Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

A Sea Symphony

View on Wikipedia

A Sea Symphony is a work of just over an hour's length for soprano, baritone, chorus and large orchestra written by Ralph Vaughan Williams between 1903 and 1909. The first and longest of his nine symphonies, it was first performed at the Leeds Festival in 1910 with the composer conducting. It is one of the first symphonies in which a chorus is used throughout as an integral part of the texture and it helped set the stage for a new era of symphonic and choral music in Britain during the first half of the 20th century.

Background

[edit]When Vaughan Williams was a young man the sea was a popular subject for composers. The biographer Michael Kennedy cites as examples Elgar's Sea Pictures (1899), Debussy's La mer (1905), Stanford's Songs of the Sea (1904), and Frank Bridge's The Sea (1911).[1] Another inspiration for some British composers in the first half of the 20th century was the poetry of Walt Whitman, set by, among others, Stanford and Charles Wood and later Delius, Holst, and Hamilton Harty.[2] Vaughan Williams was introduced to Whitman's work by Bertrand Russell while they were undergraduates at Cambridge.[2] Although some of Vaughan Williams's early literary enthusiasms cooled in his later years he remained a lifelong admirer of Whitman.[3] The musicologist Elliott Schwartz has commented that Vaughan Williams was particularly attracted to Whitman by tendencies that are paralleled in his music: "the concern for the development of a national art independent of foreign influences and the recurring theme of mysticism and exploration".[4] The music critic of The Times wrote, "poet and composer are marvellously akin".[5]

In 1903 Vaughan Williams began to sketch a Whitman choral work tentatively called "Songs of the Sea". The musicologist Alain Frogley comments that the finished work reflects several influences in Vaughan Williams's early development: "a disparate range of styles and influences, the latter including Brahms (Ein deutsches Requiem in particular), Parry, Stanford, Elgar, Wagner, Tchaikovsky and (to a lesser extent) Debussy and Ravel, along with folk-song and hints of Tudor music".[6] The work evolved into A Sea Symphony, but before that was completed Vaughan Williams composed Toward the Unknown Region, setting an 1868 poem from Whitman's Whispers of Heavenly Death. This setting, for chorus and orchestra, was well received at its premiere during the 1907 Leeds Festival.[7]

During the six-year gestation of the symphony it took various forms. For a while Vaughan Williams labelled it "The Ocean Symphony". The scherzo and slow movement were sketched first, followed by parts of the first movement and finale. In 1906 the composer wrote a movement for baritone and women's chorus called "The Steersman", but discarded it.[8] The final four-movement version used lines from three of Whitman's poems in his collection Leaves of Grass: "Sea Drift", "Song of the Exposition" and "Passage to India".[9]

Premiere

[edit]The composer conducted the first performance, which was given at the Leeds Festival in 1910, with the festival's orchestra and chorus and the soloists Cicely Gleeson-White and Campbell McInnes.[5] It was a considerable success. The Times commented, "It will not be surprising if the Festival of 1910 is remembered in the future as 'the Festival of the Sea Symphony' just as that of 1904 is remembered as 'the Everyman Festival' or that of 1886 as 'the Golden Legend year'.”[5]

Structure

[edit]At just over an hour A Sea Symphony is the longest of Vaughan Williams's nine symphonies. Although it represents a departure from the traditional Germanic symphonic tradition of the time, it follows a fairly standard symphonic outline: fast introductory movement, slow movement, scherzo, and finale. Frogley writes that the work's status as a true symphony has been disputed, "and it is certainly a hybrid work in terms of genre, combining elements of symphony, oratorio and cantata". He adds that the work is more fully choral than, for example, Mahler's symphonies with voices: "the choir or soloists are heard virtually throughout; this necessarily dilutes its ability to pursue some more traditionally symphonic processes". The analyst David Cox writes that the work is symphonic: "The shape of the first movement … is governed by the words, but is recognizably in sonata form, with first and second subjects, development and recapitulation. Similarly, the slow movement is in ternary form".[10]

The four movements are:

- A Song for All Seas, All Ships (baritone, soprano, and chorus)

- On the Beach at Night, Alone (baritone and chorus)

- Scherzo: The Waves (chorus)

- The Explorers (baritone, soprano, semi-chorus, and chorus)

The first movement lasts roughly twenty minutes; the inner movements approximately eleven and eight minutes, and the finale lasts roughly thirty minutes.

Text

[edit]Vaughan Williams set sections from the following poems in A Sea Symphony:

* Movement 1: “Song of the Exposition” and “Song for all Seas, all Ships"

Behold, the sea itself,

And on its limitless, heaving breast, the ships;

See, where their white sails, bellying in the wind, speckle the green and blue,

See, the steamers coming and going, steaming in or out of port,

See, dusky and undulating, the long pennants of smoke.

1 To-day a rude brief recitative,

Of ships sailing the seas, each with its special flag or ship-signal,

Of unnamed heroes in the ships—of waves spreading and spreading far as the eye can reach,

Of dashing spray, and the winds piping and blowing,

And out of these a chant for the sailors of all nations,

Fitful, like a surge.

Of sea-captains young or old, and the mates, and of all intrepid sailors,

Of the few, very choice, taciturn, whom fate can never surprise nor death dismay.

Pick'd sparingly without noise by thee old ocean, chosen by thee,

Thou sea that pickest and cullest the race in time, and unitest nations,

Suckled by thee, old husky nurse, embodying thee,

Indomitable, untamed as thee. ...

2 Flaunt out O sea your separate flags of nations!

Flaunt out visible as ever the various ship-signals!

But do you reserve especially for yourself and for the soul of man one flag above all the rest,

A spiritual woven signal for all nations, emblem of man elate above death,

Token of all brave captains and all intrepid sailors and mates,

And all that went down doing their duty,

Reminiscent of them, twined from all intrepid captains young or old,

A pennant universal, subtly waving all time, o'er all brave sailors,

One flag, one flag above all the rest.

Behold, the sea itself,

And on its limitless heaving breast, the ships

All seas, all ships.

* Movement 2: "On the Beach at Night Alone"

On the beach at night alone,

As the old mother sways her to and fro singing her husky song,

As I watch the bright stars shining, I think a thought of the clef of the universes and of the future.

A vast similitude interlocks all, ...

All distances of place however wide,

All distances of time, ...

All souls, all living bodies though they be ever so different, ...

All nations, ...

All identities that have existed or may exist ...,

All lives and deaths, all of the past, present, future,

This vast similitude spans them, and always has spann'd,

And shall forever span them and compactly hold and enclose them.

* Movement 3: "After the Sea-ship", (taken in its entirety):

After the sea-ship, after the whistling winds,

After the white-gray sails taut to their spars and ropes,

Below, a myriad myriad waves hastening, lifting up their necks,

Tending in ceaseless flow toward the track of the ship,

Waves of the ocean bubbling and gurgling, blithely prying,

Waves, undulating waves, liquid, uneven, emulous waves,

Toward that whirling current, laughing and buoyant, with curves,

Where the great vessel sailing and tacking displaced the surface,

Larger and smaller waves in the spread of the ocean yearnfully flowing,

The wake of the sea-ship after she passes, flashing and frolicsome under the sun,

A motley procession with many a fleck of foam and many fragments,

Following the stately and rapid ship, in the wake following.

* Movement 4: "Passage to India"

5 O vast Rondure, swimming in space,

Cover'd all over with visible power and beauty,

Alternate light and day and the teeming spiritual darkness,

Unspeakable high processions of sun and moon and countless stars above,

Below, the manifold grass and waters, animals, mountains, trees,

With inscrutable purpose, some hidden prophetic intention,

Now first it seems my thought begins to span thee.

Down from the gardens of Asia descending ...,

Adam and Eve appear, then their myriad progeny after them,

Wandering, yearning, ..., with restless explorations,

With questionings, baffled, formless, feverish, with never-happy hearts,

With that sad incessant refrain, Wherefore unsatisfied soul? ...

Whither O mocking life?

Ah who shall soothe these feverish children?

Who Justify these restless explorations?

Who speak the secret of impassive earth? ...

Yet soul be sure the first intent remains, and shall be carried out,

Perhaps even now the time has arrived.

After the seas are all crossed, (...)

After the great captains and engineers have accomplished their work,

After the noble inventors, ...

Finally shall come the poet worthy that name,

The true son of God shall come singing his songs.

8 O we can wait no longer,

We too take ship O soul,

Joyous we too launch out on trackless seas,

Fearless for unknown shores on waves of ecstasy to sail,

Amid the wafting winds, (thou pressing me to thee, I thee to me, O soul,)

Caroling free, singing our song of God,

Chanting our chant of pleasant exploration.

O soul thou pleasest me, I thee,

Sailing these seas or on the hills, or waking in the night,

Thoughts, silent thoughts, of Time and Space and Death, like waters flowing,

Bear me indeed as through the regions infinite,

Whose air I breathe, whose ripples hear, lave me all over,

Bathe me O God in thee, mounting to thee,

I and my soul to range in range of thee.

O Thou transcendent,

Nameless, the fibre and the breath,

Light of the light, shedding forth universes, thou centre of them, ...

Swiftly I shrivel at the thought of God,

At Nature and its wonders, Time and Space and Death,

But that I, turning, call to thee O soul, thou actual Me,

And lo, thou gently masterest the orbs,

Thou matest Time, smilest content at Death,

And fillest, swellest full the vastnesses of Space.

Greater than stars or suns,

Bounding O soul thou journeyest forth; ...

9 Away O soul! hoist instantly the anchor!

Cut the hawsers—haul out—shake out every sail! ...

Sail forth—steer for the deep waters only,

Reckless O soul, exploring, I with thee, and thou with me,

For we are bound where mariner has not yet dared to go, ...

O my brave soul!

O farther farther sail!

O daring joy, but safe! are they not all the seas of God?

O farther, farther, farther sail!

Music

[edit]Orchestration

[edit]The symphony is scored for soprano, baritone, chorus and a large orchestra consisting of:

- Woodwinds: two flutes, piccolo, two oboes, cor anglais, two clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon

- Brass: four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba

- Percussion: timpani (F♯2–F3), side drum, bass drum, triangle, suspended cymbal, crash cymbals

- Organ (1st and 4th movements)

- Strings: two harps, and strings.[11]

The chorus sings in all four movements. Both soloists are featured in the first and last movements; only the baritone sings in the second movement. The scherzo is for the chorus and orchestra alone.[9]

Motives

[edit]Musically, A Sea Symphony contains two strong unifying motives. The first is the harmonic motive of two chords (usually one major and one minor) whose roots are a third apart. This is the first thing that occurs in the symphony; the brass fanfare is a B flat minor chord, followed by the choir singing the same chord, singing Behold, the sea. The full orchestra then comes in on the word sea, which has resolved into D major.

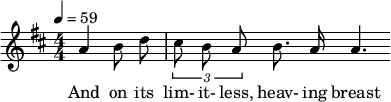

The second motive is a melodic figure juxtaposing duplets and triplets, set at the opening of the symphony (and throughout the first movement) to the words And, on its limitless heaving breast... In the common method of counting musical rhythms, the pattern could be spoken as 'one two-and three-two-three four', showing that the second beat is divided into quavers (for on its) and the third beat is divided into triplets (for limitless).

Reception and legacy

[edit]Hugh Ottaway's 1972 book Vaughan Williams Symphonies presents the following observation in its introduction:

In the Grove article on Vaughan Williams, Ottaway and Alain Frogley call the work:

Recordings

[edit]The first recording of the symphony was made by Decca Records in December 1953 and January 1954 at the Kingsway Hall, conducted by Sir Adrian Boult. It was produced by John Culshaw under the supervision of the composer and was released in March 1954 as LP LXT2907-08.[14] Boult also conducted the first stereophonic recording of the work, made by HMV at the Kingsway Hall in September 1968 and released in December of that year.[15]

| Conductor | Orchestra | Chorus | Soprano | Baritone | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sir Adrian Boult | London Philharmonic Orchestra | London Philharmonic Choir | Isobel Baillie | John Cameron | 1954 |

| Sir Malcolm Sargent | BBC Symphony Orchestra | BBC Choral Society BBC Chorus Christchurch Harmonic Choir |

Elaine Blighton | John Cameron | 1965 |

| Sir Adrian Boult | London Philharmonic | London Philharmonic Choir | Sheila Armstrong | John Carol Case | 1968 |

| André Previn | London Symphony Orchestra | London Symphony Chorus | Heather Harper | John Shirley-Quirk | 1970 |

| Kazuyoshi Akiyama | Osaka Philharmonic | Kobe College Faculty of Music Doshisha Glee Club Osaka Men's Chorus |

Sakae Himoto | Koichi Tajiona | 1973 |

| Gennadi Rozhdestvensky | USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra | Leningrad Musical Society Choir Rimsky-Korsakov Musical School Choir |

Tatiana Smoryakova | Boris Vasiliev | 1988 |

| Vernon Handley | Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra | Liverpool Philharmonic Choir | Joan Rodgers | William Shimell | 1988 |

| Richard Hickox | Philharmonia Orchestra | London Symphony Chorus | Margaret Marshall | Stephen Roberts | 1989 |

| Bernard Haitink | London Philharmonic | London Philharmonic Choir | Felicity Lott | Jonathan Summers | 1989 |

| Bryden Thomson | London Symphony | London Symphony Chorus | Yvonne Kenny | Brian Rayner Cook | 1989 |

| Leonard Slatkin | Philharmonia | Philharmonia Chorus | Benita Valente | Thomas Allen | 1992 |

| Sir Andrew Davis | BBC Symphony | BBC Symphony Chorus | Amanda Roocroft | Thomas Hampson | 1994 |

| Leonard Slatkin | BBC Symphony | BBC Symphony Chorus Philharmonia Chorus |

Joan Rodgers | Simon Keenlyside | 2001 |

| Robert Spano | Atlanta Symphony Orchestra | Atlanta Symphony Chorus | Christine Goerke | Brett Polegato | 2001 |

| Paul Daniel | Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra | Chorus | Joan Rodgers | Christopher Maltman | 2002 |

| Richard Hickox | London Symphony | London Symphony Chorus | Susan Gritton | Gerald Finley | 2006 |

| Howard Arman | MDR Sinfonie-Orchester | MDR Rundfunkchor | Geraldine McGreevy | Tommi Hakala | 2007 |

| Sir Mark Elder | Hallé Orchestra | Hallé Choir | Katherine Broderick | Roderick Williams | 2014 |

| Martyn Brabbins | BBC Symphony | BBC Symphony Chorus | Elizabeth Llewellyn | Marcus Farnsworth | 2017 |

| Andrew Manze | Royal Liverpool Philharmonic | Liverpool Philharmonic Choir | Sarah Fox | Mark Stone | 2017 |

| Dennis Russell Davies | MDR Sinfonie | MDR Rundfunkchor | Eleanor Lyons | Christopher Maltman | 2022 |

- Solurce: Naxos Music Library

References

[edit]- ^ Kennedy, p. 126

- ^ a b Kennedy, p. 82

- ^ Kennedy, p. 100

- ^ Schwartz, p. 20

- ^ a b c "Leeds Musical Festival", The Times, 14 October 1910, p. 10

- ^ Frogley, p. 93

- ^ "Leeds Festival", The Musical Times, 1 November 1907, p. 737

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (2007). Notes to Chandos CD CHSA 5047

- ^ a b Matthew-Walker, Robert (2018). Notes to Hyperion CD 00602458139976

- ^ Cox, p. 115

- ^ Vaughan Williams, p. 1

- ^ Ottaway, p. 5

- ^ Ottaway, Hugh, and Alain Frogley. "Vaughan Williams, Ralph", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001 (subscription required)

- ^ Stuart, Philip. "Decca Complete", Royal Holloway, University of London, 2009

- ^ Simeone, p. 95

Sources

[edit]- Cox, David (1967). "Ralph Vaughan Williams". In Robert Simpson (ed.). The Symphony Volume 2: Elgar to the Present Day. London: Penguin. OCLC 221319144.

- Frogley, Alain (2013). "History and Geography: The Early Orchestral Works and the First Three Symphonies". In Alain Frogley; Aidan J. Thomson (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Vaughan Williams. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13-904324-3.

- Kennedy, Michael (1980). The Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams (second ed.). London and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315453-7.

- Ottaway, Hugh (1972). Vaughan Williams Symphonies. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. ISBN 978-0-56-312242-5.

- Schwartz, Elliott (1964). The Symphonies of Ralph Vaughan Williams. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87-023004-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Simeone, Nigel (1980). "Discography". In Nigel Simeone; Simon Mundy (eds.). Sir Adrian Boult – Companion of Honour. London: Midas Books. ISBN 978-0-85-936212-2.

- Vaughan Williams, Ralph (2024). A Sea Symphony: Full Score. London: Stainer and Bell. ISBN 978-0-85-249973-3.

A Sea Symphony

View on GrokipediaHistory

Composition Process

Ralph Vaughan Williams began sketching ideas for what would become A Sea Symphony in 1903, initially conceiving it as a choral song cycle tentatively titled Songs of the Sea or The Ocean, drawing inspiration from Walt Whitman's poetry.[6] This early work coincided with his deepening engagement with English folk music, as he started collecting traditional songs that year, with later collaboration alongside Percy Grainger in 1905, which influenced the symphony's modal textures and rhythmic vitality.[7] By 1904, Vaughan Williams had made notebook annotations from editions of Whitman's Leaves of Grass, which he had encountered earlier through Cambridge friends like Bertrand Russell, deciding to set exclusively Whitman's sea-themed verses to evoke a symphonic voyage of the human spirit rather than a conventional oratorio.[8] The composition process spanned six years, marked by hesitation and extensive revisions, with Vaughan Williams rejecting substantial material to refine his emerging voice amid influences from Wagner's operatic grandeur—absorbed during his earlier Berlin studies—and Tchaikovsky's symphonic lyricism.[9] By 1906, he had completed the first movement, "A Song for All Seas, All Ships," while experimenting with discarded sections like "The Steersman" for baritone and women's chorus, grappling with the challenge of integrating the chorus as an integral symphonic voice rather than a narrative commentator.[3] Personal experiences, such as a near-drowning incident while bathing on a Yorkshire beach in 1904 during a retreat, intensified his fascination with the sea's mystical power, shaping the work's thematic depth.[8] Further progress accelerated after 1907, when Vaughan Williams studied orchestration with Maurice Ravel in Paris, which helped clarify the large-scale choral-orchestral balance and infused impressionistic subtlety into the score.[7] Without a formal librettist, he personally edited and arranged the Whitman texts, selecting and abridging passages from Sea-Drift and Passage to India to fit the symphonic arc. The full symphony was completed in 1909, following revisions intertwined with his ongoing folk song research, resulting in a "terrifyingly ambitious" structure that unified voice and orchestra in continuous flow.[1][8]Premiere and Early Performances

The world premiere of A Sea Symphony occurred on October 12, 1910, at the Leeds Triennial Musical Festival, conducted by the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams on his 38th birthday.[6] The performance featured the Leeds Festival Chorus of 348 singers and the festival orchestra, with soprano soloist Muriel Foster and baritone Gervase Elwes.[10] The work, lasting approximately 65 minutes, required extensive preparation, including choral rehearsals in London and sectional rehearsals in Leeds and nearby Huddersfield throughout the spring and summer, overseen by festival chorus master Henry Coward.[11] The first London performance took place on February 13, 1913, during a concert of the London Philharmonic Society at Queen's Hall, conducted by Vaughan Williams's former teacher Charles Villiers Stanford.[10] This event marked a significant step in the symphony's dissemination within the United Kingdom, following its northern debut. The symphony's international debut in the United States occurred on April 5, 1922, performed by the New York Philharmonic under Willem Mengelberg.[12] In the years following the premiere, Vaughan Williams made revisions to the score based on performance experiences, including minor scoring adjustments around 1913 and further refinements published in 1918. The full orchestral score was published in 1924, and a new critical edition was released in 2024 by ECS Publishing, incorporating the latest scholarship.[4]Texts

Sources from Whitman

The texts for A Sea Symphony are drawn primarily from Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass, specifically poems published across editions from 1860 to 1881, reflecting the poet's evolving vision of the sea and human experience. The first movement incorporates verses from "Song of the Exposition" (first appearing in the 1871 edition) and "Song for All Seas, All Ships" (from the 1881-1882 "Sea-Drift" cluster), opening with the lines: "Behold, the sea itself, / And on its limitless, heaving breast, the ships; / See, where their white sails, bellying in the wind, speckle the green and blue."[13] The second movement sets "On the Beach at Night Alone" (originally in the 1860 edition, revised in 1881's "Sea-Drift"), beginning: "On the beach at night alone, / As the old mother sways her to and fro singing her husky song." The third movement uses the entirety of "After the Sea-Ship" (1881 "Sea-Drift"), commencing: "After the sea-ship, after the whistling winds, / After the white-gray sails taut to their spars and ropes, / Below, a myriad, myriad waves hastening, lifting up their necks, / Tending in ceaseless flow toward the track of the ship." The fourth movement draws from "Passage to India" (1871 edition, later incorporated into Leaves of Grass), starting with: "O vast Rondure, swimming in space, / Cover'd all over with visible power and beauty, / Alternate light and day and the teeming spiritual darkness, / Unspeakable high processions of sun and moon and countless stars above." Ralph Vaughan Williams accessed Whitman's poetry through English editions that mediated the American original, including the influential 1868 selection by William Michael Rossetti, which introduced British readers to expurgated versions of Leaves of Grass.[3] These UK publications often censored Whitman's explicit references to sexuality and the body to align with Victorian sensibilities, a practice Whitman himself denounced as distorting his work.[3] Vaughan Williams, introduced to Whitman during his Cambridge years around 1892, was part of a broader English "cult of Whitman" that included figures like Edward Carpenter, who promoted unexpurgated translations and selections emphasizing the poet's democratic and mystical ideals.[14][15] Whitman's selected poems embody his transcendentalist philosophy, rooted in the American Romantic tradition, where the sea symbolizes the infinite interconnectedness of humanity, nature, and the cosmos, fostering themes of democracy and spiritual unity. In "Song for All Seas, All Ships," the ocean unites diverse sailors under a shared "ensign" of equality, evoking democratic fellowship across nations. "On the Beach at Night Alone" meditates on cosmic oneness, with the sea and stars as metaphors for the eternal human soul transcending isolation. The waves in "After the Sea-Ship" represent nature's dynamic vitality, mirroring the human spirit's restless pursuit, while "Passage to India" elevates maritime exploration to a spiritual odyssey, linking material voyages to divine enlightenment. These motifs, drawn from Whitman's late-period revisions, underscore his vision of nature as a democratic force elevating the individual to universal harmony.[16]Arrangement and Thematic Role

Vaughan Williams meticulously edited Walt Whitman's poetry by selecting specific lines from five poems in Leaves of Grass—"Song for All Seas, All Ships," "On the Beach at Night Alone," "After the Sea-Ship," "Song of the Exposition," and extracts from "Passage to India"—while excising passages that were overly explicit or personal to suit the symphonic form. He reordered stanzas and occasionally modified words for rhythmic and musical flow, avoiding a continuous narrative in favor of fragmented poetic excerpts that propel the orchestral structure. For instance, in the fourth movement, he combined disparate stanzas from "Passage to India," such as lines invoking the "transcendent" and the soul's voyage, to build toward a climactic spiritual resolution.[17][11][18] The texts trace a narrative arc across the four movements, beginning with collective exploration of the sea's vastness in the first (drawn primarily from "Song for All Seas, All Ships" and "Song of the Exposition"), shifting to solitary contemplation in the second ("On the Beach at Night Alone"), evoking industrious waves in the third ("After the Sea-Ship"), and culminating in transcendent union in the fourth ("Passage to India"). This progression mirrors a soul's journey from physical to metaphysical realms, with the sea serving as a unifying motif symbolizing boundless freedom, eternal mystery, and human aspiration that interconnects the otherwise disparate poems. Oceanic imagery, such as the "limitless, heaving breast" of the waters, underscores themes of infinity and spiritual depth, linking the work's exploratory optimism to ultimate transcendence.[3][17] Rather than a traditional libretto, the texts function as evocative fragments integrated into the symphony's architecture, with assignments to voices enhancing their thematic roles: the soprano delivers lyric, introspective lines (e.g., in the first and fourth movements), the baritone narrates personal reflections (second and fourth), and the chorus provides a collective, elemental voice (dominant in the first and third, with semi-chorus for intimate contrasts in the second and fourth). This vocal layering creates a symphonic dialogue, where the chorus often embodies the sea's communal power while soloists articulate individual wonder, ensuring the poetry drives the work's emotional and structural momentum without rigid storytelling.[17][3][11]Structure

Overall Form

A Sea Symphony is classified as Vaughan Williams's Symphony No. 1, structured in four movements that unfold continuously yet are clearly divided, with a total duration of approximately 60 to 70 minutes.[3][20] The work's innovative form integrates a large chorus throughout all movements, distinguishing it from traditional symphonies where voices are typically reserved for a finale, and features soloists who emerge organically from the choral texture rather than dominating as in operatic or oratorio styles.[3][17] Its tonal plan begins in D major, progressing through modal ambiguities, with the second movement in E minor, the third in G minor, culminating in a resolute E♭ major in the finale, evoking a symbolic journey from turbulent seas to transcendent calm.[2] Blending elements of symphony, oratorio, and cantata, the form alternates symphonic development sections with choral episodes, eschewing recitatives in favor of seamless vocal-instrumental interplay that prioritizes instrumental symphonism over narrative vocal drama, thereby differing from contemporaries like Elgar's oratorios, which emphasize choral storytelling.[3][21] The selected Whitman texts contribute a loose narrative arc of oceanic exploration and spiritual awakening, mirroring this structural voyage.[3]The Four Movements

The first movement, titled "A Song for All Seas, All Ships," is marked Moderato maestoso and lasts 15-20 minutes. It is in D major and opens with a dramatic introduction followed by a bold choral proclamation evoking the vastness of the ocean and humanity's connection to it.[17][22][2] The second movement, "On the Beach at Night Alone," proceeds at Largo sostenuto for about 10-12 minutes in E minor. It features a contemplative baritone solo accompanied by the chorus, painting nocturnal imagery of the sea as a symbol of cosmic unity and introspection.[17][22][2] The third movement, "Scherzo: The Waves," is marked Allegro brillante, spanning 12-15 minutes in G minor. The chorus drives a vivid depiction of the sea's waves and elemental energy, drawing on Whitman's imagery of the ocean's movement.[2] The fourth movement, "The Explorers," is marked Grave e molto adagio leading to Allegro animato, lasting 20-25 minutes in E♭ major. It builds to an ecstatic climax with soprano and chorus, exploring spiritual transcendence and the soul's journey toward enlightenment.[2][17] Brief orchestral transitions connect the movements, providing seamless continuity and underscoring the symphony's overarching nautical narrative.[23]Music

Orchestration

A Sea Symphony is scored for soprano and baritone soloists along with a large SATB chorus.[24][25] The orchestral forces are expansive, reflecting the symphony's choral-orchestral demands and evoking the vastness of the sea through layered textures. The full instrumentation includes:| Section | Instruments |

|---|---|

| Woodwinds | 3 flutes (III doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, E♭ clarinet, 2 B♭ clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon |

| Brass | 4 horns in F, 3 trumpets in B♭, 3 trombones, tuba |

| Percussion | Timpani, snare drum, bass drum, triangle, cymbals (requiring 3-4 players) |

| Harp and Keyboard | 2 harps, organ (ad libitum in some movements) |

| Strings | Violin I, Violin II, viola, cello, double bass |

Motives and Thematic Development

The A Sea Symphony employs a set of recurring motives that unify its structure through cyclic development, drawing on the sea's imagery to symbolize the soul's journey. Central to this is the sea-wave motive, an undulating figure introduced in the opening strings with oscillating major-minor thirds that evoke the ocean's heaving motion, recurring variably across all movements to represent immensity and flux.[26] This motive transforms in tempo and texture, slowing to a meditative pace in the second movement's nocturnal reflection while accelerating in the finale's triumphant voyage.[26] Complementing the sea-wave is the fanfare motive, a bold brass theme that bursts forth in the first movement amid the chorus's proclamation, characterized by vigorous, heraldic gestures in B-flat minor before shifting to D major.[22] In the third movement, this motive undergoes fugal development, adapted into a modified form that propels the scherzo's depiction of turbulent waves, heightening the symphony's dramatic energy.[22] The lyrical motive emerges prominently in the vocal lines, particularly the baritone's descending phrases in the second movement, which convey introspective depth through expansive, tender melodies echoing Whitman's themes of self and cosmos.[26] This motive reappears in transformed echoes during the soprano's climactic passages in the fourth movement, linking personal contemplation to collective transcendence.[26] Vaughan Williams's development techniques emphasize cyclic form, where these motives recur and evolve through repetition and variation, blending symphonic and cantata elements for cohesive progression.[26] Rhythmic elements reinforce this, notably the hemiola created by juxtaposing duplets against triplets in the opening choral entry—"And on its limitless, heaving breast"—to pulse like the ocean's irregular waves, a pattern that persists in later transformations.[27]Influences

Literary Inspirations

Ralph Vaughan Williams' A Sea Symphony draws profoundly from Walt Whitman's transcendentalist philosophy, which emphasizes the unity of the self, nature, and the cosmos, as articulated in Whitman's Leaves of Grass. This worldview posits a harmonious interconnectedness where the individual soul merges with the universal, a concept mirrored in the symphony's structural progression from the tangible, physical depiction of the sea in the opening movements to the spiritual "passage" toward transcendence in the finale.[14] Whitman's poetry provided Vaughan Williams with a democratic and evolutionary alternative to Victorian Christianity, infusing the work with a sense of mystical evolution that elevates human experience beyond the material.[14] In Whitman's oeuvre, the sea symbolizes democratic boundlessness and inclusivity, serving as a vast, egalitarian space where diverse human endeavors converge in optimistic unity. Oceans represent not only physical expanses but also cosmic renewal and freedom, with ships embodying collective aspiration and the endless possibilities of human connection, as seen in poems like those from Sea-Drift and Passage to India.[28] This symbolism influences the symphony's buoyant tone, portraying the sea as a site of national identity and global connectivity rather than isolation or peril.[25] Vaughan Williams' affinity for Whitman stemmed from shared interests in mysticism and pantheism, shaped by his exposure to Ralph Waldo Emerson's transcendentalist essays and Edward Carpenter's introductions to Whitman's work, which highlighted themes of spiritual camaraderie.[14] Carpenter's interpretations, emphasizing Whitman's "manly love" and homosocial bonds, resonated with Vaughan Williams amid England's post-Victorian cultural shift toward embracing American literature's uncensored explorations of comradeship and individualism.[14] By the early twentieth century, Whitman's popularity in Britain had fostered a broader acceptance of these themes, aligning with emerging nationalist and modernist sensibilities.[14] Recent 21st-century scholarship has illuminated underdeveloped links between Whitman and Vaughan Williams through eco-critical lenses, analyzing how the symphony's seascape engages with environmental interdependence and humanity's place within natural cycles. For instance, studies highlight the sea's portrayal as a dynamic force of both domination (via ships and technology) and eternal renewal, reflecting Whitman's eco-poetic vision of interconnected landscapes.[25] Works like Daniel M. Grimley's The Sound of Place (2018) further explore these themes, connecting the symphony's textual and musical elements to contemporary concerns about locality, identity, and ecological harmony.[25]Musical and Stylistic Sources

Vaughan Williams' exposure to Richard Wagner's music profoundly shaped the structural and expressive elements of A Sea Symphony. His visit to the Bayreuth Festival in 1901, where he encountered Wagner's operas including Tristan und Isolde, introduced him to the leitmotif technique and advanced orchestral color, which informed the symphony's thematic development and harmonic palette.[9] The chromaticism characteristic of Tristan und Isolde—with its tension-building half-step progressions and unresolved dissonances—resonates in the second movement's lyrical passages, where Vaughan Williams employs similar descending chromatic lines to evoke emotional depth and the sea's vastness.[29] French impressionism also contributed to the symphony's evocative seascapes, particularly through Vaughan Williams' studies with Maurice Ravel in Paris in 1908. This period acquainted him with Claude Debussy's La mer (1905), whose fluid orchestration and whole-tone scales for depicting wave motion parallel the symphony's third movement scherzo, "The Waves," with its shimmering textures and impressionistic color.[30] Ravel's guidance emphasized modal ambiguity and instrumental blending, elements that Vaughan Williams integrated to heighten the work's atmospheric quality without direct quotation.[30] Within English traditions, teachers Hubert Parry and Charles Villiers Stanford exerted significant influence on the choral aspects of A Sea Symphony. Parry's cantatas, with their grand, homophonic choruses and ethical depth, inspired the symphony's majestic choral writing, evident in the third movement's "Parryesque" stately tunes and expansive textures. Stanford, who scrutinized early drafts and recommended the work for the 1910 Leeds Festival premiere, contributed to its structural cohesion through his emphasis on Germanic choral rigor, as seen in the integrated vocal-orchestral dialogue. Complementing these, Vaughan Williams' folk song collecting from 1904 to 1906 introduced modal inflections—such as Dorian and Mixolydian scales with flattened sevenths—that infuse the symphony's melodies, creating a "modalised tonality" that blends folk simplicity with symphonic scale, particularly in thematic motifs derived from collected tunes.[29] Johannes Brahms' symphonies provided a model for structural rigor, influencing the development sections' motivic working and contrapuntal density in A Sea Symphony. Brahms' technique of expanding short motifs through variation and sequence, as in his Fourth Symphony, parallels Vaughan Williams' approach to evolving sea-themed ideas across movements, ensuring formal balance amid the work's programmatic freedom.[29] Recent scholarship since 2010 has further illuminated these syntheses, highlighting parallel choral experiments with Gustav Holst—such as shared explorations of Whitman texts and modal harmonies in works like Holst's The Mystic Trumpeter—as precursors to Vaughan Williams' innovative vocal-orchestral fusion, with modal repetitions evoking an early repetitive aesthetic akin to proto-minimalism.[31]Reception and Legacy

Initial Response

The premiere of Ralph Vaughan Williams's A Sea Symphony on October 12, 1910, at the Leeds Festival elicited enthusiastic critical acclaim, marking a significant moment in the composer's emerging reputation. In The Times, critic John Alexander Fuller-Maitland praised the work for its "great vitality," describing it as possessing "incessant vigour, immensely broad lights, nobility of conception and imagination," and highlighting the seamless integration of Walt Whitman's poetry with the music's expansive symphonic form.[26] This review positioned the symphony as a landmark achievement, predicting that the festival would be remembered as "the Festival of the Sea Symphony." Similarly, the Daily Telegraph's Robin Legge deemed it "first in importance" among contemporary British compositions, emphasizing its vitality and noble character.[26] The Musical Times review by William Gray McNaught acknowledged the symphony's status as a "serious work of art" and commended its innovative choral deployment, where the chorus functions not merely as accompaniment but as an integral symphonic voice, blending with the orchestra to evoke the sea's vastness and human aspiration.[26] However, McNaught tempered his praise with reservations about the orchestration, noting occasional over-scoring that could obscure textual clarity.[26] Despite such critiques, the premiere drew a full house at Leeds Town Hall, reflecting strong public enthusiasm for this bold choral-orchestral venture amid the festival's celebratory atmosphere.[32] Criticisms emerged from voices favoring more structured symphonic traditions, with some arguing that the work's expansiveness risked diluting thematic focus.[33] The first London performance on February 4, 1913, at Queen's Hall, was conducted by Hugh Allen.[34][35] Early scholarly commentary framed A Sea Symphony within the broader English musical Renaissance, underscoring the symphony's role in fostering a distinctly British symphonic voice, though documentation remains sparse on certain perspectives. Notably, there is limited coverage of female critics' views, such as those from contemporaries like Rosa Newmarch, who might have emphasized the work's poetic and emotional resonance, nor is there substantial exploration of class-based audience reactions, including how working-class attendees at festivals like Leeds engaged with its themes of exploration and unity.[26]Enduring Significance

A Sea Symphony has maintained a prominent place in the performance repertoire since its premiere, with key revivals underscoring its vitality. Sir Adrian Boult's 1954 mono recording with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir marked a significant postwar resurgence, capturing the work's expansive choral-orchestral scope in a landmark Decca release.[5] Boult revisited it in stereo in 1968, further cementing its status through enhanced sonic clarity. In the 2000s, Richard Hickox's recordings with the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, including a 2005 Chandos edition, facilitated international tours by British ensembles, introducing the symphony to global audiences in venues from the United States to Asia.[36] Recent performances reflect ongoing enthusiasm, such as the Colorado Symphony's 2024 rendition under Peter Oundjian with the Colorado Symphony Chorus, emphasizing its choral demands.[37] In 2025, the Seattle Symphony presented it under Gemma New in October, while the London Symphony Orchestra offered a compelling interpretation led by Sir Antonio Pappano in February, and the London Philharmonic Orchestra performed it with Sir Mark Elder on October 31, with the performance broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on November 12.[38][39][40][41] As Vaughan Williams's inaugural symphony, completed in 1909 and premiered in 1910, A Sea Symphony served as a foundational catalyst for his subsequent symphonic output, blending Whitman's oceanic poetry with innovative choral integration to establish his mature voice.[3] It epitomized the English pastoral school, of which Vaughan Williams was the central figure, promoting a modal, folk-infused style that evoked national landscapes and seascapes.[26] The work's influence extended to later British composers, including Michael Tippett, who drew on Vaughan Williams's folksong-based pastoralism in early pieces like his Concerto for Double String Orchestra (1938–1939).[42] Benjamin Britten, while more cosmopolitan, acknowledged the symphony's merits despite stylistic differences, contributing to its role in shaping mid-20th-century English choral traditions.[10] Scholarly attention in the 2010s has deepened understandings of the symphony's textual dimensions, with Alain Frogley exploring its integration of Whitman's verse in broader contextual analyses within The Cambridge Companion to Vaughan Williams (2013), highlighting interpretive layers in the poetry's democratic and exploratory themes.[33] Michael Kennedy, in his comprehensive The Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams (1980, revised 1996), examined the gender dynamics implicit in Whitman's texts, such as the androgynous soul in "On the Beach at Night Alone," as reflected in the work's vocal writing.[10] In the 2020s, amid heightened climate discourse, scholars have revisited the symphony's eco-themes, interpreting its Whitman-inspired evocations of vast seas and exploration as resonant with contemporary environmental concerns, though direct linkages remain interpretive rather than prescriptive.[43] The symphony's cultural role endures through adaptations in choral repertoires and occasional media uses, remaining a staple for professional and amateur ensembles worldwide due to its accessible yet demanding choral-orchestral format.[21] Vaughan Williams's film scores, including sea-themed sequences in works like The 49th Parallel (1941), echo the symphony's watery imagery, though direct excerpts from A Sea Symphony appear sparingly in documentaries focused on British music or nature.[44] Recordings have evolved from Boult's pioneering mono version to high-fidelity digital editions, such as the 2022 Chandos release under Martyn Brabbins with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, which leverages modern engineering for immersive spatial audio.[45] A 2024 RCA Red Seal box set compiling Vaughan Williams's symphonies further illustrates this progression, making the work accessible via streaming platforms.[46]References

- https://www.ideals.[illinois](/page/Illinois).edu/items/45421