Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Apollo program

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Program overview | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Organization | NASA |

| Purpose | Crewed lunar landing |

| Status | Completed |

| Program history | |

| Cost |

|

| Duration | 1961–1972 |

| First flight |

|

| First crewed flight |

|

| Last flight |

|

| Successes | 32 |

| Failures | 2 (Apollo 1 and 13) |

| Partial failures | 1 (Apollo 6) |

| Launch sites | |

| Vehicle information | |

| Crewed vehicles | |

| Launch vehicles | |

| Part of a series on the |

| United States space program |

|---|

|

The Apollo program, also known as Project Apollo, was the United States human spaceflight program led by NASA, which landed the first humans on the Moon in 1969. Apollo was conceived during Project Mercury and executed after Project Gemini. It was conceived in 1960 as a three-person spacecraft during the presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower. Apollo was later dedicated to President John F. Kennedy's national goal for the 1960s of "landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth" in an address to the U.S. Congress on May 25, 1961.

Kennedy's goal was accomplished on the Apollo 11 mission, when astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed their Apollo Lunar Module (LM) on July 20, 1969, and walked on the lunar surface, while Michael Collins remained in lunar orbit in the command and service module (CSM), and all three landed safely on Earth in the Pacific Ocean on July 24. Five subsequent Apollo missions also landed astronauts on the Moon, the last, Apollo 17, in December 1972. In these six spaceflights, twelve people walked on the Moon.

Apollo ran from 1961 to 1972, with the first crewed flight in 1968. It encountered a major setback in 1967 when the Apollo 1 cabin fire killed the entire crew during a prelaunch test. After the first Moon landing, sufficient flight hardware remained for nine follow-on landings with a plan for extended lunar geological and astrophysical exploration. Budget cuts forced the cancellation of three of these. Five of the remaining six missions achieved landings; but the Apollo 13 landing had to be aborted after an oxygen tank exploded en route to the Moon, crippling the CSM. The crew barely managed a safe return to Earth by using the Lunar Module as a "lifeboat" on the return journey. Apollo used the Saturn family of rockets as launch vehicles, which were also used for an Apollo Applications Program, which consisted of Skylab, a space station that supported three crewed missions in 1973–1974, and the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project, a joint United States-Soviet Union low Earth orbit mission in 1975.

Apollo set several major human spaceflight milestones. It stands alone in sending crewed missions beyond low Earth orbit. Apollo 8 was the first crewed spacecraft to orbit another celestial body, and Apollo 11 was the first crewed spacecraft to land humans on one.

Overall, the Apollo program returned 842 pounds (382 kg) of lunar rocks and soil to Earth, greatly contributing to the understanding of the Moon's composition and geological history. The program laid the foundation for NASA's subsequent human spaceflight capability and funded construction of its Johnson Space Center and Kennedy Space Center. Apollo also spurred advances in many areas of technology incidental to rocketry and human spaceflight, including avionics, telecommunications, and computers.

Name

[edit]The program was named after the Greek god Apollo by NASA manager Abe Silverstein, who later said, "I was naming the spacecraft like I'd name my baby."[2] Silverstein chose the name at home one evening, early in 1960, because he felt "Apollo riding his chariot across the Sun was appropriate to the grand scale of the proposed program".[3]

The context of this was that the program focused at its beginning mainly on developing an advanced crewed spacecraft, the Apollo command and service module, succeeding the Mercury program. A lunar landing became the focus of the program only in 1961.[4] Thereafter Project Gemini instead followed the Mercury program to test and study advanced crewed spaceflight technology.

Background

[edit]Origin and spacecraft feasibility studies

[edit]The Apollo program was conceived during the Eisenhower administration in early 1960, as a follow-up to Project Mercury. While the Mercury capsule could support only one astronaut on a limited Earth orbital mission, Apollo would carry three. Possible missions included ferrying crews to a space station, circumlunar flights, and eventual crewed lunar landings.

In July 1960, NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh L. Dryden announced the Apollo program to industry representatives at a series of Space Task Group conferences. Preliminary specifications were laid out for a spacecraft with a mission module cabin separate from the command module (piloting and reentry cabin), and a propulsion and equipment module. On August 30, a feasibility study competition was announced, and on October 25, three study contracts were awarded to General Dynamics/Convair, General Electric, and the Glenn L. Martin Company. Meanwhile, NASA performed its own in-house spacecraft design studies led by Maxime Faget, to serve as a gauge to judge and monitor the three industry designs.[5]

Political pressure builds

[edit]In November 1960, John F. Kennedy was elected president after a campaign that promised American superiority over the Soviet Union in the fields of space exploration and missile defense. Up to the election of 1960, Kennedy had been speaking out against the "missile gap" that he and many other senators said had developed between the Soviet Union and the United States due to the inaction of President Eisenhower.[6] Beyond military power, Kennedy used aerospace technology as a symbol of national prestige, pledging to make the US not "first but, first and, first if, but first period".[7] Despite Kennedy's rhetoric, he did not immediately come to a decision on the status of the Apollo program once he became president. He knew little about the technical details of the space program, and was put off by the massive financial commitment required by a crewed Moon landing.[8] When Kennedy's newly appointed NASA Administrator James E. Webb requested a 30 percent budget increase for his agency, Kennedy supported an acceleration of NASA's large booster program but deferred a decision on the broader issue.[9]

On April 12, 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person to fly in space, reinforcing American fears about being left behind in a technological competition with the Soviet Union. At a meeting of the US House Committee on Science and Astronautics one day after Gagarin's flight, many congressmen pledged their support for a crash program aimed at ensuring that America would catch up.[10] Kennedy was circumspect in his response to the news, refusing to make a commitment on America's response to the Soviets.[11]

On April 20, Kennedy sent a memo to Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, asking Johnson to look into the status of America's space program, and into programs that could offer NASA the opportunity to catch up.[12][13] Johnson responded approximately one week later, concluding that "we are neither making maximum effort nor achieving results necessary if this country is to reach a position of leadership."[14][15] His memo concluded that a crewed Moon landing was far enough in the future that it was likely the United States would achieve it first.[14]

On May 25, 1961, twenty days after the first American crewed spaceflight Freedom 7, Kennedy proposed the crewed Moon landing in a Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs:

Now it is time to take longer strides—time for a great new American enterprise—time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on Earth.

... I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important in the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.[16][a]

NASA expansion

[edit]At the time of Kennedy's proposal, only one American had flown in space—less than a month earlier—and NASA had not yet sent an astronaut into orbit. Even some NASA employees doubted whether Kennedy's ambitious goal could be met.[17] By 1963, Kennedy even came close to agreeing to a joint US-USSR Moon mission, to eliminate duplication of effort.[18]

With the clear goal of a crewed landing replacing the more nebulous goals of space stations and circumlunar flights, NASA decided that, in order to make progress quickly, it would discard the feasibility study designs of Convair, GE, and Martin, and proceed with Faget's command and service module design. The mission module was determined to be useful only as an extra room, and therefore unnecessary.[19] They used Faget's design as the specification for another competition for spacecraft procurement bids in October 1961. On November 28, 1961, it was announced that North American Aviation had won the contract, although its bid was not rated as good as the Martin proposal. Webb, Dryden and Robert Seamans chose it in preference due to North American's longer association with NASA and its predecessor.[20]

Landing humans on the Moon by the end of 1969 required the most sudden burst of technological creativity, and the largest commitment of resources ($25 billion; $187 billion in 2024 US dollars)[21] ever made by any nation in peacetime. At its peak, the Apollo program employed 400,000 people and required the support of over 20,000 industrial firms and universities.[22]

On July 1, 1960, NASA established the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Alabama. MSFC designed the heavy lift-class Saturn launch vehicles, which would be required for Apollo.[23]

Manned Spacecraft Center

[edit]It became clear that managing the Apollo program would exceed the capabilities of Robert R. Gilruth's Space Task Group, which had been directing the nation's crewed space program from NASA's Langley Research Center. So Gilruth was given authority to grow his organization into a new NASA center, the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC). A site was chosen in Houston, Texas, on land donated by Rice University, and Administrator Webb announced the conversion on September 19, 1961.[24] It was also clear NASA would soon outgrow its practice of controlling missions from its Cape Canaveral Air Force Station launch facilities in Florida, so a new Mission Control Center would be included in the MSC.[25]

In September 1962, by which time two Project Mercury astronauts had orbited the Earth, Gilruth had moved his organization to rented space in Houston, and construction of the MSC facility was under way, Kennedy visited Rice to reiterate his challenge in a famous speech:

But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? ... We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills; because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win ...[26][b]

The MSC was completed in September 1963. It was renamed by the United States Congress in honor of Lyndon B. Johnson soon after his death in 1973.[27]

Launch Operations Center

[edit]It also became clear that Apollo would outgrow the Canaveral launch facilities in Florida. The two newest launch complexes were already being built for the Saturn I and IB rockets at the northernmost end: LC-34 and LC-37. But an even bigger facility would be needed for the mammoth rocket required for the crewed lunar mission, so land acquisition was started in July 1961 for a Launch Operations Center (LOC) immediately north of Canaveral at Merritt Island. The design, development and construction of the center was conducted by Kurt H. Debus, a member of Wernher von Braun's original V-2 rocket engineering team. Debus was named the LOC's first Director.[28] Construction began in November 1962. Following Kennedy's death, President Johnson issued an executive order on November 29, 1963, to rename the LOC and Cape Canaveral in honor of Kennedy.[29]

The LOC included Launch Complex 39, a Launch Control Center, and a 130-million-cubic-foot (3,700,000 m3) Vertical Assembly Building (VAB).[30] in which the space vehicle (launch vehicle and spacecraft) would be assembled on a mobile launcher platform and then moved by a crawler-transporter to one of several launch pads. Although at least three pads were planned, only two, designated A and B, were completed in October 1965. The LOC also included an Operations and Checkout Building (OCB) to which Gemini and Apollo spacecraft were initially received prior to being mated to their launch vehicles. The Apollo spacecraft could be tested in two vacuum chambers capable of simulating atmospheric pressure at altitudes up to 250,000 feet (76 km), which is nearly a vacuum.[31][32]

Organization

[edit]Administrator Webb realized that in order to keep Apollo costs under control, he had to develop greater project management skills in his organization, so he recruited George E. Mueller for a high management job. Mueller accepted, on the condition that he have a say in NASA reorganization necessary to effectively administer Apollo. Webb then worked with Associate Administrator (later Deputy Administrator) Seamans to reorganize the Office of Manned Space Flight (OMSF).[33] On July 23, 1963, Webb announced Mueller's appointment as Deputy Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, to replace then Associate Administrator D. Brainerd Holmes on his retirement effective September 1. Under Webb's reorganization, the directors of the Manned Spacecraft Center (Gilruth), Marshall Space Flight Center (von Braun), and the Launch Operations Center (Debus) reported to Mueller.[34]

Based on his industry experience on Air Force missile projects, Mueller realized some skilled managers could be found among high-ranking officers in the U.S. Air Force, so he got Webb's permission to recruit General Samuel C. Phillips, who gained a reputation for his effective management of the Minuteman program, as OMSF program controller. Phillips's superior officer Bernard A. Schriever agreed to loan Phillips to NASA, along with a staff of officers under him, on the condition that Phillips be made Apollo Program Director. Mueller agreed, and Phillips managed Apollo from January 1964, until it achieved the first human landing in July 1969, after which he returned to Air Force duty.[35]

Charles Fishman, in One Giant Leap, estimated the number of people and organizations involved into the Apollo program as "410,000 men and women at some 20,000 different companies contributed to the effort".[36]

Choosing a mission mode

[edit]

Once Kennedy had defined a goal, the Apollo mission planners were faced with the challenge of designing a spacecraft that could meet it while minimizing risk to human life, limiting cost, and not exceeding limits in possible technology and astronaut skill. Four possible mission modes were considered:

- Direct Ascent: The spacecraft would be launched as a unit and travel directly to the lunar surface, without first going into lunar orbit. A 50,000-pound (23,000 kg) Earth return ship would land all three astronauts atop a 113,000-pound (51,000 kg) descent propulsion stage,[37] which would be left on the Moon. This design would have required development of the extremely powerful Saturn C-8 or Nova launch vehicle to carry a 163,000-pound (74,000 kg) payload to the Moon.[38]

- Earth Orbit Rendezvous (EOR): Multiple rocket launches (up to 15 in some plans) would carry parts of the Direct Ascent spacecraft and propulsion units for translunar injection (TLI). These would be assembled into a single spacecraft in Earth orbit.

- Lunar Surface Rendezvous: Two spacecraft would be launched in succession. The first, an automated vehicle carrying propellant for the return to Earth, would land on the Moon, to be followed some time later by the crewed vehicle. Propellant would have to be transferred from the automated vehicle to the crewed vehicle.[39]

- Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR): This turned out to be the winning configuration, which achieved the goal with Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969: a single Saturn V launched a 96,886-pound (43,947 kg) spacecraft that was composed of a 63,608-pound (28,852 kg) Apollo command and service module which remained in orbit around the Moon and a 33,278-pound (15,095 kg) two-stage Apollo Lunar Module spacecraft which was flown by two astronauts to the surface, flown back to dock with the command module and was then discarded.[40] Landing the smaller spacecraft on the Moon, and returning an even smaller part (10,042 pounds or 4,555 kilograms) to lunar orbit, minimized the total mass to be launched from Earth, but this was the last method initially considered because of the perceived risk of rendezvous and docking.

In early 1961, direct ascent was generally the mission mode in favor at NASA. Many engineers feared that rendezvous and docking, maneuvers that had not been attempted in Earth orbit, would be nearly impossible in lunar orbit. LOR advocates including John Houbolt at Langley Research Center emphasized the important weight reductions that were offered by the LOR approach. Throughout 1960 and 1961, Houbolt campaigned for the recognition of LOR as a viable and practical option. Bypassing the NASA hierarchy, he sent a series of memos and reports on the issue to Associate Administrator Robert Seamans; while acknowledging that he spoke "somewhat as a voice in the wilderness", Houbolt pleaded that LOR should not be discounted in studies of the question.[41]

Seamans's establishment of an ad hoc committee headed by his special technical assistant Nicholas E. Golovin in July 1961, to recommend a launch vehicle to be used in the Apollo program, represented a turning point in NASA's mission mode decision.[42] This committee recognized that the chosen mode was an important part of the launch vehicle choice, and recommended in favor of a hybrid EOR-LOR mode. Its consideration of LOR—as well as Houbolt's ceaseless work—played an important role in publicizing the workability of the approach. In late 1961 and early 1962, members of the Manned Spacecraft Center began to come around to support LOR, including the newly hired deputy director of the Office of Manned Space Flight, Joseph Shea, who became a champion of LOR.[43] The engineers at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), who were heavily invested in direct ascent, took longer to become convinced of its merits, but their conversion was announced by Wernher von Braun at a briefing on June 7, 1962.[44]

But even after NASA reached internal agreement, it was far from smooth sailing. Kennedy's science advisor Jerome Wiesner, who had expressed his opposition to human spaceflight to Kennedy before the President took office,[45] and had opposed the decision to land people on the Moon, hired Golovin, who had left NASA, to chair his own "Space Vehicle Panel", ostensibly to monitor, but actually to second-guess NASA's decisions on the Saturn V launch vehicle and LOR by forcing Shea, Seamans, and even Webb to defend themselves, delaying its formal announcement to the press on July 11, 1962, and forcing Webb to still hedge the decision as "tentative".[46]

Wiesner kept up the pressure, even making the disagreement public during a two-day September visit by the President to Marshall Space Flight Center. Wiesner blurted out "No, that's no good" in front of the press, during a presentation by von Braun. Webb jumped in and defended von Braun, until Kennedy ended the squabble by stating that the matter was "still subject to final review". Webb held firm and issued a request for proposal to candidate Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) contractors. Wiesner finally relented, unwilling to settle the dispute once and for all in Kennedy's office, because of the President's involvement with the October Cuban Missile Crisis, and fear of Kennedy's support for Webb. NASA announced the selection of Grumman as the LEM contractor in November 1962.[47]

Space historian James Hansen concludes that:

Without NASA's adoption of this stubbornly held minority opinion in 1962, the United States may still have reached the Moon, but almost certainly it would not have been accomplished by the end of the 1960s, President Kennedy's target date.[48]

The LOR method had the advantage of allowing the lander spacecraft to be used as a "lifeboat" in the event of a failure of the command ship. Some documents prove this theory was discussed before and after the method was chosen. In 1964 an MSC study concluded, "The LM [as lifeboat] ... was finally dropped, because no single reasonable CSM failure could be identified that would prohibit use of the SPS."[49] Ironically, just such a failure happened on Apollo 13 when an oxygen tank explosion left the CSM without electrical power. The lunar module provided propulsion, electrical power and life support to get the crew home safely.[50]

Spacecraft

[edit]

Faget's preliminary Apollo design employed a cone-shaped command module, supported by one of several service modules providing propulsion and electrical power, sized appropriately for the space station, cislunar, and lunar landing missions. Once Kennedy's Moon landing goal became official, detailed design began of a command and service module (CSM) in which the crew would spend the entire direct-ascent mission and lift off from the lunar surface for the return trip, after being soft-landed by a larger landing propulsion module. The final choice of lunar orbit rendezvous changed the CSM's role to the translunar ferry used to transport the crew, along with a new spacecraft, the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM, later shortened to LM (Lunar Module) but still pronounced /ˈlɛm/) which would take two individuals to the lunar surface and return them to the CSM.[51]

Command and service module

[edit]

The command module (CM) was the conical crew cabin, designed to carry three astronauts from launch to lunar orbit and back to an Earth ocean landing. It was the only component of the Apollo spacecraft to survive without major configuration changes as the program evolved from the early Apollo study designs. Its exterior was covered with an ablative heat shield, and had its own reaction control system (RCS) engines to control its attitude and steer its atmospheric entry path. Parachutes were carried to slow its descent to splashdown. The module was 11.42 feet (3.48 m) tall, 12.83 feet (3.91 m) in diameter, and weighed approximately 12,250 pounds (5,560 kg).[52]

A cylindrical service module (SM) supported the command module, with a service propulsion engine and an RCS with propellants, and a fuel cell power generation system with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen reactants. A high-gain S-band antenna was used for long-distance communications on the lunar flights. On the extended lunar missions, an orbital scientific instrument package was carried. The service module was discarded just before reentry. The module was 24.6 feet (7.5 m) long and 12.83 feet (3.91 m) in diameter. The initial lunar flight version weighed approximately 51,300 pounds (23,300 kg) fully fueled, while a later version designed to carry a lunar orbit scientific instrument package weighed just over 54,000 pounds (24,000 kg).[52]

North American Aviation won the contract to build the CSM, and also the second stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle for NASA. Because the CSM design was started early before the selection of lunar orbit rendezvous, the service propulsion engine was sized to lift the CSM off the Moon, and thus was oversized to about twice the thrust required for translunar flight.[53] Also, there was no provision for docking with the lunar module. A 1964 program definition study concluded that the initial design should be continued as Block I which would be used for early testing, while Block II, the actual lunar spacecraft, would incorporate the docking equipment and take advantage of the lessons learned in Block I development.[51]

Apollo Lunar Module

[edit]

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM) was designed to descend from lunar orbit to land two astronauts on the Moon and take them back to orbit to rendezvous with the command module. Not designed to fly through the Earth's atmosphere or return to Earth, its fuselage was designed totally without aerodynamic considerations and was of an extremely lightweight construction. It consisted of separate descent and ascent stages, each with its own engine. The descent stage contained storage for the descent propellant, surface stay consumables, and surface exploration equipment. The ascent stage contained the crew cabin, ascent propellant, and a reaction control system. The initial LM model weighed approximately 33,300 pounds (15,100 kg), and allowed surface stays up to around 34 hours. An extended lunar module (ELM) weighed over 36,200 pounds (16,400 kg), and allowed surface stays of more than three days.[52] The contract for design and construction of the lunar module was awarded to Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, and the project was overseen by Thomas J. Kelly.[54]

Launch vehicles

[edit]

Before the Apollo program began, Wernher von Braun and his team of rocket engineers had started work on plans for very large launch vehicles, the Saturn series, and the even larger Nova series. In the midst of these plans, von Braun was transferred from the Army to NASA and was made Director of the Marshall Space Flight Center. The initial direct ascent plan to send the three-person Apollo command and service module directly to the lunar surface, on top of a large descent rocket stage, would require a Nova-class launcher, with a lunar payload capability of over 180,000 pounds (82,000 kg).[55] The June 11, 1962, decision to use lunar orbit rendezvous enabled the Saturn V to replace the Nova, and the MSFC proceeded to develop the Saturn rocket family for Apollo.[56]

Since Apollo, like Mercury, used more than one launch vehicle for space missions, NASA used spacecraft-launch vehicle combination series numbers: AS-10x for Saturn I, AS-20x for Saturn IB, and AS-50x for Saturn V (compare Mercury-Redstone 3, Mercury-Atlas 6) to designate and plan all missions, rather than numbering them sequentially as in Project Gemini. This was changed by the time human flights began.[57]

Little Joe II

[edit]Since Apollo, like Mercury, would require a launch escape system (LES) in case of a launch failure, a relatively small rocket was required for qualification flight testing of this system. A rocket bigger than the Little Joe used by Mercury would be required, so the Little Joe II was built by General Dynamics/Convair. After an August 1963 qualification test flight,[58] four LES test flights (A-001 through 004) were made at the White Sands Missile Range between May 1964 and January 1966.[59]

Saturn I

[edit]

Saturn I, the first US heavy lift launch vehicle, was initially planned to launch partially equipped CSMs in low Earth orbit tests. The S-I first stage burned RP-1 with liquid oxygen (LOX) oxidizer in eight clustered Rocketdyne H-1 engines, to produce 1,500,000 pounds-force (6,670 kN) of thrust. The S-IV second stage used six liquid hydrogen-fueled Pratt & Whitney RL-10 engines with 90,000 pounds-force (400 kN) of thrust. The S-V third stage flew inactively on Saturn I four times.[60]

The first four Saturn I test flights were launched from LC-34, with only the first stage live, carrying dummy upper stages filled with water. The first flight with a live S-IV was launched from LC-37. This was followed by five launches of boilerplate CSMs (designated AS-101 through AS-105) into orbit in 1964 and 1965. The last three of these further supported the Apollo program by also carrying Pegasus satellites, which verified the safety of the translunar environment by measuring the frequency and severity of micrometeorite impacts.[61]

In September 1962, NASA planned to launch four crewed CSM flights on the Saturn I from late 1965 through 1966, concurrent with Project Gemini. The 22,500-pound (10,200 kg) payload capacity[62] would have severely limited the systems which could be included, so the decision was made in October 1963 to use the uprated Saturn IB for all crewed Earth orbital flights.[63]

Saturn IB

[edit]The Saturn IB was an upgraded version of the Saturn I. The S-IB first stage increased the thrust to 1,600,000 pounds-force (7,120 kN) by uprating the H-1 engine. The second stage replaced the S-IV with the S-IVB-200, powered by a single J-2 engine burning liquid hydrogen fuel with LOX, to produce 200,000 pounds-force (890 kN) of thrust.[64] A restartable version of the S-IVB was used as the third stage of the Saturn V. The Saturn IB could send over 40,000 pounds (18,100 kg) into low Earth orbit, sufficient for a partially fueled CSM or the LM.[65] Saturn IB launch vehicles and flights were designated with an AS-200 series number, "AS" indicating "Apollo Saturn" and the "2" indicating the second member of the Saturn rocket family.[66]

Saturn V

[edit]

Saturn V launch vehicles and flights were designated with an AS-500 series number, "AS" indicating "Apollo Saturn" and the "5" indicating Saturn V.[66] The three-stage Saturn V was designed to send a fully fueled CSM and LM to the Moon. It was 33 feet (10.1 m) in diameter and stood 363 feet (110.6 m) tall with its 96,800-pound (43,900 kg) lunar payload. Its capability grew to 103,600 pounds (47,000 kg) for the later advanced lunar landings. The S-IC first stage burned RP-1/LOX for a rated thrust of 7,500,000 pounds-force (33,400 kN), which was upgraded to 7,610,000 pounds-force (33,900 kN). The second and third stages burned liquid hydrogen; the third stage was a modified version of the S-IVB, with thrust increased to 230,000 pounds-force (1,020 kN) and capability to restart the engine for translunar injection after reaching a parking orbit.[67]

Astronauts

[edit]

NASA's director of flight crew operations during the Apollo program was Donald K. "Deke" Slayton, one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts who was medically grounded in September 1962 due to a heart murmur. Slayton was responsible for making all Gemini and Apollo crew assignments.[68]

Thirty-two astronauts were assigned to fly missions in the Apollo program. Twenty-four of these left Earth's orbit and flew around the Moon between December 1968 and December 1972 (three of them twice). Half of the 24 walked on the Moon's surface, though none of them returned to it after landing once. One of the moonwalkers was a trained geologist. Of the 32, Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee were killed during a ground test in preparation for the Apollo 1 mission.[57]

The Apollo astronauts were chosen from the Project Mercury and Gemini veterans, plus from two later astronaut groups. All missions were commanded by Gemini or Mercury veterans. Crews on all development flights (except the Earth orbit CSM development flights) through the first two landings on Apollo 11 and Apollo 12, included at least two (sometimes three) Gemini veterans. Harrison Schmitt, a geologist, was the first NASA scientist astronaut to fly in space, and landed on the Moon on the last mission, Apollo 17. Schmitt participated in the lunar geology training of all of the Apollo landing crews.[69]

NASA awarded all 32 of these astronauts its highest honor, the Distinguished Service Medal, given for "distinguished service, ability, or courage", and personal "contribution representing substantial progress to the NASA mission". The medals were awarded posthumously to Grissom, White, and Chaffee in 1969, then to the crews of all missions from Apollo 8 onward. The crew that flew the first Earth orbital test mission Apollo 7, Walter M. Schirra, Donn Eisele, and Walter Cunningham, were awarded the lesser NASA Exceptional Service Medal, because of discipline problems with the flight director's orders during their flight. In October 2008, the NASA Administrator decided to award them the Distinguished Service Medals. For Schirra and Eisele, this was posthumously.[70]

Lunar mission profile

[edit]The first lunar landing mission was planned to proceed:[71]

-

Launch The three Saturn V stages burn for about 11 minutes to achieve a 100-nautical-mile (190 km) circular parking orbit. The third stage burns a small portion of its fuel to achieve orbit.

-

Translunar injection After one to two orbits to verify readiness of spacecraft systems, the S-IVB third stage reignites for about six minutes to send the spacecraft to the Moon.

-

Transposition and docking The Spacecraft Lunar Module Adapter (SLA) panels separate to free the CSM and expose the LM. The command module pilot (CMP) moves the CSM out a safe distance, and turns 180°.

-

Extraction The CMP docks the CSM with the LM, and pulls the complete spacecraft away from the S-IVB. The lunar voyage takes between two and three days. Midcourse corrections are made as necessary using the SM engine.

-

Lunar orbit insertion The spacecraft passes about 60 nautical miles (110 km) behind the Moon, and the SM engine is fired to slow the spacecraft and put it into a 60-by-170-nautical-mile (110 by 310 km) orbit, which is soon circularized at 60 nautical miles by a second burn.

-

After a rest period, the commander (CDR) and lunar module pilot (LMP) move to the LM, power up its systems, and deploy the landing gear. The CSM and LM separate; the CMP visually inspects the LM, then the LM crew move a safe distance away and fire the descent engine for Descent orbit insertion, which takes it to a perilune of about 50,000 feet (15 km).

-

Powered descent At perilune, the descent engine fires again to start the descent. The CDR takes control after pitchover for a vertical landing.

-

The CDR and LMP perform one or more EVAs exploring the lunar surface and collecting samples, alternating with rest periods.

-

The ascent stage lifts off, using the descent stage as a launching pad.

-

The LM rendezvouses and docks with the CSM.

-

The CDR and LMP transfer back to the CM with their material samples, then the LM ascent stage is jettisoned, to eventually fall out of orbit and crash on the surface.

-

Trans-Earth injection The SM engine fires to send the CSM back to Earth.

-

The SM is jettisoned just before reentry, and the CM turns 180° to face its blunt end forward for reentry.

-

Atmospheric drag slows the CM. Aerodynamic heating surrounds it with an envelope of ionized air which causes a communications blackout for several minutes.

-

Parachutes are deployed, slowing the CM for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean. The astronauts are recovered and brought to an aircraft carrier.

Profile variations

[edit]- The first three lunar missions (Apollo 8, Apollo 10, and Apollo 11) used a free return trajectory, keeping a flight path coplanar with the lunar orbit, which would allow a return to Earth in case the SM engine failed to make lunar orbit insertion. Landing site lighting conditions on later missions dictated a lunar orbital plane change, which required a course change maneuver soon after TLI, and eliminated the free-return option.[72]

- After Apollo 12 placed the second of several seismometers on the Moon,[73] the jettisoned LM ascent stages on Apollo 12 and later missions were deliberately crashed on the Moon at known locations to induce vibrations in the Moon's structure. The only exceptions to this were the Apollo 13 LM which burned up in the Earth's atmosphere, and Apollo 16, where a loss of attitude control after jettison prevented making a targeted impact.[74]

- As another active seismic experiment, the S-IVBs on Apollo 13 and subsequent missions were deliberately crashed on the Moon instead of being sent to solar orbit.[75]

- Starting with Apollo 13, descent orbit insertion was to be performed using the service module engine instead of the LM engine, in order to allow a greater fuel reserve for landing. This was actually done for the first time on Apollo 14, since the Apollo 13 mission was aborted before landing.[76]

Development history

[edit]Uncrewed flight tests

[edit]

Two Block I CSMs were launched from LC-34 on suborbital flights in 1966 with the Saturn IB. The first, AS-201 launched on February 26, reached an altitude of 265.7 nautical miles (492.1 km) and splashed down 4,577 nautical miles (8,477 km) downrange in the Atlantic Ocean.[77] The second, AS-202 on August 25, reached 617.1 nautical miles (1,142.9 km) altitude and was recovered 13,900 nautical miles (25,700 km) downrange in the Pacific Ocean. These flights validated the service module engine and the command module heat shield.[78]

A third Saturn IB test, AS-203 launched from pad 37, went into orbit to support design of the S-IVB upper stage restart capability needed for the Saturn V. It carried a nose cone instead of the Apollo spacecraft, and its payload was the unburned liquid hydrogen fuel, the behavior of which engineers measured with temperature and pressure sensors, and a TV camera. This flight occurred on July 5, before AS-202, which was delayed because of problems getting the Apollo spacecraft ready for flight.[79]

Preparation for crewed flight

[edit]Two crewed orbital Block I CSM missions were planned: AS-204 and AS-205. The Block I crew positions were titled Command Pilot, Senior Pilot, and Pilot. The Senior Pilot would assume navigation duties, while the Pilot would function as a systems engineer.[80] The astronauts would wear a modified version of the Gemini spacesuit.[81]

After an uncrewed LM test flight AS-206, a crew would fly the first Block II CSM and LM in a dual mission known as AS-207/208, or AS-278 (each spacecraft would be launched on a separate Saturn IB).[82] The Block II crew positions were titled Commander, Command Module Pilot, and Lunar Module Pilot. The astronauts would begin wearing a new Apollo A6L spacesuit, designed to accommodate lunar extravehicular activity (EVA). The traditional visor helmet was replaced with a clear "fishbowl" type for greater visibility, and the lunar surface EVA suit would include a water-cooled undergarment.[83]

Deke Slayton, the grounded Mercury astronaut who became director of flight crew operations for the Gemini and Apollo programs, selected the first Apollo crew in January 1966, with Grissom as Command Pilot, White as Senior Pilot, and rookie Donn F. Eisele as Pilot. But Eisele dislocated his shoulder twice aboard the KC135 weightlessness training aircraft, and had to undergo surgery on January 27. Slayton replaced him with Chaffee.[84] NASA announced the final crew selection for AS-204 on March 21, 1966, with the backup crew consisting of Gemini veterans James McDivitt and David Scott, with rookie Russell L. "Rusty" Schweickart. Mercury/Gemini veteran Wally Schirra, Eisele, and rookie Walter Cunningham were announced on September 29 as the prime crew for AS-205.[84]

In December 1966, the AS-205 mission was canceled, since the validation of the CSM would be accomplished on the 14-day first flight, and AS-205 would have been devoted to space experiments and contribute no new engineering knowledge about the spacecraft. Its Saturn IB was allocated to the dual mission, now redesignated AS-205/208 or AS-258, planned for August 1967. McDivitt, Scott and Schweickart were promoted to the prime AS-258 crew, and Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham were reassigned as the Apollo 1 backup crew.[85]

Program delays

[edit]The spacecraft for the AS-202 and AS-204 missions were delivered by North American Aviation to the Kennedy Space Center with long lists of equipment problems which had to be corrected before flight; these delays caused the launch of AS-202 to slip behind AS-203, and eliminated hopes the first crewed mission might be ready to launch as soon as November 1966, concurrently with the last Gemini mission. Eventually, the planned AS-204 flight date was pushed to February 21, 1967.[86]

North American Aviation was prime contractor not only for the Apollo CSM, but for the Saturn V S-II second stage as well, and delays in this stage pushed the first uncrewed Saturn V flight AS-501 from late 1966 to November 1967. (The initial assembly of AS-501 had to use a dummy spacer spool in place of the stage.)[87]

The problems with North American were severe enough in late 1965 to cause Manned Space Flight Administrator George Mueller to appoint program director Samuel Phillips to head a "tiger team" to investigate North American's problems and identify corrections. Phillips documented his findings in a December 19 letter to NAA president Lee Atwood, with a strongly worded letter by Mueller, and also gave a presentation of the results to Mueller and Deputy Administrator Robert Seamans.[88] Meanwhile, Grumman was also encountering problems with the Lunar Module, eliminating hopes it would be ready for crewed flight in 1967, not long after the first crewed CSM flights.[89]

Apollo 1 fire

[edit]

Grissom, White, and Chaffee decided to name their flight Apollo 1 as a motivational focus on the first crewed flight. They trained and conducted tests of their spacecraft at North American, and in the altitude chamber at the Kennedy Space Center. A "plugs-out" test was planned for January, which would simulate a launch countdown on LC-34 with the spacecraft transferring from pad-supplied to internal power. If successful, this would be followed by a more rigorous countdown simulation test closer to the February 21 launch, with both spacecraft and launch vehicle fueled.[90]

The plugs-out test began on the morning of January 27, 1967, and immediately was plagued with problems. First, the crew noticed a strange odor in their spacesuits which delayed the sealing of the hatch. Then, communications problems frustrated the astronauts and forced a hold in the simulated countdown. During this hold, an electrical fire began in the cabin and spread quickly in the high pressure, 100% oxygen atmosphere. Pressure rose high enough from the fire that the cabin inner wall burst, allowing the fire to erupt onto the pad area and frustrating attempts to rescue the crew. The astronauts were asphyxiated before the hatch could be opened.[91]

NASA immediately convened an accident review board, overseen by both houses of Congress. While the determination of responsibility for the accident was complex, the review board concluded that "deficiencies existed in command module design, workmanship and quality control".[91] At the insistence of NASA Administrator Webb, North American removed Harrison Storms as command module program manager.[92] Webb also reassigned Apollo Spacecraft Program Office (ASPO) Manager Joseph Francis Shea, replacing him with George Low.[93]

To remedy the causes of the fire, changes were made in the Block II spacecraft and operational procedures, the most important of which were use of a nitrogen/oxygen mixture instead of pure oxygen before and during launch, and removal of flammable cabin and space suit materials.[94] The Block II design already called for replacement of the Block I plug-type hatch cover with a quick-release, outward opening door.[94] NASA discontinued the crewed Block I program, using the Block I spacecraft only for uncrewed Saturn V flights. Crew members would also exclusively wear modified, fire-resistant A7L Block II space suits, and would be designated by the Block II titles, regardless of whether a LM was present on the flight or not.[83]

Uncrewed Saturn V and LM tests

[edit]On April 24, 1967, Mueller published an official Apollo mission numbering scheme, using sequential numbers for all flights, crewed or uncrewed. The sequence would start with Apollo 4 to cover the first three uncrewed flights while retiring the Apollo 1 designation to honor the crew, per their widows' wishes.[57][95]

In September 1967, Mueller approved a sequence of mission types which had to be accomplished in order to achieve the crewed lunar landing. Each step had to be accomplished before the next ones could be performed, and it was unknown how many tries of each mission would be necessary; therefore letters were used instead of numbers. The A missions were uncrewed Saturn V validation; B was uncrewed LM validation using the Saturn IB; C was crewed CSM Earth orbit validation using the Saturn IB; D was the first crewed CSM/LM flight (this replaced AS-258, using a single Saturn V launch); E would be a higher Earth orbit CSM/LM flight; F would be the first lunar mission, testing the LM in lunar orbit but without landing (a "dress rehearsal"); and G would be the first crewed landing. The list of types covered follow-on lunar exploration to include H lunar landings, I for lunar orbital survey missions, and J for extended-stay lunar landings.[96]

The delay in the CSM caused by the fire enabled NASA to catch up on human-rating the LM and Saturn V. Apollo 4 (AS-501) was the first uncrewed flight of the Saturn V, carrying a Block I CSM on November 9, 1967. The capability of the command module's heat shield to survive a trans-lunar reentry was demonstrated by using the service module engine to ram it into the atmosphere at higher than the usual Earth-orbital reentry speed.

Apollo 5 (AS-204) was the first uncrewed test flight of the LM in Earth orbit, launched from pad 37 on January 22, 1968, by the Saturn IB that would have been used for Apollo 1. The LM engines were successfully test-fired and restarted, despite a computer programming error, which cut short the first descent stage firing. The ascent engine was fired in abort mode, known as a "fire-in-the-hole" test, where it was lit simultaneously with jettison of the descent stage. Although Grumman wanted a second uncrewed test, George Low decided the next LM flight would be crewed.[97]

This was followed on April 4, 1968, by Apollo 6 (AS-502) which carried a CSM and a LM Test Article as ballast. The intent of this mission was to achieve trans-lunar injection, followed closely by a simulated direct-return abort, using the service module engine to achieve another high-speed reentry. The Saturn V experienced pogo oscillation, a problem caused by non-steady engine combustion, which damaged fuel lines in the second and third stages. Two S-II engines shut down prematurely, but the remaining engines were able to compensate. The damage to the third stage engine was more severe, preventing it from restarting for trans-lunar injection. Mission controllers were able to use the service module engine to essentially repeat the flight profile of Apollo 4. Based on the good performance of Apollo 6 and identification of satisfactory fixes to the Apollo 6 problems, NASA declared the Saturn V ready to fly crew, canceling a third uncrewed test.[98]

Crewed development missions

[edit]

Apollo 7, launched from LC-34 on October 11, 1968, was the C mission, crewed by Schirra, Eisele, and Cunningham. It was an 11-day Earth-orbital flight which tested the CSM systems.[99]

Apollo 8 was planned to be the D mission in December 1968, crewed by McDivitt, Scott and Schweickart, launched on a Saturn V instead of two Saturn IBs.[100] In the summer it had become clear that the LM would not be ready in time. Rather than waste the Saturn V on another simple Earth-orbiting mission, ASPO Manager George Low suggested the bold step of sending Apollo 8 to orbit the Moon instead, deferring the D mission to the next mission in March 1969, and eliminating the E mission. This would keep the program on track. The Soviet Union had sent two tortoises, mealworms, wine flies, and other lifeforms around the Moon on September 15, 1968, aboard Zond 5, and it was believed they might soon repeat the feat with human cosmonauts.[101][102] The decision was not announced publicly until completion of Apollo 7. Gemini veterans Frank Borman and Jim Lovell, and rookie William Anders captured the world's attention by making ten lunar orbits in 20 hours, transmitting television pictures of the lunar surface on Christmas Eve, and returning safely to Earth.[103]

The following March, LM flight, rendezvous and docking were demonstrated in Earth orbit on Apollo 9, and Schweickart tested the full lunar EVA suit with its portable life support system (PLSS) outside the LM.[104] The F mission was carried out on Apollo 10 in May 1969 by Gemini veterans Thomas P. Stafford, John Young and Eugene Cernan. Stafford and Cernan took the LM to within 50,000 feet (15 km) of the lunar surface.[105]

The G mission was achieved on Apollo 11 in July 1969 by an all-Gemini veteran crew consisting of Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin. Armstrong and Aldrin performed the first landing at the Sea of Tranquility at 20:17:40 UTC on July 20, 1969. They spent a total of 21 hours, 36 minutes on the surface, and spent 2 hours, 31 minutes outside the spacecraft,[106] walking on the surface, taking photographs, collecting material samples, and deploying automated scientific instruments, while continuously sending black-and-white television back to Earth. The astronauts returned safely on July 24.[107]

That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.

— Neil Armstrong, just after stepping onto the Moon's surface[108]

Production lunar landings

[edit]In November 1969, Charles "Pete" Conrad became the third person to step onto the Moon, which he did while speaking more informally than had Armstrong:

Whoopee! Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that's a long one for me.

— Pete Conrad[109]

Conrad and rookie Alan L. Bean made a precision landing of Apollo 12 within walking distance of the Surveyor 3 uncrewed lunar probe, which had landed in April 1967 on the Ocean of Storms. The command module pilot was Gemini veteran Richard F. Gordon Jr. Conrad and Bean carried the first lunar surface color television camera, but it was damaged when accidentally pointed into the Sun. They made two EVAs totaling 7 hours and 45 minutes.[106] On one, they walked to the Surveyor, photographed it, and removed some parts which they returned to Earth.[110]

The contracted batch of 15 Saturn Vs was enough for lunar landing missions through Apollo 20. Shortly after Apollo 11, NASA publicized a preliminary list of eight more planned landing sites after Apollo 12, with plans to increase the mass of the CSM and LM for the last five missions, along with the payload capacity of the Saturn V. These final missions would combine the I and J types in the 1967 list, allowing the CMP to operate a package of lunar orbital sensors and cameras while his companions were on the surface, and allowing them to stay on the Moon for over three days. These missions would also carry the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) increasing the exploration area and allowing televised liftoff of the LM. Also, the Block II spacesuit was revised for the extended missions to allow greater flexibility and visibility for driving the LRV.[111]

The success of the first two landings allowed the remaining missions to be crewed with a single veteran as commander, with two rookies. Apollo 13 launched Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise in April 1970, headed for the Fra Mauro formation. But two days out, a liquid oxygen tank exploded, disabling the service module and forcing the crew to use the LM as a "lifeboat" to return to Earth. Another NASA review board was convened to determine the cause, which turned out to be a combination of damage of the tank in the factory, and a subcontractor not making a tank component according to updated design specifications.[50] Apollo was grounded again, for the remainder of 1970 while the oxygen tank was redesigned and an extra one was added.[112]

Mission cutbacks

[edit]About the time of the first landing in 1969, it was decided to use an existing Saturn V to launch the Skylab orbital laboratory pre-built on the ground, replacing the original plan to construct it in orbit from several Saturn IB launches; this eliminated Apollo 20. NASA's yearly budget also began to shrink in light of the landing, and NASA also had to make funds available for the development of the upcoming Space Shuttle. By 1971, the decision was made to also cancel missions 18 and 19.[113] The two unused Saturn Vs became museum exhibits at the John F. Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island, Florida, George C. Marshall Space Center in Huntsville, Alabama, Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.[114]

The cutbacks forced mission planners to reassess the original planned landing sites in order to achieve the most effective geological sample and data collection from the remaining four missions. Apollo 15 had been planned to be the last of the H series missions, but since there would be only two subsequent missions left, it was changed to the first of three J missions.[115]

Apollo 13's Fra Mauro mission was reassigned to Apollo 14, commanded in February 1971 by Mercury veteran Alan Shepard, with Stuart Roosa and Edgar Mitchell.[116] This time the mission was successful. Shepard and Mitchell spent 33 hours and 31 minutes on the surface,[117] and completed two EVAs totalling 9 hours 24 minutes, which was a record for the longest EVA by a lunar crew at the time.[116]

In August 1971, just after conclusion of the Apollo 15 mission, President Richard Nixon proposed canceling the two remaining lunar landing missions, Apollo 16 and 17. Office of Management and Budget Deputy Director Caspar Weinberger was opposed to this, and persuaded Nixon to keep the remaining missions.[118]

Extended missions

[edit]

Apollo 15 was launched on July 26, 1971, with David Scott, Alfred Worden and James Irwin. Scott and Irwin landed on July 30 near Hadley Rille, and spent just under two days, 19 hours on the surface. In over 18 hours of EVA, they collected about 77 kilograms (170 lb) of lunar material.[119]

Apollo 16 landed in the Descartes Highlands on April 20, 1972. The crew was commanded by John Young, with Ken Mattingly and Charles Duke. Young and Duke spent just under three days on the surface, with a total of over 20 hours EVA.[120]

Apollo 17 was the last of the Apollo program, landing in the Taurus–Littrow region in December 1972. Eugene Cernan commanded Ronald E. Evans and NASA's first scientist-astronaut, geologist Harrison H. Schmitt.[121] Schmitt was originally scheduled for Apollo 18,[122] but the lunar geological community lobbied for his inclusion on the final lunar landing.[123] Cernan and Schmitt stayed on the surface for just over three days and spent just over 23 hours of total EVA.[121]

Canceled missions

[edit]Several missions were planned for but were canceled before details were finalized.

Mission summary

[edit]| Designation | Date | LV | CSM | LM | Crew | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS-201 | Feb 26, 1966 | AS-201 | CSM-009 | — | — | First flight of Saturn IB and Block I CSM; suborbital to Atlantic Ocean; qualified heat shield to orbital reentry speed. |

| AS-203 | Jul 5, 1966 | AS-203 | — | — | — | No spacecraft; observations of liquid hydrogen fuel behavior in orbit to support design of S-IVB restart capability. |

| AS-202 | Aug 25, 1966 | AS-202 | CSM-011 | — | — | Suborbital flight of CSM to Pacific Ocean. |

| Apollo 1 | Feb 21, 1967 | SA-204 | CSM-012 | — | Gus Grissom Ed White Roger B. Chaffee |

Not flown. All crew members died in a fire during a launch pad test on January 27, 1967. |

| Apollo 4 | Nov 9, 1967 | SA-501 | CSM-017 | LTA-10R | — | First test flight of Saturn V, placed a CSM in a high Earth orbit; demonstrated S-IVB restart; qualified CM heat shield to lunar reentry speed. |

| Apollo 5 | Jan 22–23, 1968 | SA-204 | — | LM-1 | — | Earth orbital flight test of LM, launched on Saturn IB; demonstrated ascent and descent propulsion; human-rated the LM. No crew. |

| Apollo 6 | Apr 4, 1968 | SA-502 | CM-020 SM-014 |

LTA-2R | — | Uncrewed, second flight of Saturn V, attempted demonstration of trans-lunar injection, and direct-return abort using SM engine; three engine failures, including failure of S-IVB restart. Flight controllers used SM engine to repeat Apollo 4's flight profile. Human-rated the Saturn V. |

| Apollo 7 | Oct 11–22, 1968 | SA-205 | CSM-101 | — | Wally Schirra Walt Cunningham Donn Eisele |

First crewed Earth orbital demonstration of Block II CSM, launched on Saturn IB. First live television broadcast from a crewed mission. |

| Apollo 8 | Dec 21–27, 1968 | SA-503 | CSM-103 | LTA-B | Frank Borman James Lovell William Anders |

First crewed flight of Saturn V; First crewed flight to Moon; CSM made 10 lunar orbits in 20 hours. |

| Apollo 9 | Mar 3–13, 1969 | SA-504 | CSM-104 Gumdrop |

LM-3 Spider |

James McDivitt David Scott Russell Schweickart |

Second crewed flight of Saturn V; First crewed flight of CSM and LM in Earth orbit; demonstrated portable life support system to be used on the lunar surface. |

| Apollo 10 | May 18–26, 1969 | SA-505 | CSM-106 Charlie Brown |

LM-4 Snoopy |

Thomas Stafford John Young Eugene Cernan |

Dress rehearsal for first lunar landing; flew LM down to 50,000 ft (15 km; 9.5 mi) from lunar surface. |

| Apollo 11 | Jul 16–24, 1969 | SA-506 | CSM-107 Columbia |

LM-5 Eagle | Neil Armstrong Michael Collins Buzz Aldrin |

First landing, in Tranquility Base, Sea of Tranquility. Surface EVA time: 2h 31m. Samples returned: 47.51 lb (21.55 kg). |

| Apollo 12 | Nov 14–24, 1969 | SA-507 | CSM-108 Yankee Clipper |

LM-6 Intrepid |

Pete Conrad Richard Gordon Alan Bean |

Second landing, in Ocean of Storms near Surveyor 3. Surface EVA time: 7h 45m. Samples returned: 75.62 lb (34.30 kg). |

| Apollo 13 | Apr 11–17, 1970 | SA-508 | CSM-109 Odyssey |

LM-7 Aquarius |

James Lovell Jack Swigert Fred Haise |

Third landing attempt aborted in transit to the Moon, due to SM failure. Crew used LM as "lifeboat" to return to Earth. Mission called a "successful failure".[124] |

| Apollo 14 | Jan 31 – Feb 9, 1971 | SA-509 | CSM-110 Kitty Hawk |

LM-8 Antares |

Alan Shepard Stuart Roosa Edgar Mitchell |

Third landing, in Fra Mauro formation. Surface EVA time: 9h 21m. Samples returned: 94.35 lb (42.80 kg). |

| Apollo 15 | Jul 26 – Aug 7, 1971 | SA-510 | CSM-112 Endeavour |

LM-10 Falcon |

David Scott Alfred Worden James Irwin |

Fourth landing, in Hadley-Apennine. First extended mission, used Rover on Moon. Surface EVA time: 18h 33m. Samples returned: 169.10 lb (76.70 kg). |

| Apollo 16 | Apr 16–27, 1972 | SA-511 | CSM-113 Casper |

LM-11 Orion |

John Young Ken Mattingly Charles Duke |

Fifth landing, in Plain of Descartes. Second extended mission, used Rover on Moon. Surface EVA time: 20h 14m. Samples returned: 207.89 lb (94.30 kg). |

| Apollo 17 | Dec 7–19, 1972 | SA-512 | CSM-114 America |

LM-12 Challenger |

Eugene Cernan Ronald Evans Harrison Schmitt |

Only Saturn V night launch. Sixth landing, in Taurus–Littrow. Third extended mission, used Rover on Moon. First geologist on the Moon. Apollo's last crewed Moon landing. Surface EVA time: 22h 2m. Samples returned: 243.40 lb (110.40 kg). |

Source: Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference (Orloff 2004).[125]

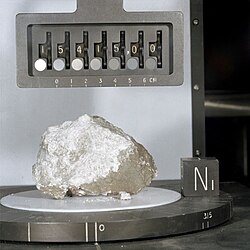

Samples returned

[edit]The Apollo program returned over 382 kg (842 lb) of lunar rocks and soil to the Lunar Receiving Laboratory in Houston.[126][125][127] Today, 75% of the samples are stored at the Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility built in 1979.[128]

The rocks collected from the Moon are extremely old compared to rocks found on Earth, as measured by radiometric dating techniques. They range in age from about 3.2 billion years for the basaltic samples derived from the lunar maria, to about 4.6 billion years for samples derived from the highlands crust.[129] As such, they represent samples from a very early period in the development of the Solar System, that are largely absent on Earth. One important rock found during the Apollo Program is dubbed the Genesis Rock, retrieved by astronauts David Scott and James Irwin during the Apollo 15 mission.[130] This anorthosite rock is composed almost exclusively of the calcium-rich feldspar mineral anorthite, and is believed to be representative of the highland crust.[131] A geochemical component called KREEP was discovered by Apollo 12, which has no known terrestrial counterpart.[132] KREEP and the anorthositic samples have been used to infer that the outer portion of the Moon was once completely molten (see lunar magma ocean).[133]

Almost all the rocks show evidence of impact process effects. Many samples appear to be pitted with micrometeoroid impact craters, which is never seen on Earth rocks, due to the thick atmosphere. Many show signs of being subjected to high-pressure shock waves that are generated during impact events. Some of the returned samples are of impact melt (materials melted near an impact crater.) All samples returned from the Moon are highly brecciated as a result of being subjected to multiple impact events.[134]

From analyses of the composition of the returned lunar samples, it is now believed that the Moon was created through the impact of a large astronomical body with Earth.[135]

Costs

[edit]Apollo cost $25.4 billion or approximately $257 billion (2023) using improved cost analysis.[136]

Of this amount, $20.2 billion ($149 billion adjusted) was spent on the design, development, and production of the Saturn family of launch vehicles, the Apollo spacecraft, spacesuits, scientific experiments, and mission operations. The cost of constructing and operating Apollo-related ground facilities, such as the NASA human spaceflight centers and the global tracking and data acquisition network, added an additional $5.2 billion ($38.3 billion adjusted).

The amount grows to $28 billion ($280 billion adjusted) if the costs for related projects such as Project Gemini and the robotic Ranger, Surveyor, and Lunar Orbiter programs are included.[1]

NASA's official cost breakdown, as reported to Congress in the Spring of 1973, is as follows:

| Project Apollo | Cost (original, billion $) |

|---|---|

| Apollo spacecraft | 8.5 |

| Saturn launch vehicles | 9.1 |

| Launch vehicle engine development | 0.9 |

| Operations | 1.7 |

| Total R&D | 20.2 |

| Tracking and data acquisition | 0.9 |

| Ground facilities | 1.8 |

| Operation of installations | 2.5 |

| Total | 25.4 |

Accurate estimates of human spaceflight costs were difficult in the early 1960s, as the capability was new and management experience was lacking. Preliminary cost analysis by NASA estimated $7 billion – $12 billion for a crewed lunar landing effort. NASA Administrator James Webb increased this estimate to $20 billion before reporting it to Vice President Johnson in April 1961.[137]

Project Apollo was a massive undertaking, representing the largest research and development project in peacetime. At its peak, it employed over 400,000 employees and contractors around the country and accounted for more than half of NASA's total spending in the 1960s.[138] After the first Moon landing, public and political interest waned, including that of President Nixon, who wanted to rein in federal spending.[139] NASA's budget could not sustain Apollo missions which cost, on average, $445 million ($2.73 billion adjusted)[140] each while simultaneously developing the Space Shuttle. The final fiscal year of Apollo funding was 1973.

Apollo Applications Program

[edit]Looking beyond the crewed lunar landings, NASA investigated several post-lunar applications for Apollo hardware. The Apollo Extension Series (Apollo X) proposed up to 30 flights to Earth orbit, using the space in the Spacecraft Lunar Module Adapter (SLA) to house a small orbital laboratory (workshop). Astronauts would continue to use the CSM as a ferry to the station. This study was followed by design of a larger orbital workshop to be built in orbit from an empty S-IVB Saturn upper stage and grew into the Apollo Applications Program (AAP). The workshop was to be supplemented by the Apollo Telescope Mount, which could be attached to the ascent stage of the lunar module via a rack.[141] The most ambitious plan called for using an empty S-IVB as an interplanetary spacecraft for a Venus fly-by mission.[142]

The S-IVB orbital workshop was the only one of these plans to make it off the drawing board. Dubbed Skylab, it was assembled on the ground rather than in space, and launched in 1973 using the two lower stages of a Saturn V. It was equipped with an Apollo Telescope Mount. Skylab's last crew departed the station on February 8, 1974, and the station itself re-entered the atmosphere in 1979 after development of the Space Shuttle was delayed too long to save it.[143][144]

The Apollo–Soyuz program also used Apollo hardware for the first joint nation spaceflight, paving the way for future cooperation with other nations in the Space Shuttle and International Space Station programs.[144][145]

Recent observations

[edit]

In 2008, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's SELENE probe observed evidence of the halo surrounding the Apollo 15 Lunar Module blast crater while orbiting above the lunar surface.[146]

Beginning in 2009, NASA's robotic Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, while orbiting 50 kilometers (31 mi) above the Moon, photographed the remnants of the Apollo program left on the lunar surface, and each site where crewed Apollo flights landed.[147][148] All of U.S. flags left on the Moon during the Apollo missions were found to still be standing, with the exception of the one left during the Apollo 11 mission, which was blown over during that mission's lift-off from the lunar surface; the degree to which these flags retain their original colors remains unknown.[149] The flags cannot be seen through a telescope from Earth.

In a November 16, 2009, editorial, The New York Times opined:

[T]here's something terribly wistful about these photographs of the Apollo landing sites. The detail is such that if Neil Armstrong were walking there now, we could make him out, make out his footsteps even, like the astronaut footpath clearly visible in the photos of the Apollo 14 site. Perhaps the wistfulness is caused by the sense of simple grandeur in those Apollo missions. Perhaps, too, it's a reminder of the risk we all felt after the Eagle had landed—the possibility that it might be unable to lift off again and the astronauts would be stranded on the Moon. But it may also be that a photograph like this one is as close as we're able to come to looking directly back into the human past ... There the [Apollo 11] lunar module sits, parked just where it landed 40 years ago, as if it still really were 40 years ago and all the time since merely imaginary.[150]

Legacy

[edit]Science and engineering

[edit]

The Apollo program has been described as the greatest technological achievement in human history.[151] Apollo stimulated many areas of technology, leading to over 1,800 spinoff products as of 2015, including advances in the development of cordless power tools, fireproof materials, heart monitors, solar panels, digital imaging, and the use of liquid methane as fuel.[152][153][154] The flight computer design used in both the lunar and command modules was, along with the Polaris and Minuteman missile systems, the driving force behind early research into integrated circuits (ICs). By 1963, Apollo was using 60 percent of the United States' production of ICs. The crucial difference between the requirements of Apollo and the missile programs was Apollo's much greater need for reliability. While the Navy and Air Force could work around reliability problems by deploying more missiles, the political and financial cost of failure of an Apollo mission was unacceptably high.[155]

Technologies and techniques required for Apollo were developed by Project Gemini.[156] The Apollo project was enabled by NASA's adoption of new advances in semiconductor electronic technology, including metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) in the Interplanetary Monitoring Platform (IMP)[157][158] and silicon integrated circuit chips in the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC).[159]

Cultural impact

[edit]

The crew of Apollo 8 sent the first live televised pictures of the Earth and the Moon back to Earth, and read from the creation story in the Book of Genesis, on Christmas Eve 1968.[160] An estimated one-quarter of the population of the world saw—either live or delayed—the Christmas Eve transmission during the ninth orbit of the Moon,[161] and an estimated one-fifth of the population of the world watched the live transmission of the Apollo 11 moonwalk.[162]

The Apollo program also affected environmental activism in the 1970s due to photos taken by the astronauts. The most well known include Earthrise, taken by William Anders on Apollo 8, and The Blue Marble, taken by the Apollo 17 astronauts. The Blue Marble was released during a surge in environmentalism, and became a symbol of the environmental movement as a depiction of Earth's frailty, vulnerability, and isolation amid the vast expanse of space.[163]

According to The Economist, Apollo succeeded in accomplishing President Kennedy's goal of taking on the Soviet Union in the Space Race by accomplishing a singular and significant achievement, to demonstrate the superiority of the free-market system. The publication noted the irony that in order to achieve the goal, the program required the organization of tremendous public resources within a vast, centralized government bureaucracy.[164]

Apollo 11 broadcast data restoration project

[edit]Prior to Apollo 11's 40th anniversary in 2009, NASA searched for the original videotapes of the mission's live televised moonwalk. After an exhaustive three-year search, it was concluded that the tapes had probably been erased and reused. A new digitally remastered version of the best available broadcast television footage was released instead.[165]

Depictions on film

[edit]Documentaries

[edit]Numerous documentary films cover the Apollo program and the Space Race, including:

- Footprints on the Moon (1969)

- Moonwalk One (1970)[166]

- The Greatest Adventure (1978)[167]

- For All Mankind (1989)[168]

- Moon Shot (1994 miniseries)

- "Moon" from the BBC miniseries The Planets (1999)

- Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D (2005)

- The Wonder of It All (2007)

- In the Shadow of the Moon (2007)[169]

- When We Left Earth: The NASA Missions (2008 miniseries)

- Moon Machines (2008 miniseries)

- James May on the Moon (2009)

- NASA's Story (2009 miniseries)

- Apollo 11 (2019)[170][171]

- Chasing the Moon (2019 miniseries)

Docudramas

[edit]Some missions have been dramatized:

- Apollo 13 (1995)

- Apollo 11 (1996)

- From the Earth to the Moon (1998)

- The Dish (2000)

- Space Race (2005)

- Moonshot (2009)

- First Man (2018)

Fictional

[edit]The Apollo program has been the focus of several works of fiction, including:

- Apollo 18 (2011), horror movie which was released to negative reviews.

- Transformers: Dark of the Moon (2011), Science Fiction/Action movie. The film depicts the Apollo Program as having been created to study and explore a Cybertronian spacecraft known as "The Ark," which crash landed on the dark side of the Moon in the early 1960s.

- Men in Black 3 (2012), Science Fiction/Comedy movie. Agent J, played by Will Smith, goes back to the Apollo 11 launch in 1969 to ensure that a global protection system is launched in to space.

- For All Mankind (2019), TV series depicting an alternate history in which the Soviet Union was the first nation to land a man on the Moon and the Apollo missions were expanded as part of an accelerated Space Race, culminating in the establishment of a permanent US Moon base called Jamestown.

- Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023), fifth Indiana Jones film, in which Jürgen Voller, a NASA member and ex-Nazi involved with the Apollo program, wants to time travel. The New York City parade for the Apollo 11 crew is portrayed as a plot point.[172]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "How much did the Apollo program cost?". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on April 1, 2025. Retrieved March 25, 2024.

- ^ Murray & Cox 1989, p. 55.

- ^ Kelsey, Charles E. (July 14, 1969). "1969 Apollo 11 News Release" (PDF) (Press release). Cleveland, OH: Lewis Research Center. 69-36. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2025. Retrieved April 8, 2025.

- ^ Portree, David S. F. (September 2, 2013). "Project Olympus (1962)". Wired. Archived from the original on March 23, 2025. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood & Swenson 1979, Ch. 1.7: "Feasility Studies". pp. 16–21.

- ^ Preble, Christopher A. (2003). ""Who Ever Believed in the 'Missile Gap'?": John F. Kennedy and the Politics of National Security". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 33 (4): 813. doi:10.1046/j.0360-4918.2003.00085.x. JSTOR 27552538.

- ^ Beschloss 1997

- ^ Sidey 1963, pp. 117–118

- ^ Beschloss 1997, p. 55

- ^ 87th Congress 1961

- ^ Sidey 1963, p. 114

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (April 20, 1961). "Memorandum for Vice President". The White House (Memorandum). Boston, MA: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Launius, Roger D. (July 1994). "President John F. Kennedy Memo for Vice President, 20 April 1961" (PDF). Apollo: A Retrospective Analysis (PDF). Monographs in Aerospace History. Washington, D.C.: NASA. OCLC 31825096. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2013. Key Apollo Source Documents Archived November 8, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Johnson, Lyndon B. (April 28, 1961). "Memorandum for the President". Office of the Vice President (Memorandum). Boston, MA: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Launius, Roger D. (July 1994). "Lyndon B. Johnson, Vice President, Memo for the President, 'Evaluation of Space Program,' 28 April 1961" (PDF). Apollo: A Retrospective Analysis (PDF). Monographs in Aerospace History. Washington, D.C.: NASA. OCLC 31825096. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2013. Key Apollo Source Documents Archived November 8, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (May 25, 1961). Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs (Motion picture (excerpt)). Boston, MA: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Accession number: TNC:200; digital identifier: TNC-200-2. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Murray & Cox 1989, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Sietzen, Frank (October 2, 1997). "Soviets Planned to Accept JFK's Joint Lunar Mission Offer". SpaceDaily. SpaceCast News Service. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "Soyuz – Development of the Space Station; Apollo – Voyage to the Moon". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood & Swenson 1979, Ch. 2.5: "Contracting for the Command Module". pp. 41–44.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Allen, Bob (ed.). "NASA Langley Research Center's Contributions to the Apollo Program". Langley Research Center. NASA. Archived from the original on December 10, 2004. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "Historical Facts". MSFC History Office. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Swenson, Loyd S. Jr.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1989) [Originally published 1966]. "Chapter 12.3: Space Task Group Gets a New Home and Name". This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury. The NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA. OCLC 569889. NASA SP-4201. Archived from the original on July 13, 2009. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Dethloff, Henry C. (1993). "Chapter 3: Houston – Texas – U.S.A.". Suddenly Tomorrow Came ... A History of the Johnson Space Center. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. ISBN 978-1502753588.

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (September 12, 1962). "Address at Rice University on the Nation's Space Effort". Boston, MA: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on May 6, 2010. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Nixon, Richard M. (February 19, 1973). "50—Statement About Signing a Bill Designating the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, as the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center". The American Presidency Project. University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ "Dr. Kurt H. Debus". Kennedy Biographies. NASA. February 1987. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ "Executive Orders Disposition Tables: Lyndon B. Johnson – 1963: Executive Order 11129". Office of the Federal Register. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ The building was renamed "Vehicle Assembly Building" on February 3, 1965. "VAB Nears Completion". NASA History Program Office. NASA. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

The new name, it was felt, would more readily encompass future as well as current programs and would not be tied to the Saturn booster.

- ^ Craig, Kay (ed.). "KSC Technical Capabilities: O&C Altitude Chambers". Center Planning and Development Office. NASA. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2011.