Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Samatata

View on Wikipedia

Samataṭa (Brahmi script: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() sa-ma-ta-ṭa) was an ancient geopolitical division of Bengal in the eastern Indian subcontinent. The Greco-Roman account of Sounagoura is linked to the kingdom of Samatata. Its territory corresponded to much of present-day eastern and southern Bangladesh (particularly Dhaka division, Barisal division, Sylhet Division, Khulna Division and Chittagong Division). The area covers the trans-Meghna part of the Bengal delta. It was a center of Buddhist civilisation before the resurgence of Hinduism, and Muslim conquest in the region.

sa-ma-ta-ṭa) was an ancient geopolitical division of Bengal in the eastern Indian subcontinent. The Greco-Roman account of Sounagoura is linked to the kingdom of Samatata. Its territory corresponded to much of present-day eastern and southern Bangladesh (particularly Dhaka division, Barisal division, Sylhet Division, Khulna Division and Chittagong Division). The area covers the trans-Meghna part of the Bengal delta. It was a center of Buddhist civilisation before the resurgence of Hinduism, and Muslim conquest in the region.

Key Information

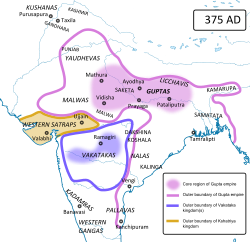

Archaeological evidence in the Wari-Bateshwar ruins, particularly punch-marked coins, indicate that Samataṭa was probably a province of the Mauryan Empire. The region attained a distinct Buddhist identity following the collapse of Mauryan rule. The Allahabad pillar inscriptions of the Indian emperor Samudragupta is the earliest reference of Samataṭa in which it is described as a tributary state.

Samataṭa gained prominence as an important region of Bengal during the reigns of the Gauda Kingdom, Khadga dynasty, First Deva dynasty,[5][4] Chandra dynasty and Varman dynasty between the 6th and 11th centuries. During this period, the rulers of Samataṭa also reigned over parts of Arakan, Tripura and Kamarupa. Chinese travellers provide an elaborate description of the region in the 7th century. According to Alexander Cunningham, Jessore was the capital of Samatata.[6] Xuanzang of China visited the region in 630s.

Records of the Sena dynasty include mention of Samataṭa as a haven for Sena kings who escaped the Muslim conquest of western Bengal during the 13th century. The area was eventually absorbed by the forces of the Delhi Sultanate.

Names

[edit]Samataṭa has been described by various similar names, including Samatat/Samata/Saknat/Sankat/Sankanat.In Sanskrit, sama means equal and taṭa means coast or shore.

Geography

[edit]On the basis of the evidence provided by inscriptions, Chinese writings, and archaeological evidence, it can be deduced that Samatata covered the trans-Meghna territories. It included areas along the banks of the Meghna River and its tributaries; including the modern Bangladeshi districts of Sylhet, Maulvi Bazar, Habiganj, Sunamganj, Narsingdi, Narayanganj, Dhaka, Munshiganj, Brahmanbaria, Chandpur, Comilla, Noakhali, Feni and Lakshmipur. It included the Bangladeshi Channel Islands of Hatia and Sandwip; as well as the islands of Bhola, Maheshkhali, Kutubdia and St. Martin's.[citation needed] It included parts of Tripura (in present-day Northeast India), Bangladesh's Chittagong and Cox's Bazar districts; and northern Arakan (present-day Rakhine State, Myanmar). Samatata's erstwhile neighbours included the geopolitical divisions of Vanga (Southwest Bengal), Pundravardhana (North Bengal), and parts of Kamarupa (historical Assam).

History

[edit]The Roman geographer Ptolemy wrote about a trading post called Souanagoura in the eastern part of the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta.[8] The archaeologist Sufi Mostafizur Rahman believes the riverside citadel in the Wari-Bateshwar ruins was the city-state of Sounagoura.[9] According to Ptolemy, Sounagoura was located on the bank of the Brahmaputra River and was an "emporium", which is a term used by the Roman Empire to refer to a trading colony set up by Roman merchants. The Brahmaputra River flowed down from the Himalayas and to the east of Wari-Bateshwar before joining the Meghna River on its way to the Bay of Bengal. Ptolemy's account places Sounagoura near the old course of the Brahmaputra River. The Brahmaputra changed its course following an earthquake in 1783. Excavations in Wari-Bateshwar reveal an urban and monetary civilisation since the pre-Mauryan period.[10][11] Archaeologist and historian Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti also considers Wari-Bateshwar to be a part of the trans-Meghna region.[12][13] In a book edited by Patrick Olivelle, Chakrabarti states "It appears that Wari-Bateshwar belongs to the Samatata tract. Till now this is the only early historic site reported from this tract, but the very fact that it existed as early as the mid-fifth century BCE in this part of Bangladesh shows the geographical unit of Samatata, although inscriptionally documented in the fourth century CE, has a much earlier antiquity which touches the Mahajanapada period. Secondly, on the basis of the fact that Wari-Bateshwar is a fortified settlement, we argue that in addition to its character as a manufacturing and trading center, it was also an administrative center and most likely to be the ancient capital of the Samatata region".[14]

Soon after the death of emperor Ashoka, the Mauryan Empire declined and the eastern part of Bengal became the state of Samatata.[15] The rulers of the erstwhile state remain unknown. During the Gupta Empire, the Indian emperor Samudragupta recorded Samatata as a "frontier kingdom" which paid an annual tribute. This was recorded by Samudragupta's inscription on the Allahabad pillar, which states the following in lines 22–23.

) in later Brahmi script, in the Allahabad Pillar inscription of Samudragupta (350–375 CE).[16]

) in later Brahmi script, in the Allahabad Pillar inscription of Samudragupta (350–375 CE).[16]"Samudragupta, whose formidable rule was propitiated with the payment of all tributes, execution of orders and visits (to his court) for obeisance by such frontier rulers as those of Samataṭa, Ḍavāka, Kāmarūpa, Nēpāla, and Kartṛipura, and, by the Mālavas, Ārjunāyanas, Yaudhēyas, Mādrakas, Ābhīras, Prārjunas, Sanakānīkas, Kākas, Kharaparikas and other nations"

— Lines 22–23 of the Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta (r.c.350-375 CE).[16]

Samatata's recorded independent dynasties are the Gauda, Bhadra,[17] Khadga, Deva,[4][5] Chandra and Varman dynasties. The Khadgas were originally from Vanga but later conquered Samatata. A Chinese account of the Khadga king Rajabhatta places the royal capital of Karmanta-vasaka (identified with Barakamata village in Comilla) in Samatata.[18] After the Khadgas, the Devas gained power and started ruling over the kingdom from their capital Devaparvata (identified with Kotbari area in Mainamati near Comilla City. The Devas were devout Buddhists and constructed many temples, muras and vihara in Devaparvata including Shalban Vihara, Ananda Vihara, Bhoj Vihara, Itakhola Mura, Rupban Mura etc. They were succeeded by the Chandras, who were also an important Buddhist dynasty and ruled over Samatata, Vanga and Arakan (Burma). The Chandras were powerful enough to withstand the Pala Empire to the northwest.

Samatata was a flourishing center of Buddhism. As devout Tantric Buddhists, the Devas and the Chandras established their religious and administrative center in the archaeological site of Mainamati.[19] The Chandras were also notable for seafaring networks. The ports of Samatata were linked to ports in present-day Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam. The Chandras may have played a role in the spread of Mahayana Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Bronze sculptures may have been imported by Java from Samatata. The Srivijaya Empire's embassies to the Pala court may have passed through the ports of southeastern Bengal. Arab accounts also note trade routes with Orissa and Sri Lanka. 10th century shipwrecks in Indonesia provide evidence of maritime contact with Bengal.[20]

Samatata continued to play an important role in the history of the region until the 13th century. During the Muslim conquest of Bengal, Samatata served as the last refuge of the Sena kings.[18] Its decline coincided with the decline of Buddhism in India.

Silk Road and Chinese accounts

[edit]

| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

The Chinese pilgrim and traveller Xuanzang, who made his way across the Silk Road from northern China into the subcontinent through present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh; visited Samatata at the end of his journey in ancient India. He called the kingdom San-mo-ta-ch'a. Xuanzang found 30 Buddhist monasteries with 2000 monks in Samatata. Xuanzang also provided descriptions of the regions' geography, including the harbour of Chittagong and nearby Burmese kingdoms. A later Chinese traveller Yijing observed that there were 4000 Buddhist monks and nuns in Samatata.[21][22][23][24]

Epigraphy and archaeology

[edit]Epigraphs

[edit]- Allahabad pillar inscription of the Gupta dynasty (4th century)

- Copperplate of Shridharana Rata

- Khadga copperplates

- Chandra copperplates

- Mehar copperplate of Damodaradeva

Associated archaeological sites

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Samatata coin". British Museum.

- ^ Singer, Noel F. (2008). Vaishali and the Indianization of Arakan. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-313-0405-1.

- ^ Prasad, Bindeshwari (1977). Dynastic History of Magadha. p. 136.

- ^ a b c Sein, U. Aung Kyaw (May 2011). Vesāli: Evidences of Early Historical City in Rakhine Region (MA). University of Yangoon.

- ^ a b Singer, Noel F. (2008). Vaishali and the Indianization of Arakan. New Delhi: APH Publishing Corp. ISBN 978-81-313-0405-1. OCLC 244247519.

- ^ Cunningham, Alexander (1871). Ancient Geography of India. London: Trübner & Co. pp. 501–503.

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 145, map XIV.1 (d). ISBN 0226742210. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ "First, in his list of towns in transgangetic India Ptolemy mentions a place called Souanagoura which has been identified with modern Sonargaon" Excavation at Wari-Bateshwar: A Preliminary Study, Enamul Haque – 2001

- ^ Kamrul Hasan Khan, back from Wari-Bateswar (1 April 2007). "The Daily Star Web Edition Vol. 5 Num 1008". Archive.thedailystar.net. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "A Family's Passion – Archaeology Magazine". Archaeology.org. Archived from the original on 24 November 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Shahnaj Husne Jahan X close (2010). "Archaeology of Wari-Bateshwar". Ancient Asia. 2: 135. doi:10.5334/aa.10210.

- ^ Dilip K. Chakrabarti (1 June 1997). Colonial Indology: sociopolitics of the ancient Indian past. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-0750-9.

- ^ Dilip K. Chakrabarti (1998). The issues in East Indian archaeology. Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 978-81-215-0804-9.

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (13 July 2006). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1.

- ^ Douglas A. Phillips; Charles F. Gritzner (2007). Bangladesh. Infobase Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4381-0485-0.

- ^ a b Fleet, John Faithfull (1888). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol. 3. pp. 6–10.

- ^ Chakrabarti, Amita (1991). History of Bengal, C. A.D. 550 to C. A.D. 750. University of Burdwan. p. 122.

- ^ a b Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Samatata". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 30 October 2025.

- ^ Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Chandra Dynasty, The". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 30 October 2025.

- ^ Ghosh, Suchandra (2013). "Locating South Eastern Bengal in the Buddhist Network of Bay of Bengal (C. 7th Century CE–13th Century CE)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 74: 148–153. JSTOR 44158810.

- ^ Lal Mani Joshi (1977). Studies in the Buddhistic Culture of India During the Seventh and Eighth Centuries A.D. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 35. ISBN 978-81-208-0281-0. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Xuanzang (1906). Si-yu-ki: Ta-T'ang-si-yu-ki. Books 6-12. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Company.

- ^ Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Chinese Accounts". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 30 October 2025.

- ^ Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Hiuen-Tsang". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 30 October 2025.

![Samatata coinage of Vira Jadamarah, imitative of the Kushan coinage of Kanishka I. The text of the legend is a meaningless imitation, c. 2nd–3rd century CE.[1] of](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/33/Bengal._Samatata._Coin_of_Vira_Jadamarah_imitative_of_Kushan_coinage_of_Kanishka_I._Circa_2nd-3rd_century_CE.jpg/330px-Bengal._Samatata._Coin_of_Vira_Jadamarah_imitative_of_Kushan_coinage_of_Kanishka_I._Circa_2nd-3rd_century_CE.jpg)