Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Biomedical engineering

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

Biomedical engineering (BME) or medical engineering is the application of engineering principles and design concepts to medicine and biology for healthcare applications (e.g., diagnostic or therapeutic purposes). BME also integrates the logical sciences to advance health care treatment, including diagnosis, monitoring, and therapy.[1][2] Also included under the scope of a biomedical engineer is the management of current medical equipment in hospitals while adhering to relevant industry standards. This involves procurement, routine testing, preventive maintenance, and making equipment recommendations, a role also known as a Biomedical Equipment Technician (BMET) or as a clinical engineer.

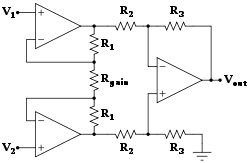

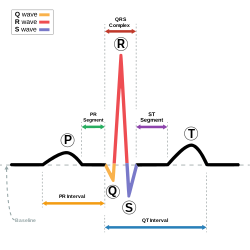

Biomedical engineering has recently emerged as its own field of, as compared to many other engineering fields.[3] Such an evolution is common as a new field transitions from being an interdisciplinary specialization among already-established fields to being considered a field in itself. Much of the work in biomedical engineering consists of research and development, spanning a broad array of subfields (see below). Prominent biomedical engineering applications include the development of biocompatible prostheses, various diagnostic and therapeutic medical devices ranging from clinical equipment to micro-implants, imaging technologies such as MRI and EKG/ECG, regenerative tissue growth, and the development of pharmaceutical drugs including biopharmaceuticals.

Subfields and related fields

[edit]Bioinformatics

[edit]

Bioinformatics is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biological data. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combines computer science, statistics, mathematics, and engineering to analyze and interpret biological data.

Bioinformatics is considered both an umbrella term for the body of biological studies that use computer programming as part of their methodology, as well as a reference to specific analysis "pipelines" that are repeatedly used, particularly in the field of genomics. Common uses of bioinformatics include the identification of candidate genes and nucleotides (SNPs). Often, such identification is made with the aim of better understanding the genetic basis of disease, unique adaptations, desirable properties (esp. in agricultural species), or differences between populations. In a less formal way, bioinformatics also tries to understand the organizational principles within nucleic acid and protein sequences.

Biomechanics

[edit]

Biomechanics is the study of the structure and function of the mechanical aspects of biological systems, at any level from whole organisms to organs, cells and cell organelles,[4] using the methods of mechanics.[5]

Biomaterials

[edit]A biomaterial is any matter, surface, or construct that interacts with living systems. As a science, biomaterials is about fifty years old. The study of biomaterials is called biomaterials science or biomaterials engineering. It has experienced steady and strong growth over its history, with many companies investing large amounts of money into the development of new products. Biomaterials science encompasses elements of medicine, biology, chemistry, tissue engineering and materials science.

Biomedical optics

[edit]Biomedical optics combines the principles of physics, engineering, and biology to study the interaction of biological tissue and light, and how this can be exploited for sensing, imaging, and treatment.[6] It has a wide range of applications, including optical imaging, microscopy, ophthalmoscopy, spectroscopy, and therapy. Examples of biomedical optics techniques and technologies include optical coherence tomography (OCT), fluorescence microscopy, confocal microscopy, and photodynamic therapy (PDT). OCT, for example, uses light to create high-resolution, three-dimensional images of internal structures, such as the retina in the eye or the coronary arteries in the heart. Fluorescence microscopy involves labeling specific molecules with fluorescent dyes and visualizing them using light, providing insights into biological processes and disease mechanisms. More recently, adaptive optics is helping imaging by correcting aberrations in biological tissue, enabling higher resolution imaging and improved accuracy in procedures such as laser surgery and retinal imaging.

Tissue engineering

[edit]Tissue engineering, like genetic engineering (see below), is a major segment of biotechnology – which overlaps significantly with BME.

One of the goals of tissue engineering is to create artificial organs (via biological material) such as kidneys, livers, for patients that need organ transplants. Biomedical engineers are currently researching methods of creating such organs. Researchers have grown solid jawbones[7] and tracheas[8] from human stem cells towards this end. Several artificial urinary bladders have been grown in laboratories and transplanted successfully into human patients.[9] Bioartificial organs, which use both synthetic and biological component, are also a focus area in research, such as with hepatic assist devices that use liver cells within an artificial bioreactor construct.[10]

Genetic engineering

[edit]Genetic engineering, recombinant DNA technology, genetic modification/manipulation (GM) and gene splicing are terms that apply to the direct manipulation of an organism's genes. Unlike traditional breeding, an indirect method of genetic manipulation, genetic engineering utilizes modern tools such as molecular cloning and transformation to directly alter the structure and characteristics of target genes. Genetic engineering techniques have found success in numerous applications. Some examples include the improvement of crop technology (not a medical application, but see biological systems engineering), the manufacture of synthetic human insulin through the use of modified bacteria, the manufacture of erythropoietin in hamster ovary cells, and the production of new types of experimental mice such as the oncomouse (cancer mouse) for research.[citation needed]

Neural engineering

[edit]Neural engineering (also known as neuroengineering) is a discipline that uses engineering techniques to understand, repair, replace, or enhance neural systems. Neural engineers are uniquely qualified to solve design problems at the interface of living neural tissue and non-living constructs. Neural engineering can assist with numerous things, including the future development of prosthetics. For example, cognitive neural prosthetics (CNP) are being heavily researched and would allow for a chip implant to assist people who have prosthetics by providing signals to operate assistive devices.[11]

Pharmaceutical engineering

[edit]Pharmaceutical engineering is an interdisciplinary science that includes drug engineering, novel drug delivery and targeting, pharmaceutical technology, unit operations of chemical engineering, and pharmaceutical analysis. It may be deemed as a part of pharmacy due to its focus on the use of technology on chemical agents in providing better medicinal treatment.

Hospital and medical devices

[edit]

This is an extremely broad category—essentially covering all health care products that do not achieve their intended results through predominantly chemical (e.g., pharmaceuticals) or biological (e.g., vaccines) means, and do not involve metabolism.

A medical device is intended for use in:

- the diagnosis of disease or other conditions

- in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease.

Some examples include pacemakers, infusion pumps, the heart-lung machine, dialysis machines, artificial organs, implants, artificial limbs, corrective lenses, cochlear implants, ocular prosthetics, facial prosthetics, somato prosthetics, and dental implants.

Stereolithography is a practical example of medical modeling being used to create physical objects. Beyond modeling organs and the human body, emerging engineering techniques are also currently used in the research and development of new devices for innovative therapies,[12] treatments,[13] patient monitoring,[14] of complex diseases.

Medical devices are regulated and classified (in the US) as follows (see also Regulation):

- Class I devices present minimal potential for harm to the user and are often simpler in design than Class II or Class III devices. Devices in this category include tongue depressors, bedpans, elastic bandages, examination gloves, and hand-held surgical instruments, and other similar types of common equipment.

- Class II devices are subject to special controls in addition to the general controls of Class I devices. Special controls may include special labeling requirements, mandatory performance standards, and postmarket surveillance. Devices in this class are typically non-invasive and include X-ray machines, PACS, powered wheelchairs, infusion pumps, and surgical drapes.

- Class III devices generally require premarket approval (PMA) or premarket notification (510k), a scientific review to ensure the device's safety and effectiveness, in addition to the general controls of Class I. Examples include replacement heart valves, hip and knee joint implants, silicone gel-filled breast implants, implanted cerebellar stimulators, implantable pacemaker pulse generators and endosseous (intra-bone) implants.

Medical imaging

[edit]Medical/biomedical imaging is a major segment of medical devices. This area deals with enabling clinicians to directly or indirectly "view" things not visible in plain sight (such as due to their size, and/or location). This can involve utilizing ultrasound, magnetism, UV, radiology, and other means.

Alternatively, navigation-guided equipment utilizes electromagnetic tracking technology, such as catheter placement into the brain or feeding tube placement systems. For example, ENvizion Medical's ENvue, an electromagnetic navigation system for enteral feeding tube placement. The system uses an external field generator and several EM passive sensors enabling scaling of the display to the patient's body contour, and a real-time view of the feeding tube tip location and direction, which helps the medical staff ensure the correct placement in the GI tract.[15]

Imaging technologies are often essential to medical diagnosis, and are typically the most complex equipment found in a hospital including: fluoroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nuclear medicine, positron emission tomography (PET), PET-CT scans, projection radiography such as X-rays and CT scans, tomography, ultrasound, optical microscopy, and electron microscopy.

Medical implants

[edit]An implant is a kind of medical device made to replace and act as a missing biological structure (as compared with a transplant, which indicates transplanted biomedical tissue). The surface of implants that contact the body might be made of a biomedical material such as titanium, silicone or apatite depending on what is the most functional. In some cases, implants contain electronics, e.g. artificial pacemakers and cochlear implants. Some implants are bioactive, such as subcutaneous drug delivery devices in the form of implantable pills or drug-eluting stents.

Bionics

[edit]Artificial body part replacements are one of the many applications of bionics. Concerned with the intricate and thorough study of the properties and function of human body systems, bionics may be applied to solve some engineering problems. Careful study of the different functions and processes of the eyes, ears, and other organs paved the way for improved cameras, television, radio transmitters and receivers, and many other tools.

Biomedical sensors

[edit]In recent years biomedical sensors based in microwave technology have gained more attention. Different sensors can be manufactured for specific uses in both diagnosing and monitoring disease conditions, for example microwave sensors can be used as a complementary technique to X-ray to monitor lower extremity trauma.[16] The sensor monitor the dielectric properties and can thus notice change in tissue (bone, muscle, fat etc.) under the skin so when measuring at different times during the healing process the response from the sensor will change as the trauma heals.

Clinical engineering

[edit]Clinical engineering is the branch of biomedical engineering dealing with the actual implementation of medical equipment and technologies in hospitals or other clinical settings. Major roles of clinical engineers include training and supervising biomedical equipment technicians (BMETs), selecting technological products/services and logistically managing their implementation, working with governmental regulators on inspections/audits, and serving as technological consultants for other hospital staff (e.g. physicians, administrators, I.T., etc.). Clinical engineers also advise and collaborate with medical device producers regarding prospective design improvements based on clinical experiences, as well as monitor the progression of the state of the art so as to redirect procurement patterns accordingly.

Their inherent focus on practical implementation of technology has tended to keep them oriented more towards incremental-level redesigns and reconfigurations, as opposed to revolutionary research & development or ideas that would be many years from clinical adoption; however, there is a growing effort to expand this time-horizon over which clinical engineers can influence the trajectory of biomedical innovation. In their various roles, they form a "bridge" between the primary designers and the end-users, by combining the perspectives of being both close to the point-of-use, while also trained in product and process engineering. Clinical engineering departments will sometimes hire not just biomedical engineers, but also industrial/systems engineers to help address operations research/optimization, human factors, cost analysis, etc. Also, see safety engineering for a discussion of the procedures used to design safe systems. The clinical engineering department is constructed with a manager, supervisor, engineer, and technician. One engineer per eighty beds in the hospital is the ratio. Clinical engineers are also authorized to audit pharmaceutical and associated stores to monitor FDA recalls of invasive items.

Rehabilitation engineering

[edit]

Rehabilitation engineering is the systematic application of engineering sciences to design, develop, adapt, test, evaluate, apply, and distribute technological solutions to problems confronted by individuals with disabilities. Functional areas addressed through rehabilitation engineering may include mobility, communications, hearing, vision, and cognition, and activities associated with employment, independent living, education, and integration into the community.[1]

While some rehabilitation engineers have master's degrees in rehabilitation engineering, usually a subspecialty of Biomedical engineering, most rehabilitation engineers have an undergraduate or graduate degrees in biomedical engineering, mechanical engineering, or electrical engineering. A Portuguese university provides an undergraduate degree and a master's degree in Rehabilitation Engineering and Accessibility.[7][9] Qualification to become a Rehab' Engineer in the UK is possible via a University BSc Honours Degree course such as Health Design & Technology Institute, Coventry University.[10]

The rehabilitation process for people with disabilities often entails the design of assistive devices such as Walking aids intended to promote the inclusion of their users into the mainstream of society, commerce, and recreation.

Regulatory issues

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

Regulatory issues have been constantly increased in the last decades to respond to the many incidents caused by devices to patients. For example, from 2008 to 2011, in US, there were 119 FDA recalls of medical devices classified as class I. According to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Class I recall is associated to "a situation in which there is a reasonable probability that the use of, or exposure to, a product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death"[17]

Regardless of the country-specific legislation, the main regulatory objectives coincide worldwide.[18] For example, in the medical device regulations, a product must be 1), safe 2), effective and 3), applicable to all the manufactured devices.

A product is safe if patients, users, and third parties do not run unacceptable risks of physical hazards, such as injury or death, in its intended use. Protective measures must be introduced on devices that are hazardous to reduce residual risks at an acceptable level if compared with the benefit derived from the use of it.

A product is effective if it performs as specified by the manufacturer in the intended use. Proof of effectiveness is achieved through clinical evaluation, compliance to performance standards or demonstrations of substantial equivalence with an already marketed device.

The previous features have to be ensured for all the manufactured items of the medical device. This requires that a quality system shall be in place for all the relevant entities and processes that may impact safety and effectiveness over the whole medical device lifecycle.

The medical device engineering area is among the most heavily regulated fields of engineering, and practicing biomedical engineers must routinely consult and cooperate with regulatory law attorneys and other experts. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the principal healthcare regulatory authority in the United States, having jurisdiction over medical devices, drugs, biologics, and combination products. The paramount objectives driving policy decisions by the FDA are safety and effectiveness of healthcare products that have to be assured through a quality system in place as specified under 21 CFR 829 regulation. In addition, because biomedical engineers often develop devices and technologies for "consumer" use, such as physical therapy devices (which are also "medical" devices), these may also be governed in some respects by the Consumer Product Safety Commission. The greatest hurdles tend to be 510K "clearance" (typically for Class 2 devices) or pre-market "approval" (typically for drugs and class 3 devices).

In the European context, safety effectiveness and quality is ensured through the "Conformity Assessment" which is defined as "the method by which a manufacturer demonstrates that its device complies with the requirements of the European Medical Device Directive". The directive specifies different procedures according to the class of the device ranging from the simple Declaration of Conformity (Annex VII) for Class I devices to EC verification (Annex IV), Production quality assurance (Annex V), Product quality assurance (Annex VI) and Full quality assurance (Annex II). The Medical Device Directive specifies detailed procedures for Certification. In general terms, these procedures include tests and verifications that are to be contained in specific deliveries such as the risk management file, the technical file, and the quality system deliveries. The risk management file is the first deliverable that conditions the following design and manufacturing steps. The risk management stage shall drive the product so that product risks are reduced at an acceptable level with respect to the benefits expected for the patients for the use of the device. The technical file contains all the documentation data and records supporting medical device certification. FDA technical file has similar content although organized in a different structure. The Quality System deliverables usually include procedures that ensure quality throughout all product life cycles. The same standard (ISO EN 13485) is usually applied for quality management systems in the US and worldwide.

In the European Union, there are certifying entities named "Notified Bodies", accredited by the European Member States. The Notified Bodies must ensure the effectiveness of the certification process for all medical devices apart from the class I devices where a declaration of conformity produced by the manufacturer is sufficient for marketing. Once a product has passed all the steps required by the Medical Device Directive, the device is entitled to bear a CE marking, indicating that the device is believed to be safe and effective when used as intended, and, therefore, it can be marketed within the European Union area.

The different regulatory arrangements sometimes result in particular technologies being developed first for either the U.S. or in Europe depending on the more favorable form of regulation. While nations often strive for substantive harmony to facilitate cross-national distribution, philosophical differences about the optimal extent of regulation can be a hindrance; more restrictive regulations seem appealing on an intuitive level, but critics decry the tradeoff cost in terms of slowing access to life-saving developments.

RoHS II

[edit]Directive 2011/65/EU, better known as RoHS 2 is a recast of legislation originally introduced in 2002. The original EU legislation "Restrictions of Certain Hazardous Substances in Electrical and Electronics Devices" (RoHS Directive 2002/95/EC) was replaced and superseded by 2011/65/EU published in July 2011 and commonly known as RoHS 2. RoHS seeks to limit the dangerous substances in circulation in electronics products, in particular toxins and heavy metals, which are subsequently released into the environment when such devices are recycled.

The scope of RoHS 2 is widened to include products previously excluded, such as medical devices and industrial equipment. In addition, manufacturers are now obliged to provide conformity risk assessments and test reports – or explain why they are lacking. For the first time, not only manufacturers but also importers and distributors share a responsibility to ensure Electrical and Electronic Equipment within the scope of RoHS complies with the hazardous substances limits and have a CE mark on their products.

IEC 60601

[edit]The new International Standard IEC 60601 for home healthcare electro-medical devices defining the requirements for devices used in the home healthcare environment. IEC 60601-1-11 (2010) must now be incorporated into the design and verification of a wide range of home use and point of care medical devices along with other applicable standards in the IEC 60601 3rd edition series.

The mandatory date for implementation of the EN European version of the standard is June 1, 2013. The US FDA requires the use of the standard on June 30, 2013, while Health Canada recently extended the required date from June 2012 to April 2013. The North American agencies will only require these standards for new device submissions, while the EU will take the more severe approach of requiring all applicable devices being placed on the market to consider the home healthcare standard.

AS/NZS 3551:2012

[edit]AS/ANS 3551:2012 is the Australian and New Zealand standards for the management of medical devices. The standard specifies the procedures required to maintain a wide range of medical assets in a clinical setting (e.g. Hospital).[19] The standards are based on the IEC 606101 standards.

The standard covers a wide range of medical equipment management elements including, procurement, acceptance testing, maintenance (electrical safety and preventive maintenance testing) and decommissioning.

Training and certification

[edit]Education

[edit]Biomedical engineers require considerable knowledge of both engineering and biology, and typically have a Bachelor's (B.Sc., B.S., B.Eng. or B.S.E.) or Master's (M.S., M.Sc., M.S.E., or M.Eng.) or a doctoral (Ph.D., or MD-PhD[20][21][22]) degree in BME (Biomedical Engineering) or another branch of engineering with considerable potential for BME overlap. As interest in BME increases, many engineering colleges now have a Biomedical Engineering Department or Program, with offerings ranging from the undergraduate (B.Sc., B.S., B.Eng. or B.S.E.) to doctoral levels. Biomedical engineering has only recently been emerging as its own discipline rather than a cross-disciplinary hybrid specialization of other disciplines; and BME programs at all levels are becoming more widespread, including the Bachelor of Science in Biomedical Engineering which includes enough biological science content that many students use it as a "pre-med" major in preparation for medical school. The number of biomedical engineers is expected to rise as both a cause and effect of improvements in medical technology.[23]

In the U.S., an increasing number of undergraduate programs are also becoming recognized by ABET as accredited bioengineering/biomedical engineering programs. As of 2023, 155 programs are currently accredited by ABET.[24]

In Canada and Australia, accredited graduate programs in biomedical engineering are common.[25] For example, McMaster University offers an M.A.Sc, an MD/PhD, and a PhD in Biomedical engineering.[26] The first Canadian undergraduate BME program was offered at University of Guelph as a four-year B.Eng. program.[27] The Polytechnique in Montreal is also offering a bachelors's degree in biomedical engineering[28] as is Flinders University.[29]

As with many degrees, the reputation and ranking of a program may factor into the desirability of a degree holder for either employment or graduate admission. The reputation of many undergraduate degrees is also linked to the institution's graduate or research programs, which have some tangible factors for rating, such as research funding and volume, publications and citations. With BME specifically, the ranking of a university's hospital and medical school can also be a significant factor in the perceived prestige of its BME department/program.

Graduate education is a particularly important aspect in BME. While many engineering fields (such as mechanical or electrical engineering) do not need graduate-level training to obtain an entry-level job in their field, the majority of BME positions do prefer or even require them.[30] Since most BME-related professions involve scientific research, such as in pharmaceutical and medical device development, graduate education is almost a requirement (as undergraduate degrees typically do not involve sufficient research training and experience). This can be either a Masters or Doctoral level degree; while in certain specialties a Ph.D. is notably more common than in others, it is hardly ever the majority (except in academia). In fact, the perceived need for some kind of graduate credential is so strong that some undergraduate BME programs will actively discourage students from majoring in BME without an expressed intention to also obtain a master's degree or apply to medical school afterwards.

Graduate programs in BME, like in other scientific fields, are highly varied, and particular programs may emphasize certain aspects within the field. They may also feature extensive collaborative efforts with programs in other fields (such as the university's Medical School or other engineering divisions), owing again to the interdisciplinary nature of BME. M.S. and Ph.D. programs will typically require applicants to have an undergraduate degree in BME, or another engineering discipline (plus certain life science coursework), or life science (plus certain engineering coursework).

Education in BME also varies greatly around the world. By virtue of its extensive biotechnology sector, its numerous major universities, and relatively few internal barriers, the U.S. has progressed a great deal in its development of BME education and training opportunities. Europe, which also has a large biotechnology sector and an impressive education system, has encountered trouble in creating uniform standards as the European community attempts to supplant some of the national jurisdictional barriers that still exist. Recently, initiatives such as BIOMEDEA have sprung up to develop BME-related education and professional standards.[31] Other countries, such as Australia, are recognizing and moving to correct deficiencies in their BME education.[32] Also, as high technology endeavors are usually marks of developed nations, some areas of the world are prone to slower development in education, including in BME.

Licensure/certification

[edit]As with other learned professions, each state has certain (fairly similar) requirements for becoming licensed as a registered Professional Engineer (PE), but, in US, in industry such a license is not required to be an employee as an engineer in the majority of situations (due to an exception known as the industrial exemption, which effectively applies to the vast majority of American engineers). The US model has generally been only to require the practicing engineers offering engineering services that impact the public welfare, safety, safeguarding of life, health, or property to be licensed, while engineers working in private industry without a direct offering of engineering services to the public or other businesses, education, and government need not be licensed. This is notably not the case in many other countries, where a license is as legally necessary to practice engineering as it is for law or medicine.

Biomedical engineering is regulated in some countries, such as Australia, but registration is typically only recommended and not required.[33]

In the UK, mechanical engineers working in the areas of Medical Engineering, Bioengineering or Biomedical engineering can gain Chartered Engineer status through the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. The Institution also runs the Engineering in Medicine and Health Division.[34] The Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine (IPEM) has a panel for the accreditation of MSc courses in Biomedical Engineering and Chartered Engineering status can also be sought through IPEM.

The Fundamentals of Engineering exam – the first (and more general) of two licensure examinations for most U.S. jurisdictions—does now cover biology (although technically not BME). For the second exam, called the Principles and Practices, Part 2, or the Professional Engineering exam, candidates may select a particular engineering discipline's content to be tested on; there is currently not an option for BME with this, meaning that any biomedical engineers seeking a license must prepare to take this examination in another category (which does not affect the actual license, since most jurisdictions do not recognize discipline specialties anyway). However, the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) is, as of 2009, exploring the possibility of seeking to implement a BME-specific version of this exam to facilitate biomedical engineers pursuing licensure.

Beyond governmental registration, certain private-sector professional/industrial organizations also offer certifications with varying degrees of prominence. One such example is the Certified Clinical Engineer (CCE) certification for Clinical engineers.

Career prospects

[edit]In 2012 there were about 19,400 biomedical engineers employed in the US, and the field was predicted to grow by 5% (faster than average) from 2012 to 2022.[35] Biomedical engineering has the highest percentage of female engineers compared to other common engineering professions. Now as of 2023, there are 19,700 jobs for this degree, the average pay for a person in this field is around $100,730.00 and making around $48.43 an hour. There is also expected to be a 7% increase in jobs from here 2023 to 2033 (even faster than the last average).

Notable figures

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2016) |

- Julia Tutelman Apter (deceased) – One of the first specialists in neurophysiological research[36] and a founding member of the Biomedical Engineering Society[37]

- Earl Bakken (deceased) – Invented the first transistorised pacemaker, co-founder of Medtronic.

- Forrest Bird (deceased) – aviator and pioneer in the invention of mechanical ventilators

- Y.C. Fung (deceased) – professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego, considered by many to be the founder of modern biomechanics[38]

- Leslie Geddes (deceased) – professor emeritus at Purdue University, electrical engineer, inventor, and educator of over 2000 biomedical engineers, received a National Medal of Technology in 2006 from President George Bush[39] for his more than 50 years of contributions that have spawned innovations ranging from burn treatments to miniature defibrillators, ligament repair to tiny blood pressure monitors for premature infants, as well as a new method for performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

- Willem Johan Kolff (deceased) – pioneer of hemodialysis as well as in the field of artificial organs

- Robert Langer – Institute Professor at MIT, runs the largest BME laboratory in the world, pioneer in drug delivery and tissue engineering[40]

- John Macleod (deceased) – one of the co-discoverers of insulin at Case Western Reserve University.

- Alfred E. Mann – Physicist, entrepreneur and philanthropist. A pioneer in the field of Biomedical Engineering.[41]

- J. Thomas Mortimer – Emeritus professor of biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve University. Pioneer in Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES)[42]

- Robert M. Nerem – professor emeritus at Georgia Institute of Technology. Pioneer in regenerative tissue, biomechanics, and author of over 300 published works. His works have been cited more than 20,000 times cumulatively.

- P. Hunter Peckham – Donnell Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Orthopaedics at Case Western Reserve University. Pioneer in Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES)[43]

- Nicholas A. Peppas – Chaired Professor in Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, pioneer in drug delivery, biomaterials, hydrogels and nanobiotechnology.

- Robert Plonsey – professor emeritus at Duke University, pioneer of electrophysiology[44]

- Otto Schmitt (deceased) – biophysicist with significant contributions to BME, working with biomimetics

- Ascher Shapiro (deceased) – Institute Professor at MIT, contributed to the development of the BME field, medical devices (e.g. intra-aortic balloons)

- Gordana Vunjak-Novakovic – University Professor at Columbia University, pioneer in tissue engineering and bioreactor design

- John G. Webster – professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, a pioneer in the field of instrumentation amplifiers for the recording of electrophysiological signals

- Fred Weibell, coauthor of Biomedical Instrumentation and Measurements

- U.A. Whitaker (deceased) – provider of the Whitaker Foundation, which supported research and education in BME by providing over $700 million to various universities, helping to create 30 BME programs and helping finance the construction of 13 buildings[45]

See also

[edit]- Biomedicine – Branch of medical science

- Cardiophysics

- Computational anatomy – Interdisciplinary field of biology

- Medical physics – Application of physics in medicine or healthcare

- Physiome – Wholistic physiological dynamics of an organism

- Biomedical Engineering and Instrumentation Program (BEIP)

References

[edit]- ^ a b John Denis Enderle; Joseph D. Bronzino (2012). Introduction to Biomedical Engineering. Academic Press. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-0-12-374979-6. Archived from the original on 2024-07-26. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ Fakhrullin, Rawil; Lvov, Yuri, eds. (2014). Cell Surface Engineering. Smart Materials Series. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. doi:10.1039/9781782628477. ISBN 978-1-78262-847-7. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- ^ Nebeker, Frederik (2001). "The Emergence of Biomedical Engineering in the United States". International Committee for the History of Technology. 7: 75–94. JSTOR 23786025.

- ^ Alexander R. McNeill (2005). "Mechanics of animal movement". Current Biology. 15 (16): R616 – R619. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.016. PMID 16111929. S2CID 14032136.

- ^ Hatze, Herbert (1974). "The meaning of the term biomechanics". Journal of Biomechanics. 7 (12): 189–190. doi:10.1016/0021-9290(74)90060-8. PMID 4837555.

- ^ "Introduction to Biomedical Optics" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-07-26. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- ^ a b "Jaw bone created from stem cells". BBC News. October 10, 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ Walles T. Tracheobronchial bio-engineering: biotechnology fulfilling unmet medical needs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011; 63(4–5): 367–74.

- ^ a b "Doctors grow organs from patients' own cells". CNN. April 3, 2006. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- ^ a b Trial begins for first artificial liver device using human cells Archived 2011-01-05 at the Wayback Machine, University of Chicago, February 25, 1999

- ^ Andersen, Richard A.; Hwang, Eun Jung; Mulliken, Grant H. (2010). "Cognitive Neural Prosthetics". Annual Review of Psychology. 61: 169–C3. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100503. ISSN 0066-4308. PMC 2849803. PMID 19575625.

- ^ Hede, Shantesh; Huilgol, Nagraj (October 2006). ""Nano": The new nemesis of cancer Hede S, Huilgol N – J Can Res Ther". cancerjournal.net. 2 (4). Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ^ Couvreur, Patrick; Vauthier, Christine (2006). "Nanotechnology: Intelligent Design to Treat Complex Disease". Pharmaceutical Research. 23 (7): 1417–1450(34). doi:10.1007/s11095-006-0284-8. PMID 16779701. S2CID 1520698.

- ^ Curtis, Adam SG; Dalby, Matthew; Gadegaard, Nikolaj (2006). "Cell signaling arising from nanotopography: implications for nanomedical devices". Nanomedicine. 1 (1): 67–72. doi:10.2217/17435889.1.1.67. ISSN 1743-5889. PMID 17716210.

- ^ Jacobson, Lewis E.; Olayan, May; Williams, Jamie M.; Schultz, Jacqueline F.; Wise, Hannah M.; Singh, Amandeep; Saxe, Jonathan M.; Benjamin, Richard; Emery, Marie; Vilem, Hilary; Kirby, Donald F. (1 November 2019). "Feasibility and safety of a novel electromagnetic device for small-bore feeding tube placement". Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open. 4 (1) e000330. doi:10.1136/tsaco-2019-000330. ISSN 2397-5776. PMC 6861064. PMID 31799414. Archived from the original on 3 March 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ Shah, Syaiful; Velander, Jacob; Mathur, Parul; Perez, Mauricio; Asan, Noor; Kurup, Dhanesh; Blokhuis, Taco; Augustine, Robin (2018-02-21). "Split-Ring Resonator Sensor Penetration Depth Assessment Using in Vivo Microwave Reflectivity and Ultrasound Measurements for Lower Extremity Trauma Rehabilitation". Sensors. 18 (2): 636. Bibcode:2018Senso..18..636S. doi:10.3390/s18020636. ISSN 1424-8220. PMC 5855979. PMID 29466312.

- ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Medical & Radiation Emitting Device Recalls [1]

- ^ "Medical Device Regulations: Global overview and guiding principles" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-25. Retrieved 2013-09-13.

- ^ AS/NZS 3551:2012 Management programs for medical equipment. Standards Australia. 2016-10-18. ISBN 978-1-74342-277-9. Archived from the original on 2014-03-11. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ^ "MD-PhD Program". Johns Hopkins Biomedical Engineering. Archived from the original on 2022-11-29. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ^ "PhD+MD". Dartmouth Engineering. Archived from the original on 2022-11-29. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ^ "Physician-Engineer Training Program". Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering – Purdue University. Archived from the original on 2022-11-29. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics – Profile for Engineers Archived February 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Disciplines. Countries. USA". Archived from the original on 2023-02-20. Retrieved 2023-02-20.

- ^ Goyal, Megh R. (2018-01-03). Scientific and Technical Terms in Bioengineering and Biological Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-351-36035-7. Archived from the original on 2024-07-26. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ "Degree Options". McMaster School of Biomedical Engineering. eng.mcmaster.ca. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ "2010–2011 Undergraduate Calendar – Biomedical Engineering". University of Guelph. 2010-09-07. Archived from the original on 2024-07-26. Retrieved 2024-04-07.

- ^ "Baccalauréat en Génie biomédical". Polytechnique Montréal. 15 January 2018. Archived from the original on 12 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Bachelor of Engineering (Biomedical) (Honours)". Flinders University. Archived from the original on 26 July 2024. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ "Job Outlook for Engineers". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Archived from the original on December 19, 2011.

- ^ "BIOMEDEA". September 2005. Archived from the original on May 6, 2008.

- ^ Lithgow, B. J. (October 25, 2001). "Biomedical Engineering Curriculum: A Comparison Between the USA, Europe and Australia". Archived from the original on May 1, 2008.

- ^ "National Engineering Register". Engineers Australia. Archived from the original on 5 January 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Medical Engineering: Homepage". Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Archived from the original on May 2, 2007.

- ^ Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2014–15 Edition: Biomedical Engineers Archived 2021-04-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Dr. Julia Apter, Ophthalmologist And Researcher, 61, in Chicago". The New York Times. 1979-04-18. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-03-01. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ Fagette Jr., Paul H.; Horner, Patricia I., eds. (2004). Celebrating 35 years of Biomedical Engineering: An Historical Perspective (PDF). Landover, MD: Biomedical Engineering Society. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-01. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ Kassab, Ghassan S. (2004). "YC "Bert" Fung: The Father of Modern Biomechanics" (PDF). Mechanics & Chemistry of Biosystems. 1 (1). Tech Science Press: 5–22. doi:10.3970/mcb.2004.001.005. PMID 16783943. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2007.

- ^ "Leslie Geddes – 2006 National Medal of Technology". 2007-07-31. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2011-09-24 – via YouTube.

- ^ O'Neill, Kathryn M. (July 20, 2006). "Colleagues honor Langer for 30 years of innovation". MIT News Office. Archived from the original on February 18, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2007.

- ^ Gallegos, Emma (2010-10-25). "Alfred E. Mann Foundation for Scientific Research (AMF)". Aemf.org. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ^ "J. Thomas Mortimer". CSE Faculty/Staff Profiles. engineering.case.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-05-02. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ^ "P. Hunter Peckham, PhD | Distinguished University Professor | Case Western Reserve University". Distinguished University Professor | Case Western Reserve University. 25 April 2018. Archived from the original on 2024-07-26. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ^ "Robert Plonsey, Pfizer-Pratt Professor Emeritus". Faculty – Duke BME. Fds.duke.edu. Archived from the original on 2009-06-05. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ^ "The Whitaker Foundation". Whitaker.org. Archived from the original on 2011-09-25. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

45. ^Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, "Bioengineers and Biomedical Engineers", retrieved October 27, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Bronzino, Joseph D. (April 2006). The Biomedical Engineering Handbook (Third ed.). [CRC Press]. ISBN 978-0-8493-2124-5. Archived from the original on 2015-02-24. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- Villafane, Carlos (June 2009). Biomed: From the Student's Perspective (First ed.). [Techniciansfriend.com]. ISBN 978-1-61539-663-4. Archived from the original on 2021-02-13. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

External links

[edit] Media related to Biomedical engineering at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Biomedical engineering at Wikimedia Commons

Biomedical engineering

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Scope

Biomedical engineering applies engineering principles, practices, and technologies to medicine and biology, primarily to solve problems in healthcare through the design of devices, systems, and processes. This discipline integrates physical, chemical, mathematical, and computational sciences with biological knowledge to develop solutions that address diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive needs.[2] Core activities involve creating equipment and software that enable precise measurement, modeling, and intervention in biological systems, grounded in testable hypotheses and reproducible outcomes.[3] The scope extends to hardware innovations such as implantable devices and diagnostic imaging systems, software for analyzing physiological data, and engineered biological materials like scaffolds for tissue regeneration, all validated through empirical experimentation and causal validation of mechanisms.[1] These efforts prioritize scalable technologies that enhance human health by leveraging quantitative analysis over qualitative observation alone.[11] Biomedical engineers focus on iterative design cycles informed by data from controlled studies, ensuring interventions target underlying physiological causes rather than symptomatic relief.[12] In distinction from pure medical practice or biological research, biomedical engineering emphasizes engineering rigor—employing mathematics, physics, and computational modeling to produce standardized, manufacturable solutions deployable at scale, rather than individualized clinical procedures or exploratory studies.[13] This approach demands adherence to verifiable performance metrics, such as device efficacy rates and failure thresholds derived from longitudinal data, fostering innovations that systematically improve health outcomes across populations.[14]Interdisciplinary Foundations

Biomedical engineering synthesizes foundational principles from physics, chemistry, mathematics, and computer science to quantitatively address the complexities of biological systems, prioritizing mechanistic understanding over purely descriptive approaches. Physics contributes mechanics to analyze forces and motions in tissues and organs, enabling predictions of structural integrity under load. Chemistry underpins biomaterials design by elucidating molecular interactions at interfaces between synthetic materials and living tissues, such as biocompatibility and degradation kinetics. Mathematics provides tools for abstraction and prediction, including calculus for rate processes and statistics for uncertainty quantification. Computer science supports algorithmic processing of vast datasets from imaging and sensors, as well as computational simulations of multiscale phenomena.[15][16][17] These disciplines converge in core methodologies: mechanics informs biomechanics through stress-strain relationships derived from continuum assumptions, materials science guides implant development via thermodynamic principles of surface energy and corrosion resistance, signal processing employs Fourier transforms and filtering to extract meaningful patterns from noisy physiological data, and control theory applies feedback loops to stabilize systems like homeostasis regulators. This integration allows for causal modeling of physiological dynamics, where ordinary differential equations capture time-dependent interactions, such as ion fluxes in excitable cells or hormone secretion rates, yielding testable predictions of system behavior under perturbation.[18][19][20] Empirical validation remains central, with iterative prototyping using rapid fabrication techniques to test hypotheses against physical prototypes, followed by rigorous clinical trials to assess performance metrics like efficacy and safety in human subjects. This process refutes models through data-driven falsification, as discrepancies between predictions and observations—such as unexpected wear in prototypes or variability in trial outcomes—prompt refinement of underlying assumptions. Regulatory frameworks, including FDA oversight since the 1976 Medical Device Amendments, enforce such validation to ensure devices meet predefined performance criteria based on empirical evidence rather than theoretical consensus alone.[21][22][23]History

Early Foundations (Pre-20th Century to World War II)

The discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen on November 8, 1895, marked a pivotal empirical advancement in non-invasive medical imaging, as cathode rays produced penetrating radiation capable of revealing internal bone structures on photographic plates.[24] This breakthrough stemmed from direct experimentation with vacuum tubes, enabling causal inference about tissue density differences without surgical intervention and laying groundwork for engineering-based diagnostic tools.[25] In the early 20th century, Willem Einthoven developed the first practical electrocardiograph in 1903, utilizing a string galvanometer to quantitatively record the heart's electrical potentials as deflection waves on a photographic medium.[26] This instrument allowed precise measurement of cardiac rhythm abnormalities through empirical waveform analysis, facilitating engineering applications to physiological signal processing and foreshadowing quantitative modeling in biomedicine.[27] World War I's unprecedented scale of injuries, including over 40,000 British amputees, drove mass production of prosthetic limbs using aluminum and leather, emphasizing functional restoration via mechanical design informed by injury mechanics.[28] During World War II, further refinements in prosthetic engineering incorporated causal analysis of biomechanics, with U.S. military efforts yielding improved upper-limb devices for approximately 3,475 amputees, prioritizing empirical fit and mobility.[29] Concurrently, blood transfusion technologies advanced under wartime exigencies; by WWII, dried plasma kits and citrate-glucose solutions enabled field storage and administration, reducing shock mortality through preserved blood components' direct physiological effects.[30] These developments underscored biomedical engineering's origins in pragmatic, evidence-driven responses to trauma, predating formal disciplinary structures.Post-War Emergence (1940s-1960s)

Following World War II, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF), established in 1950, began providing training grants and funding for biomedical research, including bioinstrumentation that adapted wartime electronics and instrumentation for diagnostic and therapeutic applications.[31][32] These efforts catalyzed interdisciplinary work, with the first Conference on Engineering in Medicine and Biology held in 1948, fostering collaboration between engineers and physicians on devices like improved electrocardiographs and early imaging systems.[33] NSF grants specifically supported laboratory construction and equipment for health-related studies, enabling quantitative analysis of biological signals.[34] By the 1950s, initial master's and doctoral programs in medical engineering emerged, emphasizing quantitative modeling of physiological systems through electrical and mechanical principles derived from wartime radar and computing advances.[35] This period saw the formalization of biomedical engineering as a discipline distinct from pure medicine or electrical engineering, with focus on causal mechanisms in bioelectricity and fluid dynamics for health innovations.[36] In the late 1960s, dedicated university departments solidified the field: the University of Virginia initiated biomedical engineering in 1963 with Board approval and full department status by 1967; Case Western Reserve University established its joint engineering-medicine department in 1968; and Johns Hopkins followed suit around the same time, prioritizing bio-modeling for prosthetics and instrumentation.[37][38][36] A pivotal milestone was the 1958 implantation of the first fully implantable cardiac pacemaker in Sweden by surgeon Åke Senning and engineer Rune Elmqvist, which applied pulse generator circuits—rooted in electrical engineering—to restore heart rhythm, demonstrating the potential for engineered devices to sustain life via precise electrical stimulation.[39][40] This innovation highlighted the shift toward reliable, implantable bioinstrumentation, influencing subsequent U.S. developments in arrhythmia management.[41]Modern Expansion (1970s-Present)

The 1970s marked a pivotal expansion in biomedical engineering through the commercialization of advanced imaging technologies, leveraging computational algorithms to reconstruct biological structures from X-ray data. The first computed tomography (CT) scanner was introduced clinically in 1971, enabling non-invasive cross-sectional imaging that revolutionized diagnostics by reducing reliance on exploratory surgery.[42] This physics-driven innovation, rooted in tomographic reconstruction mathematics developed in the 1960s, saw rapid market adoption as manufacturers scaled production for hospitals, with over 20 CT systems installed in the U.S. by 1975.[43] Concurrently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) emerged in the late 1970s, with prototype systems demonstrating human brain scans by 1977; full clinical deployment accelerated in the 1980s as superconducting magnets and Fourier transform algorithms enabled high-resolution soft tissue visualization without ionizing radiation.[44] The 1980s further propelled field growth via device automation and regulatory pathways that facilitated market entry. A landmark was Purdue University's development of the first automated external defibrillator in 1981 by Leslie Geddes and Michael Bourland, which incorporated ECG analysis circuits to detect ventricular fibrillation and deliver shocks autonomously, leading to 36 U.S. patents and widespread adoption in emergency response by the 1990s.[45] FDA approvals streamlined commercialization, shifting focus from bespoke prototypes to standardized, scalable products; this era saw biomedical engineering departments proliferate at universities, training engineers for industry roles in signal processing and biomaterials. Market incentives drove innovations like improved pacemakers and prosthetic limbs, with private investment outpacing federal grants in device sectors by emphasizing iterative prototyping over theoretical modeling. From the 1990s onward, computational biology integrated with engineering, amplifying expansion through genomics and nanotechnology. The Human Genome Project (1990–2003) catalyzed bioinformatics tools for sequence analysis, enabling engineered diagnostics like DNA microarrays for gene expression profiling in cancer detection.[46] Nanotechnology advanced drug delivery systems, with FDA-approved nanoparticle formulations for targeted chemotherapy emerging by 2005, reducing systemic toxicity via surface-engineered particles that exploit enhanced permeability in tumors.[47] These developments underscored market-driven progress, as biotech firms commercialized platforms yielding returns superior to subsidized alternatives in precision medicine. The 2010s integrated artificial intelligence into predictive diagnostics, enhancing computational models for real-time analysis. AI algorithms trained on large imaging datasets improved CT and MRI interpretation accuracy by 10–20% in detecting anomalies like tumors, with convolutional neural networks automating feature extraction.[48] This era's economic scale is evident in NIH-funded biomedical research, which generated $94 billion in U.S. economic activity in fiscal year 2024 through job creation (over 400,000 positions) and downstream innovations, though private sector commercialization amplified impacts via venture-backed startups.[49] Overall, these advances prioritized empirical validation and causal modeling of biological responses, fostering a industry ecosystem where regulatory-approved technologies directly addressed clinical unmet needs.Fundamental Principles

Engineering Applications to Biological Systems

Biomedical engineers apply systems engineering methodologies to physiological systems by representing biological processes as interconnected components with defined inputs, outputs, and regulatory mechanisms, enabling the design of interventions that mimic or augment natural functions.[50] This involves constructing mathematical models based on differential equations to capture dynamic behaviors, such as mass transport or signal propagation in tissues, which support predictive simulations rather than relying solely on observational data.[51] Prioritizing causal inference—identifying mechanistic pathways through techniques like structural equation modeling—over correlative associations ensures that engineered solutions account for underlying physiological drivers, reducing risks of spurious predictions in variable clinical environments.[52] Feedback control principles are central to devices interfacing with regulatory biological loops, as in closed-loop insulin delivery systems that continuously sense blood glucose and modulate infusion rates to maintain euglycemia, emulating pancreatic beta-cell responsiveness.[53] These systems often employ proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers augmented with insulin feedback terms, which adjust dosing based on estimated plasma insulin levels to prevent over-delivery and associated hypoglycemia; clinical evaluations show such modifications improve time-in-range metrics by up to 10-15% compared to open-loop pumps.[54] By incorporating physiologic models of glucose-insulin dynamics, these controls achieve robustness against disturbances like meals or exercise, with real-time algorithms processing sensor data at intervals as short as 5 minutes.[55] Quantitative tools like finite element analysis (FEA) address mechanical interactions by discretizing tissue geometries into meshes and solving for stress-strain distributions under applied loads, informing the configuration of load-bearing implants to minimize fatigue failure.[56] In tissue applications, FEA incorporates hyperelastic material properties to predict deformation responses, as validated against experimental strain data from cadaveric or in vivo tests, enabling designs that distribute stresses below yield thresholds—typically under 1-5 MPa for soft tissues.[57] This method facilitates causal optimization by linking geometric parameters to failure modes, such as stress concentrations leading to implant loosening, prior to fabrication.[58] Scalability from prototypes to deployable systems demands verification through metrics like mean time to failure, often below 1% in long-term cohorts for validated devices, ensuring cost-effective production while preserving causal fidelity in models adapted to manufacturing variances.[59] Empirical data from post-market surveillance, including adverse event rates reported to regulatory bodies, guide iterative refinements, confirming that engineered approximations of biological causality translate to reliable clinical outcomes.[60]Quantitative Modeling and Causal Analysis

Quantitative modeling in biomedical engineering derives primarily from first-principles approaches, grounding simulations in fundamental physical laws such as Newton's equations of motion for mechanical systems and conservation principles for transport phenomena. In biomechanics, for instance, stress-strain relationships in tissues are modeled using Newton's second law () to relate applied forces to deformations, enabling predictions of joint loading under physiological conditions without reliance on empirical fitting alone.[61] This method prioritizes mechanistic understanding over data-driven approximations, as deviations from first-principles can amplify errors in extrapolated scenarios like implant design. For cardiovascular devices, partial differential equations (PDEs) such as the Navier-Stokes equations govern fluid dynamics, describing blood flow velocity and pressure fields: , where is density, velocity, pressure, viscosity, and body forces.[62] Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) implementations solve these numerically to optimize stent geometries or ventricular assist devices, with validations against empirical Doppler ultrasound data confirming shear stress predictions within 10-15% accuracy in idealized arterial models.[63] Such derivations ensure models capture causal pathways, like turbulence-induced endothelial damage, rather than mere statistical correlations from observational flows. Stochastic processes address variability in biological kinetics, particularly drug delivery, where release follows Markov chains or diffusion equations augmented with random walks: the Fokker-Planck equation , modeling concentration evolution under drift and diffusion .[64] Empirical testing via in vitro release assays validates these against deterministic limits, revealing burst effects in nanoparticle carriers that reduce efficacy by up to 30% without accounting for molecular noise.[65] Causal analysis enforces validation through interventional experiments demonstrating direct mechanistic links, rejecting inferences from observational data alone due to confounding variables like comorbidities.[52] In model refinement, do-calculus or structural equation models quantify intervention effects, as in assessing device-induced flow changes on thrombosis risk, where randomized trials confirm causal reductions in wall shear gradients below 4 Pa.[66] This contrasts with black-box machine learning approaches, which, despite predictive accuracy, fail causal scrutiny without underlying mechanistic decomposition, risking unvalidated extrapolations in heterogeneous patient cohorts.[67] Hybrid frameworks integrating causal graphs with AI thus prioritize empirical perturbation tests to affirm model fidelity.[68]Subfields

Biomechanics

Biomechanics applies principles of mechanics to analyze the mechanical behavior of biological tissues and structures, quantifying stresses, strains, and deformations under physiological loads to inform injury prevention and enhance device performance in load-bearing systems.[69] This subfield emphasizes causal relationships between external forces, internal tissue responses, and functional outcomes, such as joint stability and fracture resistance, through empirical measurement and computational simulation.[70] Tissues like bone and cartilage exhibit anisotropic and heterogeneous properties, where mechanical integrity depends on hierarchical structures from molecular to macroscopic scales.[71] Central concepts include tissue viscoelasticity, where soft connective tissues such as ligaments and tendons display time-dependent deformation, combining elastic recovery with viscous dissipation, as evidenced by creep under sustained load and stress relaxation over time.[72] Fracture mechanics extends this to hard tissues like bone, modeling crack initiation and propagation using stress intensity factors and energy release rates to predict failure thresholds under cyclic loading, with empirical data showing bone's toughness derived from collagen-mineral interactions resisting brittle fracture.[73] These properties are strain-rate sensitive, with tendons exhibiting up to 50% higher stiffness at rapid loading rates compared to quasi-static conditions, reflecting adaptive responses to dynamic activities.[74] In orthopedics, finite element analysis (FEA) simulates bone stress distributions to evaluate load transfer and fracture risk, discretizing complex geometries into elements to compute displacements and principal stresses under body-weight equivalents, often validated against cadaveric experiments showing peak femoral stresses exceeding 10 MPa during stance phase.[70] Gait analysis integrates kinematics and kinetics to link ambulatory patterns with tissue loading, revealing that variations in hip moments during walking correlate with implant wear, where sagittal plane moments explain 42-60% of polyethylene wear rates in total hip replacements.[75] Such biomechanical insights have informed designs reducing aseptic loosening risks, with studies demonstrating that patient-specific gait modifications via assistive devices can lower peak joint forces by 20-30%, thereby extending implant longevity beyond baseline 10-year survival rates of approximately 90%.[76][77]Biomaterials

Biomaterials encompass engineered substances designed to interface with biological tissues, prioritizing biocompatibility defined as the capacity to elicit minimal adverse host responses while maintaining functional integrity over time. Selection criteria emphasize material properties such as degradation kinetics, where resorbable polymers hydrolyze at rates matching tissue remodeling (e.g., poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) degrading in 1-6 months via ester bond cleavage), and surface chemistry influencing protein adsorption and subsequent immune activation, including macrophage polarization toward pro-inflammatory phenotypes if hydrophobic surfaces predominate. Empirical data from implantation trials reveal that foreign body reactions, characterized by fibrous encapsulation, correlate with surface topography; nanoscale roughness below 10 nm reduces thrombosis risk in vascular grafts by altering fibrinogen conformation.[78][79] Common classes include metals like titanium alloys (e.g., Ti-6Al-4V), valued for tensile strength exceeding 900 MPa and corrosion resistance via a stable 5-10 nm oxide passivation layer that reforms spontaneously post-scratch in physiological saline, minimizing ion release below 1 ppm even after 10^6 cycles of simulated wear. Ceramics such as alumina or zirconia provide compressive strengths up to 4 GPa with low elastic modulus mismatch to bone (10-20 GPa vs. cortical bone's 15-30 GPa), though brittleness limits load-bearing unless composited; bioactive variants like hydroxyapatite foster apatite layer formation within 7-14 days in simulated body fluid. Polymers range from inert polyurethanes for flexible catheters to degradable polylactic acid, where chain scission yields lactic acid metabolized at 0.1-1 μmol/g tissue daily, but bulk erosion can cause pH drops inducing osteoclastic activity if uncoated.[80][81][82] In vitro cytotoxicity assays, standardized under ISO 10993-5, quantify cell viability via MTT reduction or LDH release after 24-48 hour exposure to material extracts, grading responses from non-cytotoxic (viability >70%) to severe if below 30%, with L929 fibroblasts or ISO-approved lines detecting leachables like residual monomers at concentrations as low as 0.1 μg/mL. In vivo evaluation employs subcutaneous rodent implants for acute inflammation tracking (e.g., neutrophil influx peaking at 24 hours) or ovine femoral models for chronic osseointegration, measuring bone-implant contact ratios via histomorphometry after 12 weeks, where values above 50% indicate successful ankylosis without excessive peri-implant osteolysis. These models reveal causal links, such as surface titanium particles (1-5 μm) eliciting IL-1β mediated resorption if exceeding 0.01 wt% debris.[83][84][85] Recent advances feature stimuli-responsive materials, including pH-sensitive poly(acrylic acid) hydrogels that swell 200-500% at acidic tumor microenvironments (pH 6.5) for triggered release, or thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) polymers exhibiting lower critical solution temperature at 32°C to facilitate cell sheet detachment without enzymatic damage. These enable dynamic adaptation, such as temperature-gated valves in stents modulating permeability from 10^(-6) to 10^(-4) cm/s, grounded in empirical tuning of hydrophilic-hydrophobic balances to minimize chronic inflammation in canine aorta trials.[86][87][88]Biomedical Optics

Biomedical optics encompasses the use of light-based methods to probe, image, and treat biological tissues, exploiting fundamental photon-tissue interactions such as absorption and scattering to achieve high-resolution diagnostics and minimally invasive therapies. Absorption involves photons being captured by molecular chromophores like hemoglobin, water, or melanin, converting optical energy into thermal, fluorescent, or photochemical effects that underpin techniques like photodynamic therapy. Scattering, arising from refractive index mismatches in cellular structures, dominates light propagation in turbid media like tissue, limiting penetration depth to millimeters in the visible and near-infrared spectra while enabling contrast in imaging modalities. These interactions are quantified via metrics like the absorption coefficient (μ_a, in cm⁻¹) and reduced scattering coefficient (μ_s'), which govern the Beer-Lambert law for attenuation and diffusion approximations for deeper propagation.[89] Optical coherence tomography (OCT), a cornerstone technique, employs low-coherence interferometry to generate cross-sectional images with axial resolutions of 1–15 μm and transverse resolutions of 10–20 μm, surpassing ultrasound in superficial tissue visualization. First demonstrated in 1991 by Huang et al. using a Michelson interferometer setup on biological samples, OCT relies on backscattered light phase differences to reconstruct subsurface structures without contact, achieving signal-to-noise ratios exceeding 100 dB in clinical ophthalmic applications.[90] Its micron-scale resolution stems from broadband light sources (e.g., superluminescent diodes at 800–1300 nm), where coherence length inversely scales with bandwidth, enabling real-time in vivo imaging of retinal layers or vascular endothelium.[90] In therapeutic contexts, laser surgery utilizes focused coherent light for precise tissue ablation via photothermal or photochemical mechanisms, with pulse durations tailored to minimize collateral damage—nanosecond pulses for photodisruption in glaucoma treatment or continuous-wave modes for hemostasis in endoscopic procedures. Carbon dioxide lasers at 10.6 μm excel in soft-tissue vaporization due to high water absorption (μ_a ≈ 800 cm⁻¹), while Nd:YAG lasers at 1064 nm penetrate deeper (up to 5–10 mm) for coagulation of vascular lesions, reducing intraoperative blood loss by 50–70% compared to conventional scalpels in documented surgical trials.[91] Diagnostic applications leverage spectroscopic analysis of absorption and scattering spectra to detect biochemical alterations, such as elevated nucleic acid fluorescence in malignant cells. Raman spectroscopy, for instance, identifies vibrational fingerprints shifted by cancer-specific molecular changes, yielding sensitivity and specificity rates of 90–98% in esophageal and colorectal endoscopy when combined with autofluorescence.[92] Fluorescence endoscopy techniques, using exogenous agents like 5-aminolevulinic acid, enhance protoporphyrin IX accumulation in neoplastic tissues, achieving detection sensitivities of 92–97% for dysplasia with specificities of 80–90%, outperforming white-light inspection by revealing subsurface metabolic heterogeneity verifiable through biopsy correlation.[92] These metrics derive from controlled studies emphasizing spectral unmixing to isolate endogenous fluorophores, underscoring optics' role in causal tissue characterization over empirical pattern recognition alone.[93]Tissue and Regenerative Engineering

Tissue and regenerative engineering applies principles of biomedical engineering to fabricate functional tissues and organs by combining scaffolds, cells, and signaling factors to replicate native tissue architecture and promote repair. Scaffolds serve as temporary frameworks that mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM), providing mechanical support, guiding cell adhesion, and facilitating nutrient diffusion while degrading to yield space for regenerated tissue. Biodegradable polymers, such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and polycaprolactone (PCL), are commonly employed due to their tunable degradation rates matching tissue remodeling timelines, typically ranging from weeks to months depending on molecular weight and copolymer ratios.[94][95] These materials incorporate nanoscale topography and biochemical ligands, like RGD peptides, to enhance cell-scaffold interactions and direct differentiation.[96] Stem cell integration enhances regenerative potential by seeding patient-derived or allogeneic cells onto scaffolds to drive tissue-specific morphogenesis. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from bone marrow or adipose tissue are frequently used for their multipotency and immunomodulatory properties, enabling differentiation into lineages such as chondrocytes or osteocytes under scaffold-constrained conditions. In organ repair applications, such as cartilage or urethral reconstruction, scaffolds seeded with MSCs promote ECM deposition and mechanical functionality, with preclinical studies showing up to 80% restoration of native tensile strength in small defects after 12 weeks in vivo.[97] Empirical outcomes prioritize measurable metrics like cell viability (>90% post-seeding) and functional integration over speculative scalability.[98] A key milestone occurred in 2006 when Anthony Atala's team reported the first human clinical trial of tissue-engineered bladders, implanting autologous urothelial and smooth muscle cells grown on collagen-polyglycolic acid (PGA) scaffolds into seven patients aged 4-19 with myelomeningocele. Follow-up data at 22-61 months indicated improved bladder capacity (mean increase of 47 mL) and compliance in responsive patients, with no antigenicity or obstruction, though urodynamic stability varied.[99] This demonstrated feasibility for hollow organ augmentation but highlighted dependency on patient-specific cell sourcing and scaffold biocompatibility. Earlier, skin equivalents using dermal fibroblasts on polymer meshes achieved clinical use for burn coverage by 1981, marking initial empirical success in thin, avascular tissues.[100] Persistent challenges include vascularization deficits in constructs exceeding 200-500 μm thickness, where diffusive oxygen supply limits cell survival, causing central necrosis observed in 70-90% of larger preclinical grafts without engineered vasculature. Clinical trials for complex tissues, such as engineered livers or hearts, report failure rates above 50% due to inadequate perfusion, underscoring causal barriers like endothelial cell misalignment and shear stress intolerance in synthetic vessels. Strategies like co-culturing with endothelial progenitors yield partial microvasculature (densities up to 50 vessels/mm²), but integration into host circulation remains inconsistent, with patency rates below 60% at 3 months post-implantation. These data constrain applications to low-demand repairs, emphasizing the need for quantitative perfusion models over optimistic projections.[101][102][103]Neural Engineering

Neural engineering applies engineering principles to interface electronic devices with the nervous system, enabling the recording of electrophysiological signals such as action potentials and local field potentials to decode neural intent, or the delivery of electrical stimulation to modulate activity. This subfield emphasizes causal mechanisms of neural signaling, where precise timing of action potentials—brief voltage spikes propagating along axons—encodes information through spike rates, temporal patterns, and population synchrony across neuron ensembles. Devices like intracortical microelectrode arrays penetrate cortical tissue to access single-unit activity, facilitating real-time signal processing for applications in restoring lost functions without relying on peripheral pathways.[104][105] A cornerstone technology is the Utah electrode array, a silicon-based microelectrode array developed in the 1980s by Richard Normann at the University of Utah, featuring up to 100 penetrating electrodes, each 1-1.5 mm long, capable of chronic implantation for multi-year recording durations averaging 622 days, with some exceeding 1,000 days. These arrays detect extracellular action potentials with high spatiotemporal resolution, allowing decoding algorithms to map neural firing patterns to motor commands via methods like population vector tuning or Kalman filters that estimate kinematics from spike trains. Neural plasticity underpins decoder efficacy, as synaptic reorganization and cortical remapping—driven by Hebbian-like mechanisms where correlated pre- and post-synaptic activity strengthens connections—enable adaptive recalibration post-implantation, compensating for signal drift or tissue encapsulation.[106][107][108] In brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) for motor restoration, decoded signals drive prosthetic limbs or robotic effectors, bypassing damaged spinal pathways in conditions like tetraplegia. Clinical trials using Utah arrays in human participants have demonstrated decoding accuracies of 70-90% for intended movement directions, with participants achieving cursor control speeds up to 25 bits per minute and prosthetic grasp control in real-time tasks after training periods leveraging plasticity. For instance, long-term implants in multiple subjects have sustained single-neuron yield for over two years, supporting causal inference from neural ensembles to actions without confounding peripheral feedback. These outcomes derive from empirical validation in controlled settings, prioritizing signal-to-noise ratios above 5:1 for reliable spike sorting, though challenges like gliosis-induced impedance rise necessitate material innovations for stability.[109][110][111]Genetic and Pharmaceutical Engineering