Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Supramolecular chemistry

View on WikipediaSupramolecular chemistry is the branch of chemistry concerning chemical systems composed of a discrete numbers of molecules. The strength of the forces responsible for spatial organization of the system ranges from weak intermolecular forces, electrostatic charge, or hydrogen bonding to strong covalent bonding, provided that the electronic coupling strength remains small relative to the energy parameters of the component.[1][2][page needed] While traditional chemistry concentrates on the covalent bond, supramolecular chemistry examines the weaker and reversible non-covalent interactions between molecules.[3] These forces include hydrogen bonding, metal coordination, hydrophobic forces, van der Waals forces, pi–pi interactions and electrostatic effects.[4][5]

Important concepts advanced by supramolecular chemistry include molecular self-assembly, molecular folding, molecular recognition, host–guest chemistry, mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures, and dynamic covalent chemistry.[6] The study of non-covalent interactions is crucial to understanding many biological processes that rely on these forces for structure and function. Biological systems are often the inspiration for supramolecular research.

-

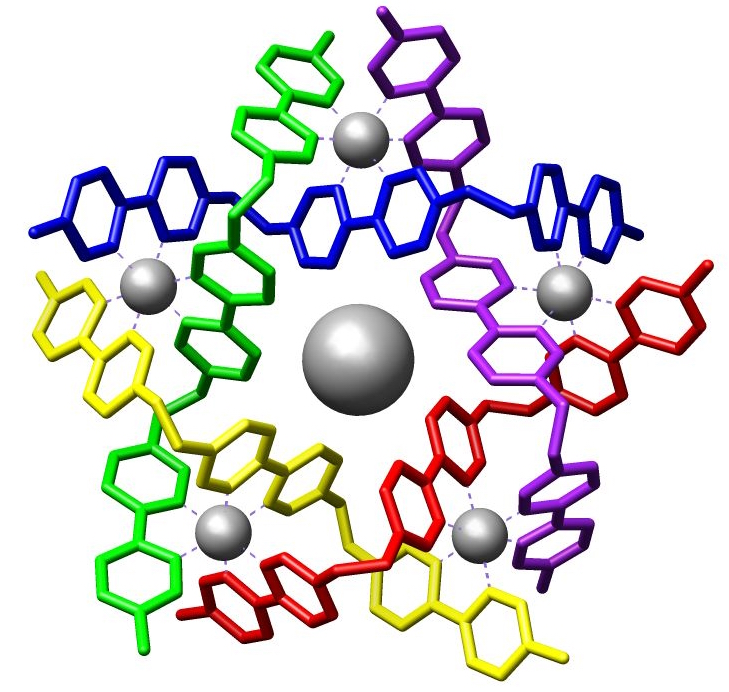

Self-assembly of a circular double helicate[7]

-

Host–guest complex within another host (cucurbituril)[8]

-

An example of a host–guest chemistry[10]

-

Host–guest complex with a p-xylylenediammonium bound within a cucurbituril[11]

-

Two pyrene butyric acids bound within a C-hexylpyrogallol[4]arenes nanocapsule. The side chains of the pyrene butyric acids are omitted.[13]

-

Structure of two isophthalic acids bound to a host molecule through hydrogen bonds[14]

-

Structure of a short peptide L-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala (bacterial cell wall precursor) bound to the antibiotic vancomycin[15]

History

[edit]

The existence of intermolecular forces was first postulated by Johannes Diderik van der Waals in 1873. However, Nobel laureate Hermann Emil Fischer developed supramolecular chemistry's philosophical roots. In 1894,[16] Fischer suggested that enzyme–substrate interactions take the form of a "lock and key", the fundamental principles of molecular recognition and host–guest chemistry. In the early twentieth century non-covalent bonds were understood in gradually more detail, with the hydrogen bond being described by Latimer and Rodebush in 1920.

With the deeper understanding of the non-covalent interactions, for example, the clear elucidation of DNA structure, chemists started to emphasize the importance of non-covalent interactions.[17] In 1967, Charles J. Pedersen discovered crown ethers, which are ring-like structures capable of chelating certain metal ions. Then, in 1969, Jean-Marie Lehn discovered a class of molecules similar to crown ethers, called cryptands. After that, Donald J. Cram synthesized many variations to crown ethers, on top of separate molecules capable of selective interaction with certain chemicals. The three scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1987 for "development and use of molecules with structure-specific interactions of high selectivity".[18] In 2016, Bernard L. Feringa, Sir J. Fraser Stoddart, and Jean-Pierre Sauvage were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, "for the design and synthesis of molecular machines".[19]

The term supermolecule (or supramolecule) was introduced by Karl Lothar Wolf et al. (Übermoleküle) in 1937 to describe hydrogen-bonded acetic acid dimers.[20][21] The term supermolecule is also used in biochemistry to describe complexes of biomolecules, such as peptides and oligonucleotides composed of multiple strands.[22]

Eventually, chemists applied these concepts to synthetic systems. One breakthrough came in the 1960s with the synthesis of the crown ethers by Charles J. Pedersen. Following this work, other researchers such as Donald J. Cram, Jean-Marie Lehn and Fritz Vögtle reported a variety of three-dimensional receptors, and throughout the 1980s research in the area gathered a rapid pace with concepts such as mechanically interlocked molecular architectures emerging.

The influence of supramolecular chemistry was established by the 1987 Nobel Prize for Chemistry which was awarded to Donald J. Cram, Jean-Marie Lehn, and Charles J. Pedersen in recognition of their work in this area.[23] The development of selective "host–guest" complexes in particular, in which a host molecule recognizes and selectively binds a certain guest, was cited as an important contribution.

Concepts

[edit]

Molecular self-assembly

[edit]Molecular self-assembly is the construction of systems without guidance or management from an outside source (other than to provide a suitable environment). The molecules are directed to assemble through non-covalent interactions. Self-assembly may be subdivided into intermolecular self-assembly (to form a supramolecular assembly), and intramolecular self-assembly (or folding as demonstrated by foldamers and polypeptides). Molecular self-assembly also allows the construction of larger structures such as micelles, membranes, vesicles, liquid crystals, and is important to crystal engineering.[24]

Molecular recognition and complexation

[edit]Molecular recognition is the specific binding of a guest molecule to a complementary host molecule to form a host–guest complex. Often, the definition of which species is the "host" and which is the "guest" is arbitrary. The molecules are able to identify each other using non-covalent interactions. Key applications of this field are the construction of molecular sensors and catalysis.[25][26][27][28]

Template-directed synthesis

[edit]Molecular recognition and self-assembly may be used with reactive species in order to pre-organize a system for a chemical reaction (to form one or more covalent bonds). It may be considered a special case of supramolecular catalysis. Non-covalent bonds between the reactants and a "template" hold the reactive sites of the reactants close together, facilitating the desired chemistry. This technique is particularly useful for situations where the desired reaction conformation is thermodynamically or kinetically unlikely, such as in the preparation of large macrocycles. This pre-organization also serves purposes such as minimizing side reactions, lowering the activation energy of the reaction, and producing desired stereochemistry. After the reaction has taken place, the template may remain in place, be forcibly removed, or may be "automatically" decomplexed on account of the different recognition properties of the reaction product. The template may be as simple as a single metal ion or may be extremely complex.[citation needed]

Mechanically interlocked molecular architectures

[edit]Mechanically interlocked molecular architectures consist of molecules that are linked only as a consequence of their topology. Some non-covalent interactions may exist between the different components (often those that were used in the construction of the system), but covalent bonds do not. Supramolecular chemistry, and template-directed synthesis in particular, is key to the efficient synthesis of the compounds. Examples of mechanically interlocked molecular architectures include catenanes, rotaxanes, molecular knots, molecular Borromean rings,[29] 2D [c2]daisy chain polymer[30] and ravels.[31]

Dynamic covalent chemistry

[edit]In dynamic covalent chemistry covalent bonds are broken and formed in a reversible reaction under thermodynamic control. While covalent bonds are key to the process, the system is directed by non-covalent forces to form the lowest energy structures.[32]

Biomimetics

[edit]Many synthetic supramolecular systems are designed to copy functions of biological systems. These biomimetic architectures can be used to learn about both the biological model and the synthetic implementation. Examples include photoelectrochemical systems, catalytic systems, protein design and self-replication.[33]

Imprinting

[edit]Molecular imprinting describes a process by which a host is constructed from small molecules using a suitable molecular species as a template. After construction, the template is removed leaving only the host. The template for host construction may be subtly different from the guest that the finished host binds to. In its simplest form, imprinting uses only steric interactions, but more complex systems also incorporate hydrogen bonding and other interactions to improve binding strength and specificity.[34]

Molecular machinery

[edit]Molecular machines are molecules or molecular assemblies that can perform functions such as linear or rotational movement, switching, and entrapment. These devices exist at the boundary between supramolecular chemistry and nanotechnology, and prototypes have been demonstrated using supramolecular concepts.[35] Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir J. Fraser Stoddart and Bernard L. Feringa shared the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the 'design and synthesis of molecular machines'.[36]

Building blocks

[edit]Supramolecular systems are rarely designed from first principles. Rather, chemists have a range of well-studied structural and functional building blocks that they are able to use to build up larger functional architectures. Many of these exist as whole families of similar units, from which the analog with the exact desired properties can be chosen.

Synthetic recognition motifs

[edit]- The pi-pi charge-transfer interactions of bipyridinium with dioxyarenes or diaminoarenes have been used extensively for the construction of mechanically interlocked systems and in crystal engineering.

- The use of crown ether binding with metal or ammonium cations is ubiquitous in supramolecular chemistry.

- The formation of carboxylic acid dimers and other simple hydrogen bonding interactions.

- The complexation of bipyridines or terpyridines with ruthenium, silver or other metal ions is of great utility in the construction of complex architectures of many individual molecules.

- The complexation of porphyrins or phthalocyanines around metal ions gives access to catalytic, photochemical and electrochemical properties in addition to the complexation itself. These units are used a great deal by nature.

Macrocycles

[edit]Macrocycles are very useful in supramolecular chemistry, as they provide whole cavities that can completely surround guest molecules and may be chemically modified to fine-tune their properties.

- Cyclodextrins, calixarenes, cucurbiturils and crown ethers are readily synthesized in large quantities, and are therefore convenient for use in supramolecular systems.

- More complex cyclophanes, and cryptands can be synthesised to provide more tailored recognition properties.

- Supramolecular metallocycles are macrocyclic aggregates with metal ions in the ring, often formed from angular and linear modules.[37] Common metallocycle shapes in these types of applications include triangles, squares, and pentagons, each bearing functional groups that connect the pieces via "self-assembly."[38]

- Metallacrowns are metallomacrocycles generated via a similar self-assembly approach from fused chelate-rings.

Structural units

[edit]Many supramolecular systems require their components to have suitable spacing and conformations relative to each other, and therefore easily employed structural units are required.[39]

- Commonly used spacers and connecting groups include polyether chains, biphenyls and terphenyls, and simple alkyl chains. The chemistry for creating and connecting these units is very well understood.

- nanoparticles, nanorods, fullerenes and dendrimers offer nanometer-sized structure and encapsulation units.

- Surfaces can be used as scaffolds for the construction of complex systems and also for interfacing electrochemical systems with electrodes. Regular surfaces can be used for the construction of self-assembled monolayers and multilayers.

- The understanding of intermolecular interactions in solids has undergone a major renaissance via inputs from different experimental and computational methods in the last decade. This includes high-pressure studies in solids and "in situ" crystallization of compounds which are liquids at room temperature along with the use of electron density analysis, crystal structure prediction and DFT calculations in solid state to enable a quantitative understanding of the nature, energetics and topological properties associated with such interactions in crystals.[40]

Photo-chemically and electro-chemically active units

[edit]- Porphyrins, and phthalocyanines have highly tunable photochemical and electrochemical activity as well as the potential to form complexes.

- Photochromic and photoisomerizable groups can change their shapes and properties, including binding properties, upon exposure to light.

- Tetrathiafulvalene (TTF) and quinones have multiple stable oxidation states, and therefore can be used in redox reactions and electrochemistry.

- Other units, such as benzidine derivatives, viologens, and fullerenes, are useful in supramolecular electrochemical devices.

Biologically-derived units

[edit]- The extremely strong complexation between avidin and biotin is instrumental in blood clotting, and has been used as the recognition motif to construct synthetic systems.

- The binding of enzymes with their cofactors has been used as a route to produce modified enzymes, electrically contacted enzymes, and even photoswitchable enzymes.

- DNA has been used both as a structural and as a functional unit in synthetic supramolecular systems.

Applications

[edit]Materials technology

[edit]Supramolecular chemistry has found many applications,[41] in particular molecular self-assembly processes have been applied to the development of new materials. Large structures can be readily accessed using bottom-up synthesis as they are composed of small molecules requiring fewer steps to synthesize. Thus most of the bottom-up approaches to nanotechnology are based on supramolecular chemistry.[42] This approach is applied in the synthesis of metallogels, one-dimensional nanostructured materials formed from low molecular weight gelators and metal ions.[43] Many smart materials[44] are based on molecular recognition.[45]

Catalysis

[edit]A major application of supramolecular chemistry is the design and understanding of catalysts and catalysis. Non-covalent interactions influence the binding reactants.[46]

Medicine

[edit]Design based on supramolecular chemistry has led to numerous applications in the creation of functional biomaterials and therapeutics.[47] Supramolecular biomaterials afford a number of modular and generalizable platforms with tunable mechanical, chemical and biological properties. These include systems based on supramolecular assembly of peptides, host–guest macrocycles, high-affinity hydrogen bonding, and metal–ligand interactions.

A supramolecular approach has been used extensively to create artificial ion channels for the transport of sodium and potassium ions into and out of cells.[48]

Supramolecular chemistry is also important to the development of new pharmaceutical therapies by understanding the interactions at a drug binding site. The area of drug delivery has also made critical advances as a result of supramolecular chemistry providing encapsulation and targeted release mechanisms.[49] In addition, supramolecular systems have been designed to disrupt protein–protein interactions that are important to cellular function.[50]

Data storage and processing

[edit]Supramolecular chemistry has been used to demonstrate computation functions on a molecular scale. In many cases, photonic or chemical signals have been used in these components, but electrical interfacing of these units has also been shown by supramolecular signal transduction devices. Data storage has been accomplished by the use of molecular switches with photochromic and photoisomerizable units, by electrochromic and redox-switchable units, and even by molecular motion. Synthetic molecular logic gates have been demonstrated on a conceptual level. Even full-scale computations have been achieved by semi-synthetic DNA computers.

See also

[edit]Reading

[edit]- Cook, T. R.; Zheng, Y.; Stang, P. J. (2013). "Metal-organic frameworks and self-assembled supramolecular coordination complexes: Comparing and contrasting the design, synthesis, and functionality of metal-organic materials". Chem. Rev. 113 (1): 734–77. doi:10.1021/cr3002824. PMC 3764682. PMID 23121121.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Desiraju, G. R. (2013). "Crystal engineering: From molecule to crystal". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (27): 9952–67. Bibcode:2013JAChS.135.9952D. doi:10.1021/ja403264c. PMID 23750552.

- Seto, C. T.; Whitesides, G. M. (1993). "Molecular self-assembly through hydrogen bonding: Supramolecular aggregates based on the cyanuric acid-melamine lattice". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115 (3): 905–916. Bibcode:1993JAChS.115..905S. doi:10.1021/ja00056a014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

[edit]- ^ Lehn, J. (1993). "Supramolecular Chemistry". Science. 260 (5115): 1762–23. Bibcode:1993Sci...260.1762L. doi:10.1126/science.8511582. PMID 8511582.

- ^ Lehn, J. (1995). Supramolecular Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-29311-7.

- ^ Schneider, H. (2009). "Binding Mechanisms in Supramolecular Complexes". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 48 (22): 3924–77. doi:10.1002/anie.200802947. PMID 19415701.

- ^ Biedermann, F.; Schneider, H.J. (2016). "Experimental Binding Energies in Supramolecular Complexes". Chem. Rev. 116 (9): 5216–5300. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00583. PMID 27136957.

- ^ Steed, Jonathan W.; Atwood, Jerry L. (2009). Supramolecular Chemistry (2nd ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470740880. ISBN 978-0-470-51234-0.

- ^ Oshovsky, G. V.; Reinhoudt, D. N.; Verboom, W. (2007). "Supramolecular Chemistry in Water" (PDF). Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 46 (14): 2366–93. doi:10.1002/anie.200602815. PMID 17370285.

- ^ Hasenknopf, B.; Lehn, J. M.; Kneisel, B. O.; Baum, G.; Fenske, D. (1996). "Self-Assembly of a Circular Double Helicate". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 35 (16): 1838–1840. doi:10.1002/anie.199618381.

- ^ Day, A. I.; Blanch, R. J.; Arnold, A. P.; Lorenzo, S.; Lewis, G. R.; Dance, I. (2002). "A Cucurbituril-Based Gyroscane: A New Supramolecular Form". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 41 (2): 275–7. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020118)41:2<275::AID-ANIE275>3.0.CO;2-M. PMID 12491407.

- ^ Bravo, J. A.; Raymo, F. I. M.; Stoddart, J. F.; White, A. J. P.; Williams, D. J. (1998). "High Yielding Template-Directed Syntheses of [2]Rotaxanes". European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1998 (11): 2565–2571. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0690(199811)1998:11<2565::AID-EJOC2565>3.0.CO;2-8.

- ^ Anderson, S.; Anderson, H. L.; Bashall, A.; McPartlin, M.; Sanders, J. K. M. (1995). "Assembly and Crystal Structure of a Photoactive Array of Five Porphyrins". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 34 (10): 1096–1099. doi:10.1002/anie.199510961.

- ^ Freeman, W. A. (1984). "Structures of the p-xylylenediammonium chloride and calcium hydrogensulfate adducts of the cavitand 'cucurbituril', C36H36N24O12". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 40 (4): 382–387. Bibcode:1984AcCrB..40..382F. doi:10.1107/S0108768184002354.

- ^ Schmitt, J. L.; Stadler, A. M.; Kyritsakas, N.; Lehn, J. M. (2003). "Helicity-Encoded Molecular Strands: Efficient Access by the Hydrazone Route and Structural Features". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 86 (5): 1598–1624. doi:10.1002/hlca.200390137.

- ^ Dalgarno, S. J.; Tucker, S. A.; Bassil, D. B.; Atwood, J. L. (2005). "Fluorescent Guest Molecules Report Ordered Inner Phase of Host Capsules in Solution". Science. 309 (5743): 2037–9. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.2037D. doi:10.1126/science.1116579. PMID 16179474. S2CID 41468421.

- ^ Bielawski C, Chen Y, Zhang P, Prest P, Moore JS (1998). "A modular approach to constructing multi-site receptors for isophthalic acid". Chemical Communications (12): 1313–4. doi:10.1039/a707262g.

- ^ Knox JR, Pratt RF (July 1990). "Different modes of vancomycin and D-alanyl-D-alanine peptidase binding to cell wall peptide and a possible role for the vancomycin resistance protein". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 34 (7): 1342–1347. doi:10.1128/AAC.34.7.1342. PMC 175978. PMID 2386365.

- ^ Fischer, E. (1894). "Einfluss der Configuration auf die Wirkung der Enzyme". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 27 (3): 2985–2993. doi:10.1002/cber.18940270364.

- ^ "Supramolecular chemistry", Wikipedia, 2023-01-25, retrieved 2023-02-15

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1987". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2023-02-15.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2016". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2023-02-15.

- ^ Wolf, Κ. L.; Frahm, H.; Harms, H. (1937-01-01). "Über den Ordnungszustand der Moleküle in Flüssigkeiten" [The State of Arrangement of Molecules in Liquids]. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie (in German). 36B (1). Walter de Gruyter GmbH: 237-287. doi:10.1515/zpch-1937-3618. ISSN 2196-7156.

- ^ Historical Remarks on Supramolecular Chemistry – PDF (16 pg. paper)

- ^ Lehninger, Albert L. (1966). "Supramolecular organization of enzyme and membrane systems". Die Naturwissenschaften. 53 (3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 57–63. Bibcode:1966NW.....53...57L. doi:10.1007/bf00594748. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 5983868.

- ^ Schmeck, Harold M. Jr. (October 15, 1987) "Chemistry and Physics Nobels Hail Discoveries on Life and Superconductors; Three Share Prize for Synthesis of Vital Enzymes". New York Times

- ^ Ariga, K.; Hill, J. P.; Lee, M. V.; Vinu, A.; Charvet, R.; Acharya, S. (2008). "Challenges and breakthroughs in recent research on self-assembly". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (1) 014109. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a4109A. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/1/014109. PMC 5099804. PMID 27877935.

- ^ Kurth, D. G. (2008). "Metallo-supramolecular modules as a paradigm for materials science". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (1) 014103. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a4103G. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/1/014103. PMC 5099798. PMID 27877929.

- ^ Daze, K. (2012). "Supramolecular hosts that recognize methyllysines and disrupt the interaction between a modified histone tail and its epigenetic reader protein". Chemical Science. 3 (9): 2695. doi:10.1039/C2SC20583A.

- ^ Bureekaew, S.; Shimomura, S.; Kitagawa, S. (2008). "Chemistry and application of flexible porous coordination polymers". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (1) 014108. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a4108B. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/1/014108. PMC 5099803. PMID 27877934.

- ^ Lehn, J. M. (1990). "Perspectives in Supramolecular Chemistry—From Molecular Recognition towards Molecular Information Processing and Self-Organization". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 29 (11): 1304–1319. doi:10.1002/anie.199013041.

- ^ Ikeda, T.; Stoddart, J. F. (2008). "Electrochromic materials using mechanically interlocked molecules". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (1) 014104. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a4104I. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/1/014104. PMC 5099799. PMID 27877930.

- ^ Tang, Z.-B.; Bian, L.; Miao, X.; Gao, H.; Liu, L.; Jiang, Q.; Sheng, D.; Xu, L.; Sue, A. C.-H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Z. C. (2025). "Synthesis of a crystalline two-dimensional [c2]daisy chain honeycomb network". Nature Synthesis. 4. doi:10.1038/s44160-025-00791-x.

- ^ Li, F.; Clegg, J. K.; Lindoy, L. F.; MacQuart, R. B.; Meehan, G. V. (2011). "Metallosupramolecular self-assembly of a universal 3-ravel". Nature Communications. 2 205. Bibcode:2011NatCo...2..205L. doi:10.1038/ncomms1208. PMID 21343923.

- ^ Rowan, S. J.; Cantrill, S. J.; Cousins, G. R. L.; Sanders, J. K. M.; Stoddart, J. F. (2002). "Dynamic Covalent Chemistry". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 41 (6): 898–952. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020315)41:6<898::AID-ANIE898>3.0.CO;2-E. PMID 12491278.

- ^ Zhang, S. (2003). "Fabrication of novel biomaterials through molecular self-assembly". Nature Biotechnology. 21 (10): 1171–8. doi:10.1038/nbt874. PMID 14520402. S2CID 54485012.

- ^ Dickert, F. (1999). "Molecular imprinting in chemical sensing". TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 18 (3): 192–199. doi:10.1016/S0165-9936(98)00123-X.

- ^ Balzani, V.; Gómez-López, M.; Stoddart, J. F. (1998). "Molecular Machines". Accounts of Chemical Research. 31 (7): 405–414. doi:10.1021/ar970340y.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2016". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Functional Metallosupramolecular Materials, Editors: John George Hardy, Felix H Schacher, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge 2015, https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/ebook/978-1-78262-267-3

- ^ Lee, S. J.; Lin, W. (2008). "Chiral Metallocycles: Rational Synthesis and Novel Applications". Accounts of Chemical Research. 41 (4): 521–37. doi:10.1021/ar700216n. PMID 18271561.

- ^ Atwood, J. L.; Gokel, George W.; Barbour, Leonard J. (2017-06-22). Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry II. Amsterdam, Netherlands. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-12-803199-5. OCLC 992802408.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Chopra, Deepak, Royal Society of Chemistry (2019). Understanding intermolecular interactions in the solid state: approaches and techniques. London; Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-78801-079-5. OCLC 1103809341.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schneider, H.-J. ( Ed.) (2012) Applications of Supramolecular Chemistry, CRC Press Taylor & Francis Boca Raton etc, [1]

- ^ Gale, P.A. and Steed, J.W. (eds.) (2012) Supramolecular Chemistry: From Molecules to Nanomaterials. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-74640-0

- ^ Picci, Giacomo; Caltagirone, Claudia; Garau, Alessandra; Lippolis, Vito; Milia, Jessica; Steed, Jonathan W. (2023-10-01). "Metal-based gels: Synthesis, properties, and applications". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 492 215225. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215225. ISSN 0010-8545.

- ^ Smart Materials Book Series, Royal Soc. Chem. Cambridge UK . http://pubs.rsc.org/bookshop/collections/series?issn=2046-0066

- ^ Chemoresponsive Materials /Stimulation by Chemical and Biological Signals, Schneider, H.-J. ; Ed:, (2015) The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge https://dx.doi.org/10.1039/9781782622420

- ^ Meeuwissen, J.; Reek, J. N. H. (2010). "Supramolecular catalysis beyond enzyme mimics". Nat. Chem. 2 (8): 615–21. Bibcode:2010NatCh...2..615M. doi:10.1038/nchem.744. PMID 20651721.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Webber, Matthew J.; Appel, Eric A.; Meijer, E. W.; Langer, Robert (18 December 2015). "Supramolecular biomaterials". Nature Materials. 15 (1): 13–26. Bibcode:2016NatMa..15...13W. doi:10.1038/nmat4474. PMID 26681596.

- ^ Rodríguez-Vázquez, Nuria; Fuertes, Alberto; Amorín, Manuel; Granja, Juan R. (2016). "Chapter 14. Bioinspired Artificial Sodium and Potassium Ion Channels". In Sigel, Astrid; Sigel, Helmut; Sigel, Roland K.O. (eds.). The Alkali Metal Ions: Their Role in Life. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 16. Springer. pp. 485–556. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-21756-7_14. ISBN 978-3-319-21755-0. PMID 26860310.

- ^ Smart Materials for Drug Delivery: Complete Set (2013) Royal Soc. Chem. Cambridge UK http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/ebook/9781849735520

- ^ Bertrand, N.; Gauthier, M. A.; Bouvet, C. L.; Moreau, P.; Petitjean, A.; Leroux, J. C.; Leblond, J. (2011). "New pharmaceutical applications for macromolecular binders" (PDF). Journal of Controlled Release. 155 (2): 200–10. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.04.027. PMID 21571017. S2CID 41385952.

External links

[edit]- 2D and 3D Models of Dodecahedrane and Cuneane Assemblies

- Supramolecular Chemistry and Supramolecular Chemistry II – Thematic Series in the Open Access Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry

Supramolecular chemistry

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Principles

Supramolecular chemistry was defined by Jean-Marie Lehn in 1978 as the "chemistry of the intermolecular bond," in contrast to the covalent bonding that defines traditional molecular chemistry. This field examines the structures and functions of entities formed by the association of two or more chemical species through non-covalent interactions, extending chemical organization beyond the single molecule. Central to supramolecular chemistry are principles such as reversibility, which arises from the labile nature of non-covalent bonds allowing dynamic formation and dissociation of complexes; cooperativity, where initial binding events enhance subsequent interactions; and multiplicity, involving numerous simultaneous interactions that stabilize organized architectures. These principles facilitate the hierarchical organization of matter, progressing from discrete supermolecules to larger assemblies and eventually macroscopic structures.[1] The driving forces in supramolecular systems encompass hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking, hydrophobic effects, van der Waals interactions, and electrostatic forces. Electrostatic interactions, governed by Coulomb's law, exemplify the directional nature of these bonds: where is the electrostatic force, is the Coulomb constant, and are the interacting charges, and is the interatomic distance.[4] In distinction from conventional chemistry's focus on robust covalent linkages, supramolecular chemistry leverages these weak, reversible, and often directional non-covalent interactions to enable adaptive and self-correcting behaviors in molecular ensembles.[1]Scope and Importance

Supramolecular chemistry encompasses the design, synthesis, and study of molecular entities and assemblies formed through non-covalent interactions, extending beyond traditional covalent bonding to include host-guest chemistry—where receptor molecules selectively bind guests in cavities or channels—crystal engineering for the rational construction of solid-state architectures, and nanoscale assemblies such as coordination cages, networks, and porous frameworks.[5][6] This scope interfaces with organic chemistry via synthetic molecular recognition motifs, inorganic chemistry through metal-organic frameworks and coordination-driven self-assembly, physical chemistry in analyzing interaction thermodynamics and kinetics, and biological chemistry by replicating natural non-covalent processes like antigen-antibody binding.[7][5] The field's importance stems from its capacity to create adaptive materials that dynamically reorganize in response to stimuli, enabling functionalities unattainable with rigid covalent structures, and to mimic biological processes such as allosteric regulation in proteins or self-sorting in cellular compartments.[7] In sustainability efforts, supramolecular strategies facilitate the development of recyclable polymers, exemplified by shear-thinning supramolecular materials that disassemble under stress for easy reprocessing, thereby reducing waste in plastics production.[5] These approaches prioritize conceptual innovation over exhaustive enumeration, focusing on reversible bonding to enhance material lifespan and environmental compatibility.[5] Interdisciplinarily, supramolecular chemistry bridges to nanotechnology for fabricating responsive nanostructures like actuators and sensors, to green chemistry via low-waste templated syntheses and solvent alternatives, and to systems chemistry where collective behaviors emerge from simple interaction rules, fostering complex adaptive systems.[7][5] Post-2020, the discipline has expanded rapidly, with translational advances in precision medicine through selective molecular sensors and in AI-driven design that employs machine learning to predict and optimize assembly motifs, as evidenced by comprehensive reviews spanning 2021–2025.[5] Societally, supramolecular chemistry contributes to global challenges by enabling advanced energy storage solutions, such as flexible lithium-ion batteries with over 2700% extensibility for wearable devices and hydrogen organic frameworks achieving 53.7 g L⁻¹ uptake, alongside environmental remediation techniques like cyclodextrin-based adsorbents for PFAS removal from water.[5] This potential for scalable, impactful technologies highlights the field's role in fostering sustainable innovation across energy and pollution control domains.[5]Historical Development

Early Foundations

The foundations of supramolecular chemistry can be traced to late 19th-century concepts in biochemistry and organic chemistry, particularly Emil Fischer's proposal of the "lock-and-key" model for enzyme-substrate interactions. In 1894, Fischer suggested that enzymes act as rigid templates that precisely match the shape and chemical features of their substrates, enabling specific binding and catalysis, much like a key fitting into a lock. This analogy emphasized the role of complementary spatial and chemical arrangements in molecular recognition, laying an early conceptual groundwork for understanding non-covalent associations beyond simple covalent bonds. In the early to mid-20th century, advances in structural biology and crystallography further illuminated the importance of weak intermolecular forces. Linus Pauling's investigations from the 1930s onward highlighted hydrogen bonding as a critical stabilizing force in protein structures; collaborating with Alfred Mirsky, he demonstrated that protein denaturation involves the disruption of these bonds between amino acid side chains, preserving the native folded configuration through such interactions. Pauling's later work in the 1950s, including the elucidation of the alpha-helix motif in polypeptides, underscored how hydrogen bonds dictate secondary structures in biomolecules. Concurrently, Kathleen Lonsdale's crystallographic studies provided insights into molecular packing in crystals; her 1929 analysis of hexamethylbenzene confirmed the planarity of the benzene ring and revealed systematic intermolecular arrangements governed by van der Waals forces and symmetry, influencing early notions of designed crystal architectures. Mid-20th-century research on inclusion phenomena also contributed precursor ideas, with chemists exploring compounds where guest molecules are trapped within host lattices without covalent linkages. In the 1930s, studies on clathrate hydrates, such as E. G. Hammerschmidt's examination of gas hydrates forming in pipelines, revealed how water cages encapsulate small molecules like methane through hydrogen-bonded networks, explaining unexpected solidification under moderate conditions. These findings paralleled earlier work on organic inclusion compounds, demonstrating selective entrapment based on size and shape complementarity. Additionally, Alfred Werner's coordination theory from the early 1900s, for which he received the 1913 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, introduced the concept of secondary valence spheres around metal ions, where ligands coordinate via non-covalent-like interactions, influencing later views of multi-point binding in supramolecular assemblies.[8] Despite these developments, early supramolecular concepts remained largely descriptive and biologically or crystallographically oriented, lacking a deliberate synthetic approach to designing molecules for controlled non-covalent interactions.Key Milestones and Nobel Recognition

In 1967, Charles J. Pedersen at DuPont discovered crown ethers, the first synthetic macrocyclic hosts capable of selectively binding alkali metal ions through non-covalent interactions, marking a pivotal advancement in host-guest chemistry. This serendipitous finding arose during investigations into metal ion complexation for catalytic purposes and demonstrated how cyclic polyethers could encapsulate cations like potassium in their ring structures, influencing solubility and reactivity.[9] Pedersen's work laid the groundwork for designing molecules with structure-specific binding, inspiring further synthetic efforts in the field. During the 1970s, Donald J. Cram at UCLA advanced the field by developing spherands and cavitands, rigid, preorganized hosts that achieved exceptionally high binding affinities for guest species through precise geometric complementarity.[10] Spherands, introduced around 1979 but conceptualized earlier in the decade, featured enforced cavities that selectively bound small ions like lithium with association constants exceeding 10^15 M^-1, far surpassing earlier systems due to minimal enthalpic penalties upon complexation.[11] Cavitands, bowl-shaped molecules, extended this precision to larger guests, enabling applications in molecular recognition and separation.[12] Cram's contributions emphasized the principle of preorganization, where host rigidity enhances binding efficiency. Starting in 1968, Jean-Marie Lehn in Strasbourg introduced cryptands, three-dimensional polycyclic ligands that provided even greater selectivity and stability for metal ion encapsulation compared to crown ethers, with binding constants up to 10^10 M^-1 for potassium.[1] Lehn's cryptands, synthesized via templated assembly, exemplified multinuclear coordination and spurred the evolution of supramolecular design. In 1978, Lehn coined the term "supramolecular chemistry" to describe the chemistry of intermolecular associations beyond covalent bonds, formalizing the discipline in a seminal review that highlighted its scope from molecular recognition to self-organization. The groundbreaking work of Pedersen, Cram, and Lehn culminated in the 1987 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded jointly for their development and use of molecules with highly selective structure-specific interactions of complementary substances.[2] The Nobel committee recognized how their synthetic hosts revolutionized understanding of non-covalent forces, enabling tailored molecular assemblies with implications for catalysis, transport, and information processing. Following the 1987 award, the field expanded in the 1990s with the synthesis of rotaxanes and catenanes by J. Fraser Stoddart and collaborators, mechanically interlocked structures where rings thread onto axles, stabilized by non-covalent templates and stoppers.[13] Stoddart's template-directed approaches yielded functional rotaxanes for molecular machines, such as shuttles responsive to redox stimuli.[14] Concurrently, supramolecular polymers emerged, pioneered by Lehn in 1990 through reversible hydrogen-bonding networks that formed linear chains with dynamic properties unlike traditional covalent polymers.[15] Stoddart and others extended this to polyrotaxanes, incorporating mechanical bonds for enhanced mechanical strength and responsiveness.[16] In the 2020s, data-driven characterization techniques have become a key milestone, integrating machine learning and computational modeling to analyze complex supramolecular assemblies in solution, addressing challenges in structural elucidation beyond crystallography.[17] These approaches, such as AI-assisted interpretation of NMR and scattering data, enable predictive design of self-assembled systems with improved accuracy for degree of polymerization and dynamics.Fundamental Concepts

Non-Covalent Interactions

Non-covalent interactions form the foundational weak forces driving supramolecular assembly, encompassing hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, π-π stacking, hydrophobic effects, and van der Waals forces. Hydrogen bonding arises from the attraction between a hydrogen atom covalently bound to an electronegative atom (such as nitrogen, oxygen, or fluorine) and another electronegative atom, with typical strengths ranging from 2 to 10 kcal/mol in neutral systems, though stronger variants up to 20-30 kcal/mol occur in charged or multiple H-bond arrays.[18] The energy of hydrogen bonds is proportional to dipole-dipole interactions, often described as , where represents dipole moments, the distance, and the angle, emphasizing their directional nature.[18] Ionic interactions involve electrostatic attractions between charged species, exhibiting bond energies of 5-50 kcal/mol depending on ion separation and charge magnitude.[19] π-π stacking occurs between aromatic rings through overlapping π-electron clouds, with energies typically 2-5 kcal/mol, while van der Waals forces, primarily dispersion interactions, contribute 0.5-2 kcal/mol per contact.[18] Hydrophobic effects, entropy-driven by the release of ordered water molecules around non-polar groups, provide effective stabilization of 1-5 kcal/mol in aqueous environments.[20] Quantitative aspects of these interactions highlight their directionality and potential for cooperativity, which enhance binding efficiency in supramolecular systems. Hydrogen bonds exhibit strong directionality, preferring linear geometries with donor-hydrogen-acceptor angles near 180°, optimizing orbital overlap and maximizing strength.[21] Cooperativity, exemplified by the chelate effect, arises in multi-site binding where simultaneous interactions amplify overall stability; for instance, bidentate ligands form rings that increase association constants by factors of 10^2 to 10^4 compared to monodentate equivalents, driven by favorable entropy from fewer free molecules in solution.[22] Ionic and π-π interactions show moderate directionality, with optimal geometries aligning charges or π-orbitals, while van der Waals and hydrophobic effects are more isotropic but cumulative in extended assemblies.[18] Bond energies vary with distance, typically following inverse power laws (e.g., for dispersion), underscoring the need for precise molecular design to achieve desired affinities.[19] The role of non-covalent interactions differs markedly between solution and solid states, largely due to solvent modulation of their strengths. In solution, polar solvents with high dielectric constants (e.g., water at ε ≈ 80) screen electrostatic and ionic interactions, reducing their effective energies by up to 50-70% compared to vacuum or non-polar media, while hydrophobic effects dominate in aqueous environments.[23] In the solid state, low-dielectric surroundings (ε ≈ 2-4) enhance all interactions, enabling denser packing and higher thermal stability without solvent competition.[23] This solvent dependence influences assembly pathways, with protic solvents disrupting hydrogen bonds via competitive solvation, whereas aprotic ones preserve them.[24] Experimental probes such as NMR and IR spectroscopy provide direct insights into interaction strengths and dynamics. NMR detects chemical shift perturbations and NOE effects indicative of proximity in hydrogen-bonded or stacked complexes, allowing quantification of association constants (K_a) from 10^2 to 10^6 M^{-1} via titration methods.[25] IR spectroscopy reveals frequency shifts in vibrational modes, such as O-H stretches red-shifting by 100-300 cm^{-1} upon hydrogen bond formation, enabling estimation of bond strengths from correlation models.[26] These techniques, often combined with computational validation, distinguish specific interactions in complex mixtures.[27] Despite their versatility, non-covalent interactions face limitations in thermal stability and multi-component competition, constraining applications in dynamic systems. Their weak energies (generally <30 kcal/mol) limit persistence above 100-200°C, leading to dissociation and loss of structure, though cooperativity can raise effective barriers to 20-40 kcal/mol.[20] In multi-component environments, solvent molecules or competing substrates can outcompete target interactions, reducing selectivity and requiring optimized conditions for reliable assembly.[23] These challenges are mitigated through multi-valent designs but remain inherent to the reversible nature of supramolecular bonds.[22]Molecular Recognition and Host-Guest Chemistry

Molecular recognition in supramolecular chemistry refers to the selective binding of a guest molecule by a host molecule through non-covalent interactions, mimicking biological processes such as enzyme-substrate binding. This selectivity arises from the precise complementarity between the host's binding site and the guest's structure, including shape, size, and charge, which minimizes steric repulsion and maximizes favorable interactions. The host typically features a preorganized cavity or pocket designed to accommodate the guest, reducing the energetic cost of reorganization upon complexation.[10] The principle of preorganization, articulated by Donald J. Cram, posits that hosts with binding sites already converged in the correct geometry for guest interaction exhibit higher affinity than those requiring significant structural adjustment, as the latter incurs an unfavorable entropy penalty. For instance, spherands—rigid, bowl-shaped hosts—demonstrate this by forming complexes with alkali metal ions where the host's aromatic units are fixed in position prior to binding. Complementarity ensures that the guest fits snugly, with matching charge distribution enhancing electrostatic attraction and hydrophobic surfaces promoting van der Waals contacts. In host-guest chemistry, the binding equilibrium is quantified by the association constant , where [HG], [H], and [G] are the equilibrium concentrations of the complex, free host, and free guest, respectively; the dissociation constant . Typical values range from to M for strong synthetic hosts, reflecting affinities from moderate to near-irreversible under physiological conditions.[28][10][29] Host-guest complexes often manifest as inclusion complexes, where the guest partially enters a host cavity, or encapsulation complexes, where the guest is fully enclosed, as seen in carcerands that trap guests without escape routes. Binding is influenced by solvation effects, where desolvation of polar groups upon complexation can oppose association unless compensated by host-guest interactions, and by entropy changes, such as the favorable release of ordered solvent molecules from hydrophobic surfaces. Jean-Marie Lehn's cryptate effect describes the enhanced stability of three-dimensional macrobicyclic hosts (cryptands) compared to their open-chain or monocyclic analogs, due to the topological wrapping that provides multiple coordination points and kinetic inertness to dissociation. For example, [2.2.2]-cryptands exhibit values around M for potassium ions in water, far surpassing open-chain analogs of similar donor atom count.[1][30][31] Thermodynamic characterization of these interactions commonly employs isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), which directly measures heat changes during titration to yield , enthalpy , and entropy ; the Gibbs free energy is then calculated as , revealing whether binding is enthalpy- or entropy-driven. In many host-guest systems, negative from direct interactions dominates, while positive from solvent effects contributes favorably, enabling precise evaluation of selectivity and cooperativity.Self-Assembly Processes

Self-assembly in supramolecular chemistry refers to the spontaneous organization of discrete molecular subunits into ordered, structurally complex architectures through non-covalent interactions, driven by the minimization of free energy. This process mimics natural systems, such as protein folding, supramolecular aggregates of proteins like microtubules that enable orderly long-range cooperative effects through hierarchical polymerization of tubulin dimers into protofilaments and tubular structures, or lipid bilayer formation, and enables the construction of functional materials from simple building blocks. Unlike covalent synthesis, self-assembly operates under thermodynamic or kinetic control, allowing for reversible and adaptive structures.[32][33] Key mechanisms of self-assembly include nucleation-growth pathways, where initial small aggregates (nuclei) form stochastically and subsequently grow by incorporating additional monomers, often requiring an energy barrier to overcome supersaturation. Pathway-dependent assembly arises when different sequences of molecular interactions lead to distinct final structures, influenced by concentration, temperature, or solvent conditions. Self-assembly can proceed under equilibrium control, where structures represent the global energy minimum and are reversible, or kinetic control, where metastable states are trapped due to slow interconversion rates, as seen in the rapid formation of non-equilibrium aggregates in out-of-equilibrium systems.[34][35][36] Common types of self-assembled structures include micelles and vesicles formed by amphiphilic molecules, where hydrophobic tails aggregate in aqueous media to shield from water, and helical assemblies arising from chiral building blocks that twist into one-dimensional (1D) fibers. Hierarchical assembly extends this to higher dimensions, progressing from 1D chains or helices to two-dimensional (2D) sheets and three-dimensional (3D) networks, such as layered porphyrin supra-amphiphiles that evolve into tubular or vesicular morphologies. These structures scale molecular recognition events—such as hydrogen bonding or π-π stacking—into multi-component organizations.[37][38][39] The primary driving forces are the minimization of Gibbs free energy (ΔG = ΔH - TΔS), where enthalpic contributions from attractive interactions like van der Waals forces are balanced by entropic gains, particularly in amphiphile aggregation where the release of structured water molecules around hydrophobic groups increases solvent entropy. For instance, in micelle formation, the hydrophobic effect dominates, with critical micelle concentrations typically in the millimolar range for surfactants, leading to spherical aggregates that encapsulate hydrophobic guests.[40][41] Representative examples include synthetic nucleobase analogs that mimic DNA base-pairing through hydrogen bonding to form double-helical nanostructures, achieving fidelity similar to biological duplexes with association constants around 10^6 M^{-1}. Another is metal-ligand coordination polymers, where ditopic ligands bridge metal ions to yield 1D chains or 3D frameworks, such as zinc-terpyridine complexes that self-assemble into linear polymers under mild conditions, demonstrating directional bonding for precise topology control.[42][43][44] Challenges in self-assembly include error correction to favor desired structures over defective ones, often limited by kinetic traps where off-pathway aggregates persist due to high activation energies for rearrangement, as modeled in viral capsid formation where incomplete shells form stable yet non-functional intermediates. Recent advances in the 2020s incorporate data-driven modeling, combining machine learning with molecular dynamics simulations to predict assembly pathways and outcomes, enabling the design of block copolymer micelles with targeted morphologies by training on experimental datasets.[45][46][47][48]Dynamic and Responsive Systems

Dynamic and responsive systems in supramolecular chemistry extend the principles of self-assembly by incorporating reversibility and adaptability, allowing structures to evolve in response to environmental changes rather than remaining static at equilibrium. These systems leverage labile interactions to enable reconfiguration, selection, and feedback mechanisms, mimicking biological processes where adaptability enhances functionality.[49] Dynamic covalent chemistry integrates reversible covalent bonds into supramolecular frameworks, combining the strength of covalent linkages with the adaptability of non-covalent interactions. Seminal work defined this field as chemical reactions conducted reversibly under equilibrium control, enabling error correction and constitutional diversity during assembly.[50] A representative example is imine formation, where aldehydes and amines equilibrate via hydrolysis: This reaction's reversibility under mild conditions facilitates dynamic libraries of structures that can adapt to perturbations.[51] Constitutional dynamic chemistry, pioneered by Jean-Marie Lehn, describes systems where components exchange through reversible bonds, leading to evolving compositions and adaptive behavior. In Lehn's framework, these systems undergo continuous constitutional variation, enabling self-organization by selection and adaptation to external stimuli, as outlined in his 2002 analysis of complex matter formation.[49] Such dynamics allow for the generation of diverse molecular entities from a library of building blocks, with selection driven by thermodynamic or kinetic factors. Non-covalent dynamics further enhance responsiveness through mechanisms like allosteric effects and adaptive binding, where binding at one site modulates interactions at another. Allosteric supramolecular receptors exemplify this, where effector binding induces conformational changes that amplify or inhibit guest recognition, enabling signal transduction and control.[52] Adaptive binding in these systems adjusts affinity in response to environmental cues, promoting efficient molecular recognition without permanent structural alterations. Stimuli-responsive supramolecular systems respond to external triggers such as pH, light, or temperature, triggering disassembly, reconfiguration, or property changes. For instance, pH variations can protonate or deprotonate components, altering hydrogen bonding or electrostatic interactions to control assembly. Temperature shifts influence entropy-driven processes, dissolving aggregates above critical points. Light-responsive examples include azobenzene moieties, which undergo reversible photoisomerization between trans and cis forms upon UV/visible irradiation, modulating host-guest binding or gelation in supramolecular networks.[53] These triggers enable precise temporal and spatial control, with azobenzene-based systems demonstrating rapid switching cycles for applications in smart materials.[54] Recent advances from 2021 to 2025 have focused on adaptive platforms using dynamic bonds for precision medicine, particularly in targeted drug delivery and diagnostics. Supramolecular systems with reversible covalent linkages, such as disulfide or hydrazone bonds, enable stimuli-responsive release of therapeutics in response to tumor microenvironments like elevated glutathione or acidic pH. These platforms integrate dynamic chemistry for on-demand adaptation, improving specificity and reducing off-target effects in cancer theranostics.[55] High-impact contributions include self-assembling nanocarriers that evolve compositions in vivo, enhancing bioavailability and personalized treatment efficacy.[56]Building Blocks

Macrocyclic Compounds

Macrocyclic compounds serve as essential building blocks in supramolecular chemistry, providing rigid, preorganized cavities for guest encapsulation and molecular recognition. These synthetic hosts, typically featuring 10 to 20 atoms in their rings, enable selective binding through non-covalent interactions due to their defined three-dimensional structures.[57] Crown ethers represent one prominent class of macrocyclic compounds, consisting of cyclic polyethers with repeating -CH₂-CH₂-O- units that form a flexible ring capable of coordinating metal cations. First systematically synthesized by Charles J. Pedersen in 1967, these compounds exhibit high selectivity for alkali and alkaline earth metal ions based on cavity size matching the ionic radius of the guest. For instance, 18-crown-6, with six oxygen atoms and a cavity diameter of approximately 2.6–3.2 Å, preferentially binds potassium ions (K⁺, ionic radius 1.33 Å) through multiple ion-dipole interactions.[58][58] The synthesis of crown ethers commonly employs the Williamson ether synthesis, an SN2 reaction involving the cyclization of a diol with a dihalide under high-dilution conditions to favor intramolecular closure over polymerization. Template-directed approaches, using metal ions to preorganize reactants, further enhance yields and selectivity in forming these macrocycles.[59][58] Cyclodextrins, another key type, are toroidal macrocycles composed of 6 to 8 α-1,4-linked D-glucopyranose units, forming a hydrophilic exterior and a hydrophobic interior cavity suitable for encapsulating non-polar guests in aqueous media. The β-cyclodextrin variant, with seven glucose units and a cavity diameter of about 6.0–6.5 Å, is particularly effective for hosting hydrophobic molecules such as dyes or pharmaceuticals, driven by van der Waals forces and hydrophobic effects.[60][60] Calixarenes are basket-shaped macrocycles formed by the cyclic condensation of phenols and formaldehyde, offering a cupped cavity lined with aromatic π-surfaces for guest binding. Synthesized via base-catalyzed reaction of p-tert-butylphenol with formaldehyde, calix[61]arenes possess a smaller cavity (approximately 3.0 Å diameter at the lower rim) ideal for smaller ions or molecules, while larger homologs like calix[62]arenes accommodate bulkier guests up to 11.7 Å.[63][63][64] Cucurbiturils (CB) constitute another important family of macrocycles, featuring a pumpkin-shaped structure composed of n glycoluril units linked by methylene bridges, with two polar carbonyl-fringed portals flanking a hydrophobic cavity. Synthesized through acid-catalyzed condensation of glycoluril and formaldehyde, common variants like CB[65], CB[66], and CB[62] (cavity diameters ~5.5 Å, 7.3 Å, and 8.8 Å, respectively) exhibit exceptionally high binding affinities (up to 10^{15} M^{-1}) for cationic guests in aqueous media, driven by ion-dipole interactions at the portals and hydrophobic encapsulation.[67] Pillararenes, first synthesized in 2008 via acid-catalyzed condensation of 1,4-dimethoxypbenzene, are cylindrical macrocycles composed of repeating 1,4-disubstituted benzene units linked by methylene bridges at para positions, providing a rigid, hydrophobic cavity for guest inclusion via π-π interactions and hydrophobic effects. These planar-symmetric hosts offer tunable cavity sizes (e.g., pillar[68]arene ~4.7 Å diameter) and high symmetry, enabling selective recognition of linear guests like paraquat.[69][70] The binding properties of these macrocycles arise from their cavity dimensions and functional groups, enabling size- and shape-selective recognition; for example, crown ethers show log K association constants up to 6 for K⁺ with 18-crown-6 in methanol, reflecting optimal geometric fit.[58] Functionalized derivatives enhance the versatility of macrocycles by introducing specific binding sites or solubility modifiers, such as appending ammonium groups to calixarenes for improved cation affinity or carboxylic acids to cyclodextrins for pH-responsive encapsulation. These modifications allow tailored host-guest interactions in supramolecular assemblies, often increasing binding constants by 1–2 orders of magnitude compared to parent compounds.[71][71] Despite their advantages, macrocyclic compounds like crown ethers and calixarenes often suffer from limited water solubility due to their hydrophobic frameworks, restricting applications in aqueous environments unless modified with polar substituents. Cyclodextrins, conversely, exhibit moderate aqueous solubility (1.85 g/100 mL at 25 °C for β-cyclodextrin), but synthetic macrocycles generally require solubilizing groups to overcome this limitation.[72][60][73]Synthetic Recognition Motifs

Synthetic recognition motifs encompass a diverse array of non-macrocyclic molecular units engineered to facilitate precise intermolecular interactions through non-covalent forces, enabling the construction of dynamic supramolecular architectures. These motifs are typically open-chain or planar structures designed to exploit hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and metal-ligand coordination for selective recognition and self-assembly. Unlike rigid cyclic hosts, they offer flexibility in integration into larger systems, allowing for tunable binding strengths and responsiveness to external stimuli.[74] Hydrogen bonding motifs based on urea and amide functionalities form robust arrays that promote directional assembly. A seminal example is the ureidopyrimidinone (UPy) unit, which features a self-complementary quadruple hydrogen-bonding pattern in the DADA configuration (donor-acceptor-donor-acceptor), inspired by DNA base pairing. This motif exhibits exceptionally high dimerization constants, on the order of 6 × 10^7 M^{-1} in chloroform for the tautomeric AADD form, enabling the formation of linear supramolecular polymers with mechanical integrity comparable to covalent counterparts. Urea and amide arrays also underpin rosette-like structures, where multiple hydrogen bonds between complementary units create cyclic, hexagonal patterns that stack into columnar organizations, as demonstrated in assemblies of cyanurate and melamine derivatives adapted to synthetic urea scaffolds. These H-bonding motifs are prized for their specificity and reversibility, with association energies typically ranging from 10-30 kcal/mol per array, facilitating adaptive materials.[75] Porphyrin-based motifs leverage π-π stacking interactions between their extended aromatic cores to drive the formation of ordered aggregates. In solution, these motifs self-assemble into slipped-cofacial dimers or J-aggregates, where overlapping π-systems yield cooperative stabilization and characteristic red-shifted absorption spectra, mimicking natural light-harvesting complexes. For instance, zinc porphyrins with peripheral substituents form helical stacks through face-to-face π-interactions, with stacking energies of approximately 4-5 kcal/mol per pair, promoting one-dimensional nanostructures.[76] Bipyridine motifs, conversely, enable metal coordination as recognition elements, chelating transition metals such as Cu(I) or Fe(II) to template the assembly of discrete structures like catenanes and helicates. The bidentate nature of bipyridines provides geometric control, with binding constants often exceeding 10^10 M^{-1} for octahedral complexes, as seen in early templated syntheses that laid the foundation for mechanically interlocked molecules. The synthesis of these motifs emphasizes modular strategies to incorporate recognition elements into functional scaffolds. Click chemistry, particularly the copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), has emerged as a versatile tool for assembling urea, amide, or bipyridine units with high yield (>95%) under mild conditions, allowing precise placement without disrupting non-covalent sites.[77] A key advantage of synthetic recognition motifs lies in their inherent tunability for multi-valent interactions, where multiple motifs on a single scaffold amplify binding affinities via chelate and statistical effects, often increasing association constants by orders of magnitude. This multi-valency enables selective recognition of complex targets, as in bipyridine arrays coordinating multiple metals to form grid-like arrays, or urea motifs clustering for enhanced H-bond cooperativity in adaptive polymers.[77] Such design principles underscore their utility in creating responsive supramolecular systems with precise control over assembly hierarchies.Biomimetic and Biological Units

Biological units play a central role in supramolecular chemistry by providing naturally occurring motifs that drive self-assembly through non-covalent interactions. Peptides, particularly those adopting α-helical conformations, serve as key building blocks due to their ability to form coiled-coil structures via hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding along their helical backbones.[78] These α-helices enable hierarchical self-assembly into nanofibers and higher-order architectures, mimicking protein folding in biological systems.[79] Nucleotides, on the other hand, rely on specific base-pairing interactions—such as Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding between adenine-thymine and guanine-cytosine—to direct precise supramolecular organization in DNA and RNA.[80] This base-pairing not only stabilizes double helices but also facilitates the formation of extended supramolecular networks.[81] Lipids contribute through amphiphilic self-assembly, where hydrophobic tails and hydrophilic heads organize into bilayers that spontaneously form vesicles, encapsulating aqueous contents in a process governed by van der Waals forces and entropy-driven hydrophobic effects.[82] Biomimetic synthesis extends these natural principles by designing synthetic analogs that replicate biological functionality. Artificial nucleobases, engineered to form complementary hydrogen-bonded pairs beyond the canonical set, enable programmable supramolecular assemblies with tunable specificity, such as in metal-mediated base pairing for novel DNA-like structures.[42] Foldamers, which are oligomeric backbones composed of non-natural amino acids or peptoids, mimic protein secondary structures like α-helices and β-sheets, achieving stable conformations through intramolecular hydrogen bonding and steric control.[83] These biomimetic units allow for the creation of robust, sequence-specific scaffolds that emulate the folding and recognition properties of native proteins.[84] Prominent examples illustrate the power of these units in supramolecular design. DNA origami, pioneered by Rothemund in 2006, utilizes a long single-stranded DNA scaffold folded by short staple strands through base-pairing to create arbitrary two-dimensional nanoscale shapes, serving as versatile templates for supramolecular scaffolds.[85] Amyloid fibrils, formed by peptide aggregation into cross-β-sheet structures, represent another exemplar, where β-strands align via hydrogen bonding to yield rigid, hierarchical fibrils that exhibit functional roles in biology beyond pathology.[86] Integration of biological and synthetic components yields hybrid systems with enhanced properties. Peptide-cyclodextrin conjugates combine the recognition capabilities of peptides with the host-guest inclusion properties of cyclodextrins, forming supramolecular complexes that improve solubility, stability, and targeted interactions in aqueous environments.[87] Such hybrids leverage self-assembly to create dynamic assemblies, as observed in biological units. In the 2020s, these biomimetic and biological units have advanced precision medicine, particularly for targeted drug delivery, where peptide-based or nucleotide-driven supramolecular carriers enable site-specific release with minimal off-target effects.[88]Advanced Architectures

Mechanically Interlocked Structures

Mechanically interlocked structures represent a class of supramolecular architectures where molecular components are topologically linked through mechanical bonds rather than covalent connections, enabling unique steric and dynamic behaviors. These structures, pioneered in the late 20th century, include rotaxanes, catenanes, and molecular knots, which mimic macroscopic entanglements at the molecular scale. Rotaxanes consist of a linear "axle" molecule threaded through a macrocyclic "wheel," with bulky stoppers at the axle ends preventing dissociation, as exemplified by early [89]rotaxanes using cyclobis(paraquat-p-phenylene) wheels and dumbbell axles. Catenanes feature two or more interlocked macrocycles, akin to chain links, with the simplest [89]catenane forming a Hopf link topology. Molecular knots, such as the trefoil knot, introduce three-dimensional complexity through overhand knotting of a single molecular strand, first realized in 1989 using a copper(I)-templated double-helix precursor that was cyclized and demetallated.[90] Synthesis of these structures relies on template-directed strategies to achieve high yields by preorganizing components via non-covalent interactions before forming the mechanical bond. A seminal approach for catenanes is the copper(I)-catalyzed clipping method developed by Jean-Pierre Sauvage in 1983, where two phenanthroline ligands coordinate to Cu(I) to form a helical complex, followed by ring closure via Williamson ether synthesis or olefin metathesis, yielding up to 90% for [89]catenanes after demetallation. For rotaxanes, similar Cu(I) templation threads the macrocycle onto a linear precursor, with stoppers added via clipping or azide-alkyne cycloaddition. The slippage method, introduced in 1993 by Fraser Stoddart and coworkers, exploits thermodynamic control: a macrocycle is forced over moderately sized end groups of a dumbbell axle under high temperature or pressure, forming stable [89]rotaxanes in yields of 20-70% without templates, as demonstrated with crown ether wheels and hydroquinone-based axles. Molecular knots like the trefoil are synthesized via Sauvage's double-helix templation, where a linear ligand wraps around two Cu(I) ions before cyclization, producing the knotted topology in low yield (less than 10%), though later optimizations have achieved yields over 80%.[91][92][90][93] The mechanical bond imparts distinctive properties, particularly large-amplitude dynamics that differ from covalently bound systems. In rotaxanes, the interlocked components enable circumrotation (ring rotation around the axle) and translation (ring shuttling along the axle), with energy barriers tunable by non-covalent interactions; for instance, hydrogen-bonded rotaxanes exhibit circumrotation rates accelerated by over six orders of magnitude upon photoisomerization of the axle. Catenanes allow circumrotation and rocking motions between rings, influencing co-conformations and enabling bistable states. In trefoil knots, the topology restricts conformational freedom, leading to compact structures with enhanced rigidity compared to unknotted loops, as seen in lanthanide-templated variants. These dynamics arise from the absence of covalent constraints, allowing energy inputs like pH or light to drive motion, though they are often studied in solution where solvent effects modulate barriers.[94][95][96] Characterization of mechanically interlocked structures employs techniques sensitive to topology and dynamics. X-ray crystallography provides atomic-resolution images of interlocked geometries, confirming ring threading in rotaxanes and link orientations in catenanes, as in the structure of a benzylic amide [89]catenane revealing close π-π stacking contacts. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy distinguishes interlocked states through chemical shift perturbations and variable-temperature studies; for example, 1H NMR of Sauvage's trefoil knot shows symmetry indicative of the chiral topology, while diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) quantifies hydrodynamic volumes larger than non-interlocked analogs. Mass spectrometry, particularly tandem MS, verifies connectivity without fragmentation of mechanical bonds. These methods collectively affirm the persistence of interlockings under standard conditions.[91][90][97] Despite advances, challenges in scalability and purification limit broader applications of mechanically interlocked structures. Template-directed syntheses often require multiple steps and metal removal, yielding complex mixtures that demand chromatography for isolation, with purification yields dropping below 50% for higher-order topologies like Solomon links. Scalability is hindered by low gram-scale outputs in clipping reactions, as seen in early Cu(I) methods producing milligram quantities, and slippage approaches suffer from equilibrium limitations requiring forcing conditions. Ongoing efforts focus on active metal templates and dynamic covalent chemistry to improve efficiency, but economic viability for materials remains elusive.[91][98][99]Supramolecular Polymers

Supramolecular polymers are defined as oligomeric or polymeric arrays of monomeric units that are connected by reversible, highly directional non-covalent interactions, leading to the manifestation of polymer-like properties in both solution and bulk states.[75] This concept, formalized by Meijer and colleagues, requires association constants typically exceeding to M to achieve sufficient chain lengths and mechanical integrity comparable to traditional covalent polymers. Unlike conventional polymers linked by strong covalent bonds, these structures rely on interactions such as hydrogen bonding, - stacking, or metal-ligand coordination, enabling dynamic behavior at the molecular level.[75] Various types of supramolecular polymers exist, distinguished by the placement and role of non-covalent bonds. Main-chain supramolecular polymers feature directional interactions along the primary backbone, exemplified by telechelic oligomers with ureidopyrimidinone (UPy) end groups that form linear chains through quadruple hydrogen bonding. Side-chain variants incorporate non-covalent motifs as pendant groups on a covalent polymer scaffold, allowing modular functionalization and responsiveness.[100] Supramolecular gels, a cross-linked subtype, arise from multifunctional monomers creating networked assemblies via multiple interactions, resulting in soft, viscoelastic materials suitable for dynamic applications.[101] The properties of supramolecular polymers stem directly from their non-covalent connectivity, offering advantages over covalent analogs. Reversibility allows for stimuli-induced disassembly and reformation, with bond energies ranging from 1 to 120 kJ/mol compared to 150–1000 kJ/mol for covalent bonds.[101] This dynamic nature facilitates self-healing, where structural defects mend autonomously through rebinding of motifs, as demonstrated in UPy-based systems that recover mechanical strength post-damage.[102] Viscosity and rheological behavior are tunable via the strength of association constants (), where higher values promote longer chains and higher viscosities, enabling control over flow properties in solution.[75] Synthesis of supramolecular polymers predominantly employs step-growth approaches, where bifunctional or multifunctional monomers bearing complementary recognition motifs spontaneously assemble under equilibrium conditions.[75] Early seminal contributions from Meijer's group in the 1990s utilized hydrogen-bonding arrays, such as the self-complementary UPy dimer (with M in apolar solvents), to form high-molecular-weight main-chain polymers via simple mixing of telechelic precursors. These methods have evolved to include host-guest inclusions and metal coordination, allowing precise control over chain length and topology through monomer design.[75] Self-assembly processes underpin this polymerization, directing monomers into ordered chains through thermodynamic favorability of the interactions.[75] Recent advances from 2020 to 2025 have emphasized responsive supramolecular polymers capable of adapting to external stimuli, paving the way for sustainable and multifunctional materials. Innovations include pH-responsive hybrids integrating UPy motifs with -sheet peptides, which exhibit morphological switches between fibrillar and globular states in response to pH changes, enhancing adaptability.[103] Stimuli-responsive designs, such as those undergoing monomer exchange in UPy networks, have enabled dynamic reconfiguration for recyclable systems, reducing material waste.[104] Toward sustainability, efforts have focused on bio-based and recyclable architectures, like supramolecular modifications of high-molar-mass biopolymers, balancing toughness with degradability to minimize environmental impact.[105] Emerging developments as of 2025 include data-driven strategies for characterizing solution-phase assemblies using advanced spectroscopy and computation, as well as supramolecular systems for precision medicine enabling targeted drug delivery and adaptive therapeutics through non-covalent dynamics.[106][55] These developments highlight the potential for supramolecular polymers in creating circular material economies.Molecular Devices and Machinery