Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tsiolkovsky rocket equation

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Astrodynamics |

|---|

The classical rocket equation, or ideal rocket equation is a mathematical equation that describes the motion of vehicles that follow the basic principle of a rocket: a device that can apply acceleration to itself using thrust by expelling part of its mass with high velocity and can thereby move due to the conservation of momentum. It is credited to Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who independently derived it and published it in 1903,[1][2] although it had been independently derived and published by William Moore in 1810,[3] and later published in a separate book in 1813.[4] Robert Goddard also developed it independently in 1912, and Hermann Oberth derived it independently about 1920.

The maximum change of velocity of the vehicle, (with no external forces acting) is:

where:

- is the effective exhaust velocity (which is also equal to )

- is the specific impulse in dimension of time;

- is standard gravity;

- is the natural logarithm function;

- is the initial total mass, including propellant, a.k.a. wet mass;

- is the final total mass without propellant, a.k.a. dry mass.

Given the effective exhaust velocity determined by the rocket motor's design, the desired delta-v (e.g., orbital speed or escape velocity), and a given dry mass , the equation can be solved for the required wet mass : The required propellant mass is then

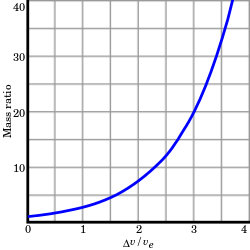

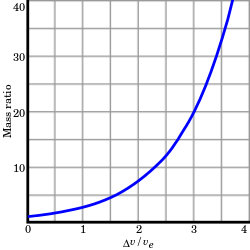

The necessary wet mass grows exponentially with the desired delta-v.

History

[edit]The equation is named after Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky who independently derived it and published it in his 1903 work.[1][2]

The equation had been derived earlier by the British mathematician William Moore in 1810,[3] and later published in a separate book in 1813.[4]

American Robert Goddard independently developed the equation in 1912 when he began his research to improve rocket engines for possible space flight. German engineer Hermann Oberth independently derived the equation about 1920 as he studied the feasibility of space travel.

While the derivation of the rocket equation is a straightforward calculus exercise, Tsiolkovsky is honored as being the first to apply it to the question of whether rockets could achieve speeds necessary for space travel.

Experiment of the boat

[edit]

In order to understand the principle of rocket propulsion, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky proposed the famous experiment of "the boat".[citation needed] A person is in a boat away from the shore without oars. They want to reach this shore. They notice that the boat is loaded with a certain quantity of stones and have the idea of quickly and repeatedly throwing the stones in succession in the opposite direction. Effectively, the quantity of movement of the stones thrown in one direction corresponds to an equal quantity of movement for the boat in the other direction (ignoring friction / drag).

Derivation

[edit]Most popular derivation

[edit]Consider the following system:

In the following derivation, "the rocket" is taken to mean "the rocket and all of its unexpended propellant".

Newton's second law of motion relates external forces () to the change in linear momentum of the whole system (including rocket and exhaust) as follows: where is the momentum of the rocket at time : and is the momentum of the rocket and exhausted mass at time : and where, with respect to the observer:

- is the velocity of the rocket at time

- is the velocity of the rocket at time

- is the velocity of the mass added to the exhaust (and lost by the rocket) during time

- is the mass of the rocket at time

- is the mass of the rocket at time

The velocity of the exhaust in the observer frame is related to the velocity of the exhaust in the rocket frame by: thus, Solving this yields: If and are opposite, have the same direction as , are negligible (since ), and using (since ejecting a positive results in a decrease in rocket mass in time),

If there are no external forces then (conservation of linear momentum) and

Assuming that is constant (known as Tsiolkovsky's hypothesis[2]), so it is not subject to integration, then the above equation may be integrated as follows:

This then yields or equivalently or or where is the initial total mass including propellant, the final mass, and the velocity of the rocket exhaust with respect to the rocket (the specific impulse, or, if measured in time, that multiplied by gravity-on-Earth acceleration). If is NOT constant, we might not have rocket equations that are as simple as the above forms. Many rocket dynamics researches were based on the Tsiolkovsky's constant hypothesis.

The value is the total working mass of propellant expended.

(delta-v) is the integration over time of the magnitude of the acceleration produced by using the rocket engine (what would be the actual acceleration if external forces were absent). In free space, for the case of acceleration in the direction of the velocity, this is the increase of the speed. In the case of an acceleration in opposite direction (deceleration) it is the decrease of the speed. Of course gravity and drag also accelerate the vehicle, and they can add or subtract to the change in velocity experienced by the vehicle. Hence delta-v may not always be the actual change in speed or velocity of the vehicle.

Other derivations

[edit]Impulse-based

[edit]The equation can also be derived from the basic integral of acceleration in the form of force (thrust) over mass. By representing the delta-v equation as the following:

where T is thrust, is the initial (wet) mass and is the initial mass minus the final (dry) mass,

and realising that the integral of a resultant force over time is total impulse, assuming thrust is the only force involved,

The integral is found to be:

Realising that impulse over the change in mass is equivalent to force over propellant mass flow rate (p), which is itself equivalent to exhaust velocity, the integral can be equated to

Acceleration-based

[edit]Imagine a rocket at rest in space with no forces exerted on it (Newton's first law of motion). From the moment its engine is started (clock set to 0) the rocket expels gas mass at a constant mass flow rate R (kg/s) and at exhaust velocity relative to the rocket ve (m/s). This creates a constant force F propelling the rocket that is equal to R × ve. The rocket is subject to a constant force, but its total mass is decreasing steadily because it is expelling gas. According to Newton's second law of motion, its acceleration at any time t is its propelling force F divided by its current mass m:

Now, the mass of fuel the rocket initially has on board is equal to m0 – mf. For the constant mass flow rate R it will therefore take a time T = (m0 – mf)/R to burn all this fuel. Integrating both sides of the equation with respect to time from 0 to T (and noting that R = dm/dt allows a substitution on the right) obtains:

Limit of finite mass "pellet" expulsion

[edit]The rocket equation can also be derived as the limiting case of the speed change for a rocket that expels its fuel in the form of pellets consecutively, as , with an effective exhaust speed such that the mechanical energy gained per unit fuel mass is given by .

In the rocket's center-of-mass frame, if a pellet of mass is ejected at speed and the remaining mass of the rocket is , the amount of energy converted to increase the rocket's and pellet's kinetic energy is

Using momentum conservation in the rocket's frame just prior to ejection, , from which we find

Let be the initial fuel mass fraction on board and the initial fueled-up mass of the rocket. Divide the total mass of fuel into discrete pellets each of mass . The remaining mass of the rocket after ejecting pellets is then . The overall speed change after ejecting pellets is the sum [5]

Notice that for large the last term in the denominator and can be neglected to give where and .

As this Riemann sum becomes the definite integral since the final remaining mass of the rocket is .

Special relativity

[edit]If special relativity is taken into account, the following equation can be derived for a relativistic rocket,[6] with again standing for the rocket's final velocity (after expelling all its reaction mass and being reduced to a rest mass of ) in the inertial frame of reference where the rocket started at rest (with the rest mass including fuel being initially), and standing for the speed of light in vacuum:

Writing as allows this equation to be rearranged as

Then, using the identity (here "exp" denotes the exponential function; see also Natural logarithm as well as the "power" identity at logarithmic identities) and the identity (see Hyperbolic function), this is equivalent to

Terms of the equation

[edit]Delta-v

[edit]Delta-v (literally "change in velocity"), symbolised as Δv and pronounced delta-vee, as used in spacecraft flight dynamics, is a measure of the impulse that is needed to perform a maneuver such as launching from, or landing on a planet or moon, or an in-space orbital maneuver. It is a scalar that has the units of speed. As used in this context, it is not the same as the physical change in velocity of the vehicle.

Delta-v is produced by reaction engines, such as rocket engines, is proportional to the thrust per unit mass and burn time, and is used to determine the mass of propellant required for the given manoeuvre through the rocket equation.

For multiple manoeuvres, delta-v sums linearly.

For interplanetary missions delta-v is often plotted on a porkchop plot which displays the required mission delta-v as a function of launch date.

Mass fraction

[edit]In aerospace engineering, the propellant mass fraction is the portion of a vehicle's mass which does not reach the destination and is instead burned as propellant, usually used as a measure of the vehicle's performance. In other words, the propellant mass fraction is the ratio between the propellant mass and the initial mass of the vehicle. In a spacecraft, the destination is usually an orbit, while for aircraft it is their landing location. A higher mass fraction represents less weight in a design. Another related measure is the payload fraction, which is the fraction of initial weight that is payload.

While the original wording of the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation does not directly use the mass fraction, the mass fraction can be derived from the used ratio of initial to final mass, or .

Effective exhaust velocity

[edit]The effective exhaust velocity is often specified as a specific impulse and they are related to each other by: where

- is the specific impulse in seconds,

- is the specific impulse measured in m/s, which is the same as the effective exhaust velocity measured in m/s (or ft/s if g is in ft/s2),

- is the standard gravity, 9.80665 m/s2 (in Imperial units 32.174 ft/s2).

Applicability

[edit]The rocket equation captures the essentials of rocket flight physics in a single short equation. It also holds true for rocket-like reaction vehicles whenever the effective exhaust velocity is constant, and can be summed or integrated when the effective exhaust velocity varies. The rocket equation only accounts for the reaction force from the rocket engine; it does not include other forces that may act on a rocket, such as aerodynamic or gravitational forces. As such, when using it to calculate the propellant requirement for launch from (or powered descent to) a planet with an atmosphere, the effects of these forces must be included in the delta-V requirement (see Examples below). In what has been called "the tyranny of the rocket equation", there is a limit to the amount of payload that the rocket can carry, as higher amounts of propellant increment the overall weight, and thus also increase the fuel consumption.[7] The equation does not apply to non-rocket systems such as aerobraking, gun launches, space elevators, launch loops, tether propulsion or light sails.

The rocket equation can be applied to orbital maneuvers in order to determine how much propellant is needed to change to a particular new orbit, or to find the new orbit as the result of a particular propellant burn. When applying to orbital maneuvers, one assumes an impulsive maneuver, in which the propellant is discharged and delta-v applied instantaneously. This assumption is relatively accurate for short-duration burns such as for mid-course corrections and orbital insertion maneuvers. As the burn duration increases, the result is less accurate due to the effect of gravity on the vehicle over the duration of the maneuver. For low-thrust, long duration propulsion, such as electric propulsion, more complicated analysis based on the propagation of the spacecraft's state vector and the integration of thrust are used to predict orbital motion.

Examples

[edit]Assume an exhaust velocity of 4,500 meters per second (15,000 ft/s) and a of 9,700 meters per second (32,000 ft/s) (Earth to LEO, including to overcome gravity and aerodynamic drag).

- Single-stage-to-orbit rocket: = 0.884, therefore 88.4% of the initial total mass has to be propellant. The remaining 11.6% is for the engines, the tank, and the payload.

- Two-stage-to-orbit: suppose that the first stage should provide a of 5,000 meters per second (16,000 ft/s); = 0.671, therefore 67.1% of the initial total mass has to be propellant to the first stage. The remaining mass is 32.9%. After disposing of the first stage, a mass remains equal to this 32.9%, minus the mass of the tank and engines of the first stage. Assume that this is 8% of the initial total mass, then 24.9% remains. The second stage should provide a of 4,700 meters per second (15,000 ft/s); = 0.648, therefore 64.8% of the remaining mass has to be propellant, which is 16.2% of the original total mass, and 8.7% remains for the tank and engines of the second stage, the payload, and in the case of a space shuttle, also the orbiter. Thus together 16.7% of the original launch mass is available for all engines, the tanks, and payload.

Stages

[edit]In the case of sequentially thrusting rocket stages, the equation applies for each stage, where for each stage the initial mass in the equation is the total mass of the rocket after discarding the previous stage, and the final mass in the equation is the total mass of the rocket just before discarding the stage concerned. For each stage the specific impulse may be different.

For example, if 80% of the mass of a rocket is the fuel of the first stage, and 10% is the dry mass of the first stage, and 10% is the remaining rocket, then

With three similar, subsequently smaller stages with the same for each stage, gives:

and the payload is 10% × 10% × 10% = 0.1% of the initial mass.

A comparable SSTO rocket, also with a 0.1% payload, could have a mass of 11.1% for fuel tanks and engines, and 88.8% for fuel. This would give

If the motor of a new stage is ignited before the previous stage has been discarded and the simultaneously working motors have a different specific impulse (as is often the case with solid rocket boosters and a liquid-fuel stage), the situation is more complicated.

See also

[edit]- Delta-v budget

- Jeep problem

- Mass ratio

- Oberth effect - applying delta-v in a gravity well increases the final velocity

- Relativistic rocket

- Reversibility of orbits

- Robert H. Goddard - added terms for gravity and drag in vertical flight

- Spacecraft propulsion

- Stigler’s law of eponymy

References

[edit]- ^ a b К. Ціолковскій, Изслѣдованіе мировыхъ пространствъ реактивными приборами, 1903 (available online here Archived 2011-08-15 at the Wayback Machine in a RARed PDF)

- ^ a b c Tsiolkovsky, K. "Reactive Flying Machines" (PDF).

- ^ a b Moore, William (1810). "On the Motion of Rockets both in Nonresisting and Resisting Mediums". Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry & the Arts. 27: 276–285.

- ^ a b Moore, William (1813). A Treatise on the Motion of Rockets: to which is added, an Essay on Naval Gunnery, in theory and practice, etc. G. & S. Robinson.

- ^ Blanco, Philip (November 2019). "A discrete, energetic approach to rocket propulsion". Physics Education. 54 (6): 065001. Bibcode:2019PhyEd..54f5001B. doi:10.1088/1361-6552/ab315b. S2CID 202130640.

- ^ Forward, Robert L. "A Transparent Derivation of the Relativistic Rocket Equation" (see the right side of equation 15 on the last page, with R as the ratio of initial to final mass and w as the exhaust velocity, corresponding to ve in the notation of this article)

- ^ "The Tyranny of the Rocket Equation". NASA.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-03-06. Retrieved 2016-04-18.

External links

[edit]Tsiolkovsky rocket equation

View on GrokipediaHistorical Background

Development and Naming

The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation originated from the work of Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who independently derived it in 1903 as part of his pioneering studies on space travel using reactive propulsion. Tsiolkovsky, a self-taught physicist and educator, developed the equation to quantify the velocity change achievable by a rocket expelling mass, laying foundational principles for astronautics.[1] The equation first appeared in Tsiolkovsky's seminal paper titled "Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices," published in the Russian journal Nauchnoye Obozreniye (Science Review).[5] In this work, he outlined the theoretical framework for interplanetary flight, emphasizing the need for high-efficiency propulsion to overcome Earth's gravity. Although similar concepts had been explored earlier, such as British mathematician William Moore's 1813 treatise A Treatise on the Motion of Rockets, which related rocket momentum to changing mass using Newtonian principles, Moore's analysis was more limited in scope and did not fully articulate the integrated form later attributed to Tsiolkovsky.[6] The full equation was also independently derived around the same period by others, including French aeronautical engineer Robert Esnault-Pelterie in the 1910s, American physicist Robert Goddard in 1912, and German rocket pioneer Hermann Oberth in 1920.[7] The equation bears Tsiolkovsky's name in recognition of his comprehensive application to space exploration, distinguishing it from prior partial derivations.[8] Beyond the equation itself, Tsiolkovsky's broader contributions to rocketry included visionary concepts like multi-stage rockets, which he elaborated in later publications to enable cumulative velocity gains for reaching orbital and interplanetary destinations.[9]Early Experiments

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, in his seminal 1903 work, illustrated the fundamental principle of rocket propulsion through a thought experiment involving a closed carriage. In this analogy, a person inside the carriage throws stones or masses backward with a certain velocity relative to the carriage, resulting in the carriage moving forward in the opposite direction due to the conservation of momentum in the isolated system.[10] This conceptual demonstration highlighted how a rocket could achieve motion in the vacuum of space without external forces, by expelling mass rearward.[9] Early practical experiments with liquid-fueled rockets were conducted by American physicist Robert Goddard in the 1920s. On March 16, 1926, Goddard successfully launched the world's first liquid-propellant rocket, using gasoline and liquid oxygen as fuels, which reached an altitude of approximately 12.5 meters and a speed of about 27 m/s (60 mph) over a 2.5-second flight.[11] Although Goddard did not explicitly reference Tsiolkovsky's equation in his publications, the performance of his rocket implicitly aligned with the equation's predictions for single-stage propulsion, demonstrating the logarithmic relationship between mass ratio and velocity change under ideal conditions. Subsequent tests by Goddard in the late 1920s and early 1930s, including rockets that achieved altitudes over 2 kilometers, further validated the core principles of variable mass propulsion.[12] Post-World War II efforts provided more robust empirical verifications through the analysis of German V-2 rockets. Launched from 1944 onward, the V-2 (or A-4) was a single-stage liquid-fueled ballistic missile using alcohol and liquid oxygen, capable of reaching altitudes up to 189 kilometers and speeds exceeding 1,600 meters per second. Postwar examinations by U.S. and Allied scientists, including telemetry data from over 60 V-2 launches at White Sands Missile Range between 1946 and 1950, confirmed that the rocket's burnout velocity closely matched predictions from the Tsiolkovsky equation when adjusted for initial mass, exhaust velocity (around 2,000 m/s), and final mass.[13] These tests marked the first large-scale demonstration of the equation's applicability to high-performance rocketry. However, early experiments also revealed key limitations of the ideal Tsiolkovsky equation. In Goddard's low-altitude flights, atmospheric drag significantly reduced achievable velocities compared to vacuum predictions, as the equation assumes no external forces. Similarly, V-2 data showed deviations during the initial ascent phase due to air resistance and gravity losses, which the basic formulation does not account for, necessitating trajectory corrections in real-world applications.[2]Mathematical Formulation

Statement of the Equation

The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, in its classical form, describes the change in velocity of a rocket as it expels propellant: where is the effective exhaust velocity, is the initial total mass of the rocket (including propellant), and is the final mass after propellant expulsion. This equation, first derived and published by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1903, predicts the maximum velocity change achievable in the absence of external forces, such as gravity or atmospheric drag, by converting the chemical or other energy of the propellant into kinetic energy through expulsion at high speed.[14] The equation employs the natural logarithm (base ) and is typically expressed in SI units, with and in meters per second (m/s) and masses in kilograms (kg), yielding in m/s. The logarithmic term highlights the exponential relationship between the mass ratio and the attainable velocity gain: even modest increases in the mass ratio can produce substantial , underscoring the efficiency challenges in rocket design where carrying excess propellant mass limits performance.[2]Definition of Terms

The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation relates the change in a rocket's velocity to its effective exhaust velocity and the ratio of initial to final mass; its variables carry specific physical meanings central to understanding rocket performance.[2] Delta-v (Δv) denotes the total change in velocity that a rocket can achieve through its propulsion system, assuming no external forces such as gravity or atmospheric drag act upon it.[1] This quantity serves as a fundamental measure of a propulsion system's capability, quantifying the impulse delivered to the vehicle and enabling mission planning by summing required Δv budgets for maneuvers like orbit insertion, trajectory corrections, or interplanetary transfers.[15] In practice, Δv is often decomposed into vector components corresponding to specific orbital or attitude adjustments, highlighting its role in vectorial navigation.[15] Mass fraction refers to the ratio of final mass to initial mass (m_f / m_0) or, equivalently, the propellant mass fraction as 1 - (m_f / m_0), which indicates the proportion of a rocket's total mass devoted to consumable propellant versus non-consumable components.[16] A higher propellant mass fraction signifies greater efficiency in propellant utilization, as it allows for larger velocity changes within the constraints of launch vehicle capacity, directly influencing the feasibility of achieving mission objectives.[17] Effective exhaust velocity (v_e) is the velocity of the exhaust gases relative to the rocket, representing the speed at which propellant is ejected to generate thrust, and it accounts for non-ideal effects such as nozzle expansion efficiency and pressure differences at the exit.[18] This parameter is equivalent to the product of specific impulse (I_sp) and standard gravitational acceleration (g_0 ≈ 9.81 m/s²), where I_sp measures the thrust produced per unit of propellant weight flow rate and serves as a key indicator of engine efficiency.[19] Higher v_e values enable greater Δv for a given mass ratio, underscoring its significance in optimizing propulsion systems for high-performance missions. The distinction between dry mass and wet mass is crucial for mass budgeting in rocket design: dry mass comprises the non-propellant components, including payload, structural elements, engines, and subsystems, while wet mass is the total initial mass encompassing the dry mass plus all propellant.[21] This separation highlights the impact of propellant loading on overall vehicle dynamics, as wet mass determines launch requirements whereas dry mass reflects the residual vehicle after burnout, directly affecting the achievable payload fraction.[22]Derivations

Standard Momentum-Based Derivation

The standard momentum-based derivation of the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation relies on the principle of conservation of momentum applied to a variable-mass system in an inertial reference frame, where no external forces act on the rocket. Consider a rocket with instantaneous mass moving at velocity along a straight line. In a small time interval, the rocket expels an infinitesimal mass of propellant rearward at a speed relative to the rocket itself; thus, the absolute velocity of the expelled mass in the inertial frame is . The rocket's mass becomes , and its velocity increases by an infinitesimal amount .[2] Conservation of momentum dictates that the total momentum before expulsion equals the total momentum after. The initial momentum is . The final momentum consists of the rocket's contribution, , plus the expelled mass's contribution, . Equating these gives: Expanding the right side yields , or after cancellation. Subtracting from both sides and neglecting the second-order infinitesimal term simplifies to: Rearranging provides the differential form: where the negative sign accounts for the decrease in mass ( for the rocket). To obtain the finite change in velocity , integrate the differential equation, assuming constant exhaust velocity . The limits are from initial mass (at ) to final mass (at ), with : The left side integrates to , while the right side gives . Thus, the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation is: This result shows that the achievable velocity change depends exponentially on the mass ratio.[14] The derivation assumes an absence of external forces (such as gravity or drag), constant exhaust velocity relative to the rocket, and one-dimensional motion, making it applicable to ideal conditions in deep space.[3]Alternative Classical Derivations

One alternative classical derivation of the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation employs the concept of total impulse delivered by the engine. The total impulse is defined as the time integral of the thrust force, which, assuming constant exhaust velocity , equals , where is the initial mass and is the final mass after fuel expulsion. To account for the varying mass during propulsion, the incremental change in velocity is related to the incremental impulse (with for mass loss) by , or . Integrating this from initial mass to final mass yields .[23] Another approach focuses on the acceleration of the rocket due to thrust. The thrust is given by , where is the mass flow rate. The instantaneous acceleration follows from Newton's second law as . The change in velocity is then . Integrating over the burn, assuming constant , again produces . This method emphasizes the time-dependent dynamics under Newtonian mechanics.[2] A third variant models fuel expulsion as a sequence of discrete pellets, providing insight into the continuum limit. Consider a rocket of initial mass expelling equal-mass pellets, each of mass (where is the fuel mass fraction), at constant relative speed rearward relative to the current rocket velocity. For the -th pellet, momentum conservation gives an incremental velocity change . Summing over all pellets yields the total . In the limit as , this discrete sum converges to the integral form . This derivation highlights the equation's origin in finite approximations approaching continuous propulsion.[24] These derivations—impulse-based, acceleration-based, and discrete pellet—are equivalent under the shared assumptions of constant exhaust velocity, no external forces, and Newtonian physics, all recovering the identical logarithmic expression for . They offer pedagogical variety compared to the baseline momentum conservation approach, reinforcing the equation's robustness across formulations.[3]Relativistic Derivation

The relativistic derivation of the rocket equation extends the classical formulation to account for velocities approaching the speed of light, incorporating special relativity's effects on momentum and velocity addition. The relativistic momentum of the rocket is given by , where is the instantaneous rest mass, is the velocity in the inertial lab frame, , and is the speed of light. This expression replaces the Newtonian to ensure conservation laws hold under Lorentz transformations. To derive the equation, consider the process in the rocket's instantaneous rest frame, where the analysis simplifies before transforming back to the lab frame. In this frame, a small mass (with for mass ejection) of exhaust is expelled rearward at constant proper speed relative to the rocket. The momentum imparted to the remaining rocket is (forward for the rocket), and since the frame is momentarily at rest, the velocity increment satisfies , or . However, relativistic velocity addition requires using rapidity , defined such that and , . The differential change in rapidity is in the rest frame, yielding . Integrating from initial rest (, mass ) to final state (, mass ) gives . Thus, the final velocity is .[25] An equivalent form for the special case of a photon rocket (u = c) expresses the mass ratio in terms of the final velocity: , where . This follows from the identity , substituting the integrated rapidity. This seminal result was first derived by Robert Esnault-Pelterie in 1928, and independently by Jakob Ackeret in 1946.[26] A key distinction from the classical equation is the emergence of hyperbolic functions, which cap the achievable below ; even as , asymptotically, preventing superluminal speeds. In the low-velocity limit (), the relativistic equation approximates the classical Tsiolkovsky form . The derivation assumes flat spacetime, no external forces such as gravity, and constant exhaust speed in the rocket's rest frame.[25]Applications and Limitations

Applicability and Assumptions

The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation applies under ideal conditions that simplify the dynamics of rocket propulsion to a closed system expelling mass. It assumes operation in a vacuum environment, where there are no atmospheric effects such as drag or pressure variations on the exhaust.[27] Additionally, the equation neglects external forces like gravity, treating the rocket as isolated from such influences during the velocity change calculation.[2] A key assumption is constant exhaust velocity , meaning the speed of the expelled propellant relative to the rocket remains uniform throughout the burn.[14] The model also presumes continuous, instantaneous mass expulsion without delays or inefficiencies in the propulsion process.[2] In real-world scenarios, these assumptions introduce significant limitations. Atmospheric drag during launch reduces the effective change in velocity by opposing the rocket's motion, necessitating additional propellant beyond what the equation predicts.[2] Real engines often exhibit variable due to factors like changing ambient pressure or propellant composition, deviating from the constant value assumed.[28] Gravity losses further complicate applicability, as the constant downward acceleration requires an extra budget—approximately where is gravitational acceleration and is burn time—to counteract it during ascent.[14] These effects make the ideal equation suitable only for preliminary estimates in vacuum or deep-space contexts, with corrections needed for planetary launches. The equation is not directly applicable to variable mass systems involving inflow, such as air-breathing engines like ramjets, where ambient air is ingested and mixed with fuel before expulsion, altering the momentum balance fundamentally.[28] It also fails to model scenarios with external thrust sources, like assist tugs or aerodynamic lift, as these introduce forces outside the isolated expulsion paradigm. For orbital mechanics applications, while the equation determines propellant needs for a required , it must be supplemented with trajectory calculations such as Hohmann transfers to account for orbital energy changes.[29] Furthermore, the model treats structural mass as invariant, ignoring variations from staging or payload deployment that occur in practice.[2]Multistage Rockets

In single-stage chemical rockets, practical mass ratios—typically limited to around 10 to 20 due to structural and material constraints—restrict the achievable change in velocity (Δv) to approximately 7–9 km/s (assuming v_e ≈ 3000 m/s), far short of the 9.4 km/s required for low Earth orbit.[30] Multistage rockets address this limitation by dividing the propulsion into sequential stages, each contributing independently to the total Δv according to the Tsiolkovsky equation applied per stage. After a stage's propellant is exhausted, its empty structure is jettisoned, reducing the overall mass for the remaining stages and allowing subsequent burns to accelerate a lighter payload more efficiently. The total Δv is the sum over all stages: where is the exhaust velocity of stage , is the initial mass of that stage (including its propellant and the mass of upper stages and payload), and is the final mass after burnout.[31] Konstantin Tsiolkovsky first proposed multi-stage rocket concepts in his 1929 book Space Rocket Trains, describing a "rocket train" of stacked stages fueled by liquid hydrogen and oxygen to cumulatively achieve Earth's escape velocity of about 11.2 km/s.[32] This approach was later realized in vehicles like the Saturn V, which employed three stages to deliver Apollo payloads to the Moon, providing a total Δv exceeding 11 km/s. Optimizing multistage designs involves minimizing the total initial mass for a specified payload and mission Δv, often by balancing propellant fractions across stages while accounting for the structural factor , defined as the ratio of a stage's dry (structural) mass to its total initial mass (). Lower values, typically 0.05–0.15 for advanced stages, enhance efficiency by reducing inert mass carried throughout the flight.[16] Although additional stages can exponentially improve Δv by iteratively discarding dead weight, they increase system complexity through more interfaces, separation mechanisms, and potential failure points, raising costs and reliability challenges while offering diminishing returns beyond three or four stages for most chemical propulsion missions.[30] The rocket equation () demonstrates that achieving greater velocity change requires exponentially increasing initial mass for more fuel. Traditional staging mitigates this by discarding empty stages to reduce final mass, but orbital refueling avoids it by launching fuel separately in multiple small, reusable missions, preventing the need for a single impractically massive rocket and lowering marginal costs.[33][34][35]Illustrative Examples

To illustrate the application of the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, consider a hypothetical single-stage rocket with an initial total mass kg, a final mass after propellant expulsion kg (yielding a mass ratio of 10), and exhaust velocity m/s. The change in velocity is given by m/s, or approximately 6.9 km/s.[2] This demonstrates how a modest mass ratio can produce significant velocity gains, fundamental to escaping Earth's gravity. In a real-world context, the SpaceX Falcon 9 first stage exemplifies practical implementation during reusable missions. The stage has an initial mass of approximately 433 metric tons (including propellant load of about 396 metric tons) and a dry mass of around 26 metric tons, but for reusability, not all propellant is expended during ascent to maximize payload delivery while reserving mass for landing—resulting in an effective mass ratio of roughly 4 and a averaging 2950 m/s (from Merlin 1D engines with Isp near 300 s). This yields an ascent contribution of approximately 3 km/s, enabling the stage to reach downrange separation velocities before boost-back and landing maneuvers.[36] For multistage configurations, the total is the sum of individual stage contributions. Consider a two-stage rocket where each stage has a mass ratio of 10 and m/s. Each stage provides km/s, for a total of approximately 13.8 km/s—sufficient for interplanetary trajectories when combined with orbital mechanics. This additive approach highlights why staging discards inert mass efficiently.[2] The equation's exponential nature underscores sensitivity to mass fractions. For instance, increasing the propellant fraction from 80% (mass ratio 5, km/s at m/s) to 90% (mass ratio 10, km/s) more than doubles the velocity gain, illustrating how small structural improvements yield outsized performance benefits.[2] As of 2025, reusable systems like SpaceX's Starship optimize mass fractions for Mars missions, targeting propellant loads exceeding 1200 metric tons per stage with dry masses under 5% of wet mass through advanced materials and in-orbit refueling. This achieves effective mass ratios over 20 per stage, enabling budgets for Earth-to-Mars transit (around 6 km/s post-orbit) while supporting return trips via on-site propellant production. Orbital refueling in this context circumvents the rocket equation's exponential mass penalty by assembling fuel in orbit via multiple launches, offering advantages over additional staging by reducing the need for more complex vehicle structures and lowering overall mission costs.[37][38][34][35]References

- https://science.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/learn/basics-of-space-flight/chapter3-2/

![{\displaystyle ~\Delta v=v_{f}-v_{0}=-v_{\text{e}}\left[\ln m_{f}-\ln m_{0}\right]=~v_{\text{e}}\ln \left({\frac {m_{0}}{m_{f}}}\right).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e6b3f9376e3f80de022939656d53c9fdb0f5a881)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {m_{0}}{m_{1}}}=\left[{\frac {1+{\frac {\Delta v}{c}}}{1-{\frac {\Delta v}{c}}}}\right]^{\frac {c}{2v_{\text{e}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/506b68f3ef6f9d1d236a2f4ab7bfbf995189b937)

![{\textstyle R^{\frac {2v_{\text{e}}}{c}}=\exp \left[{\frac {2v_{\text{e}}}{c}}\ln R\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/efed86ee6ab335e3c73886168248dbc1443e0b40)