Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geographer

View on Wikipedia

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" and the Greek suffix, "graphy", meaning "description", so a geographer is someone who studies the earth.[1] The word "geography" is a Middle French word that is believed to have been first used in 1540.[2]

Although geographers are historically known as people who make maps, map making is actually the field of study of cartography, a subset of geography. Geographers do not study only the details of the natural environment or human society, but they also study the reciprocal relationship between these two. For example, they study how the natural environment contributes to human society and how human society affects the natural environment.[3]

In particular, physical geographers study the natural environment while human geographers study human society and culture. Some geographers are practitioners of GIS (geographic information system) and are often employed by local, state, and federal government agencies as well as in the private sector by environmental and engineering firms.[4]

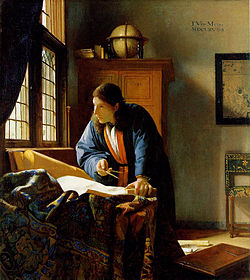

The paintings by Johannes Vermeer titled The Geographer and The Astronomer are both thought to represent the growing influence and rise in prominence of scientific enquiry in Europe at the time of their painting in 1668–69.

Areas of study in geography

[edit]| History of geography |

|---|

|

Subdividing geography is challenging, as the discipline is broad, interdisciplinary, ancient, and has been approached differently by different cultures. Attempts have gone back centuries, and include the "Four traditions of geography" and applied "branches."[5][6][7]

Four traditions of geography

[edit]The four traditions of geography were proposed in 1964 by William D. Pattison in a paper titled "The Four Traditions of Geography" appearing in the Journal of Geography.[5][8] These traditions are:

- spatial or locational tradition[5][8]

- area studies or regional tradition[5][8]

- Human–Environment interaction tradition (originally referred to as the "man-land tradition")[5][8]

- Earth science tradition[5][8]

Branches of geography

[edit]The UNESCO Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems subdivides geography into three major fields of study, which are then further subdivided.[6][7] These are:

- Human geography: including urban geography, cultural geography, economic geography, political geography, historical geography, marketing geography, health geography, and social geography.[9]

- Physical geography: including geomorphology, hydrology, glaciology, biogeography, climatology, meteorology, pedology, oceanography, geodesy, and environmental geography.[10]

- Technical geography: including geoinformatics, geographic information science, geovisualization, and spatial analysis.

Five themes of geography

[edit]The National Geographic Society identifies five broad key themes for geographers:

Notable geographers

[edit]

- Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) – published Cosmos and founder of the sub-field biogeography.

- Arnold Henry Guyot (1807–1884) – noted the structure of glaciers and advanced understanding in glacier motion, especially in fast ice flow.

- Carl O. Sauer (1889–1975) – cultural geographer.

- Carl Ritter (1779–1859) – occupied the first chair of geography at Berlin University.

- David Harvey (born 1935) – Marxist geographer and author of theories on spatial and urban geography, winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Doreen Massey (1944–2016) – scholar in the space and places of globalization and its pluralities; winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Edward Soja (1940–2015) – worked on regional development, planning and governance and coined the terms synekism and postmetropolis; winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Ellen Churchill Semple (1863–1932) – first female president of the American Association of Geographers.

- Jovan Cvijić (1865–1927) – Serbian geographer, geologist, sociologist and human geographer; father of the karst geomorphology

- Eratosthenes (c. 276 – c. 195/194 BC) – calculated the size of the Earth.

- Ernest Burgess (1886–1966) – creator of the concentric zone model.

- Gerardus Mercator (1512–1594) – cartographer who produced the Mercator projection

- John Francon Williams (1854–1911) – author of The Geography of the Oceans.

- Karen Bakker (1971-2023), who contributed significantly to the study of intersections between digital technology and the natural environment

- Karl Butzer (1934–2016) – German-American geographer, cultural ecologist and environmental archaeologist.

- Michael Frank Goodchild (born 1944) – GIS scholar and winner of the RGS founder's medal in 2003.

- Milton Santos (1926–2001) – became known for his pioneering works in several branches of geography, notably urban development in developing countries.

- Muhammad al-Idrisi (Arabic: أبو عبد الله محمد الإدريسي; Latin: Dreses) (1100–1165) – author of Nuzhatul Mushtaq.

- Nigel Thrift (born 1949) – originator of non-representational theory.

- Paul Vidal de La Blache (1845–1918) – founder of the French school of geopolitics, wrote the principles of human geography.

- Ptolemy (c. 100 – c. 170) – compiled Greek and Roman knowledge into the book Geographia.

- Radhanath Sikdar (1813–1870) – calculated the height of Mount Everest.

- Roger Tomlinson (1933 – 2014) – the primary originator of modern geographic information systems.

- Halford Mackinder (1861–1947) – co-founder of the London School of Economics, Geographical Association.

- Strabo (64/63 BC – c. AD 24) – wrote Geographica, one of the first books outlining the study of geography.

- Waldo Tobler (1930–2018) – coined the first law of geography.

- Walter Christaller (1893–1969) – human geographer and inventor of central place theory.

- William Morris Davis (1850–1934) – father of American geography and developer of the cycle of erosion.

- Yi-Fu Tuan (1930–2022) – Chinese-American scholar credited with starting humanistic geography as a discipline.

Institutions and societies

[edit]- American Association of Geographers[12]

- American Geographical Society[13]

- North American Cartographic Information Society

- Anton Melik Geographical Institute (Slovenia)

- Gamma Theta Upsilon (international)

- Institute of Geographical Information Systems (Pakistan)

- International Geographical Union

- Karachi Geographical Society (Pakistan)

- National Geographic Society (US)[14]

- Royal Canadian Geographical Society

- Royal Danish Geographical Society

- Royal Geographical Society (UK)[15]

- Russian Geographical Society

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Arrowsmith, Aaron (1832). "Chapter II: The World". A Grammar of Modern Geography. King's College School. pp. 20–21. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "geography (n.)" (Web article). Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. n.d. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Pedley, Mary Sponberg; Edney, Matthew H., eds. (2020). The History of Cartography, Volume 4: Cartography in the European Enlightenment. University of Chicago Press. pp. 557–558. ISBN 9780226339221. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "Geographers : Occupational Outlook Handbook : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". www.bls.gov. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Pattison, William (1964). "The Four Traditions of Geography". Journal of Geography. 63 (5): 211–216. Bibcode:1964JGeog..63..211P. doi:10.1080/00221346408985265. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ a b Sala, Maria (2009). Geography Volume I. Oxford, United Kingdom: EOLSS UNESCO. ISBN 978-1-84826-960-6.

- ^ a b Sala, Maria (2009). Geography – Vol. I: Geography (PDF). EOLSS UNESCO. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Murphy, Alexander (27 June 2014). "Geography's Crosscutting Themes: Golden Anniversary Reflections on "The Four Traditions of Geography"". Journal of Geography. 113 (5): 181–188. Bibcode:2014JGeog.113..181M. doi:10.1080/00221341.2014.918639. S2CID 143168559.

- ^ Nel, Etienne (23 November 2010). "The dictionary of human geography, 5th edition - Edited by Derek Gregory, Ron Johnston, Geraldine Pratt, Michael J. Watts and Sarah Whatmore". New Zealand Geographer. 66 (3): 234–236. Bibcode:2010NZGeo..66..234N. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7939.2010.01189_4.x. ISSN 0028-8144.

- ^ Marsh, William M. (2013). Physical geography : great systems and global environments. Martin M. Kaufman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76428-5. OCLC 797965742.

- ^ "Geography Education @". Nationalgeographic.com. 24 October 2008. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ Freeman, T. W.; James, Preston E.; Martin, Geoffrey J. (July 1980). "The Association of American Geographers: The First Seventy-Five Years 1904-1979". The Geographical Journal. 146 (2): 298. Bibcode:1980GeogJ.146..298F. doi:10.2307/632894. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 632894.

- ^ "AGS History". 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ "National Geographic Society". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ "Royal Geographical Society - Royal Geographical Society (with IBG)". www.rgs.org. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Steven Seegel. Map Men: Transnational Lives and Deaths of Geographers in the Making of East Central Europe. University of Chicago Press, 2018. ISBN 978-0-226-43849-8.

External links

[edit] Media related to Geographers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Geographers at Wikimedia Commons

Geographer

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Scope

Core Definition and Responsibilities

A geographer is a professional who studies the spatial distribution of physical and human phenomena on Earth's surface, analyzing patterns, processes, and interactions between natural environments and human activities.[1] This discipline encompasses both physical geography, which examines landforms, climate, soils, and vegetation, and human geography, which investigates population dynamics, cultural landscapes, economic systems, and urban development.[7] Geographers employ spatial analysis to understand causal relationships, such as how topographic features influence settlement patterns or how resource distribution drives migration flows.[9] Core responsibilities include gathering geographic data from diverse sources, including field observations, satellite imagery, aerial photographs, censuses, and existing maps.[1] [10] They conduct research through methods like surveys, interviews, and focus groups to collect qualitative and quantitative information on spatial phenomena.[1] Geographers then analyze this data to identify trends, such as the impacts of climate variability on agricultural productivity or the spatial inequities in urban infrastructure access.[9] Additional duties involve creating visual representations of data, including maps and models, often using geographic information systems (GIS) software to reveal relationships between variables like elevation, population density, and disease prevalence.[1] They write reports and present findings to inform policy, such as land-use planning or disaster risk assessment, applying empirical evidence to predict outcomes like flood-prone areas based on hydrological data and historical records.[11] Geographers may also engage in fieldwork to verify remote sensing data, ensuring analyses reflect ground-truth conditions.[10]Distinctions from Related Professions

Geographers analyze the spatial distribution of physical and human phenomena, emphasizing interrelationships between places, environments, and societies, whereas cartographers specialize in the technical design, compilation, and visualization of maps as representational tools.[12] This distinction arises because geographers use maps and spatial data to interpret broader patterns, such as migration flows or resource distributions, rather than prioritizing the aesthetic or symbolic accuracy of map production itself.[13] In contrast to surveyors, who employ precise instruments like theodolites and GPS to measure land boundaries, elevations, and features for legal and engineering purposes, geographers focus on synthesizing large-scale spatial data to uncover trends and causal links, such as urban sprawl or climate impacts on settlement patterns.[14] Surveying remains grounded in fieldwork for tangible delimitations, with outputs feeding into construction or property records, while geographic inquiry integrates quantitative and qualitative methods to model dynamic processes across regions.[15] Urban planners apply geographic principles to practical decision-making, including zoning regulations, infrastructure development, and community consultations, often within governmental frameworks to shape built environments.[16] Geographers, however, prioritize theoretical and empirical examination of underlying spatial dynamics, such as economic disparities across metropolitan areas, without the direct mandate for policy implementation or stakeholder mediation that defines planning.[17] Unlike anthropologists, who investigate human evolution, cultural practices, and social organizations through ethnographic methods, geographers center on the locational contexts of these elements, exploring how terrain, climate, and connectivity influence societal formations.[18] Anthropological work delves into symbolic meanings and kinship systems in specific locales, whereas geographic analysis quantifies spatial variances, such as diffusion of cultural traits via trade routes.[19] GIS specialists concentrate on the operational aspects of geographic information systems, including data layering, querying, and software proficiency for tasks like overlay analysis or database management, treating spatial technology as the core competency.[20] Geographers, by comparison, deploy GIS as one methodological tool among many—alongside fieldwork and statistical modeling—to advance holistic understandings of phenomena like environmental vulnerability or geopolitical shifts, prioritizing interpretive synthesis over technical infrastructure.[1]Historical Evolution

Ancient and Classical Foundations

The foundations of geography as a systematic discipline emerged in ancient civilizations through practical mapping and descriptive accounts, predating formal Greek scholarship. In Mesopotamia, the Babylonian Imago Mundi clay tablet, dating to approximately 600 BCE, represents one of the earliest known world maps, depicting the known world as a flat disk surrounded by water with Babylon at the center, accompanied by cosmological and geographical notations.[21] Egyptian contributions included detailed surveys of the Nile River and surrounding lands for administrative and agricultural purposes, such as the Turin Papyrus Map from around 1150 BCE, which illustrated gold mining regions with topographical features and quarries.[22] These efforts prioritized utilitarian knowledge over theoretical inquiry, laying groundwork for later empirical observations without developing abstract spatial concepts.[23] Greek thinkers in the classical period advanced geography toward scientific description and measurement, integrating it with philosophy, astronomy, and exploration. Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276–194 BCE), often credited as the father of geography for coining the term geographia (earth description), calculated the Earth's circumference with remarkable accuracy by comparing the angle of the sun's rays at noon on the summer solstice between Alexandria and Syene (modern Aswan), a difference of about 7.2 degrees or 1/50th of a circle, yielding an estimate of 252,000 stadia (approximately 39,000–46,000 kilometers depending on stade length). [6] He also produced a world map synthesizing known regions and emphasized geography's role in understanding the Earth as humanity's abode. Preceding him, Anaximander (c. 610–546 BCE) created the first Greek world map, portraying a cylindrical Earth centered in the cosmos, while Herodotus (c. 484–425 BCE) provided empirical travel narratives in his Histories, detailing distances, customs, and physical features across Persia, Egypt, and Scythia based on direct observation and inquiry.[22] These works shifted focus from myth to verifiable data, though limited by available exploration.[24] In the Hellenistic and Roman eras, geography matured into a more comprehensive and mathematical pursuit. Strabo (c. 64 BCE–24 CE), in his 17-volume Geographica, compiled descriptive accounts of Europe, Asia, and Libya, drawing on earlier sources like Eratosthenes and emphasizing political geography alongside physical descriptions, such as river systems and mountain ranges, to support imperial administration. Claudius Ptolemy (c. 90–168 CE), working in Alexandria, advanced cartographic precision in his Geographia, introducing a coordinate grid of latitude and longitude for over 8,000 locations, enabling systematic projection of the spherical Earth onto maps despite distortions from his assumptions of a smaller Earth circumference (180,000 stadia).[25] Roman scholars like Pliny the Elder incorporated geographical knowledge into encyclopedic works such as Natural History (77 CE), cataloging regions, resources, and phenomena, but largely built upon Greek foundations without major innovations.[26] This classical synthesis prioritized empirical synthesis over speculation, influencing cartography for centuries despite errors in scale and orientation derived from incomplete data.[27]Medieval and Early Modern Advances

In the medieval period, geographical knowledge advanced significantly in the Islamic world, where scholars integrated classical Greek texts with empirical observations from trade and travel. Muhammad al-Idrisi (c. 1100–1166), an Arab cartographer, compiled the Tabula Rogeriana in 1154 for the Norman king Roger II of Sicily, producing a silver disc map and accompanying text that described regions from Europe to East Asia with relative accuracy based on traveler reports and astronomical data.[28] Ibn Battuta (1304–1369), a Moroccan explorer, documented his 29-year journey covering approximately 117,000 kilometers across Africa, the Middle East, India, and Southeast Asia in his Rihla, providing detailed empirical accounts of climates, societies, and routes that enriched descriptive geography.[29] These works preserved and expanded Ptolemaic frameworks while incorporating non-European data, contrasting with the relative stagnation in systematic geographical inquiry in Western Europe following the Roman Empire's collapse. By the late medieval era, the rediscovery of Ptolemy's Geographia—translated into Latin by Jacobus Angelus around 1406—began revitalizing European cartography, introducing coordinate-based mapping with latitude and longitude grids.[30] This laid groundwork for Renaissance scholars, though practical advances awaited the printing press's invention circa 1440, which enabled wider dissemination of maps and texts. Early modern geography surged during the Renaissance and Age of Discovery (15th–17th centuries), driven by European maritime expeditions that supplied vast new empirical data. Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama's 1497–1499 voyage established the first direct sea route from Europe to India via the Cape of Good Hope, revealing ocean currents and coastal features that transformed understandings of African and Indian geography.[31] German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller's 1507 world map, Universalis Cosmographia, was the first to depict the New World as a separate continent and apply the name "America" to it, based on Amerigo Vespucci's explorations.[32] Abraham Ortelius's Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570) compiled 53 uniform-scale maps into the first modern atlas, systematically organizing global knowledge from recent voyages and classical sources, influencing standardized cartographic practice.[33] Gerardus Mercator advanced nautical cartography with his 1569 world map using a conformal projection that preserved angles for straight-line rhumb navigation, essential for transoceanic sailing despite distorting high-latitude sizes.[34] These innovations shifted geography toward empirical verification and mathematical precision, prioritizing causal mechanisms like wind patterns and spherical geometry over speculative cosmography.Modern Professionalization (19th-20th Centuries)

The professionalization of geography as a distinct academic and vocational field accelerated in the 19th century, primarily in Europe, where systematic teaching and research began to institutionalize the discipline beyond exploratory mapping and descriptive accounts. Carl Ritter established the first dedicated university chair in geography at the University of Berlin in 1825, emphasizing comparative regional studies and the interconnections between physical environments and human societies, which laid foundational pedagogical structures for training geographers.[35] This appointment, supported by Prussian educational reforms, marked a shift toward geography as a rigorous scholarly pursuit, influencing subsequent appointments in German universities and promoting the training of specialists through lectures, seminars, and textual analysis of terrains. Geographical societies played a pivotal role in advocating for the discipline's recognition in higher education and public policy. The Royal Geographical Society, founded in 1830 as the Geographical Society of London and granted royal charter in 1859, advanced professional standards by funding expeditions, hosting lectures, and lobbying for geography's inclusion in school curricula and university programs, thereby fostering a cadre of trained practitioners focused on empirical observation and cartographic precision.[36] Similarly, the American Geographical Society, established in 1851, supported professional development through library resources, map collections, and publications that disseminated methodological standards, aiding the transition from amateur exploration to expert analysis in North America.[37] These organizations standardized practices such as fieldwork documentation and data verification, countering earlier ad hoc approaches by emphasizing verifiable evidence over anecdotal reporting. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, dedicated university departments proliferated, solidifying professional credentials. In Britain, Halford Mackinder's appointment to the first Oxford chair in 1887 exemplified efforts to integrate geography into liberal arts education, with emphasis on geopolitical synthesis and practical training for civil service roles.[38] In the United States, the Association of American Geographers, formed on December 29, 1904, with initial membership of 48 professionals, promoted graduate-level specialization, annual meetings for methodological exchange, and the publication of peer-reviewed research, establishing norms for academic careers in teaching and applied analysis.[39] The International Geographical Union, convened in 1922 under League of Nations auspices, further internationalized standards by coordinating congresses on quantitative surveying and regional monographs, though national variations persisted due to differing emphases on physical versus human aspects. Professionalization also involved the proliferation of specialized journals that enforced evidentiary rigor. The Royal Geographical Society's Journal, initiated in 1831 and evolving into the Geographical Journal by 1893, required contributors to substantiate claims with field measurements and maps, elevating discourse from narrative travelogues to analytical treatises.[40] By the mid-20th century, these developments had produced formalized career paths, with geographers increasingly employed in government surveying, urban planning, and resource management, underpinned by degrees requiring proficiency in topographic analysis and statistical correlations between landscapes and populations. This era's institutional frameworks, while Eurocentric, prioritized causal explanations rooted in observable data, distinguishing professional geographers from general scholars or explorers.Contemporary Developments (Post-1945)

Following World War II, geography underwent a paradigm shift toward greater scientific rigor, influenced by wartime technological innovations and the availability of computing resources. The quantitative revolution, emerging in the mid-1950s primarily in Anglo-American universities, introduced statistical modeling, probability theory, and computer-based simulations to analyze spatial patterns, diffusion processes, and locational decision-making, supplanting earlier idiographic regional descriptions with nomothetic generalizations. This transformation positioned geography as a spatial science capable of hypothesis testing and prediction, as evidenced by early applications in urban land use models like those developed by Walter Christaller and extended computationally.[41][42] Aerial photography, refined during the war for reconnaissance, became a foundational tool post-1945, enabling precise mapping of landforms and human settlements at scales unattainable by ground surveys alone, while quantitative methods facilitated the statistical identification of underlying patterns in these datasets. In physical geography, these advances supported resource management studies, including soil erosion modeling and hydrological forecasting, with empirical data from field stations and early remote sensing contributing to causal understandings of environmental dynamics rather than mere classification.[42][43] The 1960s marked the advent of digital geospatial technologies, culminating in the development of Geographic Information Systems (GIS). In 1963, geographer Roger Tomlinson initiated the Canada Geographic Information System for the Canadian Department of Forestry and Rural Development, the first operational GIS, which integrated vector data on land parcels, soils, and forestry resources to support inventory and planning across 10 million square kilometers, demonstrating the feasibility of overlay analysis for policy decisions. By the 1970s, GIS commercialization—driven by hardware improvements and software like that from Esri—enabled widespread adoption, allowing geographers to perform spatial queries, buffering, and network analysis on multivariate datasets, fundamentally enhancing empirical fieldwork with computational precision.[44][45] In human geography, post-1945 trends emphasized globalization's spatial impacts, including trade networks and labor migration flows, quantified through gravity models and econometric techniques that revealed causal links between economic policies and locational shifts, such as post-colonial urban primacy in developing regions. Urban geography advanced with simulations of sprawl and segregation, incorporating census data to model accessibility and inequality, though later postmodern critiques in the 1980s often subordinated data-driven analysis to interpretive frameworks influenced by institutional biases in academia toward ideological rather than falsifiable explanations.[46] Physical geography progressed through process-oriented studies in geomorphology and climatology, leveraging satellite imagery from programs like Landsat (launched 1972) to track deforestation rates—e.g., 11.1 million hectares annually in tropical regions by the 1980s—and glacial retreat, providing empirical baselines for causal models of anthropogenic forcing over natural variability. Contemporary integrations of machine learning with GIS since the 2010s have further refined predictive mapping, as in flood risk assessments using convolutional neural networks on elevation and precipitation data, underscoring geography's evolution into an interdisciplinary, data-intensive field.[47][45]Education and Training

Academic Requirements and Degrees

A bachelor's degree in geography or a closely related field serves as the foundational academic requirement for entry-level positions in geography, encompassing roles in government agencies, environmental consulting, and GIS analysis.[48] Typical programs require 30 to 46 credit hours in geography, including core courses in physical geography, human geography, cartography, geographic information systems (GIS), remote sensing, and statistics.[49] [50] Students often complete fieldwork, laboratory components, and quantitative methods training to build empirical skills essential for spatial analysis.[51] Advanced degrees are prevalent among professional geographers, with over 40% holding a master's degree and approximately 17% possessing a doctorate, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data analyzed in 2021.[52] A master's degree, typically requiring 30-36 credit hours beyond the bachelor's, is necessary for many non-governmental roles, such as research analysis or specialized consulting, and emphasizes advanced methodologies like spatial modeling and qualitative research.[53] Admission generally demands a minimum GPA of 3.0, letters of recommendation, a statement of purpose, and often GRE scores, though some programs waive the latter.[54] Doctoral programs in geography, culminating in a PhD, are required for academic positions, high-level research, and policy advisory roles, involving 18-90 additional credits, comprehensive examinations, and a dissertation based on original empirical research.[55] [56] While some programs admit directly from a bachelor's, most expect a master's degree, with completion timelines averaging three to five years post-master's.[57] Subfield focus—such as physical or human geography—influences coursework depth, but all emphasize causal analysis of spatial phenomena through data-driven approaches.[58] Professional certifications, like those from the GIS Certification Institute, may supplement degrees but are not substitutes for formal education.[7]Essential Skills and Professional Development

Geographers require a combination of analytical, technical, and interpersonal skills to effectively analyze spatial data, interpret environmental and human patterns, and communicate findings. Analytical skills are fundamental, enabling professionals to evaluate data from diverse sources such as satellite imagery, census records, and field observations, and to discern patterns and causal relationships therein.[1] Computer proficiency is equally critical, particularly in geographic information systems (GIS) software for mapping and spatial analysis, database management, and data visualization tools like Python or R for processing large datasets.[1] Spatial thinking—understanding relationships between locations, scales, and processes—distinguishes geographers and is highly valued in sectors like urban planning and logistics.[59] Communication skills support the dissemination of complex geographical insights through reports, presentations, and visualizations, ensuring accessibility to policymakers and stakeholders.[10] Fieldwork competencies, including safe data collection in varied terrains and ethical research practices, complement quantitative abilities with practical experience.[60] Critical thinking and problem-solving are essential for addressing real-world challenges, such as climate impacts or resource distribution, often requiring interdisciplinary integration with fields like economics or ecology.[61] Professional development for geographers emphasizes lifelong learning to adapt to technological advances and evolving global issues. Membership in organizations like the Association of American Geographers (AAG), founded in 1904 with over 10,000 members, provides access to annual meetings, webinars on career strategies, and job resources that enhance employability across academia, government, and industry.[62][63] The Royal Geographical Society (RGS) offers the Chartered Geographer designation, requiring demonstration of competencies in applying knowledge, innovation, professionalism, and communication, which bolsters credentials for senior roles.[64] Early-career programs, such as AAG's webinar series launched in 2020, focus on networking, resume building, and navigating job markets, targeting recent graduates within a year of completion.[65] Continuing education through workshops on emerging tools like remote sensing or AI-driven modeling ensures relevance, as geospatial technologies evolve rapidly; for instance, proficiency in GIS has become a baseline expectation in 80% of private-sector geography roles.[59] Interdisciplinary certifications, such as those in environmental management or data science, further professional versatility, reflecting the field's shift toward integrated approaches post-2000.[66] Employers prioritize candidates with demonstrated experience in collaborative projects, underscoring the value of internships and publications for career progression.[67]Methodological Toolkit

Empirical Fieldwork and Data Collection

Empirical fieldwork constitutes a foundational method in geography for acquiring primary data through direct observation, measurement, and interaction with physical and human environments, enabling geographers to test hypotheses, validate remote sensing data, and document spatial variations firsthand.[68] This approach contrasts with secondary data reliance by emphasizing in-situ collection to mitigate abstraction errors and capture dynamic processes, such as erosion rates or settlement patterns, which laboratory simulations cannot fully replicate.[69] Fieldwork typically involves systematic planning, including site selection, risk assessments, and ethical considerations for human subjects or protected ecosystems, with data logged via notebooks, GPS devices, or digital recorders to ensure reproducibility.[70] In physical geography, empirical data collection often employs transect surveys, where linear paths across terrains allow measurement of gradients, soil profiles, or vegetation density; for instance, geomorphologists may use clinometers and tape measures to quantify slope angles and sediment transport in riverine or coastal settings.[71] Hydrologists collect water samples for chemical analysis or deploy stream gauges to record discharge volumes, as seen in studies of watershed dynamics where hourly readings over multi-day periods reveal flood response times.[72] Biotic inventories, such as quadrat sampling in ecosystems, quantify species distribution—e.g., placing 1m² frames randomly to count plant cover percentages—providing empirical baselines for biodiversity assessments amid climate shifts.[73] These techniques prioritize replicable protocols to counter environmental variability, like diurnal temperature fluctuations, which can skew readings if not timed consistently.[69] Human geography fieldwork centers on socio-spatial data gathering through structured interviews, questionnaires, and behavioral mapping, yielding qualitative and quantitative insights into migration flows or urban land-use conflicts.[74] Semi-structured interviews with residents, often sampling 20-50 individuals stratified by demographics, elicit perceptions of place attachment, as in studies of rural depopulation where responses are coded for thematic analysis.[75] Land-use surveys categorize parcels via on-site classification schemes like RICEPOTS (residential, industrial, etc.), plotted along transects to map urban expansion; traffic counts at intersections, tallying vehicles over fixed intervals (e.g., 15 minutes hourly), quantify mobility patterns.[71] Participatory mapping engages communities to annotate features on base maps, enhancing accuracy in informal settlements where official records lag.[74] Challenges in empirical fieldwork include sampling biases from inaccessible terrains or respondent reluctance, necessitating randomized selection and pilot testing; for example, weather-dependent coastal surveys may require contingency protocols to maintain dataset integrity.[69] Ethical guidelines, such as informed consent under frameworks like those from the Royal Geographical Society, mandate anonymity in human data to prevent harm, while physical sampling adheres to permits for minimizing ecological disturbance.[76] Advances in portable instrumentation, like handheld spectrometers for soil spectrometry, augment traditional methods without supplanting the observer's interpretive role in contextualizing raw metrics.[77] Overall, rigorous fieldwork underpins causal inferences in geography by linking observable phenomena to underlying processes, though integration with computational validation remains essential for scalability.[68]Quantitative Techniques and Computational Tools

Quantitative techniques in geography encompass statistical and mathematical methods applied to spatial data for hypothesis testing, pattern identification, and predictive modeling. These include descriptive statistics to summarize distributions of geographic phenomena, such as measures of central tendency and dispersion for variables like population density or elevation, and inferential statistics for estimating parameters from samples, including confidence intervals and hypothesis tests on spatial autocorrelation.[78] Spatial statistics extend these by accounting for location dependencies, using techniques like Moran's I to detect clustering in areal data or geostatistics like kriging for interpolating continuous surfaces from point samples.[79] Regression analysis, both linear and spatial variants such as geographically weighted regression, models relationships between geographic variables, for instance correlating land use with socioeconomic factors while adjusting for spatial heterogeneity.[80] Time-series analysis handles temporal dynamics in spatial contexts, applying autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models to forecast trends like urban expansion rates. Network analysis quantifies connectivity in transport or migration graphs, computing metrics such as shortest paths or centrality indices.[81] Computational tools have revolutionized these techniques by enabling large-scale data processing. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) integrate hardware, software, and data for capturing, managing, and visualizing spatial information, supporting overlay analysis to combine layers like soil types and rainfall for suitability mapping. Open-source options like QGIS and proprietary systems like ArcGIS facilitate vector and raster operations, including buffering and topological queries.[82][83] Remote sensing provides primary data inputs via satellite or aerial imagery, measuring electromagnetic radiation to derive land cover classifications or vegetation indices like NDVI, with resolutions down to meters as in Landsat missions since 1972. Statistical software such as R or Python libraries (e.g., GeoPandas, rasterio) perform advanced analyses, including machine learning for image segmentation. High-performance computing clusters support simulations of geographic processes, like agent-based models of diffusion or climate downscaling.[84][80] Integration of big data sources—GPS trajectories, IoT sensors, and social media geotags—enhances quantitative rigor, enabling real-time spatial analytics via cloud platforms, though challenges persist in data quality and bias correction. These tools, rooted in the quantitative revolution of the mid-20th century, prioritize empirical validation over qualitative inference, fostering causal insights into spatial phenomena.[85]Qualitative and Theoretical Approaches

Qualitative approaches in geography emphasize the collection and analysis of non-numerical data to explore the meanings, experiences, and social constructions associated with places, landscapes, and human-environment interactions. These methods, prevalent in human geography since the late 20th century, include in-depth interviews, participant observation, ethnography, and discourse analysis, which allow researchers to capture subjective perspectives and contextual nuances that quantitative techniques may overlook.[86] [87] For instance, ethnographies in urban geography have documented residents' lived experiences of gentrification, revealing power dynamics and cultural displacements not quantifiable through census data alone.[88] Such inductive strategies prioritize thick description and theory-building from empirical observations, contrasting with deductive hypothesis-testing in positivist paradigms.[89] Theoretical frameworks underpinning qualitative geography often draw from interpretive paradigms, which view knowledge as co-constructed through human interpretation rather than objective measurement. Hermeneutics and phenomenology, for example, focus on understanding the "lifeworld" of spatial practices, examining how individuals perceive and imbue meaning into environments.[90] [91] In human geography, these align with broader philosophies like structuration theory, which analyzes the interplay of agency and structure in shaping geographic phenomena, as applied in studies of migration and identity formation.[92] Critical theoretical approaches, influenced by Marxism and post-structuralism, interrogate power relations in space, such as through analyses of uneven development or colonial legacies, though these have faced scrutiny for prioritizing ideological critique over falsifiable claims.[93] Feminist and postcolonial theories further extend this by emphasizing embodied knowledges and marginalized voices, enabling qualitative inquiries into gender-specific spatial mobilities or indigenous land narratives.[92] While qualitative methods offer depth in revealing causal mechanisms rooted in human cognition and culture—such as how place attachment influences environmental stewardship—they are critiqued for potential subjectivity and limited generalizability, necessitating rigorous reflexivity and triangulation for credibility.[91][88] In practice, geographers increasingly integrate qualitative insights with mixed methods, as seen in qualitative GIS applications that map narrative data onto spatial contexts to enhance interpretive validity.[94] This evolution reflects a pragmatic recognition that theoretical pluralism, grounded in empirical scrutiny, better approximates causal realities in complex socio-spatial systems than singular paradigms.[95]Subfields and Areas of Focus

Physical Geography

Physical geography is the branch of geography that investigates the natural processes shaping the Earth's surface, encompassing spatial patterns of landforms, climate, soils, vegetation, and water systems.[96] It emphasizes empirical analysis of environmental dynamics, integrating observations from the lithosphere (solid Earth features), hydrosphere (water bodies and cycles), atmosphere (weather and climate), and biosphere (living organisms and ecosystems).[97] Unlike human geography, physical geography prioritizes causal mechanisms driven by physical laws, such as tectonic forces, solar radiation, and gravitational influences, rather than anthropogenic factors.[98] Key subdisciplines include geomorphology, which studies the origin and evolution of landforms through processes like erosion, sedimentation, and tectonic uplift—for instance, the formation of river valleys via fluvial action or mountain ranges via plate collisions.[99] Climatology examines atmospheric circulation, temperature gradients, and precipitation regimes, often using data from weather stations and satellite observations to model phenomena like El Niño-Southern Oscillation events that alter global rainfall patterns.[99] Hydrology focuses on the distribution, movement, and quality of water resources, including groundwater recharge rates (typically measured in meters per year) and flood dynamics influenced by basin topography.[99] Biogeography analyzes the geographic distribution of species and ecosystems, linking factors like soil pH levels (ranging from acidic podzols to alkaline chernozems) and altitudinal zonation to biodiversity gradients, as seen in latitudinal decreases in species richness from equator to poles.[99] Pedology, the study of soils, complements these by detailing formation processes (pedogenesis) over timescales of thousands to millions of years, influenced by parent material, climate, and biota.[100] Physical geographers employ interdisciplinary tools such as remote sensing and geographic information systems (GIS) to quantify spatial variations, for example, mapping deforestation rates at 10-15 million hectares annually through Landsat imagery analysis.[101] This subfield contributes to understanding natural hazards, like the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption's ash dispersion modeled via atmospheric simulations, and informs conservation by delineating biomes such as tundra (covering 10% of Earth's land surface with permafrost depths up to 1,000 meters).[102] Empirical data from field measurements, such as river discharge volumes in cubic meters per second, underpin predictions of environmental change, emphasizing verifiable patterns over speculative narratives.[103]Human Geography

Human geography examines the spatial differentiation and organization of human activities, including their patterns of distribution, interaction, and interrelationships with the physical environment.[104] This field analyzes how human behaviors, institutions, and processes shape and are shaped by geographic contexts, emphasizing concepts such as place (localized meanings and attachments), space (relational and absolute dimensions of human interaction), scale (from local to global hierarchies), and region (clustered spatial units defined by shared characteristics).[105] Unlike physical geography, which prioritizes natural systems, human geography centers on anthropogenic factors like migration, resource use, and territoriality, often revealing causal links between environmental constraints and societal adaptations—such as how topography influences settlement density or climate variability drives agricultural specialization.[104] Major subfields delineate specialized inquiries: economic geography investigates locational decisions in production, trade, and markets, evidenced by models like central place theory explaining retail hierarchies in urban systems;[104] cultural geography maps the diffusion of languages, religions, and traditions, tracking phenomena like the global spread of English speakers exceeding 1.5 billion by 2020;[105] political geography dissects state formations, borders, and conflicts, including empirical analyses of electoral geographies where voting patterns correlate with socioeconomic divides;[104] urban geography studies metropolitan growth, with data showing over 55% of the world's population urbanized by 2018 per United Nations estimates;[104] population geography quantifies demographic shifts, such as fertility rates declining to 2.4 births per woman globally in 2021;[104] and social geography probes inequalities, including spatial segregations in housing markets where income disparities predict neighborhood clustering.[105] These areas integrate human-environment dynamics, as in environmental geography's assessment of land-use changes driving deforestation rates of 10 million hectares annually in the 2010s.[104] Post-1945 developments marked paradigm shifts: the quantitative revolution of the 1950s–1960s introduced statistical modeling and computer-assisted analysis, enabling predictive frameworks like gravity models for migration flows (e.g., correlating distance and population size to forecast interstate moves in the U.S., where 28 million people relocated annually by the 1960s).[106] This positivist emphasis on empirical verification faced critique in the 1970s for neglecting power structures, prompting radical geography's adoption of Marxist lenses to highlight capitalist spatial fixes, such as uneven development in global peripheries.[107] Humanistic and behavioral approaches concurrently stressed individual agency and perception, using surveys to map cognitive maps of urban navigation.[105] By the 1980s–1990s, a cultural turn incorporated postmodern deconstructions, expanding to non-human actors like animals in relational spaces, though empirical critiques note these often prioritize interpretive narratives over falsifiable data.[104] Methodologically, human geographers blend quantitative tools—GIS for spatial autocorrelation analysis, revealing clustering in phenomena like disease outbreaks (e.g., COVID-19 hotspots in 2020)—with qualitative techniques, including participant observation and archival research to unpack historical contingencies in place-making. Mixed-methods studies, such as integrating census data with ethnographic interviews, address limitations of singular paradigms, as in examinations of gentrification where econometric regressions quantify rent hikes (up 20–30% in U.S. cities post-2000) alongside resident narratives of displacement.[108] These approaches underpin applications in policy, from zoning reforms informed by urban sprawl metrics to trade analyses projecting GDP impacts of infrastructure corridors like China's Belt and Road Initiative, spanning 140 countries by 2023.[104] Despite ideological variances—radical strands drawing from structuralism have been faulted for underemphasizing individual incentives verifiable in market data—advances in big data and remote sensing continue to refine causal inferences on human spatial behaviors.[107]Environmental and Integrated Geography

Environmental geography focuses on the dynamic interactions between human societies and the natural environment, analyzing how anthropogenic activities alter ecosystems and how environmental conditions shape human behaviors and adaptations. This subfield emphasizes causal mechanisms, such as land-use changes driving biodiversity loss or hydrological modifications affecting water availability, drawing on empirical evidence from field observations and spatial data analysis.[109][110] Unlike purely physical or human geography, it prioritizes synthesis, examining processes like urbanization's role in habitat fragmentation, where urban expansion from 1950 to 2020 converted approximately 1.2 million square kilometers of natural land globally, as documented in satellite-based assessments.[111] Integrated geography represents the confluence of physical and human geographic paradigms, adopting a holistic lens to elucidate spatial dimensions of human-environmental systems without reducing complex phenomena to isolated variables. It addresses feedbacks, such as how deforestation in tropical regions exacerbates regional climate variability through altered albedo and evapotranspiration rates, integrating biophysical models with socioeconomic drivers.[112][113] This approach counters disciplinary silos by incorporating non-reductionist analyses, for instance, evaluating how policy interventions like reforestation programs in China since 1999 have mitigated soil erosion across 25 million hectares while influencing rural livelihoods.[114] Key applications include assessing resource depletion, where geographers quantify dependencies like global freshwater extraction exceeding sustainable yields by 20% in stressed basins as of 2020, informing adaptive strategies grounded in causal realism rather than unsubstantiated projections.[110] Critiques within the field highlight overreliance on modeling that may amplify uncertainties in long-term forecasts, underscoring the need for robust, data-verified linkages over speculative narratives. Integrated efforts also extend to pollution dynamics, tracing heavy metal contamination from industrial sites to downstream ecosystems via fluvial transport, with empirical studies revealing bioaccumulation factors in aquatic species exceeding safe thresholds by orders of magnitude in affected regions.[109][111]Controversies and Critiques

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Paradigms

The quantitative paradigm in geography prioritizes numerical data, statistical analysis, and mathematical modeling to identify patterns, test hypotheses, and predict spatial phenomena, drawing on positivist principles that emphasize objectivity and replicability.[115] This approach gained prominence during the Quantitative Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s, when geographers adopted tools like regression analysis, central place theory, and early computational methods to shift from idiographic regional descriptions to nomothetic, generalizable laws of spatial organization, influenced by post-World War II demands for operational research and military applications.[116] Empirical verification remains a core strength, as quantitative techniques process large datasets—such as GIS layers or census statistics—to yield falsifiable results, enabling causal inferences supported by probability assessments rather than anecdotal evidence.[117] In contrast, the qualitative paradigm employs interpretive methods like ethnography, discourse analysis, and participant observation to explore subjective experiences, cultural meanings, and power dynamics in place-making, often aligned with constructivist or post-structuralist epistemologies that view knowledge as contextually produced.[89] Emerging as a counterpoint in the 1970s amid critiques of positivism's alleged neglect of human agency, qualitative geography flourished in subfields like cultural and political geography, where non-numerical data from interviews or archival narratives reveal nuances unattainable through aggregation.[118] Its flexibility suits exploratory inquiries in complex social environments, such as informal settlements where standardized surveys falter, but it relies on researcher judgment, raising concerns over inter-subjectivity and selective framing.[119] Controversies arise from epistemological incompatibilities: proponents of quantitative methods argue that qualitative findings lack scalability and rigor, as small-sample insights resist statistical validation and may embed unexamined researcher biases, particularly in ideologically driven analyses prevalent in academic human geography departments.[119][89] Qualitative advocates counter that quantitative approaches oversimplify causality by treating variables as isolated, ignoring embedded socio-historical contexts and equating correlation with mechanism, as seen in early spatial models that underperformed in dynamic urban systems.[120] Empirical evidence from mixed-methods studies suggests quantitative dominance in physical and economic geography yields more predictive power for policy applications, such as resource allocation models, while qualitative contributions excel in hypothesis generation but falter in replication; debates persist over integration, with calls for triangulation to mitigate each paradigm's blind spots, though institutional preferences in geography curricula often tilt toward qualitative training amid broader humanities influences.[108][121]Ideological Influences and Biases

Human geography has been profoundly shaped by Marxist theory since the 1970s, with radical geography applying concepts of class struggle, capital accumulation, and spatial uneven development to explain urban and regional disparities. This strand, formalized through works analyzing the production of space under capitalism, positioned geography as a tool for critiquing systemic inequalities rather than purely descriptive analysis.[122] Pioneers like David Harvey extended these ideas, interpreting globalization and neoliberal policies as mechanisms reinforcing geographic exploitation, influencing subsequent research on gentrification and labor geographies.[123] Critical geography, evolving from Marxist roots, incorporates postmodern, feminist, and postcolonial lenses to deconstruct power relations in space, often framing landscapes as sites of contested ideologies. This paradigm shift, prominent in Anglo-American scholarship, emphasizes subjective narratives over quantitative models, leading to studies prioritizing identity politics and environmental justice.[107] However, such approaches have drawn criticism for subordinating empirical rigor to normative agendas, as seen in assessments of structural Marxism's overreliance on abstract economic determinism at the expense of local contingencies.[124] In contrast, physical geography largely adheres to positivist methods, focusing on measurable phenomena like geomorphology and climatology, with minimal ideological overlay. Yet, even here, integrations with human geography—such as in environmental studies—can import biases, evident in research amplifying anthropogenic climate narratives while downplaying natural variability. Broader academic trends exacerbate this: geography faculties, mirroring humanities disciplines, exhibit a left-leaning skew, with surveys of social sciences indicating overrepresentation of progressive viewpoints that correlate with skepticism toward free-market spatial policies.[125] This homogeneity risks echo chambers, where dissenting analyses, such as those questioning state-driven urban planning, face publication hurdles.[126] Geographical parochialism compounds ideological tilts, as human geography curricula and citations disproportionately favor Northern, urban-centric perspectives, marginalizing non-Western or rural empirical insights.[127] Critics contend this reflects causal realism deficits, where ideological priors—rooted in anti-capitalist frameworks—override data-driven causal chains, as in urban planning debates reviving Marxist critiques amid evident policy failures.[128] Truth-seeking requires balancing these influences with diverse sourcing, acknowledging academia's systemic progressive bias that privileges redistributional over efficiency-based geographic interpretations.[129]Applications and Societal Impact

Careers in Government and Policy

Geographers frequently serve in federal government agencies, where approximately 63% of professionals in the field are employed, performing roles such as scientists, researchers, administrators, resource planners, policy analysts, project managers, and technical specialists.[130][11] These positions leverage geographic expertise in spatial analysis, GIS mapping, and data interpretation to inform decision-making on land use, resource management, and infrastructure development.[1] For instance, at the U.S. Department of the Interior, geographers analyze satellite imagery and field data to extract landform features, recommend data visualization methods, and advise on policy and planning related to natural resources.[131] In policy-oriented roles, geographers contribute to environmental regulation, urban planning, and hazard mitigation by providing geospatial insights that underpin evidence-based strategies.[11] The U.S. Geological Survey employs geographers under the GS-0150 series, requiring advanced professional experience equivalent to GS-13 level for senior positions, focusing on geographic research that supports federal resource policies.[132] Similarly, the State Department's Office of the Geographer and Global Issues addresses geographic boundaries, maritime claims, and transnational challenges, integrating spatial data into diplomatic and policy frameworks.[133] At state and local levels, geographers often act as urban and regional planners or pollution managers, applying locational intelligence to zoning, transportation projects, and ecosystem services in conservation efforts.[7][134] Entry into these careers typically requires a bachelor's degree in geography or a related field with at least 24 semester hours in geographic coursework, enabling federal hiring for positions involving fieldwork, census analysis, and advisory support to policymakers.[135][1] Geographers' interdisciplinary skills in quantitative modeling and qualitative assessment enhance policy efficacy, as seen in applications to public infrastructure planning like highways and bridges, where spatial data identifies optimal routes and mitigates environmental impacts.[11] This role extends to international policy, where geographic analysis informs global resource disputes and boundary delineations, underscoring the field's utility in causal, location-specific governance challenges.[133]Roles in Industry and Research

Geographers in the private sector leverage spatial analysis, geospatial technologies, and location intelligence to support corporate decision-making, with roles often embedded in fields like logistics, real estate, and environmental consulting.[59] For instance, they conduct site selection analyses for retail chains, optimizing store locations based on demographic data and accessibility metrics, or develop supply chain models using GIS software to minimize transportation costs.[59] In energy and utilities, geographers map resource distributions and infrastructure vulnerabilities, aiding in pipeline routing or renewable energy site evaluations, where firms like ESRI report demand for such expertise in handling large-scale spatial datasets.[136] Employment data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that geographers in professional, scientific, and technical services—encompassing many private research and consulting roles—earned a median annual wage of $81,970 as of 2019, with projections for steady growth driven by data analytics needs.[7] In research-oriented positions, geographers contribute to empirical investigations of spatial patterns and processes, often in academic institutions or specialized think tanks. Academic roles include professorial positions focused on fieldwork, modeling climate impacts, or analyzing urbanization trends, with the Association of American Geographers noting opportunities from tenure-track faculty to non-tenure adjuncts across K-12 to research universities.[137] Beyond universities, geographers in private research firms or think tanks like the RAND Corporation apply quantitative methods to topics such as geopolitical risk assessment or resource scarcity forecasting, producing reports that inform corporate strategy without the ideological overlays common in some public-sector analyses.[137] These roles emphasize verifiable data from satellite imagery, census records, and econometric models, with outputs including peer-reviewed publications or proprietary datasets; for example, geographers at firms like McKinsey use spatial econometrics to evaluate market expansions, drawing on causal linkages between geography and economic outcomes.[59] Key industry and research roles for geographers include:- GIS and Data Analysts: Processing geospatial data for business intelligence, prevalent in tech firms like Google or consulting giants, where skills in ArcGIS or Python scripting enable predictive modeling of consumer behavior.[59]

- Environmental Consultants: Assessing site-specific risks for development projects, such as flood zoning or habitat fragmentation, with private firms employing geographers to comply with regulations like the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act.[3]

- Research Scientists in Think Tanks: Conducting studies on migration patterns or trade flows, often using longitudinal datasets to test hypotheses on spatial causality, as seen in organizations prioritizing evidence over advocacy.[138]

- Cartographers and Location Strategists: Creating customized maps for logistics optimization, with private-sector demand rising 5-7% annually per BLS projections for related occupations through 2030.[139]