Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Perpetual Union

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| American Revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

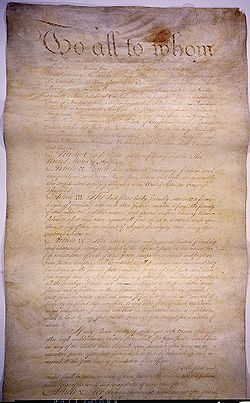

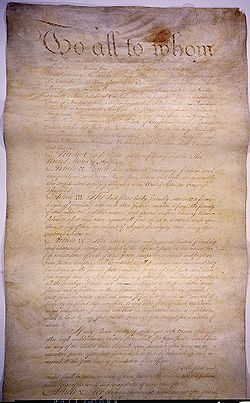

The Perpetual Union is a feature of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, which established the United States of America as a political entity and, under later constitutional law, means that U.S. states are not permitted to withdraw from the Union.

The Articles of Confederation detailed the rights, responsibilities, and powers of the newly independent United States of America. However, the Articles provided a system of government considered too weak by the nationalists led by George Washington.[1] It was superseded in 1789 by the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, a document written and approved at the 1787 Constitutional Convention.

Historical origins

[edit]The concept of a Union of the British American States originated gradually during the 1770s as the struggle for independence unfolded. In his first inaugural address on March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln stated:

The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed, in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774. It was matured and continued by the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It was further matured, and the faith of all the then thirteen States expressly plighted and engaged that it should be perpetual, by the Articles of Confederation in 1778. And finally, in 1787, one of the declared objects for ordaining and establishing the Constitution was to form a more perfect Union.[2]

A significant step was taken on June 12, 1776, when the Second Continental Congress approved the drafting of the Articles of Confederation, following a similar approval to draft the Declaration of Independence on June 11. The purpose of the former document was not only to define the relationship among the new states but also to stipulate the permanent nature of the new union. Accordingly, Article XIII states that the Union "shall be perpetual". While the process to ratify the Articles began in 1777, the Union only became a legal entity in 1781 when all states had ratified the agreement. The Second Continental Congress approved the Articles for ratification by the sovereign States on November 15, 1777, which occurred during the period from July 1778 to March 1781.

The 13th ratification by Maryland was delayed for several years due to conflict of interest with some other states, including the western land claims of Virginia. After Virginia passed a law on January 2, 1781, relinquishing the claims, the path forward was cleared. On February 2, 1781, the Maryland state legislature in Annapolis passed the Act to ratify and on March 1, 1781, the Maryland delegates to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia formally signed the agreement. Maryland's final ratification of the Articles of Confederation and perpetual Union established the requisite unanimous consent for the legal creation of the United States of America.

Significance

[edit]From the start the Union has carried with it importance in national affairs. There was a sense of urgency in completing the legal Union during the American Revolutionary War. Maryland's ratification act stated, "[I]t hath been said that the common enemy is encouraged by this State not acceding to the Confederation, to hope that the union of the sister states may be dissolved".[3] The nature of the Union was hotly debated during a period lasting from the 1830s through its climax during the American Civil War. During the war, the remaining U.S. states that were not joining the breakaway Confederates were called "the Union".

Constitutional basis

[edit]| This article is part of a series on the |

| United States Continental Congress |

|---|

|

| Predecessors |

| First Continental Congress |

| Second Continental Congress |

| Congress of the Confederation |

| Members |

| Related |

|

|

When the United States Constitution replaced the Articles, nothing in it expressly stated that the Union is perpetual. Even after the Civil War, which had been fought by the U.S. to prevent eleven of the southern slave states from leaving the Union, some still questioned whether any such inviolability survived after the U.S. Constitution replaced the Articles. This uncertainty also stems from the fact that the Constitution was not ratified unanimously before going into effect, as required by the Articles (two states, North Carolina and Rhode Island, had not ratified when George Washington was sworn in as the first U.S. president). The United States Supreme Court ruled on the issue in the 1869 Texas v. White case.[4] In that case, the court ruled that the drafters intended the perpetuity of the Union to survive:

By [the Articles of Confederation], the Union was solemnly declared to "be perpetual." And when these Articles were found to be inadequate to the exigencies of the country, the Constitution was ordained "to form a more perfect Union." It is difficult to convey the idea of indissoluble unity more clearly than by these words. What can be indissoluble if a perpetual Union, made more perfect, is not?. . . When, therefore, [a state] became one of the United States, she entered into an indissoluble relation. All the obligations of perpetual union, and all the guaranties of republican government in the Union, attached at once to the State. The act which consummated her admission into the Union was something more than a compact; it was the incorporation of a new member into the political body. And it was final.

— U.S. Supreme Court, Texas v. White (1869).[4]

During the ratification of the Constitution, ratifications by New York, Virginia and Rhode Island included language that reserved the right of those states to exit the U.S. federal system if they felt "harmed" by the arrangement. In Virginia's ratification the reservation is stated thus; "…the People of Virginia declare and make known that the powers granted under the Constitution being derived from the People of the United States may be resumed by them whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression …"[5]

However, in a 1788 letter to Alexander Hamilton, James Madison disapproved of the language, and stated in regards to it that:

My opinion is that a reservation of a right to withdraw ... is a conditional ratification … Compacts must be reciprocal … The Constitution requires an adoption in toto, and for ever. It has been so adopted by the other States.

Hamilton and John Jay agreed with Madison's view, reserving "a right to withdraw [was] inconsistent with the Constitution, and was no ratification."[8] The New York convention ultimately ratified the Constitution without including the "right to withdraw" language proposed by the anti-federalists.[8] Gouverneur Morris, often called the "Penman of the Constitution," by contrast argued during the War of 1812 that States could secede under certain conditions.[9]

In his first inaugural address, George Washington referred to an "indissoluble union", and in his Farewell Address to the country, telling Americans that they should maintain "the security of their union and the advancement of their happiness."[10] In his farewell address, Washington stated that the union of states was "your union and brotherly affection may be perpetual", and in urging Americans to maintain it, stated that "you should properly estimate the immense value of your national Union to your collective and individual happiness."[11] Patrick Henry, shortly before his death, urged Americans not to "split into factions which must destroy that union upon which our existence hangs."[12]

Conservative Constitutional scholar Kevin Gutzman took a contrarian approach, arguing that in the 1700s some treaties were purported to be "perpetual" but could still be abrogated by either side, and thus that "perpetual" only meant that there was no built-in sunset provision.[13][14] For example, the Treaty of Paris called for a "perpetual peace" between Great Britain and the United States,[15] but the two nations warred again in the War of 1812. Gutzman's position received criticism for ignoring historical evidence surrounding the drafting of the constitution, and for being overly defensive of the Confederacy.[16]

More recently in 2006, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia stated, "If there was any constitutional issue resolved by the Civil War, it is that there is no right to secede."[17]

Similar principles

[edit]The concept of a perpetual union appeared earlier in European political thought. In 1532, Francis I of France signed the Treaty of Perpetual Union (fr. Traité d'Union Perpétuelle), which pledged the freedom and privileges of the Duchy of Brittany within the Kingdom of France.[18] In 1713, Charles de Saint-Pierre presented a plan "A project for settling an everlasting peace in Europe," where in it is stated in Article 1:

There shall be from this day following a Society, a permanent and perpetual Union, between the Sovereigns subscribed.[19]

By itself the word perpetual appears much earlier in the history of political thought. In January 44 B.C., Denarii coins were struck with the image of Julius Caesar and the Latin inscription "Caesar Dic(tator in) Perpetuo".[20]

The contrast can be seen in the superficially similar corollary in the Union of Scotland and England, set out in section 1 of the Act of Union 1707. The section states "that the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England shall upon the first day of May next ensuing the date hereof and forever after be United into One Kingdom by the Name of Great Britain"[21] The Act of Union 1801, uniting Great Britain and Ireland was set out in similar terms, but the Irish Free State, later the Republic of Ireland did leave the Union in 1922. The doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty in the United Kingdom prevented the creation of a 'greater law' to entrench the Act of Union, a legal doctrine confirmed in the aftermath of Brexit in re Jim Allister[22] when Northern Ireland Unionist politicians attempted to judicially review the Northern Ireland Protocol as breaking the Act and the Treaty of Union. The court concluded that while the Protocol did repeal provisions of the Act by implication, Parliament was entirely free to do so as even the Act of Union had no special entrenched status.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Edward J. Larson, George Washington, Nationalist (U of Virginia Press, 2016) ch. 1.

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham (March 4, 1861). "Abraham Lincoln's First Inaugural Address on March 4, 1861". AMDOCS: Documents for the Study of American History. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ^ Papers of the Continental Congress, No. 70, folio 453 and No. 9, History of the Confederation

- ^ a b 74 U.S. 700 (1869)

- ^ "Ratification of the Constitution by the State of Virginia". Virginia. June 26, 1788. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ Madison, James (July 20, 1788). "Letter to Alexander Hamilton". Archived from the original on April 12, 2001. Retrieved April 12, 2001.

- ^ Marshall L. DeRosa, ed. (1998). "Preserve the Union". The Politics of Dissolution. Transaction Publishers. pp. 58–59. ISBN 9781412838375. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Amar, Akhil Reed (September 19, 2005). "Conventional Wisdom". New York Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2015. Also located here.

- ^ Forrest McDonald, Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas: 1985, 281.

- ^ Washington, George (1789). "First Inaugural Address".

- ^ Washington, George (1796). "Washington's Farewell Address".

- ^ Henry, William Wirt (1891). Patrick Henry: Life, Correspondences and Speeches. Vol. 2. New York, Charles Scribner's sons. pp. 609–610.

- ^ Kevin Gutzman, The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Constitution, Regency Publishing, Inc., Washington D.C.: 2007, 12.

- ^ "Kevin Gutzman, Author at The Imaginative Conservative". The Imaginative Conservative.

- ^ Treaty of Paris (1783), http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/paris.asp

- ^ "Whistling Dixie". Claremont Review of Books. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Letter dated October 31, 2006, to Daniel Turkewitz. http://www.newyorkpersonalinjuryattorneyblog.com/uploaded_images/Scalia-Turkewitz-Letter-763174.jpg Archived July 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "History of Brittany". Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ^ Chris Brown; Terry Nardin; Nicholas J. Rengger (2002). International relations in political thought: texts from the ancient Greeks to the 1st World War. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Caesars coins". Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ "Act of Union with England 1707". Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ Summary of in re J Allister

- ^ Protocol legal, court rules, from bbc.co.uk/news

External links

[edit]- Text version of the Articles of Confederation

- Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union

- Articles of Confederation and related resources, Library of Congress

- Today in History: November 15, Library of Congress

- United States Constitution Online—The Articles of Confederation

- Free Download of Articles of Confederation Audio

- Mobile friendly version of the Articles of Confederation