Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shoebill

View on Wikipedia

| Shoebill | |

|---|---|

| |

| At the Pairi Daiza in Brugelette, Belgium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Balaenicipitidae |

| Genus: | Balaeniceps Gould, 1850 |

| Species: | B. rex

|

| Binomial name | |

| Balaeniceps rex Gould, 1850

| |

| |

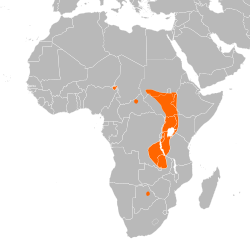

| range | |

The shoebill (Balaeniceps rex), also known as the whale-headed stork, whalebill, and shoe-billed stork, is a large long-legged wading bird. Its name comes from its enormous shoe-shaped bill. It has a somewhat stork-like overall form and was previously classified as a stork in the order Ciconiiformes; but genetic evidence places it with pelicans and herons in the Pelecaniformes. The adult is mainly grey while the juveniles are more brown. It lives in tropical East Africa in large swamps from South Sudan to Zambia.

Taxonomy

[edit]

The shoebill may have been known to Ancient Egyptians[3] but was not classified by Europeans until the 19th century, after skins and eventually live specimens were brought to Europe. John Gould very briefly described it in 1850 from the skin of a specimen collected on the upper White Nile by the English traveller Mansfield Parkyns. Gould provided a more detailed description in the following year. He placed the species in its own genus Balaeniceps and coined the binomial name Balaeniceps rex,[4][5][6] from Latin balaena 'whale' and caput/ceps 'head'.[7] Other common names are whalebill,[8] shoe-billed stork, and whale-headed stork.[9]

Traditionally considered as allied with the storks (Ciconiiformes), it was retained there in the Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy which grouped many unrelated taxa into the Ciconiiformes. Based on osteological evidence, the suggestion of a pelecaniform affinity was made in 1957 by Patricia Cottam.[10] Microscopic analysis of eggshell structure by Konstantin Mikhailov in 1995 found that the eggshells of shoebills closely resembled those of other Pelecaniformes in having a covering of thick microglobular material over the crystalline shells.[11] In 2003, the shoebill was again suggested as closer to the pelicans (based on anatomical comparisons)[12] or the herons (based on biochemical evidence).[13] A 2008 DNA study reinforces their membership among the Pelecaniformes.[14]

So far, two fossilized relatives of the Shoebill have been described: Goliathia from the Early Oligocene of Egypt and Paludiavis from the Late Miocene of Pakistan and Tunisia.[15][16][17] It has been suggested that the enigmatic African fossil bird Eremopezus have features resembling those of the shoebill and the secretary bird.[18]

Description

[edit]

The shoebill is a tall bird, with a typical height range of 110 to 140 cm (43 to 55 in) and some specimens reaching as much as 152 cm (60 in). Length from tail to beak can range from 100 to 140 cm (39 to 55 in) and wingspan is 230 to 260 cm (7 ft 7 in to 8 ft 6 in). Weight has reportedly ranged from 4 to 7 kg (8.8 to 15.4 lb). A male will weigh on average around 5.6 kg (12 lb) and is larger than a typical female of 4.9 kg (11 lb).[19] The signature feature of the species is its huge, bulbous bill, which is pinkish in color with erratic greyish markings. The exposed culmen (or the measurement along the top of the upper mandible) is 18.8 to 24 cm (7.4 to 9.4 in), the third longest bill among extant birds after pelicans and large storks, and can outrival the pelicans in bill circumference, especially if the bill is considered as the hard, bony keratin portion.[19] As in the pelicans, the upper mandible is strongly keeled, ending in a sharp nail. The dark coloured legs are fairly long, with a tarsus length of 21.7 to 25.5 cm (8.5 to 10.0 in). The shoebill's feet are exceptionally large, with the middle toe reaching 16.8 to 18.5 cm (6.6 to 7.3 in) in length, likely assisting the species in its ability to stand on aquatic vegetation while hunting. The neck is relatively shorter and thicker than other long-legged wading birds such as herons and cranes. The wings are broad, with a wing chord length of 58.8 to 78 cm (23.1 to 30.7 in), and well-adapted to soaring.[19]

The plumage of adult birds is blue-grey with darker slaty-grey flight feathers. The breast presents some elongated feathers, which have dark shafts. The juvenile has a similar plumage colour, but is a darker grey with a brown tinge.[9] When they are first born, shoebills have a more modestly-sized bill, which is initially silvery-grey. The bill becomes more noticeably large when the chicks are 23 days old and becomes well developed by 43 days.[19]

Voice

[edit]The shoebill is normally silent, but they perform bill-clattering displays at the nest.[9] When engaging in these displays, adult birds have also been noted to utter a cow-like moo as well as high-pitched whines. Both nestlings and adults engage in bill-clattering during the nesting season as a means of communication. When young are begging for food, they call out with a sound uncannily like human hiccups. In one case, a flying adult bird was heard uttering hoarse croaks, apparently as a sign of aggression at a nearby marabou stork (Leptoptilos crumeniferus).[19]

Flight pattern

[edit]Its wings are held flat while soaring and, as in the pelicans and the storks of the genus Leptoptilos, the shoebill flies with its neck retracted. Its flapping rate, at an estimated 150 flaps per minute, is one of the slowest of any bird, with the exception of the larger stork species. The pattern is alternating flapping and gliding cycles of approximately seven seconds each, putting its gliding distance somewhere between the larger storks and the Andean condor (Vultur gryphus). When flushed, shoebills usually try to fly no more than 100 to 500 m (330 to 1,640 ft).[19] Long flights of the shoebill are rare, and only a few flights beyond its minimum foraging distance of 20 m (66 ft) have been recorded.

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The shoebill is distributed in freshwater swamps of central tropical Africa, from southern Sudan and South Sudan through parts of eastern Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, western Tanzania and northern Zambia. The species is most numerous in the West Nile sub-region and South Sudan (especially the Sudd, a main stronghold for the species); it is also significant in wetlands of Uganda and western Tanzania. More isolated records have been reported of shoebills in Kenya, the Central African Republic, northern Cameroon, south-western Ethiopia, and Malawi. Vagrant strays to the Okavango Basin, Botswana and the upper Congo River have also been sighted. The distribution of this species seems to largely coincide with that of papyrus and lungfish. They are often found in areas of flood plain interspersed with undisturbed papyrus and reedbeds. When shoebill storks are in an area with deep water, a bed of floating vegetation is a requirement. They are also found where there is poorly oxygenated water. This causes the fish living in the water to surface for air more often, increasing the likelihood a shoebill stork will successfully capture it.[20] The shoebill is non-migratory with limited seasonal movements due to habitat changes, food availability and disturbance by humans.[19]

Petroglyphs from Oued Djerat, eastern Algeria, show that the shoebill occurred during the Early Holocene much more to the north, in the wetlands that covered the present-day Sahara Desert at that time.[21]

The shoebill occurs in extensive, dense freshwater marshes. Almost all wetlands that attract the species have undisturbed Cyperus papyrus and reed beds of Phragmites and Typha. Although their distribution largely seems to correspond with the distribution of papyrus in central Africa, the species seems to avoid pure papyrus swamps and is often attracted to areas with mixed vegetation. More rarely, the species has been seen foraging in rice fields and flooded plantations.[19]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]The shoebill is noted for its slow movements and tendency to stay still for long periods, resulting in descriptions of the species as "statue-like". They are quite sensitive to human disturbance and may abandon their nests if flushed by humans. However, while foraging, if dense vegetation stands between it and humans, this wader can be fairly tame. The shoebill is often attracted to poorly oxygenated waters such as swamps, marshes, and bogs where fish frequently surface to breathe. They also seem to exhibit migratory behaviors based upon differences in the surface water level. Immature shoebills abandon nesting sites which increased in the surface water level whereas adult shoebills abandon nesting sites which decreased in surface water level. It is suggested that both adult and immature shoebills prefer nesting sites with similar surface water levels.[22] Exceptionally for a bird this large, the shoebill often stands and perches on floating vegetation, making them appear somewhat like a giant jacana, although the similarly sized and occasionally sympatric Goliath heron (Ardea goliath) is also known to stand on aquatic vegetation. Shoebills, being solitary, forage at 20 m (66 ft) or more from one another even where relatively densely populated. This species stalks its prey patiently, in a slow and lurking fashion. While hunting, the shoebill strides very slowly and is frequently motionless. Unlike some other large waders, this species hunts entirely using vision and is not known to engage in tactile hunting. When prey is spotted, it launches a quick violent strike. However, depending on the size of the prey, handling time after the strike can exceed 10 minutes. Around 60% of strikes yield prey. Frequently water and vegetation is snatched up during the strike and is spilled out from the edges of the mandibles. The activity of hippopotamus may inadvertently benefit the shoebill, as submerged hippos occasionally force fish to the surface.[19]

Breeding

[edit]

The solitary nature of shoebills extends to their breeding habits. Nests typically occur at less than three nests per square kilometre, unlike herons, cormorants, pelicans, and storks, which predominantly nest in colonies. The breeding pair of shoebills vigorously defends a territory of 2 to 4 km2 (0.77 to 1.54 sq mi) from conspecifics. In the extreme north and south of the species' range, nesting starts right after the rains end. In more central regions of the range, it may nest near the end of the wet season in order for the eggs to hatch around the beginning of the following wet season. Both parents engage in building the nest on a floating platform after clearing out an area of approximately 3 m (9.8 ft) across. The large, flattish nesting platform is often partially submerged in water and can be as much as 3 m (9.8 ft) deep. The nest itself is about 1 to 1.7 m (3.3 to 5.6 ft) wide. Both the nest and platform are made of aquatic vegetation. From one to three white eggs are laid. These eggs measure 80 to 90 mm (3.1 to 3.5 in) high by 56 to 61 mm (2.2 to 2.4 in) and weigh around 164 g (5.8 oz). Incubation lasts for approximately 30 days. Both parents actively brood, shade, guard and feed the nestling, though the females are perhaps slightly more attentive. Shoebills use their mandibles to cool their eggs with water during days with high temperatures around 30–33 °C (86–91 °F). They fill their mandible once, swallow the water, and fill another mandible full of water before proceeding back to their nest where they pour out the water and regurgitate the previously swallowed water onto both the nest and eggs.[23] Food items are regurgitated whole from the gullet straight into the bill of the young. Shoebills rarely raise more than one chick but will hatch more. The younger chicks usually die and function as "back-ups" in case the eldest chick dies or is weak. Fledging is reached at around 105 days and the young birds can fly well by 112 days. However, they are still fed for possibly a month or more after this. It will take the young shoebills three years before they become fully sexually mature.[19]

Shoebills are elusive when nesting, so cameras must be placed to observe them from afar to collect behavioral data. There is an advantage for birds that are early breeders, as the chicks are tended for a longer period.[24]

Diet

[edit]Shoebills are largely piscivorous but are assured predators of a considerable range of wetland vertebrates. Preferred prey species have reportedly included marbled lungfish (Protopterus aethiopicus), African lungfish (Protopterus annectens), and Senegal bichir (Polypterus senegalus), various Tilapia species and catfish, the latter mainly in the genus Clarias. Other prey eaten by this species has included frogs, water snakes, Nile monitors (Varanus niloticus) and baby crocodiles. More rarely, small turtles, snails, rodents, small waterfowl and carrion have reportedly been eaten.[25][26][27][28]

Given its sharp-edged beak, huge bill, and wide gape, the shoebill can hunt large prey, often targeting prey bigger than is taken by other large wading birds. In the Bangweulu Swamps of Zambia, fish eaten by this species are commonly in the range of 15 to 50 cm (5.9 to 19.7 in).[29] The main prey items fed to young by the parents were the catfish Clarias gariepinus, (syn. C. mossambicus) and 50 to 60 cm (20 to 24 in) long water snakes.[27] In Uganda, lungfish and catfish were mainly fed to the young.[19] Larger lungfish and catfish were taken in Malagarasi wetlands in western Tanzania. During this study, fish around 60 to 80 cm (24 to 31 in) were quite frequently taken and the largest fish caught by the shoebill was 99 cm long. Fish exceeding 60 cm were usually cut into sections and swallowed at intervals. The entire process from scooping to swallowing ranged from 2 to 30 minutes depending on prey size. However, these large prey are relatively hard to handle and often targeted by African fish eagle (Icthyophaga vocifer), which frequently steal large wading bird's prey.[25]

Relationship to humans

[edit]This species is considered to be one of the five most desirable birds in Africa by birdwatchers.[30] They are docile with humans and show no threatening behavior. Researchers were able to observe a bird on its nest at a close distance – within 2 meters (6 ft 7 in).[31] Shoebills are often kept in zoos, but breeding is rarely reported. Shoebills have bred successfully at Pairi Daiza in Belgium and at Tampa's Lowry Park Zoo in Florida.[32][23]

Appearances in popular culture

[edit]Beginning in 2014 and with various interspersed surges of attention since then, the shoebill has become the subject of internet memes, in part due to its intimidating appearance and its tendency to stand still for long periods of time. One such example is a video of a shoebill standing in the rain whilst staring into the camera. These memes have since also appeared on the social media platform TikTok, bringing a comparatively unknown species of bird into popular culture.[33] The shoebill also inspired the design of the Loftwing birds in the 2011 game The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword.[34][35]

Status and conservation

[edit]The population is estimated at between 5,000 and 8,000 individuals, the majority of which live in swamps in South Sudan, Uganda, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Zambia.[36] There is also a viable population in the Malagarasi wetlands in Tanzania.[37] BirdLife International has classified it as Vulnerable with the main threats being habitat destruction, disturbance and hunting. The bird is listed under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).[38] Habitat destruction and degradation, hunting, disturbance and illegal capture are all contributing factors to the decline of this species. Agriculture cultivation and pasture for cattle have also caused significant habitat loss. Indigenous communities that surround Shoebill habitats capture their eggs and chicks for human consumption and for trade. Frequent fires in southern Sudan and deliberate fires for grazing access contribute to habitat loss. Some swamps in Sudan are being drained for construction of a canal to control nearby waterways, causing more habitat loss.[32]

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Balaeniceps rex". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018 e.T22697583A133840708. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22697583A133840708.en.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Houlihan, Patrick F. (1988). The Birds of Ancient Egypt. Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-977-424-185-7.

- ^ Gould, John (1850). "Scientific: Zoological". Athenaeum (1207): 1315.

- ^ Gould, John (1851). "On a new and remarkable form in ornithology". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 19 (219): 1–2. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1851.tb01123.x.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 252–253.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Feduccia, Alan (1977). "The whalebill is a stork". Nature. 266 (5604): 719–720. Bibcode:1977Natur.266..719F. doi:10.1038/266719a0. S2CID 4260563.

- ^ a b c Elliot, A. (1992). "Family Balaenicipitidae (Shoebill)". In del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. pp. 466–471. ISBN 84-87334-10-5.

- ^ Cottam, P. A. (1957). "The Pelecaniform characters of the skeleton of the Shoebill Stork, Balaeniceps rex". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Zoology. 5: 49–72. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.11718.

- ^ Mikhailov, Konstantin E. (1995). "Eggshell structure in the shoebill and pelecaniform birds: comparison with hamerkop, herons, ibises and storks". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 73 (9): 1754–70. Bibcode:1995CaJZ...73.1754M. doi:10.1139/z95-207.

- ^ Mayr, Gerald (2003). "The phylogenetic affinities of the Shoebill (Balaeniceps rex)" (PDF). Journal für Ornithologie. 144 (2): 157–175. Bibcode:2003JOrni.144..157M. doi:10.1007/BF02465644. S2CID 36046887. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Hagey, J. R.; Schteingart, C. D.; Ton-Nu, H.-T. & Hofmann, A. F. (2002). "A novel primary bile acid in the Shoebill stork and herons and its phylogenetic significance". Journal of Lipid Research. 43 (5): 685–90. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)30109-7. PMID 11971938.

- ^ Hackett, S.J.; Kimball, R.T.; Reddy, S.; Bowie, R.C.K.; Braun, E.L.; Braun, M.J.; Chojnowski, J.L.; Cox, W.A.; Han, K-L.; Harshman, J.; Huddleston, C.J.; Marks, B.D.; Miglia, K.J.; Moore, W.S.; Sheldon, F.H.; Steadman, D.W.; Witt, C.C.; Yuri, T. (2008). "A phylogenomic study of birds reveals their evolutionary history". Science. 320 (5884): 1763–1767. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1763H. doi:10.1126/science.1157704. PMID 18583609. S2CID 6472805.

- ^ Smith, N.D.; Ksepka, D.T. (2015). "Five well-supported fossil calibrations within the "Waterbird" assemblage (Tetrapoda, Aves)". Palaeontologia Electronica. 18 (1): 1–21. doi:10.26879/483.

- ^ Rich, P.V. (1972). "A fossil avifauna from the Upper Miocene, Beglia Formation of Tunisia". Notes et mémoires du Service géologique (Tunis). 35: 29–66.

- ^ Mayr, G. (2003). "The phylogenetic affinities of the Shoebill (Balaeniceps rex)" (PDF). Journal of Ornithology. 144 (2): 157–175. Bibcode:2003JOrni.144..157M. doi:10.1007/BF02465644.

- ^ Rasmussen, D. Tab; Simons, Elwyn L.; Hertel, F.; Judd, A. (2001). "Hindlimb of a giant terrestrial bird from the Upper Eocene, Fayum, Egypt". Palaeontology. 44 (2): 325–337. Bibcode:2001Palgy..44..325R. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00182.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hancock, J.A.; Kushan, J.A.; Kahl, M.P. (1992). Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills of the World. London: Academic Press/Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers. pp. 139–145, 305. ISBN 0-12-322730-5.

- ^ Steffen, Angie. "Balaeniceps rex (shoebill)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Oeschger, E. (2004). "Sahara - Algeria - Rock Art in Oued Derat and the Tefedest Region" (PDF). Adoranten. 2004: 5–19.

- ^ Acácio, Marta; Mullers, Ralf H. E.; Franco, Aldina M. A.; Willems, Frank J.; Amar, Arjun (4 August 2021). "Changes in surface water drive the movements of Shoebills". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 15796. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1115796A. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-95093-5. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8338928. PMID 34349159.

- ^ a b Tomita, J.A.; Killmar, L.E.; Ball, R.; Rottman, L.A.; Kowitz, M. (2014). "Challenges and successes in the propagation of the Shoebill Balaeniceps rex: with detailed observations from Tampa's Lowry Park Zoo, Florida". International Zoo Yearbook. 48 (1): 69–82. doi:10.1111/izy.12038.

- ^ Mullers, Ralf H. E.; Amar, Arjun (2015). "Parental nesting behavior, chick growth and breeding success of shoebills (Balaeniceps rex) in the Bangweulu Wetlands, Zambia". Waterbirds. 38 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1675/063.038.0102. S2CID 84828980.

- ^ a b John, Jasson; Lee, Woo (2019). "Kleptoparasitism of Shoebills Balaeniceps rex by African Fish Eagles Icthyophaga vocifer in Western Tanzania". Tanzania Journal of Science. 45 (2): 131–143.

- ^ Collar, Nigel J. (1994). "The Shoebill". Bulletin of the African Bird Club. 1 (1): 18–20. doi:10.5962/p.308857.

- ^ a b Buxton, Lucinda; Slater, Jenny; Brown, Leslie H. (1978). "The breeding behaviour of the shoebill or whale-headed stork Balaeniceps rex in the Bangweulu Swamps, Zambia". African Journal of Ecology. 16 (3): 201–220. Bibcode:1978AfJEc..16..201B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1978.tb00440.x.

- ^ "Balaeniceps rex (Shoebill)". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Mullers, Ralf HE; Amar, Arjun (2015). "Shoebill Balaeniceps rex foraging behaviour in the Bangweulu Wetlands, Zambia". Ostrich. 86 (1–2): 113–118. Bibcode:2015Ostri..86..113M. doi:10.2989/00306525.2014.977364. S2CID 84194123.

- ^ Matthiessen, Peter (1991). African Silences (1st ed.). New York: Random House. p. 56. ISBN 0-679-40021-4. OCLC 22707869.

- ^ "Balaeniceps rex (shoebill)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ a b Muir, A.; King, C.E. (2013). "Management and husbandry guidelines for Shoebills Balaeniceps rex in captivity". International Zoo Yearbook. 47 (1): 181–189. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.2012.00186.x.

- ^ Vidal, Nicholas (28 March 2023). "Extinction, Climate Change and Shoebills Oh My!". The Montclarion. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ Yuste Frías, José (16 December 2014). "Traducción y paratraducción en la localización de videojuegos". Scientia Traductionis (in Spanish) (15): 72. doi:10.5007/1980-4237.2014n15p61. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

Pero por mucho que la forma del pico del ave esté inspirada en el picozapato (Shoebill en inglés, balaeniceps rex en latín), un ave de color gris del África tropical y oriental, lo que más destaca en la imagen de Loftwing no es su pico sino sus alas.

[formatting original] - ^ Miyamoto, Shigeru; Aonuma, Eiji (29 January 2013). The Legend of Zelda: Hyrule Historia. Dark Horse. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-6165-5041-7.

Loftwings are modeled after birds called shoebills [...] — Hiraoka, designer

- ^ Williams, John G.; Arlott, N (1980). A Field Guide to the Birds of East Africa (Rev. ed.). London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-219179-2. OCLC 7649557.

- ^ John, Jasson; Nahonyo, Cuthbert; Lee, Woo; Msuya, Charles (March 2013). "Observations on nesting of shoebill Balaeniceps rex and wattled crane Bugeranus carunculatus in Malagarasi wetlands, western Tanzania". African Journal of Ecology. 51 (1): 184–187. Bibcode:2013AfJEc..51..184J. doi:10.1111/aje.12023.

- ^ "Appendices I, II and III". Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. 14 October 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Guillet, A (1978). "Distribution and conservation of the Shoebill (Balaeniceps rex) in the Southern Sudan". Biological Conservation. 13 (1): 39–50. Bibcode:1978BCons..13...39G. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(78)90017-4.