Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

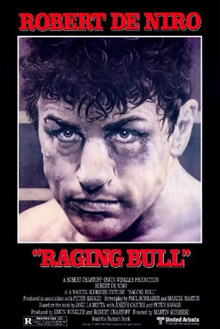

Raging Bull

View on Wikipedia

| Raging Bull | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Tom Jung | |

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | Robert De Niro |

| Cinematography | Michael Chapman |

| Edited by | Thelma Schoonmaker |

Production companies | Chartoff-Winkler Productions, Inc.[1] |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 129 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $18 million[3] |

| Box office | $23.4 million[3] |

Raging Bull is a 1980 American biographical sports drama film directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, Cathy Moriarty, Theresa Saldana, Frank Vincent and Nicholas Colasanto (in his final film role). The film is an adaptation of former middleweight boxing champion Jake LaMotta's 1970 memoir Raging Bull: My Story. It follows the career of LaMotta (played by De Niro), his rise and fall in professional boxing, and his turbulent personal life beset by rage and jealousy.

Scorsese was initially reluctant to develop the project, although he eventually came to relate with LaMotta's story. Paul Schrader rewrote Mardik Martin's first screenplay, and Scorsese and De Niro together made uncredited contributions thereafter. Pesci was a relatively unknown actor prior to the film, as was Moriarty, whom Pesci suggested for her role. During principal photography, each of the boxing scenes was choreographed for a specific visual style, and De Niro gained approximately 60 pounds (27 kg) to portray LaMotta in his later years.

Scorsese was exacting in the process of editing and mixing the film, expecting it to be his last major feature. Scorsese closely studied Luchino Visconti's Rocco and His Brothers, especially the way the fight scenes are filmed, a technique he integrated into Raging Bull.[4][5][6] In addition, Scorsese was inspired by the character of Rocco (Alain Delon played the professional boxer) to help shape De Niro's interpretation of Jake LaMotta.[7][8][9]

Raging Bull premiered in New York City on November 14, 1980, and was released in theaters on December 19, 1980. The film had a lukewarm box office of $23.4 million against its $18 million budget. The film received mixed reviews on its release. While De Niro's performance and the editing were widely acclaimed, its violent content received criticism. Despite the mixed reviews, the film was nominated for eight Academy Awards at the 53rd Academy Awards (tying with The Elephant Man as the most nominated film of the ceremony), including Best Picture and Best Director, and won two: Best Actor for De Niro (his second Oscar) and Best Editing.

After its release, Raging Bull went on to receive high critical praise, and is now considered one of the greatest films ever made. In 1990, it became the first film to be selected in its first year of eligibility for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant",[10][11] and the American Film Institute ranked it as the fourth-greatest American movie of all time.

Plot

[edit]In 1941, Jake LaMotta is a young up-and-coming middleweight boxer who suffers his first loss to Jimmy Reeves after a controversial decision. Jake's brother Joey discusses a potential shot for the middleweight title with one of his Mafia connections, Salvy Batts. Still, he repeatedly refuses the Mafia's help, wanting to win the championship on his terms.

Jake spots a 15-year-old girl named Vickie at a swimming pool in his Bronx neighborhood. He eventually pursues a relationship with her, despite his being already married and Vickie being underage. In 1943, Jake defeats Sugar Ray Robinson, and has a rematch three weeks later. Despite Jake dominating Robinson during the bout, the judges surprisingly rule in favor of Robinson, who Joey feels won only because he was enlisting in the Army the following week.

By 1945, Jake marries Vickie, but he is controlling and domineering over her, and constantly worries that she has feelings for other men. His jealousy is evident when he brutally beats his next opponent, Tony Janiro, in front of Tommy Como, the local mob boss, and Vickie. As Joey discusses the victory with journalists at the Copacabana, he is distracted by seeing Vickie approach a table with Salvy and his crew. Joey speaks with Vickie, who implies that she is dissatisfied in her marriage with Jake. Under the mistaken impression that Vickie is having an affair with Salvy, Joey viciously attacks him in a fight that spills outside of the club.

Como orders them to apologize to each other, but has Joey tell Jake that if he wants a chance at the championship title, which Como controls, he will have to take a dive. Jake purposely loses his next match against Billy Fox, and is booed out of the building after putting up a lackluster performance. He is suspended from the board shortly thereafter on suspicion of throwing the fight. He is reinstated and, in 1949, wins the middleweight championship title against Marcel Cerdan.

In 1950, Jake becomes increasingly paranoid that Vickie is having an affair. He asks Joey if he has had an affair with her, which enrages Joey and causes him to leave. Jake presses Vickie about whether she has had an affair, leading to her sarcastically confessing that she had sex with Joey, Salvy, and Tommy. In a fit of rage, Jake, followed by Vickie, walks to Joey's house and assaults him in front of his wife, Lenora, and their children before knocking Vickie unconscious.

Vickie returns to their home and threatens to leave, but they reconcile. After defending his championship belt in a grueling 15-round bout against Laurent Dauthuille in 1950, he calls his brother after the fight to make amends. Still, when Joey assumes that Salvy is on the other end and starts insulting him, Jake silently hangs up. Estranged from his brother, Jake sees his career decline, and he eventually loses his title to Sugar Ray Robinson in their final encounter in 1951.

By 1956, an aging and overweight Jake has retired and moved with his family to Miami. After he stays out all night at the nightclub that he owns, Vickie tells him that she wants a divorce, as well as full custody of their children. She also threatens to call the police if he comes anywhere near them.

Jake is arrested for admitting underage girls to his nightclub, and he unsuccessfully attempts to bribe his way out of his criminal case using the jewels from his championship belt. In 1957, he goes to jail, sorrowfully questioning his misfortune and crying in despair. After returning to New York City in 1958, he encounters Joey, whom he forcefully embraces. Joey half-heartedly reciprocates.

In 1964, Jake performs stand-up comedy at various clubs. Backstage before a show, LaMotta prepares for his performance by shadowboxing, quoting scenes from On the Waterfront and chanting "I'm the boss" before taking the stage.

Cast

[edit]- Robert De Niro as Jake LaMotta[12]

- Joe Pesci as Joey LaMotta[12]

- Cathy Moriarty as Vickie LaMotta[12]

- Nicholas Colasanto as Tommy Como[12]

- Theresa Saldana as Lenora LaMotta, Joey's second wife[12]

- Frank Vincent as Salvatore "Salvy Batts"[12]

- Lori Anne Flax as Irma LaMotta, Jake's first wife

- Mario Gallo as Mario

- Frank Adonis as "Patsy"

- Joseph Bono as Guido

- Frank Topham as "Toppy"

- Charles Scorsese as Charlie

- Geraldine Smith as Janet

- Candy Moore as Linda

- James V. Christy as Dr. Pinto

- Laura James as Mrs. Bronson

- Peter Savage as Jackie Curtie

- Don Dunphy as Himself

- McKenzie Westmore as Stephanie LaMotta

- Gene LeBell as Ring Announcer for Reeves Fight

- Shay Duffin as Ring announcer for Janiro Fight

- Martin Scorsese as Barbizon Stagehand (voice)

- Michael Badalucco as Soda Fountain Clerk

- John Turturro as Man at Webster Hall Table (uncredited)

- Coley Wallace as Joe Louis[13]

LaMotta's opponents

[edit]- Johnny Barnes as Sugar Ray Robinson

- Bill Hanrahan as Eddie Eagan

- Kevin Mahon as Tony Janiro

- Eddie Mustafa Muhammad as Billy Fox

- Floyd Anderson as Jimmy Reeves

- Johnny Turner as Laurent Dauthuille

- Louis Raftis as Marcel Cerdan

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Raging Bull was initiated when Robert De Niro read the autobiography while he was on the set of The Godfather Part II. Although disappointed by the book's writing style, De Niro became fascinated by the character of Jake LaMotta. He showed the book to Martin Scorsese on the set of Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, with the hope that he would consider the project.[14]

Scorsese repeatedly turned down the opportunity to direct the film, claiming that he had no idea what Raging Bull was about, although he had read some of the text. Never a sports fan, when he found out what LaMotta used to do for a living, he said, "A boxer? I don't like boxing...Even as a kid, I always thought that boxing was boring... It was something I couldn't, wouldn't grasp." His overall opinion of sport in general is, "Anything with a ball, no good."[15]

The book was passed on to Mardik Martin, the film's eventual co-screenwriter, who said, "The trouble is the damn thing has been done a hundred times before—a fighter who has trouble with his brother and his wife and the mob is after him." De Niro had even shown the book to producers Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler, who were willing to assist only if Scorsese agreed.[16]

After nearly dying from a drug overdose, Scorsese agreed to make the film, not only to save his own life but also to save his career. Scorsese began to relate very personally to the story of Jake LaMotta, and in it, he saw how the boxing ring can be "an allegory for whatever you do in life", which for him paralleled moviemaking: "You make movies, you're in the ring each time."[17][18][19][20]

Preparation for the film began when Scorsese shot some 8 mm color footage featuring De Niro boxing in a ring. One night, when the footage was being shown to De Niro, Michael Chapman and his friend and mentor, the British director Michael Powell, Powell pointed out that the color of the gloves at the time would have been only maroon, oxblood or black. It is one of the reasons that Scorsese chose to film Raging Bull in black and white. Other reasons were to distinguish the film from color films at the time, and to acknowledge the problem of fading color film stock—an issue that Scorsese recognized.[21][22][23] Scorsese attended two matches at Madison Square Garden to aid his research, picking up on minor but essential details, such as the blood sponge and subsequently, the blood on the ropes (which would be used in the film).[23]

According to the brief comments on the inlay card of the DVD, Scorsese was not a fan of sports nor boxing, which he describes as boring. When he saw the blood-soaked sponges being dipped in a bucket, he recalls thinking, "And they call this sport".

Multiple titles were considered for Raging Bull, including Prizefighter and The Jake La Motta Story. Scorsese stated that Prizefighter was his favorite title, but did not select it, for he was afraid that people would think that the film was solely about boxing.[24]

Screenplay

[edit]Under the guidance of Chartoff and Winkler, Mardik Martin was asked to start writing the screenplay.[25] According to De Niro, under no circumstances would United Artists accept Martin's script.[26] The story was based on the vision of journalist Pete Hamill of a 1930s and 1940s style, when boxing was known as "the great dark prince of sports". De Niro, however, was unimpressed when he finished reading the first draft.[27]

Taxi Driver screenwriter Paul Schrader was swiftly brought in to rewrite the script around August 1978.[27] Some of the changes that Schrader made to the script include a rewrite of the scene with the undercooked steak, and the inclusion of LaMotta seen masturbating in a Florida cell.

The character of LaMotta's brother Joey was finally added, previously absent from Martin's script.[26][27] United Artists saw a massive improvement on the quality of the script. However, its chief executives Steven Bach and David Field met with Scorsese, De Niro and producer Irwin Winkler in November 1978 to say that they were worried that the content would be X-rated material and have no chance of finding an audience.[21]

According to Scorsese, the script was left to him and De Niro, and they spent two-and-a-half weeks on the island of Saint Martin extensively re-building the content of the film.[17] The most significant change would be the scene in which LaMotta fixes his television and accuses his wife of having an affair.

Other changes included the removal of Jake and Joey's father, the reduction of organized crime's role in the story, and a major rewrite of LaMotta's fight with Tony Janiro.[28][29] They were also responsible for the end sequence in which LaMotta is alone in his dressing room, quoting "I could have been a contender" from On the Waterfront.[29] An extract of Richard III had been considered, but Michael Powell thought that it would be a bad decision within the context of an American film.[17] According to Steven Bach, the first two screenwriters (Martin and Schrader) would receive credit, but since there was no payment to the writer's guild on the script, De Niro and Scorsese's work remained uncredited.[29]

Casting

[edit]

One of Scorsese's trademarks was casting many actors and actresses new to the profession.[30] De Niro, who was already committed to play Jake LaMotta, began to help Scorsese track down unfamiliar names to play his on-screen brother Joey and wife Vikki.[31][32] The role of Joey LaMotta was the first to be cast. De Niro was watching a low-budget television film called The Death Collector when he saw the part of a young career criminal played by a relatively-unknown Joe Pesci as an ideal candidate. Prior to receiving a call from De Niro and Scorsese for the proposal to star in the film, Pesci had not worked in film for four years and was working at an Italian restaurant in New Jersey.

The role of Vikki (spelled "Vickie" in the final film), Jake's second wife, had interest across the board, but it was Pesci who suggested the unknown Cathy Moriarty from a picture that he saw at a New Jersey disco.[32] Both De Niro and Scorsese believed that Moriarty, at 18 years old, could portray the role after meeting with her on several occasions and noticing her husky voice and physical maturity. The duo had to prove to the Screen Actors Guild that she was right for the role when Cis Corman showed 10 comparing pictures of Moriarty and the real Vikki LaMotta for proof that she had a resemblance.[32]

Moriarty was asked to take a screen test, which she managed—partly aided by some improvised lines from De Niro—after some confusion wondering why the crew was filming her take. Joe Pesci also persuaded his former show-biz pal and co-star in The Death Collector, Frank Vincent, to audition for the role of Salvy Batts. Following a successful audition and screen test, Vincent received the call to say that he had received the part.[33] Charles Scorsese, the director's father, made his film debut as Tommy Como's cousin Charlie.[33]

While in the midst of practicing a Bronx accent and preparing for his role, De Niro met with both LaMotta and his ex-wife Vikki on separate occasions. Vikki, who lived in Florida, told stories about her life with her former husband, and showed old home movies (that later inspired a similar sequence to be done for the film).[22][34]

Jake LaMotta, on the other hand, served as his trainer, accompanied by Al Silvani as coach at the Gramercy club in New York City, getting him into shape. The actor found that boxing came naturally to him; he entered as a middleweight boxer, winning two of his three fights in a Brooklyn ring dubbed "young LaMotta" by the commentator. According to Jake LaMotta, De Niro was one of the top 20 best middleweight boxers of all time.[22][32]

Principal photography

[edit]

According to the sound mixer, Michael Evje, the film began shooting at the Los Angeles Olympic Auditorium on April 16, 1979. Grips hung huge curtains of black duvetyne on all four sides of the ring area to contain the artificial smoke used extensively for visual effect.

On May 7, the production moved to the Culver City studio, Stage 3, and filmed there until the middle of June. Scorsese made it clear during filming that he did not appreciate the traditional way of showing fights from the spectators' view.[23] He insisted that one camera operated by the Director of Photography, Michael Chapman, would be placed inside of the ring, as he would play the role of an opponent keeping out of the way of other fighters, so that viewers could see the emotions of the fighters, including those of Jake.[32]

The precise moves of the boxers were to be done as dance routines from the information of a book about dance instructors in the mode of Arthur Murray. A punching bag in the middle of the ring was used by De Niro between takes before he aggressively came straight on to do the next scene.[32][35] The initial five-week schedule for the shooting of the boxing scenes took longer than expected, putting Scorsese under pressure.[32]

According to Scorsese, production of the film was closed for nearly four months with the entire crew being paid, so that De Niro could go on a binge-eating trip around northern Italy and France.[22][35] When he arrived in the United States, his weight had increased from 145 to 215 pounds (66 to 97 kg).[32] The scenes with the heftier Jake LaMotta—which include announcing his retirement from boxing and LaMotta in a Florida cell—were completed seven-to-eight weeks later when approaching Christmas 1979, so as not to aggravate the health issues that were affecting De Niro's posture, breathing and talking.[32][35][36]

According to Evje, Jake's nightclub sequence was filmed in a closed San Pedro club on December 3. The jail cell head-banging scene was shot on a constructed set, with De Niro asking for minimal crew to be present. There was not even a boom operator present.[citation needed]

The final sequence, in which Jake LaMotta is in front of his mirror, was filmed on the last day of shooting, requiring 19 takes, with only the 13th being used for the film. Scorsese wanted to have an atmosphere that would be so cold that the words would have an impact as he tries to come to terms with his relationship with his brother.[17]

Post-production

[edit]The editing of Raging Bull began when production was temporarily put on hold and was completed in 1980.[35][37] Scorsese worked with the editor Thelma Schoonmaker to achieve a final cut of the film. Their main decision was to abandon Schrader's idea of LaMotta's nightclub act interweaving with the flashback of his youth, and instead followed the lines of a single flashback, in which only scenes of LaMotta practicing his stand-up would remain bookending the film.[38]

A sound mix arranged by Frank Warner was a delicate process that took six months.[37] According to Scorsese, the sound on Raging Bull was difficult because each punch, camera shot and flash bulb would be different. Also, there was the issue of trying to balance the quality between scenes featuring dialogue and those involving boxing (which were done in Dolby Stereo).[35] Raging Bull went through a test screening in front of a small audience including the chief executives of United Artists, Steven Bach and Andy Albeck. The screening was shown at the M-G-M screening room in New York in July 1980. Albeck praised Scorsese by calling him a "true artist".[37]

According to the producers Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler, matters were made worse when United Artists decided not to distribute the film but no other studios were interested when they attempted to sell the rights.[37] Scorsese made no secret that Raging Bull would be his "Hollywood swan song" and he took unusual care of its rights during post-production.[18] Scorsese threatened to remove his credit from the film if he was not allowed to sort a reel that obscured the name of a whisky brand (Cutty Sark) that was heard in a scene. The work was completed four days shy of the premiere.[39]

In 2012, Raging Bull was voted by the Motion Picture Editors Guild as the best-edited film in history.[40]

Copyright litigation

[edit]Paula Petrella, heir to Frank Petrello, whose works were allegedly sources for the film, filed for copyright infringement in 2009 based on MGM's 1991 copyright renewal of the film. In 2014, the Supreme Court held, in Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., that Petrella's suit survived MGM's defense of "laches", the legal doctrine that protects defendants from unreasonable delays by potential plaintiffs. The case was remanded to lower courts, meaning that Petrella could receive a decision on the merits of her claim.[41] MGM settled with Petrella in 2015.[42]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The brew of violence and anger, combined with the lack of a proper advertising campaign, led to the film's lukewarm box-office intake of $23 million, compared to its $18 million budget. By the time it left theaters, it earned $10.1 million in theatrical rentals (equivalent to $32.2 million in 2024).[43] Scorsese became concerned for his future, and worried that producers and studios may refuse to finance his films.[44] According to Box Office Mojo, the film grossed $23,383,987 in domestic theaters (equivalent to $74.5 million in 2024).[45]

Critical response

[edit]When it premiered in New York City on November 14, 1980, the release of Raging Bull was met with polarized reviews, but the film would receive widespread critical acclaim, and is widely regarded as one of Scorsese's best works.[37][38]

On the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 92% based on 151 reviews, with an average rating of 9.00/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Arguably Martin Scorsese's and Robert De Niro's finest film, Raging Bull is often painful to watch, but it's a searing, powerful work about an unsympathetic hero."[46] Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average, gave it a score of 90 out of 100, based on 28 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[47] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on a scale of A+ to F.[48]

Jack Kroll of Newsweek called Raging Bull the "best movie of the year".[37]

Critic for The New Yorker, Pauline Kael described the film not as a biographical film about a boxer, but as a "biography of the genre of prize fighting" further saying the film is "tabloid grand opera" and "overripe, ready for canonization" in which Scorsese puts his "unmediated obsessions on the screen."[49]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times said that Scorsese "has made his most ambitious film as well as his finest", and went on to praise Moriarty's debut performance, saying, "Either she is one of the film finds of the decade or Mr. Scorsese is Svengali. Perhaps both."[50][44]

Time praised De Niro's performance because "much of Raging Bull exists because of the possibilities it offers De Niro to display his own explosive art".[44]

Steven Jenkins from the British Film Institute's (BFI) magazine Monthly Film Journal said that "Raging Bull may prove to be Scorsese's finest achievement to date".[44]

Accolades

[edit]The Oscars were held the day after President Ronald Reagan was shot by John Hinckley, who did it as an attempt to impress Jodie Foster, who played a child prostitute in another of Scorsese's famous films, Taxi Driver (which also starred De Niro).[53] Out of fear of being attacked, Scorsese went to the ceremony with FBI bodyguards disguised as guests who escorted him before the announcement of the Academy Award for Best Picture was made (the winner being Robert Redford's Ordinary People).

The Los Angeles Film Critics Association voted Raging Bull the best film of 1980, and De Niro best actor. The National Board of Review also voted De Niro best actor and Pesci best supporting actor. The Berlin International Film Festival chose Raging Bull to open the festival in 1981.[44]

The 2012 Parajanov-Vartanov Institute Award honored screenwriter Mardik Martin "for the mastery of his pen on iconic American films" Mean Streets and Raging Bull.[54]

Legacy

[edit]By the end of the 1980s, Raging Bull had cemented its reputation as a modern classic. It was voted the best film of the 1980s in numerous critics' polls, and is regularly pointed to as both Scorsese's best film and one of the finest American films ever made.[55] Several prominent critics, among them Roger Ebert, declared the film to be an instant classic and the consummation of Scorsese's earlier promise. Ebert proclaimed it the best film of the 1980s,[56] and one of the ten greatest films of all time.[57] The film has been deemed "culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1990.[58]

Raging Bull was listed by Time magazine as one of the All-TIME 100 Movies.[59] Variety magazine ranked the film number 39 on their list of the 50 greatest movies.[60] Raging Bull is fifth on Entertainment Weekly's list of the 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[61] The film tied with The Bicycle Thieves and Vertigo at number 6 on Sight & Sound's 2002 poll of the greatest movies.[62] When Sight & Sound's directors' and critics' lists from that year are combined, Raging Bull gets the most votes of any movie that has been produced since 1975.[63] In 2002, Film4 held a poll of the 100 Greatest Movies, on which Raging Bull was voted in at number 20.[64] Halliwell's Film Guide, a British film guide, placed Raging Bull seventh in a poll naming their selection for the "Top 1,000 Movies".[65] TV Guide also included the film on their list of the 50 best movies.[66] Movieline magazine included the film on its list of the 100 best movies.[67] Leonard Maltin included Raging Bull on his 100 Must-See Films of the 20th Century list.[68] Video Detective also included the film on its list of the top 100 movies of all time.[69] Roger Ebert named "Robert De Niro's transformation from sleek boxer to paunchy nightclub owner in Raging Bull" as one of the 100 Greatest Movie Moments.[70] The National Society of Film Critics ranked it #75 on their 100 Essential Films list.[71] Rolling Stone magazine ranked it #6 on their list of the 100 Maverick Movies in the Last 100 Years.[72]

A 1997 readers poll conducted by the L.A. Daily News ranked the film #64 on a list of the greatest American movies.[73] The Writers Guild of America named the film as the 76th best screenplay of all time.[74] Raging Bull is #7 on Time Out Film Guide's "Centenary Top 100" list,[75] and it also tied at #16 (with Lawrence of Arabia) on their 1998 readers poll.[76] In 2008, Empire magazine held a poll of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time, taking votes from 10,000 readers, 150 film makers, and 50 film critics in which Raging Bull was placed at number 11.[77] It was also placed on a similar list of 1000 movies by The New York Times.[78] In 2010, Total Film selected the film as one of The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[79] FilmSite.org, a subsidiary of American Movie Classics, placed Raging Bull on their list of the 100 greatest movies.[80] Additionally, Films101.com ranked the film as the 17th best movie of all time in a list of the 10,790 most notable.[81]

In 2012, the Motion Picture Editors Guild listed the film as the best-edited film of all time based on a survey of its membership.[82][83] In the 2012 Sight & Sound polls, it was ranked the 53rd-greatest film ever made in the critics' poll[84] and 12th in the directors' poll.[85] Contemporaries of Scorsese, like Francis Ford Coppola, have included it routinely in their lists for favorite films of all time. In 2015, Raging Bull ranked 29th on BBC's "100 Greatest American Films" list, voted on by film critics from around the world.[86]

American Film Institute recognition

[edit]Soundtrack

[edit]Martin Scorsese decided to assemble a soundtrack made of music that was popular at the time using his personal collection of 78s. With the help of Robbie Robertson, the songs were carefully chosen so they would be the ones that a person would hear on the radio, at the pool or in bars and clubs which reflected the mood of that particular era.[91][92] Some lyrics from songs would also be slipped into some dialogue. The Intermezzo from Cavalleria rusticana by Italian composer Pietro Mascagni would serve as the main theme to Raging Bull after a successful try-out by Scorsese and the editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, over the film's opening titles.[92] Two other Mascagni pieces were used in the film: the Barcarolle from Silvano, and the Intermezzo (Ratcliff's Dream) from Guglielmo Ratcliff.[93] A two-CD soundtrack was released in 2005, long after the film was released, because of earlier difficulties obtaining rights for many of the songs, which Scorsese selected from his childhood memories growing up in New York.

Dispute over sequel

[edit]In 2006, Variety reported that Sunset Pictures was developing a combination sequel and prequel film entitled Raging Bull II: Continuing the Story of Jake LaMotta, chronicling LaMotta's life before and after the events of the original film, as told in the memoir of the same name.[94] Filming began on June 15, 2012, with William Forsythe as the older LaMotta and Mojean Aria as the younger version (before the events of the first film).[95] The film, directed by Martin Guigui, also stars Joe Mantegna, Tom Sizemore, Penelope Ann Miller, Natasha Henstridge, Alicia Witt, Ray Wise, Harry Hamlin, and James Russo as Rocky Graziano.[96][97] In July 2012, MGM, owners of United Artists, filed a lawsuit against LaMotta and the producers of the new film to block it from being released. MGM argued that they had the rights to make any authorized sequel to the original book, tracing their claim back to an agreement LaMotta and co-author Peter Savage made with Chartoff-Winkler, producers of the original film. MGM argued that the defendants were publicly claiming the film to be a sequel to the original film, which they said could "tarnish" the original film's reputation.[98] In August 2012, the suit was settled, with producers of the new film retitling it The Bronx Bull and agreeing not to market it as a sequel to Raging Bull.[99] The film was released in 2016.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Raging Bull". American Film Institute. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ "Raging Bull". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ a b "Raging Bull (1980) – Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ "Alain Delon: French movie actor, who starred in Purple Noon and The Leopard, dies at 88". Sky News. Retrieved April 9, 2025.

- ^ "Martin Scorsese on Visconti's Rocco and His Brothers". www.film-foundation.org. Retrieved April 9, 2025.

- ^ "The four movies that directly inspired Martin Scorsese's 'Raging Bull'". faroutmagazine.co.uk. December 23, 2023. Retrieved April 9, 2025.

- ^ Hemphill, Jim (July 13, 2018). "Rocco and His Brothers, Dietrich and Von Sternberg, and Dragon Inn: Jim Hemphill's Weekend Viewing Recommendations". Filmmaker Magazine. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ "10 Essential Movies to Watch by Marc Eliot 6.Rocco and his Brothers (1960) by Luchino Visconti". Escuela de Cine y Artes Visuales (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ Wiel, Ophélie (July 14, 2015). "Rocco et ses frères". Critikat (in French). Archived from the original on May 7, 2024. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Gamarekian, Barbara (October 19, 1990). "Library of Congress Adds 25 Titles to National Film Registry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 4, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull 2006 p.177.

- ^ "Coley Wallace". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ Biskind, Peter, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, 1999, p. 254.

- ^ Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls 1998, p. 378.

- ^ Biskind, Peter, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, 1998, p. 315.

- ^ a b c d Thompson, David and Christie, Ian, Scorsese on Scorsese, pp. 76/77.

- ^ a b Friedman Lawrence S. The Cinema of Martin Scorsese, 1997, p. 115.

- ^ Phil Villarreal. "Scorsese's 'Raging Bull' is still a knockout", The Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, Arizona), February 11, 2005, p. E1.

- ^ Kelly Jane Torrance. "Martin Scorsese: Telling stories through film", The Washington Times (Washington, D.C.), November 30, 2007, p. E1.

- ^ a b Biskind, Peter, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, 1998, p. 389.

- ^ a b c d Total Film, The 100 greatest films of all time, pp. 180–181.

- ^ a b c Thompson, David and Christie, Ian, Scorsese on Scorsese, p. 80.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 83.

- ^ Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls 1998, p. 379.

- ^ a b Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls pp. 384–385

- ^ a b c Baxter John De Niro A Biography, pp. 186–189.

- ^ Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, p. 390.

- ^ a b c Baxter, John De Niro A Biography, p. 193.

- ^ Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull, p. 65.

- ^ Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Baxter, John De Niro A Biography pp. 196–201

- ^ a b Evans, Mike, The Making of Raging Bull, pp. 65/66.

- ^ Baxter, John, De Niro: A Biography, p. 192.

- ^ a b c d e Thompson and Christie, Scorsese on Scorsese, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Baxter, John, The Making of Raging Bull, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d e f Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls 1999, p.399.

- ^ a b Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull, p. 90.

- ^ Baxter, John De Niro A biography, p. 204.

- ^ "The 75 Best Edited Films Of All Time". IndieWire. Motion Picture Editors Guild. February 2015. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ Eriq Gardner, "Supreme Court Allows 'Raging Bull' Heiress to Sue MGM for Copyright Damages" Archived May 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The Hollywood Reporter, May 19, 2014.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (April 5, 2015). "After Supreme Court, MGM Settles 'Raging Bull' Rights Dispute". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ Spy (November 1988). "The Unstoppables". Spy: The New York Monthly. New York: Sussex Publishers, LLC: 90. ISSN 0890-1759. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull pp. 124–129

- ^ Raging Bull at Box Office Mojo

- ^ "Raging Bull Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on October 13, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ "Raging Bull Movie Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 18, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ "CinemaScore". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. February 20, 1981. p. 2C. Retrieved April 12, 2025.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (October 27, 2011). The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael: A Library of America Special Publication. Library of America. pp. 652–658. ISBN 978-1-59853-171-8.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 14, 1980). "ROBERT DE NIRO IN 'RAGING BULL' (Published 1980)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ "The 53rd Academy Awards (1981) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ "Raging Bull – Academy Awards Database". AMPAS. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- ^ "John Hinckley, Jr". n.d. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Mardik Martin". Parajanov-Vartanov Institute. April 9, 2018. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Walker, John Halliwell's Top 1000, The Ultimate Movie Countdown 2005, p. 561.

- ^ "Ebert's 10 Best Lists: 1967–present". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "Roger Ebert's Ten Greatest Films of All Time". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on January 5, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ Gamarekian, Barbara (October 19, 1990). "Library of Congress Adds 25 Titles to National Film Registry". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ "Time Magazine's All-Time 100 Movies". Time. Internet Archive. February 12, 2005. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ Thompson, Anne. "Lists: 50 Best Movies of All Time, Again". Variety. Archived from the original on September 15, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "Entertainment Weekly's 100 Greatest Movies of All Time". Entertainment Weekly. Published by AMC FilmSite.org. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "Top Ten Poll 2002 – Directors' Poll". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "2002 Sight & Sound Film Survey". cinemacom.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ FilmFour. "Film Four's 100 Greatest Films of All Time". AMC FilmSite.org. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "Halliwell's Top 1000 Movies". Mindjack Film. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "50 Greatest Movies (on TV and Video)". TV Guide. AMC's FilmSite. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ The 100 Best Movies Ever Made. Archived August 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Movieline, published by AMC's Filmsite. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ The 100 Must-See Films of the 20th Century. Archived October 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Leonard Maltin, published by AMC's Filmsite. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ The Top 100 Films of All Time. Archived August 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine AMC's Filmsite. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ The 100 Greatest Movie Moments. Archived August 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine AMC's Filmsite. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ 100 Essential Films. Archived August 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine National Society of Film Critics, published by AMC's Filmsite. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ 100 Maverick Movies in the Last 100 Years. Archived March 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Rolling Stone, published by AMC's Filmsite. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ Greatest American Films. Archived August 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine L.A. Daily News, published by AMC's Filmsite. Published December 3, 1997. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ Writers Guild of America, West. "The 101 Best Screenplays". Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ Top 100 Films. Archived March 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Time Out, published by AMC's Filmsite. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ Top 100 Films. Archived July 18, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Time Out (magazine), published by AMC's Filmsite. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ "Empire's The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire magazine. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made. The New York Times via Internet Archive. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time. Total Film via Internet Archive. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ "Filmsite's 100 Greatest Films". AMC FilmSite.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "The Best Movies of All Time (10,790 Most Notable)". Films101.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ CineMontage's The 75 Best Edited Films. Editors Guild Magazine volume 1, issue 3 via Internet Archive. Published May 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ The 75 Best Edited Films Of All Time Archived March 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Indiewire. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ Christie, Ian, ed. (August 1, 2012). "The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time". Sight & Sound (September 2012). British Film Institute. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Directors' Top 100". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on February 9, 2016.

- ^ "100 Greatest American Films". BBC. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies" Archived June 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills" Archived December 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)" Archived January 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ Thompson, David and Christie, Ian Scorsese on Scorsese p. 83.

- ^ a b Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull p. 88.

- ^ "FAQ 9. What is that nice music in Raging Bull?". mascagni.org. Archived from the original on August 2, 2002. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ Pamela McClintock (August 7, 2006). "Sunset Pictures in shape". Variety. Archived from the original on May 15, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ "'Raging Bull II' is Shooting Now". Slashfilm. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ ""Raging Bull II" headed into production". www.ifc.com. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ "Cannes: Main Street Films Sets U.S. Dates For 'Great Expectations' And 'Bronx Bull'". Deadline. May 20, 2013. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ Patten, D. "MGM Files 'Raging Bull 2' Lawsuit Against Jake LaMotta & Sequel Producers". [1] Deadline Hollywood (July 3, 2012). Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ Patten, Dominic. "MGM Settles 'Raging Bull II' Lawsuit With Movie Name Change". [2] Deadline Hollywood (August 1, 2012). Retrieved on August 2, 2012.

Sources

[edit]- Baxter, John (2006) [2002]. De Niro: A Biography. London: HarperCollins Entertainment. ISBN 0-00-653230-6. OCLC 53460849.

- Biskind, Peter (1998). Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80996-6.

- Evans, Mike (2006). The Making of Raging Bull. London: Unanimous Ltd. ISBN 1-903318-83-1.

- Scorsese, Martin (1996). Thompson, Christie; David, Ian (eds.). Scorsese on Scorsese. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-17827-8. OCLC 35599754 – via Internet Archive.

- Wilson, Michael (2011). Scorsese On Scorsese. Cahiers du Cinéma. ISBN 978-2-86642-702-3.

External links

[edit]- Bernard, Jami (2002). "Raging Bull" (PDF). The A List: The National Society of Film Critics' 100 Essential Films.

- Raging Bull at IMDb

- Raging Bull at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Raging Bull at the TCM Movie Database

- Raging Bull at FilmSite.org

- Raging Bull at Box Office Mojo

- Raging Bull at Rotten Tomatoes

- Raging Bull at Metacritic

- Raging Bull: American Minotaur an essay by Robin Robertson at The Criterion Collection

- Raging Bull: Never Got Me Down an essay by Glenn Kenny at The Criterion Collection

- Raging Bull essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 768–770.

Raging Bull

View on GrokipediaSynopsis

Plot

The film Raging Bull opens in 1964 at the Barbizon Plaza Hotel in New York City, where Jake LaMotta, now a washed-up nightclub performer, rehearses a monologue in his dressing room, shadowboxing and reflecting on his life with a mix of bravado and regret. This framing device sets the stage for flashbacks that chronicle his turbulent career and personal life from the 1940s to the 1950s, returning to 1964 at the conclusion.[6] In 1941, LaMotta, an undefeated middleweight boxer from the Bronx, fights Jimmy Reeves in Cleveland but loses by unanimous decision in a bout fixed by the Mafia, sparking a riot among the crowd. Back home, his volatile temper erupts during an argument with his first wife, Irma, over a poorly cooked steak, leading him to smash the kitchen and later flush her head in the toilet. LaMotta spars with his brother Joey, who manages his career, and expresses insecurities about his physique, insisting he needs to toughen his "girl's hands" to compete against heavyweights. He encounters mob lieutenant Salvy Batts, who urges him to ally with local Mafia boss Tommy Como for better opportunities, but LaMotta rebuffs the overtures.[7][6] LaMotta's obsession with success intensifies as he trains rigorously at Gleason's Gym. At a public swimming pool, he spots 15-year-old Vickie, a beautiful blonde, and begins pursuing her despite his marriage to Irma. Their courtship includes awkward dates like miniature golf and visits to his family's apartment, culminating in a physical relationship. LaMotta divorces Irma and marries Vickie, settling in the Bronx and starting a family. Meanwhile, his career progresses with a grueling 1943 victory over Sugar Ray Robinson in a non-title fight, where he absorbs punishing blows but prevails on points.[6][4] Jealousy increasingly poisons LaMotta's marriage as he grows paranoid about Vickie's interactions with other men, particularly Salvy and his circle. At a church dance, he watches her suspiciously from afar. In 1947, after Vickie compliments boxer Tony Janiro's looks, LaMotta savagely beats him in the ring to prove his dominance. That year, under mob pressure from Tommy Como, LaMotta throws a fight against Billy Fox, taking a blatant dive that results in a suspension from boxing. Despite these setbacks, he rebounds and captures the middleweight world championship in 1949 by defeating Marcel Cerdan via technical knockout in the 10th round.[6][7] LaMotta's paranoia escalates post-title win; he accuses Vickie of infidelity and brutally assaults his brother Joey, mistakenly believing they are having an affair, which strains their relationship irreparably. Domestic violence becomes rampant: LaMotta slaps and chokes Vickie during heated arguments, once smashing a bottle over her head in a fit of rage. In 1951, he loses the title in a ferocious rematch against Sugar Ray Robinson at Chicago Stadium, enduring a barrage of punches including the infamous "St. Valentine's Day Massacre" uppercut that ends the fight in the 13th round, leaving him bloodied and defeated.[6][4] LaMotta's life spirals after retirement in 1956. He opens a nightclub in Florida, where he promotes underage boxing matches, leading to his arrest and imprisonment for pandering and promoting a minor to prostitution. In jail, overcome by despair, he repeatedly punches a concrete wall until his fists bleed, sobbing "Why? Why? Why? Why?!" Vickie divorces him and takes their children, and he pawns his championship belt for cash. Released in 1958, an overweight LaMotta attempts reconciliation with Joey, who rebuffs him, and marries a new woman named Emma.[6][4] The film returns to 1964, where LaMotta, now performing as a stand-up comedian and emcee at a seedy nightclub, delivers a poignant monologue echoing the "I coulda been a contender" speech from On the Waterfront, lamenting his squandered potential and declaring himself "the boss" in a hollow attempt at self-assurance. The narrative draws from LaMotta's 1970 autobiography Raging Bull: My Story, co-written with Joseph Carter and Peter Savage.[6][7]Cast

Robert De Niro portrays Jake LaMotta, the real-life middleweight boxing champion known as the "Bronx Bull," whose tumultuous career and personal life form the film's core.[8] Cathy Moriarty plays Vickie LaMotta, Jake's second wife and a central figure in his domestic life.[8] Joe Pesci depicts Joey LaMotta, Jake's brother who serves as his manager and confidant.[8] Supporting roles include Frank Vincent as Salvy Batts, a low-level mobster and associate of the LaMotta brothers, and Nicholas Colasanto as Tommy Como, a local nightclub owner and boxing promoter with ties to organized crime.[8] The film casts various actors as LaMotta's real-life opponents, highlighting key bouts from his professional record.| Actor | Role | Real-Life Counterpart and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Johnny Barnes | Sugar Ray Robinson (first fight) | Portrays the legendary welterweight/middleweight champion in LaMotta's 1942 debut loss to him; additional uncredited performers depict Robinson in their five subsequent encounters.[9][8] |

| Kevin Mahon | Tony Janiro | The welterweight contender LaMotta faces in 1947, known for his good looks.[9] |

| Eddie Mustafa Muhammad | Billy Fox | The light heavyweight against whom LaMotta competes in 1947.[9] |

| Floyd Anderson | Jimmy Reeves | The opponent in LaMotta's 1941 fight.[9] |

| Louis Raftis | Marcel Cerdan | The French middleweight world champion LaMotta defeats in 1949 to win the title.[9] |

| Johnny Turner | Laurent Dauthuille | The French middleweight LaMotta knocks out in 1950.[9] |

Production

Development

Following the commercial and critical disappointment of New York, New York in 1977, Martin Scorsese became interested in adapting Jake LaMotta's life story as a potential follow-up project, viewing it as an opportunity to explore themes of self-destruction and redemption that resonated with his own struggles.[10] Producers Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff, who had previously collaborated with Scorsese on films like New York, New York, took on the project after Robert De Niro shared LaMotta's autobiography with them during the 1977 production, securing the rights from Dino De Laurentiis and pushing for Scorsese to direct despite his initial reluctance toward a boxing subject.[11] The film's foundation was LaMotta's 1970 autobiography Raging Bull: My Story, co-written with Peter Savage, which detailed the middleweight champion's turbulent career and personal life from 1949 to 1951; LaMotta provided consultations to De Niro and the team, ultimately approving the project in 1978 after reviewing early concepts.[10][12] Pre-production faced significant delays due to Scorsese's severe health crisis in September 1978, when an asthma attack exacerbated by heavy cocaine use led to a near-fatal collapse and hospitalization after the Telluride Film Festival, where he was treated for internal bleeding and weighed just 109 pounds, prompting a period of recovery that postponed the start of work.[11][13] By 1979, as the project gained momentum with United Artists' approval—facilitated by the success of Winkler and Chartoff's Rocky II—Scorsese decided to shoot in black-and-white to evoke the gritty authenticity of classic boxing films and distance the narrative from contemporary color aesthetics.[11][12]Screenplay

The screenplay for Raging Bull was initially drafted by Paul Schrader in 1978, drawing from Jake LaMotta's 1970 autobiography Raging Bull: My Story as the base material.[12] Schrader's version began mid-story without extensive backstory, opening with LaMotta yelling at his wife over a steak dinner and including a violent domestic scene that was later toned down during revisions.[12] This draft established a raw, intense tone but required significant restructuring to better capture LaMotta's complex psyche. Subsequent revisions were handled by Mardik Martin, who had contributed early chronological drafts, alongside director Martin Scorsese.[14] Key changes included the adoption of a non-linear structure to reflect LaMotta's fragmented emotional state and the addition of voiceover narration to provide introspective insights into his mindset.[12] These elements shifted the focus from a straightforward boxing biography to a deeper exploration of psychological decline, prioritizing LaMotta's jealousy, rage, and self-destructive tendencies over his athletic victories. To streamline the narrative, the script compressed LaMotta's extensive boxing career—spanning fights from 1941 to 1954—into select pivotal sequences that highlighted thematic turning points rather than exhaustive match details.[12] Extraneous subplots, such as extensive mob dealings, were toned down to avoid diluting the personal drama.[12] Scorsese and De Niro further refined the script during a 1979 writing retreat on St. Martin, incorporating direct input from LaMotta himself to ensure authenticity in portraying his primal emotions and path to redemption.[12] The final draft, completed that year, solidified these adaptations into a cohesive, character-driven story credited to Schrader and Martin, with uncredited contributions from Scorsese.[14]Casting

The casting of Raging Bull was marked by Robert De Niro's determination to secure Martin Scorsese as director, stemming from their prior collaborations on films like Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976). After Scorsese suffered a collapse from drug abuse in 1978 and was hospitalized, De Niro visited him with the screenplay in hand, delivering what Scorsese later described as a "Come to Jesus" plea to take on the project, emphasizing that no one else could capture the story's essence. De Niro's persistence paid off, as Scorsese agreed despite initial reluctance, viewing the film as a potential career-ender given his personal struggles.[12] For the role of Vickie LaMotta, Cathy Moriarty was discovered at age 17 through a photograph from a disco beauty contest in Mount Vernon, New York, spotted by Joe Pesci and Frank Vincent in 1978. The image caught the attention of casting director Cis Corman, who arranged a screen test; producers Irwin Winkler and Scorsese approved her for her natural, guileless presence that fit the character's vulnerability. Joe Pesci, meanwhile, was cast as Joey LaMotta after Scorsese recalled their earlier meeting during a comedy routine Pesci performed with Vincent, appreciating Pesci's excitable energy for the brother's loyal dynamic.[12] Supporting roles emphasized authenticity, with Frank Vincent selected for the mobster Salvy Batts due to his real-life familiarity with New York underworld figures from his comedy background, adding grit to the scenes. Nicholas Colasanto was chosen as the mob boss Tommy Como, leveraging his prior experience in tough-guy parts from films like Fat City (1972), marking his final feature role before his death in 1985. To heighten realism in the ring, Scorsese cast actual professional boxers and boxing personnel as opponents, referees, cornermen, and announcers, ensuring the fights felt genuine rather than staged.[12][15] Preparations for the cast were rigorous, particularly for De Niro, who trained extensively with the real Jake LaMotta for nearly a year, sparring over 1,000 rounds and even participating in three amateur boxing matches in Brooklyn, winning two to master LaMotta's unorthodox style. To portray the character's later decline, De Niro gained approximately 70 pounds over four months in Italy and France, reaching 215 pounds by eating lavish meals at top restaurants, a transformation that alarmed Scorsese and raised health concerns but was essential for visual authenticity.[12]Principal photography

Principal photography for Raging Bull commenced in April 1979 and continued through December, with the production primarily based in Los Angeles, California, where studios and sets stood in for 1940s New York City. Exteriors and select interiors were filmed on location in New York, including authentic gyms like the Gramercy Gym at 116 East 14th Street and the Tony Dapolito Recreation Center in Greenwich Village, as well as boxing rings at venues such as the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles to replicate period fight scenes.[16][17] The film's fight sequences utilized innovative slow-motion cinematography, directed by Michael Chapman, to emphasize the balletic yet brutal choreography of the boxing matches, often capturing the physical toll in stylized detail. Outside the ring, non-boxing scenes incorporated improvised dialogue to heighten realism, particularly in tense family confrontations, while Robert De Niro ad-libbed much of his physical performance as Jake LaMotta, including spontaneous movements that added raw intensity to his portrayal. For instance, during an improvised brawl scene, De Niro accidentally broke co-star Joe Pesci's rib, underscoring the commitment to unscripted authenticity.[18][19][20] Production faced significant challenges, including budget overruns that escalated costs to $18 million, straining United Artists' resources amid the studio's financial difficulties. Martin Scorsese's demanding directing approach, which he later described as "kamikaze filmmaking," intensely pushed the actors through repeated takes and emotional extremes to extract visceral performances, contributing to the on-set tension.[21][22]Post-production

The post-production of Raging Bull was overseen by editor Thelma Schoonmaker, who refined the footage over six months, far exceeding the initial seven-week allotment.[23] Schoonmaker focused on rhythmic synchronization between the fight punches and sound, collaborating with sound editor Frank Warner to create distinct audio effects for each impact, such as layered animal roars and unconventional booms to amplify the visceral intensity.[24] The final assembly trimmed the film to a runtime of 129 minutes, emphasizing tight pacing while preserving Scorsese's improvisational energy in non-fight scenes.[1] Visual decisions enhanced the film's gritty realism, with minimal effects limited primarily to slow-motion sequences in the boxing matches to convey Jake LaMotta's obsessive mindset and distort time during key moments.[23] For the home movie flashbacks, footage was optically degraded into sepia tones and desaturated hues to simulate aged, personal recollections, while the overall black-and-white aesthetic drew from high-contrast 1940s press photography.[24] To achieve a grainy texture, Scorsese manually scratched the negatives with a wire hanger in the cutting room, rejecting smoother prints for a raw, documentary-like quality.[25] Final touches included recording Robert De Niro's voiceovers as LaMotta's introspective narration, added to provide psychological depth during fights and personal reflections, alongside precise color timing to balance the sepia inserts against the monochrome body of the film for its November 1980 release.[1]Copyright litigation

Prior to the film's production, Jake LaMotta and Frank Petrella assigned their rights in the screenplay and autobiography—key source materials for Raging Bull—to Chartoff-Winkler Productions in 1976, including renewal rights under the Copyright Act.[26] This assignment facilitated the film's development without reported pre-release litigation, though LaMotta served as a technical consultant during principal photography to ensure authenticity in depicting his boxing career.[27] The primary copyright litigation arose post-release when Paula Petrella, daughter of co-author Frank Petrella (who died in 1981), renewed the copyright to her father's 1963 screenplay in 1991 and sued Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) in 2009 for infringement. She alleged that MGM's production, distribution, and ongoing exploitation of the 1980 film—including home video releases and licensing—violated her exclusive rights, as the 1976 assignment did not fully encompass the renewed copyright.[28] The U.S. District Court for the Central District of California granted summary judgment to MGM in 2011, citing the equitable doctrine of laches due to Paula Petrella's 18-year delay in suing after renewing the copyright; the Ninth Circuit affirmed in 2012, emphasizing prejudice to MGM from continued investments in the film.[29] In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Ninth Circuit in a 6-3 decision, holding that laches cannot bar claims for damages accruing within the three-year statute of limitations under the Copyright Act, though it noted equitable relief might still apply in extraordinary cases.[26] The case returned to the district court, where MGM argued the film did not substantially infringe the original screenplay and that any similarities stemmed from independent creation based on LaMotta's life story.[30] In April 2015, the parties settled the dispute confidentially, resolving all claims related to MGM's use and distribution of Raging Bull without admission of liability.[30] In the 1990s, minor challenges emerged regarding sequel rights tied to LaMotta's autobiography, stemming from ambiguities in the original 1976 assignment, though these did not escalate to full litigation at the time.[31]Themes and analysis

Cinematic style

The black-and-white cinematography of Raging Bull, led by Michael Chapman, relies on high-contrast chiaroscuro lighting and deep shadows to amplify emotional intensity and visceral impact across the film's scenes.[32] Shot on black-and-white negative stock, this technique was selected to achieve a timeless aesthetic that resists the fading associated with color film over time.[22] Scorsese chose black and white after initial color tests, which highlighted issues like the anachronistic vibrancy of red boxing gloves against the 1940s period, instead evoking the gritty realism of vintage newsreels and tabloid photography by Weegee.[22] The fight sequences stand out for their operatic choreography, synchronized with dramatic music cues from Pietro Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana, which elevate the bouts to stylized, aria-like spectacles.[22] Scorsese employs slow-motion footage—often shot at 48 frames per second and doubled for emphasis—and wide-angle shots to underscore the brutality, distorting space and prolonging the agony of impacts for heightened sensory effect.[33] These elements, paired with Chapman's stark contrasts, transform the ring into a stark arena of raw physicality.[32] Scorsese's directorial techniques favor handheld camerawork to foster intimacy, immersing the audience in the immediacy of the action through unsteady, close-quarters perspectives.[33] Recurring visual motifs, such as swirling cigarette smoke that diffuses light and atmosphere, and religious imagery—including ritualistic applications of Vaseline resembling benedictions—contribute to the film's textured, immersive style.[22] The editing rhythms crafted by Thelma Schoonmaker sync tightly with these choices, enhancing the overall kinetic flow.[22]Central themes

Raging Bull explores the theme of jealousy and self-destruction through the character of Jake LaMotta, whose paranoia about his wife Vickie's fidelity erodes his personal relationships and leads to cycles of violence both in and out of the boxing ring. LaMotta's obsessive suspicions, often triggered by innocuous social interactions, manifest in physical abuse toward Vickie and his brother Joey, blurring the lines between his professional aggression and domestic turmoil. This self-destructive behavior stems from deep-seated insecurities, resulting in isolation and the breakdown of his support network, as LaMotta's rage turns inward, punishing himself through masochistic fights and personal failures.[34][35][36] The film critiques toxic masculinity by portraying LaMotta's adherence to rigid ideals of manhood—dominance, honor, and control—as ultimately destructive, yet it also hints at redemption through spiritual reflection. LaMotta embodies hyper-masculine traits tied to violence and emotional repression, viewing vulnerability as weakness, which exacerbates his abusive tendencies and moral isolation. The film's closing title card quotes John 9:25 from the Bible—"One thing I do know, that though I was blind, now I see"—suggesting a moment of awakening and drawing parallels to Catholic notions of suffering and atonement, offering a tentative path toward self-forgiveness amid his life's wreckage. This arc, inspired by LaMotta's autobiography, underscores the film's examination of manhood's burdens without full resolution.[34][37][35][38] Power and corruption permeate Raging Bull via the mob's influence on boxing, forcing LaMotta into moral compromises that highlight the sport's underbelly and his internal conflict. To secure title shots, LaMotta reluctantly throws a fight against Billy Fox, a decision that haunts him and symbolizes broader ethical decay in pursuit of success. His resistance to full mob allegiance leads to professional setbacks and personal ruin, illustrating how external corruption amplifies his self-inflicted wounds within the Italian American underclass.[35][34]Release and reception

Box office

Raging Bull was produced on a budget of $18 million.[3] The film premiered in New York City on November 14, 1980, before a wide release, and ultimately grossed $23.4 million domestically against that cost.[39] Worldwide earnings reached approximately $23.4 million, equivalent to $80–100 million when adjusted for inflation.[3] Its initial box office performance was modest and built slowly, opening to just $128,590 in its first weekend amid competition from color blockbusters of the era; the black-and-white cinematography likely contributed to the muted start in a market favoring vibrant visuals.[39] However, the film demonstrated strong legs, running for months with earnings 36 times its peak weekend, as visibility surged following its Academy Award nominations in early 1981.[3] In comparison to 1980 contemporaries, Raging Bull underperformed relative to hits like Ordinary People, which earned $54.8 million domestically on a $6.2 million budget.[40] Despite the theatrical shortfall, the film recouped costs through $10.1 million in studio rentals and later found substantial long-tail success via home video rentals.[41]Critical response

Upon its release in 1980, Raging Bull garnered widespread critical acclaim, particularly for Robert De Niro's transformative portrayal of Jake LaMotta, which many reviewers hailed as one of the actor's career peaks. Roger Ebert awarded the film four out of four stars, praising it as "the most painful and heartrending portrait of jealousy in the cinema" and emphasizing its raw emotional depth in depicting LaMotta's self-destructive rage.[4] Pauline Kael, in her New Yorker review, lauded Scorsese's direction and the film's gritty visual rhythm, though she noted that the narrative's intensity sometimes overshadowed its broader biographical scope.[42] While the boxing sequences were universally admired for their visceral energy, some contemporary critics observed that the film's pacing outside the ring felt deliberately measured, contributing to its overall somber tone but occasionally testing viewer patience.[43] In retrospective assessments, Raging Bull has solidified its status as one of Martin Scorsese's masterpieces, celebrated for its unflinching exploration of raw human emotion and technical innovation. It holds a 92% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 151 reviews, with the critics' consensus describing it as "arguably Martin Scorsese's and Robert De Niro's finest film," a searing yet painful work centered on an unsympathetic antihero.[44] Ebert later included it in his Great Movies collection, reaffirming its status as a profound tragedy akin to Othello.[4] Publications like The New Yorker have revisited it as a pinnacle of Scorsese's style, highlighting its blend of violence and introspection that continues to resonate decades later.[45] Minor criticisms have persisted over the years, with some reviewers pointing to misogynistic undertones in the portrayal of female characters, who often serve as outlets for LaMotta's paranoia and abuse, though defenders argue this faithfully reflects the subject's flaws without endorsement.[46] Additionally, the film's 129-minute length has been cited by a few as a potential barrier, amplifying its emotional weight but risking alienation for audiences seeking faster-paced entertainment.[44]Accolades

Raging Bull garnered significant recognition from major awards bodies following its release, particularly in the 1980-1981 awards season. At the 53rd Academy Awards in 1981, the film received eight nominations, establishing it as a leading contender. It won two Oscars: Best Actor for Robert De Niro's transformative portrayal of Jake LaMotta, and Best Film Editing for Thelma Schoonmaker's innovative work that captured the intensity of the boxing sequences.[47] The nominations also included Best Picture (producers Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff), Best Director for Martin Scorsese, Best Supporting Actor for Joe Pesci, Best Supporting Actress for Cathy Moriarty, Best Writing (Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium) for Mardik Martin and Paul Schrader, and Best Cinematography for Michael Chapman's stark black-and-white visuals.[47] Beyond the Oscars, De Niro's performance earned him the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama at the 38th Golden Globe Awards in 1981, highlighting the film's emotional depth.[48] The British Academy Film Awards (BAFTA) in 1982 recognized Raging Bull with nominations in categories such as Best Film, Best Actor (De Niro), and Best Supporting Actress (Moriarty), and a win for Best Editing (Schoonmaker). Additionally, the National Board of Review included the film among its Top Ten Films of 1980, praising its raw depiction of personal turmoil.[49] These accolades, totaling eight Oscar nods and key wins from prestigious organizations, underscored Raging Bull's critical prestige and its status as an awards-season powerhouse despite its unconventional style.[47]Legacy

Institutional recognition

Raging Bull has received significant recognition from the American Film Institute (AFI) through its various "100 Years..." lists. In the inaugural 1998 edition of AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies, the film was ranked #24 among the greatest American films of all time.[50] It climbed to #4 in the 2007 10th Anniversary Edition of the same list, reflecting its enduring critical acclaim.[51] Additionally, in AFI's 2008 10 Top 10 list, Raging Bull was named the #1 sports film, ahead of classics like Rocky and The Pride of the Yankees.[52] The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 1990, one of the first 25 titles inducted, honoring its cultural, historic, and aesthetic significance to American cinema.[53] This archival honor underscores the film's lasting impact as a landmark in biographical and sports drama genres. Raging Bull has also appeared prominently in international rankings. It ranked #11 on Empire magazine's poll of the 500 Greatest Movies of All Time in 2008, compiled from votes by readers, filmmakers, and critics.[54] The film has been consistently included in the British Film Institute's decennial Sight & Sound poll of the greatest films; for instance, it placed #53 in the 2012 critics' poll and #12 in the directors' poll, while ranking #25 in the 2022 directors' poll.[55]Cultural impact

Raging Bull has profoundly influenced the boxing biopic genre, establishing a template for raw, unflinching portrayals of athletes' personal turmoil that subsequent films emulated. For instance, Ron Howard's Cinderella Man (2005), which chronicles boxer James J. Braddock's comeback during the Great Depression, draws on Raging Bull's emphasis on the psychological toll of the sport, blending visceral fight sequences with domestic strife to humanize its protagonist.[56] The film's stylistic innovations, such as its black-and-white cinematography and innovative sound design for punches, became benchmarks for authenticity in later boxing narratives.[57] The collaboration between director Martin Scorsese and actor Robert De Niro in Raging Bull marked a high point in their partnership, paving the way for subsequent works that explored similar themes of ambition and self-destruction. This dynamic directly informed their 1990 film Goodfellas, where De Niro's portrayal of Jimmy Conway echoes the intense, internalized rage of Jake LaMotta, refining Scorsese's approach to character-driven crime dramas with heightened emotional depth.[58] Their work on Raging Bull solidified a creative synergy that produced multiple masterpieces, influencing the gangster genre's evolution toward more introspective storytelling.[59] In the broader societal context, Raging Bull has resonated as a stark examination of toxic masculinity, particularly in discussions amplified by the #MeToo movement, where its depiction of Jake LaMotta's abusive behavior toward women prompted reevaluations of unchecked male aggression in cinema. De Niro himself reflected on the film's portrayal of such dynamics amid the cultural reckoning with #MeToo, noting how LaMotta's rage exemplifies the destructive undercurrents of traditional manhood.[60] The 40th anniversary retrospectives in 2020 further highlighted this, with critics framing the movie as a prescient critique of patriarchal violence that remains relevant in contemporary gender discourse.[61] Recent events underscore the film's ongoing cultural vitality, including a special screening at the 2024 De Niro Con during the Tribeca Festival, where Raging Bull was presented alongside other De Niro classics to celebrate his career and the movie's enduring legacy.[62] In 2025, marking the film's 45th anniversary, theaters hosted re-releases of a new 4K restoration, accompanied by podcasts dissecting its themes and production, such as episodes on That 80s Show SA that revisited its narrative impact.[63] Iconic quotes like "You never got out of the cage" continue to permeate pop culture, referenced in media analyses of personal redemption and invoked in discussions of mental health in sports.[64]Media

Soundtrack

The soundtrack of Raging Bull features a mix of pre-existing classical compositions and period-appropriate popular songs from the 1940s, curated to underscore the film's emotional depth and historical setting, with production overseen by Robbie Robertson, who also contributed original instrumental cues such as "Webster Hall," "A New Kind of Love," and "At Last" for transitional and reflective moments.[65][66] Central to the score are selections from Italian composer Pietro Mascagni's operas, used for emotional underscoring in key sequences; the "Intermezzo" from Cavalleria Rusticana (1890) bookends the film in the opening and closing credits, evoking tragedy and jealousy that parallel Jake LaMotta's downfall, while the "Barcarolle" from Silvano (1895) accompanies a montage of family home movies, adding a layer of poignant reflection after a fight loss.[67] Other Mascagni pieces, including the "Intermezzo" from Guglielmo Ratcliff (1895), appear in three instances: transitioning from a victory over Tony Janiro to training amid jealousy, contrasting violence in a beating scene with soft orchestration, and building tension during the Marcel Cerdan fight to a triumphant chord that foreshadows later defeat.[67] These classical elements, performed by the Orchestra of Bologna Municipal Theatre under Arturo Basile, were selected over contemporary pop tracks for their ambiguous emotional resonance, enhancing the film's operatic tone.[67] Popular songs provide period authenticity and ironic contrast in non-fight scenes, such as Ella Fitzgerald and The Ink Spots' "Cow-Cow Boogie (Coss-Coss-Coss Mr. Lindy Goombah)" during casual social moments, or Artie Shaw's "Frenesi" in nightclub settings, highlighting LaMotta's volatile personal life against upbeat 1940s swing and jazz.[68][69] Tracks like Bing Crosby's "Just One More Chance" and Harry James' "Two O'Clock Jump" (featuring Frank Sinatra) evoke the era's optimism, juxtaposed with the protagonist's rage for dramatic irony.[65] The music is tightly integrated with the visuals, particularly in fight scenes where rhythms from Mascagni's compositions synchronize with punch impacts and slow-motion choreography to heighten visceral intensity and psychological disorientation, as seen in the Cerdan bout where orchestral swells align with escalating action.[67] No full official album was released at the film's 1980 debut; the complete soundtrack, compiling 37 tracks across two discs, first appeared in 2005 from Capitol Records, restoring the diverse selections for broader appreciation.[66][70]Home media

The film was first released on home video in 1981 on VHS by United Artists.[](https://movies.fandom.com/wiki/Raging_Bull/Home_media) In 1990, the Criterion Collection issued a three-disc CAV LaserDisc set featuring the film in its original aspect ratio, along with audio commentary tracks by director Martin Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, as well as supplemental interviews and essays on the production. [](http://www.dvdbeaver.com/film10/blu-ray_review_153/raging_bull_4K_UHD.htm)

High-definition upgrades began with MGM's Blu-ray release in 2009, sourced from a high-definition master, which included the 30th Anniversary Edition in 2011 with restored visuals and additional featurettes on the film's making. [](http://www.dvdbeaver.com/film10/blu-ray_review_153/raging_bull_4K_UHD.htm) [](https://www.blu-ray.com/movies/Raging-Bull-Blu-ray/17762/) The Criterion Collection's definitive edition arrived in 2022 as a 4K UHD Blu-ray, featuring a new 4K digital master supervised by Scorsese from the original camera negative, enhanced with Dolby Vision HDR and a newly created Dolby Atmos audio mix for immersive sound design. [](https://www.criterion.com/films/29158-raging-bull) [](https://www.blu-ray.com/movies/Raging-Bull-4K-Blu-ray/315389/) This edition also incorporated extensive supplements, including restored audio commentary and a documentary on the film's legacy.