Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

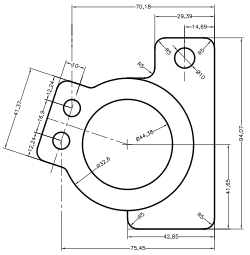

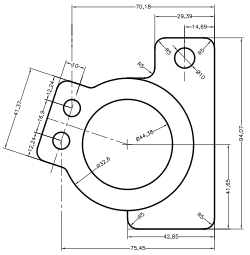

Structural drawing

View on Wikipedia| Part of series on |

| Technical drawings |

|---|

|

Structural drawings are commonly used across many branches of engineering and are illustrations depicting the specific design and layout of a building’s Structural elements. They provide a comprehensive overview of the building in its entirety and are key in an organized and accurate construction and design process.[1] They also provide a standardized approach to conveying this information and allowing for the design of all structures to be safe and accurate. Structural drawings differ from architectural design as they mainly focus on how the building can be made as strong and stable as possible and what materials will be needed for this task. Structural drawings are then used in collaboration with architectural, mechanical, engineering, and plumbing plans to construct the final product.[2]

History

[edit]

The earliest engineers, dating back to ancient civilizations, all relied on basic sketches and plans for their structures. As time and technology progressed with the Renaissance and Industrial Revolution, the conventions and symbols for drawing structures became uniform. Computer software has also been developed to help aid in precise designing.

Importance

[edit]Without structural plans, there would be no concrete proof that the building will meet all necessary regulations. Furthermore, these drawings serve as the blueprints that all parties involved in the building and design process will have to follow to some degree. This allows collaboration and communication between all the different disciplines to run efficiently. Without these drawings serving as a necessary blueprint, the project would become disconnected, and the potential for error would increase significantly. Structural drawings also allow for an accurate gauge of how much material will be needed and what that will subsequently cost. This estimate will help you define and stick to a budget for a more economical build. Finally, it is arguably most important that these structural drawings are clear and accurate. If your drawing leaves anything unspecified or unclear, this may lead to mistakes affecting the quality of the building.

Different aspects and how to read them

[edit]

Information Blocks contain necessary steps and information about the assembly and are located on the bottom right of the drawing. They also contain details such as who the drawing is for, what it is, numbered parts and a description of each, and useful information about the materials that are needed. The information blocks are composed of the following:[3]

A Title Block is found in the bottom right corner of the drawing and provides basic context to what is being depicted. It will contain details such as company name and address, part numbers, scale, mass, material, units, and drawing off status.[4]

A Revision Block can be found in the upper right corner and details changes and revisions made to the drawing, the date of revisions, and if they were approved.[5]

The Bill of Materials (BOM) Block is either just above the title or in the upper-left corner and lists all the items needed to build the structure and how much of each item is necessary.[6]

There are also a few different line types that are used in the drawings. A visible line indicates an edge that can be seen. A hidden line shows a line that cannot be seen. A phantom line shows the path of movement of a moving part. Finally, Centre lines show the center of the structure.[7]

General notes to give further instruction, material specifications, specific scales and dimensions, and standard symbols and abbreviations are also included in the structure drawing to ensure uniformity and accuracy.[8]

Types of structural drawings

[edit]

While more foundational plans may just detail the base and foundation of a structure, there are also framing plans and column and beam layouts.[9] This will show where specific joints, supports, columns, and beams need to be placed in order to secure the framework of the structure. For example, if you are designing a roof, a roof framing plan may detail the trusses and rafters necessary to support a specific roof load. There are also different structural drawings used to view the design from different angles such as cross-sectional drawings, elevations, and vertical sections.[10] If you are designing a structure using concrete, you may need to reinforce it with steel, as concrete will crack under tension. You may also just be using a steel frame somewhere in the design already. Either way, you may also need a structural drawing to show where and how the steel is connected and how it is spaced within the concrete.

Review

[edit]Once drawn, the design is then thoroughly peer evaluated and reviewed to ensure everything not only makes sense for a well-built structure, but to also ensure that everything is in line with regulatory building codes and standards. The drawing is also checked for any discrepancies or missed details and calculations that could lead to errors and confusion when building. From there, necessary revisions and adjustments are made.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ https://www.rib-software.com/en/blogs/structural-drawings-plans

- ^ https://www.rib-software.com/en/blogs/structural-drawings-plans

- ^ https://www.makeuk.org/insights/blogs/how-to-read-engineering-drawings-a-simple-guide

- ^ https://www.makeuk.org/insights/blogs/how-to-read-engineering-drawings-a-simple-guide

- ^ https://www.makeuk.org/insights/blogs/how-to-read-engineering-drawings-a-simple-guide

- ^ https://www.makeuk.org/insights/blogs/how-to-read-engineering-drawings-a-simple-guide

- ^ https://www.makeuk.org/insights/blogs/how-to-read-engineering-drawings-a-simple-guide

- ^ https://www.kreo.net/news-2d-takeoff/a-guide-to-structural-drawings

- ^ https://www.kreo.net/news-2d-takeoff/a-guide-to-structural-drawings

- ^ https://www.kreo.net/news-2d-takeoff/a-guide-to-structural-drawings

- https://www.kreo.net/news-2d-takeoff/a-guide-to-structural-drawings

- https://www.rib-software.com/en/blogs/structural-drawings-plans

- https://www.makeuk.org/insights/blogs/how-to-read-engineering-drawings-a-simple-guide