Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Baro-Bhuyan

View on Wikipedia

| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Assam |

|---|

|

| Categories |

The Baro-Bhuyans (or Baro-Bhuyan Raj; also Baro-Bhuians and Baro-Bhuiyans) were confederacies of soldier-landowners in Assam and Bengal in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period. The confederacies consisted of loosely independent entities, each led by a warrior chief or a landlord.[1] The tradition of Baro-Bhuyan is peculiar to both Assam and Bengal[2] and differ from the tradition of Bhuihar of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar[3]—in Assam this phenomenon came into prominence in the 13th century when they resisted the invasion of Ghiyasuddin Iwaj Shah[4] and in Bengal when they resisted Mughal rule in the 16th century.[5]

Baro denotes the number twelve, but in general there were more than twelve chiefs or landlords, and the word baro meant many.[6] Thus, Bhuyan-raj denoted individual Bhuyanship, whereas Baro-Bhuyan denoted temporary confederacies that they formed.[1] In times of aggression by external powers, they generally cooperated in defending and expelling the aggressor. In times of peace, they maintained their respective sovereignty. In the presence of a strong king, they offered their allegiance.[7] In general each of them were in control of a group of villages, called cakala, and the more powerful among them called themselves raja.[8] The rulers of the Bhuyanships belonged to different ethnic, religious or social backgrounds.[9][10]

In 13th century Brahmaputra Valley the system of Baro-Bhuyan Raj (confederacy) was formed from the petty chieftains—the remaining fragments of the erstwhile Kamarupa state.[1][11] They often resisted foreign invasions (Ghiyasuddin Iwaj Shah in the 13th century), removed foreign rule (Hussain Shah in the 16th century) and sometimes usurped state power (Arimatta in the 14th century). They occupied the region west of the Kachari kingdom in the south bank of the Brahmaputra river, and west of the Chutiya kingdom in the north bank. These included areas of Nagaon, Darrang and Sonitpur districts. Subsequently, the Baro Bhuyan rule ended in the 16th century as they were squeezed between the Kachari kingdom and the Kamata kingdom in the west and were slowly overpowered by the expanding Ahom kingdom in the east.

In Bengal, the most prominent Baro-Bhuyan confederacy was led by Isa Khan of Sonargaon in the 16th century, which emerged during the disintegration of the Bengal Sultanate in the region, as a resistance to the Mughal expansion.[12] They carved the land of Bhati and other areas of Bengal into twelve administrative units or Dwadas Bangla.[13] The Baro-Bhuyans gradually succumbed to the Mughal dominance and eventually lost control during the reign of emperor Jahangir, under the leadership of Islam Khan I, the governor of Bengal Subah.[14]

Baro-Bhuyans of Assam

[edit]Epigraphic sources indicate that the Kamarupa state had entered a state of fragmentation in the 9th century[15] when the tradition of granting away police, revenue and administrative rights to the donee of lands became common.[16] This led to the creation of a class of landed intermediary between the king and his subjects—the members of which held central administrative offices, maintained economic and administrative links with in their own domain[17] and propagated Indo-Aryan culture.[18] This gave rise to the condition that individual domains were self-administered, economically self-sufficient and capable of surviving the fragmentation of central authority,[19] when the Kamarupa kingdom finally collapsed in the 12th century.

Amalendu Guha claims that the Baro-Bhuyan emerged in the 13th century from the fragmented remains of the Kamarupa chieftains.[1] Nevertheless, not all local Kamarupa administrators (samanta) became Bhuyans and many were later-day migrant adventurers from North India.[20] Though there exists many legendary accounts of the origin of the Baro Bhuyan these accounts are often vague and contradictory.[21]

The Adi Bhuyan group

[edit]This original group is often referred to as the Adi Bhuyan, or the progenitor Bhuyans. The Adi-charita written in the late 17th century is the only manuscript which mentions the Adi-Bhuyan group.[22] However, Maheswar Neog has called the account as spurious or fabricated.[23]

Nevertheless, their presence is recorded in the Ahom Buranjis, where it is recorded that they were instrumental in ending the rule of the Kachari kingdom.[24] As a reward, the Ahom king Suhungmung (1497–1539) settled these Bhuyans (originally living in Rowta-Temoni) in Kalabari, Gohpur, Kalangpur and Narayanpur as tributary feudal lords.[25] Over time, these Bhuyans grew very powerful but they were later subjugated by the Ahom king Jayadhwaj Singha. The Saru Baro Bhuyan is a branch of the Bar Baro Bhuyan that split and went west.

By the mid 16th century, all the Adi Bhuyans power was crushed, and they remained satisfied with what service they could render to the Ahom state as Baruwas or Phukans, Tamulis or Pachanis. During the first expedition of Chilarai against the Ahom kingdom, they aligned with the Ahoms (which Chilarai lost), but during the second expedition they aligned with the Koches (which Chilarai won). Chilarai appointed Uzir Bamun, Tapashi Laskar and Malamulya Laskar as Rajkhowas in Uttarkula after he annexed the territories up to Subansiri River in 1563 AD.[26] This group was finally subjugated by Prataap Singha in 1623, who relocated them to the south bank of the Brahmaputra.[27] The Saru Bhuyans, who had moved west after the conflict with the Bor Baro-Bhuyans trace the genealogy of Candivara to Kanvajara, the eldest son of Sumanta, but this is not given credence.

The Later group

[edit]The later Baro-Bhuyans had ensconced themselves between the Kachari kingdom in the east and the Kamata kingdom in the west on the south bank of the Brahmaputra River. According to Neog, the leader (shiromani) of the group, Chandivara, was originally a ruler of Kannauj, who had to flee due to Firuz Shah Tughlaq's 1353 campaign against Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah and reached Gauda, the domain of Dharmanarayana.[28] As a result of a treaty between Dharmanarayana and Durlabhnarayana of Kamata kingdom, a group of seven Kayastha and seven Brahmin families led by Candivara was transferred to Langamaguri, a few miles north of present-day Guwahati.[29] During the harvesting season in Lengamaguri, the Bhutiyas attacked and looted the country and in one instance the Bhutiyas captured Rajadhara, the son of Candivara. Candivara chased the Bhutiyas as far as Daimara between Maguri (near Changsari town) and Dewangiri (in Bhutan), killed few of them and released his son from captivity. In next four or five years, the people of Lengamaguri finding that Bhutiyas were planning an attack in retaliation decided to hand over Candivara as the person responsible for the massacre of the Bhutiyas.[30] The Bhutiyas chased Candivara as far as Rauta (in present-day Udalguri district) but had to suffer defeat at the hands of the Baro-Bhuyans.[31] Candivara and his group in search of a safe haven did not stay in Lengamaguri for long and moved soon to Bordowa in present-day Nagaon district with the support of Durlabhnarayana.[29] Among the descendants of Candivara was Srimanta Sankardeva.

After the death of Candivara, Rajadhara became the Baro-Bhuyan. A second group of five Bhuyans joined the Candivara group later.[29] In due course, members of these Bhuyans became powerful. Alauddin Husain Shah, who ended the Khen dynasty by displacing Nilambar in 1498, extended his rule up to the Barnadi river by defeating Harup Narayan who was a descendant of Gandharva-raya, a Bhuyan from the second group established by Durlabhnarayana at Bausi (Chota raja of Bausi), among others.[32] The Baro-Bhuyans retaliated and were instrumental in ending the rule of Alauddin Husain Shah via his son Shahzada Danyal. But very soon, the rise of Biswa Singha of the Koch dynasty in Kamata destroyed their hold in Kamrup[33] and squeezed those in the Nagaon region against the Kacharis to their east. They had to relocate to the north bank of the Brahmaputra in the first quarter of the 16th century, to a region west of the Bor Baro-Bhuyan group. The increasing Koch and Ahom conflicts further ate away at their independence and sovereignty.

Baro-Bhuiyans of Bengal

[edit]At the end of the Karrani Dynasty (1564–1575), the nobles of Bengal became fiercely independent. Sulaiman Khan Karrani carved out an independent principality in the Bhati region comprising a part of greater Dhaka district and parts of Mymensingh district. During that period Taj Khan Karrani and another Afghan chieftain helped Isa Khan to obtain an estate in Sonargaon and Mymensingh in 1564. By winning the grace of the Afghan chieftain, Isa Khan gradually increased his strength and status and by 1571, he had become the ruler of Bhati.[34]

Bhati region

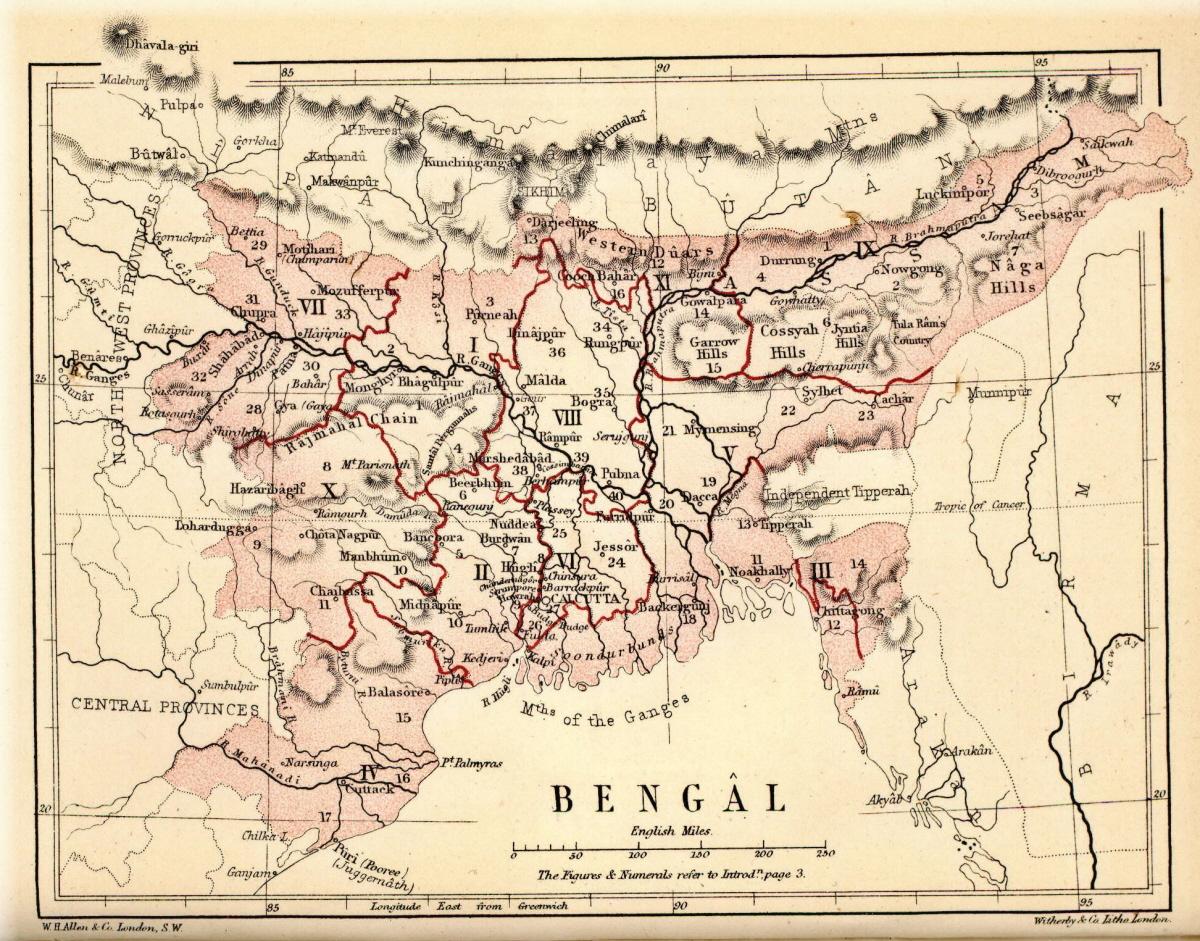

[edit]Mughal histories, mainly the Akbarnama, the Ain-i-Akbari and the Baharistan-i-Ghaibi refers to the low-lying regions of Bengal as Bhati.

This region includes the Bhagirathi to the Meghna River is Bhati, while others include Hijli, Jessore, Chandradwip and Barisal Division in Bhati. Keeping in view the theatre of warfare between the Baro-Bhuiyans and the Mughals, the Baharistan-i-Ghaibi mentions the limits of the area bounded by the Ichamati River in the west, the Ganges in the south, the Tripura to the east; Alapsingh pargana (in present Mymensingh District) and Baniachang (in greater Sylhet) in the north. The Baro-Bhuiyans rose to power in this region and put up resistance to the Mughals, until Islam Khan Chisti made them submit in the reign of Jahangir.[12]

Isa Khan

[edit]Isa Khan was the leader of the Baro Bhuiyans (twelve landlords) and a zamindar of the Bhati region in medieval Bengal. Throughout his reign he resisted the Mughal Empire invasion. It was only after his death, the region went totally under the Mughal emperors.[12]

The Jesuit mission who was sent to Bengal managed to identify that 3 of the chieftains were Hindus, they were Kandarpa Narayan Basu of Chandradwip, Bakla (Barisal), Kedar Ray of Bikrampur,[35] and Pratapaditya of Jessore, while the rest were Muslims during Isa Khan's rule. Nalini Kanta Bhattasali affirms that there were more than twelve Bhuiyans, with the word baro signifying a large number.[36][37]

Notable persons

[edit]- Musa Khan of Sonargaon; inheritor of Isa Khan

- Khwaja Usman of Bokainagar, Mymensingh and later Uhar, Sylhet

- Bayazid of Sylhet[38]

- Majlis Qutb of Fatehabad

- Pitambar and Ananta of Chila-Jowar, Rajshahi

- Kedar Ray of Bikrampur[39]

- Bahadur Khan of Hijli[40]

- Pratapaditya of Jessore[41]

- Surendranath Sur of Khardah

- Bir Hambir of Bishnupur

- Bhavashankari of Bhurishrestha, and later Hoogly

- Fazal Gazi of Bhawal

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d "In the 13th century, the Indo-Aryan culture still dominated the lives of a major section of the population in the central plains of the Brahmaputra Valley. However, nothing was left of the ancient state of Kamarupa at that juncture, except for what fragments remained of it in the form of petty chiefdoms. The petty chiefs were called bhuyan many of whom were migrant adventurers from North India. The rule by a bhuyan was called bhuyan-raj and their temporary confederacies were known as bara-bhuyan raj."(Guha 1983:10)

- ^ "The tradition of Bara Bhuyan is peculiarly common to both Assam and Bengal." (Neog 1992:63)

- ^ "[T]he Bhuyans of Assam have nothing to do with Bhuihars or Babhans of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar..." (Neog 1992:63)

- ^ "The Bara Bhuyans of Kamarupa played a similar role in the country's history round about the thirteenth century...Jadunath Sarkar holds that Husamuddin Iwaz (c. 1213–1227) reduced some of the Barabhuyans to submission when he attacked Kamarupa." (Neog 1992:63–64)

- ^ "Some of the Bara Bhuyans of Bengal are mentioned in the Akbar-namah and Ain-i-Akbari so that the institution seems to have been in existence even before the times of Akbar." (Neog 1992:63)

- ^ (Neog 1980:49f)

- ^ (Neog 1980, p. 49)

- ^ (Neog 1980, p. 48)

- ^ "The territories under the Bhuyans, a growing landlord class, mostly belonging to the Brahmanas and Kayasthas, in the middle of the valley on both banks of the Brahmaputra"(Sarma 2010:243)

- ^ "It is usually believed that the Bhuyans constituted a Hindu caste. But the Darrang Raj Vamshavali, as well as in Persian sources like the Akbarnama and the Ain-i-Akbari, there are references to Muslim Bhuyans as well. This confirms that the Bhuyans were a class rather than a caste."(Nath 1989:21)

- ^ "The Karatoya on the western border is a well-known river now flowing through the Jalpaiguri District of West Bengal and the Rangpur and Bogra Districts of Bangladesh while the junction of the Brahmaputra and the Laksha (modern Lakhya) at the southern boundary now stands near the border between near the border between the Dacca and Mymensingh Districts of Bangladesh." (Sircar 1990:63)

- ^ a b c Abdul Karim (2012). "Bara Bhuiyans, The". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 13 February 2026.

- ^ Akbarnama, Volume III, Page 647

- ^ "History". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

Shah-i-Bangalah, Shah-i-Bangaliyan and Sultan-i-Bangalah

- ^ "We, incidentally, do not deny that some kind of fragmentation had taken place in Assam but would argue that the process set in quite early, in the 9th century, in fact. We get a good deal of information on this point from the epigraphic records." (Lahiri 1984:61)

- ^ "The parcellization of political power was reinforced by the large scale donations of land which comprise the most important economic trend in this period. Although the first land grant from Assam was issued in the 5th century A.D. (the Nagajari Khanikargaon fragmentary stone inscription), from the 9th century onwards, police, revenue and administrative rights were granted away along with large plots of land by reigning monarchs to brahmins; this trend continued right till the end of the 12th century. The Nowgong plates of Balavarman III (end of the 9th century) are fairly illustrative of this point." (Lahiri 1984, p. 62)

- ^ "On the one hand, they were linked through economic ties with the common people--they were the beneficiaries of large scale land donations, plots, sometimes villages, which very often had to be cultivated by others." (Lahiri 1984:63)

- ^ The importance of this class of landed intermediaries in pre-Ahom Assam is worth mentioning. That significant links existed between the brahmins and the common people is evident from the penetration of Sanskrit culture to the grass roots level." (Lahiri 1984:62)

- ^ "The basic point we are trying to make is this: if the brahmin landed intermediaries by the 13th century are vested with political, administrative and economic power, if the village has emerged as a self-sufficient axis, this entire structure would only be marginally affected by fragmentation at the central level." (Lahiri 1984:63)

- ^ "Not all of them were transformed into local bhuyan chiefs, since many of the bhuyans were known to be migrant adventurers of high caste, coming from North India after the fall of Kanauj to the Turko-Afghans." (Guha 1984:77)

- ^ (Neog 1980:48)

- ^ Neog, Maheswar, Early History of the Vaishnavite Faith and Movement in Assam, p. 29, It is supposed to have been written in 1586 saka (1664 AD).

- ^ Maheswar Neog states that the Adi-cwita, ascribed to Madhavadeva, has created much ill feeling among the Vaisnavas of Assam, and has been denounced by the more considerate section of sattra pontiffs and literary men alike.

- ^ "On the behalf of the Ahom king, they fought with and killed , the Kachari and Dhirnarayana, the Chutiya king"(Neog 1980:53)

- ^ (Neog 1980:53)

- ^ History of the Koch Kingdom, c. 1515–1615, p.58.

- ^ (Neog 1980, p. 58)

- ^ (Neog 1980, p. 41)

- ^ a b c (Neog 1980, p. 51)

- ^ (Neog 1980:65)

- ^ (Neog 1980:65–66)

- ^ (Neog 1980, pp. 53–54)

- ^ (Neog 1980, pp. 54–55)

- ^ "A tale of Baro-Bhuiyans". The Independent. Dhaka. 5 December 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Ahmed, Salahuddin (2004). Bangladesh: Past and Present. APH Publishing. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-81-7648-469-5.

- ^ Eaton, Richard Maxwell (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9.

- ^ Bhattasali, Nalini Kanta (1928). "Bengal Chiefs' Struggle for independence in the reign of Akbar & Jahangir". Bengal, Past & Present. 35. Calcutta Historical Society.

- ^ Saha, Sanghamitra (1998). A handbook of West Bengal. International School of Dravidian Linguistics. p. 110. ISBN 9788185692241.

- ^ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal. 1939.

- ^ Khan, Muazzam Hussain (2012). "Bahadur Khan". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 13 February 2026.

- ^ Nagendra Nath Ray (1929). Pratapaditya. B. Bhattacharyya at the Sree Bhagabat Press.

References

[edit]- Guha, Amalendu (December 1983). "The Ahom Political System: An Enquiry into the State Formation Process in Medieval Assam (1228–1714)". Social Scientist. 11 (12): 3–34. doi:10.2307/3516963. JSTOR 3516963. Archived from the original on 6 July 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Guha, Amalendu (June 1984). "The Ahom Political System: An Enquiry into the State Formation Process in Medieval Assam: A Reply". Social Scientist. 12 (6): 70–77. doi:10.2307/3517005. JSTOR 3517005.

- Lahiri, Nayanjot (June 1984). "The Pre-Ahom Roots of Medieval Assam". Social Scientist. 12 (6): 60–69. doi:10.2307/3517004. JSTOR 3517004.

- Nath, D (1989), History of the Koch Kingdom: 1515–1615, Delhi: Mittal Publications

- Neog, M (1992), "Origin of the Baro-Bhuyans", in Barpujari, H. K. (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, vol. 2, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board, pp. 62–66

- Neog, M (1980), Early History of the Vaisnava Faith and Movement in Assam, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass

- Sircar, D C (1990), "Pragjyotisha-Kamarupa", in Barpujari, H K (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, vol. I, Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam, pp. 59–78

- Sarma, Diganta Kumar (2010), "Religious Transformation of the Ahom Rulers in the Crossroad of Making a Unified Society", Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 71: 243–47, JSTOR 44147491