Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

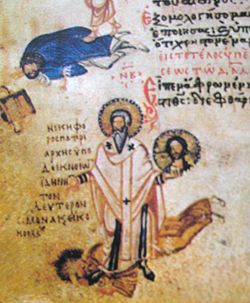

Nikephoros I of Constantinople

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Nicephorus I of Constantinople | |

|---|---|

| Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople | |

| Installed | 12 April 806 |

| Term ended | 13 March 815 |

| Predecessor | Tarasios of Constantinople |

| Successor | Theodotus I of Constantinople |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 758 |

| Died | 5 April 828 |

| Denomination | Chalcedonian Christianity |

Nikephoros I (Greek: Νικηφόρος; c. 758 – 5 April 828) was a Byzantine writer and Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from 12 April 806 to 13 March 815.[1][2]

Life

[edit]He was born in Constantinople as the son of Theodore and Eudokia, of a strictly Orthodox family, which had suffered from the earlier Iconoclasm. His father Theodore, one of the secretaries of Emperor Constantine V, had been scourged and banished to Nicaea for his zealous support of Iconodules,[3] and the son inherited the religious convictions of the father.

While still young Nicephorus was brought to the court, where he became an imperial secretary and entered the service of the Empire. Under Empress Irene of Athens he took part in the synod of 787 of Nicaea as imperial commissioner. He then withdrew to one of the cloisters that he had founded on the Thracian Bosporus. There he devoted himself to ascetic practices and to the study both of secular learning, as grammar, mathematics, and philosophy, and the Scriptures. Around 802 he was recalled and appointed director of the largest hospital for the destitute in Constantinople.[3]

After the death of the Patriarch Tarasios of Constantinople, there was great division among the clergy and higher court officials as to the choice of his successor. Although still a layman, Nicephorus was chosen patriarch by the wish of the emperor (Easter, 12 April 806). The uncanonical choice met with opposition from the strictly clerical party of the Stoudites,[3] and this opposition intensified into an open break when Nicephorus I, in other respects a very rigid moralist, showed himself compliant to the will of the emperor by reinstating the excommunicated priest Joseph.

After vain theological disputes, in December 814, there followed personal insults. Nicephorus I at first replied to his removal from his office by excommunication, but at last, under Emperor Leo V the Armenian was obliged to yield to force, and was taken to one of the cloisters he had founded, Tou Agathou, and later to that called Tou Hagiou Theodorou. From there he carried on a literary polemic for the cause of the iconodules against the synod of 815. On the occasion of the change of emperors, in 820, he was put forward as a candidate for the patriarchate and at least obtained the promise of toleration.

He died at the monastery of Saint Theodore (Hagiou Theodorou), revered as a confessor.[4] His remains were solemnly brought back to Constantinople by Methodios I of Constantinople on 13 March 847 and interred in the Church of the Holy Apostles, where they were annually the object of imperial devotion. His feast is celebrated on this day both in the Greek and Roman Churches; the Greeks also observe 2 June as the day of his death.

Works

[edit]Compared with Theodore the Studite, Nicephorus I appears as a friend of conciliation, learned in patristics, more inclined to take the defensive than the offensive, and possessed of a comparatively chaste, simple style. He was mild in his ecclesiastical and monastical rules and non-partisan in his historical treatment of the period from 602 to 769 (Historia syntomos, breviarium). He used the chronicle of Trajan the Patrician but deliberately chose not to name the source so as to connect himself to the historical tradition of Theophylact Simocatta.[5][6] The Short History is thematically focused around the matter of the offices of emperor and patriarch.[7] Nicephorus I attempted to salvage the reputation of the patriarchate by criticising iconoclast patriarchs for submitting to the emperor, not for being iconoclasts.[8] Emperor Heraclius was the ideal emperor in Nicephorus I's scheme because of how he worked alongside patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople, but also how Sergius I helped to defend Constantinople from the Avars in 626 as well as the patriarch's ability to discipline the emperor for his marriage to his niece Martina. Heraclius failure to heed the Egyptian patriarch's advice is what ultimately brought about the Arab conquest of Egypt.[9]

His tables of universal history, Chronography or Chronographikon Syntomon, in passages extended and continued, were in great favor with the Byzantines, and were also circulated outside the Empire in the Latin version of Anastasius Bibliothecarius, and also in Slavonic translation. The Chronography offered a universal history from the time of Adam and Eve to his own time. To it he appended a canon catalog (which does not include the Book of Revelation of John of Patmos). The catalog of the accepted books of the Old and New Testaments is followed by the antilegomena (including Revelation) and the apocrypha. Next to each book is the count of its lines, his Stichometry of Nicephorus, to which we can compare our accepted texts and judge how much has been added or omitted. This is especially useful for apocrypha for which only fragmentary texts have survived.

The principal works of Nicephorus I are three writings referring to iconoclasm:

- Apologeticus minor, probably composed before 814, an explanatory work for laymen concerning the tradition and the first phase of the iconoclastic movement;

- Apologeticus major with the three Antirrhetici against Mamonas-Constantine Kopronymos, a complete dogmatics of the belief in images, with an exhaustive discussion and refutation of all objections made in opposing writings, as well as those drawn from the works of the Church Fathers;

- The third of these larger works is a refutation of the iconoclastic synod of 815 (ed. Serruys, Paris, 1904).

Nicephorus I follows in the path of John of Damascus. His merit is the thoroughness with which he traced the literary and traditional proofs, and his detailed refutations are serviceable for the knowledge they afford of important texts adduced by his opponents and in part drawn from the older church literature.

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ St. Nicephorus, Patriarch of Constantinople, 806–815, birth about 758; death 5 April 828.

- ^ Paul J. Alexander, The Patriarch Nicephorus of Constantinople, Oxford University Press, 1958.

- ^ a b c Johann Peter Kirsch, "St. Nicephorus", Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 11, New York, Robert Appleton Company, 1911

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Martyrs and Confessors", Orthodox Church in America.

- ^ Treadgold, Warren (2011). "Trajan the Patrician, Nicephorus, and Theophanes". In Bumazhnov, Dmitrij; Grypeou, Emmanouela; Sailors, Timothy B.; Toepel, Alexander (eds.). Bibel, Byzanz, und christlicher Orient - Festschrift für Stephen Gerö zum 65, Geburtstag. Louven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 589–621.

- ^ Marjanović, Dragoljub (2018). Creating Memories in Late 8th-century Byzantium - The Short History of Nikephoros of Constantinople. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 65–70.

- ^ Marjanović, Creating Memories in Late 8th-century Byzantium, 122–126.

- ^ Marjanović, Creating Memories in Late 8th-century Byzantium, 208–214.

- ^ Marjanović, Creating Memories in Late 8th-century Byzantium, 122–147.

External links

[edit]- Development of the Canon of the New Testament - the Stichometry of Nicephorus

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Nicephorus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Nicephorus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Nikephoros I of Constantinople

View on GrokipediaNikephoros I (c. 758 – June 2, 828) was Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from April 12, 806, to March 13, 815, a Byzantine theologian, historian, and confessor who rose from secular administration to ecclesiastical leadership amid the second wave of iconoclasm.[1][2] Born in Constantinople to an Orthodox family persecuted under the first iconoclastic regime, he served as an imperial secretary and represented Empress Irene at the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, which restored icon veneration.[1][2] Elevated to the patriarchate by Emperor Nikephoros I despite his lay status, he initially faced criticism from monastic leaders like Theodore the Studite for decisions such as reinstating a priest, but later reconciled with them under Emperor Michael I.[1][2] His tenure culminated in resolute opposition to Emperor Leo V's revival of iconoclastic policies in 815, refusing to convene a synod endorsing the destruction of religious images and thereby incurring deposition by iconophile bishops and exile to a monastery on the Bosporus.[1][3] From exile, Nikephoros continued producing treatises refuting iconoclasm, including the Antirrhetici and an Apology, while his Breviarium (Short History) provided a critical chronicle of Byzantine history from 602 to 769, preserving accounts of imperial and ecclesiastical events.[1] Venerated as a saint in Orthodox and Catholic traditions for his defense of doctrinal orthodoxy, his relics were later translated to Constantinople, underscoring his enduring legacy as a pillar against imperial interference in theology.[2][3]