Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Subcloning

View on Wikipedia

In molecular biology, subcloning is a technique used to move a particular DNA sequence from a parent vector to a destination vector.

Subcloning is not to be confused with molecular cloning, a related technique.

Procedure

[edit]Restriction enzymes are used to excise the gene of interest (the insert) from the parent. The insert is purified in order to isolate it from other DNA molecules. A common purification method is gel isolation. The number of copies of the gene is then amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Simultaneously, the same restriction enzymes are used to digest (cut) the destination. The idea behind using the same restriction enzymes is to create complementary sticky ends, which will facilitate ligation later on. A phosphatase, commonly calf-intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIAP), is also added to prevent self-ligation of the destination vector. The digested destination vector is isolated/purified.

The insert and the destination vector are then mixed together with DNA ligase. A typical molar ratio of insert genes to destination vectors is 3:1;[1] by increasing the insert concentration, self-ligation is further decreased. After letting the reaction mixture sit for a set amount of time at a specific temperature (dependent upon the size of the strands being ligated; for more information see DNA ligase), the insert should become successfully incorporated into the destination plasmid.

Amplification of product plasmid

[edit]The plasmid is often transformed into a bacterium like E. coli. Ideally when the bacterium divides the plasmid should also be replicated. In the best case scenario, each bacterial cell should have several copies of the plasmid. After a good number of bacterial colonies have grown, they can be miniprepped to harvest the plasmid DNA.

Selection

[edit]In order to ensure growth of only transformed bacteria (which carry the desired plasmids to be harvested), a marker gene is used in the destination vector for selection. Typical marker genes are for antibiotic resistance or nutrient biosynthesis. So, for example, the "marker gene" could be for resistance to the antibiotic ampicillin. If the bacteria that were supposed to pick up the desired plasmid had picked up the desired gene then they would also contain the "marker gene". Now the bacteria that picked up the plasmid would be able to grow in ampicillin whereas the bacteria that did not pick up the desired plasmid would still be vulnerable to destruction by the ampicillin. Therefore, successfully transformed bacteria would be "selected."

Example case: bacterial plasmid subcloning

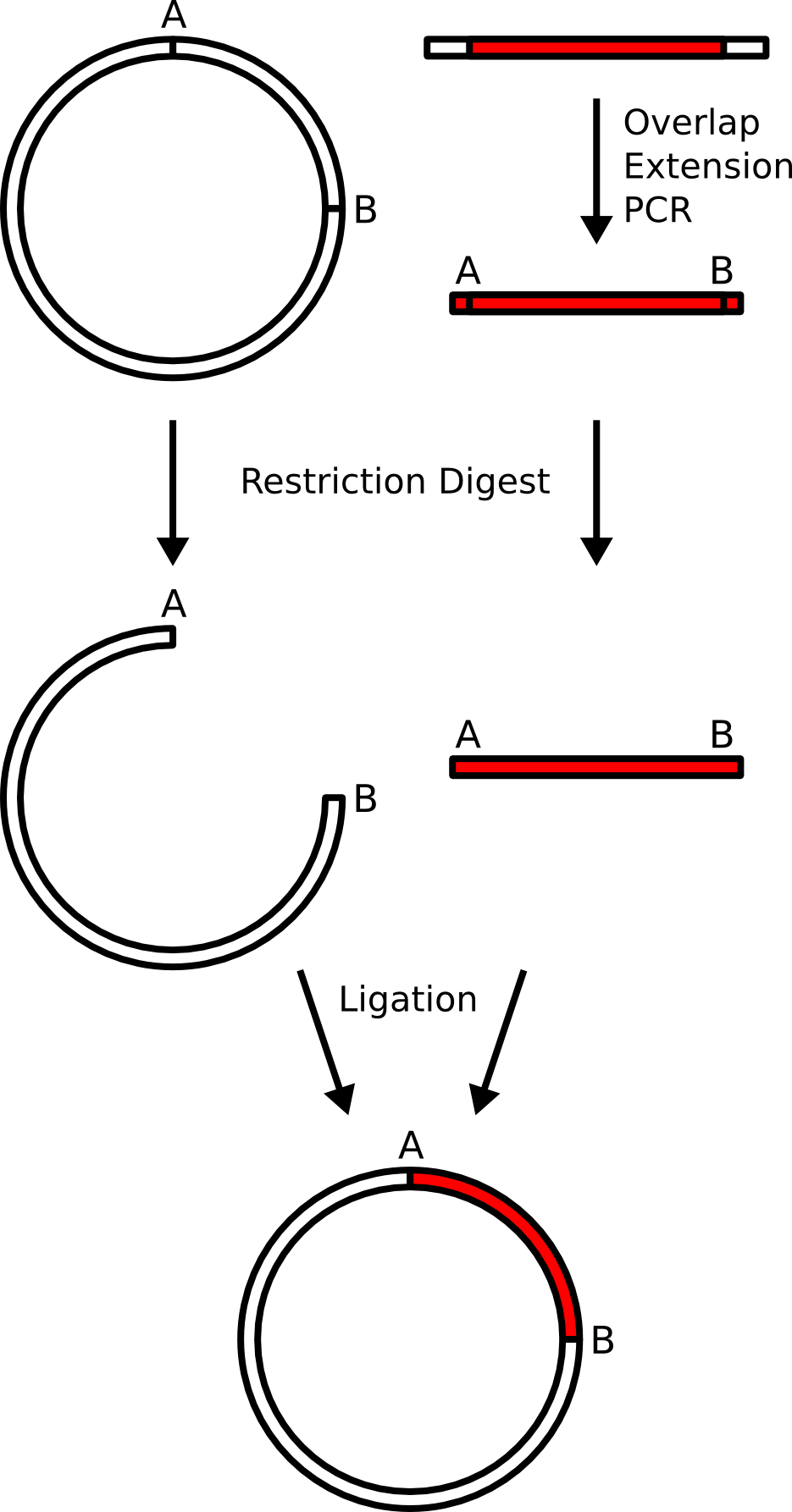

[edit]In this example, a gene from mammalian gene library will be subcloned into a bacterial plasmid (destination platform). The bacterial plasmid is a piece of circular DNA which contains regulatory elements allowing for the bacteria to produce a gene product (gene expression) if it is placed in the correct place in the plasmid. The production site is flanked by two restriction enzyme cutting sites "A" and "B" with incompatible sticky ends.

The mammalian DNA does not come with these restriction sites, so they are built in by overlap extension PCR. The primers are designed to put the restriction sites carefully, so that the coding of the protein is in-frame, and a minimum of extra amino acids is implanted on either side of the protein.

Both the PCR product containing the mammalian gene with the new restriction sites and the destination plasmid are subjected to restriction digestion, and the digest products are purified by gel electrophoresis.

The digest products, now containing compatible sticky ends with each other (but incompatible sticky ends with themselves) are subjected to ligation, creating a new plasmid which contains the background elements of the original plasmid with a different insert.

The plasmid is transformed into bacteria and the identity of the insert is confirmed by DNA sequencing.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Williams, Steven A.; et al. (2006). Laboratory Investigations in Molecular Biology. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 213. ISBN 9780763733292.