Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

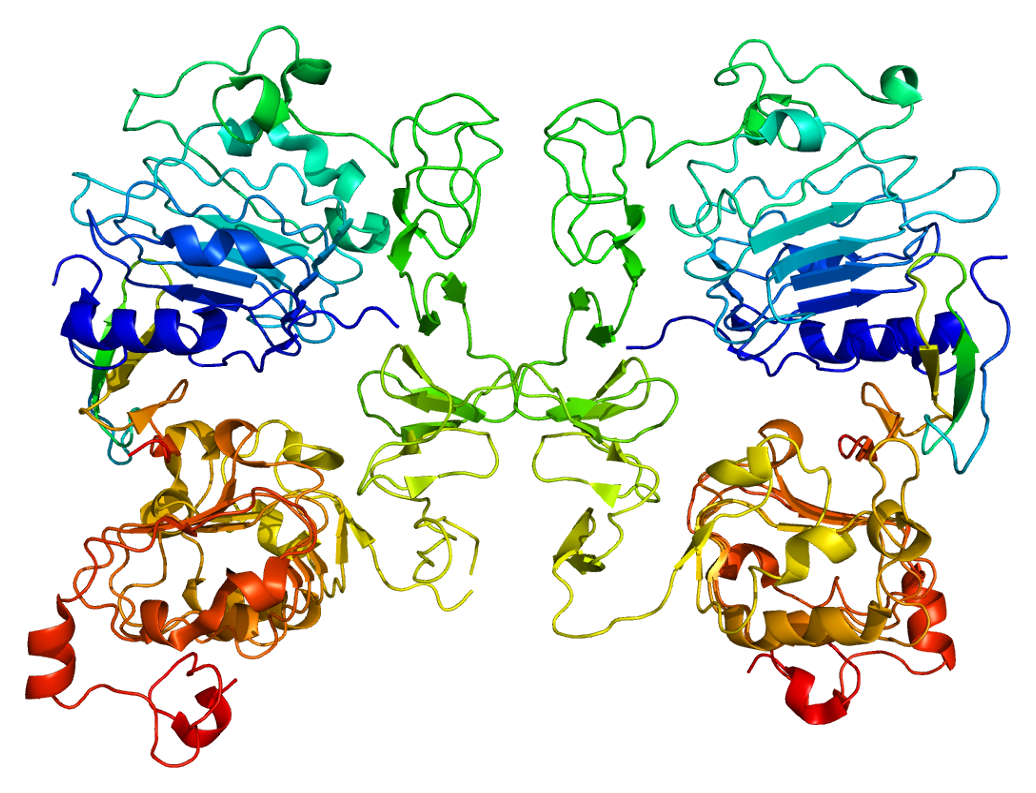

TGF alpha

View on Wikipedia

Transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-α) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TGFA gene.[5] As a member of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) family, TGF-α is a mitogenic polypeptide.[6] The protein becomes activated when binding to receptors capable of protein kinase activity for cellular signaling.

TGF-α is a transforming growth factor that is a ligand for the epidermal growth factor receptor, which activates a signaling pathway for cell proliferation, differentiation and development. This protein may act as either a transmembrane-bound ligand or a soluble ligand. This gene has been associated with many types of cancers, and it may also be involved in some cases of cleft lip/palate.[5]

Synthesis

[edit]TGF-α is synthesized internally as part of a 160 (human) or 159 (rat) amino acid transmembrane precursor.[7] The precursor is composed of an extracellular domain containing a hydrophobic transmembrane domain, 50 amino acids of TGF-α, and a 35-residue-long cytoplasmic domain.[7] In its smallest form, TGF-α has six cysteines linked together via three disulfide bridges. Collectively, all members of the EGF/TGF-α family share this structure. The protein, however, is not directly related to TGF-β.

Limited success has resulted from attempts to synthesize of a reductant molecule to TGF-α that displays a similar biological profile.[8]

Synthesis in the stomach

[edit]In the stomach, TGF-α is manufactured within the normal gastric mucosa.[9] TGF-α has been shown to inhibit gastric acid secretion.

Function

[edit]TGF-α can be produced in macrophages, brain cells, and keratinocytes. TGF-α induces epithelial development. Considering that TGF-α is a member of the EGF family, the biological actions of TGF-α and EGF are similar. For instance, TGF-α and EGF bind to the same receptor. When TGF-α binds to EGFR it can initiate multiple cell proliferation events.[8] Cell proliferation events that involve TGF-α bound to EGFR include wound healing and embryogenesis. TGF-α is also involved in tumerogenesis and believed to promote angiogenesis.[7]

TGF-α has also been shown to stimulate neural cell proliferation in the adult injured brain.[10]

Receptor

[edit]A 170-kDa glycosylated protein known as the EGF receptor binds to TGF-α allowing the polypeptide to function in various signaling pathways.[6] The EGF receptor is characterized by having an extracellular domain that has numerous amino acid motifs. EGFR is essential for a single transmembrane domain, an intracellular domain (containing tyrosine kinase activity), and ligand recognition.[6] As a membrane anchored-growth factor, TGF-α can be cleaved from an integral membrane glycoprotein via a protease.[7] Soluble forms of TGF-α resulting from the cleavage have the capacity to activate EGFR. EGFR can be activated from a membrane-anchored growth factor as well.

When TGF-α binds to EGFR it dimerizes triggering phosphorylation of a protein-tyrosine kinase. The activity of protein-tyrosine kinase causes an autophosphorylation to occur among several tyrosine residues within EGFR, influencing activation and signaling of other proteins that interact in many signal transduction pathways.

Animal studies

[edit]In an animal model of Parkinson's disease where dopaminergic neurons have been damaged by 6-hydroxydopamine, infusion of TGF-α into the brain caused an increase in the number of neuronal precursor cells.[10] However TGF-α treatment did not result in neurogenesis of dopaminergic neurons.[11]

Human studies

[edit]Neuroendocrine system

[edit]The EGF/TGF-α family has been shown to regulate luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) through a glial-neuronal interactive process.[6] Produced in hypothalamic astrocytes, TGF-α indirectly stimulates LHRH release through various intermediates. As a result, TGF-α is a physiological component essential to the initiation process of female puberty.[6]

Suprachiasmatic nucleus

[edit]TGF-α has also been observed to be highly expressed in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) (5). This finding suggests a role for EGFR signaling in the regulation of CLOCK and circadian rhythms within the SCN.[12] Similar studies have shown that when injected into the third ventricle TGF-α can suppress circadian locomotor behavior along with drinking or eating activities.[12]

Tumors

[edit]This protein shows potential use as a prognostic biomarker in various tumors, like gastric carcinoma.[13] or melanoma has been suggested.[14] Elevated TGF-α is associated with Menetrier's disease, a precancerous condition of the stomach.[15]

Interactions

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000163235 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000029999 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: TGFA transforming growth factor alpha".

- ^ a b c d e Ojeda SR, Ma YJ, Rage F (September 1997). "The transforming growth factor alpha gene family is involved in the neuroendocrine control of mammalian puberty". Molecular Psychiatry. 2 (5): 355–358. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000307. PMID 9322223. S2CID 20268790.

- ^ a b c d Ferrer I, Alcántara S, Ballabriga J, Olivé M, Blanco R, Rivera R, et al. (June 1996). "Transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF-alpha) and epidermal growth factor-receptor (EGF-R) immunoreactivity in normal and pathologic brain". Progress in Neurobiology. 49 (2): 99–123. doi:10.1016/0301-0082(96)00009-3. PMID 8844822.

- ^ a b McInnes C, Wang J, Al Moustafa AE, Yansouni C, O'Connor-McCourt M, Sykes BD (October 1998). "Structure-based minimization of transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF-alpha) through NMR analysis of the receptor-bound ligand. Design, solution structure, and activity of TGF-alpha 8-50". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (42): 27357–27363. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.42.27357. PMID 9765263.

- ^ Coffey RJ, Gangarosa LM, Damstrup L, Dempsey PJ (October 1995). "Basic actions of transforming growth factor-alpha and related peptides". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 7 (10): 923–7. doi:10.1097/00042737-199510000-00003. PMID 8590135.

- ^ a b Fallon J, Reid S, Kinyamu R, Opole I, Opole R, Baratta J, et al. (December 2000). "In vivo induction of massive proliferation, directed migration, and differentiation of neural cells in the adult mammalian brain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (26): 14686–14691. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9714686F. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.26.14686. PMC 18979. PMID 11121069.

- ^ Cooper O, Isacson O (October 2004). "Intrastriatal transforming growth factor alpha delivery to a model of Parkinson's disease induces proliferation and migration of endogenous adult neural progenitor cells without differentiation into dopaminergic neurons". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (41): 8924–8931. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2344-04.2004. PMC 2613225. PMID 15483111.

- ^ a b Hao H, Schwaber J (May 2006). "Epidermal growth factor receptor induced Erk phosphorylation in the suprachiasmatic nucleus". Brain Research. 1088 (1): 45–8. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.100. PMID 16630586.

- ^ Fanelli MF, Chinen LT, Begnami MD, Costa WL, Fregnami JH, Soares FA, et al. (August 2012). "The influence of transforming growth factor-α, cyclooxygenase-2, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-7, MMP-9 and CXCR4 proteins involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition on overall survival of patients with gastric cancer". Histopathology. 61 (2): 153–161. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04139.x. PMID 22582975. S2CID 6566296.

- ^ Tarhini AA, Lin Y, Yeku O, LaFramboise WA, Ashraf M, Sander C, et al. (January 2014). "A four-marker signature of TNF-RII, TGF-α, TIMP-1 and CRP is prognostic of worse survival in high-risk surgically resected melanoma". Journal of Translational Medicine. 12: 19. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-12-19. PMC 3909384. PMID 24457057.

- ^ Coffey RJ, Washington MK, Corless CL, Heinrich MC (January 2007). "Ménétrier disease and gastrointestinal stromal tumors: hyperproliferative disorders of the stomach". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (1): 70–80. doi:10.1172/JCI30491. PMC 1716220. PMID 17200708.

- ^ a b Barr FA, Preisinger C, Kopajtich R, Körner R (December 2001). "Golgi matrix proteins interact with p24 cargo receptors and aid their efficient retention in the Golgi apparatus". The Journal of Cell Biology. 155 (6): 885–891. doi:10.1083/jcb.200108102. PMC 2150891. PMID 11739402.

Further reading

[edit]- Luetteke NC, Lee DC (August 1990). "Transforming growth factor alpha: expression, regulation and biological action of its integral membrane precursor". Seminars in Cancer Biology. 1 (4): 265–275. PMID 2103501.

- Greten FR, Wagner M, Weber CK, Zechner U, Adler G, Schmid RM (2002). "TGF alpha transgenic mice. A model of pancreatic cancer development". Pancreatology. 1 (4): 363–368. doi:10.1159/000055835. PMID 12120215. S2CID 84256727.

- Vieira AR (May 2006). "Association between the transforming growth factor alpha gene and nonsyndromic oral clefts: a HuGE review". American Journal of Epidemiology. 163 (9): 790–810. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj103. PMID 16495466.

- Nasim MM, Thomas DM, Alison MR, Filipe MI (April 1992). "Transforming growth factor alpha expression in normal gastric mucosa, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and gastric carcinoma--an immunohistochemical study". Histopathology. 20 (4): 339–343. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1992.tb00991.x. PMID 1577411. S2CID 73067240.

- Thomas DM, Nasim MM, Gullick WJ, Alison MR (May 1992). "Immunoreactivity of transforming growth factor alpha in the normal adult gastrointestinal tract". Gut. 33 (5): 628–631. doi:10.1136/gut.33.5.628. PMC 1379291. PMID 1612477.

- Bean MF, Carr SA (March 1992). "Characterization of disulfide bond position in proteins and sequence analysis of cystine-bridged peptides by tandem mass spectrometry". Analytical Biochemistry. 201 (2): 216–226. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(92)90331-Z. PMID 1632509.

- Lei ZM, Rao CV (August 1992). "Expression of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor and its ligands, EGF and transforming growth factor-alpha, in human fallopian tubes". Endocrinology. 131 (2): 947–957. doi:10.1210/endo.131.2.1639032. PMID 1639032.

- Werner S, Roth WK, Bates B, Goldfarb M, Hofschneider PH (November 1991). "Fibroblast growth factor 5 proto-oncogene is expressed in normal human fibroblasts and induced by serum growth factors". Oncogene. 6 (11): 2137–2144. PMID 1658709.

- Saeki T, Cristiano A, Lynch MJ, Brattain M, Kim N, Normanno N, et al. (December 1991). "Regulation by estrogen through the 5'-flanking region of the transforming growth factor alpha gene". Molecular Endocrinology. 5 (12): 1955–1963. doi:10.1210/mend-5-12-1955. PMID 1791840.

- Harvey TS, Wilkinson AJ, Tappin MJ, Cooke RM, Campbell ID (June 1991). "The solution structure of human transforming growth factor alpha". European Journal of Biochemistry. 198 (3): 555–562. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16050.x. PMID 2050136.

- Kline TP, Brown FK, Brown SC, Jeffs PW, Kopple KD, Mueller L (August 1990). "Solution structures of human transforming growth factor alpha derived from 1H NMR data". Biochemistry. 29 (34): 7805–7813. doi:10.1021/bi00486a005. PMID 2261437.

- Jakowlew SB, Kondaiah P, Dillard PJ, Sporn MB, Roberts AB (November 1988). "A novel low molecular weight ribonucleic acid (RNA) related to transforming growth factor alpha messenger RNA". Molecular Endocrinology. 2 (11): 1056–1063. doi:10.1210/mend-2-11-1056. PMID 2464748.

- Jakobovits EB, Schlokat U, Vannice JL, Derynck R, Levinson AD (December 1988). "The human transforming growth factor alpha promoter directs transcription initiation from a single site in the absence of a TATA sequence". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 8 (12): 5549–5554. doi:10.1128/mcb.8.12.5549. PMC 365660. PMID 2907605.

- Tricoli JV, Nakai H, Byers MG, Rall LB, Bell GI, Shows TB (1986). "The gene for human transforming growth factor alpha is on the short arm of chromosome 2". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 42 (1–2): 94–98. doi:10.1159/000132258. PMID 3459638.

- Lee DC, Rose TM, Webb NR, Todaro GJ (1985). "Cloning and sequence analysis of a cDNA for rat transforming growth factor-alpha". Nature. 313 (6002): 489–491. Bibcode:1985Natur.313..489L. doi:10.1038/313489a0. PMID 3855503. S2CID 4358296.

- Derynck R, Roberts AB, Winkler ME, Chen EY, Goeddel DV (August 1984). "Human transforming growth factor-alpha: precursor structure and expression in E. coli". Cell. 38 (1): 287–297. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90550-6. PMID 6088071. S2CID 53275849.

- Ogbureke KU, MacDaniel RK, Jacob RS, Durban EM (July 1995). "Distribution of immunoreactive transforming growth factor-alpha in non-neoplastic human salivary glands". Histology and Histopathology. 10 (3): 691–696. PMID 7579819.

- Walz TM, Malm C, Nishikawa BK, Wasteson A (May 1995). "Transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF-alpha) in human bone marrow: demonstration of TGF-alpha in erythroblasts and eosinophilic precursor cells and of epidermal growth factor receptors in blastlike cells of myelomonocytic origin". Blood. 85 (9): 2385–2392. doi:10.1182/blood.V85.9.2385.bloodjournal8592385. PMID 7727772.

- Patel B, Hiscott P, Charteris D, Mather J, McLeod D, Boulton M (September 1994). "Retinal and preretinal localisation of epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha, and their receptor in proliferative diabetic retinopathy". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 78 (9): 714–718. doi:10.1136/bjo.78.9.714. PMC 504912. PMID 7947554.

External links

[edit]- Transforming+Growth+Factor+alpha at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.