Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Salpingitis

View on Wikipedia| Salpingitis | |

|---|---|

| |

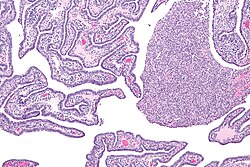

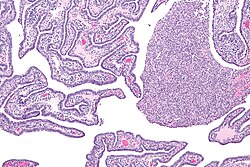

| Micrograph of acute and chronic salpingitis. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

Salpingitis is an infection causing inflammation in the fallopian tubes (also called salpinges). It is often included in the umbrella term of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), along with endometritis, oophoritis, myometritis, parametritis, and peritonitis.[1][2]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]The symptoms usually appear after a menstrual period. The most common are: an abnormal smell and colour of vaginal discharge, fever, nausea, vomiting, bloating, and frequent urination. Pain may be felt during ovulation, during periods, during sexual intercourse, on both sides of the abdomen, and lower back.[3]

Causes

[edit]The infection usually has its origin in the vagina and ascends to the fallopian tube from there. Because the infection can spread via the lymph vessels, infection in one fallopian tube usually leads to infection of the other.[3]

Risk factors

[edit]It's been theorized that retrograde menstrual flow and the cervix opening during menstruation allow the infection to reach the fallopian tubes.

Other risk factors include surgical procedures that break the cervical barrier, such as:

- endometrial biopsy

- curettage

- hysteroscopy[2]

Another risk is factors that alter the microenvironment in the vagina and cervix, allowing infecting organisms to proliferate and eventually ascend to the fallopian tube:

- antibiotic treatment

- ovulation

- menstruation

- sexually transmitted infection (STI)

Finally, sexual intercourse may facilitate the spread of disease from the vagina to the fallopian tube. Coital risk factors are:

- Uterine contractions

- Sperm, carrying organisms upward

Bacterial species

[edit]The bacteria most associated with salpingitis are:[3]

However, salpingitis is usually polymicrobial, involving many kinds of pathogens such as Ureaplasma urealyticum, and anaerobic and aerobic bacteria.

Diagnosis

[edit]Salpingitis may be diagnosed by pelvic examination, blood tests, and/or a vaginal or cervical swab.

Types

[edit]Salpingitis can be acute, chronic, or subclinical.[4]

Epidemiology

[edit]Approximately one in fourteen untreated chlamydia infections will result in salpingitis.[5]

Over one million cases of acute salpingitis are reported every year in the US, but the number of incidents is probably larger, due to incomplete and untimely reporting methods and that many cases are reported first when the illness has gone so far that it has developed chronic complications. For women age 16–25, salpingitis is the most common serious infection. It affects approximately 11% of females of reproductive age.[2]

Salpingitis has a higher incidence among members of lower socioeconomic classes. However, this is thought of as being an effect of earlier sexual debut, multiple partners, and decreased ability to receive proper health care rather than any independent risk factor for salpingitis.

As an effect of an increased risk due to multiple partners, the prevalence of salpingitis is highest for people age 15–24 years. Decreased awareness of symptoms and less will to use contraceptives are also common in this group, raising the occurrence of salpingitis.

Complications

[edit]For those affected, 20% need hospitalization. For those aged 15–44 years, 0.29 per 100,000 die from salpingitis.[2]

One in six cases of salpingitis will lead to infertility.[4] Salpingitis can also lead to tubal factor infertility because the eggs released in ovulation cannot make contact with the sperm. Approximately 75,000-225,000 cases of infertility in the US are caused by salpingitis. The more times one has the infection, the greater the risk of infertility. With one episode of salpingitis, the risk of infertility is 8-17%. With 3 episodes of salpingitis, the risk is 40-60%, although the exact risk depends on the severity of each episode.[2]

Damaged oviducts from salpingitis increase the risk of an ectopic pregnancy by 7-10 fold. Half of ectopic pregnancies are due to a salpingitis infection.[2]

Other complications are:[3]

- Infection of ovaries and uterus

- Infection of sex partners

- An abscess on the ovary

- Internal scars resulting in Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome of the liver[6]

Treatment

[edit]Salpingitis is most commonly caused by bacteria and typically treated with antibiotics.

In other animals

[edit]E. coli, Gallibacterium and other bacteria can cause salpingitis in chickens and other poultry.[7][8] This can result in lower egg production.[8] Dairy cows can also have salpingitis.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Xu, Stacey X.; Gray-Owen, Scott D. (2021-08-16). "Gonococcal Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Placing Mechanistic Insights Into the Context of Clinical and Epidemiological Observations". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 224 (12 Suppl 2): S56 – S63. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiab227. ISSN 1537-6613. PMC 8365115. PMID 34396410.

- ^ a b c d e f Salpingitis at eMedicine

- ^ a b c d "Salpingitis". 16 September 2022.

- ^ a b Curry, A; Williams, T; Penny, ML (15 September 2019). "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention". American Family Physician. 100 (6): 357–364. PMID 31524362.

- ^ Price, Malcolm J.; Ades, A. E.; Soldan, Kate; Welton, Nicky J.; Macleod, John; Simms, Ian; DeAngelis, Daniela; Turner, Katherine Me; Horner, Paddy J. (March 2016). "The natural history of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women: a multi-parameter evidence synthesis". Health Technology Assessment. 20 (22): 1–250. doi:10.3310/hta20220. ISSN 2046-4924. PMC 4819202. PMID 27007215.

- ^ Coremans, Laura; de Clerck, Frederik (2018-03-20). "Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome associated with tuberculous salpingitis and peritonitis: a case presentation and review of literature". BMC Gastroenterology. 18 (1): 42. doi:10.1186/s12876-018-0768-0. ISSN 1471-230X. PMC 5859724. PMID 29558895.

- ^ Narasinakuppe Krishnegowda, Dharanesha; Dhama, Kuldeep; Kumar Mariappan, Asok; Munuswamy, Palanivelu; Iqbal Yatoo, Mohd.; Tiwari, Ruchi; Karthik, Kumaragurubaran; Bhatt, Prakash; Reddy, Maddula Ramakoti (2020). "Etiology, epidemiology, pathology, and advances in diagnosis, vaccine development, and treatment of Gallibacterium anatis infection in poultry: a review". The Veterinary Quarterly. 40 (1): 16–34. doi:10.1080/01652176.2020.1712495. ISSN 0165-2176. PMC 7006735. PMID 31902298.

- ^ a b Mellata, Melha (November 2013). "Human and Avian Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli: Infections, Zoonotic Risks, and Antibiotic Resistance Trends". Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 10 (11): 916–932. doi:10.1089/fpd.2013.1533. ISSN 1535-3141. PMC 3865812. PMID 23962019.

- ^ de Boer, M. W.; LeBlanc, S. J.; Dubuc, J.; Meier, S.; Heuwieser, W.; Arlt, S.; Gilbert, R. O.; McDougall, S. (July 2014). "Invited review: Systematic review of diagnostic tests for reproductive-tract infection and inflammation in dairy cows". Journal of Dairy Science. 97 (7): 3983–3999. doi:10.3168/jds.2013-7450. ISSN 1525-3198. PMID 24835959.