Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cloning

View on WikipediaIt has been suggested that this article be split out into a new article titled Cloning in fiction. (Discuss) (February 2025) |

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical genomes, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction; this reproduction of an organism by itself without a mate is known as parthenogenesis. In the field of biotechnology, cloning is the process of creating cloned organisms of cells and of DNA fragments.

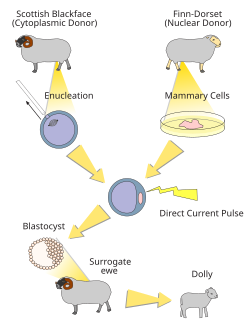

The artificial cloning of organisms, sometimes known as reproductive cloning, is often accomplished via somatic-cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), a cloning method in which a viable embryo is created from a somatic cell and an egg cell. In 1996, Dolly the sheep achieved notoriety for being the first mammal cloned from a somatic cell. Another example of artificial cloning is molecular cloning, a technique in molecular biology in which a single living cell is used to clone a large population of cells that contain identical DNA molecules.

In bioethics, there are a variety of ethical positions regarding the practice and possibilities of cloning. The use of embryonic stem cells, which can be produced through SCNT, in some stem cell research has attracted controversy. Cloning has been proposed as a means of reviving extinct species. In popular culture, the concept of cloning—particularly human cloning—is often depicted in science fiction; depictions commonly involve themes related to identity, the recreation of historical figures or extinct species, or cloning for exploitation (e.g. cloning soldiers for warfare).

Etymology

[edit]Coined by Herbert J. Webber in 1903, the term clone derives from the Ancient Greek word κλών (klōn), twig, which is the process whereby a new plant is created from a twig. In botany, the term lusus was used.[1] In horticulture, the spelling clon was used until the early twentieth century; the final e came into use to indicate the vowel is a "long o" instead of a "short o".[2][3] Since the term entered the popular lexicon in a more general context, the spelling clone has been used exclusively.

Natural cloning

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2022) |

Natural cloning is the production of clones without the involvement of genetic engineering techniques or human intervention (i.e. artificial cloning).[4] Natural cloning occurs through a variety of natural mechanisms, from single-celled organisms to complex multicellular organisms, and has allowed life forms to spread for hundreds of millions of years. Versions of this reproduction method are used by plants, fungi, and bacteria, and is also the way that clonal colonies reproduce themselves.[5][6] Some of the mechanisms are explored and used in plants and animals are binary fission, budding, fragmentation, and parthenogenesis.[7] It can also occur during some forms of asexual reproduction, when a single parent organism produces genetically identical offspring by itself.[8][9]

Many plants are well known for natural cloning ability, including blueberry plants, Hazel trees, the Pando trees,[10][11] the Kentucky coffeetree, Myrica, and the American sweetgum.

It also occurs accidentally in the case of identical twins, which are formed when a fertilized egg splits, creating two or more embryos that carry identical DNA.

Molecular cloning

[edit]Molecular cloning refers to the process of making multiple molecules. Cloning is commonly used to amplify DNA fragments containing whole genes, but it can also be used to amplify any DNA sequence such as promoters, non-coding sequences and randomly fragmented DNA. It is used in a wide array of biological experiments and practical applications ranging from genetic fingerprinting to large scale protein production. Occasionally, the term cloning is misleadingly used to refer to the identification of the chromosomal location of a gene associated with a particular phenotype of interest, such as in positional cloning. In practice, localization of the gene to a chromosome or genomic region does not necessarily enable one to isolate or amplify the relevant genomic sequence. To amplify any DNA sequence in a living organism, that sequence must be linked to an origin of replication, which is a sequence of DNA capable of directing the propagation of itself and any linked sequence. However, a number of other features are needed, and a variety of specialised cloning vectors (small piece of DNA into which a foreign DNA fragment can be inserted) exist that allow protein production, affinity tagging, single-stranded RNA or DNA production and a host of other molecular biology tools.

Cloning of any DNA fragment essentially involves four steps[12]

- fragmentation - breaking apart a strand of DNA

- ligation – gluing together pieces of DNA in a desired sequence

- transfection – inserting the newly formed pieces of DNA into cells

- screening/selection – selecting out the cells that were successfully transfected with the new DNA

Although these steps are invariable among cloning procedures a number of alternative routes can be selected; these are summarized as a cloning strategy.

Initially, the DNA of interest needs to be isolated to provide a DNA segment of suitable size. Subsequently, a ligation procedure is used where the amplified fragment is inserted into a vector (piece of DNA). The vector (which is frequently circular) is linearised using restriction enzymes, and incubated with the fragment of interest under appropriate conditions with an enzyme called DNA ligase. Following ligation, the vector with the insert of interest is transfected into cells. A number of alternative techniques are available, such as chemical sensitisation of cells, electroporation, optical injection and biolistics. Finally, the transfected cells are cultured. As the aforementioned procedures are of particularly low efficiency, there is a need to identify the cells that have been successfully transfected with the vector construct containing the desired insertion sequence in the required orientation. Modern cloning vectors include selectable antibiotic resistance markers, which allow only cells in which the vector has been transfected, to grow. Additionally, the cloning vectors may contain colour selection markers, which provide blue/white screening (alpha-factor complementation) on X-gal medium. Nevertheless, these selection steps do not absolutely guarantee that the DNA insert is present in the cells obtained. Further investigation of the resulting colonies must be required to confirm that cloning was successful. This may be accomplished by means of PCR, restriction fragment analysis and/or DNA sequencing.

Cell cloning

[edit]Cloning unicellular organisms

[edit]

Cloning a cell means to derive a population of cells from a single cell. In the case of unicellular organisms such as bacteria and yeast, this process is remarkably simple and essentially only requires the inoculation of the appropriate medium. However, in the case of cell cultures from multi-cellular organisms, cell cloning is an arduous task as these cells will not readily grow in standard media.

A useful tissue culture technique used to clone distinct lineages of cell lines involves the use of cloning rings (cylinders).[13] In this technique a single-cell suspension of cells that have been exposed to a mutagenic agent or drug used to drive selection is plated at high dilution to create isolated colonies, each arising from a single and potentially clonal distinct cell. At an early growth stage when colonies consist of only a few cells, sterile polystyrene rings (cloning rings), which have been dipped in grease, are placed over an individual colony and a small amount of trypsin is added. Cloned cells are collected from inside the ring and transferred to a new vessel for further growth.

Cloning stem cells

[edit]Somatic-cell nuclear transfer, popularly known as SCNT, can also be used to create embryos for research or therapeutic purposes. The most likely purpose for this is to produce embryos for use in stem cell research. This process is also called "research cloning" or "therapeutic cloning". The goal is not to create cloned human beings (called "reproductive cloning"), but rather to harvest stem cells that can be used to study human development and to potentially treat disease. While a clonal human blastocyst has been created, stem cell lines are yet to be isolated from a clonal source.[14]

Therapeutic cloning is achieved by creating embryonic stem cells in the hopes of treating diseases such as diabetes and Alzheimer's. The process begins by removing the nucleus (containing the DNA) from an egg cell and inserting a nucleus from the adult cell to be cloned.[15] In the case of someone with Alzheimer's disease, the nucleus from a skin cell of that patient is placed into an empty egg. The reprogrammed cell begins to develop into an embryo because the egg reacts with the transferred nucleus. The embryo will become genetically identical to the patient.[15] The embryo will then form a blastocyst which has the potential to form/become any cell in the body.[16]

The reason why SCNT is used for cloning is because somatic cells can be easily acquired and cultured in the lab. This process can either add or delete specific genomes of farm animals. A key point to remember is that cloning is achieved when the oocyte maintains its normal functions and instead of using sperm and egg genomes to replicate, the donor's somatic cell nucleus is inserted into the oocyte.[17] The oocyte will react to the somatic cell nucleus, the same way it would to a sperm cell's nucleus.[17]

The process of cloning a particular farm animal using SCNT is relatively the same for all animals. The first step is to collect the somatic cells from the animal that will be cloned. The somatic cells could be used immediately or stored in the laboratory for later use.[17] The hardest part of SCNT is removing maternal DNA from an oocyte at metaphase II. Once this has been done, the somatic nucleus can be inserted into an egg cytoplasm.[17] This creates a one-cell embryo. The grouped somatic cell and egg cytoplasm are then introduced to an electrical current.[17] This energy will hopefully allow the cloned embryo to begin development. The successfully developed embryos are then placed in surrogate recipients, such as a cow or sheep in the case of farm animals.[17]

SCNT is seen as a good method for producing agriculture animals for food consumption. It successfully cloned sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs. Another benefit is SCNT is seen as a solution to clone endangered species that are on the verge of going extinct.[17] However, stresses placed on both the egg cell and the introduced nucleus can be enormous, which led to a high loss in resulting cells in early research. For example, the cloned sheep Dolly was born after 277 eggs were used for SCNT, which created 29 viable embryos. Only three of these embryos survived until birth, and only one survived to adulthood.[18] As the procedure could not be automated, and had to be performed manually under a microscope, SCNT was very resource intensive. The biochemistry involved in reprogramming the differentiated somatic cell nucleus and activating the recipient egg was also far from being well understood. However, by 2014 researchers were reporting cloning success rates of seven to eight out of ten[19] and in 2016, a Korean Company Sooam Biotech was reported to be producing 500 cloned embryos per day.[20]

In SCNT, not all of the donor cell's genetic information is transferred, as the donor cell's mitochondria that contain their own mitochondrial DNA are left behind. The resulting hybrid cells retain those mitochondrial structures which originally belonged to the egg. As a consequence, clones such as Dolly that are born from SCNT are not perfect copies of the donor of the nucleus.

Organism cloning

[edit]Organism cloning (also called reproductive cloning) refers to the procedure of creating a new multicellular organism, genetically identical to another. In essence this form of cloning is an asexual method of reproduction, where fertilization or inter-gamete contact does not take place. Asexual reproduction is a naturally occurring phenomenon in many species, including most plants and some insects. Scientists have made some major achievements with cloning, including the asexual reproduction of sheep and cows. There is a lot of ethical debate over whether or not cloning should be used. However, cloning, or asexual propagation,[21] has been common practice in the horticultural world for hundreds of years.

Horticultural

[edit]

The term clone is used in horticulture to refer to descendants of a single plant which were produced by vegetative reproduction or apomixis. Many horticultural plant cultivars are clones, having been derived from a single individual, multiplied by some process other than sexual reproduction.[22] As an example, some European cultivars of grapes represent clones that have been propagated for over two millennia. Other examples are potatoes and bananas.[23]

Grafting can be regarded as cloning, since all the shoots and branches coming from the graft are genetically a clone of a single individual, but this particular kind of cloning has not come under ethical scrutiny and is generally treated as an entirely different kind of operation.

Many trees, shrubs, vines, ferns and other herbaceous perennials form clonal colonies naturally. Parts of an individual plant may become detached by fragmentation and grow on to become separate clonal individuals. A common example is in the vegetative reproduction of moss and liverwort gametophyte clones by means of gemmae. Some vascular plants e.g. dandelion and certain viviparous grasses also form seeds asexually, termed apomixis, resulting in clonal populations of genetically identical individuals.

Parthenogenesis

[edit]Clonal derivation exists in nature in some animal species and is referred to as parthenogenesis (reproduction of an organism by itself without a mate). This is an asexual form of reproduction that is only found in females of some insects, crustaceans, nematodes,[24] fish (for example the hammerhead shark[25]), Cape honeybees,[26] and lizards including the Komodo dragon[25] and several whiptails. The growth and development occurs without fertilization by a male. In plants, parthenogenesis means the development of an embryo from an unfertilized egg cell, and is a component process of apomixis. In species that use the XY sex-determination system, the offspring will always be female. An example of partenogenesis is the little fire ant (Wasmannia auropunctata), which is native to Central and South America but has spread throughout many tropical environments.

Artificial cloning of organisms

[edit]Artificial cloning of organisms may also be called reproductive cloning.

First steps

[edit]Hans Spemann, a German embryologist was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1935 for his discovery of the effect now known as embryonic induction, exercised by various parts of the embryo, that directs the development of groups of cells into particular tissues and organs. In 1924 he and his student, Hilde Mangold, were the first to perform somatic-cell nuclear transfer using amphibian embryos – one of the first steps towards cloning.[27]

Methods

[edit]Reproductive cloning generally uses "somatic cell nuclear transfer" (SCNT) to create animals that are genetically identical. This process entails the transfer of a nucleus from a donor adult cell (somatic cell) to an egg from which the nucleus has been removed, or to a cell from a blastocyst from which the nucleus has been removed.[28] If the egg begins to divide normally it is transferred into the uterus of the surrogate mother. Such clones are not strictly identical since the somatic cells may contain mutations in their nuclear DNA. Additionally, the mitochondria in the cytoplasm also contains DNA and during SCNT this mitochondrial DNA is wholly from the cytoplasmic donor's egg, thus the mitochondrial genome is not the same as that of the nucleus donor cell from which it was produced. This may have important implications for cross-species nuclear transfer in which nuclear-mitochondrial incompatibilities may lead to death.

Artificial embryo splitting or embryo twinning, a technique that creates monozygotic twins from a single embryo, is not considered in the same fashion as other methods of cloning. During that procedure, a donor embryo is split in two distinct embryos, that can then be transferred via embryo transfer. It is optimally performed at the 6- to 8-cell stage, where it can be used as an expansion of IVF to increase the number of available embryos.[29] If both embryos are successful, it gives rise to monozygotic (identical) twins.

Dolly the sheep

[edit]

Dolly, a Finn-Dorset ewe, was the first mammal to have been successfully cloned from an adult somatic cell. Dolly was formed by taking a cell from the udder of her 6-year-old biological mother.[30] Dolly's embryo was created by taking the cell and inserting it into a sheep ovum. It took 435 attempts before an embryo was successful.[31] The embryo was then placed inside a female sheep that went through a normal pregnancy.[32] She was cloned at the Roslin Institute in Scotland by British scientists Sir Ian Wilmut and Keith Campbell and lived there from her birth in 1996 until her death in 2003 when she was six. She was born on 5 July 1996 but not announced to the world until 22 February 1997.[33] Her stuffed remains were placed at Edinburgh's Royal Museum, part of the National Museums of Scotland.[34]

Dolly was publicly significant because the effort showed that genetic material from a specific adult cell, designed to express only a distinct subset of its genes, can be redesigned to grow an entirely new organism. Before this demonstration, it had been shown by John Gurdon that nuclei from differentiated cells could give rise to an entire organism after transplantation into an enucleated egg.[35] However, this concept was not yet demonstrated in a mammalian system.

The first mammalian cloning (resulting in Dolly) had a success rate of 29 embryos per 277 fertilized eggs, which produced three lambs at birth, one of which lived. In a bovine experiment involving 70 cloned calves, one-third of the calves died quite young. The first successfully cloned horse, Prometea, took 814 attempts. Notably, although the first clones were frogs, no adult cloned frog has yet been produced from a somatic adult nucleus donor cell.[36]

There were early claims that Dolly had pathologies resembling accelerated aging. Scientists speculated that Dolly's death in 2003 was related to the shortening of telomeres, DNA-protein complexes that protect the end of linear chromosomes. However, other researchers, including Ian Wilmut who led the team that successfully cloned Dolly, argue that Dolly's early death due to respiratory infection was unrelated to problems with the cloning process. This idea that the nuclei have not irreversibly aged was shown in 2013 to be true for mice.[37]

Dolly was named after performer Dolly Parton because the cells cloned to make her were from a mammary gland cell, and Parton is known for her ample cleavage.[38]

Recent advances in biotechnology allowed the modification of wolf clones to make them appear similar to dire wolves by a company named Colossal Biosciences. "The company used a combination of gene-editing techniques and ancient DNA found in fossils to engineer the newborn pups."[39] It's currently contested whether this can be considered a true dire wolf[40], but this shows that gene modification and possibly cloning in the future could advance. They produced three of the white "dire wolves" and scientists are more interested in how this can be used for endangered animals.[citation needed]

Species cloned and applications

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2023) |

The modern cloning techniques involving nuclear transfer have been successfully performed on several species. Notable experiments include:

- Tadpole: (1952) Robert Briggs and Thomas J. King successfully cloned northern leopard frogs: thirty-five complete embryos and twenty-seven tadpoles from one-hundred and four successful nuclear transfers.[41][42]

- Carp: (1963) In China, embryologist Tong Dizhou produced the world's first cloned fish by inserting the DNA from a cell of a male carp into an egg from a female carp.[43]

- Zebrafish: (1981) George Streisinger produced the first cloned vertebrate.[44]

- Sheep: (1984) Steen Willadsen produced the first cloned mammal from early embryonic cells.

- In June 1995, the Roslin Institute cloned Megan and Morag from differentiated embryonic cells.[45][46]

- In July 1996, PPL Therapeutics and the Roslin Institute cloned Dolly the sheep from a somatic cell.[47][43]

- Mouse: (1986) A mouse was successfully cloned from an early embryonic cell. In 1987, Soviet scientists Levon Chaylakhyan, Veprencev, Sviridova, and Nikitin cloned Masha, a mouse.[clarification needed][48][49][needs update]

- Rhesus monkey: (October 1999) The Oregon National Primate Research Center cloned Tetra from embryo splitting and not nuclear transfer: a process more akin to artificial formation of twins.[50][51]

- Pig: (March 2000) PPL Therapeutics cloned five piglets.[52] By 2014, BGI in China was producing 500 cloned pigs a year to test new medicines.[53]

- Gaur: (2001) was the first endangered species cloned.[54]

- Cattle:

- Alpha and Beta (males, 2001) and (2005), Brazil[55]

- In 2023, Chinese scientists reported the cloning of three supercows with a milk productivity "nearly 1.7 times the amount of milk an average cow in the United States produced in 2021" and a plan for 1,000 of such super cows in the near-term. According to a news report "[i]n many countries, including the United States, farmers breed clones with conventional animals to add desirable traits, such as high milk production or disease resistance, into the gene pool".[clarification needed][when?][56]

- Cat: CopyCat "CC" (female, late 2001), Little Nicky, 2004, was the first cat cloned for commercial reasons[57]

- Rat: Ralph, the first cloned rat (2003)[58]

- Mule: Idaho Gem, a john mule born 4 May 2003, was the first horse-family clone.[59]

- Horse: Prometea, a Haflinger female born 28 May 2003, was the first horse clone.[60]

- Przewalksi's Horse: An ongoing cloning program by the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance and Revive & Restore attempts to reintroduce genetic diversity to this endangered species.[61]

- Dog:

- Snuppy, a male Afghan hound was the first cloned dog (2005).[64] In 2017, the world's first gene-editing clone dog, Apple, was created by Sinogene Biotechnology.[65] Sooam Biotech, South Korea, was reported in 2015 to have cloned 700 dogs to date for their owners, including two Yakutian Laika hunting dogs, which are seriously endangered due to crossbreeding.[66]

- Cloning of super sniffer dogs was reported in 2011, four years afterwards when the dogs started working.[67] Cloning of a successful rescue dog was also reported in 2009[68] and of a similar police dog in 2019.[69] Cancer-sniffing dogs have also been cloned. A review concluded that "qualified elite working dogs can be produced by cloning a working dog that exhibits both an appropriate temperament and good health."[70]

- Wolf: Snuwolf and Snuwolffy, the first two cloned female wolves (2005).[71]

- Water buffalo: Samrupa was the first cloned water buffalo. It was born on 6 February 2009, at India's Karnal National Dairy Research Institute but died five days later due to lung infection.[72]

- Pyrenean ibex: (2009) was the first extinct animal to be cloned back to life; the clone lived for seven minutes before dying of lung defects.[73] The extinct Pyrenean ibex is a sub-species of the extant Spanish ibex.[74]

- Camel: (2009) Injaz, was the first cloned camel.[75]

- Pashmina goat: (2012) Noori, is the first cloned pashmina goat. Scientists at the faculty of veterinary sciences and animal husbandry of Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir successfully cloned the first Pashmina goat (Noori) using the advanced reproductive techniques under the leadership of Riaz Ahmad Shah.[76]

- Goat: (2001) Scientists of Northwest A&F University successfully cloned the first goat which use the adult female cell.[77]

- Gastric brooding frog: (2013) The gastric brooding frog, Rheobatrachus silus, thought to have been extinct since 1983 was cloned in Australia, although the embryos died after a few days.[78]

- Macaque monkey: (2017) First successful cloning of a primate species using nuclear transfer, with the birth of two live clones named Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua. Conducted in China in 2017, and reported in January 2018.[79][80][81][82] In January 2019, scientists in China reported the creation of five identical cloned gene-edited monkeys, using the same cloning technique that was used with Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua and Dolly the sheep, and the gene-editing Crispr-Cas9 technique allegedly used by He Jiankui in creating the first ever gene-modified human babies Lulu and Nana. The monkey clones were made to study several medical diseases.[83][84]

- Black-footed ferret: (2020) A team of scientists cloned a female named Willa, who died in the mid-1980s and left no living descendants. Her clone, a female named Elizabeth Ann, was born on 10 December. Scientists hope that the contribution of this individual will alleviate the effects of inbreeding and help black-footed ferrets better cope with plague. Experts estimate that this female's genome contains three times as much genetic diversity as any of the modern black-footed ferrets.[85]

- First artificial parthenogenesis in mammals: (2022) Viable mice offspring was born from unfertilized eggs via targeted DNA methylation editing of seven imprinting control regions.[86]

Human cloning

[edit]Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of a human. The term is generally used to refer to artificial human cloning, which is the reproduction of human cells and tissues. It does not refer to the natural conception and delivery of identical twins. The possibility of human cloning has raised controversies. These ethical concerns have prompted several nations to pass legislation regarding human cloning and its legality. As of right now, scientists have no intention of trying to clone people and they believe their results should spark a wider discussion about the laws and regulations the world needs to regulate cloning.[87]

Two commonly discussed types of theoretical human cloning are therapeutic cloning and reproductive cloning. Therapeutic cloning would involve cloning cells from a human for use in medicine and transplants, and is an active area of research, but is not in medical practice anywhere in the world, as of 2024[update]. Two common methods of therapeutic cloning that are being researched are somatic-cell nuclear transfer and, more recently, pluripotent stem cell induction. Reproductive cloning would involve making an entire cloned human, instead of just specific cells or tissues.[88]

Ethical issues of cloning

[edit]There are a variety of ethical positions regarding the possibilities of cloning, especially human cloning. While many of these views are religious in origin, the questions raised by cloning are faced by secular perspectives as well. Perspectives on human cloning are theoretical, as human therapeutic and reproductive cloning are not commercially used; animals are currently cloned in laboratories and in livestock production.

Advocates support development of therapeutic cloning to generate tissues and whole organs to treat patients who otherwise cannot obtain transplants,[89] to avoid the need for immunosuppressive drugs,[88] and to stave off the effects of aging.[90] Advocates for reproductive cloning believe that parents who cannot otherwise procreate should have access to the technology.[91]

Opponents of cloning have concerns that technology is not yet developed enough to be safe[92] and that it could be prone to abuse (leading to the generation of humans from whom organs and tissues would be harvested),[93][94] as well as concerns about how cloned individuals could integrate with families and with society at large.[95][96] Cloning humans could lead to serious violations of human rights.[97]

Religious groups are divided, with some opposing the technology as usurping "God's place" and, to the extent embryos are used, destroying a human life; others support therapeutic cloning's potential life-saving benefits.[98][99] There is at least one religion, Raëlism, in which cloning plays a major role.[100][101][102]

Contemporary work on this topic is concerned with the ethics, adequate regulation and issues of any cloning carried out by humans, not potentially by extraterrestrials (including in the future), and largely also not replication – also described as mind cloning[103][104][105][106] – of potential whole brain emulations.

Cloning of animals is opposed by animal-groups due to the number of cloned animals that suffer from malformations before they die, and while food from cloned animals has been approved as safe by the US FDA,[107][108] its use is opposed by groups concerned about food safety.[109][110]

In practical terms, the inclusion of "licensing requirements for embryo research projects and fertility clinics, restrictions on the commodification of eggs and sperm, and measures to prevent proprietary interests from monopolizing access to stem cell lines" in international cloning regulations has been proposed, albeit e.g. effective oversight mechanisms or cloning requirements have not been described.[111]

Cloning extinct and endangered species

[edit]Cloning, or more precisely, the reconstruction of functional DNA from extinct species has, for decades, been a dream. Possible implications of this were dramatized in the 1984 novel Carnosaur and the 1990 novel Jurassic Park.[112][113] The best current cloning techniques have an average success rate of 9.4 percent[114] (and as high as 25 percent[37]) when working with familiar species such as mice,[note 1] while cloning wild animals is usually less than 1 percent successful.[117]

Conservation cloning

[edit]Several tissue banks have come into existence, including the "Frozen zoo" at the San Diego Zoo, to store frozen tissue from the world's rarest and most endangered species.[112][118][119][120] This is also referred to as "Conservation cloning".[121][122]

Engineers have proposed a "lunar ark" in 2021 – storing millions of seed, spore, sperm and egg samples from Earth's contemporary species in a network of lava tubes on the Moon as a genetic backup.[123][124][125] Similar proposals have been made since at least 2008.[126] These also include sending human customer DNA,[127] and a proposal for "a lunar backup record of humanity" that includes genetic information by Avi Loeb et al.[128]

In 2020, the San Diego Zoo began a number of projects in partnership with the conservation organization Revive & Restore and the ViaGen Pets and Equine Company to clone individuals of genetically-impoverished endangered species. A Przewalski's horse was cloned from preserved tissue of a stallion whose genes are absent in the surviving populations of the species, which descend from twenty individuals. The clone, named Kurt, had been born to a domestic surrogate mother, and was partnered with a natural-born Przewalski's mare in order to socialize him with the species' natural behavior before being introduced to the Zoo's breeding herd.[129] In 2023, a second clone of the original stallion, named Ollie, was born; this marked the first instance of multiple living clones of a single individual of an endangered species being alive at the same time.[130] Also in 2020, a clone named Elizabeth Ann was produced of a female black-footed ferret that had no living descendants.[131] While Elizabeth Ann became sterile due to secondary health complications, a pair of additional clones of the same individual, named Antonia and Noreen, were born to distinct surrogate mothers, and Antonia successfully reproduced later in the year.[132]

De-extinction

[edit]One of the most anticipated targets for cloning was once the woolly mammoth, but attempts to extract DNA from frozen mammoths have been unsuccessful, though a joint Russo-Japanese team is currently working toward this goal.[when?] In January 2011, it was reported by Yomiuri Shimbun that a team of scientists headed by Akira Iritani of Kyoto University had built upon research by Dr. Wakayama, saying that they will extract DNA from a mammoth carcass that had been preserved in a Russian laboratory and insert it into the egg cells of an Asian elephant in hopes of producing a mammoth embryo. The researchers said they hoped to produce a baby mammoth within six years.[133][134] The challenges are formidable. Extensively degraded DNA that may be suitable for sequencing may not be suitable for cloning; it would have to be synthetically reconstituted. In any case, with currently available technology, DNA alone is not suitable for mammalian cloning; intact viable cell nuclei are required. Patching pieces of reconstituted mammoth DNA into an Asian elephant cell nucleus would result in an elephant-mammoth hybrid rather than a true mammoth.[135] Moreover, true de-extinction of the wooly mammoth species would require a breeding population, which would require cloning of multiple genetically distinct but reproductively compatible individuals, multiplying both the amount of work and the uncertainties involved in the project. There are potentially other post-cloning problems associated with the survival of a reconstructed mammoth, such as the requirement of ruminants for specific symbiotic microbiota in their stomachs for digestion.[135]

Scientists at the University of Newcastle and University of New South Wales announced in March 2013 that the very recently extinct gastric-brooding frog would be the subject of a cloning attempt to resurrect the species.[136]

Many such "de-extinction" projects are being championed by the non-profit Revive & Restore.[137]

In 2022, scientists showed major limitations and the scale of challenge of genetic-editing-based de-extinction, suggesting resources spent on more comprehensive de-extinction projects such as of the woolly mammoth may currently not be well allocated and substantially limited. Their analyses "show that even when the extremely high-quality Norway brown rat (R. norvegicus) is used as a reference, nearly 5% of the genome sequence is unrecoverable, with 1,661 genes recovered at lower than 90% completeness, and 26 completely absent", complicated further by that "distribution of regions affected is not random, but for example, if 90% completeness is used as the cutoff, genes related to immune response and olfaction are excessively affected" due to which "a reconstructed Christmas Island rat would lack attributes likely critical to surviving in its natural or natural-like environment".[138]

In a 2021 online session of the Russian Geographical Society, Russia's defense minister Sergei Shoigu mentioned using the DNA of 3,000-year-old Scythian warriors to potentially bring them back to life. The idea was described as absurd at least at this point in news reports and it was noted that Scythians likely weren't skilled warriors by default.[139][140][141]

The idea of cloning Neanderthals or bringing them back to life in general is controversial but some scientists have stated that it may be possible in the future and have outlined several issues or problems with such as well as broad rationales for doing so.[142][143][144][145][146][147]

Unsuccessful attempts

[edit]In 2001, a cow named Bessie gave birth to a cloned Asian gaur, an endangered species, but the calf died after two days. In 2003, a banteng was successfully cloned, followed by three African wildcats from a thawed frozen embryo. These successes provided hope that similar techniques (using surrogate mothers of another species) might be used to clone extinct species. Anticipating this possibility, tissue samples from the last bucardo (Pyrenean ibex) were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after it died in 2000. Researchers are also considering cloning endangered species such as the Giant panda and Cheetah.[148][149][150][151]

In 2002, geneticists at the Australian Museum announced that they had replicated DNA of the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger), at the time extinct for about 65 years, using polymerase chain reaction.[152] However, on 15 February 2005 the museum announced that it was stopping the project after tests showed the specimens' DNA had been too badly degraded by the (ethanol) preservative. On 15 May 2005 it was announced that the thylacine project would be revived, with new participation from researchers in New South Wales and Victoria.[153]

In 2003, for the first time, an extinct animal, the Pyrenean ibex mentioned above was cloned, at the Centre of Food Technology and Research of Aragon, using the preserved frozen cell nucleus of the skin samples from 2001 and domestic goat egg-cells. The ibex died shortly after birth due to physical defects in its lungs.[154]

Lifespan

[edit]After an eight-year project involving the use of a pioneering cloning technique, Japanese researchers created 25 generations of healthy cloned mice with normal lifespans, demonstrating that clones are not intrinsically shorter-lived than naturally born animals.[37][155] Other sources have noted that the offspring of clones tend to be healthier than the original clones and indistinguishable from animals produced naturally.[156]

Some posited that Dolly the sheep may have aged more quickly than naturally born animals, as she died relatively early for a sheep at the age of six. Ultimately, her death was attributed to a respiratory illness, and the "advanced aging" theory is disputed.[157][dubious – discuss]

A 2016 study indicated that once cloned animals survive the first month or two of life they are generally healthy.[158] However, early pregnancy loss and neonatal losses are still greater with cloning than natural conception or assisted reproduction (IVF). Current research is attempting to overcome these problems.[38]

In popular culture

[edit]

Discussion of cloning in the popular media often presents the subject negatively. In an article in the 8 November 1993 article of Time, cloning was portrayed in a negative way, modifying Michelangelo's Creation of Adam to depict Adam with five identical hands.[159] Newsweek's 10 March 1997 issue also critiqued the ethics of human cloning, and included a graphic depicting identical babies in beakers.[160]

The concept of cloning, particularly human cloning, has featured a wide variety of science fiction works. An early fictional depiction of cloning is Bokanovsky's Process which features in Aldous Huxley's 1931 dystopian novel Brave New World. The process is applied to fertilized human eggs in vitro, causing them to split into identical genetic copies of the original.[161][162] Following renewed interest in cloning in the 1950s, the subject was explored further in works such as Poul Anderson's 1953 story UN-Man, which describes a technology called "exogenesis", and Gordon Rattray Taylor's book The Biological Time Bomb, which popularised the term "cloning" in 1963.[163]

Cloning is a recurring theme in a number of contemporary science fiction films, ranging from action films such as Anna to the Infinite Power, The Boys from Brazil, Jurassic Park (1993), Alien Resurrection (1997), The 6th Day (2000), Resident Evil (2002), Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones (2002), The Island (2005), Tales of the Abyss (2006), and Moon (2009) to comedies such as Woody Allen's 1973 film Sleeper.[164]

The process of cloning is represented variously in fiction. Many works depict the artificial creation of humans by a method of growing cells from a tissue or DNA sample; the replication may be instantaneous, or take place through slow growth of human embryos in artificial wombs. In the long-running British television series Doctor Who, the Fourth Doctor and his companion Leela were cloned in a matter of seconds from DNA samples ("The Invisible Enemy", 1977) and then – in an apparent homage to the 1966 film Fantastic Voyage – shrunk to microscopic size to enter the Doctor's body to combat an alien virus. The clones in this story are short-lived, and can only survive a matter of minutes before they expire.[165] Science fiction films such as The Matrix and Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones have featured scenes of human foetuses being cultured on an industrial scale in mechanical tanks.[166]

Cloning humans from body parts is also a common theme in science fiction. Cloning features strongly among the science fiction conventions parodied in Woody Allen's Sleeper, the plot of which centres around an attempt to clone an assassinated dictator from his disembodied nose.[167] In the 2008 Doctor Who story "Journey's End", a duplicate version of the Tenth Doctor spontaneously grows from his severed hand, which had been cut off in a sword fight during an earlier episode.[168]

After the death of her beloved 14-year-old Coton de Tulear named Samantha in late 2017, Barbra Streisand announced that she had cloned the dog, and was now "waiting for [the two cloned pups] to get older so [she] can see if they have [Samantha's] brown eyes and her seriousness".[169] The operation cost $50,000 through the pet cloning company ViaGen.[170]

In films such as Roger Spottiswoode's 2000 The 6th Day, which makes use of the trope of a "vast clandestine laboratory ... filled with row upon row of 'blank' human bodies kept floating in tanks of nutrient liquid or in suspended animation", clearly fear is to be incited. In Clark's view, the biotechnology is typically "given fantastic but visually arresting forms" while the science is either relegated to the background or fictionalised to suit a young audience.[171] Genetic engineering methods are weakly represented in film; Michael Clark, writing for The Wellcome Trust, calls the portrayal of genetic engineering and biotechnology "seriously distorted"[171]

Cloning and identity

[edit]Science fiction has used cloning, most commonly and specifically human cloning, to address questions of identity and eugenics.[172][173] A Number is a 2002 play by English playwright Caryl Churchill which addresses the subject of human cloning and identity, especially nature and nurture. The story, set in the near future, is structured around the conflict between a father (Salter) and his sons (Bernard 1, Bernard 2, and Michael Black) –the second two of whom are clones of the first. A Number was adapted by Caryl Churchill for television, in a co-production between the BBC and HBO Films.[174]

In 2012, a Japanese television series named "Bunshin" was created. The story's main character, Mariko, is a woman studying child welfare in Hokkaido. She grew up always doubtful about the love from her mother, who looked nothing like her and who died nine years before. One day, she finds some of her mother's belongings at a relative's house, and heads to Tokyo to seek out the truth behind her birth. She later discovered that she was a clone.[175]

In the 2013 television series Orphan Black, cloning is used as a scientific study on the behavioral adaptation of the clones.[176] In a similar vein, the book The Double by Nobel Prize winner José Saramago explores the emotional experience of a man who discovers that he is a clone.[177]

Cloning as resurrection

[edit]Cloning has been used in fiction as a way of recreating historical figures. In the 1976 Ira Levin novel The Boys from Brazil and its 1978 film adaptation, Josef Mengele uses cloning to create copies of Adolf Hitler.[178]

The Norman Spinrad's satirical The Iron Dream, published in 1972, concludes with 300 seven-foot-tall, blond, super-intelligent all-male SS clones in suspended animation launched into space to begin the Hitler analog's galactic empire in the aftermath of a genocidal race war. (They had won a Pyrrhic victory, the subhumans' leader having as his last act detonated a doomsday weapon, specifically a cobalt bomb, irredeemably contaminated the gene pool).[179]

In Michael Crichton's 1990 novel Jurassic Park, which spawned a series of Jurassic Park feature films, the bioengineering company InGen develops a technique to resurrect extinct species of dinosaurs by creating cloned creatures using DNA extracted from fossils. The cloned dinosaurs are used to populate the Jurassic Park wildlife park for the entertainment of visitors. The scheme goes disastrously wrong when the dinosaurs escape their enclosures.[180]

Cloning for warfare

[edit]The use of cloning for military purposes has also been explored in several fictional works. In Doctor Who, an alien race of armour-clad, warlike beings called Sontarans was introduced in the 1973 serial "The Time Warrior". Sontarans are depicted as squat, bald creatures who have been genetically engineered for combat. Their weak spot is a "probic vent", a small socket at the back of their neck which is associated with the cloning process.[181] The concept of cloned soldiers being bred for combat was revisited in "The Doctor's Daughter" (2008), when the Doctor's DNA is used to create a female warrior called Jenny.[182]

The 1977 film Star Wars was set against the backdrop of a historical conflict called the Clone Wars. The events of this war were not fully explored until the prequel films Attack of the Clones (2002) and Revenge of the Sith (2005), which depict a space war waged by a massive army of heavily armoured clone troopers that leads to the foundation of the Galactic Empire. Cloned soldiers are "manufactured" on an industrial scale, genetically conditioned for obedience and combat effectiveness. It is also revealed that the popular character Boba Fett originated as a clone of Jango Fett, a mercenary who served as the genetic template for the clone troopers.[183][184]

Cloning for exploitation

[edit]A recurring sub-theme of cloning fiction is the use of clones as a supply of organs for transplantation. The 2005 Kazuo Ishiguro novel Never Let Me Go and the 2010 film adaption[185] are set in an alternate history in which cloned humans are created for the sole purpose of providing organ donations to naturally born humans, despite the fact that they are fully sentient and self-aware. The 2005 film The Island[186] revolves around a similar plot, with the exception that the clones are unaware of the reason for their existence.

The exploitation of human clones for dangerous and undesirable work was examined in the 2009 British science fiction film Moon.[187] In the futuristic novel Cloud Atlas and subsequent film, one of the story lines focuses on a genetically engineered fabricant clone named Sonmi~451, one of millions raised in an artificial "wombtank", destined to serve from birth. She is one of thousands created for manual and emotional labor; Sonmi herself works as a server in a restaurant. She later discovers that the sole source of food for clones, called 'Soap', is manufactured from the clones themselves.[188]

In the film Us, at some point prior to the 1980s, the US Government creates clones of every citizen of the United States with the intention of using them to control their original counterparts, akin to voodoo dolls. This fails, as they were able to copy bodies, but unable to copy the souls of those they cloned. The project is abandoned and the clones are trapped exactly mirroring their above-ground counterparts' actions for generations. In the present day, the clones launch a surprise attack and manage to complete a mass-genocide of their unaware counterparts.[189][190]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ de Candolle, A. (1868). Laws of Botanical Nomenclature adopted by the International Botanical Congress held at Paris in August 1867; together with an Historical Introduction and Commentary by Alphonse de Candolle, Translated from the French. translated by H.A. Weddell. London: L. Reeve and Co.: 21, 43

- ^ "Torrey Botanical Club: Volumes 42–45". Torreya. 42–45: 133. 1942.

- ^ Herbert J. Webber (1903). Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. pp. 502–503. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ^ "Natural Cloning: Definition & Examples | StudySmarter". StudySmarter US. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Tasmanian bush could be oldest living organism". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 23 July 2006. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- ^ "Ibiza's Monster Marine Plant". Ibiza Spotlight. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- ^ "Natural Cloning: Definition & Examples | StudySmarter".

- ^ "Cloning Fact Sheet". Genome.gov. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Cloning | Definition, Process, & Types | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ DeWoody, J.; Rowe, C.A.; Hipkins, V.D.; Mock, K.E. (2008). ""Pando" Lives: Molecular Genetic Evidence of a Giant Aspen Clone in Central Utah". Western North American Naturalist. 68 (4): 493–497. Bibcode:2008WNAN...68..493D. doi:10.3398/1527-0904-68.4.493. ISSN 1944-8341. S2CID 59135424.

- ^ Mock, K.E.; Rowe, C.A.; Hooten, M.B.; Dewoody, J.; Hipkins, V.D. (2008). "Blackwell Publishing Ltd Clonal dynamics in western North American aspen (Populus tremuloides)". U.S. Department of Agriculture, Oxford, UK : Blackwell Publishing Ltd. p. 17. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Peter J. Russel (2005). iGenetics: A Molecular Approach. San Francisco, California, United States of America: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-8053-4665-7.

- ^ McFarland, Douglas (2000). "Preparation of pure cell cultures by cloning". Methods in Cell Science. 22 (1): 63–66. doi:10.1023/A:1009838416621. PMID 10650336.

- ^ Gil, Gideon (17 January 2008). "California biotech says it cloned a human embryo, but no stem cells produced". Boston Globe.

- ^ a b Halim, N. (September 2002). "Extensive new study shows abnormalities in cloned animals". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Plus, M. (2011). "Fetal development". Nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Latham, K. E. (2005). "Early and delayed aspects of nuclear reprogramming during cloning" (PDF). Biology of the Cell. pp. 97, 119–132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2014.

- ^ Campbell KH, McWhir J, Ritchie WA, Wilmut I (March 1996). "Sheep cloned by nuclear transfer from a cultured cell line". Nature. 380 (6569): 64–6. Bibcode:1996Natur.380...64C. doi:10.1038/380064a0. PMID 8598906. S2CID 3529638.

- ^ Shukman, David (14 January 2014) China cloning on an 'industrial scale' BBC News Science and Environment, Retrieved 10 April 2014

- ^ Zastrow, Mark (8 February 2016). "Inside the cloning factory that creates 500 new animals a day". New Scientist. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Asexual Propagation". Aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Sagers, Larry A. (2 March 2009) Proliferate favorite trees by grafting, cloning Archived 1 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine Utah State University, Deseret News (Salt Lake City) Retrieved 21 February 2014

- ^ Perrier, X.; De Langhe, E.; Donohue, M.; Lentfer, C.; Vrydaghs, L.; Bakry, F.; Carreel, F.; Hippolyte, I.; Horry, J. -P.; Jenny, C.; Lebot, V.; Risterucci, A. -M.; Tomekpe, K.; Doutrelepont, H.; Ball, T.; Manwaring, J.; De Maret, P.; Denham, T. (2011). "Multidisciplinary perspectives on banana (Musa spp.) domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (28): 11311–11318. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10811311P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1102001108. PMC 3136277. PMID 21730145.

- ^ Castagnone-Sereno P, et al. Diversity and evolution of root-knot nematodes, genus Meloidogyne: new insights from the genomic era Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2013;51:203-20

- ^ a b Shubin, Neil (24 February 2008). "Birds Do It. Bees Do It. Dragons Don't Need To". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 February 2014

- ^ Oldroyd, Benjamin P.; Yagound, Boris; Allsopp, Michael H.; Holmes, Michael J.; Buchmann, Gabrielle; Zayed, Amro; Beekman, Madeleine (9 June 2021). "Adaptive, caste-specific changes to recombination rates in a thelytokous honeybee population". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 288 (1952) 20210729. doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.0729. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 8187994. PMID 34102886. S2CID 235372422.

- News article about the study: "A single honeybee has cloned itself hundreds of millions of times". New Scientist. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ De Robertis, EM (April 2006). "Spemann's organizer and self-regulation in amphibian embryos". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 7 (4): 296–302. doi:10.1038/nrm1855. PMC 2464568. PMID 16482093.. See Box 1: Explanation of the Spemann-Mangold experiment

- ^ "Cloning Fact Sheet". Human Genome Project Information. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Illmensee K, Levanduski M, Vidali A, Husami N, Goudas VT (February 2009). "Human embryo twinning with applications in reproductive medicine". Fertil. Steril. 93 (2): 423–7. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.098. PMID 19217091.

- ^ Rantala, M.; Milgram, Arthur (1999). Cloning: For and Against. Chicago, Illinois: Carus Publishing Company. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8126-9375-1.

- ^ Swedin, Eric. "Cloning". CredoReference. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ Lassen, J.; Gjerris, M.; Sandøe, P. (2005). "After Dolly—Ethical limits to the use of biotechnology on farm animals" (PDF). Theriogenology. 65 (5): 992–1004. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.09.012. PMID 16253321. S2CID 10466667. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Swedin, Eric. "Cloning". CredoReference. Science in the Contemporary World. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ TV documentary Visions of the Future part 2 shows this process, explores the social implicatins of cloning and contains footage of monoculture in livestock

- ^ Gurdon J (April 1962). "Adult frogs derived from the nuclei of single somatic cells". Developmental Biology. 4 (2): 256–73. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(62)90043-x. PMID 13903027.

- ^ this is a source that was used in List of animals that have been cloned

- ^ a b c Wakayama S, Kohda T, Obokata H, Tokoro M, Li C, Terashita Y, Mizutani E, Nguyen VT, Kishigami S, Ishino F, Wakayama T (7 March 2013). "Successful serial recloning in the mouse over multiple generations". Cell Stem Cell. 12 (3): 293–7. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.005. PMID 23472871.

- ^ a b BBC. 22 February 2008. BBC On This Day: 1997: Dolly the sheep is cloned

- ^ Stening, Tanner (8 April 2025). "Did scientists genetically engineer the long-extinct dire wolf, or give gray wolf offspring its features?". Northeastern Global News. Retrieved 5 June 2025.

- ^ Mullin, Emily; Reynolds, Matt (7 April 2025). "Scientists Claim to Have Brought Back the Dire Wolf". Wired. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "ThinkQuest". Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Robert W. Briggs". National Academies Press. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Bloodlines timeline". PBS.

- ^ Streisinger, George; Walker, C.; Dower, N.; Knauber, D.; Singer, F. (1981), "Production of clones of homozygous diploid zebra fish (Brachydanio rerio)", Nature, 291 (5813): 293–296, Bibcode:1981Natur.291..293S, doi:10.1038/291293a0, PMID 7248006, S2CID 4323945

- ^ Campbell, K. H. S.; McWhir, J.; Ritchie, W. A.; Wilmut, I. (7 March 1996). "Sheep cloned by nuclear transfer from a cultured cell line". Nature. 380 (6569): 64–66. Bibcode:1996Natur.380...64C. doi:10.1038/380064a0. PMID 8598906. S2CID 3529638.

- ^ "Gene Genie". BBC World Service. 1 May 2000. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ McLaren A (2000). "Cloning: pathways to a pluripotent future". Science. 288 (5472): 1775–80. doi:10.1126/science.288.5472.1775. PMID 10877698. S2CID 44320353.

- ^ Chaylakhyan, Levon (1987). "Электростимулируемое слияние клеток в клеточной инженерии". Биофизика (in Russian). 32 (5): 874–887. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016.

- ^ "Кто изобрел клонирование?". Archived from the original on 23 December 2004. (Russian)

- ^ "Researchers clone monkey by splitting embryo". CNN. 13 January 2000. Archived from the original on 13 August 2006. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ Dean Irvine (19 November 2007). "You, again: Are we getting closer to cloning humans?". CNN. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Grisham, Julie (April 2000). "Pigs cloned for first time". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (4): 365. doi:10.1038/74335. PMID 10748477. S2CID 34996647.

- ^ Shukman, David (14 January 2014) China cloning on an 'industrial scale' BBC News Science and Environment, Retrieved 14 January 2014

- ^ Tobin, Kate (12 January 2001). "First cloned endangered species dies 2 days after birth". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Camacho, Keite (20 May 2005). "Embrapa clona raça de boi ameaçada de extinção". Agência Brasil (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ Gan, Nectar (2 February 2023). "China says it successfully cloned 3 highly productive 'super cows'". CNN Business. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "Americas | Pet kitten cloned for Christmas". BBC News. 23 December 2004. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "Rat called Ralph is latest clone". BBC News. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "Gordon Woods dies at 57; Veterinary scientist helped create first cloned mule". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 25 August 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "World's first cloned horse is born – 06 August 2003". New Scientist. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "Przewalski's Horse Project - Revive & Restore". Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Major Kurt Milestones - Revive & Restore". Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Tuff, Kika. "Przewalski's Foal Offers Further Hope for Conservation Cloning". Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "First Dog Clone". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 14 August 2005. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Wang, Serenitie; Rivers, Matt; Wang, Shunhe (27 December 2017). "Chinese firm clones gene-edited dog in bid to treat cardiovascular disease". CNN. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Bender, Kelli (27 June 2017). "You Look Familiar! Cloned Puppy Meets Her 'Mom' For the First Time". People. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Webster, George; Anderson, Becky (30 September 2011). "'Super clone' sniffer dogs: Coming to an airport near you?". CNN Business. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (18 June 2009). "Dog hailed as hero cloned by California company". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "China's first cloned police dog reports for duty". South China Morning Post. 19 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Kim, Min Jung; Oh, Hyun Ju; Hwang, Sun Young; Hur, Tai Young; Lee, Byeong Chun (1 September 2018). "Health and temperaments of cloned working dogs". Journal of Veterinary Science. 19 (5): 585–591. doi:10.4142/jvs.2018.19.5.585. ISSN 1229-845X. PMC 6167335. PMID 29929355. S2CID 49344658.

- ^ (1 September 2009) World's first cloned wolf dies Phys.Org, Retrieved 9 April 2015

- ^ Sinha, Kounteya (13 February 2009). "India clones world's first buffalo". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "Extinct ibex is resurrected by cloning". The Daily Telegraph. 31 January 2009. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009.

- ^ Maas, Peter H. J. (15 April 2012). "Pyrenean Ibex – Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica". The Sixth Extinction. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012.

- ^ Spencer, Richard (14 April 2009). "World's first cloned camel unveiled in Dubai". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ^ Ishfaq-ul-Hassan (15 March 2012). "India gets its second cloned animal Noorie, a pashmina goat". Daily News & Analysis. Kashmir, India.

- ^ "家畜体细胞克隆技术取得重大突破 ——成年体细胞克隆山羊诞生". Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Hickman, L. (18 March 2013). "Scientists clone extinct frog – Jurassic Park here we come?". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ Liu, Zhen; et al. (24 January 2018). "Cloning of Macaque Monkeys by Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer". Cell. 172 (4): 881–887.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.020. PMID 29395327.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (24 January 2018). "These monkey twins are the first primate clones made by the method that developed Dolly". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aat1066. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Briggs, Helen (24 January 2018). "First monkey clones created in Chinese laboratory". BBC News. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Scientists Successfully Clone Monkeys; Are Humans Up Next?". The New York Times. Associated Press. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Gene-edited disease monkeys cloned in China". EurekAlert!. Science China Press. 23 January 2019. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Ryan F. (23 January 2019). "China's Latest Cloned-Monkey Experiment Is an Ethical Mess". Gizmodo. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ "A black-footed ferret has been cloned, a first for a U.S. endangered species". Animals. 18 February 2021. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ Wei, Yanchang; Yang, Cai-Rong; Zhao, Zhen-Ao (22 March 2022). "Viable offspring derived from single unfertilized mammalian oocytes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (12) e2115248119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11915248W. doi:10.1073/pnas.2115248119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8944925. PMID 35254875.

- News article about the study: Magazine, Smithsonian; Osborne, Margaret. "Mice Birthed From Unfertilized Eggs for the First Time". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ Martinez, Bobby (26 January 2018). "Watch: Scientists clone monkeys using technique that created Dolly the sheep". Fox61. WTIC-TV. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ a b Kfoury, C (July 2007). "Therapeutic cloning: promises and issues". Mcgill J Med. 10 (2): 112–20. PMC 2323472. PMID 18523539.

- ^ "Cloning Fact Sheet". U.S. Department of Energy Genome Program. 11 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey; Rae, Michael (September 2007). Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs that Could Reverse Human Aging in Our Lifetime. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 416 pp. ISBN 0-312-36706-6.

- ^ Times Higher Education. 10 August 2001 In the news: Antinori and Zavos

- ^ "AAAS Statement on Human Cloning". Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ McGee, G. (October 2011). "Primer on Ethics and Human Cloning". American Institute of Biological Sciences. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights". UNESCO. 11 November 1997. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ^ McGee, Glenn (2000). The Perfect Baby: Parenthood in the New World of Cloning and Genetics. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Havstad JC (2010). "Human reproductive cloning: a conflict of liberties". Bioethics. 24 (2): 71–7. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00692.x. PMID 19076121. S2CID 40051820.

- ^ Engineering, Berkeley Master of (11 May 2020). "Op-ed: The dangers of cloning". Fung Institute for Engineering Leadership. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Bob Sullivan, Technology correspondent for NBC News. November 262003 Religions reveal little consensus on cloning – Health – Special Reports – Beyond Dolly: Human Cloning

- ^ Bainbridge, William Sims (October 2003). "Religious Opposition to Cloning" Archived 21 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Journal of Evolution and Technology. 13.

- ^ "Out of this world". The Guardian. 15 February 2002. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Raelian leader says cloning first step to immortality - Feb. 12, 2004". CNN. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Zitner, Aaron (29 March 2001). "Lawmakers Propose Human Cloning Ban, Alien Order Notwithstanding". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Huberman, Jenny (2 January 2018). "Immortality transformed: mind cloning, transhumanism and the quest for digital immortality". Mortality. 23 (1): 50–64. doi:10.1080/13576275.2017.1304366. ISSN 1357-6275. S2CID 152261367.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Eric (2022). "Everything and More: The Prospects of Whole Brain Emulation". Journal of Philosophy. 119 (8): 444–459. doi:10.5840/jphil2022119830. S2CID 252266788.

- ^ Godfrey, Alex (6 June 2019). "The science of Black Mirror's Ashley Too: will 'whole brain emulation' ever be possible?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Hanson, Robin (2016). The age of em: work, love, and life when robots rule the Earth (First ed.). Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-875462-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Watanabe, S (September 2013). "Effect of calf death loss on cloned cattle herd derived from somatic cell nuclear transfer: clones with congenital defects would be removed by the death loss". Animal Science Journal. 84 (9): 631–8. doi:10.1111/asj.12087. PMID 23829575.

- ^ "FDA says cloned animals are OK to eat". NBC News. Associated Press. 28 December 2006. Archived from the original on 13 June 2013.

- ^ "An HSUS Report: Welfare Issues with Genetic Engineering and Cloning of Farm Animals" (PDF). Humane Society of the United States. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2010.

- ^ Hansen, Michael (27 April 2007). "Comments of Consumers Union to US Food and Drug Administration on Docket No. 2003N-0573, Draft Animal Cloning Risk Assessment" (PDF). Consumers Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ^ Sandel, Michael J (2005). "The Ethical Implications of Human Cloning". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 48 (2): 241–247. doi:10.1353/pbm.2005.0063. ISSN 1529-8795. PMID 15834196. S2CID 32155922.

- ^ a b Holt, W. V., Pickard, A. R., & Prather, R. S. (2004) Wildlife conservation and reproductive cloning Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Reproduction, 126.

- ^ Ehrenfeld, David (2006). "Transgenics and Vertebrate Cloning as Tools for Species Conservation". Conservation Biology. 20 (3): 723–732. Bibcode:2006ConBi..20..723E. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00399.x. PMID 16909565. S2CID 12798003.

- ^ Ono T, Li C, Mizutani E, Terashita Y, Yamagata K, Wakayama T (December 2010). "Inhibition of class IIb histone deacetylase significantly improves cloning efficiency in mice". Biol. Reprod. 83 (6): 929–37. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.110.085282. PMID 20686182.

- ^ Shukman, David (14 January 2014) China cloning on an 'industrial scale' BBC News Science and Environment, Retrieved 27 February 2016

- ^ Baer, Drake (8 September 2015). "This Korean lab has nearly perfected dog cloning, and that's just the start". Tech Insider. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Ferris Jabr for Scientific American. 11 March 2013. Will cloning ever saved endangered species?

- ^ Heidi B. Perlman (8 October 2000). "Scientists Close on Extinct Cloning". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ Pence, Gregory E. (2005). Cloning After Dolly: Who's Still Afraid?. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-3408-7.

- ^ Strickland, Ashley (2 April 2022). "'Frozen zoos' may be a Noah's Ark for endangered animals". CNN. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Marshall, Andrew (2000). "Cloning for conservation". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (11): 1129. doi:10.1038/81057. PMID 11062403. S2CID 11078427.

- ^ "Conservation cloning". 2 December 2015.

- ^ Baker, Harry (14 March 2021). "Scientists want to store DNA of 6.7 million species on the moon, just in case – The 'lunar ark' would be hidden in lava tubes". Live Science. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Woodyatt, Amy (16 March 2021). "Scientists want to build a doomsday vault on the moon". CNN. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Engineers Propose Solar-Powered Lunar Ark as 'Modern Global Insurance Policy'". University of Arizona. 8 March 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Plans for 'doomsday ark' on the moon". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Werner, Debra (24 October 2022). "Sending DNA-infused Space Crystals to the moon". SpaceNews. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Ezell, Carson; Lazarian, Alexandre; Loeb, Abraham (December 2022). "A Lunar Backup Record of Humanity". Signals. 3 (4): 823–829. arXiv:2209.11155. doi:10.3390/signals3040049. ISSN 2624-6120.

- Article about the study: Tognetti, Laurence. "The moon is the perfect spot for humanity's offsite backup". Universe Today via phys.org. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "A Clone and His Mentor". sandiegozoo.org. San Diego Zoo. 20 October 2022. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Novak, Ben J.; Ryder, Oliver A.; Houck, Marlys L.; Putnam, Andrea S.; Walker, Kelcey; Russell, Lexie; Russell, Blake; Walker, Shawn; Arenivas, Sanaz Sadeghieh; Aston, Lauren; Veneklasen, Gregg; Ivy, Jamie A.; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Rusnak, Anna; Simek, Jaroslav; Zhuk, Anna; Phelan, Ryan (9 January 2024). "Endangered Przewalski's horse, Equus przewalskii, cloned from historically cryopreserved cells". bioRxiv 10.1101/2023.12.20.572538.

- ^ Szuszwalak, Joe (18 February 2021). "Innovative Genetic Research Boosts Black-footed Ferret Conservation Efforts by USFWS and Partners". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 22 February 2025.

- ^ Welk, Martin (1 November 2024). "Cloned ferret gives birth in Va., making history, U.S. officials say". The Washington Post. Yahoo. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ "Scientists 'to clone mammoth'". BBC News. 18 August 2003.

- ^ "BBC News". BBC. 7 December 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Когда вернутся мамонты" Archived 30 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine ("When the Mammoths Return"), 5 February 2015 (retrieved 6 September 2015)

- ^ Yong, Ed (15 March 2013). "Resurrecting the Extinct Frog with a Stomach for a Womb". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Long Now Foundation, Revive and Restore Project". 25 May 2017.

- ^ Lin, Jianqing; Duchêne, David; Carøe, Christian; Smith, Oliver; Ciucani, Marta Maria; Niemann, Jonas; Richmond, Douglas; Greenwood, Alex D.; MacPhee, Ross; Zhang, Guojie; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (11 April 2022). "Probing the genomic limits of de-extinction in the Christmas Island rat". Current Biology. 32 (7): 1650–1656.e3. Bibcode:2022CBio...32E1650L. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.02.027. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 9044923. PMID 35271794. S2CID 247323087.

- News report on the study: Ahmed, Issam. "Forget mammoths, study shows how to resurrect Christmas Island rats". phys.org. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia Is Going to Try to Clone an Army of 3,000-Year-Old Scythian Warriors". Popular Mechanics. 11 May 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Wehner, Mike (24 May 2021). "Does Russia really think it can clone ancient warriors?". BGR. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Lang, Fabienne (14 May 2021). "Russia's Defense Minister Wants to Clone 3000-Year-Old Scythian Army". interestingengineering.com. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Yes, We Should Clone Neanderthals". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Could we clone a Neanderthal?". BBC Science Focus Magazine. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Return of the Neanderthals". Science. 6 March 2013. Archived from the original on 17 February 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Lupkin, Sydney. "Harvard Prof Says Neanderthal Clones Possible but Experts Doubt It". ABC News. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Brown, Andrew (23 June 2011). "Should we clone Neanderthals?". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Lallanilla, Marc (21 January 2013). "Could a Surrogate Mother Deliver a Neanderthal Baby?". livescience.com. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "CNN – Nature – First cloned endangered species dies 2 days after birth – January 12, 2001". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Fresh effort to clone extinct animal". BBC News. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Endangered Species Cloning". www.elements.nb.ca. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Khan, Firdos Alam (3 September 2018). Biotechnology Fundamentals. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-315-36239-7.

- ^ Holloway, Grant (28 May 2002). "Cloning to revive extinct species". CNN.

- ^ "Researchers revive plan to clone the Tassie tiger". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 May 2005. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Gray, Richard; Dobson, Roger (31 January 2009). "Extinct ibex is resurrected by cloning". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ^ "Generations of Cloned Mice With Normal Lifespans Created: 25th Generation and Counting". Science Daily. 7 March 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ Carey, Nessa (2012). The Epigenetics Revolution. London, UK: Icon Books Ltd. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-184831-347-7.

- ^ Burgstaller, Jörg Patrick; Brem, Gottfried (2017). "Aging of Cloned Animals: A Mini-Review". Gerontology. 63 (5): 419. doi:10.1159/000452444. ISSN 0304-324X. PMID 27820924.

- ^ Sinclair, K. D.; Corr, S. A.; Gutierrez, C. G.; Fisher, P. A.; Lee, J.-H.; Rathbone, A. J.; Choi, I.; Campbell, K. H. S.; Gardner, D. S. (26 July 2016). "Healthy ageing of cloned sheep". Nature Communications. 7 12359. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712359S. doi:10.1038/ncomms12359. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4963533. PMID 27459299.

- ^ "Cloning Humans". Time. Vol. 142, no. 19. 8 November 1993. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Today The Sheep ..." Newsweek. 9 March 1997. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous; "Brave New World and Brave New World Revisited"; p. 19; HarperPerennial, 2005.

- ^ Bhelkar, Ratnakar D. (2009). Science Fiction: Fantasy and Reality. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 58. ISBN 978-81-269-1036-6. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ Stableford, Brian M. (2006). "Clone". Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-415-97460-8.

- ^ "Sleeper (1973)". IMDb. 17 December 1973. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Muir, John Kenneth (2007). A Critical History of Doctor Who on Television. McFarland. pp. 258–9. ISBN 978-1-4766-0454-1. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ Mumford, James (2013). Ethics at the Beginning of Life: A Phenomenological Critique. OUP Oxford. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-19-967396-4. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Humber, James M.; Almeder, Robert (1998). Human Cloning. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-59259-205-0. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Lewis, Courtland; Smithka, Paula (2010). "What's Continuity without Persistence?". Doctor Who and Philosophy: Bigger on the Inside. Open Court. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-8126-9725-4. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "Twice as nice: Barbra Streisand cloned her beloved dog and has 2 new pups". CBC News. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Streisand, Barbra (2 March 2018). "Barbra Streisand Explains: Why I Cloned My Dog". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b Clark, Michael. "Genetic themes in fiction films: Genetics meets Hollywood". The Wellcome Trust. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Hopkins, Patrick (1998). "How Popular media represent cloning as an ethical problem" (PDF). The Hastings Center Report. 28 (2): 6–13. doi:10.2307/3527566. JSTOR 3527566. PMID 9589288.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Yvonne A. De La Cruz Science Fiction Storytelling and Identity: Seeing the Human Through Android Eyes" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ "Uma Thurman, Rhys Ifans and Tom Wilkinson star in two plays for BBC Two" (Press release). BBC. 19 June 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- ^ "Review of Bunshin". 9 June 2012.

- ^ "Orphan Black (TV Series 2013– )". IMDb. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Banville, John (10 October 2004). "'The Double': The Tears of a Clone". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ Christian Lee Pyle (12 October 1978). "The Boys from Brazil (1978)". IMDb. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. (Spring 1973). "On Norman Spinrad's The Iron Dream". Science Fiction Studies. Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Daniel (2002). Cloning. Millbrook Press. ISBN 978-0-7613-2802-5. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2013). Doctor Who FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Most Famous Time Lord in the Universe. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4803-4295-8. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ Barr, Jason; Mustachio, Camille D. G. (2014). The Language of Doctor Who: From Shakespeare to Alien Tongues. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-4422-3481-9. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ McDonald, Paul F. (2013). "The Clones". The Star Wars Heresies: Interpreting the Themes, Symbols and Philosophies of Episodes I, II and III. McFarland. pp. 167–171. ISBN 978-0-7864-7181-2. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008)". IMDb. 15 August 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Never Let Me Go (2010)". IMDb. 11 February 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "The Island (2005)". IMDb. 22 July 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Moon (2009)". IMDb. 17 July 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Technology News – 2017 Innovations and Future Tech". Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2013.