Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Single-stage-to-orbit

View on Wikipedia

A single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) vehicle reaches orbit from the surface of a body using only propellants and fluids and without expending tanks, engines, or other major hardware. The term usually, but not exclusively refers to reusable vehicles.[1] To date, no Earth-launched SSTO launch vehicles have ever been flown; orbital launches from Earth have been performed by multi-stage rockets, either fully or partially expendable.

The main projected advantage of the SSTO concept is elimination of the hardware replacement inherent in expendable launch systems. However, the non-recurring costs associated with design, development, research and engineering (DDR&E) of reusable SSTO systems are much higher than expendable systems due to the substantial technical challenges of SSTO, assuming that those technical issues can in fact be solved.[2] SSTO vehicles may also require a significantly higher degree of regular maintenance.[3]

It is considered to be marginally possible to launch a single-stage-to-orbit chemically fueled spacecraft from Earth. The principal complicating factors for SSTO from Earth are: high orbital velocity of over 7,400 metres per second (27,000 km/h; 17,000 mph); the need to overcome Earth's gravity, especially in the early stages of flight; and flight within Earth's atmosphere, which limits speed in the early stages of flight due to drag, and influences engine performance.[4]

Advances in rocketry in the 21st century have resulted in a substantial fall in the cost to launch a kilogram of payload to either low Earth orbit or the International Space Station,[5] reducing the main projected advantage of the SSTO concept.

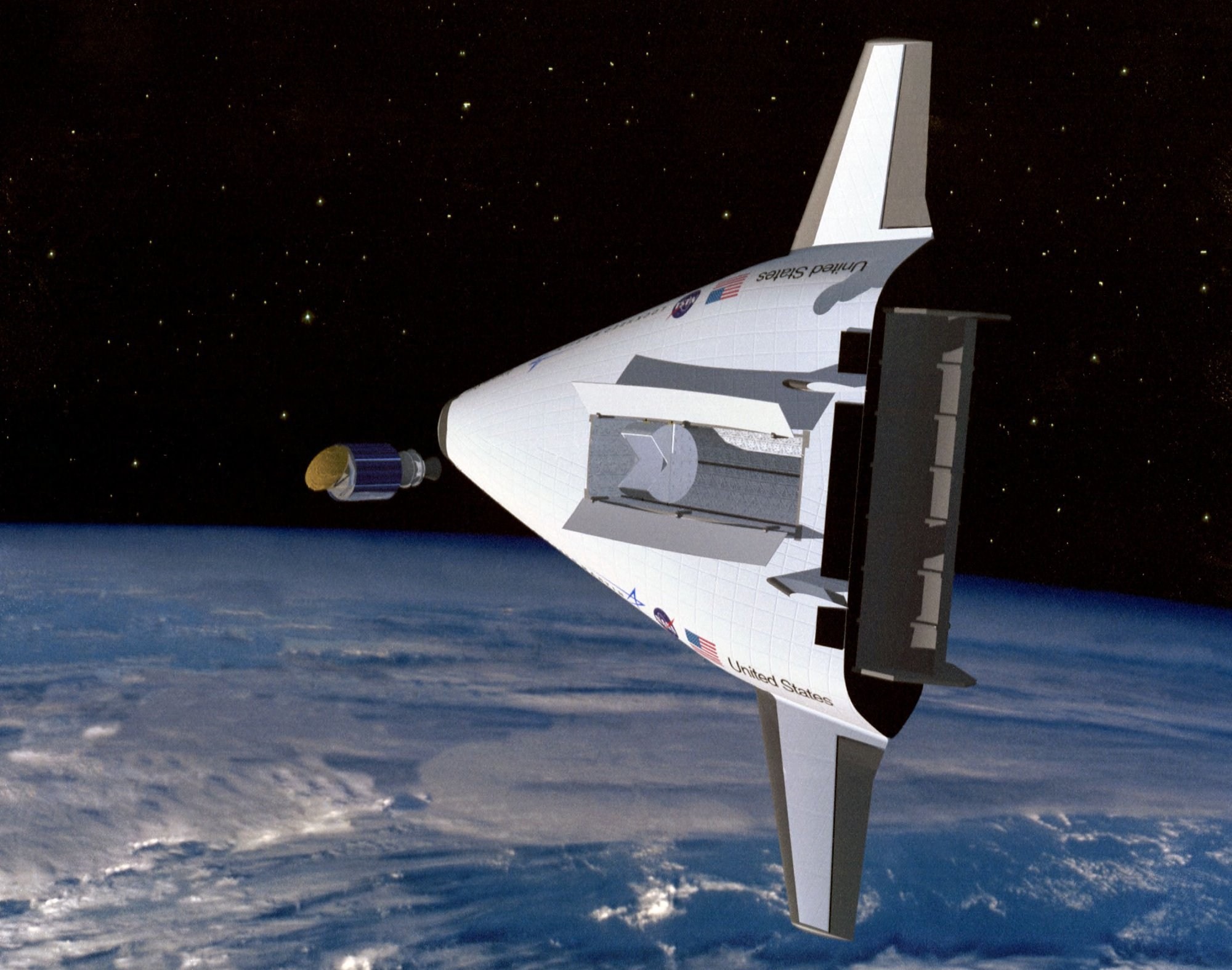

Notable single stage to orbit concepts include Skylon, which used the hybrid-cycle SABRE engine that can use oxygen from the atmosphere when it is at low altitude, and then use onboard liquid oxygen after switching to the closed cycle rocket engine at high altitude, the McDonnell Douglas DC-X, the Lockheed Martin X-33 and VentureStar which was intended to replace the Space Shuttle, and the Roton SSTO, which is a helicopter that can get to orbit. However, despite showing some promise, none of them have come close to achieving orbit yet due to problems with finding a sufficiently efficient propulsion system and discontinued development.[1]

Single-stage-to-orbit is much easier to achieve on extraterrestrial bodies that have weaker gravitational fields and lower atmospheric pressure than Earth, such as the Moon and Mars, and has been achieved from the Moon by the Apollo program's Lunar Module, by several robotic spacecraft of the Soviet Luna program, and by China's Chang'e 5 and Chang'e 6 lunar sample return missions.

History

[edit]Early concepts

[edit]

Before the second half of the twentieth century, very little research was conducted into space travel. During the 1960s, some of the first concept designs for this kind of craft began to emerge.[6]

One of the earliest SSTO concepts was the expendable One stage Orbital Space Truck (OOST) proposed by Philip Bono,[7] an engineer for Douglas Aircraft Company.[8] A reusable version named ROOST was also proposed.

Another early SSTO concept was a reusable launch vehicle named NEXUS which was proposed by Krafft Arnold Ehricke in the early 1960s. It was one of the largest spacecraft ever conceptualized with a diameter of over 50 metres and the capability to lift up to 2000 short tons into Earth orbit, intended for missions to further out locations in the Solar System such as Mars.[9][10]

The North American Air Augmented VTOVL from 1963 was a similarly large craft which would have used ramjets to decrease the liftoff mass of the vehicle by removing the need for large amounts of liquid oxygen while traveling through the atmosphere.[11]

From 1965, Robert Salkeld investigated various single stage to orbit winged spaceplane concepts. He proposed a vehicle which would burn hydrocarbon fuel while in the atmosphere and then switch to hydrogen fuel for increasing efficiency once in space.[12][13][14]

Further examples of Bono's early concepts (prior to the 1990s) which were never constructed include:

- ROMBUS (Reusable Orbital Module, Booster, and Utility Shuttle), another design from Philip Bono.[15][16] This was not technically single stage since it dropped some of its initial hydrogen tanks, but it came very close.

- Ithacus, an adapted ROMBUS concept which was designed to carry soldiers and military equipment to other continents via a sub-orbital trajectory.[17][18]

- Pegasus, another adapted ROMBUS concept designed to carry passengers and payloads long distances in short amounts of time via space.[19]

- Douglas SASSTO, a 1967 launch vehicle concept.[20]

- Hyperion, yet another Philip Bono concept which used a sled to build up speed before liftoff to save on the amount of fuel which had to be lifted into the air.[21]

Star-raker: In 1979, Rockwell International unveiled a concept for a 100-ton payload heavy-lift multicycle airbreather ramjet/cryogenic rocket engine, horizontal takeoff/horizontal landing single-stage-to-orbit spaceplane named Star-Raker, designed to launch heavy Space-based solar power satellites into a 300 nautical mile Earth orbit.[22][23][24] Star-raker would have had 3 x LOX/LH2 rocket engines (based on the SSME) + 10 x turboramjets.[22]

Around 1985 the NASP project was intended to launch a scramjet vehicle into orbit, but funding was stopped and the project cancelled.[25] At around the same time, the HOTOL tried to use precooled jet engine technology, but failed to show significant advantages over rocket technology.[26]

DC-X technology

[edit]

The DC-X, short for Delta Clipper Experimental, was an uncrewed one-third scale vertical takeoff and landing demonstrator for a proposed SSTO. It is one of only a few prototype SSTO vehicles ever built. Several other prototypes were intended, including the DC-X2 (a half-scale prototype) and the DC-Y, a full-scale vehicle which would be capable of single stage insertion into orbit. Neither of these were built, but the project was taken over by NASA in 1995, and they built the DC-XA, an upgraded one-third scale prototype. This vehicle was lost when it landed with only three of its four landing pads deployed, which caused it to tip over on its side and explode. The project has not been continued since.[citation needed]

Roton

[edit]From 1999 to 2001 Rotary Rocket attempted to build a SSTO vehicle called the Roton. It received a large amount of media attention and a working sub-scale prototype was completed, but the design was largely impractical.[27]

Approaches

[edit]There have been various approaches to SSTO vehicles including: pure rockets that are launched and land vertically, air-breathing scramjet-powered vehicles that are launched and land horizontally, nuclear-powered vehicles, and even jet-engine-powered vehicles that can fly into orbit and return landing like an airliner, completely intact.

For rocket-powered SSTO, the main challenge is achieving a high enough mass-ratio to carry sufficient propellant to achieve orbit, plus a meaningful payload weight. One possibility is to give the rocket an initial speed with a space gun, as planned in the Quicklaunch project.[28]

For air-breathing SSTO, the main challenges are system complexity and associated research and development costs, material science, construction techniques necessary for surviving sustained high-speed flight within the atmosphere, and achieving a high enough mass-ratio to carry sufficient propellant to achieve orbit, plus a meaningful payload weight. Air-breathing designs typically fly at supersonic or hypersonic speeds and usually include a rocket engine for the final burn for orbit.[1]

Whether rocket-powered or air-breathing, a reusable vehicle must be rugged enough to survive multiple round trips into space without adding excessive weight or maintenance. In addition, a reusable vehicle must be able to reenter without damage and land safely.[citation needed]

While single-stage rockets were once thought to be beyond reach, advances in materials technology and construction techniques have shown them to be possible. For example, calculations show that the Titan II first stage, launched on its own, would have a 25-to-1 ratio of fuel to vehicle hardware.[29] It has a sufficiently efficient engine to achieve orbit, but without carrying much payload.[30]

Dense versus hydrogen fuels

[edit]Hydrogen fuel might seem the obvious fuel for SSTO vehicles. When burned with oxygen, hydrogen gives the highest specific impulse of any commonly used fuel: around 450 seconds,[31] compared with up to 350 seconds[32] for kerosene.

Hydrogen has the following advantages:[citation needed]

- Hydrogen has nearly 30% higher specific impulse (about 450 seconds vs. 350 seconds) than most dense fuels.

- Hydrogen is an excellent coolant.

- The gross mass of hydrogen stages is lower than dense-fuelled stages for the same payload.

- Hydrogen is environmentally friendly.

However, hydrogen also has these disadvantages:[citation needed]

- Very low density (about 1⁄7 of the density of kerosene) – requiring a very large tank

- Deeply cryogenic – must be stored at very low temperatures and thus needs heavy insulation

- Escapes very easily from the smallest gap

- Wide combustible range – easily ignited and burns with a dangerously invisible flame

- Tends to condense oxygen which can cause flammability problems

- Has a large coefficient of expansion for even small heat leaks.

These issues can be dealt with, but at extra cost.[citation needed]

While kerosene tanks can be 1% of the weight of their contents, hydrogen tanks often must weigh 10% of their contents. This is because of both the low density and the additional insulation required to minimize boiloff (a problem which does not occur with kerosene and many other fuels). The low density of hydrogen further affects the design of the rest of the vehicle: pumps and pipework need to be much larger in order to pump the fuel to the engine. The result is the thrust/weight ratio of hydrogen-fueled engines is 30–50% lower than comparable engines using denser fuels.[citation needed]

This inefficiency indirectly affects gravity losses as well; the vehicle has to hold itself up on rocket power until it reaches orbit. The lower excess thrust of the hydrogen engines due to the lower thrust/weight ratio means that the vehicle must ascend more steeply, and so less thrust acts horizontally. Less horizontal thrust results in taking longer to reach orbit, and gravity losses are increased by at least 300 metres per second (1,100 km/h; 670 mph). While not appearing large, the mass ratio to delta-v curve is very steep to reach orbit in a single stage, and this makes a 10% difference to the mass ratio on top of the tankage and pump savings.[citation needed]

The overall effect is that there is surprisingly little difference in overall performance between SSTOs that use hydrogen and those that use denser fuels, except that hydrogen vehicles may be rather more expensive to develop and buy. Careful studies have shown that some dense fuels (for example liquid propane) exceed the performance of hydrogen fuel when used in an SSTO launch vehicle by 10% for the same dry weight.[33]

In the 1960s Philip Bono investigated single-stage, VTVL tripropellant rockets, and showed that it could improve payload size by around 30%.[34]

Operational experience with the DC-X experimental rocket has caused a number of SSTO advocates to reconsider hydrogen as a satisfactory fuel. The late Max Hunter, while employing hydrogen fuel in the DC-X, often said that he thought the first successful orbital SSTO would more likely be fueled by propane.[citation needed]

One engine for all altitudes

[edit]Some SSTO concepts use the same engine for all altitudes, which is a problem for traditional engines with a bell-shaped nozzle. Depending on the atmospheric pressure, different bell shapes are required. Engines designed to operate in a vacuum have large bells, allowing the exhaust gasses to expand to near vacuum pressures, thereby raising efficiency.[35] Due to an effect known as Flow separation, using a vacuum bell in atmosphere would have disastrous consequences for the engine. Engines designed to fire in atmosphere therefore have to shorten the nozzle, only expanding the gasses to atmospheric pressure. The efficiency losses due to the smaller bell are usually mitigated via staging, as upper stage engines such as the Rocketdyne J-2 do not have to fire until atmospheric pressure is negligible, and can therefore use the larger bell.

One possible solution would be to use an aerospike engine, which can be effective in a wide range of ambient pressures. In fact, a linear aerospike engine was to be used in the X-33 design.[36]

Other solutions involve using multiple engines and other altitude adapting designs such as double-mu bells or extensible bell sections.[citation needed]

Still, at very high altitudes, the extremely large engine bells tend to expand the exhaust gases down to near vacuum pressures. As a result, these engine bells are counterproductive[dubious – discuss] due to their excess weight. Some SSTO concepts use very high pressure engines which permit high ratios to be used from ground level. This gives good performance, negating the need for more complex solutions.[citation needed]

Airbreathing SSTO

[edit]

Some designs for SSTO attempt to use airbreathing jet engines that collect oxidizer and reaction mass from the atmosphere to reduce the take-off weight of the vehicle.[37]

Some of the issues with this approach are:[citation needed]

- No known air breathing engine is capable of operating at orbital speed within the atmosphere (for example hydrogen fueled scramjets seem to have a top speed of about Mach 17).[38] This means that rockets must be used for the final orbital insertion.

- Rocket thrust needs the orbital mass to be as small as possible to minimize propellant weight.

- The thrust-to-weight ratio of rockets that rely on on-board oxygen increases dramatically as fuel is expended, because the oxidizer fuel tank has about 1% of the mass as the oxidizer it carries, whereas air-breathing engines traditionally have a poor thrust/weight ratio which is relatively fixed during the air-breathing ascent.

- Very high speeds in the atmosphere necessitate very heavy thermal protection systems, which makes reaching orbit even harder.

- While at lower speeds, air-breathing engines are very efficient, but the efficiency (Isp) and thrust levels of air-breathing jet engines drop considerably at high speed (above Mach 5–10 depending on the engine) and begin to approach that of rocket engines or worse.

- Lift to drag ratios of vehicles at hypersonic speeds are poor, however the effective lift to drag ratios of rocket vehicles at high g is not dissimilar.

Thus with for example scramjet designs (e.g. X-43) the mass budgets do not seem to close for orbital launch.[citation needed]

Similar issues occur with single-stage vehicles attempting to carry conventional jet engines to orbit—the weight of the jet engines is not compensated sufficiently by the reduction in propellant.[39]

On the other hand, LACE-like precooled airbreathing designs such as the Skylon spaceplane (and ATREX) which transition to rocket thrust at rather lower speeds (Mach 5.5) do seem to give, on paper at least, an improved orbital mass fraction over pure rockets (even multistage rockets) sufficiently to hold out the possibility of full reusability with better payload fraction.[40]

It is important to note that mass fraction is an important concept in the engineering of a rocket. However, mass fraction may have little to do with the costs of a rocket, as the costs of fuel are very small when compared to the costs of the engineering program as a whole. As a result, a cheap rocket with a poor mass fraction may be able to deliver more payload to orbit with a given amount of money than a more complicated, more efficient rocket.[citation needed]

Launch assists

[edit]Many vehicles are only narrowly suborbital, so practically anything that gives a relatively small delta-v increase can be helpful, and outside assistance for a vehicle is therefore desirable.[citation needed]

Proposed launch assists include:[citation needed]

- sled launch (rail, maglev including Bantam, MagLifter, and StarTram, etc.)[41]

- air launch or aircraft tow

- aerial refueling

- Lofstrom launch loop/space fountains

And on-orbit resources such as:[citation needed]

- Space tether

- tugs

Nuclear propulsion

[edit]Due to weight issues such as shielding, many nuclear propulsion systems are unable to lift their own weight, and hence are unsuitable for launching to orbit. However, some designs such as the Orion project and some nuclear thermal designs do have a thrust to weight ratio in excess of 1, enabling them to lift off. Clearly, one of the main issues with nuclear propulsion would be safety, both during a launch for the passengers, but also in case of a failure during launch. As of February 2024, no current program is attempting nuclear propulsion from Earth's surface.[citation needed]

Beam-powered propulsion

[edit]Because they can be more energetic than the potential energy that chemical fuel allows for, some laser or microwave powered rocket concepts have the potential to launch vehicles into orbit, single stage. In practice, this area is not possible with current technology.[citation needed]

Design challenges inherent in SSTO

[edit]The design space constraints of SSTO vehicles were described by rocket design engineer Robert Truax:

Using similar technologies (i.e., the same propellants and structural fraction), a two-stage-to-orbit vehicle will always have a better payload-to-weight ratio than a single stage designed for the same mission, in most cases, a very much better [payload-to-weight ratio]. Only when the structural factor approaches zero [very little vehicle structure weight] does the payload/weight ratio of a single-stage rocket approach that of a two-stage. A slight miscalculation and the single-stage rocket winds up with no payload. To get any at all, technology needs to be stretched to the limit. Squeezing out the last drop of specific impulse, and shaving off the last pound, costs money and/or reduces reliability.[42]

The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation expresses the maximum change in velocity any single rocket stage can achieve:

where:

The mass ratio of a vehicle is defined as a ratio the initial vehicle mass when fully loaded with propellants to the final vehicle mass after the burn:

where:

The propellant mass fraction () of a vehicle can be expressed solely as a function of the mass ratio:

The structural coefficient () is a critical parameter in SSTO vehicle design.[43] Structural efficiency of a vehicle is maximized as the structural coefficient approaches zero. The structural coefficient is defined as:

The overall structural mass fraction can be expressed in terms of the structural coefficient:

An additional expression for the overall structural mass fraction can be found by noting that the payload mass fraction , propellant mass fraction and structural mass fraction sum to one:

Equating the expressions for structural mass fraction and solving for the initial vehicle mass yields:

This expression shows how the size of a SSTO vehicle is dependent on its structural efficiency. Given a mission profile and propellant type , the size of a vehicle increases with an increasing structural coefficient.[44] This growth factor sensitivity is shown parametrically for both SSTO and two-stage-to-orbit (TSTO) vehicles for a standard LEO mission.[45] The curves vertically asymptote at the maximum structural coefficient limit where mission criteria can no longer be met:

In comparison to a non-optimized TSTO vehicle using restricted staging, a SSTO rocket launching an identical payload mass and using the same propellants will always require a substantially smaller structural coefficient to achieve the same delta-v. Given that current materials technology places a lower limit of approximately 0.1 on the smallest structural coefficients attainable,[46] reusable SSTO vehicles are typically an impractical choice even when using the highest performance propellants available.

Examples

[edit]It is easier to achieve SSTO from a body with lower gravitational pull than Earth, such as the Moon or Mars. The Apollo Lunar Module ascended from the lunar surface to lunar orbit in a single stage.[47]

A detailed study into SSTO vehicles was prepared by Chrysler Corporation's Space Division in 1970–1971 under NASA contract NAS8-26341. Their proposal (Shuttle SERV) was an enormous vehicle with more than 50,000 kilograms (110,000 lb) of payload, utilizing jet engines for (vertical) landing.[48] While the technical problems seemed to be solvable, the USAF required a winged design that led to the Shuttle as we know it today.

The uncrewed DC-X technology demonstrator, originally developed by McDonnell Douglas for the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) program office, was an attempt to build a vehicle that could lead to an SSTO vehicle. The one-third-size test craft was operated and maintained by a small team of three people based out of a trailer, and the craft was once relaunched less than 24 hours after landing. Although the test program was not without mishap (including a minor explosion), the DC-X demonstrated that the maintenance aspects of the concept were sound. That project was cancelled when it landed with three of four legs deployed, tipped over, and exploded on the fourth flight after transferring management from the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization to NASA.[citation needed]

The Aquarius Launch Vehicle was designed to bring bulk materials to orbit as cheaply as possible.[citation needed]

Current development

[edit]Current and previous SSTO projects include the Japanese Kankoh-maru project, ARCA Haas 2C, Radian One and the Indian Avatar spaceplane.[citation needed]

Skylon

[edit]The British Government partnered with the ESA in 2010 to promote a single-stage to orbit spaceplane concept called Skylon.[49] This design was pioneered by Reaction Engines Limited (REL),[50][51] a company founded by Alan Bond after HOTOL was canceled.[52] The Skylon spaceplane has been positively received by the British government, and the British Interplanetary Society.[53] Following a successful propulsion system test that was audited by ESA's propulsion division in mid-2012, REL announced that it would begin a three-and-a-half-year project to develop and build a test jig of the Sabre engine to prove the engines performance across its air-breathing and rocket modes.[54] In November 2012, it was announced that a key test of the engine precooler had been successfully completed, and that ESA had verified the precooler's design. The project's development is now allowed to advance to its next phase, which involves the construction and testing of a full-scale prototype engine.[54][55]

Alternative approaches to inexpensive spaceflight

[edit]Many studies have shown that regardless of selected technology, the most effective cost reduction technique is economies of scale.[citation needed] Merely launching a large total number reduces the manufacturing costs per vehicle, similar to how the mass production of automobiles brought about great increases in affordability.[citation needed]

Using this concept, some aerospace analysts believe the way to lower launch costs is the exact opposite of SSTO. Whereas reusable SSTOs would reduce per launch costs by making a reusable high-tech vehicle that launches frequently with low maintenance, the "mass production" approach views the technical advances as a source of the cost problem in the first place. By simply building and launching large quantities of rockets, and hence launching a large volume of payload, costs can be brought down. This approach was attempted in the late 1970s, early 1980s in West Germany with the Democratic Republic of the Congo-based OTRAG rocket.[56]

This is somewhat similar to the approach some previous systems have taken, using simple engine systems with "low-tech" fuels, as the Russian and Chinese space programs still do.[citation needed]

An alternative to scale is to make the discarded stages practically reusable: this was the original design goal of the Space Shuttle phase B studies, and is currently pursued by the SpaceX reusable launch system development program with their Falcon 9, Falcon Heavy, and Starship, and Blue Origin using New Glenn.

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Andrew J. Butrica: Single Stage to Orbit - Politics, Space Technology, and the Quest for Reusable Rocketry. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2004, ISBN 9780801873386.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Richard Varvill & Alan Bond (2003). "A Comparison of Propulsion Concepts for SSTO Reusable Launchers" (PDF). JBIS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ Dick, Stephen and Lannius, R., "Critical Issues in the History of Spaceflight," NASA Publication SP-2006-4702, 2006.

- ^ Koelle, Dietrich E. (1 July 1993). "Cost analysis for single-stage (SSTO) reusable ballistic launch vehicles". Acta Astronautica. 30: 415–421. Bibcode:1993AcAau..30..415K. doi:10.1016/0094-5765(93)90132-G. ISSN 0094-5765. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Toso, Federico. "DEPLOYED PAYLOAD ANALYSIS FOR A SINGLE STAGE TO ORBIT SPACEPLANE" (PDF). Centre for Future Air Space Transportation Technologies: 1.

- ^ Jones, Harry W. (8 July 2018). "The Recent Large Reduction in Space Launch Cost". International Conference on Environmental Systems. Archived from the original on 24 January 2025. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ Gomersall, Edward (20 July 1970). A Single Stage To Orbit Shuttle Concept. Ames Mission Analysis Division Office of Advanced Research and Technology: NASA. p. 54. N93-71495.

- ^ Philip Bono and Kenneth William Gatland, Frontiers of Space, ISBN 0-7137-3504-X

- ^ Wade, Mark. "OOST". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Aerospace projects Review (Report). Vol. 3. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ "SP-4221 The Space Shuttle Decision". NASA History. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Astronautica - North American Air Augmented VTOVL". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ "Salkeld Shuttle". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "ROBERT SALKELD'S". pmview.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "STS-1 Further Reading". nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ Bono, Philip (June 1963). "ROMBUS - An Integrated Systems Concept for a Reusable Orbital Module/Booster And Utility Shuttle". AIAA (AIAA-1963-271). Archived from the original on 16 December 2008.

- ^ "Rombus". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008.

- ^ Bono, Philip (June 1963). ""Ithacus" — a new concept of inter-continental ballistic transport (ICBT)". AIAA (AIAA-1964-280). Archived from the original on 16 December 2008.

- ^ "Ithacus". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2002.

- ^ "Pegasus VTOVL". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ "SASSTO". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008.

- ^ "Hyperion SSTO". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Star-raker". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ "The Space Plane NASA Wanted to Use to Build Solar Power Plants in Orbit". Vice.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ "Star Raker An Airbreather/Rocket-Powered, Horizontal Takeoff Tridelta Flying Wing, Single-Stage-to-Orbit Transportation System" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ "X-30". 29 August 2002. Archived from the original on 29 August 2002.

- ^ Moxon, Julian (1 March 1986), "Hotol: where next?", Flight International, vol. 129, no. 4000, Business Press International, pp. 38–40, ISSN 0015-3710, archived from the original on 22 October 2012 – via FlightGlobal Archive

- ^ "Wired 4.05: Insanely Great? or Just Plain Insane?". wired.com. May 1996. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "A Cannon for Shooting Supplies into Space". Popular Science. 15 January 2010. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "The titan family". Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ^ Mitchell Burnside-Clapp (February 1997). "A LO2/Kerosene SSTO Rocket Design". Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ^ "RS-25 Engine". Aerojet Rocketdyne. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014.

- ^ Wade, Mark. "RD-170". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 15 April 2002. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Dr. Bruce Dunn (1996). "Alternate Propellants for SSTO Launchers". Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ^ "VTOVL". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "Nozzle Design". www.grc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Monroe, Conner (30 March 2016). "Lockheed Martin X-33". NASA. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "SABRE :: Reaction Engines". www.reactionengines.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Mark Wade (2007). "X-30". Archived from the original on 29 August 2002. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ^ Richard Varvill & Alan Bond (2003). "A Comparison of Propulsions Concepts for SSTO Reusable launchers" (PDF). Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. pp. 108–117. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ^ Cimino, P.; Drake, J.; Jones, J.; Strayer, D.; Venetoklis, P.: "Transatmospheric vehicle propelled by air-turborocket engines" Archived 1 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, AIAA, Joint Propulsion Conference, 21st, Monterey, CA, 8–11 July 1985. 10 p. Research supported by the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute., 07/1985

- ^ "High-elevation equatorial catapult-launched RBCC SSTO spaceplane for economic manned access to LEO". Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ London III, Lt Col John R., "LEO on the Cheap", Air University (AFMC) Research Report No. AU-ARI-93-8, October 1994.

- ^ Hale, Francis, Introduction to Space Flight, Prentice Hall, 1994.

- ^ Mossman, Jason, "Investigation of Advanced Propellants to Enable Single Stage to Orbit Launch Vehicles", Master's thesis, California State University, Fresno, 2006.

- ^ Livington, J.W., "Comparative Analysis of Rocket and Air-Breathing Launch Vehicle Systems", Space 2004 Conference and Exhibit, San Diego, California, 2004.

- ^ Curtis, Howard, Orbital Mechanics for Engineering Students, Third Edition, Oxford: Elsevier, 2010. Print.

- ^ "Apollo 11 Lunar Module / EASEP". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Mark Wade (2007). "Shuttle SERV". Archived from the original on 7 April 2004. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ "UKSA Reviews Skylon and SABRE at Parabolic Arc". parabolicarc.com. 22 September 2010. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "Reaction Engines Ltd - Frequently Asked Questions". reactionengines.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "UK Space Agency - Skylon System Requirements Review". Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ "Reaction Engines Limited". reactionengines.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ Robert Parkinson (22 February 2011). "SSTO spaceplane is coming to Great Britain". The Global Herald. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Skylon spaceplane engine concept achieves key milestone". BBC. 28 November 2012. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Thomson, Ian. "European Space Agency clears SABRE orbital engines" Archived 1 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Register. 29 November 2012.

- ^ "Otrag". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

External links

[edit]- A Single-Stage-to-Orbit Thought Experiment Archived 15 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Why are launch costs so high?, an analysis of space launch costs, with a section critiquing SSTO

- The Cold Equations Of Spaceflight A critique of SSTO by Jeffrey F. Bell.

- Burnout Velocity Vb of a Single 1-Stage Rocket