Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Flip-flop (electronics)

View on Wikipedia

In electronics, flip-flops and latches are circuits that have two stable states that can store state information – a bistable multivibrator. The circuit can be made to change state by signals applied to one or more control inputs and will output its state (often along with its logical complement too). It is the basic storage element in sequential logic. Flip-flops and latches are fundamental building blocks of digital electronics systems used in computers, communications, and many other types of systems.

Flip-flops and latches are used as data storage elements to store a single bit (binary digit) of data; one of its two states represents a "one" and the other represents a "zero". Such data storage can be used for storage of state, and such a circuit is described as sequential logic in electronics. When used in a finite-state machine, the output and next state depend not only on its current input, but also on its current state (and hence, previous inputs). It can also be used for counting of pulses, and for synchronizing variably-timed input signals to some reference timing signal.

The term flip-flop has historically referred generically to both level-triggered (asynchronous, transparent, or opaque) and edge-triggered (synchronous, or clocked) circuits that store a single bit of data using gates.[1][2] Modern authors reserve the term flip-flop exclusively for edge-triggered storage elements and latches for level-triggered ones.[3][4] The terms "edge-triggered", and "level-triggered" may be used to avoid ambiguity.[5]

When a level-triggered latch is enabled it becomes transparent, but an edge-triggered flip-flop's output only changes on a clock edge (either positive going or negative going).

Different types of flip-flops and latches are available as integrated circuits, usually with multiple elements per chip. For example, 74HC75 is a quadruple transparent latch in the 7400 series.

History

[edit]

The first electronic latch was invented in 1918 by the British physicists William Eccles and F. W. Jordan.[6][7] It was initially called the Eccles–Jordan trigger circuit and consisted of two active elements (vacuum tubes).[8] The design was used in the 1943 British Colossus codebreaking computer[9] and such circuits and their transistorized versions were common in computers even after the introduction of integrated circuits, though latches and flip-flops made from logic gates are also common now.[10][11] Early latches were known variously as trigger circuits or multivibrators.

According to P. L. Lindley, an engineer at the US Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the flip-flop types detailed below (SR, D, T, JK) were first discussed in a 1954 UCLA course on computer design by Montgomery Phister, and then appeared in his book Logical Design of Digital Computers.[12][13] Lindley was at the time working at Hughes Aircraft under Eldred Nelson, who had coined the term JK for a flip-flop which changed states when both inputs were on (a logical "one"). The other names were coined by Phister. They differ slightly from some of the definitions given below. Lindley explains that he heard the story of the JK flip-flop from Eldred Nelson, who is responsible for coining the term while working at Hughes Aircraft. Flip-flops in use at Hughes at the time were all of the type that came to be known as J-K. In designing a logical system, Nelson assigned letters to flip-flop inputs as follows: #1: A & B, #2: C & D, #3: E & F, #4: G & H, #5: J & K. Nelson used the notations "j-input" and "k-input" in a patent application filed in 1953.[14]

Implementation

[edit]

Transparent or asynchronous latches can be built around a single pair of cross-coupled inverting elements: vacuum tubes, bipolar transistors, field-effect transistors, inverters, and inverting logic gates have all been used in practical circuits.

Clocked flip-flops are specially designed for synchronous systems; such devices ignore their inputs except at the transition of a dedicated clock signal (known as clocking, pulsing, or strobing). Clocking causes the flip-flop either to change or to retain its output signal based upon the values of the input signals at the transition. Some flip-flops change output on the rising edge of the clock, others on the falling edge.

Since the elementary amplifying stages are inverting, two stages can be connected in succession (as a cascade) to form the needed non-inverting amplifier. In this configuration, each amplifier may be considered as an active inverting feedback network for the other inverting amplifier. Thus the two stages are connected in a non-inverting loop although the circuit diagram is usually drawn as a symmetric cross-coupled pair (both the drawings are initially introduced in the Eccles–Jordan patent).

Types

[edit]Flip-flops and latches can be divided into common types: SR ("set-reset"), D ("data"), T ("toggle"), and JK (see History section above). The behavior of a particular type can be described by the characteristic equation that derives the "next" output (Qnext) in terms of the input signal(s) and/or the current output, .

Asynchronous set-reset latches

[edit]When using static gates as building blocks, the most fundamental latch is the asynchronous Set-Reset (SR) latch.

Its two inputs S and R can set the internal state to 1 using the combination S=1 and R=0, and can reset the internal state to 0 using the combination S=0 and R=1.[note 1]

The SR latch can be constructed from a pair of cross-coupled NOR or NAND logic gates. The stored bit is present on the output marked Q.

It is convenient to think of NAND, NOR, AND and OR as controlled operations, where one input is chosen as the control input set and the other bit as the input to be processed depending on the state of the control. Then, all of these gates have one control value that ignores the input (x) and outputs a constant value, while the other control value lets the input pass (maybe complemented):

Essentially, they can all be used as switches that either set a specific value or let an input value pass.

SR NOR latch

[edit]

- S = 1, R = 0: Set

- S = 0, R = 0: Hold

- S = 0, R = 1: Reset

- S = 1, R = 1: Not allowed

The SR NOR latch consists of two parallel NOR gates where the output of each NOR is also fanned out into one input of the other NOR, as shown in the figure. We call these output-to-input connections feedback inputs, or simply feedbacks. The remaining inputs we will use as control inputs as explained above. Notice that at this point, because everything is symmetric, it does not matter to which inputs the outputs are connected. We now break the symmetry by choosing which of the remaining control inputs will be our set and reset and we can call "set NOR" the NOR gate with the set control and "reset NOR" the NOR with the reset control; in the figures the set NOR is the bottom one and the reset NOR is the top one. The output of the reset NOR will be our stored bit Q, while we will see that the output of the set NOR stores its complement Q.

To derive the behavior of the SR NOR latch, consider S and R as control inputs and remember that, from the equations above, set and reset NOR with control 1 will fix their outputs to 0, while set and reset NOR with control 0 will act as a NOT gate. With this it is now possible to derive the behavior of the SR latch as simple conditions (instead of, for example, assigning values to each line see how they propagate):

- While the R and S are both zero, both R NOR and S NOR simply impose the feedback being the complement of the output, this is satisfied as long as the outputs are the complement of each other. Thus the outputs Q and Q are maintained in a constant state, whether Q=0 or Q=1.

- If S=1 while R=0, then the set NOR will fix Q=0, while the reset NOR will adapt and set Q=1. Once S is set back to zero the values are maintained as explained above.

- Similarly, if R=1 while S=0, then the reset NOR fixes Q=0 while the set NOR with adapt Q=1. Again the state is maintained if R is set back to 0.

- If R=S=1, the NORs will fix both outputs to 0, which is not a valid state storing complementary values.

SR latch operation[5] Characteristic table Excitation table S R Qnext Action Q Qnext S R 0 0 Q Hold state 0 0 0 X 0 1 0 Reset 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 Set 1 0 0 1 1 1 X Not allowed 1 1 X 0

Note: X means don't care, that is, either 0 or 1 is a valid value.

The R = S = 1 combination is called a restricted combination or a forbidden state because, as both NOR gates then output zeros, it breaks the logical equation Q = not Q. The combination is also inappropriate in circuits where both inputs may go low simultaneously (i.e. a transition from restricted to hold). The output could remain in a metastable state and may eventually lock at either 1 or 0 depending on the propagation time relations between the gates (a race condition).

To overcome the restricted combination, one can add gates to the inputs that would convert (S, R) = (1, 1) to one of the non-restricted combinations. That can be:

- Q = 1 (1, 0) – referred to as an S (dominated)-latch

- Q = 0 (0, 1) – referred to as an R (dominated)-latch

This is done in nearly every programmable logic controller.

- Hold state (0, 0) – referred to as an E-latch

Alternatively, the restricted combination can be made to toggle the output. The result is the JK latch.

The characteristic equation for the SR latch is:

- or [15]

where A + B means (A or B), AB means (A and B)

Another expression is:

- with [16]

SR NAND latch

[edit]

The circuit shown below is a basic NAND latch. The inputs are also generally designated S and R for Set and Reset respectively. Because the NAND inputs must normally be logic 1 to avoid affecting the latching action, the inputs are considered to be inverted in this circuit (or active low).

The circuit uses the same feedback as SR NOR, just replacing NOR gates with NAND gates, to "remember" and retain its logical state even after the controlling input signals have changed. Again, recall that a 1-controlled NAND always outputs 0, while a 0-controlled NAND acts as a NOT gate. When the S and R inputs are both high, feedback maintains the Q outputs to the previous state. When either is zero, they fix their output bits to 0 while to other adapts to the complement. S=R=0 produces the invalid state.

|

|

SR AND-OR latch

[edit]

From a teaching point of view, SR latches drawn as a pair of cross-coupled components (transistors, gates, tubes, etc.) are often hard to understand for beginners. A didactically easier explanation is to draw the latch as a single feedback loop instead of the cross-coupling. The following is an SR latch built with an AND gate with one inverted input and an OR gate. Note that the inverter is not needed for the latch functionality, but rather to make both inputs High-active.

SR AND-OR latch operation S R Action 0 0 No change; random initial 1 0 Q = 1 X 1 Q = 0

Note that the SR AND-OR latch has the benefit that S = 1, R = 1 is well defined. In above version of the SR AND-OR latch it gives priority to the R signal over the S signal. If priority of S over R is needed, this can be achieved by connecting output Q to the output of the OR gate instead of the output of the AND gate.

The SR AND-OR latch is easier to understand, because both gates can be explained in isolation, again with the control view of AND and OR from above. When neither S or R is set, then both the OR gate and the AND gate are in "hold mode", i.e., they let the input through, their output is the input from the feedback loop. When input S = 1, then the OR gate outputs 1, regardless of the other input from the feedback loop ("set mode"). When input R = 1 then the AND gate outputs 0, regardless of the other input from the feedback loop ("reset mode"). And since the AND gate takes the output of the OR gate as input, R has priority over S. Latches drawn as cross-coupled gates may look less intuitive, as the behavior of one gate appears to be intertwined with the other gate. The standard NOR or NAND latches could also be re-drawn with the feedback loop, but in their case the feedback loop does not show the same signal value throughout the whole feedback loop. However, the SR AND-OR latch has the drawback that it would need an extra inverter, if an inverted Q output is needed.

Note that the SR AND-OR latch can be transformed into the SR NOR latch using logic transformations: inverting the output of the OR gate and also the 2nd input of the AND gate and connecting the inverted Q output between these two added inverters; with the AND gate with both inputs inverted being equivalent to a NOR gate according to De Morgan's laws.

JK latch

[edit]The JK latch is much less frequently used than the JK flip-flop. The JK latch follows the following state table:

JK latch truth table J K Qnext Comment 0 0 Q No change 0 1 0 Reset 1 0 1 Set 1 1 Q Toggle

Hence, the JK latch is an SR latch that is made to toggle its output (oscillate between 0 and 1) when passed the input combination of 11.[17] Unlike the JK flip-flop, the 11 input combination for the JK latch is not very useful because there is no clock that directs toggling.[18]

Gated latches and conditional transparency

[edit]Latches are designed to be transparent. That is, input signal changes cause immediate changes in output. Additional logic can be added to a transparent latch to make it non-transparent or opaque when another input (an "enable" input) is not asserted. When several transparent latches follow each other, if they are all transparent at the same time, signals will propagate through them all. However, following a transparent-high latch by a transparent-low latch (or vice-versa) causes the state and output to only change on clock edges, forming what is called a master–slave flip-flop.

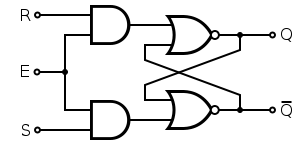

Gated SR latch

[edit]

A gated SR latch can be made by adding a second level of NAND gates to an inverted SR latch. The extra NAND gates further invert the inputs so a SR latch becomes a gated SR latch (a SR latch would transform into a gated SR latch with inverted enable).

Alternatively, a gated SR latch (with non-inverting enable) can be made by adding a second level of AND gates to a SR latch.

With E high (enable true), the signals can pass through the input gates to the encapsulated latch; all signal combinations except for (0, 0) = hold then immediately reproduce on the (Q, Q) output, i.e. the latch is transparent.

With E low (enable false) the latch is closed (opaque) and remains in the state it was left the last time E was high.

A periodic enable input signal may be called a write strobe. When the enable input is a clock signal, the latch is said to be level-sensitive (to the level of the clock signal), as opposed to edge-sensitive like flip-flops below.

|

|

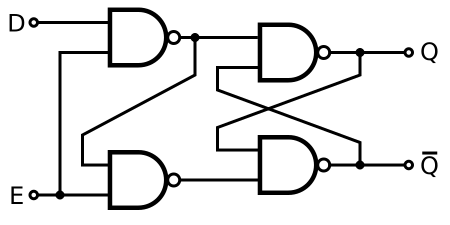

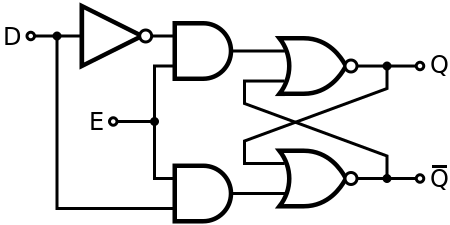

Gated D latch

[edit]This latch exploits the fact that, in the two active input combinations (01 and 10) of a gated SR latch, R is the complement of S. The input NAND stage converts the two D input states (0 and 1) to these two input combinations for the next SR latch by inverting the data input signal. The low state of the enable signal produces the inactive "11" combination. Thus a gated D-latch may be considered as a one-input synchronous SR latch. This configuration prevents application of the restricted input combination. It is also known as transparent latch, data latch, or simply gated latch. It has a data input and an enable signal (sometimes named clock, or control). The word transparent comes from the fact that, when the enable input is on, the signal propagates directly through the circuit, from the input D to the output Q. Gated D-latches are also level-sensitive with respect to the level of the clock or enable signal.

Transparent latches are typically used as I/O ports or in asynchronous systems, or in synchronous two-phase systems (synchronous systems that use a two-phase clock), where two latches operating on different clock phases prevent data transparency as in a master–slave flip-flop.

The truth table below shows that when the enable/clock input is 0, the D input has no effect on the output. When E/C is high, the output equals D.

|

|

-

A gated D latch based on an SR NAND latch

-

A gated D latch based on an SR NOR latch

-

An animated gated D latch. Black and white mean logical '1' and '0', respectively.

- D = 1, E = 1: set

- D = 1, E = 0: hold

- D = 0, E = 0: hold

- D = 0, E = 1: reset

-

A gated D latch in pass transistor logic, similar to the ones in the CD4042 or the CD74HC75 integrated circuits

Earle latch

[edit]The classic gated latch designs have some undesirable characteristics.[19] They require dual-rail logic or an inverter. The input-to-output propagation may take up to three gate delays. The input-to-output propagation is not constant – some outputs take two gate delays while others take three.

Designers looked for alternatives.[20] A successful alternative is the Earle latch. It requires only a single data input, and its output takes a constant two gate delays. In addition, the two gate levels of the Earle latch can, in some cases, be merged with the last two gate levels of the circuits driving the latch because many common computational circuits have an OR layer followed by an AND layer as their last two levels. Merging the latch function can implement the latch with no additional gate delays.[19] The merge is commonly exploited in the design of pipelined computers, and, in fact, was originally developed by John G. Earle to be used in the IBM System/360 Model 91 for that purpose.[21]

The Earle latch is hazard free.[22] If the middle NAND gate is omitted, then one gets the polarity hold latch, which is commonly used because it demands less logic.[22][23] However, it is susceptible to logic hazard. Intentionally skewing the clock signal can avoid the hazard.[23]

-

Earle latch uses complementary enable inputs: enable active low (E_L) and enable active high (E_H)

-

An animated Earle latch. Black and white mean logical '1' and '0', respectively.

- D = 1, E_H = 1: set

- D = 0, E_H = 1: reset

- D = 1, E_H = 0: hold

D flip-flop

[edit]

The D flip-flop is widely used, and known as a "data" flip-flop. The D flip-flop captures the value of the D-input at a definite portion of the clock cycle (such as the rising edge of the clock). That captured value becomes the Q output. At other times, the output Q does not change.[24][25] The D flip-flop can be viewed as a memory cell, a zero-order hold, or a delay line.[26]

Truth table:

Clock D Qnext Rising edge 0 0 Rising edge 1 1 Non-rising X Q

(X denotes a don't care condition, meaning the signal is irrelevant)

Most D-type flip-flops in ICs have the capability to be forced to the set or reset state (which ignores the D and clock inputs), much like an SR flip-flop. Usually, the illegal S = R = 1 condition is resolved in D-type flip-flops. Setting S = R = 0 makes the flip-flop behave as described above. Here is the truth table for the other possible S and R configurations:

Inputs Outputs S R D > Q Q 0 1 X X 0 1 1 0 X X 1 0 1 1 X X 1 1

These flip-flops are very useful, as they form the basis for shift registers, which are an essential part of many electronic devices. The advantage of the D flip-flop over the D-type "transparent latch" is that the signal on the D input pin is captured the moment the flip-flop is clocked, and subsequent changes on the D input will be ignored until the next clock event. An exception is that some flip-flops have a "reset" signal input, which will reset Q (to zero), and may be either asynchronous or synchronous with the clock.

The above circuit shifts the contents of the register to the right, one bit position on each active transition of the clock. The input X is shifted into the leftmost bit position.

Classical positive-edge-triggered D flip-flop

[edit]This circuit[27] consists of two stages implemented by SR NAND latches. The input stage (the two latches on the left) processes the clock and data signals to ensure correct input signals for the output stage (the single latch on the right). If the clock is low, both the output signals of the input stage are high regardless of the data input; the output latch is unaffected and it stores the previous state. When the clock signal changes from low to high, only one of the output voltages (depending on the data signal) goes low and sets/resets the output latch: if D = 0, the lower output becomes low; if D = 1, the upper output becomes low. As long as the clock signal stays high, these input-stage outputs keep their states regardless of the data input and force the output latch to stay in the corresponding state, as the input logical zero (of the output stage) remains active while the clock is high. Any change of the data input while the clock is high will not change the states of the two input-stage latches. Hence the role of the output latch is to store the data only while the clock is low.

The circuit is closely related to the gated D latch as both the circuits convert the two D input states (0 and 1) to two input combinations (01 and 10) for the output SR latch by inverting the data input signal (both the circuits split the single D signal in two complementary S and R signals). The difference is that NAND logical gates are used in the gated D latch, while SR NAND latches are used in the positive-edge-triggered D flip-flop. The role of these latches is to "lock" the active output producing low voltage (a logical zero); thus the positive-edge-triggered D flip-flop can also be thought of as a gated D latch with latched input gates.

Master–slave edge-triggered D flip-flop

[edit]

A master–slave D flip-flop is created by connecting two gated D latches in series, and inverting the enable input to one of them. It is called master–slave because the master latch controls the slave latch's output value Q and forces the slave latch to hold its value whenever the slave latch is enabled, as the slave latch always copies its new value from the master latch and changes its value only in response to a change in the value of the master latch and clock signal.

For a positive-edge triggered master–slave D flip-flop, when the clock signal is low (logical 0) the "enable" seen by the first or "master" D latch (the inverted clock signal) is high (logical 1). This allows the "master" latch to store the input value when the clock signal transitions from low to high. As the clock signal goes high (0 to 1) the inverted "enable" of the first latch goes low (1 to 0) and the value seen at the input to the master latch is "locked". Nearly simultaneously, the twice inverted "enable" of the second or "slave" D latch transitions from low to high (0 to 1) with the clock signal. This allows the signal captured at the rising edge of the clock by the now "locked" master latch to pass through the "slave" latch. When the clock signal returns to low (1 to 0), the output of the "slave" latch is "locked", and the value seen at the last rising edge of the clock is held while the "master" latch begins to accept new values in preparation for the next rising clock edge.

Removing the leftmost inverter in the circuit creates a D-type flip-flop that strobes on the falling edge of a clock signal. This has a truth table like this:

D Q > Qnext 0 X Falling 0 1 X Falling 1

Dual-edge-triggered D flip-flop

[edit]

Flip-Flops that read in a new value on the rising and the falling edge of the clock are called dual-edge-triggered flip-flops. Such a flip-flop may be built using two single-edge-triggered D-type flip-flops and a multiplexer, or by using two single-edge triggered D-type flip-flops and three XOR gates.

Edge-triggered dynamic D storage element

[edit]

An efficient functional alternative to a D flip-flop can be made with dynamic circuits (where information is stored in a capacitance) as long as it is clocked often enough; while not a true flip-flop, it is still called a flip-flop for its functional role. While the master–slave D element is triggered on the edge of a clock, its components are each triggered by clock levels. The "edge-triggered D flip-flop", as it is called even though it is not a true flip-flop, does not have the master–slave properties.

Edge-triggered D flip-flops are often implemented in integrated high-speed operations using dynamic logic. This means that the digital output is stored on parasitic device capacitance while the device is not transitioning. This design facilitates resetting by simply discharging one or more internal nodes. A common dynamic flip-flop variety is the true single-phase clock (TSPC) type which performs the flip-flop operation with little power and at high speeds. However, dynamic flip-flops will typically not work at static or low clock speeds: given enough time, leakage paths may discharge the parasitic capacitance enough to cause the flip-flop to enter invalid states.

T flip-flop

[edit]

If the T input is high, the T flip-flop changes state ("toggles") whenever the clock input is strobed. If the T input is low, the flip-flop holds the previous value. This behavior is described by the characteristic equation:

- (expanding the XOR operator)

and can be described in a truth table:

T flip-flop operation[28] Characteristic table Excitation table Comment Comment 0 0 0 Hold state (no clock) 0 0 0 No change 0 1 1 Hold state (no clock) 1 1 0 No change 1 0 1 Toggle 0 1 1 Complement 1 1 0 Toggle 1 0 1 Complement

When T is held high, the toggle flip-flop divides the clock frequency by two; that is, if clock frequency is 4 MHz, the output frequency obtained from the flip-flop will be 2 MHz. This "divide by" feature has application in various types of digital counters. A T flip-flop can also be built using a JK flip-flop (J & K pins are connected together and act as T) or a D flip-flop (T input XOR Qprevious drives the D input).

JK flip-flop

[edit]

The JK flip-flop augments the behavior of the SR flip-flop (J: Set, K: Reset) by interpreting the J = K = 1 condition as a "flip" or toggle command. Specifically, the combination J = 1, K = 0 is a command to set the flip-flop; the combination J = 0, K = 1 is a command to reset the flip-flop; and the combination J = K = 1 is a command to toggle the flip-flop, i.e., change its output to the logical complement of its current value. Setting J = K = 0 maintains the current state. To synthesize a D flip-flop, simply set K equal to the complement of J (input J will act as input D). Similarly, to synthesize a T flip-flop, set K equal to J. The JK flip-flop is therefore a universal flip-flop, because it can be configured to work as an SR flip-flop, a D flip-flop, or a T flip-flop.

The characteristic equation of the JK flip-flop is:

and the corresponding truth table is:

JK flip-flop operation[28] Characteristic table Excitation table J K Comment Qnext Q Qnext Comment J K 0 0 Hold state Q 0 0 No change 0 X 0 1 Reset 0 0 1 Set 1 X 1 0 Set 1 1 0 Reset X 1 1 1 Toggle Q 1 1 No change X 0

Timing considerations

[edit]Timing parameters

[edit]

The input must be held steady in a period around the rising edge of the clock known as the aperture. Imagine taking a picture of a frog on a lily-pad.[29] Suppose the frog then jumps into the water. If you take a picture of the frog as it jumps into the water, you will get a blurry picture of the frog jumping into the water—it's not clear which state the frog was in. But if you take a picture while the frog sits steadily on the pad (or is steadily in the water), you will get a clear picture. In the same way, the input to a flip-flop must be held steady during the aperture of the flip-flop.

Setup time is the minimum amount of time the data input should be held steady before the clock event, so that the data is reliably sampled by the clock.

Hold time is the minimum amount of time the data input should be held steady after the clock event, so that the data is reliably sampled by the clock.

Aperture is the sum of setup and hold time. The data input should be held steady throughout this time period.[29]

Recovery time is the minimum amount of time the asynchronous set or reset input should be inactive before the clock event, so that the data is reliably sampled by the clock. The recovery time for the asynchronous set or reset input is thereby similar to the setup time for the data input.

Removal time is the minimum amount of time the asynchronous set or reset input should be inactive after the clock event, so that the data is reliably sampled by the clock. The removal time for the asynchronous set or reset input is thereby similar to the hold time for the data input.

Short impulses applied to asynchronous inputs (set, reset) should not be applied completely within the recovery-removal period, or else it becomes entirely indeterminable whether the flip-flop will transition to the appropriate state. In another case, where an asynchronous signal simply makes one transition that happens to fall between the recovery/removal time, eventually the flip-flop will transition to the appropriate state, but a very short glitch may or may not appear on the output, dependent on the synchronous input signal. This second situation may or may not have significance to a circuit design.

Set and Reset (and other) signals may be either synchronous or asynchronous and therefore may be characterized with either Setup/Hold or Recovery/Removal times, and synchronicity is very dependent on the design of the flip-flop.

Differentiation between Setup/Hold and Recovery/Removal times is often necessary when verifying the timing of larger circuits because asynchronous signals may be found to be less critical than synchronous signals. The differentiation offers circuit designers the ability to define the verification conditions for these types of signals independently.

Metastability

[edit]Flip-flops are subject to a problem called metastability, which can happen when two inputs, such as data and clock or clock and reset, are changing at about the same time. When the order is not clear, within appropriate timing constraints, the result is that the output may behave unpredictably, taking many times longer than normal to settle to one state or the other, or even oscillating several times before settling. Theoretically, the time to settle down is not bounded. In a computer system, this metastability can cause corruption of data or a program crash if the state is not stable before another circuit uses its value; in particular, if two different logical paths use the output of a flip-flop, one path can interpret it as a 0 and the other as a 1 when it has not resolved to stable state, putting the machine into an inconsistent state.[30]

The metastability in flip-flops can be avoided by ensuring that the data and control inputs are held valid and constant for specified periods before and after the clock pulse, called the setup time (tsu) and the hold time (th) respectively. These times are specified in the data sheet for the device, and are typically between a few nanoseconds and a few hundred picoseconds for modern devices. Depending upon the flip-flop's internal organization, it is possible to build a device with a zero (or even negative) setup or hold time requirement but not both simultaneously.

Unfortunately, it is not always possible to meet the setup and hold criteria, because the flip-flop may be connected to a real-time signal that could change at any time, outside the control of the designer. In this case, the best the designer can do is to reduce the probability of error to a certain level, depending on the required reliability of the circuit. One technique for suppressing metastability is to connect two or more flip-flops in a chain, so that the output of each one feeds the data input of the next, and all devices share a common clock. With this method, the probability of a metastable event can be reduced to a negligible value, but never to zero. The probability of metastability gets closer and closer to zero as the number of flip-flops connected in series is increased. The number of flip-flops being cascaded is referred to as the "ranking"; "dual-ranked" flip flops (two flip-flops in series) is a common situation.

So-called metastable-hardened flip-flops are available, which work by reducing the setup and hold times as much as possible, but even these cannot eliminate the problem entirely. This is because metastability is more than simply a matter of circuit design. When the transitions in the clock and the data are close together in time, the flip-flop is forced to decide which event happened first. However fast the device is made, there is always the possibility that the input events will be so close together that it cannot detect which one happened first. It is therefore logically impossible to build a perfectly metastable-proof flip-flop. Flip-flops are sometimes characterized for a maximum settling time (the maximum time they will remain metastable under specified conditions). In this case, dual-ranked flip-flops that are clocked slower than the maximum allowed metastability time will provide proper conditioning for asynchronous (e.g., external) signals.

Propagation delay

[edit]Another important timing value for a flip-flop is the clock-to-output delay (common symbol in data sheets: tCO) or propagation delay (tP), which is the time a flip-flop takes to change its output after the clock edge. The time for a high-to-low transition (tPHL) is sometimes different from the time for a low-to-high transition (tPLH).

When cascading flip-flops which share the same clock (as in a shift register), it is important to ensure that the tCO of a preceding flip-flop is longer than the hold time (th) of the following flip-flop, so data present at the input of the succeeding flip-flop is properly "shifted in" following the active edge of the clock. This relationship between tCO and th is normally guaranteed if the flip-flops are physically identical. Furthermore, for correct operation, it is easy to verify that the clock period has to be greater than the sum tsu + th.

Generalizations

[edit]Flip-flops can be generalized in at least two ways: by making them 1-of-N instead of 1-of-2, and by adapting them to logic with more than two states. In the special cases of 1-of-3 encoding, or multi-valued ternary logic, such an element may be referred to as a flip-flap-flop.[31]

In a conventional flip-flop, exactly one of the two complementary outputs is high. This can be generalized to a memory element with N outputs, exactly one of which is high (alternatively, where exactly one of N is low). The output is therefore always a one-hot (respectively one-cold) representation. The construction is similar to a conventional cross-coupled flip-flop; each output, when high, inhibits all the other outputs.[32] Alternatively, more or less conventional flip-flops can be used, one per output, with additional circuitry to make sure only one at a time can be true.[33]

Another generalization of the conventional flip-flop is a memory element for multi-valued logic. In this case the memory element retains exactly one of the logic states until the control inputs induce a change.[34] In addition, a multiple-valued clock can also be used, leading to new possible clock transitions.[35]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Alternatively, the two inputs may be called set 1 and set 0, which may clear confusion for some: the term set alone may be misunderstood as setting the bit to the input provided to set. This naming also makes it intuitive in the explanation below that trying to set 0 and 1 at the same time should make the SR latch behave unpredictably.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ For example, Digital Equipment Corporation's Logic Handbook Flip Chip™ Modules 1969 edition calls transparent RS latches as "R/S Flip Flops" (http://www.bitsavers.org/pdf/dec/handbooks/Digital_Logic_Handbook_1969.pdf page 44)

- ^ Another example, from Digital Equipment Corporation's Logic Handbook Flip Chip™ Modules 1969 edition describes "R/S Flip-Flops" and 'Clocked' "R/S Flip-Flops" accompanied by a truth table. (http://www.bitsavers.org/pdf/dec/handbooks/Digital_Logic_Handbook_1969.pdf page 8)

- ^ Pedroni, Volnei A. (2008). Digital electronics and design with VHDL. Morgan Kaufmann. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-12-374270-4.

- ^ Latches and Flip Flops Archived 2016-10-05 at the Wayback Machine (EE 42/100 Lecture 24 from Berkeley) "...Sometimes the terms flip-flop and latch are used interchangeably..."

- ^ a b Roth, Charles H. Jr. (1995). "Latches and Flip-Flops". Fundamentals of Logic Design (4th ed.). PWS. ISBN 9780534954727.

- ^ GB 148582, Eccles, William Henry & Jordan, Frank Wilfred, "Improvements in ionic relays", published 1920-08-05

- ^ See:

- Eccles, W.H.; Jordan, F.W. (19 September 1919). "A trigger relay utilizing three-electrode thermionic vacuum tubes". The Electrician. 83: 298.

- Reprinted in: Eccles, W.H.; Jordan, F.W. (December 1919). "A trigger relay utilizing three-electrode thermionic vacuum tubes". The Radio Review. 1 (3): 143–6.

- Summary in: Eccles, W.H.; Jordan, F.W. (1919). "A trigger relay utilising three electrode thermionic vacuum tubes". Report of the Eighty-seventh Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science: Bournemouth: 1919, September 9–13. pp. 271–2.

- ^ Pugh, Emerson W.; Johnson, Lyle R.; Palmer, John H. (1991). IBM's 360 and early 370 systems. MIT Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-262-16123-7.

- ^ Flowers, Thomas H. (1983), "The Design of Colossus", Annals of the History of Computing, 5 (3): 249, doi:10.1109/MAHC.1983.10079, S2CID 39816473, archived from the original on 2006-03-26, retrieved 2015-06-16

- ^ Gates, Earl D. (2000). Introduction to electronics (4th ed.). Delmar Thomson (Cengage) Learning. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-7668-1698-5.

- ^ Fogiel, Max; Gu, You-Liang (1998). The Electronics problem solver, Volume 1 (revised ed.). Research & Education Assoc. p. 1223. ISBN 978-0-87891-543-9.

- ^ Lindley, P.L. (August 1968). "letter dated June 13, 1968". EDN.

- ^

Phister, Montgomery (1958). Logical Design of Digital Computers. Wiley. p. 128. ISBN 9780608102658.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ US 2850566, Nelson, Eldred C., "High-speed printing system", published 1958-09-02, assigned to Hughes Aircraft Co.

- ^ Langholz, Gideon; Kandel, Abraham; Mott, Joe L. (1998). Foundations of Digital Logic Design. World Scientific. p. 344. ISBN 978-981-02-3110-1.

- ^ "Summary of the Types of Flip-flop Behaviour" Archived 2018-04-19 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 16 April 2018.

- ^ Hinrichsen, Diederich; Pritchard, Anthony J. (2006). "Example 1.5.6 (R–S latch and J–K latch)". Mathematical Systems Theory I: Modelling, State Space Analysis, Stability and Robustness. Springer. pp. 63–64. ISBN 9783540264101.

- ^ Farhat, Hassan A. (2004). Digital design and computer organization. Vol. 1. CRC Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-8493-1191-8.

- ^ a b Kogge, Peter M. (1981). The Architecture of Pipelined Computers. McGraw-Hill. pp. 25–27. ISBN 0-07-035237-2.

- ^ Cotten, L. W. (1965). "Circuit implementation of high-speed pipeline systems". Proceedings of the November 30--December 1, 1965, fall joint computer conference, Part I on XX - AFIPS '65 (Fall, part I). pp. 489–504. doi:10.1145/1463891.1463945. S2CID 15955626.

- ^ Earle, John G. (March 1965). "Latched Carry-Save Adder". IBM Technical Disclosure Bulletin. 7 (10): 909–910.

- ^ a b Omondi, Amos R. (1999). The Microarchitecture of Pipelined and Superscalar Computers. Springer. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-0-7923-8463-2.

- ^ a b Kunkel, Steven R.; Smith, James E. (May 1986). "Optimal Pipelining in Supercomputers". ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News. 14 (2). ACM: 404–411 [406]. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.99.2773. doi:10.1145/17356.17403. ISSN 0163-5964. S2CID 2733845.

- ^ "The D Flip-Flop". Archived from the original on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2016-06-05.

- ^ "Edge-Triggered Flip-flops". Archived from the original on 2013-09-08. Retrieved 2011-12-15.

- ^ Eckert, J. (1953). "A Survey of Digital Computer Memory Systems". Proceedings of the IRE. 41 (10): 1393–1406. doi:10.1109/JRPROC.1953.274316.

- ^ SN7474 TI datasheet

- ^ a b Mano, M. Morris; Kime, Charles R. (2004). Logic and Computer Design Fundamentals, 3rd Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Pearson Education International. p. 283. ISBN 0-13-191165-1.

- ^ a b Harris, S; Harris, D (2016). Digital Design and Computer Architecture - ARM Edition. Morgan Kaufmann, Waltham, MA. ISBN 978-0-12-800056-4.

- ^ Chaney, Thomas J.; Molnar, Charles E. (April 1973). "Anomalous Behavior of Synchronizer and Arbiter Circuits". IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-22 (4): 421–422. doi:10.1109/T-C.1973.223730. ISSN 0018-9340. S2CID 12594672.

- ^ Often attributed to Don Knuth (1969) (see Midhat J. Gazalé (2000). Number: from Ahmes to Cantor. Princeton University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-691-00515-7.), the term flip-flap-flop actually appeared much earlier in the computing literature, for example, Bowdon, Edward K. (1960). The design and application of a "flip-flap-flop" using tunnel diodes (Master's thesis). University of North Dakota., and in Alexander, W. (Feb 1964). "The ternary computer". Electronics and Power. 10 (2). IET: 36–39. doi:10.1049/ep.1964.0037.

- ^ "Ternary "flip-flap-flop"". Archived from the original on 2009-01-05. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- ^ US 6975152, Lapidus, Peter D., "Flip flop supporting glitchless operation on a one-hot bus and method", published 2005-12-13, assigned to Advanced Micro Devices Inc.

- ^ Irving, Thurman A.; Shiva, Sajjan G.; Nagle, H. Troy (March 1976). "Flip-Flops for Multiple-Valued Logic". IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-25 (3): 237–246. doi:10.1109/TC.1976.5009250. S2CID 34323423.

- ^ Wu, Haomin; Zhuang Nan (July 1991). "Research into ternary edge-triggered JKL flip-flop". Journal of Electronics (China). 8 (3): 268–275. doi:10.1007/BF02778378. S2CID 61275953.

External links

[edit]- FlipFlop Hierarchy Archived 2015-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, shows interactive flipflop circuits.

- The J-K Flip-Flop

- Flip-Flop in Digital Electronics

- Shirriff, Ken (August 2022). "Reverse-engineering a 1960s hybrid flip flop module with X-ray CT scans".

Flip-flop (electronics)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and purpose

A flip-flop is a bistable multivibrator circuit in digital electronics that maintains one of two stable states, representing binary values 0 or 1, until an external input triggers a change to the other state.[7] This bistability arises from a feedback loop where the output reinforces itself, indicating the state persists without further input. Flip-flops serve as fundamental memory elements in sequential logic circuits, enabling the storage and synchronization of data for applications such as counters, shift registers, and finite state machines.[8] Unlike combinational logic, which produces outputs solely from current inputs, flip-flops incorporate memory of prior states, allowing circuits to process information over time.[8] In a basic block diagram, a flip-flop typically features inputs such as data (D), set (S), reset (R), clock (CLK), or others depending on the type, with outputs Q (the stored state) and (its complement). These components form the core of processors and memory units, where arrays of flip-flops store instructions and data.[7] While flip-flops are edge-triggered for precise timing, they differ from level-sensitive latches in their response to control signals.Latches versus flip-flops

Latches are level-triggered storage elements in digital electronics that remain transparent to their input signals while the enable signal is active, allowing the output to continuously follow the input, and hold their state when the enable signal is inactive.[9][10] This level-sensitive behavior makes latches suitable for asynchronous or simple temporary storage applications.[2] In contrast, flip-flops are edge-triggered devices that update their output state only at the transition of a clock signal, such as the rising or falling edge, regardless of the clock's level duration.[10][2] This ensures precise synchronization in sequential circuits, where state changes are confined to specific instants.[9] The operational differences between latches and flip-flops are summarized in the following comparison:| Aspect | Latch | Flip-Flop |

|---|---|---|

| Transparency | Continuous during enable signal active | Instantaneous only at clock edge |

| Susceptibility to glitches | Higher, due to ongoing input propagation while enabled | Lower, with proper edge detection and design to isolate inputs |

Historical Development

Invention of the bistable circuit

The bistable circuit, foundational to the flip-flop, was first invented in 1918 by British physicists William Henry Eccles and Frank Wilfred Jordan as the Eccles-Jordan trigger circuit, a multivibrator using vacuum tubes.[4] This device employed two triode vacuum tubes cross-coupled such that the grid of one tube connected through a resistor to the plate of the other, enabling the circuit to maintain one of two stable states after an initial trigger pulse.[3] The invention was patented on June 21, 1918, under the title "Improvements in Ionic Relays" (British Patent 148,582, granted 1920), and detailed in their seminal one-page paper "A trigger relay utilizing three-electrode thermionic vacuum tubes," published in The Electrician on September 19, 1919.[4] The basic Eccles-Jordan circuit diagram features two triode tubes (V1 and V2), each with a cathode grounded via a common resistor, an anode load resistor connected to a positive supply (e.g., +B), and cross-coupling where the anode of V1 connects to the grid of V2 via resistor R1, and the anode of V2 connects to the grid of V1 via resistor R2, with grid leak resistors to bias the non-conducting tube negatively.[3] In operation, one tube conducts while the other is cut off, holding the state until a positive input pulse to the non-conducting tube's grid or a negative pulse to the conducting tube's grid triggers a switch, with regenerative feedback ensuring rapid transition.[4] Initially applied in the 1920s and 1930s, the Eccles-Jordan circuit served as a core element in electronic counters for scaling pulses and in oscillators for generating stable signals in telegraphy and telephony systems.[4] Its bistable nature allowed reliable pulse division in early scaling circuits, though practical implementations were constrained by vacuum tube limitations.[7] A landmark digital computing application came in 1943 with Tommy Flowers' design of the Colossus computer at Bletchley Park, where Eccles-Jordan triggers formed the memory and shift register elements for codebreaking the Lorenz cipher during World War II.[3] Due to the slow switching times and capacitance in vacuum tubes, these early circuits operated at low speeds, approximately 5 kHz, restricting their use to non-real-time processing tasks.[4]Evolution to modern forms

Following World War II, the development of semiconductor transistors in the late 1940s and early 1950s marked a pivotal shift in flip-flop technology, replacing bulky and power-hungry vacuum tubes with more compact, reliable, and faster alternatives. Transistors enabled bistable circuits to operate at higher speeds and lower voltages, reducing size and heat dissipation in digital systems. For instance, Texas Instruments announced the first commercial silicon transistors in 1954, which offered superior temperature stability and performance compared to earlier germanium types, facilitating the transition to transistorized flip-flops in early computers like the U.S. Air Force's TRADIC system completed in 1954.[12] By the 1960s, the advent of integrated circuits standardized flip-flop implementations through logic families such as resistor-transistor logic (RTL) and diode-transistor logic (DTL). Fairchild Semiconductor introduced the first commercial RTL integrated circuits in 1961 under the μLogic brand, including JK flip-flops like the Type 923, which integrated multiple transistors on a single chip for improved reliability and cost-effectiveness in applications like the Apollo Guidance Computer. DTL followed soon after, with Fairchild's 930 series in 1964 providing better noise immunity via diode inputs, further refining standardized flip-flop designs for broader adoption in minicomputers and data processing equipment.[13][14] The 1970s brought a focus on power efficiency with the rise of complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology, which minimized static power consumption while maintaining compatibility with TTL voltage levels. This era saw the development of low-power flip-flop ICs, exemplified by the 74HC series, including the 74HC74 dual D-type flip-flop introduced in 1978 by manufacturers like Signetics and Texas Instruments, enabling battery-operated and portable digital devices. A significant milestone occurred in 1971 with the Intel 4004, the first commercial microprocessor, which incorporated D flip-flops to form its 4-bit registers and arithmetic logic unit, integrating thousands of transistors on a single chip for programmable computing.[15][16] Moore's Law, articulated by Gordon Moore in 1965, profoundly influenced flip-flop evolution by predicting the doubling of transistor density on integrated circuits approximately every two years, directly scaling the number and complexity of flip-flops in very large scale integration (VLSI) designs. This exponential growth allowed VLSI chips in the late 1970s and beyond to pack millions of flip-flops for advanced processors and memory systems, enhancing performance while reducing costs per function.[17]Implementation

Gate-level configurations

The basic bistable circuits underlying flip-flops, known as latches, are constructed at the gate level using cross-coupled logic gates to create a feedback loop that maintains bistability, allowing the circuit to store one bit of information in one of two stable states. This configuration typically involves two gates—such as NOR or NAND—where the output of each gate serves as an input to the other, forming a positive feedback mechanism that reinforces the current state until external inputs alter it. The general schematic features two inputs (commonly labeled S for set and R for reset), two complementary outputs (Q and \overline{Q}), and the feedback loop ensures that in valid states, the outputs are always opposite: one high and one low, preventing both from being high or both low simultaneously.[8] Common configurations employ either cross-coupled NOR gates or cross-coupled NAND gates, each suited to different input polarities. The NOR-based configuration operates with active-high inputs, where a high signal on S sets Q to 1 and a high on R resets Q to 0, making it suitable for positive logic systems. In contrast, the NAND-based configuration uses active-low inputs, requiring a low signal on S to set Q to 1 and a low on R to reset Q to 0, which aligns with negative logic conventions and is often preferred in CMOS implementations for its compatibility with pull-up networks. These setups achieve bistability through the inherent inverting nature of the gates, where small perturbations are amplified to drive the outputs to full rail levels.[8][18] To create synchronous flip-flops from these basic latches, additional logic gates are used to incorporate a clock signal, enabling edge-triggered operation. For example, a clocked SR flip-flop adds AND gates to the S and R inputs, allowing state changes only when the clock is high (for level-sensitive) or using more complex master-slave configurations for true edge-triggering. This ensures controlled transitions synchronized to the clock, forming the foundation for types like D and JK flip-flops described elsewhere.[1] In asynchronous designs, such as basic SR latches built from these cross-coupled gates, forbidden states arise when both inputs are asserted simultaneously, leading to invalid output conditions. For the NOR configuration, applying S=1 and R=1 forces both Q and \overline{Q} to 0, creating a metastable or undefined state upon release. Similarly, in the NAND configuration, S=0 and R=0 drives both outputs to 1, again resulting in an indeterminate condition. Race conditions can also occur if S and R change nearly simultaneously, causing temporary oscillations or unpredictable transitions due to differing gate propagation delays in the feedback loop.[8] The set-reset behavior of these gate-level configurations follows a generic truth table, illustrated below for the NOR-based SR latch (active-high inputs), where the hold state preserves the previous output when both inputs are deasserted:| S | R | Q (next) | \overline{Q} (next) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | Q (prev) | \overline{Q} (prev) | Hold |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Set |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Reset |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Forbidden |

Characteristic representations

Characteristic equations provide a mathematical description of a flip-flop's next-state behavior, typically expressed in the general form , where is the output state after the clock edge, is the current state, and the function depends on the specific inputs and clock transition.[19] These equations abstract the flip-flop's response, enabling analysis without detailed circuit implementation, and are derived from the logic gates' truth tables.[19] For instance, in edge-triggered designs, the clock input synchronizes the transition, ensuring the next state is evaluated only at the active edge.[19] Excitation tables complement characteristic equations by specifying the input combinations required to drive a flip-flop from its current state to a desired next state .[20] These tables are essential for sequential circuit design, as they reverse the characteristic table to determine necessary inputs for specific transitions like hold (no change), set (to 1), reset (to 0), or toggle (invert).[1] For example, to achieve a toggle transition in a T-type configuration, the input must be set to 1 regardless of the current state, while a hold requires the input to be 0.[20]| Current State | Next State | T Input (for toggle example) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 (hold) | 0 |

| 0 | 1 (toggle) | 1 |

| 1 | 1 (hold) | 0 |

| 1 | 0 (toggle) | 1 |

Types

Asynchronous set-reset latches

Asynchronous set-reset latches, also known as SR latches, are fundamental bistable circuits in digital electronics that store one bit of information and respond immediately to asynchronous set (S) and reset (R) inputs without requiring a clock signal for operation. These latches maintain their state until an input changes it, providing the basic building block for more complex sequential logic. They operate in a level-sensitive manner, where the outputs Q (the stored value) and \bar{Q} (its complement) are determined directly by the logic levels of S and R.[2] The SR NOR latch is implemented using two cross-coupled NOR gates, forming a feedback loop that ensures bistability. The set input S is applied to one input of the first NOR gate, whose output is Q, while the second input of this gate receives \bar{Q} from the second NOR gate. The reset input R is applied to one input of the second NOR gate, whose output is \bar{Q}, with Q fed back to its second input. This configuration uses active-high inputs, where asserting S=1 sets Q=1 (and \bar{Q}=0), asserting R=1 resets Q=0 (and \bar{Q}=1), and deasserting both (S=0, R=0) holds the previous state. However, the state S=1 and R=1 is forbidden, as it forces both Q=0 and \bar{Q}=0, leading to unpredictable recovery upon release.[23] The truth table for the SR NOR latch is as follows:| S | R | Q^{+} | \bar{Q}^{+} | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | Q | \bar{Q} | Hold (no change) |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Reset |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Set |

| 1 | 1 | ? | ? | Forbidden |

| S | R | Q^{+} | \bar{Q}^{+} | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Q | \bar{Q} | Hold (no change) |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Reset |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Set |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Forbidden |

| S | R | Q^{+} | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | Q | Hold |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | Reset |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | Set |

| 1 | 1 | ? | Undefined (race possible) |

| J | K | Q^{+} | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | Q | Hold |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | Reset |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | Set |

| 1 | 1 | \bar{Q} | Toggle |

Gated latches and conditional transparency

Gated latches, also known as level-sensitive latches, incorporate an enable signal (often denoted as E or CLK) that controls the timing of state changes, allowing the latch to be conditionally transparent to its inputs. When the enable is active (typically high), the latch output follows the input values, enabling data to propagate through; when inactive (low), the latch holds its previous state, preventing changes. This mechanism provides controlled access to the bistable storage of the underlying SR latch while avoiding constant asynchronous behavior.[19] The gated SR latch extends the basic SR latch by adding AND gates to the set (S) and reset (R) inputs, gating them with the enable signal E. It functions transparently when E=1, where the next state follows the SR latch equation ; when E=0, it latches the current state regardless of S and R. The full characteristic equation is , ensuring no state change during disable. A truth table illustrates this behavior:| E | S | R | Q^{+} |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | X | X | Q (no change) |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | Q (hold) |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 (reset) |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 (set) |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | Invalid |

| E | D | Q^{+} |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | X | Q (no change) |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

D flip-flop

The D flip-flop, also known as the data or delay flip-flop, is a fundamental synchronous sequential circuit element that captures the value of its data input (D) and transfers it to the output (Q) on the active clock edge, with the characteristic equation .[20] This behavior ensures that the output reflects the input present at the clock transition, making it ideal for data storage and synchronization in digital systems.[29] The classical positive-edge-triggered D flip-flop operates by sampling the D input on the rising edge of the clock signal, ignoring input changes at other times.[29] It is typically implemented using a master-slave configuration consisting of two gated D latches, where the master latch is transparent (allows data to pass through) when the clock is low and latched when the clock is high, while the slave latch operates in the opposite phases to capture the master's state on the rising edge.[2] This arrangement prevents data races and ensures edge-triggered operation. At the gate level, the circuit can be realized with six NAND gates: the master stage uses three NAND gates forming an SR latch with clocked inputs, and the slave stage mirrors this but with inverted clock polarity, connected such that the master's outputs drive the slave's inputs.[29] This compact design reduces transistor count compared to other configurations while maintaining reliable positive-edge triggering.[2] A variant, the dual-edge-triggered D flip-flop, responds to both rising and falling clock edges, effectively doubling the data rate for a given clock frequency. It achieves this by generating edge-detection pulses using an XOR gate between the clock and a delayed version of itself, which then drives two latches in a configuration that alternates sampling on each edge.[30] This approach is particularly useful in high-speed applications like serializers/deserializers, though it introduces additional clock skew considerations. For power- and area-sensitive designs, the edge-triggered dynamic D flip-flop employs capacitors for charge-based storage rather than static feedback loops.[31] In this master-slave structure, dynamic nodes (parasitic gate, junction, and overlap capacitances) hold the state as charge during the evaluation phase, with the master precharging on clock low and evaluating on clock high, followed by the slave capturing on the opposite transition; the characteristic equation remains , but the stored charge must be refreshed periodically due to leakage currents, limiting hold times to milliseconds.[31] The circuit uses fewer transistors (typically eight in CMOS) than static versions, enabling higher speed and lower power at the cost of refresh overhead.[31] The characteristic table for a D flip-flop illustrates its operation, where only the D input and clock edge determine the next state , with no dependency on the current state Q for excitation—the input D directly sets .| D | Q | Operation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | No change (reset) |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | Reset |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | Set |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | No change (set) |

T flip-flop

The T flip-flop, also known as the toggle flip-flop, is a bistable sequential logic device that stores one bit of information and changes its output state in response to a clock signal based on a single toggle input, denoted as T.[2] It operates such that if the T input is logic 0, the next state of the output Q (denoted Q^{+}) remains the same as the current state Q on the active clock edge; if T is logic 1, Q^{+} inverts from Q.[32] The behavior is captured by the characteristic equation , where \oplus denotes the exclusive-OR operation.[2] A T flip-flop is typically implemented using a D flip-flop with feedback logic to achieve the toggle functionality. The D input of the underlying D flip-flop is connected to the output of an XOR gate whose inputs are the T signal and the current Q output, ensuring D = Q \oplus T; this configuration leverages the D flip-flop's data-latching property to produce the toggle effect when T=1.[2] For edge-triggered operation, a master-slave arrangement is employed, where the master latch captures the input during one clock phase and the slave transfers it on the edge, preventing race conditions during state transitions.[32] The operation of a T flip-flop is summarized in its characteristic truth table, which shows the next output state Q(t+1) based on the current state Q(t) and input T:| T | Q(t) | Q(t+1) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Q(t) | Q(t+1) | T |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

JK flip-flop

The JK flip-flop is a versatile sequential logic device that builds upon the basic principles of the SR latch, providing defined behavior for all input combinations, including the previously forbidden state where both inputs are asserted.[2] It features two inputs, J and K, along with a clock input in its synchronous form, enabling set, reset, hold, and toggle operations. The device's characteristic equation, which defines the next state based on current state and inputs, is given by: This equation ensures that when J=1 and K=0, the output sets to 1; when J=0 and K=1, it resets to 0; when J=K=1, it toggles to the complement of the current state; and when J=K=0, it holds the current state.[32] Unlike the SR latch, the JK configuration eliminates undefined states, making it suitable for reliable sequential circuits.[36] The asynchronous JK latch consists of a cross-coupled pair of NOR or NAND gates with additional AND gates incorporating feedback from the outputs to the inputs.[37] In this basic form, the J input is ANDed with the complement of Q before feeding into the set path, and the K input is ANDed with Q before the reset path, preventing the race condition that occurs in the SR latch when both inputs are high by instead causing a toggle if the inputs remain asserted long enough.[2] This design allows the latch to respond directly to input changes without a clock, maintaining bistability while avoiding metastable or oscillatory behavior in the invalid input case.[37] For synchronous operation, the clocked JK flip-flop typically employs a master-slave configuration, where two JK latches are cascaded such that the master latch is enabled during one clock phase and the slave during the other, ensuring edge-triggered behavior.[38] This arrangement resolves potential race conditions during the toggle mode (J=K=1) by isolating the input sampling from output propagation, preventing feedback from affecting the master while the slave transfers the state on the clock edge.[18] The result is a positive edge-triggered device that updates only on the rising clock transition, commonly implemented with NAND or NOR logic gates.[38] The behavior of the JK flip-flop is summarized in its characteristic table, which shows the next state for all combinations of J, K, and current Q (assuming a clock edge occurs):| J | K | Q | Q⁺ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Q | Q⁺ | J | K |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | X |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | X |

| 1 | 0 | X | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | X | 0 |

| Pin | Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CLK₁ | Clock input for flip-flop 1 (negative edge) |

| 2 | J₁ | J input for flip-flop 1 |

| 3 | K₁ | K input for flip-flop 1 |

| 4 | PRE̅₁ | Asynchronous preset (active low) for flip-flop 1 |

| 5 | Q₁ | Q output for flip-flop 1 |

| 6 | Q̅₁ | Complementary output for flip-flop 1 |

| 7 | CLR̅₁ | Asynchronous clear (active low) for flip-flop 1 |

| 8 | GND | Ground |

| 9 | CLK₂ | Clock input for flip-flop 2 |

| 10 | J₂ | J input for flip-flop 2 |

| 11 | K₂ | K input for flip-flop 2 |

| 12 | Q̅₂ | Complementary output for flip-flop 2 |

| 13 | Q₂ | Q output for flip-flop 2 |

| 14 | PRE̅₂ | Asynchronous preset (active low) for flip-flop 2 |

| 15 | CLR̅₂ | Asynchronous clear (active low) for flip-flop 2 |

| 16 | V_{CC} | Positive supply (5V) |

Timing Considerations

Timing parameters

Timing parameters are critical specifications that dictate the reliable operation of flip-flops in synchronous digital circuits, ensuring that inputs are properly captured and outputs are generated without errors during clock transitions. These parameters define the windows around clock edges where signals must meet stability requirements, primarily for edge-triggered devices like the D flip-flop. Violations of these timings can lead to incorrect latching or, in severe cases, metastable states, though the focus here is on the definitional specs rather than failure analysis.[15] The setup time, denoted , represents the minimum duration the data input (D) must be held stable prior to the active edge of the clock signal to guarantee that the flip-flop correctly samples the input value. For a positive edge-triggered flip-flop, this stability is required before the rising clock edge. Typical values for commercial devices vary with supply voltage and temperature, but they establish the constraint on the maximum combinational logic delay between flip-flops in a clock domain.[15][42] The hold time, , is the minimum time the data input must remain stable following the active clock edge to prevent the flip-flop from inadvertently capturing a subsequent input change. Unlike setup time, hold time is often zero or negative in modern CMOS flip-flops, meaning the input can change immediately after the clock edge without issue, which simplifies downstream logic timing. This parameter ensures that race conditions do not corrupt the latched value due to fast signal transitions.[15][42] The clock-to-output delay, commonly or (CLK to Q), measures the time elapsed from the active clock edge until the output (Q or \overline{Q}) becomes valid and stable with the new value. This delay includes internal propagation through the flip-flop's gates and is influenced by load capacitance and voltage; it directly impacts the minimum clock period in pipelined systems by limiting the available time for logic evaluation. Maximum values are used in timing analysis to avoid setup violations in the receiving flip-flop.[15][42] For flip-flops with asynchronous inputs such as preset (set) or clear (reset), the recovery time is the minimum duration these inputs must be inactive (deasserted) before the active clock edge to allow the flip-flop to respond correctly to the clock without interference from the async signal. The removal time , conversely, is the minimum time the async input must remain inactive after the clock edge to ensure the synchronous operation proceeds without the async input affecting the output. These parameters are essential for designs using async resets, preventing glitches or incomplete recovery.[43][42] The following table summarizes timing parameters for the SN74HC74 dual D flip-flop at V (tested at 4.5 V conditions) and 25°C, based on manufacturer specifications; values can vary slightly across vendors and operating temperatures from -40°C to 85°C. Note that setup, hold, recovery, and removal times are minimum requirements; clock-to-output has typical and maximum values. Conditions: 50 pF load.| Parameter | Symbol | Minimum (ns) | Typical (ns) | Maximum (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setup time (data) | 20 | - | - | |

| Hold time (data) | 0 | - | - | |

| Clock-to-output delay | - | 15 | 30 | |

| Recovery time (async) | 5 | - | - | |

| Removal time (async) | 6 | - | - |