Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Celestial navigation

View on WikipediaThis article's lead section may be too long. (February 2024) |

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space or on the surface of the Earth without relying solely on estimated positional calculations, commonly known as dead reckoning. Celestial navigation is performed without using satellite navigation or other similar modern electronic or digital positioning means.

Celestial navigation uses "sights," or timed angular measurements, taken typically between a celestial body (e.g., the Sun, the Moon, a planet, or a star) and the visible horizon. Celestial navigation can also take advantage of measurements between celestial bodies without reference to the Earth's horizon, such as when the Moon and other selected bodies are used in the practice called "lunars" or the lunar distance method, used for determining precise time when time is unknown.

Celestial navigation by taking sights of the Sun and the horizon whilst on the surface of the Earth is commonly used, providing various methods of determining position, one of which is the popular and simple method called "noon sight navigation"—being a single observation of the exact altitude of the Sun and the exact time of that altitude (known as "local noon")—the highest point of the Sun above the horizon from the position of the observer in any single day. This angular observation, combined with knowing its simultaneous precise time, referred to as the time at the prime meridian, directly renders a latitude and longitude fix at the time and place of the observation by simple mathematical reduction. The Moon, a planet, Polaris, or one of the 57 other navigational stars whose coordinates are tabulated in any of the published nautical or air almanacs can also accomplish this same goal.

Celestial navigation accomplishes its purpose by using angular measurements (sights) between celestial bodies and the visible horizon to locate one's position on the Earth, whether on land, in the air, or at sea. In addition, observations between stars and other celestial bodies accomplished the same results while in space, – used in the Apollo space program and is still used on many contemporary satellites. Equally, celestial navigation may be used while on other planetary bodies to determine position on their surface, using their local horizon and suitable celestial bodies with matching reduction tables and knowledge of local time.

For navigation by celestial means, when on the surface of the Earth at any given instant in time, a celestial body is located directly over a single point on the Earth's surface. The latitude and longitude of that point are known as the celestial body's geographic position (GP), the location of which can be determined from tables in the nautical or air almanac for that year. The measured angle between the celestial body and the visible horizon is directly related to the distance between the celestial body's GP and the observer's position. After some computations, referred to as "sight reduction," this measurement is used to plot a line of position (LOP) on a navigational chart or plotting worksheet, with the observer's position being somewhere on that line. The LOP is actually a short segment of a very large circle on Earth that surrounds the GP of the observed celestial body. (An observer located anywhere on the circumference of this circle on Earth, measuring the angle of the same celestial body above the horizon at that instant of time, would observe that body to be at the same angle above the horizon.) Sights on two celestial bodies give two such lines on the chart, intersecting at the observer's position (actually, the two circles would result in two points of intersection arising from sights on two stars described above, but one can be discarded since it will be far from the estimated position—see the figure at the example below). Most navigators will use sights of three to five stars, if available, since that will result in only one common intersection and minimize the chance of error. That premise is the basis for the most commonly used method of celestial navigation, referred to as the "altitude-intercept method." At least three points must be plotted. The plot intersection will usually provide a triangle where the exact position is inside of it. The accuracy of the sights is indicated by the size of the triangle.

Joshua Slocum used both noon sight and star sight navigation to determine his current position during his voyage, the first recorded single-handed circumnavigation of the world. In addition, he used the lunar distance method (or "lunars") to determine and maintain known time at Greenwich (the prime meridian), thereby keeping his "tin clock" reasonably accurate and therefore his position fixes accurate.

Celestial navigation can only determine longitude when the time at the prime meridian is accurately known. The more accurately time at the prime meridian (0° longitude) is known, the more accurate the fix; – indeed, every four seconds of time source (commonly a chronometer or, in aircraft, an accurate "hack watch") error can lead to a positional error of one nautical mile. When time is unknown or not trusted, the lunar distance method can be used as a method of determining time at the prime meridian. A functioning timepiece with a second hand or digit, an almanac with lunar corrections, and a sextant are used. With no knowledge of time at all, a lunar calculation (given an observable Moon of respectable altitude) can provide time accurate to within a second or two with about 15 to 30 minutes of observations and mathematical reduction from the almanac tables. After practice, an observer can regularly derive and prove time using this method to within about one second, or one nautical mile, of navigational error due to errors ascribed to the time source.

Example

[edit]

An example illustrating the concept behind the intercept method for determining position is shown to the right. (Two other common methods for determining one's position using celestial navigation are longitude by chronometer and ex-meridian methods.) In the adjacent image, the two circles on the map represent lines of position for the Sun and Moon at 12:00 GMT on October 29, 2005. At this time, a navigator on a ship at sea measured the Moon to be 56° above the horizon using a sextant. Ten minutes later, the Sun was observed to be 40° above the horizon. Lines of position were then calculated and plotted for each of these observations. Since both the Sun and Moon were observed at their respective angles from the same location, the navigator would have to be located at one of the two locations where the circles cross.

In this case, the navigator is either located on the Atlantic Ocean, about 350 nautical miles (650 km) west of Madeira, or in South America, about 90 nautical miles (170 km) southwest of Asunción, Paraguay. In most cases, determining which of the two intersections is the correct one is obvious to the observer because they are often thousands of miles apart. As it is unlikely that the ship is sailing across South America, the position in the Atlantic is the correct one. Note that the lines of position in the figure are distorted because of the map's projection; they would be circular if plotted on a globe.

An observer at the Gran Chaco point would see the Moon at the left of the Sun, and an observer at the Madeira point would see the Moon at the right of the Sun.

Angular measurement

[edit]

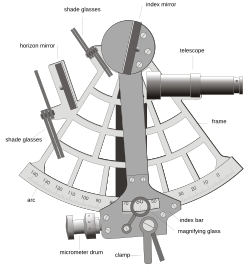

Accurate angle measurement has evolved over the years. One simple method is to hold the hand above the horizon with one's arm stretched out. The angular width of the little finger is just over 1.5 degrees at extended arm's length and can be used to estimate the elevation of the Sun from the horizon plane and therefore estimate the time until sunset. The need for more accurate measurements led to the development of a number of increasingly accurate instruments, including the kamal, astrolabe, octant, and sextant. The sextant and octant are most accurate because they measure angles from the horizon, eliminating errors caused by the placement of an instrument's pointers, and because their dual-mirror system cancels relative motions of the instrument, showing a steady view of the object and horizon.

Navigators measure distance on the Earth in degrees, arcminutes, and arcseconds. A nautical mile is defined as 1,852 meters but is also (not accidentally) one arc minute of angle along a meridian on the Earth. Sextants can be read accurately to within 0.1 arcminutes, so the observer's position can be determined within (theoretically) 0.1 nautical miles (185.2 meters, or about 203 yards). Most ocean navigators, measuring from a moving platform under fair conditions, can achieve a practical accuracy of approximately 1.5 nautical miles (2.8 km), enough to navigate safely when out of sight of land or other hazards.[1]

Practical navigation

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2011) |

Practical celestial navigation usually requires a marine chronometer to measure time, a sextant to measure the angles, an almanac[2] giving schedules of the coordinates of celestial objects, a set of sight reduction tables to help perform the height and azimuth computations, and a chart of the region.[3] With sight reduction tables, the only calculations required are addition and subtraction.[4] Small handheld computers, laptops and even scientific calculators enable modern navigators to "reduce" sextant sights in minutes, by automating all the calculation and/or data lookup steps.[5] Most people can master simpler celestial navigation procedures after a day or two of instruction and practice, even using manual calculation methods.

Modern practical navigators usually use celestial navigation in combination with satellite navigation to correct a dead reckoning track, that is, a course estimated from a vessel's position, course, and speed. Using multiple methods helps the navigator detect errors and simplifies procedures. When used this way, a navigator, from time to time, measures the Sun's altitude with a sextant, then compares that with a precalculated altitude based on the exact time and estimated position of the observation. On the chart, the straight edge of a plotter can mark each position line. If the position line indicates a location more than a few miles from the estimated position, more observations can be taken to restart the dead-reckoning track.[6]

In the event of equipment or electrical failure, taking Sun lines a few times a day and advancing them by dead reckoning allows a vessel to get a crude running fix sufficient to return to port. One can also use the Moon, a planet, Polaris, or one of 57 other navigational stars to track celestial positioning.

Latitude

[edit]

Latitude was measured in the past either by measuring the altitude of the Sun at noon (the "noon sight") or by measuring the altitudes of any other celestial body when crossing the meridian (reaching its maximum altitude when due north or south), and frequently by measuring the altitude of Polaris, the north star (assuming it is sufficiently visible above the horizon, which it is not in the Southern Hemisphere). Polaris always stays within 1 degree of the celestial north pole. If a navigator measures the angle to Polaris and finds it to be 10 degrees from the horizon, then he is about 10 degrees north of the equator. This approximate latitude is then corrected using simple tables or almanac corrections to determine a latitude that is theoretically accurate to within a fraction of a mile. Angles are measured from the horizon because locating the point directly overhead, the zenith, is not normally possible. When haze obscures the horizon, navigators use artificial horizons, which are horizontal mirrors or pans of reflective fluid, especially mercury. In the latter case, the angle between the reflected image in the mirror and the actual image of the object in the sky is exactly twice the required altitude.

Longitude

[edit]

If the angle to Polaris can be accurately measured, a similar measurement of a star near the eastern or western horizons would provide the longitude. The problem is that the Earth turns 15 degrees per hour, making such measurements dependent on time. A measure a few minutes before or after the same measure the day before creates serious navigation errors. Before good chronometers were available, longitude measurements were based on the transit of the moon or the positions of the moons of Jupiter. For the most part, these were too difficult to be used by anyone except professional astronomers. The invention of the modern chronometer by John Harrison in 1761 vastly simplified longitudinal calculation.

The longitude problem took centuries to solve and was dependent on the construction of a non-pendulum clock (as pendulum clocks cannot function accurately on a tilting ship, or indeed a moving vehicle of any kind). Two useful methods evolved during the 18th century and are still practiced today: lunar distance, which does not involve the use of a chronometer, and the use of an accurate timepiece or chronometer.

Presently, layperson calculations of longitude can be made by noting the exact local time (leaving out any reference for daylight saving time) when the Sun is at its highest point in Earth's sky. The calculation of noon can be made more easily and accurately with a small, exactly vertical rod driven into level ground—take the time reading when the shadow is pointing due north (in the northern hemisphere). Then take your local time reading and subtract it from GMT (Greenwich Mean Time), or the time in London, England. For example, a noon reading (12:00) near central Canada or the US would occur at approximately 6 p.m. (18:00) in London. The 6-hour difference is one quarter of a 24-hour day, or 90 degrees of a 360-degree circle (the Earth). The calculation can also be made by taking the number of hours (use decimals for fractions of an hour) multiplied by 15, the number of degrees in one hour. Either way, it can be demonstrated that much of central North America is at or near 90 degrees west longitude. Eastern longitudes can be determined by adding the local time to GMT, with similar calculations.

Lunar distance

[edit]An older but still useful and practical method of determining accurate time at sea before the advent of precise timekeeping and satellite-based time systems is called "lunar distances," or "lunars," which was used extensively for a short period and refined for daily use on board ships in the 18th century. Use declined through the middle of the 19th century as better and better timepieces (chronometers) became available to the average vessel at sea. Although most recently only used by sextant hobbyists and historians, it is now becoming more common in celestial navigation courses to reduce total dependence on GNSS systems as potentially the only accurate time source aboard a vessel. Designed for use when an accurate timepiece is not available or timepiece accuracy is suspect during a long sea voyage, the navigator precisely measures the angle between the Moon and the Sun or between the Moon and one of several stars near the ecliptic. The observed angle must be corrected for the effects of refraction and parallax, like any celestial sight. To make this correction, the navigator measures the altitudes of the Moon and Sun (or another star) at about the same time as the lunar distance angle. Only rough values for the altitudes are required. A calculation with suitable published tables (or longhand with logarithms and graphical tables) requires about 10 to 15 minutes' work to convert the observed angle(s) to a geocentric lunar distance. The navigator then compares the corrected angle against those listed in the appropriate almanac pages for every three hours of Greenwich time, using interpolation tables to derive intermediate values. The result is a difference in time between the time source (of unknown time) used for the observations and the actual prime meridian time (that of the "Zero Meridian" at Greenwich, also known as UTC or GMT). Knowing UTC/GMT, a further set of sights can be taken and reduced by the navigator to calculate their exact position on the Earth as a local latitude and longitude.

Use of time

[edit]The considerably more popular method was (and still is) to use an accurate timepiece to directly measure the time of a sextant sight. The need for accurate navigation led to the development of progressively more accurate chronometers in the 18th century (see John Harrison). Today, time is measured with a chronometer, a quartz watch, a shortwave radio time signal broadcast from an atomic clock, or the time displayed on a satellite time signal receiver.[7] A quartz wristwatch normally keeps time within a half-second per day. If it is worn constantly, keeping it near body heat, its rate of drift can be measured with the radio, and by compensating for this drift, a navigator can keep time to better than a second per month. When time at the prime meridian (or another starting point) is accurately known, celestial navigation can determine longitude, and the more accurately latitude and time are known, the more accurate the longitude determination. The angular speed of the Earth is latitude-dependent. At the poles, or latitude 90°, the rotation velocity of the Earth reaches zero. At 45° latitude, one second of time is equivalent in longitude to 1,077.8 ft (328.51 m), or one-tenth of a second means 107.8 ft (32.86 m)[8] At the slightly bulged-out equator, or latitude 0°, the rotation velocity of Earth or its equivalent in longitude reaches its maximum at 465.10 m/s (1,525.9 ft/s).[9]

Traditionally, a navigator checked their chronometer(s) with their sextant at a geographic marker surveyed by a professional astronomer. This is now a rare skill, and most harbormasters cannot locate their harbor's marker. Ships often carried more than one chronometer. Chronometers were kept on gimbals in a dry room near the center of the ship. They were used to set a hack watch for the actual sight, so that no chronometers were ever exposed to the wind and salt water on deck. Winding and comparing the chronometers was a crucial duty of the navigator. Even today, it is still logged daily in the ship's deck log and reported to the captain before eight bells on the forenoon watch (shipboard noon). Navigators also set the ship's clocks and calendar. Two chronometers provided dual modular redundancy, allowing a backup if one ceases to work but not allowing any error correction if the two displayed a different time, since in case of contradiction between the two chronometers, it would be impossible to know which one was wrong (the error detection obtained would be the same as having only one chronometer and checking it periodically: every day at noon against dead reckoning). Three chronometers provided triple modular redundancy, allowing error correction if one of the three was wrong, so the pilot would take the average of the two with closer readings (average precision vote). There is an old adage to this effect, stating: "Never go to sea with two chronometers; take one or three."[10] Vessels engaged in survey work generally carried many more than three chronometers – for example, HMS Beagle carried 22 chronometers.[11]

Modern celestial navigation

[edit]The celestial line of position concept was discovered in 1837 by Thomas Hubbard Sumner when, after one observation, he computed and plotted his longitude at more than one trial latitude in his vicinity and noticed that the positions lay along a line. Using this method with two bodies, navigators were finally able to cross two position lines and obtain their position, in effect determining both latitude and longitude. Later in the 19th century came the development of the modern (Marcq St. Hilaire) intercept method; with this method, the body height and azimuth are calculated for a convenient trial position and compared with the observed height. The difference in arcminutes is the nautical mile "intercept" distance that the position line needs to be shifted toward or away from the direction of the body's subpoint. (The intercept method uses the concept illustrated in the example in the "How it works" section above.) Two other methods of reducing sights are the longitude by chronometer and the ex-meridian method.

While celestial navigation is becoming increasingly redundant with the advent of inexpensive and highly accurate satellite navigation receivers (GNSS), it was used extensively in aviation until the 1960s and marine navigation until quite recently. However, since a prudent mariner never relies on any sole means of fixing their position, many national maritime authorities still require deck officers to show knowledge of celestial navigation in examinations, primarily as a backup for electronic or satellite navigation. One of the most common current uses of celestial navigation aboard large merchant vessels is for compass calibration and error checking at sea when no terrestrial references are available.

In 1980, French Navy regulations still required an independently operated timepiece on board so that, in combination with a sextant, a ship's position could be determined by celestial navigation.[12]

The U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy continued instructing military aviators on celestial navigation use until 1997, because:

- celestial navigation can be used independently of ground aids.

- celestial navigation has global coverage.

- celestial navigation cannot be jammed (although it can be obscured by clouds).

- celestial navigation does not give off any signals that could be detected by an enemy.[13]

The United States Naval Academy (USNA) announced that it was discontinuing its course on celestial navigation (considered to be one of its most demanding non-engineering courses) from the formal curriculum in the spring of 1998.[14] In October 2015, citing concerns about the reliability of GNSS systems in the face of potential hostile hacking, the USNA reinstated instruction in celestial navigation in the 2015 to 2016 academic year.[15][16]

At another federal service academy, the US Merchant Marine Academy, there was no break in instruction in celestial navigation as it is required to pass the US Coast Guard License Exam to enter the Merchant Marine. It is also taught at Harvard, most recently as Astronomy 2.[17]

Celestial navigation continues to be used by private yachtsmen, and particularly by long-distance cruising yachts around the world. For small cruising boat crews, celestial navigation is generally considered an essential skill when venturing beyond visual range of land. Although satellite navigation technology is reliable, offshore yachtsmen use celestial navigation as either a primary navigational tool or as a backup.

Celestial navigation was used in commercial aviation up until the early part of the jet age; early Boeing 747s had a "sextant port" in the roof of the cockpit.[18] It was only phased out in the 1960s with the advent of inertial navigation and Doppler navigation systems, and today's satellite-based systems which can locate the aircraft's position accurate to a 3-meter sphere with several updates per second.

A variation on terrestrial celestial navigation was used to help orient the Apollo spacecraft en route to and from the Moon. To this day, space missions such as the Mars Exploration Rover use star trackers to determine the attitude of the spacecraft.

As early as the mid-1960s, advanced electronic and computer systems had evolved enabling navigators to obtain automated celestial sight fixes. These systems were used aboard both ships and US Air Force aircraft, and were highly accurate, able to lock onto up to 11 stars (even in daytime) and resolve the craft's position to less than 300 feet (91 m). The SR-71 high-speed reconnaissance aircraft was one example of an aircraft that used a combination of automated celestial and inertial navigation. These rare systems were expensive, however, and the few that remain in use today are regarded as backups to more reliable satellite positioning systems.

Intercontinental ballistic missiles use celestial navigation to check and correct their course (initially set using internal gyroscopes) while flying outside the Earth's atmosphere. The immunity to jamming signals is the main driver behind this seemingly archaic technique.

X-ray pulsar-based navigation and timing (XNAV) is an experimental navigation technique for space whereby the periodic X-ray signals emitted from pulsars are used to determine the location of a vehicle, such as a spacecraft in deep space. A vehicle using XNAV would compare received X-ray signals with a database of known pulsar frequencies and locations. Similar to GNSS, this comparison would allow the vehicle to triangulate its position accurately (±5 km). The advantage of using X-ray signals over radio waves is that X-ray telescopes can be made smaller and lighter.[19][20][21] On 9 November 2016 the Chinese Academy of Sciences launched an experimental pulsar navigation satellite called XPNAV 1.[22][23] SEXTANT (Station Explorer for X-ray Timing and Navigation Technology) is a NASA-funded project developed at the Goddard Space Flight Center that is testing XNAV on-orbit aboard the International Space Station in connection with the NICER project, launched on 3 June 2017 on the SpaceX CRS-11 ISS resupply mission.[24]

Training

[edit]Celestial navigation training equipment for aircraft crews combine a simple flight simulator with a planetarium.

An early example is the Link Celestial Navigation Trainer, used in the Second World War.[25][26] Housed in a 45-foot (14 m) high building, it featured a cockpit accommodating a whole bomber crew (pilot, navigator, and bombardier). The cockpit offered a full array of instruments, which the pilot used to fly the simulated airplane. Fixed to a dome above the cockpit was an arrangement of lights, some collimated, simulating constellations, from which the navigator determined the plane's position. The dome's movement simulated the changing positions of the stars with the passage of time and the movement of the plane around the Earth. The navigator also received simulated radio signals from various positions on the ground. Below the cockpit moved "terrain plates"—large, movable aerial photographs of the land below—which gave the crew the impression of flight and enabled the bomber to practice lining up bombing targets. A team of operators sat at a control booth on the ground below the machine, from which they could simulate weather conditions such as wind or clouds. This team also tracked the airplane's position by moving a "crab" (a marker) on a paper map.

The Link Celestial Navigation Trainer was developed in response to a request made by the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1939. The RAF ordered 60 of these machines, and the first one was built in 1941. The RAF used only a few of these, leasing the rest back to the US, where eventually hundreds were in use.

See also

[edit]- Air navigation

- Aircraft periscope

- Astrodome (aeronautics)

- Astronautics

- Bowditch's American Practical Navigator

- Celestial pole

- Circle of equal altitude

- Ephemeris

- Geodetic astronomy

- GNSS Satellite navigation

- History of longitude

- List of proper names of stars

- List of selected stars for navigation on

- Polar alignment

- Polynesian navigation

- Radio navigation

- Spherical geometry

- Star clock

References

[edit]- ^ How Accurate Is Celestial Navigation Compared To GPS?

- ^ The free online Nautical Almanac in PDF format.

- ^ "07.03.09: The Mathematical Dynamics of Celestial Navigation and Astronavigation". teachersinstitute.yale.edu. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ Navigator, Ocean (2003-01-01). "Sight reduction methods compared - Ocean Navigator". Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ THE AMERICAN PRACTICAL NAVIGATORAN EPITOME OF NAVIGATION, p. 270.

- ^ "Marine navigation courses: Lines of position, LOPs". www.sailingissues.com. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ Mehaffey, Joe. "How accurate is the TIME DISPLAY on my GPS?". gpsinformation.net. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Errors in Longitude, Latitude and Azimuth Determinations — I by F. A. McDiarmid, The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 1914.

- ^ Arthur N. Cox, ed. (2000). Allen's Astrophysical Quantities (4th ed.). New York: AIP Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-387-98746-0. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Brooks, Frederick J. (1995) [1975]. The Mythical Man-Month. Addison-Wesley. p. 64. ISBN 0-201-83595-9.

- ^ R. Fitzroy. "Volume II: Proceedings of the Second Expedition". p. 18.

- ^ The marine chronometer in the age of electricity by David Read, September 2015

- ^ U.S. Air Force Pamphlet (AFPAM) 11-216, Chapters 8–13

- ^ Navy Cadets Won't Discard Their Sextants Archived 2009-02-13 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times By DAVID W. CHEN Published: May 29, 1998

- ^ Seeing stars, again: Naval Academy reinstates celestial navigation Archived 2015-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Capital Gazette by Tim Prudente Published: 12 October 2015

- ^ Peterson, Andrea (17 February 2016). "Why Naval Academy students are learning to sail by the stars for the first time in a decade". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016.

- ^ – Astronomy 2 Celestial Navigation by Philip Sadler Archived 2015-11-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Clark, Pilita (17 April 2015). "The future of flying". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Commissariat, Tushna (4 June 2014). "Pulsars map the way for space missions". Physics World. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017.

- ^ "An Interplanetary GPS Using Pulsar Signals". MIT Technology Review. 23 May 2013. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Becker, Werner; Bernhardt, Mike G.; Jessner, Axel (2013-05-21). "Autonomous Spacecraft Navigation With Pulsars". Acta Futura. 7 (7): 11–28. arXiv:1305.4842. Bibcode:2013AcFut...7...11B. doi:10.2420/AF07.2013.11. S2CID 118570784.

- ^ Krebs, Gunter. "XPNAV 1". Gunter's Space Page. Archived from the original on 2016-11-01. Retrieved 2016-11-01.

- ^ "Chinese Long March 11 launches first Pulsar Navigation Satellite into Orbit". Spaceflight101.com. 10 November 2016. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017.

- ^ "NICER Manifested on SpaceX-11 ISS Resupply Flight". NICER News. NASA. December 1, 2015. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

Previously scheduled for a December 2016 launch on SpaceX-12, NICER will now fly to the International Space Station with two other payloads on SpaceX Commercial Resupply Services (CRS)-11, in the Dragon vehicle's unpressurized Trunk.

- ^ "World War II". A Brief History of Aircraft Flight Simulation. Archived from the original on December 9, 2004. Retrieved January 27, 2005.

- ^ "Corporal Tomisita "Tommye" Flemming-Kelly-U.S.M.C.-Celestial Navigation Trainer −1943/45". World War II Memories. Archived from the original on 2005-01-19. Retrieved January 27, 2005.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Celestial navigation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Celestial navigation at Wikimedia Commons

- Celestial Navigation Net

- Table of the 57 navigational stars with apparent magnitudes and celestial coordinates

- Inua Complete nautical Almanac and more

- Calculating Lunar Distances

- Backbearing.com Almanac, Sight Reduction Tables and more.

- Celestial Navigation in Petan.net

- Air Facts

- THE V-FORCE

- Air Navigation Sextants

- Sextant in a Douglas DC-8