sweetness.[57] Olfactory receptors develop later, with potential nasal breathing movements by 28 weeks allowing scent detection in fluid.[54] Visual development lags due to fused eyelids until 24-26 weeks and uterine opacity, though retinal layers mature by 20 weeks and fetal eye movements commence at 14-16 weeks; transabdominal light may elicit responses from 28 weeks onward.[54] Motor development parallels sensory maturation, initiating with spontaneous, jerky general body movements at 7-8 weeks, detectable via ultrasound as axial and limb twitches driven by spinal cord reflexes.[58] [54] By 9-10 weeks, movements diversify to include hiccups, breathing-like excursions, and isolated limb activity, transitioning to smoother, differentiated patterns by 20 weeks as cerebellar and cortical inputs integrate.[54] Specific motor behaviors emerge sequentially: grasping the umbilical cord at 12 weeks, thumb sucking by 13-15 weeks, and coordinated hand-mouth sequences by 16 weeks, reflecting sensorimotor feedback loops.[59] In the third trimester, movements increase in frequency and complexity, with periods of rest-activity cycling every 20-40 minutes, culminating in organized patterns like startle responses and preparatory reflexes for birth, such as the grasp and sucking instincts. Maternal perception of these ("quickening") typically occurs between 18-20 weeks, varying by parity and fetal position.[58] This progression underscores the fetus's capacity for self-generated activity, independent of external drive, fostering neuromuscular maturation essential for postnatal adaptation.[54]Neurological and Cognitive Foundations

Brain and Nervous System Formation

The formation of the brain and nervous system commences during the third week post-fertilization, with the induction of the neural plate from ectodermal cells along the dorsal midline of the embryo.[60] This process, known as neural induction, is triggered by signals from the underlying notochord and involves the differentiation of neural progenitor cells by the end of the third gestational week.[60] The neural plate thickens and folds, elevating neural folds that fuse to form the neural tube between days 20 and 27 post-conception, with the anterior neuropore closing around day 25 and the posterior neuropore by day 27.[61] Closure of the neural tube establishes the foundational structure of the central nervous system (CNS), comprising the brain anteriorly and spinal cord posteriorly; defects in this process, occurring before the end of the fourth week, result in neural tube defects such as anencephaly or spina bifida, affecting approximately 2 per 1,000 pregnancies.[61] By the end of the fourth week, the anterior neural tube segments into three primary brain vesicles: the prosencephalon (forebrain), mesencephalon (midbrain), and rhombencephalon (hindbrain).[62] These vesicles further differentiate during the fifth week, giving rise to five secondary vesicles by week 6: the telencephalon and diencephalon from the prosencephalon, mesencephalon remaining unchanged, and the metencephalon and myelencephalon from the rhombencephalon.[60] Concurrently, neural crest cells delaminate from the dorsal neural folds to contribute to the peripheral nervous system (PNS), forming sensory ganglia, autonomic ganglia, Schwann cells, and adrenal medulla chromaffin cells.[61] The spinal cord emerges from the caudal neural tube, with initial segmentation into neuromeres visible by week 4.[62] Neurogenesis, the production of neurons, initiates around week 6 in the ventricular zone of the neural tube, with proliferative neuroepithelial cells generating up to 15 million neurons per hour by weeks 12-14.[62] This phase establishes the basic neuronal population for the CNS, largely completing cortical neurogenesis by mid-gestation around week 15-20 post-conception.[60] Glial cells, including astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, begin differentiating later, supporting neuronal maturation and myelination, which starts in the fetal period but originates from these early formative events.[62] The intricate signaling pathways, such as Sonic hedgehog for ventral patterning and folate metabolism for tube closure, underscore the precision required, where disruptions can lead to profound neurological impairments.[61]Early Cognitive Capacities

Early cognitive capacities in the human fetus emerge primarily during the third trimester, manifesting as basic forms of learning such as habituation, classical conditioning, and exposure-based memory formation. Habituation, a process involving decreased responsiveness to repeated stimuli, provides evidence of attention, sensory discrimination, and short-term memory, with the earliest reliable observations occurring around 22-23 weeks of gestation in response to auditory tones.[63] By 30 weeks, fetuses demonstrate short-term memory retention over intervals of up to 10 minutes, as shown through habituation to vibroacoustic stimuli measured by fetal movement responses.[64] Classical conditioning, requiring association between a neutral stimulus and an unconditioned response, is evident from approximately 32 weeks gestation. In studies, fetuses exposed to a tone paired with vibroacoustic stimulation showed conditioned responses after 10-20 trials, with success rates around 50% in samples tested between 32 and 39 weeks.[63] This indicates the capacity for associative learning reliant on a functional central nervous system. Exposure learning further supports memory development, as fetuses between 30 and 37 weeks can form preferences for specific auditory patterns, such as musical themes, which persist into the neonatal period without further exposure.[63] Longer-term memory traces, spanning up to four weeks, are detectable by 34 weeks gestation. Fetuses habituated to stimuli at 34 weeks retain and retrieve this information when retested at 38 weeks, independent of ongoing exposure.[64][65] Auditory familiarity, particularly to the maternal voice, reinforces these capacities; third-trimester fetuses (from 34 weeks) exposed to maternal speech show enhanced neuronal coupling and autonomic responses to it in newborns, compared to unfamiliar voices.[66] These prenatal processes lay foundational neural pathways for postnatal cognition, though they represent rudimentary rather than complex higher-order functions.[63]Genetic and Biological Influences

Role of Genetics and Heredity

The zygote forms through the fusion of haploid gametes, inheriting 23 chromosomes from the maternal oocyte and 23 from the paternal sperm, resulting in a diploid set of 46 chromosomes that constitutes the complete genetic foundation for human development. This heritable genome comprises approximately 6 billion base pairs of DNA (3 billion from each parent), encoding roughly 20,000 protein-coding genes that dictate the sequence of cellular events from cleavage to organogenesis.[67][68] Variations in alleles inherited from parents introduce genetic diversity, influencing traits such as growth rates and susceptibility to developmental perturbations, while the equal contribution from both lineages ensures biparental inheritance as the causal basis for embryonic viability.[69] Gene expression patterns, governed by the inherited DNA sequence, orchestrate prenatal development through temporal and spatial regulation, where transcription factors activate specific loci to drive cell fate decisions and tissue specification. For instance, conserved gene regulatory networks, including those involving HOX cluster genes, establish the body axes and segmental identity during early embryogenesis, with disruptions leading to axial malformations observable in human congenital anomalies.[70][71] Hereditary factors manifest in polygenic influences on quantitative traits like fetal size, where genome-wide association studies indicate heritability estimates of 30-50% for birth weight, reflecting additive effects of numerous loci inherited from parents.[72] Chromosomal or single-gene mutations inherited via gametes can profoundly alter developmental trajectories, as seen in autosomal dominant disorders like achondroplasia (FGFR3 mutation, incidence ~1 in 25,000 births), which impairs endochondral ossification and results in disproportionate skeletal growth from early fetal stages. Aneuploidies such as trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), arising de novo or from parental meiotic errors in ~95% of cases, disrupt gene dosage and cause craniofacial dysmorphology and cardiac defects detectable prenatally. These hereditary disruptions underscore genetics as the primary determinant of developmental fidelity, with empirical data from prenatal genetic testing confirming causal links between specific variants and phenotypic outcomes.[73][74]Paternal Contributions

The paternal genome provides approximately 50% of the zygote's nuclear DNA at fertilization, influencing embryonic cleavage, implantation, and subsequent fetal growth through specific genetic contributions. Paternally derived genes, particularly those subject to genomic imprinting, promote placental and fetal resource acquisition, with disruptions leading to growth disorders such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome.[75][76] Sperm DNA integrity directly impacts early embryo development, as elevated fragmentation impairs cleavage rates and blastocyst formation, observable from day 2 post-fertilization. High sperm DNA damage correlates with chromosomal fragmentation in embryos, reducing implantation success and increasing miscarriage risk, even in intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles using high-quality oocytes.[77][78][79] Advanced paternal age, typically over 40 years, diminishes sperm quality via increased DNA fragmentation and de novo mutations, adversely affecting embryo aneuploidy rates and developmental competence. In vitro fertilization data indicate that paternal age beyond 45 reduces optimal embryo formation and live birth odds by 1-2.4% per additional year, particularly when combined with advanced maternal age. Animal models confirm these effects, showing reduced fetal weight and placental size in offspring of aged sires due to altered sperm epigenetics.[80][81][82] Paternal epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation and histone variants in sperm, transmit preconception environmental signals that regulate embryonic gene expression and trophoblast differentiation. For example, paternal high-fat diet exposure alters sperm small RNA profiles, leading to impaired glucose homeostasis and metabolic risks in offspring embryos. These intergenerational effects persist across multiple cell divisions, underscoring sperm's role beyond nuclear DNA in establishing developmental trajectories.[83][84][85]Epigenetic Mechanisms

Epigenetic mechanisms regulate gene expression during prenatal development without altering the underlying DNA sequence, primarily through DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs, enabling cellular differentiation and adaptation to environmental cues. These processes are essential for embryonic genome activation, X-chromosome inactivation, and genomic imprinting, where parent-specific gene expression patterns are established via differential methylation. For instance, global DNA demethylation occurs shortly after fertilization, followed by de novo methylation waves that stabilize cell fates by gestation week 8. Disruptions in these mechanisms can lead to developmental anomalies, as evidenced by studies linking aberrant methylation to congenital disorders like Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, characterized by overgrowth due to loss of imprinting at the IGF2/H19 locus.[86][87] DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of methyl groups to cytosine residues in CpG dinucleotides, typically repressing transcription by recruiting repressive chromatin complexes, and plays a pivotal role in silencing pluripotency genes during the transition from totipotent zygote to differentiated tissues. Histone modifications, such as acetylation on lysine residues promoting open chromatin (euchromatin) or methylation variants like H3K27me3 enforcing repression, dynamically orchestrate chromatin accessibility for lineage-specific gene activation in organogenesis. Non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs, further modulate these by targeting mRNAs for degradation or influencing chromatin remodeling, with evidence from human embryo studies showing their upregulation during gastrulation to fine-tune mesoderm formation. These mechanisms interact; for example, DNA methylation often correlates with histone deacetylation, reinforcing stable epigenetic states that persist postnatally.[88][87][89] Maternal factors influence fetal epigenetics, with nutrition providing substrates like folate and methionine for one-carbon metabolism that sustains methylation cycles, as demonstrated in cohort studies where maternal methionine supplementation altered offspring hepatic DNA methylation patterns detectable into infancy. Prenatal exposure to stressors or toxins can induce lasting epigenetic marks, such as hypomethylation at glucocorticoid receptor promoters linked to altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis programming, though human longitudinal data emphasize variability and the need for replication beyond associative findings. While animal models robustly show intergenerational transmission via sperm or oocyte epigenomes, human evidence remains correlative, underscoring the primacy of genetic stability over environmentally induced plasticity in core developmental trajectories.[90][91][92]Environmental and Maternal Influences

Nutrition and Metabolic Factors

Maternal nutrition profoundly influences fetal growth, organogenesis, and long-term health outcomes, with deficiencies or excesses altering placental function and nutrient transfer. Systematic reviews indicate that adherence to nutrient-dense dietary patterns, rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, during pregnancy reduces risks of preterm birth and low birth weight by optimizing fetal nutrient supply and mitigating oxidative stress.[93] Conversely, maternal undernutrition, characterized by inadequate caloric or micronutrient intake, restricts intrauterine growth, leading to fetal growth restriction (FGR) and increased neonatal morbidity, as evidenced by cohort studies linking early pregnancy caloric deficits to reduced placental blood flow and stunted fetal organ development.[94] [95] Specific micronutrients play causal roles in averting congenital anomalies. Folic acid supplementation at 400-800 μg daily from preconception through early pregnancy reduces neural tube defects (NTDs) by approximately 57%, a finding corroborated across meta-analyses of randomized trials, which attribute this to enhanced DNA synthesis and methylation preventing incomplete neural tube closure by week 4 post-conception.[96] [97] Iodine deficiency impairs maternal and fetal thyroid hormone production, essential for neuronal migration and myelination, resulting in cretinism and cognitive deficits in severe cases; supplementation trials show that maintaining urinary iodine above 150 μg/L during gestation preserves euthyroid states and supports brain development.[98] Iron deficiency anemia, prevalent in up to 40% of pregnancies in resource-limited settings, compromises oxygen delivery to the fetus, elevating risks of preterm delivery, low birth weight, and perinatal mortality by 20-30%, with longitudinal data confirming placental hypoxia as the mediating mechanism.[99] [100] Metabolic dysregulation exacerbates these risks through altered fetal programming. Maternal obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²) doubles stillbirth rates and promotes fetal macrosomia via hyperinsulinemia and adipokine dysregulation, with cohort studies documenting accelerated fetal abdominal growth and heightened offspring cardiometabolic risks persisting into adulthood.[101] [102] Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), diagnosed via impaired glucose tolerance, independently raises odds of cesarean delivery, neonatal hypoglycemia, and shoulder dystocia by 1.5-2-fold, as hyperglycaemia induces fetal pancreatic beta-cell hyperplasia and adiposity; intervention trials underscore tight glycemic control's role in mitigating these outcomes without fully eliminating long-term offspring obesity predisposition.[103] These factors interact causally with placental nutrient partitioning, where excess maternal lipids impair trophoblast invasion, underscoring the need for preconception metabolic optimization to foster resilient fetal development.[104]Substance Exposure and Teratogens