Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Human embryonic development

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Human growth and development |

|---|

|

| Stages |

| Biological milestones |

| Development and psychology |

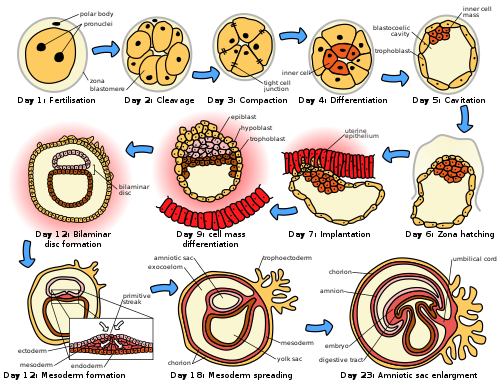

Human embryonic development or human embryogenesis is the development and formation of the human embryo. It is characterised by the processes of cell division and cellular differentiation of the embryo that occurs during the early stages of development. In biological terms, the development of the human body entails growth from a one-celled zygote to an adult human being. Fertilization occurs when the sperm cell successfully enters and fuses with an egg cell (ovum). The genetic material of the sperm and egg then combine to form the single cell zygote and the germinal stage of development commences. Human embryonic development covers the first eight weeks of development, which have 23 stages, called Carnegie stages. At the beginning of the ninth week, the embryo is termed a fetus (spelled "foetus" in British English). In comparison to the embryo, the fetus has more recognizable external features and a more complete set of developing organs.

Human embryology is the study of this development during the first eight weeks after fertilization. The normal period of gestation (pregnancy) is about nine months or 40 weeks.

The germinal stage refers to the time from fertilization through the development of the early embryo until implantation is completed in the uterus. The germinal stage takes around 10 days.[1] During this stage, the zygote divides in a process called cleavage. A blastocyst is then formed and implants in the uterus. Embryogenesis continues with the next stage of gastrulation, when the three germ layers of the embryo form in a process called histogenesis, and the processes of neurulation and organogenesis follow.

The entire process of embryogenesis involves coordinated spatial and temporal changes in gene expression, cell growth, and cellular differentiation. A nearly identical process occurs in other species, especially among chordates.

Germinal stage

[edit]Fertilization

[edit]Fertilization takes place when the spermatozoon has successfully entered the ovum and the two sets of genetic material carried by the gametes fuse together, resulting in the zygote (a single diploid cell). This usually takes place in the ampulla of one of the fallopian tubes. The zygote contains the combined genetic material carried by both the male and female gametes which consists of the 23 chromosomes from the nucleus of the ovum and the 23 chromosomes from the nucleus of the sperm. The 46 chromosomes undergo changes prior to the mitotic division which leads to the formation of the embryo having two cells.

Successful fertilization is enabled by three processes, which also act as controls to ensure species-specificity. The first is that of chemotaxis which directs the movement of the sperm towards the ovum.[2] Secondly, an adhesive compatibility between the sperm and the egg occurs. With the sperm adhered to the ovum, the third process of acrosomal reaction takes place; the front part of the spermatozoan head is capped by an acrosome which contains digestive enzymes to break down the zona pellucida and allow its entry.[3] The entry of the sperm causes calcium to be released which blocks entry to other sperm cells.[3] A parallel reaction takes place in the ovum called the zona reaction. This sees the release of cortical granules that release enzymes which digest sperm receptor proteins, thus preventing polyspermy.[4] The granules also fuse with the plasma membrane and modify the zona pellucida in such a way as to prevent further sperm entry.

Cleavage

[edit]

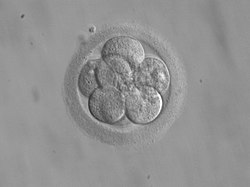

The beginning of the cleavage process is marked when the zygote divides through mitosis into two cells. This mitosis continues and the first two cells divide into four cells, then into eight cells and so on. Each division takes from 12 to 24 hours. The zygote is large compared to any other cell and undergoes cleavage without any overall increase in size. This means that with each successive subdivision, the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic material increases.[5]

Initially, the dividing cells, called blastomeres (blastos Greek for sprout), are undifferentiated and aggregated into a sphere enclosed within the zona pellucida of the ovum. When eight blastomeres have formed, they start to compact.[6] They begin to develop gap junctions, enabling them to develop in an integrated way and co-ordinate their response to physiological signals and environmental cues.[7]

When the cells number around sixteen, the solid sphere of cells within the zona pellucida is referred to as a morula.[8]

Blastulation

[edit]

Cleavage itself is the first stage in blastulation, the process of forming the blastocyst. Cells differentiate into an outer layer of cells called the trophoblast, and an inner cell mass. With further compaction the individual outer blastomeres, the trophoblasts, become indistinguishable. They are still enclosed within the zona pellucida. This compaction serves to make the structure watertight, containing the fluid that the cells will later secrete. The inner mass of cells differentiate to become embryoblasts and polarise at one end. They close together and form gap junctions, which facilitate cellular communication. This polarisation leaves a cavity, the blastocoel, creating a structure that is now termed the blastocyst. (In animals other than mammals, this is called the blastula).

The trophoblasts secrete fluid into the blastocoel. The resulting increase in size of the blastocyst causes it to hatch through the zona pellucida, which then disintegrates.[5] This process is called zona hatching and it takes place on the sixth day of embryo development, immediately before the implantation process. The hatching of the human embryo is supported by proteases secreted by the cells of the blastocyst, which digest proteins of the zona pellucida, giving rise to a hole. Then, due to the rhythmic expansion and contractions of the blastocyst, an increase of the pressure inside the blastocyst itself occurs, the hole expands and finally the blastocyst can emerge from this rigid envelope.

The inner cell mass will give rise to the pre-embryo,[9] the amnion, yolk sac and allantois, while the fetal part of the placenta will form from the outer trophoblast layer. The embryo plus its membranes is called the conceptus, and by this stage the conceptus has reached the uterus. The zona pellucida ultimately disappears completely, and the now exposed cells of the trophoblast allow the blastocyst to attach itself to the endometrium, where it will implant. The formation of the hypoblast and epiblast, which are the two main layers of the bilaminar germ disc, occurs at the beginning of the second week.[10] Both the embryoblast and the trophoblast will turn into two sub-layers.[11] The inner cells will turn into the hypoblast layer, which will surround the other layer, called the epiblast, and these layers will form the embryonic disc that will develop into the embryo.[10][11]

The trophoblast will also develop two sub-layers: the cytotrophoblast, which is in front of the syncytiotrophoblast, which in turn lies within the endometrium.[10] Next, another layer called the exocoelomic membrane or Heuser's membrane will appear and surround the cytotrophoblast, as well as the primitive yolk sac.[11] The syncytiotrophoblast will grow and will enter a phase called lacunar stage, in which some vacuoles will appear and be filled by blood in the following days.[10][11] The development of the yolk sac starts with the hypoblastic flat cells that form the exocoelomic membrane, which will coat the inner part of the cytotrophoblast to form the primitive yolk sac. An erosion of the endothelial lining of the maternal capillaries by the syncytiotrophoblastic cells results in the formation of the maternal sinusoids from where the blood will begin to penetrate and flow into and through the trophoblastic lacunae to give rise to the uteroplacental circulation.[12][13] Subsequently, new cells derived from yolk sac will be established between trophoblast and exocoelomic membrane and will give rise to extra-embryonic mesoderm, which will form the chorionic cavity.[11]

At the end of the second week of development, some cells of the trophoblast penetrate and form rounded columns into the syncytiotrophoblast. These columns are known as primary villi. At the same time, other migrating cells form into the exocoelomic cavity a new cavity named the secondary or definitive yolk sac, smaller than the primitive yolk sac.[11][12]

Implantation

[edit]

After ovulation, the endometrial lining becomes transformed into a secretory lining in preparation of accepting the embryo. It becomes thickened, with its secretory glands becoming elongated, and is increasingly vascular. This lining of the uterine cavity (or womb) is now known as the decidua, and it produces a great number of large decidual cells in its increased interglandular tissue. The blastomeres in the blastocyst are arranged into an outer layer called the trophoblast. The trophoblast then differentiates into an inner layer, the cytotrophoblast, and an outer layer, the syncytiotrophoblast. The cytotrophoblast contains cuboidal epithelial cells and is the source of dividing cells, and the syncytiotrophoblast is a syncytial layer without cell boundaries.

The syncytiotrophoblast implants the blastocyst in the decidual epithelium by projections of chorionic villi, forming the embryonic part of the placenta. The placenta develops once the blastocyst is implanted, connecting the embryo to the uterine wall. The decidua here is termed the decidua basalis; it lies between the blastocyst and the myometrium and forms the maternal part of the placenta. The implantation is assisted by hydrolytic enzymes that erode the epithelium. The syncytiotrophoblast also produces human chorionic gonadotropin, a hormone that stimulates the release of progesterone from the corpus luteum. Progesterone enriches the uterus with a thick lining of blood vessels and capillaries so that it can oxygenate and sustain the developing embryo. The uterus liberates sugar from stored glycogen from its cells to nourish the embryo.[14] The villi begin to branch and contain blood vessels of the embryo. Other villi, called terminal or free villi, exchange nutrients. The embryo is joined to the trophoblastic shell by a narrow connecting stalk that develops into the umbilical cord to attach the placenta to the embryo.[11][15] Arteries in the decidua are remodelled to increase the maternal blood flow into the intervillous spaces of the placenta, allowing gas exchange and the transfer of nutrients to the embryo. Waste products from the embryo will diffuse across the placenta.

As the syncytiotrophoblast starts to penetrate the uterine wall, the inner cell mass (embryoblast) also develops. The inner cell mass is the source of embryonic stem cells, which are pluripotent and can develop into any one of the three germ layer cells, and which have the potency to give rise to all the tissues and organs.

Embryonic disc

[edit]The embryoblast forms an embryonic disc of two layers, the upper layer is called the epiblast and the lower layer, the hypoblast. The disc is stretched between what will become the amniotic cavity and the yolk sac. The epiblast is adjacent to the trophoblast and made of columnar cells; the hypoblast is closest to the blastocyst cavity and made of cuboidal cells. The epiblast migrates away from the trophoblast downwards, forming the amniotic cavity, the lining of which is formed from amnioblasts developed from the epiblast. The hypoblast is pushed down and forms the yolk sac (exocoelomic cavity) lining. Some hypoblast cells migrate along the inner cytotrophoblast lining of the blastocoel, secreting an extracellular matrix along the way. These hypoblast cells and extracellular matrix are called Heuser's membrane (or the exocoelomic membrane), and they cover the blastocoel to form the yolk sac (or exocoelomic cavity). Cells of the hypoblast migrate along the outer edges of this reticulum and form the extraembryonic mesoderm; this disrupts the extraembryonic reticulum. Soon pockets form in the reticulum, which ultimately coalesce to form the chorionic cavity (extraembryonic coelom).

Gastrulation

[edit]

The primitive streak, a linear collection of cells formed by the migrating epiblast, appears, and this marks the beginning of gastrulation, which takes place around the seventeenth day (week 3) after fertilization. The process of gastrulation reorganises the two-layer embryo into a three-layer embryo, and also gives the embryo its specific head-to-tail, and front-to-back orientation, by way of the primitive streak which establishes bilateral symmetry. A primitive node (or primitive knot) forms in front of the primitive streak which is the organiser of neurulation. A primitive pit forms as a depression in the centre of the primitive node which connects to the notochord which lies directly underneath. The node has arisen from epiblasts of the amniotic cavity floor, and it is this node that induces the formation of the neural plate which serves as the basis for the nervous system.

The neural plate will form opposite the primitive streak from ectodermal tissue which thickens and flattens into the neural plate. The epiblast in that region moves down into the streak at the location of the primitive pit where the process called ingression, which leads to the formation of the mesoderm takes place. This ingression sees the cells from the epiblast move into the primitive streak in an epithelial-mesenchymal transition; epithelial cells become mesenchymal stem cells, multipotent stromal cells that can differentiate into various cell types. The hypoblast is pushed out of the way and goes on to form the amnion. The epiblast keeps moving and forms a second layer, the mesoderm. The epiblast has now differentiated into the three germ layers of the embryo, so that the bilaminar disc is now a trilaminar disc, the gastrula.

The three germ layers are the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm, and are formed as three overlapping flat discs. It is from these three layers that all the structures and organs of the body will be derived through the processes of somitogenesis, histogenesis and organogenesis.[16] The embryonic endoderm is formed by invagination of epiblastic cells that migrate to the hypoblast, while the mesoderm is formed by the cells that develop between the epiblast and endoderm. In general, all germ layers will derive from the epiblast.[11][15] The upper layer of ectoderm will give rise to the outermost layer of skin, central and peripheral nervous systems, eyes, inner ear, and many connective tissues.[17] The middle layer of mesoderm will give rise to the heart and the beginning of the circulatory system as well as the bones, muscles and kidneys. The inner layer of endoderm will serve as the starting point for the development of the lungs, intestine, thyroid, pancreas and bladder.

Following ingression, a blastopore develops where the cells have ingressed, in one side of the embryo and it deepens to become the archenteron, the first formative stage of the gut. As in all deuterostomes, the blastopore becomes the anus whilst the gut tunnels through the embryo to the other side where the opening becomes the mouth. With a functioning digestive tube, gastrulation is now completed and the next stage of neurulation can begin.

Neurulation

[edit]

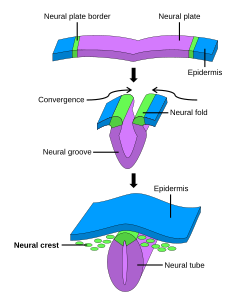

Following gastrulation, the ectoderm gives rise to epithelial and neural tissue, and the gastrula is now referred to as the neurula. The neural plate that has formed as a thickened plate from the ectoderm, continues to broaden and its ends start to fold upwards as neural folds. Neurulation refers to this folding process whereby the neural plate is transformed into the neural tube, and this takes place during the fourth week. They fold, along a shallow neural groove which has formed as a dividing median line in the neural plate. This deepens as the folds continue to gain height, when they will meet and close together at the neural crest. The cells that migrate through the most cranial part of the primitive line form the paraxial mesoderm, which will give rise to the somitomeres that in the process of somitogenesis will differentiate into somites that will form the sclerotomes, the syndetomes,[18] the myotomes and the dermatomes to form cartilage and bone, tendons, dermis (skin), and muscle. The intermediate mesoderm gives rise to the urogenital tract and consists of cells that migrate from the middle region of the primitive line. Other cells migrate through the caudal part of the primitive line and form the lateral mesoderm, and those cells migrating by the most caudal part contribute to the extraembryonic mesoderm.[11][15]

The embryonic disc begins flat and round, but eventually elongates to have a wider cephalic part and narrow-shaped caudal end.[10] At the beginning, the primitive line extends in cephalic direction and 18 days after fertilization returns caudally until it disappears. In the cephalic portion, the germ layer shows specific differentiation at the beginning of the fourth week, while in the caudal portion it occurs at the end of the fourth week.[11] Cranial and caudal neuropores become progressively smaller until they close completely (by day 26) forming the neural tube.[19]

Development of organs and organ systems

[edit]

Organogenesis is the development of the organs that begins during the third to eighth week, and continues until birth. Sometimes full development, as in the lungs, continues after birth. Different organs take part in the development of the many organ systems of the body.

Blood

[edit]Haematopoietic stem cells that give rise to all the blood cells develop from the mesoderm. The development of blood formation takes place in clusters of blood cells, known as blood islands, in the yolk sac. Blood islands develop outside the embryo, on the umbilical vesicle, allantois, connecting stalk, and chorion, from mesodermal hemangioblasts.

In the centre of a blood island, hemangioblasts form the haematopoietic stem cells that are the precursor to all types of blood cell. In the periphery of a blood island the hemangioblasts differentiate into angioblasts, the precursors to the blood vessels.[20]

Heart and circulatory system

[edit]

The heart is the first functional organ to develop and starts to beat and pump blood at around 22 days.[21] Cardiac myoblasts and blood islands in the splanchnopleuric mesenchyme on each side of the neural plate give rise to the cardiogenic region.[11]: 165 This is a horseshoe-shaped area near to the head of the embryo. By day 19, following cell signalling, two strands begin to form as tubes in this region, as a lumen develops within them. These two endocardial tubes grow and by day 21 have migrated towards each other and fused to form a single primitive heart tube, the tubular heart. This is enabled by the folding of the embryo which pushes the tubes into the thoracic cavity.[22]

Also at the same time that the endocardial tubes are forming, vasculogenesis (the development of the circulatory system) has begun. This starts on day 18 with cells in the splanchnopleuric mesoderm differentiating into angioblasts that develop into flattened endothelial cells. These join to form small vesicles called angiocysts which join up to form long vessels called angioblastic cords. These cords develop into a pervasive network of plexuses in the formation of the vascular network. This network grows by the additional budding and sprouting of new vessels in the process of angiogenesis.[22] Following vasculogenesis and the development of an early vasculature, a stage of vascular remodelling takes place.

The tubular heart quickly forms five distinct regions. From head to tail, these are the infundibulum, bulbus cordis, primitive ventricle, primitive atrium, and the sinus venosus. Initially, all venous blood flows into the sinus venosus, and is propelled from tail to head to the truncus arteriosus. This will divide to form the aorta and pulmonary artery; the bulbus cordis will develop into the right (primitive) ventricle; the primitive ventricle will form the left ventricle; the primitive atrium will become the front parts of the left and right atria and their appendages, and the sinus venosus will develop into the posterior part of the right atrium, the sinoatrial node and the coronary sinus.[21]

Cardiac looping begins to shape the heart as one of the processes of morphogenesis, and this completes by the end of the fourth week. Programmed cell death (apoptosis) at the joining surfaces enables fusion to take place.[22] In the middle of the fourth week, the sinus venosus receives blood from the three major veins: the vitelline, the umbilical and the common cardinal veins.

During the first two months of development, the interatrial septum begins to form. This septum divides the primitive atrium into a right and a left atrium. Firstly it starts as a crescent-shaped piece of tissue which grows downwards as the septum primum. The crescent shape prevents the complete closure of the atria allowing blood to be shunted from the right to the left atrium through the opening known as the ostium primum. This closes with further development of the system but before it does, a second opening (the ostium secundum) begins to form in the upper atrium enabling the continued shunting of blood.[22]

A second septum (the septum secundum) begins to form to the right of the septum primum. This also leaves a small opening, the foramen ovale which is continuous with the previous opening of the ostium secundum. The septum primum is reduced to a small flap that acts as the valve of the foramen ovale and this remains until its closure at birth. Between the ventricles the septum inferius also forms which develops into the muscular interventricular septum.[22]

Digestive system

[edit]The digestive system starts to develop from the third week and by the twelfth week, the organs have correctly positioned themselves.

Respiratory system

[edit]The respiratory system develops from the lung bud, which appears in the ventral wall of the foregut about four weeks into development. The lung bud forms the trachea and two lateral growths known as the bronchial buds, which enlarge at the beginning of the fifth week to form the left and right main bronchi. These bronchi in turn form secondary (lobar) bronchi; three on the right and two on the left (reflecting the number of lung lobes). Tertiary bronchi form from secondary bronchi.

While the internal lining of the larynx originates from the lung bud, its cartilages and muscles originate from the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arches.[23]

Urinary system

[edit]Kidneys

[edit]Three different kidney systems form in the developing embryo: the pronephros, the mesonephros and the metanephros. Only the metanephros develops into the permanent kidney. All three are derived from the intermediate mesoderm.

Pronephros

[edit]The pronephros derives from the intermediate mesoderm in the cervical region. It is not functional and degenerates before the end of the fourth week.

Mesonephros

[edit]The mesonephros derives from intermediate mesoderm in the upper thoracic to upper lumbar segments. Excretory tubules are formed and enter the mesonephric duct, which ends in the cloaca. The mesonephric duct atrophies in females, but participate in development of the reproductive system in males.

Metanephros

[edit]The metanephros appears in the fifth week of development. An outgrowth of the mesonephric duct, the ureteric bud, penetrates metanephric tissue to form the primitive renal pelvis, renal calyces and renal pyramids. The ureter is also formed.

Bladder and urethra

[edit]Between the fourth and seventh weeks of development, the urorectal septum divides the cloaca into the urogenital sinus and the anal canal. The upper part of the urogenital sinus forms the bladder, while the lower part forms the urethra.[23]

Reproductive system

[edit]Integumentary system

[edit]The superficial layer of the skin, the epidermis, is derived from the ectoderm. The deeper layer, the dermis, is derived from mesenchyme.

The formation of the epidermis begins in the second month of development and it acquires its definitive arrangement at the end of the fourth month. The ectoderm divides to form a flat layer of cells on the surface known as the periderm. Further division forms the individual layers of the epidermis.

The mesenchyme that will form the dermis is derived from three sources:

- The mesenchyme that forms the dermis in the limbs and body wall derives from the lateral plate mesoderm

- The mesenchyme that forms the dermis in the back derives from paraxial mesoderm

- The mesenchyme that forms the dermis in the face and neck derives from neural crest cells[23]

Nervous system

[edit]

Late in the fourth week, the superior part of the neural tube bends ventrally as the cephalic flexure at the level of the future midbrain—the mesencephalon.[24] Above the mesencephalon is the prosencephalon (future forebrain) and beneath it is the rhombencephalon (future hindbrain).

Cranial neural crest cells migrate to the pharyngeal arches as neural stem cells, where they develop in the process of neurogenesis into neurons.

The optical vesicle (which eventually becomes the optic nerve, retina and iris) forms at the basal plate of the prosencephalon. The alar plate of the prosencephalon expands to form the cerebral hemispheres (the telencephalon) whilst its basal plate becomes the diencephalon. Finally, the optic vesicle grows to form an optic outgrowth.

Development of physical features

[edit]

Face and neck

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2017) |

From the third to the eighth week the face and neck develop.

Ears

[edit]The inner ear, middle ear and outer ear have distinct embryological origins.

Inner ear

[edit]At about 22 days into development, the ectoderm on each side of the rhombencephalon thickens to form otic placodes. These placodes invaginate to form otic pits, and then otic vesicles. The otic vesicles then form ventral and dorsal components.

The ventral component forms the saccule and the cochlear duct. In the sixth week of development the cochlear duct emerges and penetrates the surrounding mesenchyme, travelling in a spiral shape until it forms 2.5 turns by the end of the eighth week. The saccule is the remaining part of the ventral component. It remains connected to the cochlear duct via the narrow ductus reuniens.

The dorsal component forms the utricle and semicircular canals.

Middle ear

[edit]The first pharyngeal pouch lengthens and expands to form the tubotympanic recess. This recess differentiates to form most of the tympanic cavity of the middle ear, and all of the Eustachian or auditory tube. The narrow auditory tube connects the tympanic cavity to the pharynx.[25]

The bones of the middle ear, the ossicles, derive from the cartilages of the pharyngeal arches. The malleus and incus derive from the cartilage of the first pharyngeal arch, whereas the stapes derives from the cartilage of the second pharyngeal arch.

Outer ear

[edit]The external auditory meatus develops from the dorsal portion of the first pharyngeal cleft. Six auricular hillocks, which are mesenchymal proliferations at the dorsal aspects of the first and second pharyngeal arches, form the auricle of the ear.[23]

Eyes

[edit]The eyes begin to develop from the third week to the tenth week.

Limbs

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2017) |

At the end of the fourth week limb development begins. Limb buds appear on the ventrolateral aspect of the body. They consist of an outer layer of ectoderm and an inner part consisting of mesenchyme which is derived from the parietal layer of lateral plate mesoderm. Ectodermal cells at the distal end of the buds form the apical ectodermal ridge, which creates an area of rapidly proliferating mesenchymal cells known as the progress zone. Cartilage (some of which ultimately becomes bone) and muscle develop from the mesenchyme.[23]

Clinical significance

[edit]Toxic exposures in the embryonic period can be the cause of major congenital malformations, since the precursors of the major organ systems are now developing.

Each cell of the preimplantation embryo has the potential to form all of the different cell types in the developing embryo. This cell potency means that some cells can be removed from the preimplantation embryo and the remaining cells will compensate for their absence. This has allowed the development of a technique known as preimplantation genetic diagnosis, whereby a small number of cells from the preimplantation embryo created by IVF, can be removed by biopsy and subjected to genetic diagnosis. This allows embryos that are not affected by defined genetic diseases to be selected and then transferred to the pregnant woman's uterus.

Sacrococcygeal teratomas, tumours formed from different types of tissue, that can form, are thought to be related to primitive streak remnants, which ordinarily disappear.[10][11][13]

First arch syndromes are congenital disorders of facial deformities, caused by the failure of neural crest cells to migrate to the first pharyngeal arch.

Spina bifida a congenital disorder is the result of the incomplete closure of the neural tube.

Vertically transmitted infections can be passed from the pregnant woman to the unborn child at any stage of its development.

Hypoxia a condition of inadequate oxygen supply can be a serious consequence of a preterm or premature birth.

See also

[edit]Additional images

[edit]-

Representing different stages of embryogenesis

-

Early stage of the gastrulation process

-

Phase of the gastrulation process

-

Top of the form of the embryo

-

Establishment of embryo medium

-

Spinal cord at five weeks

-

Head and neck at 32 days

References

[edit]- ^ "germinal stage". Mosby's Medical Dictionary, 8th edition. Elsevier. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ Marlow, Florence L (2020). Maternal Effect Genes in Development. Academic Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0128152218.

- ^ a b Singh, Vishram (2013). Textbook of Clinical Embryology – E-book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 35. ISBN 978-8131236208.

- ^ Standring, Susan (2015). Gray's Anatomy E-Book: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 163. ISBN 978-0702068515.

- ^ a b Forgács, G.; Newman, Stuart A. (2005). "Cleavage and blastula formation". Biological physics of the developing embryo. Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-521-78337-8.

- ^ Standring, Susan (2015). Gray's Anatomy E-Book: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 166. ISBN 978-0702068515.

- ^ Brison, D. R.; Sturmey, R. G.; Leese, H. J. (2014). "Metabolic heterogeneity during preimplantation development: the missing link?". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (5): 632–640. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu018. ISSN 1355-4786. PMID 24795173.

- ^ Boklage, Charles E. (2009). How New Humans Are Made: Cells and Embryos, Twins and Chimeras, Left and Right, Mind/Self/Soul, Sex, and Schizophrenia. World Scientific. p. 217. ISBN 978-981-283-513-0.

- ^ "28.2 Embryonic Development – Anatomy and Physiology". opentextbc.ca.

- ^ a b c d e f Carlson, Bruce M. (1999) [1t. Pub. 1997]. "Chapter 4: Formation of germ layers and initial derivatives". Human Embryology & Developmental Biology. Mosby, Inc. pp. 62–68. ISBN 0-8151-1458-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Sadler, T.W.; Langman, Jan (2012) [1st. Pub. 2001]. "Chapter 3: Primera semana del desarrollo: de la ovulación a la implantación". In Seigafuse, sonya (ed.). Langman, Embriología médica. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Wolters Kluwer. pp. 29–42. ISBN 978-84-15419-83-9.

- ^ a b Moore, Keith L.; Persaud, V.N. (2003) [1t. Pub. 1996]. "Chapter 3: Formation of the bilaminar embryonic disc: second week". The Developing Human, Clinically Oriented Embryology. W B Saunders Co. pp. 47–51. ISBN 0-7216-9412-8.

- ^ a b Larsen, William J.; Sherman, Lawrence S.; Potter, S. Steven; Scott, William J. (2001) [1t. Pub. 1998]. "Chapter 2: Bilaminar embryonic disc development and establishment of the uteroplacental circulation". Human Embryology. Churchill Livingstone. pp. 37–45. ISBN 0-443-06583-7.

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Brad Williamson; Robin J. Heyden (2006). Biology: Exploring Life. Boston: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-250882-6.

- ^ a b c Smith Agreda, Víctor; Ferrés Torres, Elvira; Montesinos Castro-Girona, Manuel (1992). "Chapter 5: Organización del desarrollo: Fase de germinación". Manual de embriología y anatomía general. Universitat de València. pp. 72–85. ISBN 84-370-1006-3.

- ^ Schünke, Michael; Ross, Lawrence M.; Schulte, Erik; Schumacher, Udo; Lamperti, Edward D. (2006). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. ISBN 978-3-13-142081-7.

- ^ "Pregnancy week by week". Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Brent AE, Schweitzer R, Tabin CJ (April 2003). "A somitic compartment of tendon progenitors". Cell. 113 (2): 235–48. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00268-X. PMID 12705871. S2CID 16291509.

- ^ Larsen, W J (2001). Human Embryology (3rd ed.). Elsevier. p. 87. ISBN 0-443-06583-7.

- ^ Sadler, T.W. (2010). Langman's Medical Embryology (11th ed.). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams &Wilkins. pp. 79–81. ISBN 9780781790697.

- ^ a b Betts, J. Gordon (2013). Anatomy & physiology. pp. 787–846. ISBN 978-1938168130.

- ^ a b c d e Larsen, W J (2001). Human Embryology (3rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 170–190. ISBN 0-443-06583-7.

- ^ a b c d e Sadler, Thomas W. (2012). Langman's medical embryology. Langman, Jan. (12th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781451113426. OCLC 732776409.

- ^ Zhou, Yi; Song, Hongjun; Ming, Guo-Li (2023-07-28). "Genetics of human brain development". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 25: 26–45. doi:10.1038/s41576-023-00626-5. ISSN 1471-0064. PMC 10926850. PMID 37507490.

- ^ Larsen's human embryology (5. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone. 2015. p. 485. ISBN 9781455706846.

External links

[edit]Human embryonic development

View on GrokipediaTerminology and Scope

Definition and Biological Criteria

Human embryonic development encompasses the progression from the fertilization of a human oocyte by a sperm, resulting in a zygote with a unique diploid genome, through rapid cellular divisions, differentiation, and the establishment of the foundational body plan up to the eighth week post-fertilization. This phase is characterized by the transition from a totipotent single cell capable of forming both embryonic and extraembryonic tissues to a multicellular structure with three primary germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm), marking the onset of organogenesis.[1][11] Biologically, it concludes when the embryo exhibits recognizable external features and internal organ rudiments, distinguishing it from subsequent fetal development focused on growth and refinement.[6] The biological criteria for identifying the embryonic stage emphasize empirical markers of organized development rather than arbitrary gestational thresholds. At fertilization, completion occurs with the fusion of pronuclei and the first mitotic division, establishing a discrete entity with inherent potential for self-directed maturation into a mature organism, independent of mode of origin such as somatic cell nuclear transfer.[12] Key criteria include cellular totipotency in early blastomeres, which persists until the 4- to 8-cell stage, followed by compaction into a morula and cavitation to form a blastocyst with a pluripotent inner cell mass destined for the embryo proper.[3] Post-implantation, criteria shift to morphological and histological features, such as the presence of an embryonic disc, bilaminar structure (epiblast and hypoblast), and gastrulation initiating trilaminar organization, verifiable via Carnegie staging system stages 5 through 23, based on somite counts, limb bud formation, and neural tube closure.[13][6] These criteria underscore causal continuity from zygotic genome activation—evident by the 4- to 8-cell transition in humans—to coordinated tissue specification, excluding entities lacking such developmental trajectory, like isolated stem cell aggregates without intrinsic implantation potential.[3] Peer-reviewed embryological analyses prioritize these observable, reproducible traits over legal or ethical overlays, affirming the embryo as a distinct human organism from syngamy onward.[11][1]Timeline and Distinction from Fetal Period

Human embryonic development spans from fertilization to the completion of the eighth week post-fertilization, encompassing approximately 56 days during which the foundational body plan and major organ systems form through organogenesis.[8] This period aligns with Carnegie stages 1 through 23, a standardized system based on observable external and internal morphological criteria rather than exact chronological time, accounting for natural variability in growth rates.[8] In terms of gestational age, calculated from the first day of the last menstrual period, the embryonic phase corresponds roughly to weeks 3 through 10, though fertilization typically occurs around gestational week 2.[5] The distinction from the fetal period, which commences at week 9 post-fertilization and extends to birth, lies primarily in developmental priorities and morphological characteristics. During the embryonic stage, the conceptus transitions from a zygote to a recognizable human form with nascent organ primordia, emphasizing histogenesis and organ differentiation amid rapid cellular proliferation; this renders it particularly vulnerable to teratogenic insults that can cause congenital malformations.[5][14] In contrast, the fetal period focuses on somatic growth, refinement of organ functionality, and deposition of adipose tissue, with reduced risk of structural defects but increased emphasis on quantitative expansion and physiological maturation.[5] This demarcation is not arbitrary but rooted in empirical observations of developmental milestones, such as the completion of major organogenesis by week 8, after which proportional changes dominate.[8] The precise endpoint of the embryonic period is defined by the attainment of a crown-rump length of about 30 mm and the presence of distinct facial features, limbs, and external genitalia precursors, marking the shift where further development builds upon rather than establishes the basic architecture.[5] Peer-reviewed embryology references consistently uphold this timeline, drawing from histological and ultrasonographic data across cohorts, underscoring the causal progression from cellular specification to integrated organ systems.[14][5]Fertilization and Preimplantation Development

Fertilization Mechanisms

Human fertilization typically occurs in the ampulla of the uterine tube, where a single spermatozoon fuses with a secondary oocyte arrested in metaphase of the second meiotic division.[15] This process begins with the spermatozoon's capacitation in the female reproductive tract, involving removal of cholesterol from the plasma membrane, increased membrane fluidity, and hyperactivated motility to facilitate progression through the cumulus oophorus cells surrounding the oocyte.[16] Capacitation primes the sperm for the acrosome reaction but does not trigger it; instead, it enables species-specific binding to the zona pellucida (ZP), a glycoprotein matrix secreted by the oocyte.[17] Upon binding to ZP glycoproteins, particularly ZP3 in humans, the sperm undergoes the acrosome reaction, wherein the acrosomal vesicle fuses with the plasma membrane, exposing hydrolytic enzymes such as acrosin that digest the ZP matrix for penetration.[16] Acrosin, a serine protease, is essential for this enzymatic digestion, as evidenced by studies showing impaired ZP traversal in acrosin-deficient models, though human-specific redundancy may exist.[18] Multiple acrosome-intact sperm initially bind the ZP, but only those undergoing the reaction proceed; penetration relies on thrusting motility aided by dynein-powered flagellar beating.[19] This step ensures monospermy by limiting access, with the inner acrosomal membrane then interacting with the oocyte's plasma membrane (oolemma).[16] Sperm-oolemma fusion initiates at the equatorial segment of the sperm head, mediated by fusogenic proteins including IZUMO1 on the sperm and JUNO (folate receptor 4) on the oocyte, which form a heteromeric complex essential for membrane merger.[20] Fusion delivers the sperm's haploid genome into the ooplasm, triggering oocyte activation via oscillations in intracellular calcium concentration, which completes meiosis II and forms the second polar body.[21] Concurrently, the cortical reaction releases enzymes from cortical granules that modify the ZP—hardening it via cross-linking and stripping sperm receptors—to prevent polyspermy.[16] The sperm nucleus decondenses, and male and female pronuclei form, migrating to fuse and restore diploidy, marking syngamy and zygote formation within approximately 24 hours.[15]Cleavage and Morula Stage

Cleavage begins shortly after fertilization as the zygote, a single diploid cell, undergoes successive mitotic divisions to produce blastomeres, smaller daughter cells that collectively maintain the original cytoplasmic volume without net growth. These divisions are powered initially by maternal mRNAs and proteins stored in the oocyte, with embryonic genome activation occurring around the 4- to 8-cell stage. Blastomeres remain totipotent during early cleavages, capable of developing into complete organisms if isolated. The process unfolds in the ampulla of the fallopian tube as the embryo is transported toward the uterus.[1][22] The first cleavage division, typically meridional along the animal-vegetal axis, yields the 2-cell stage approximately 24 to 36 hours post-fertilization. Subsequent cleavages produce the 4-cell stage by about 40 to 56 hours, often with the second division being equatorial or meridional, influencing embryo geometry and developmental competence. By 72 hours, the 8-cell stage is reached, marked by initial radial polarization of blastomeres involving apical and basolateral domains regulated by Par proteins and the cytoskeleton. Divisions remain largely synchronous in viable embryos, though variability correlates with aneuploidy risk.[23][22][1] Transitioning to the morula stage occurs around days 3 to 4 post-fertilization, forming a compact sphere of 16 to 32 blastomeres resembling a mulberry. Compaction initiates primarily at or after the 8-cell stage, driven by increased E-cadherin-mediated adhesion, cell flattening, and tight junction formation, which obscure cell boundaries and establish cell polarity. This process sorts cells into outer positions fated toward trophectoderm via Hippo signaling suppression and inner positions toward the inner cell mass via pathway activation. Compaction serves as a critical checkpoint for embryo viability, with timely and complete compaction predicting higher blastocyst formation rates. The morula remains enclosed by the zona pellucida, preventing premature implantation.[1][24][22]Blastocyst Formation and Hatching

The blastocyst stage in human embryonic development follows the morula phase, occurring approximately 5 to 6 days after fertilization, when the embryo consists of 50 to 150 cells and develops a fluid-filled cavity known as the blastocoel.[1] This transformation begins with compaction of the morula, where outer cells polarize and form tight junctions, enabling selective ion transport that drives fluid accumulation into the intercellular spaces, leading to cavitation and blastocyst formation.[25] The resulting structure features an outer layer of trophectoderm cells, which will contribute to placental tissues, surrounding the inner cell mass (also called embryoblast), destined to form the fetus proper.[1] By day 5 post-fertilization, the early blastocyst emerges, with the trophectoderm secreting fluid via Na+/K+-ATPase pumps to expand the blastocoel, increasing embryonic volume up to 30-fold.[25] Expansion continues through day 6, as the blastocyst reaches its fully expanded state, preparing for hatching from the zona pellucida, the glycoprotein shell inherited from the oocyte that previously protected the embryo during cleavage.[1] This stage is critical, as metabolic demands shift toward glycolysis in the trophectoderm to support rapid expansion, while the inner cell mass remains relatively quiescent.[25] Hatching involves the blastocyst actively escaping the zona pellucida, typically occurring around day 6 to 7 post-fertilization, through a combination of mechanical forces and enzymatic activity.[26] The expanded blastocyst exerts hydrostatic pressure on the zona, causing localized thinning and rupture, often at the pole opposite the inner cell mass, followed by trophectoderm cells pushing through the breach via contractions and active motility.[27]61757-9/pdf) Studies indicate that mechanical stretching of the zona by the growing blastocyst is essential for efficient hatching, with failure in this process—due to zona thickening from advanced maternal age or cryopreservation artifacts—correlating with reduced implantation rates in assisted reproduction.[28][29] Successful hatching allows direct contact with the uterine endometrium, initiating implantation, and underscores the embryo's autonomous capacity for self-propelled emergence without maternal enzymatic aid.[26]Implantation Process

The implantation process in human embryonic development begins approximately 6 to 10 days after fertilization, coinciding with days 20 to 24 of a typical 28-day menstrual cycle, when the hatched blastocyst contacts the uterine endometrium.[30] This event requires synchrony between embryonic competence and maternal receptivity, occurring within a narrow "window of implantation" that opens around 6 days post-luteinizing hormone surge and lasts about 4 days.[31] Prior to implantation, the blastocyst must hatch from the zona pellucida, allowing direct trophectoderm-endometrium interaction; failure in hatching or timing disrupts attachment.[32] The process unfolds in three sequential phases: apposition, adhesion, and invasion. Apposition involves initial, reversible contact between the polar trophectoderm of the blastocyst and the endometrial luminal epithelium, often with the embryonic pole oriented toward the uterine surface.[30] Adhesion follows, strengthening via upregulated adhesion molecules such as integrins and selectins on trophoblast cells binding to endometrial receptors, facilitated by endometrial pinopodes—progesterone-induced protrusions that enhance surface interaction.[32] Maternal decidualization, driven by progesterone, preconditions the endometrium by transforming stromal cells into secretory decidual cells and recruiting uterine natural killer cells to modulate inflammation and vascular permeability.[31] Invasion marks the invasive phase, unique to humans as interstitial embedding where the entire conceptus buries within the endometrium up to the inner myometrium. Trophectoderm differentiates into syncytiotrophoblast, which secretes proteases like matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and hyaluronidase to erode the epithelial barrier and stromal extracellular matrix, forming lacunae by days 9 to 12 that connect to maternal capillaries for nutrient exchange.[32] Cytotrophoblast and extravillous trophoblast progenitors then proliferate, with the latter invading spiral arteries to remodel them, regulated by a balance of pro-invasive factors (e.g., cytokines like LIF and IL-1) and inhibitors (e.g., TIMPs, TGF-β) to prevent excessive penetration.[30] The trophoblast also produces human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), detectable post-implantation, which sustains the corpus luteum and progesterone production essential for pregnancy maintenance.[31] Disruptions in this protease-mediated invasion, often studied in IVF contexts, contribute to implantation failure rates exceeding 60% in assisted reproduction.[32]Early Patterning and Germ Layers

Gastrulation Dynamics

Gastrulation in the human embryo initiates approximately 14 days after fertilization, coinciding with the appearance of the primitive streak on the epiblast surface of the bilaminar disc, marking the onset of bilateral symmetry and the first major morphogenetic event.[33] This process transforms the simple epithelial layer into a trilaminar structure through coordinated cellular rearrangements, occurring primarily between days 15 and 21 post-fertilization.[4] The primitive streak forms caudally and elongates cranially, reaching up to half the embryo's length by Carnegie stage 7, driven by signaling gradients of Nodal, Wnt, and BMP pathways that induce epiblast cell fate changes and directed migration.[34] Central to gastrulation dynamics are epiblast cell movements, including ingression, where cells converge toward the primitive streak, undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and delaminate to migrate between the epiblast and hypoblast.[4] Ingression at the streak's primitive pit generates definitive endoderm by displacing the hypoblast, while laterally migrating cells form mesoderm; cranial ingress contributes to the prechordal plate and notochord precursors.[35] These movements involve convergence-extension, where cells intercalate mediolaterally to elongate the embryo anteroposteriorly, coupled with mechanical forces like actomyosin contractility that facilitate tissue deformation.[3] As the primitive streak regresses cranially from days 17-19, continued ingression produces progressively more anterior mesoderm derivatives, such as paraxial mesoderm, while posterior regions yield lateral plate and extraembryonic mesoderm.[4] Epiboly expands the remaining epiblast as ectoderm, thinning it over the embryo.[34] Disruptions in these dynamics, observable in rare human embryo samples and stem cell models, underscore the precision required, with failure linked to early pregnancy loss rates exceeding 50% at this stage.[36] Recent 3D imaging of gastrulating embryos reveals heterogeneous cell speeds and trajectories, with streak cells exhibiting up to 10-fold higher motility than surrounding epiblast.[37]Establishment of Three Germ Layers

The establishment of the three primary germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—occurs during gastrulation in the third week of human embryonic development, transforming the bilaminar embryonic disc into a trilaminar structure.[4][38] This process lays the spatial foundation for tissue and organ differentiation, with ectoderm forming the outer layer, mesoderm the middle, and endoderm the inner lining.[4] Gastrulation begins around day 15 post-fertilization with the appearance of the primitive streak, a transient structure on the caudal epiblast of the bilaminar disc, which defines the cranial-caudal axis.[4][38] Epiblast cells converge toward the streak, undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and ingress through it in a craniocaudal progression.[4] The first wave of ingressing cells displaces the hypoblast to form the definitive endoderm, which will contribute to the epithelial lining of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts.[4][38] Subsequent cells migrate laterally and cranially between the epiblast and endoderm, establishing the mesoderm, a layer that gives rise to connective tissues, muscles, and circulatory components.[4] The non-migrating epiblast cells differentiate into ectoderm, destined for epidermal and neural structures.[4] Notably, all three germ layers originate exclusively from the epiblast, while the hypoblast contributes primarily to extraembryonic membranes.[4][38] Midline ingression through the primitive node produces the prechordal plate and notochordal process, which are integral to axial mesoderm formation and future neural induction.[4] Signaling molecules such as Nodal, Wnt, BMP, and TGF-β orchestrate primitive streak induction, cell fate specification, and migration patterns.[4] By the end of week 3, the trilaminar disc is fully formed, marking the completion of germ layer establishment and the onset of organogenesis.[38] Direct observations in humans are limited due to ethical constraints, with much mechanistic insight derived from primate models and in vitro stem cell systems that recapitulate these events.[38]Neural and Axial Development

Neurulation and Neural Tube Closure

Neurulation in human embryos initiates during the third week post-fertilization, marking the primary phase of central nervous system formation through the transformation of the neural plate into the neural tube.[39] The process begins with the induction of neuroectoderm from overlying ectoderm by signals from the underlying notochord and paraxial mesoderm, leading to the thickening of the dorsal midline ectoderm into a pseudostratified columnar epithelium known as the neural plate.[40] This plate spans the length of the embryo, extending from the primitive node rostrally to the primitive streak caudally.[41] The neural plate undergoes shaping via convergent extension and apical constriction of neuroepithelial cells, elevating its lateral margins to form neural folds separated by a central neural groove.[39] Fusion of the neural folds commences in the cervical region around day 22, progressing bidirectionally: rostrally toward the forebrain and caudally toward the spinal cord.[40] The rostral neuropore, which will form the anterior end of the neural tube, closes on approximately day 25 at the 18- to 20-somite stage, while the caudal neuropore closes on day 28 at the 25-somite stage.[40] Completion of primary neurulation by the end of the fourth week establishes the primordial brain vesicles and spinal cord, with the neural tube lumen becoming the ventricular system and central canal.[39] During fold fusion, cells at the crest of the neural folds delaminate to form neural crest cells, which migrate laterally and differentiate into diverse derivatives including peripheral neurons, glia, melanocytes, and craniofacial skeleton components.[40] The apposing neural folds are initially connected by sutures of non-neural ectoderm that rupture to enclose the tube, a process regulated by molecular cues such as BMP signaling inhibition in the neural plate domain.[39] Failure of neural tube closure results in neural tube defects (NTDs), with anterior non-closure causing anencephaly and posterior defects leading to spina bifida or myelomeningocele.[42] Periconceptional folic acid supplementation reduces NTD incidence by 50-75%, though the precise mechanism—potentially involving DNA methylation, homocysteine metabolism, or planar cell polarity pathways—remains under investigation, with genetic factors contributing in folate-resistant cases.[43][44] Environmental influences, including maternal diabetes or valproate exposure, elevate risk independently of folate status.[39] Secondary neurulation, involving cavitation of a solid neural cord in the sacral region post-primary closure, accounts for the lowermost spinal cord segments but is less prone to defects.[40]Notochord and Somite Formation

The notochord originates during gastrulation in the third week of human embryonic development (approximately days 16-18 post-fertilization), when epiblast cells migrate through the primitive streak to form the primitive node at its cranial end.[45] Cells from the node ingress and form the notochordal process, which canalizes to create the notochordal canal before integrating with the endoderm to establish the definitive notochord.[45] This midline rod-like structure extends bidirectionally, starting from the embryo's middle and progressing cranially and caudally, thereby defining the primary body axis.[45] The notochord functions as an axial signaling center, secreting morphogens such as Sonic hedgehog (Shh) that pattern the overlying neural tube and induce adjacent mesoderm differentiation.[46][47] Somites arise from the paraxial mesoderm, which flanks the notochord and neural tube, with formation commencing around day 20 post-fertilization and continuing until approximately day 35-40.[48] Somitogenesis proceeds via sequential segmentation of the unsegmented presomitic mesoderm (PSM), governed by a molecular oscillator known as the segmentation clock, involving cyclic expression of genes in the Notch, Wnt, and FGF pathways that establish oscillatory signaling with a periodicity of about 90-120 minutes per somite pair in humans.[49][50] This clock interacts with a wavefront of FGF and Wnt gradients that define maturation zones in the PSM, leading to boundary formation through epithelialization and fissure creation at regular intervals.[49] Humans develop roughly 42-44 pairs of somites in total, with anterior somites forming first and the process yielding transient epithelial spheres that later differentiate.[51] The notochord plays a critical inductive role in somite patterning, particularly by secreting Shh from its ventral-medial aspect to specify the sclerotome—the ventral somite region destined for vertebral and rib cartilage formation—while inhibiting lateral plate mesoderm fate in paraxial mesoderm.[47] Somites further compartmentalize into dermatome (dorsolateral, forming dermis), myotome (epaxial and hypaxial, yielding skeletal muscles), and sclerotome, with combinatorial signals from the notochord, neural tube floor plate, and surface ectoderm refining these fates.[47] As development advances, the notochord regresses, with remnants persisting as the nucleus pulposus in intervertebral discs, while somite derivatives contribute to the musculoskeletal axis.[52] Disruptions in notochord-somite signaling, such as altered Shh expression, can lead to axial skeletal defects like spina bifida or scoliosis precursors.[47]Organogenesis by System

Cardiovascular System Initiation

The cardiovascular system begins forming during the third week of human embryonic development, with cardiogenic mesoderm specified from the lateral plate mesoderm as early as the end of the second week during gastrulation (Carnegie Stage 7, approximately 15-16 days post-fertilization).[53] This mesoderm arises from bilateral cardiac progenitor fields in the splanchnic layer, influenced by signaling from the anterior visceral endoderm and underlying hypoblast, which induce cardiac fate through pathways like BMP, FGF, and Wnt inhibition.[54] By day 18-19, these progenitors migrate cranially and laterally, forming a horseshoe-shaped cardiac crescent comprising the first heart field (FHF) for initial linear tube components and the second heart field (SHF) for later additions like the outflow tract.[55] Fusion of the bilateral endocardial tubes occurs midline around day 20-21 (Carnegie Stage 9-10), establishing the primitive heart tube, which elongates through addition of SHF cells and begins peristaltic contractions.[53] [56] The first detectable heartbeat, marking the onset of circulation, typically initiates between 21 and 23 days post-fertilization (around 5 weeks gestational age), with rates increasing from 65 beats per minute to over 150 by the end of the fourth week; earlier calcium transients suggesting pre-beat activity around day 16 remain debated but do not constitute functional pumping.[57] [58] Simultaneously, vasculogenesis establishes intraembryonic endothelial networks from angioblasts, while extraembryonic angiogenesis forms the yolk sac vasculature by day 17-18, enabling initial nutrient exchange prior to full cardiac function.[59] Molecular drivers include transcription factors such as Nkx2.5 and Gata4 in FHF progenitors, with Tbx5 regulating chamber specification; disruptions in these, as seen in congenital models, underscore the precision of this phased initiation.[60] By the end of week 4, looping of the heart tube begins, setting the stage for septation and chamber formation, though the system remains dependent on diffusion until circulation fully activates.[53]Nervous System Differentiation

Following neural tube closure at the end of the fourth gestational week, the central nervous system undergoes initial differentiation through regional expansion and flexure of the neural tube. The rostral end forms the cephalic flexure between days 23 and 26, orienting the developing forebrain ventrally, while a pontine flexure emerges later in the hindbrain region. This process establishes anterior-posterior and dorsoventral axes essential for subsequent compartmentalization.[61] By the fifth week, the rostral neural tube dilates into three primary brain vesicles: the prosencephalon (forebrain), mesencephalon (midbrain), and rhombencephalon (hindbrain). The prosencephalon further subdivides around week 6 into the telencephalon, which gives rise to cerebral hemispheres, and the diencephalon, precursor to the thalamus and hypothalamus. The rhombencephalon segments into the metencephalon (pons and cerebellum) and myelencephalon (medulla oblongata) by week 7, with the mesencephalon remaining undivided as the midbrain. These vesicles exhibit distinct gene expression patterns, such as OTX2 in fore- and midbrain regions and HOX genes in hindbrain, driving morphological divergence.[61][62] The spinal cord, extending from the caudal neural tube, differentiates along its dorsoventral axis starting in week 5. The basal plate ventrally produces motor neurons that migrate to form anterior (ventral) horns, while the alar plate dorsally generates interneurons and sensory relays, separated by the sulcus limitans. By week 8, initial neurogenesis yields postmitotic neurons, with gliogenesis following later; the ependymal layer lining the central canal retains progenitor potential. Cavitation and mantle layer formation support neuronal migration and lamination.[61][39] Peripheral nervous system components arise primarily from neural crest cells, which delaminate from the dorsal neural tube between weeks 3 and 5. These migratory cells populate sites to form sensory ganglia (dorsal root and cranial), autonomic ganglia, Schwann cells for myelination, and melanocytes. Trunk neural crest differentiates into sensory and sympathetic neurons, while cranial crest contributes to parasympathetic structures and facial skeleton via mesenchymal transition. Placodes provide additional sensory neuron contributions, such as in trigeminal and vestibulocochlear ganglia.[61][63] Early synaptic connections emerge by week 7, with spontaneous activity in spinal motor circuits detectable via ultrasound around gestational week 9, indicating functional maturation. Disruptions in differentiation, such as folate deficiency impacting neural crest migration, underscore the precision of these spatiotemporal events.[61][64]Digestive and Respiratory Primordia

The primitive gut tube, derived from the definitive endoderm following gastrulation, begins to form during the third week of embryonic development through cephalic and caudal folding of the embryo, incorporating portions of the yolk sac into a continuous tubular structure extending from the oropharyngeal membrane to the cloacal membrane.[65] This tube initially lacks regional specialization but differentiates into three distinct primordia—foregut, midgut, and hindgut—by the end of the fourth week, corresponding to Carnegie stages 11 through 13 (approximately days 23 to 32 post-fertilization).[66] [67] The foregut primordium, located cranially, gives rise to the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, proximal duodenum (up to the major duodenal papilla), liver, pancreas, and biliary apparatus, with its ventral wall also contributing to the respiratory system.[65] The midgut extends from the distal foregut to the junction with the hindgut at the level of the distal transverse colon, forming the distal duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, appendix, ascending colon, and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon; it undergoes rapid elongation during the fifth week, leading to physiological herniation into the umbilical cord between weeks 6 and 10 before returning to the abdominal cavity.[65] [68] The hindgut primordium forms the distal third of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and upper anal canal, continuous with the allantois and eventually incorporating ectodermal contributions at the cloacal membrane.[65] Respiratory primordia emerge concurrently from the ventral aspect of the foregut during the fourth week, around day 22 to 28, as a single median outgrowth termed the respiratory diverticulum or lung bud, which elongates caudally into surrounding splanchnic mesoderm to initiate tracheobronchial tree formation.[69] [70] By the end of week 4, this diverticulum bifurcates into left and right bronchial buds, which further branch to establish the conducting airways, while the trachea separates from the esophagus via tracheoesophageal ridges; these structures are endodermally lined, with mesodermal contributions forming cartilage, muscle, and connective tissue.[69] [71] Disruptions in these early partitioning events can lead to anomalies such as tracheoesophageal fistula, underscoring the precise spatiotemporal coordination required.[69]Urogenital System Development

The urogenital system originates from the intermediate mesoderm, which forms during the third week of embryonic development as a longitudinal strip between the paraxial and lateral plate mesoderm. By the fourth week, this mesoderm differentiates into the nephrogenic cord and the adjacent gonadal ridge, collectively elevating as the urogenital ridge along the posterior abdominal wall. The urinary and genital components develop interdependently, with shared primordia such as the mesonephric ducts influencing both systems.[72][73] Urinary tract development proceeds through three sequential nephric stages within the nephrogenic cord. The pronephros emerges first around day 22 (week 4), forming rudimentary tubules in the cervical region that connect to the pronephric duct but regress by the end of week 4 without functional contribution in humans. The mesonephros follows caudally from days 24 to 28 (late week 4), producing approximately 40 pairs of tubules that temporarily handle excretion and fluid balance until week 8, after which most regress, though remnants persist as structures like the epoophoron in females and paradidymis in males. The definitive metanephros initiates at week 5 when the ureteric bud sprouts from the mesonephric (Wolffian) duct and penetrates the metanephric mesenchyme (blastema), inducing reciprocal signaling via factors such as GDNF and WT1 to form collecting ducts, nephrons, and renal pelvis; glomerular filtration begins by week 10, with the kidney ascending from pelvic to lumbar position by week 9 due to differential growth.[74][73] The bladder and urethra derive from the cloaca, an endodermal pouch divided by the urorectal septum between weeks 4 and 7 into the ventral urogenital sinus and dorsal anorectal canal. The allantois incorporates into the urogenital sinus to form the bladder apex, while ureteral buds insert into the sinus wall by week 6, establishing the trigone; the urethra elongates from the sinus, with the urachus remnant becoming the median umbilical ligament. Congenital anomalies like renal agenesis arise from failed ureteric bud-metenchyme interaction, underscoring the precision of these inductive events.[74] Gonadal development begins with thickening of the urogenital ridge into the genital ridge by week 5, colonized by primordial germ cells migrating from the yolk sac via the hindgut endoderm around weeks 4-5. Until week 7, the gonad remains indifferent, featuring epithelial proliferation and mesenchymal cores. Sexual differentiation is triggered genetically at fertilization (XX or XY karyotype) but manifests phenotypically by week 7: in XY embryos, SRY gene expression on the Y chromosome upregulates SOX9 in Sertoli cell precursors, promoting testis cord formation and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) secretion by week 8 to regress paramesonephric (Müllerian) ducts; testosterone from Leydig cells by week 9 stabilizes mesonephric (Wolffian) ducts into epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicles. In XX embryos, absence of SRY leads to ovarian differentiation by week 10-12, with FOXL2-driven granulosa cells; Wolffian ducts regress due to lack of androgens, while Müllerian ducts fuse and elongate to form fallopian tubes, uterus, and upper vagina by week 12.[72][75] External genitalia arise from the cloacal membrane and genital swellings by week 4, remaining bipotential until weeks 9-12 when dihydrotestosterone drives male differentiation (phallus elongation, scrotal fusion) versus estrogen-independent female development (labioscrotal folds as labia). Disruptions in these pathways, such as SRY mutations, can lead to disorders of sex development, highlighting the system's sensitivity to molecular cues.[72][75]Musculoskeletal and Integumentary Foundations

The musculoskeletal system's foundational structures emerge from the paraxial mesoderm, which undergoes somitogenesis starting in the third week of development, approximately 19-20 days post-fertilization.[76] Somites form sequentially in a caudal direction from presomitic mesoderm, driven by oscillatory gene expression involving Notch, Wnt, and FGF signaling pathways that establish segmentation clocks.[77] In humans, somitogenesis produces 42-44 pairs of somites by the end of the embryonic period, with the process spanning weeks 3 to 5.[78][79] Each somite differentiates into three primary components: the ventral sclerotome, which migrates around the notochord and neural tube to form mesenchymal condensations that give rise to the axial skeleton including vertebrae, ribs, and associated cartilage; the medial and lateral portions of the dermomyotome, which split to form the myotome contributing to skeletal muscle precursors and the dermatome yielding dermal connective tissue.[47][80] Sclerotomal cells express Pax1 and Sox9, initiating chondrogenesis around weeks 5-6, while myotomal cells delaminate and proliferate under Myf5 and MyoD regulation to form myoblasts for epaxial (dorsal) and hypaxial (ventral) muscle groups.[81] These early mesenchymal aggregates represent the primordia for ossification centers that appear later in the fetal period, with initial cartilage models forming by week 6.[82] Appendicular musculoskeletal elements originate from somatopleuric mesoderm in the limb buds, which emerge around day 26 for the upper limbs and day 28 for the lower, with somitic myotomal cells migrating into these buds to populate future limb muscles while lateral plate mesoderm forms the skeletal anlagen.[80] The integumentary system's epidermis derives from surface ectoderm, which thickens into a pseudostratified layer by the end of week 4 following neural tube closure, subsequently developing a superficial periderm of flattened cells by week 8 to protect the underlying basal layer.[83] Dermal foundations arise from mesodermal mesenchyme, including contributions from the somitic dermatome dorsally and lateral plate mesoderm ventrally, forming loose connective tissue that interacts with overlying ectoderm via BMP and Wnt signals to induce stratification and appendage formation.[84] By week 8, the dermis contains fibroblasts producing collagen and elastin precursors, establishing the structural matrix for epidermal basement membrane attachment and future hypodermal fat development.[85] These dual-layer origins ensure coordinated growth, with ectodermal proliferation outpacing dermal vascularization initially, leading to avascular epidermal coverage in early embryos.[86]Craniofacial and Limb Morphogenesis

Head and Neck Structures

The pharyngeal arches, also known as branchial arches, form the foundational structures for the head and neck during human embryonic development, appearing as paired mesodermal swellings surrounding the foregut from approximately day 20 to day 35 of gestation.[87] These arches develop in a craniocaudal sequence during the third and fourth weeks, with the first arch emerging around day 22, followed by the second on day 24, and subsequent arches (third, fourth, and sixth; the fifth is rudimentary or absent) by the end of the fourth week.[88] Each arch consists of a mesenchymal core derived largely from neural crest cells, externally covered by ectoderm and internally lined by endoderm, separated externally by pharyngeal clefts and internally by pouches.[89] The first pharyngeal arch contributes to the mandible, maxilla, malleus, incus, and muscles of mastication, while the second forms parts of the hyoid bone, stapes, styloid process, and facial expression muscles.[89] The third and fourth arches give rise to additional hyoid components, the thymus, parathyroids, and laryngeal structures, with the sixth arch contributing to laryngeal cartilage and muscles.[89] Pharyngeal pouches derive endodermal structures such as the tympanic cavity from the first, tonsillar fossa from the second, thymus and inferior parathyroid from the third, and superior parathyroid and ultimobranchial body from the fourth.[89] The external clefts largely obliterate, except the first which persists as the external auditory meatus, while caudal clefts form a temporary cervical sinus that normally regresses by week 7.[89] Facial structures arise from the integration of pharyngeal arch derivatives with the frontonasal prominence during weeks 4 to 7, where the frontonasal region forms the forehead and nasal structures via medial and lateral nasal prominences, and the maxillary prominences from the first arch develop the upper cheek and lip, fusing with mandibular prominences to form the lower jaw.[89] Neck elongation occurs concurrently with the descent of structures like the thymus and thyroid from pharyngeal regions, establishing the definitive cervical anatomy by the eighth week.[90] Neural crest mesenchyme migration into these regions is essential for skeletogenic and odontogenic differentiation, underscoring the arches' role in craniofacial morphogenesis.[91] Disruptions in arch formation or fusion can lead to congenital anomalies such as branchial cysts or craniofacial dysostoses, highlighting the precision of these developmental processes.[89]Sensory Organ Ontogeny

The ontogeny of sensory organs in the human embryo arises predominantly from specialized ectodermal placodes induced by interactions with underlying mesenchyme and neural crest cells during weeks 4 through 8 post-fertilization. These structures, including the optic, otic, and olfactory placodes, emerge as thickenings of the cranial ectoderm and give rise to the retina, cochlea-vestibular apparatus, and olfactory epithelium, respectively, while middle and external ear components derive from pharyngeal arches.[92][93] Gustatory structures develop later from endodermal and ectodermal contributions in the oral cavity. This process is regulated by conserved signaling pathways such as BMP, FGF, and Wnt, ensuring patterned differentiation amid rapid craniofacial morphogenesis.[94] Eye development initiates at approximately 22 days post-fertilization (week 4), with optic grooves forming along the anterolateral neural plate, followed by evagination of optic vesicles from the diencephalon.[95] These vesicles contact the overlying surface ectoderm by the end of week 4, inducing lens placode formation through secretion of factors like FGF from the optic vesicle; the placode invaginates to form the lens vesicle, separating from the ectoderm by week 5.[92] Concurrently, the optic vesicle invaginates to create the double-layered optic cup, whose inner layer differentiates into the neural retina and outer into the retinal pigment epithelium, with hyaloid vessels supplying the early structure.[92] By week 7, corneal endothelium and stroma begin forming from neural crest and mesenchyme, while iris and ciliary body primordia emerge from the optic cup margin; eyelids appear as folds around week 7, fusing by week 10 to protect the developing globe.[96] Ear ontogeny commences slightly earlier, with otic placodes thickening from ectoderm adjacent to the hindbrain rhombomeres 5-6 around week 3 (day 22).[93] These placodes invaginate into otic pits by late week 4, pinching off to form otic vesicles (otocysts), which elongate and differentiate into the membranous labyrinth: the ventral portion develops into the cochlear duct by week 8, while dorsal regions form semicircular canals for vestibular function between weeks 6-8.[93][97] The middle ear ossicles (malleus, incus) arise from mesenchymal condensations in the first and second pharyngeal arches by week 6, cartilaginizing and beginning ossification in the embryonic period, whereas the external auditory meatus derives from the first pharyngeal cleft, canalizing by week 8.[93] Auricular hillocks, six in total from arches 1-2 and 3, appear around week 5 on the mandibular and hyoid arches, fusing to form the pinna by week 8.[98] Olfactory organ development begins around week 5 with bilateral olfactory (nasal) placodes on the frontonasal prominence, which invaginate to form nasal pits and sacs, separating the prospective olfactory epithelium from respiratory mucosa.[99] By Carnegie stage 16 (week 5), the nasal fin thins into the oronasal membrane, which ruptures by stage 18 (week 6) to connect nasal and oral cavities; olfactory axons extend from receptor neurons in the epithelium toward the forebrain, evoking the olfactory bulb primordium at stage 18.[99][100] The bulb laminates into glomerular, mitral, and granular layers by week 14, though functional maturation, including glomeruli formation, continues into the fetal period.[101] Gustatory primordia, including taste pores in lingual epithelium, emerge around week 8 from local ectodermal thickenings influenced by cranial nerves VII, IX, and X.[94] Disruptions in placode induction or migration, often linked to genetic factors like FOXG1 mutations, can yield anomalies such as anophthalmia or choanal atresia.[102]Limb Bud Outgrowth and Patterning