Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

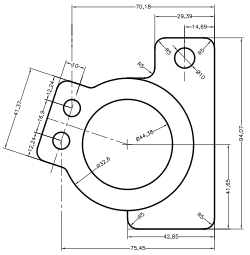

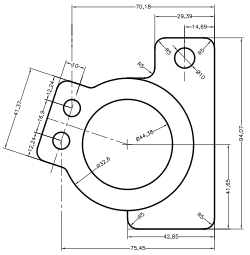

Blueprint

View on Wikipedia

| Part of series on |

| Technical drawings |

|---|

|

A blueprint is a reproduction of a technical drawing or engineering drawing using a contact print process on light-sensitive sheets introduced by Sir John Herschel in 1842.[1] The traditional white-on-blue appearance of blueprints is a result of the cyanotype process, which allowed rapid and accurate production of an unlimited number of copies of an original reference. It was widely used for over a century for the reproduction of specification drawings used in construction and industry. Blueprints were characterized by white lines on a blue background, a negative of the original. Color or shades of grey could not be reproduced.

The process is obsolete, initially superseded by the diazo-based whiteprint process, and later by large-format xerographic photocopiers. It has since almost entirely been superseded by digital computer-aided construction drawings.

The term blueprint continues to be used informally to refer to any floor plan[2] (and by analogy, any type of plan).[3][4] Practising engineers, architects, and drafters often call them drawings, prints, or plans.[5]

The blueprint process

[edit]

The blueprint process is based on a photosensitive ferric compound. The best known is a process using ammonium ferric citrate and potassium ferricyanide.[6][7] The paper is impregnated with a solution of ammonium ferric citrate and dried. When the paper is illuminated, a photoreaction turns the trivalent ferric iron into divalent ferrous iron. The image is then developed using a solution of potassium ferricyanide forming insoluble ferroferricyanide (Prussian blue or Turnbull's blue) with the divalent iron. Excess ammonium ferric citrate and potassium ferricyanide are then washed away.[8] The process is also known as cyanotype.

This is a simple process for the reproduction of any light transmitting document. Engineers and architects drew their designs on cartridge paper; these were then traced on to tracing paper using India ink for reproduction whenever needed. The tracing paper drawing is placed on top of the sensitized paper, and both are clamped under glass, in a daylight exposure frame, which is similar to a picture frame. The frame is put out into daylight, requiring a minute or two under a bright sun, or about thirty minutes under an overcast sky to complete the exposure. Where ultra-violet light is transmitted through the tracing paper, the light-sensitive coating converts to a stable blue or black dye. Where the India ink blocks the ultra-violet light the coating does not convert and remains soluble. The image can be seen forming. When a strong image is seen the frame is brought indoors to stop the process. The unconverted coating is washed away, and the paper is then dried. The result is a copy of the original image with the clear background area rendered dark blue and the image reproduced as a white line.

This process has several features:[9]

- the image is stable

- as it is a contact process, no large-field optical system is required

- the reproduced document will have the same scale as the original

- the paper is soaked in liquid during processing, and minor distortions can occur

- the dark blue background makes it difficult to alter, thus preserving

- the approved drawing during use

- a record of the approved specifications

- the history of alterations recorded on the sheet

- the references to other drawings

Introduction of the blueprint process eliminated the expense of photolithographic reproduction or of hand-tracing of original drawings. By the later 1890s in American architectural offices, a blueprint was one-tenth the cost of a hand-traced reproduction.[10] The blueprint process is still used for special artistic and photographic effects, on paper and fabrics.[11][self-published source?]

Various base materials have been used for blueprints. Paper was a common choice; for more durable prints linen was sometimes used, but with time, the linen prints would shrink slightly. To combat this problem, printing on imitation vellum and, later, polyester film (Mylar) was implemented.

Whiteprints

[edit]

Traditional blueprints became obsolete when less expensive printing methods and digital displays became available.

In the early 1940s, cyanotype blueprint began to be supplanted by diazo prints, also known as whiteprints. This technique produces blue lines on a white background. The drawings are also called blue-lines or bluelines.[12][13] Other comparable dye-based prints were known as blacklines. Diazo prints remained in use until they were replaced by xerographic print processes.

Xerography is standard copy machine technology using toner on copy paper. When large size xerography machines became available, c. 1975, they replaced the older printing methods. As computer-aided design techniques came into use, the designs were printed directly using a computer printer or plotter.

Digital

[edit]In most computer-aided design of parts to be machined, paper is avoided altogether, and the finished design is an image on the computer display. The computer-aided design program generates a computer numerical control sequence from the approved design. The sequence is a computer file which will control the operation of the machine tools used to make the part.

In the case of construction plans, such as road work or erecting a building, the supervising workers may view the "blueprints" directly on displays, rather than using printed paper sheets. These displays include mobile devices, such as smartphones or tablets.[14] Software allows users to view and annotate electronic drawing files. Construction crews use software in the field to edit, share, and view blueprint documents in real-time.[15]

Many of the original paper blueprints are archived since they are still in use. In many situations their conversion to digital form is prohibitively expensive. Most buildings and roads constructed before c. 1990 will only have paper blueprints, not digital. These originals have significant importance to the repair and alteration of constructions still in use, e.g. bridges, buildings, sewer systems, roads, railroads, etc., and sometimes in legal matters concerning the determination of, for example, property boundaries, or who owns or is responsible for a boundary wall.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Go., F. E. (1970). "Blueprint". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (Expo'70 ed.). Chicago: William Benton, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. p. 816. ISBN 0-85229-135-3.

- ^ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th ed.), Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2

- ^ "Blueprint". Dictionary.com. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Blueprint". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ C. Brown, Walter; K. Brown, Ryan (2011). Print Reading for Industry, 10th edition. The Goodheart-Wilcox Company, Inc. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-63126-051-3.

- ^ Blue, WS: PSLC.

- ^ C. Brown, Walter; K. Brown, Ryan (2011). Print Reading for Industry, 10th edition. The Goodheart-Wilcox Company, Inc. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-63126-051-3.

- ^ Bridgwater, William; Sherwood, Elizabeth J., eds. (1950). "blueprint". The Columbia Encyclopedia in One Volume (hardbound) (Second ed.). Morningside Heights, New York City: Columbia University Press. p. 214.

- ^ Ralph W. Liebing Architectural Working Drawings, John Wiley & Sons, 1999 ISBN 0471348767 page 576

- ^ Mary N. Woods From Craft to Profession: The Practice of Architecture in Nineteenth-Century America University of California Press, 1999 ISBN 0520214943, pages 239–240

- ^ Gary Fabbri, Malin Fabbri Blueprint to Cyanotypes – Exploring a Historical Alternative Photographic Process Lulu.com, 2006 ISBN 141169838X page 7[self-published source]

- ^ Pai, Damodar M.; Melnyk, Andrew R.; Weiss, David S.; Hann, Richard; Crooks, Walter; Pennington, Keith S.; Lee, Francis C.; Jaeger, C. Wayne; Titterington, Don R.; Lutz, Walter; Bräuninger, Arno; De Brabandere, Luc; Claes, Frans; De Keyzer, Rene; Janssens, Wilhelmus; Potts, Rod. "Imaging Technology, 2. Copying and Nonimpact Printing Processes". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–53. doi:10.1002/14356007.o13_o08.pub2. ISBN 9783527306732.

- ^ "Blueprints replaced by whiteprints".

- ^ Singer, Michael. "Crain Construction grows its 80-year-old business with iOS, Android tablets". tabtimes.com. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ "Construction Blueprint App". HCSS. 15 December 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

Further reading

[edit] The dictionary definition of blueprint at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of blueprint at Wiktionary Media related to Blueprints at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Blueprints at Wikimedia Commons

- Page, Walter Hines; Page, Arthur Wilson (November 1915). "Man And His Machines: Electric Blue Printing Machine". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXXI: 113.