Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

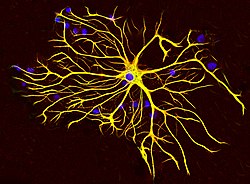

Astrocyte

View on Wikipedia| Astrocyte | |

|---|---|

An astrocyte from a rat brain grown in tissue culture and stained with antibodies to GFAP (red) and vimentin (green). Both proteins are present in large amounts in the intermediate filaments of this cell, so the cell appears yellow. The blue material shows DNA visualized with DAPI stain, and reveals the nucleus of the astrocyte and of other cells. Image courtesy of EnCor Biotechnology Inc. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Glioblast |

| Location | Brain and spinal cord |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | astrocytus |

| MeSH | D001253 |

| NeuroLex ID | sao1394521419 |

| TH | H2.00.06.2.00002, H2.00.06.2.01008 |

| FMA | 54537 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Astrocytes (from Ancient Greek ἄστρον, ástron, "star" and κύτος, kútos, "cavity", "cell"), also known collectively as astroglia, are characteristic star-shaped glial cells in the brain and spinal cord. They perform many functions, including biochemical control of endothelial cells that form the blood–brain barrier,[1] provision of nutrients to the nervous tissue, maintenance of extracellular ion balance, regulation of cerebral blood flow, and a role in the repair and scarring process of the brain and spinal cord following infection and traumatic injuries.[2] The proportion of astrocytes in the brain is not well defined; depending on the counting technique used, studies have found that the astrocyte proportion varies by region and ranges from 20% to around 40% of all glia.[3] Another study reports that astrocytes are the most numerous cell type in the brain.[2] Astrocytes are the major source of cholesterol in the central nervous system.[4] Apolipoprotein E transports cholesterol from astrocytes to neurons and other glial cells, regulating cell signaling in the brain.[4] Astrocytes in humans are more than twenty times larger than in rodent brains, and make contact with more than ten times the number of synapses.[5]

Research since the mid-1990s has shown that astrocytes propagate intercellular Ca2+ waves over long distances in response to stimulation, and, similar to neurons, release transmitters (called gliotransmitters) in a Ca2+-dependent manner.[6] Data suggest that astrocytes also signal to neurons through Ca2+-dependent release of glutamate.[7] Such discoveries have made astrocytes an important area of research within the field of neuroscience.

Structure

[edit]

Astrocytes are a sub-type of glial cells in the central nervous system. They are also known as astrocytic glial cells. Star-shaped, their many processes envelop synapses made by neurons. In humans, a single astrocyte cell can interact with up to 2 million synapses at a time.[8] Astrocytes are classically identified using histological analysis; many of these cells express the intermediate filament glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).[9]

Types

[edit]Several forms of astrocytes exist in the central nervous system: including fibrous (in white matter), protoplasmic (in grey matter), and radial.

Fibrous glia

[edit]The fibrous glia are usually located within white matter, have relatively few organelles, and exhibit long unbranched cellular processes. This type often has astrocytic endfeet processes that physically connect the cells to the outside of capillary walls when they are in proximity to them.[10]

Protoplasmic glia

[edit]The protoplasmic glia are the most prevalent and are found in grey matter tissue, possess a larger quantity of organelles, and exhibit short and highly branched tertiary processes.[citation needed]

Radial glia

[edit]The radial glial cells are disposed in planes perpendicular to the axes of ventricles. One of their processes abuts the pia mater, while the other is deeply buried in gray matter. Radial glia are mostly present during development, playing a role in neuron migration. Müller cells of the retina and Bergmann glia cells of the cerebellar cortex represent an exception, being present still during adulthood. When in proximity to the pia mater, all three forms of astrocytes send out processes to form the pia-glial membrane.

Energy use

[edit]Early assessments of energy use in gray matter signaling suggested that 95% was attributed to neurons and 5% to astrocytes.[11] However, after discovering that action potentials were more efficient than initially believed, the energy budget was adjusted: 70% for dendrites, 15% for axons, and 7% for astrocytes.[12] Previous accounts assumed that astrocytes captured synaptic K⁺ solely via Kir4.1 channels. However, it's now understood they also utilize Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase. Factoring in this active buffering, astrocytic energy demand increases by >200%. This is supported by 3D neuropil reconstructions indicating similar mitochondrial densities in both cell types, as well as cell-specific transcriptomic and proteomic data, and tricarboxylic acid cycle rates.[13] Therefore "Gram-per-gram, astrocytes turn out to be as expensive as neurons".[13]

Development

[edit]

Astrocytes are macroglial cells in the central nervous system. Astrocytes are derived from heterogeneous populations of progenitor cells in the neuroepithelium of the developing central nervous system. There is remarkable similarity between the well known genetic mechanisms that specify the lineage of diverse neuron subtypes and that of macroglial cells.[14] Just as with neuronal cell specification, canonical signaling factors like sonic hedgehog (SHH), fibroblast growth factor (FGFs), WNTs and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), provide positional information to developing macroglial cells through morphogen gradients along the dorsal–ventral, anterior–posterior and medial–lateral axes. The resultant patterning along the neuraxis leads to segmentation of the neuroepithelium into progenitor domains (p0, p1 p2, p3 and pMN) for distinct neuron types in the developing spinal cord. On the basis of several studies it is now believed that this model also applies to macroglial cell specification. Studies carried out by Hochstim and colleagues have demonstrated that three distinct populations of astrocytes arise from the p1, p2 and p3 domains.[15] These subtypes of astrocytes can be identified on the basis of their expression of different transcription factors (PAX6, NKX6.1) and cell surface markers (reelin and SLIT1). The three populations of astrocyte subtypes which have been identified are: 1) dorsally located VA1 astrocytes, derived from p1 domain, express PAX6 and reelin; 2) ventrally located VA3 astrocytes, derived from p3, express NKX6.1 and SLIT1; and 3) intermediate white-matter located VA2 astrocyte, derived from the p2 domain, which express PAX6, NKX6.1, reelin and SLIT1.[16] After astrocyte specification has occurred in the developing CNS, it is believed that astrocyte precursors migrate to their final positions within the nervous system before the process of terminal differentiation occurs.

Function

[edit]

Astrocytes help form the physical structure of the brain, and are thought to play a number of active roles, including the secretion or absorption of neural transmitters and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier.[18] The concept of a tripartite synapse has been proposed, referring to the tight relationship occurring at synapses among a presynaptic element, a postsynaptic element, and a glial element.[19]

- Structural: They are involved in the physical structuring of the brain. Astrocytes get their name because they are star-shaped. They are the most abundant glial cells in the brain that are closely associated with neuronal synapses. They regulate the transmission of electrical impulses within the brain.

- Glycogen fuel reserve buffer: Astrocytes contain glycogen and are capable of gluconeogenesis. The astrocytes next to neurons in the frontal cortex and hippocampus store and release glucose. Thus, astrocytes can fuel neurons with glucose during periods of high rate of glucose consumption and glucose shortage. A recent research on rats suggests there may be a connection between this activity and physical exercise.[20]

- Metabolic support: They provide neurons with nutrients such as lactate.

- Glucose sensing: normally associated with neurons, the detection of interstitial glucose levels within the brain is also controlled by astrocytes. Astrocytes in vitro become activated by low glucose and are in vivo this activation increases gastric emptying to increase digestion.[21]

- Blood–brain barrier: The astrocyte endfeet processes encircling endothelial cells were thought to aid in the maintenance of the blood–brain barrier, and recent research indicates that they do play a substantial role, along with the tight junctions and basal lamina.[citation needed] However, it has recently been shown that astrocyte activity is linked to blood flow in the brain, and that this is what is actually being measured in fMRI.[22][23]

- Transmitter uptake and release: Astrocytes express plasma membrane transporters for several neurotransmitters, including glutamate, ATP, and GABA. More recently, astrocytes were shown to release glutamate or ATP in a vesicular, Ca2+-dependent manner.[24] (This has been disputed for hippocampal astrocytes.)[25]

- Regulation of ion concentration in the extracellular space: Astrocytes express potassium channels at a high density. When neurons are active, they release potassium, increasing the local extracellular concentration. Because astrocytes are highly permeable to potassium, they rapidly clear the excess accumulation in the extracellular space.[26] If this function is interfered with, the extracellular concentration of potassium will rise, leading to neuronal depolarization by the Goldman equation. Abnormal accumulation of extracellular potassium is well known to result in epileptic neuronal activity.[27]

- Modulation of synaptic transmission: In the supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus, rapid changes in astrocyte morphology have been shown to affect heterosynaptic transmission between neurons.[28] In the hippocampus, astrocytes suppress synaptic transmission by releasing ATP, which is hydrolyzed by ectonucleotidases to yield adenosine. Adenosine acts on neuronal adenosine receptors to inhibit synaptic transmission, thereby increasing the dynamic range available for LTP.[29]

- Vasomodulation: Astrocytes may serve as intermediaries in neuronal regulation of blood flow.[30]

- Promotion of the myelinating activity of oligodendrocytes: Electrical activity in neurons causes them to release ATP, which serves as an important stimulus for myelin to form. However, the ATP does not act directly on oligodendrocytes. Instead, it causes astrocytes to secrete cytokine leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), a regulatory protein that promotes the myelinating activity of oligodendrocytes. This suggests that astrocytes have an executive-coordinating role in the brain.[31]

- Nervous system repair: Upon injury to nerve cells within the central nervous system, astrocytes fill up the space to form a glial scar, and may contribute to neural repair. The role of astrocytes in CNS regeneration following injury is not well understood though. The glial scar has traditionally been described as an impermeable barrier to regeneration, thus implicating a negative role in axon regeneration. However, recently, it was found through genetic ablation studies that astrocytes are actually required for regeneration to occur.[32] More importantly, the authors found that the astrocyte scar is actually essential for stimulated axons (that axons that have been coaxed to grow via neurotrophic supplementation) to extend through the injured spinal cord.[32] Astrocytes that have been pushed into a reactive phenotype (termed astrogliosis, defined by the upregulation of among others, GFAP and vimentin[33] expression, a definition still under debate) may actually be toxic to neurons, releasing signals that can kill neurons.[34] Much work, however, remains to elucidate their role in nervous system injury.

- Long-term potentiation: There is debate among scientists as to whether astrocytes integrate learning and memory in the hippocampus. Recently, it has been shown that engrafting human glial progenitor cell in nascent mice brains causes the cells to differentiate into astrocytes. After differentiation, these cells increase LTP and improve memory performance in the mice.[35]

- Circadian clock: Astrocytes alone are sufficient to drive the molecular oscillations in the SCN and circadian behavior in mice, and thus can autonomously initiate and sustain complex mammalian behavior.[36]

- The switch of the nervous system: Based on the evidence listed below, it has been recently conjectured in,[37] that macro glia (and astrocytes in particular) act both as a lossy neurotransmitter capacitor and as the logical switch of the nervous system. I.e., macroglia either block or enable the propagation of the stimulus along the nervous system, depending on their membrane state and the level of the stimulus.

| Evidence type | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium evidence | Calcium waves appear only if a certain concentration of neurotransmitter is exceeded | [39][40][41] |

| Electrophysiological evidence | A negative wave appears when the stimulus level crosses a certain threshold. The shape of the electrophysiological response is different and has the opposite polarity compared to the characteristic neural response, suggesting that cells other than neurons might be involved. | [42][43] |

| Psychophysical evidence | The negative electrophysiological response is accompanied with all-or-none actions. A moderate negative electrophysiological response appears in conscious logical decisions such as perception tasks. An intense sharp negative wave appear in epileptic seizures and during reflexes. | [42][45][43][44] |

| Radioactivity based glutamate uptake tests | Glutamate uptake tests indicate that astrocyte process glutamate in a rate which is initially proportional to glutamate concentration. This supports the leaky capacitor model, where the 'leak' is glutamate processing by glia's glutamine synthetase. Furthermore, the same tests indicate on a saturation level after which neurotransmitter uptake level stops rising proportionally to neurotransmitter concentration. The latter supports the existence of a threshold. The graphs which show these characteristics are referred to as Michaelis-Menten graphs | [46] |

Astrocytes are linked by gap junctions, creating an electrically coupled (functional) syncytium.[47] Because of this ability of astrocytes to communicate with their neighbors, changes in the activity of one astrocyte can have repercussions on the activities of others that are quite distant from the original astrocyte.

An influx of Ca2+ ions into astrocytes is the essential change that ultimately generates calcium waves. Because this influx is directly caused by an increase in blood flow to the brain, calcium waves are said to be a kind of hemodynamic response function. An increase in intracellular calcium concentration can propagate outwards through this functional syncytium. Mechanisms of calcium wave propagation include diffusion of calcium ions and IP3 through gap junctions and extracellular ATP signalling.[48] Calcium elevations are the primary known axis of activation in astrocytes, and are necessary and sufficient for some types of astrocytic glutamate release.[49] Given the importance of calcium signaling in astrocytes, tight regulatory mechanisms for the progression of the spatio-temporal calcium signaling have been developed. Via mathematical analysis it has been shown that localized inflow of Ca2+ ions yields a localized raise in the cytosolic concentration of Ca2+ ions.[50] Moreover, cytosolic Ca2+ accumulation is independent of every intracellular calcium flux and depends on the Ca2+ exchange across the membrane, cytosolic calcium diffusion, geometry of the cell, extracellular calcium perturbation, and initial concentrations.[50]

Tripartite synapse

[edit]Within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, activated astrocytes have the ability to respond to almost all neurotransmitters[51] and, upon activation, release a multitude of neuroactive molecules such as glutamate, ATP, nitric oxide (NO), and prostaglandins (PG), which in turn influences neuronal excitability. The close association between astrocytes and presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals as well as their ability to integrate synaptic activity and release neuromodulators has been termed the tripartite synapse.[19] Synaptic modulation by astrocytes takes place because of this three-part association.

A 2023 study suggested astrocytes, previously underexplored brain cells, could be key to extending wakefulness without negative effects on cognition and health.[52]

Glutamatergic gliotransmission

[edit]Some specialized astrocytes mediate glutamatergic gliotransmission in the central nervous system.[53] Such cells have been called hybrid brain cells because they exhibit both neuron-like and glial-like properties. Unlike traditional neurons, these cells not only transmit electrical signals but also provide supportive roles typically associated with glial cells, such as regulating the brain's extracellular environment and maintaining overall homeostasis.[54][55][56]

Clinical significance

[edit]Astrocytomas

[edit]Astrocytomas are primary tumors in the CNS that develop from astrocytes. It is also possible that glial progenitors or neural stem cells can give rise to astrocytomas. These tumors may occur in many parts of the brain or spinal cord. Astrocytomas are divided into two categories: low grade (I and II) and high grade (III and IV). Low grade tumors are more common in children, and high grade tumors are more common in adults. Malignant astrocytomas are more prevalent among men, contributing to worse survival.[57]

Pilocytic astrocytomas are grade I tumors. They are considered benign and slow growing tumors. Pilocytic astrocytomas frequently have cystic portions filled with fluid and a nodule, which is the solid portion. Most are located in the cerebellum. Therefore, most symptoms are related to balance or coordination difficulties.[57] They also occur more frequently in children and teens.[58]

Fibrillary astrocytomas are grade II tumors. They grow relatively slowly so are usually considered benign, but they infiltrate the surrounding healthy tissue and can become malignant. Fibrillary astrocytomas commonly occur in younger people, who often present with seizures.[58]

Anaplastic astrocytomas are grade III malignant tumors. They grow more rapidly than lower grade tumors. Anaplastic astrocytomas recur more frequently than lower grade tumors because their tendency to spread into surrounding tissue makes them difficult to completely remove surgically.[57]

Glioblastoma is a grade IV cancer that may originate from astrocytes or an existing astrocytoma. Approximately 50% of all brain tumors are glioblastomas. Glioblastomas can contain multiple glial cell types, including astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Glioblastomas are generally considered to be the most invasive type of glial tumor, as they grow rapidly and spread to nearby tissue. Treatment may be complicated, because one tumor cell type may die off in response to a particular treatment while the other cell types may continue to multiply.[57]

Neurodevelopmental disorders

[edit]Astrocytes have emerged as important participants in various neurodevelopmental disorders. This view states that astrocyte dysfunction may result in improper neural circuitry, which underlies certain psychiatric disorders such as autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia.[59][5]

Chronic pain

[edit]Under normal conditions, pain conduction begins with some noxious signal followed by an action potential carried by nociceptive (pain sensing) afferent neurons, which elicit excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSP) in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. That message is then relayed to the cerebral cortex, where we translate those EPSPs into "pain". Since the discovery of astrocyte-neuron signaling, our understanding of the conduction of pain has been dramatically complicated. Pain processing is no longer seen as a repetitive relay of signals from body to brain, but as a complex system that can be up- and down-regulated by a number of different factors. One factor at the forefront of recent research is in the pain-potentiating synapse located in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and the role of astrocytes in encapsulating these synapses. Garrison and co-workers[60] were the first to suggest association when they found a correlation between astrocyte hypertrophy in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and hypersensitivity to pain after peripheral nerve injury, typically considered an indicator of glial activation after injury. Astrocytes detect neuronal activity and can release chemical transmitters, which in turn control synaptic activity.[51][61][62] In the past, hyperalgesia was thought to be modulated by the release of substance P and excitatory amino acids (EAA), such as glutamate, from the presynaptic afferent nerve terminals in the spinal cord dorsal horn. Subsequent activation of AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid), NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) and kainate subtypes of ionotropic glutamate receptors follows. It is the activation of these receptors that potentiates the pain signal up the spinal cord. This idea, although true, is an oversimplification of pain transduction. A litany of other neurotransmitter and neuromodulators, such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), somatostatin, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), galanin, and vasopressin are all synthesized and released in response to noxious stimuli. In addition to each of these regulatory factors, several other interactions between pain-transmitting neurons and other neurons in the dorsal horn have added impact on pain pathways.

Two states of persistent pain

[edit]After persistent peripheral tissue damage there is a release of several factors from the injured tissue as well as in the spinal dorsal horn. These factors increase the responsiveness of the dorsal horn pain-projection neurons to ensuing stimuli, termed "spinal sensitization", thus amplifying the pain impulse to the brain. Release of glutamate, substance P, and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) mediates NMDAR activation (originally silent because it is plugged by Mg2+), thus aiding in depolarization of the postsynaptic pain-transmitting neurons (PTN). In addition, activation of IP3 signaling and MAPKs (mitogen-activated protein kinases) such as ERK and JNK, bring about an increase in the synthesis of inflammatory factors that alter glutamate transporter function. ERK also further activates AMPARs and NMDARs in neurons. Nociception is further sensitized by the association of ATP and substance P with their respective receptors (P2X3) and neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R), as well as activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors and release of BDNF. Persistent presence of glutamate in the synapse eventually results in dysregulation of GLT1 and GLAST, crucial transporters of glutamate into astrocytes. Ongoing excitation can also induce ERK and JNK activation, resulting in release of several inflammatory factors.

As noxious pain is sustained, spinal sensitization creates transcriptional changes in the neurons of the dorsal horn that lead to altered function for extended periods. Mobilization of Ca2+ from internal stores results from persistent synaptic activity and leads to the release of glutamate, ATP, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-6, nitric oxide (NO), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). Activated astrocytes are also a source of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2), which induces pro-IL-1β cleavage and sustains astrocyte activation. In this chronic signaling pathway, p38 is activated as a result of IL-1β signaling, and there is a presence of chemokines that trigger their receptors to become active. In response to nerve damage, heat shock proteins (HSP) are released and can bind to their respective TLRs, leading to further activation.

Other pathologies

[edit]Other clinically significant pathologies involving astrocytes include astrogliosis and astrocytopathy. Examples of these include multiple sclerosis, anti-AQP4+ neuromyelitis optica, Rasmussen's encephalitis, Alexander disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.[63] Studies have shown that astrocytes may be implied in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease,[64][65] Parkinson's disease,[66] Huntington's disease, Stuttering[67] and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,[68] and in acute brain injuries, such as intracerebral hemorrhage [69] and traumatic brain injury.[70]

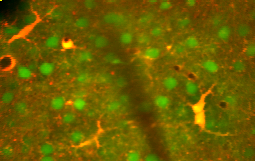

Gomori-positive astrocytes and brain dysfunction

[edit]A type of astrocyte with an aging-related pathology has been described over the last fifty years. Astrocytes of this subtype possess prominent cytoplasmic granules that are intensely stained by Gomori's chrome alum hematoxylin stain, and hence are termed Gomori-positive (GP) astrocytes. They can be found throughout the brain, but are by far the most abundant in the olfactory bulbs, medial habenula, dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, and in the dorsal medulla, just beneath the area postrema.[71]

Gomori-positive cytoplasmic granules are derived from damaged mitochondria engulfed within lysosomes.[72] Cytoplasmic granules contain undigested remnants of mitochondrial structures. These contents include heme-linked copper and iron atoms remaining from mitochondrial enzymes.[73] These chemical substances account for the pseudoperoxidase activity of Gomori-positive granules that can utilized to stain for these granules. Oxidative stress is believed to be cause of damage to these astrocytes.[74] However, the exact nature of this stress is uncertain.

Brain regions enriched in Gomori-positive astrocytes also contain a sub-population of specialized astrocytes that synthesize Fatty Acid Binding Protein 7 (FABP7). Indeed, astrocytes in the hypothalamus that synthesize FABP7 have also been shown to possess Gomori-positive granules.[75] Thus, a connection between these two glial features is apparent. Recent data have shown that astrocytes, but not neurons, possess the mitochondrial enzymes needed to metabolize fatty acids, and that the resulting oxidative stress can damage mitochondria.[76] Thus, an increased uptake and oxidation of fatty acids in glia containing FABP7 is likely to cause the oxidative stress and damage to mitochondria in these cells. Also, FABP proteins have recently been shown to interact with a protein called synuclein to cause mitochondrial damage.[77]

Possible roles in pathophysiology

[edit]Astrocytes can transfer mitochondria into adjacent neurons to improve neuronal function.[78] It is therefore plausible that the damage to astrocyte mitochondria seen in GP astrocytes could affect the activity of neurons.

A number of hypothalamic functions show declines in aging that may be related to GP astrocytes. For example, GP astrocytes are in close contact with neurons that make a neurotransmitter called dopamine in both the rat and human hypothalamus.[79] The dopamine produced by these neurons is carried to the nearby pituitary gland to inhibit the release of a hormone called prolactin from the pituitary. The activity of dopaminergic neurons declines during aging, leading to elevations in blood levels of prolactin that can provoke breast cancer.[80] An aging-associated change in astrocyte function might contribute to this change in dopaminergic activity.

FABP7+ astrocytes are in close contact with neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus that are responsive to a hormone called leptin that is produced by fat cells. Leptin-sensitive neurons regulate appetite and body weight. FABP7+ astrocytes regulate the responsiveness of these neurons to leptin. Mitochondrial damage in these astrocytes could thus alter the function of leptin-sensitive neurons and could contribute to an aging-associated dysregulation of feeding and body weight.[81]

GP astrocytes may also be involved in the hypothalamic regulation of overall glucose metabolism. Recent data show that astrocytes function as glucose sensors and exert a commanding influence upon neuronal reactivity to changes in extracellular glucose.[82] GP astrocytes possess high-capacity GLUT2-type glucose transporter proteins and appear to modulate the neuronal responses to glucose.[83] Hypothalamic cells monitor blood levels of glucose and exert an influence upon blood glucose levels via an altered input to autonomic circuits that innervate liver and muscle cells.

The importance of astrocytes in aging-related disturbances in glucose metabolism has been recently illustrated by studies of diabetic animals. A single infusion of a protein called fibroblast growth factor-1 into the hypothalamus has been shown to permanently normalize blood glucose levels in diabetic rodents. This remarkable cure of diabetes mellitus is mediated by astrocytes. The most prominent genes activated by FGF-1 treatment include the genes responsible for the synthesis of FABP6 and FABP7 by astrocytes.[84] These data confirm the importance of FABP7+ astrocytes for the control of blood glucose. Dysfunction of FABP7+/Gomori-positive astrocytes may contribute to the aging-related development of diabetes mellitus.

GP astrocytes are also present in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus in both rodent and human brains.[85] The hippocampus undergoes severe degenerative changes during aging in Alzheimer's disease. The reasons for these degenerative changes are currently being hotly debated. A recent study has shown that levels of glial proteins, and NOT neuronal proteins, are most abnormal in Alzheimer's disease. The glial protein most severely affected is FABP5.[86] Another study showed that 100% of hippocampal astrocytes that contain FABP7 also contain FABP5.[87] These data suggest that FABP7+/Gomori-positive astrocytes may play a role in Alzheimer's disease. An altered glial function in this region could compromise the function of dentate gyrus neurons and also the function of axons that terminate in the dentate gyrus. Many such axons originate in the lateral entorhinal cortex, which is the first brain region to show degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Astrocyte pathology in the hippocampus thus might make a contribution to the pathology of Alzheimer's disease.

Research

[edit]A study performed in November 2010 and published March 2011, was done by a team of scientists from the University of Rochester and University of Colorado School of Medicine. They did an experiment to attempt to repair trauma to the Central Nervous System of an adult rat by replacing the glial cells. When the glial cells were injected into the injury of the adult rat's spinal cord, astrocytes were generated by exposing human glial precursor cells to bone morphogenetic protein (bone morphogenetic protein is important because it is considered to create tissue architecture throughout the body). So, with the bone protein and human glial cells combined, they promoted significant recovery of conscious foot placement, axonal growth, and obvious increases in neuronal survival in the spinal cord laminae. On the other hand, human glial precursor cells and astrocytes generated from these cells by being in contact with ciliary neurotrophic factors, failed to promote neuronal survival and support of axonal growth at the spot of the injury.[88]

One study done in Shanghai had two types of hippocampal neuronal cultures: In one culture, the neuron was grown from a layer of astrocytes and the other culture was not in contact with any astrocytes, but they were instead fed a glial conditioned medium (GCM), which inhibits the rapid growth of cultured astrocytes in the brains of rats in most cases. In their results they were able to see that astrocytes had a direct role in Long-term potentiation with the mixed culture (which is the culture that was grown from a layer of astrocytes) but not in GCM cultures.[89]

Studies have shown that astrocytes play an important function in the regulation of neural stem cells. Research from the Schepens Eye Research Institute at Harvard shows the human brain to abound in neural stem cells, which are kept in a dormant state by chemical signals (ephrin-A2 and ephrin-A3) from the astrocytes. The astrocytes are able to activate the stem cells to transform into working neurons by dampening the release of ephrin-A2 and ephrin-A3.[90]

In a study published in a 2011 issue of Nature Biotechnology[91] a group of researchers from the University of Wisconsin reports that it has been able to direct embryonic and induced human stem cells to become astrocytes.

A 2012 study[92] of the effects of marijuana on short-term memories found that THC activates CB1 receptors of astrocytes which cause receptors for AMPA to be removed from the membranes of associated neurons.

A 2023 study[93] showed that astrocytes also play an active role in Alzheimer's disease. More specifically, when astrocytes became reactive they unleash the pathological effects of amyloid-beta on downstream tau phosphorylation and deposition, which very likely will lead to cognitive deterioration.

Classification

[edit]There are several different ways to classify astrocytes.

Lineage and antigenic phenotype

[edit]These have been established by classic work by Raff et al. in early 1980s on Rat optic nerves.

- Type 1: Antigenically Ran2+, GFAP+, FGFR3+, A2B5−, thus resembling the "type 1 astrocyte" of the postnatal day 7 rat optic nerve. These can arise from the tripotential glial restricted precursor cells (GRP), but not from the bipotential O2A/OPC (oligodendrocyte, type 2 astrocyte precursor, also called Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell) cells.

- Type 2: Antigenically A2B5+, GFAP+, FGFR3−, Ran 2−. These cells can develop in vitro from the either tripotential GRP (probably via O2A stage) or from bipotential O2A cells (which some people{{[94]}} think may in turn have been derived from the GRP) or in vivo when these progenitor cells are transplanted into lesion sites (but probably not in normal development, at least not in the rat optic nerve). Type 2 astrocytes are the major astrocytic component in postnatal optic nerve cultures that are generated by O2A cells grown in the presence of fetal calf serum but are not thought to exist in vivo.[95]

Anatomical classification

[edit]- Protoplasmic: found in grey matter and have many branching processes whose end-feet envelop synapses. Some protoplasmic astrocytes are generated by multipotent subventricular zone progenitor cells.[96][97]

- Gömöri-positive astrocytes. These are a subset of protoplasmic astrocytes that contain numerous cytoplasmic inclusions, or granules, that stain positively with Gömöri trichrome stain a chrome-alum hematoxylin stain. It is now known that these granules are formed from the remnants of degenerating mitochondria engulfed within lysosomes,[98] Some type of oxidative stress appears to be responsible for the mitochondrial damage within these specialized astrocytes. Gömöri-positive astrocytes are much more abundant within the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus and in the hippocampus than in other brain regions. They may have a role in regulating the response of the hypothalamus to glucose.[99][100]

- Fibrous: found in white matter and have long thin unbranched processes whose end-feet envelop nodes of Ranvier. Some fibrous astrocytes are generated by radial glia.[101][102][103][104][105]

Transporter/receptor classification

[edit]- GluT type: these express glutamate transporters (EAAT1/SLC1A3 and EAAT2/SLC1A2) and respond to synaptic release of glutamate by transporter currents. The function and availability of EAAT2 is modulated by TAAR1, an intracellular receptor in human astrocytes.[106]

- GluR type: these express glutamate receptors (mostly mGluR and AMPA type) and respond to synaptic release of glutamate by channel-mediated currents and IP3-dependent Ca2+ transients.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Suzuki, Yasuhiro; Sa, Qila; Ochiai, Eri; Mullins, Jeremi; Yolken, Robert; Halonen, Sandra K. (2014). "Cerebral Toxoplasmosis". Toxoplasma Gondii. Elsevier. pp. 755–96. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-396481-6.00023-4. ISBN 978-0-12-396481-6.

Astrocytes are the dominant glial cell in the brain and numerous studies indicate they are central to the intracerebral immune response to T. gondii in the brain.

- ^ a b Freeman, MR; Rowitch, DH (30 October 2013). "Evolving concepts of gliogenesis: a look way back and ahead to the next 25 years". Neuron. 80 (3): 613–23. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.034. PMC 5221505. PMID 24183014.

- ^ Verkhratsky A, Butt AM (2013). "Numbers: how many glial cells are in the brain?". Glial Physiology and Pathophysiology. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 93–96. ISBN 978-0-470-97853-5.

- ^ a b Wang, Hao; Kulas, Joshua A.; Ferris, Heather A.; Hansen, Scott B. (2020-10-14). "Regulation of beta-amyloid production in neurons by astrocyte-derived cholesterol". bioRxiv 2020.06.18.159632. doi:10.1101/2020.06.18.159632. S2CID 220044671.

- ^ a b Sloan SA, Barres BA (August 2014). "Mechanisms of astrocyte development and their contributions to neurodevelopmental disorders". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 27: 75–81. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2014.03.005. PMC 4433289. PMID 24694749.

- ^ "Role of Astrocytes in the Central Nervous System". Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ Fiacco TA, Agulhon C, McCarthy KD (October 2008). "Sorting out astrocyte physiology from pharmacology". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 49 (1): 151–74. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145602. PMID 18834310.

- ^ Fields RD, Araque A, Johansen-Berg H, Lim SS, Lynch G, Nave KA, et al. (October 2014). "Glial biology in learning and cognition". The Neuroscientist. 20 (5): 426–31. doi:10.1177/1073858413504465. PMC 4161624. PMID 24122821.

- ^ Venkatesh K, Srikanth L, Vengamma B, Chandrasekhar C, Sanjeevkumar A, Mouleshwara Prasad BC, Sarma PV (2013). "In vitro differentiation of cultured human CD34+ cells into astrocytes". Neurology India. 61 (4): 383–88. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.117615. PMID 24005729.

- ^ Koch, Timo; Vinje, Vegard; Mardal, Kent-André (20 March 2023). "Estimates of the permeability of extra-cellular pathways through the astrocyte endfoot sheath". Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 20 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/s12987-023-00421-8. PMC 10026447. PMID 36941607.

- ^ Attwell, David; Laughlin, Simon B. (2001). "An Energy Budget for Signaling in the Grey Matter of the Brain". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 21 (10): 1133–45. doi:10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. ISSN 0271-678X. PMID 11598490.

- ^ Harris, Julia J.; Jolivet, Renaud; Attwell, David (2012). "Synaptic Energy Use and Supply". Neuron. 75 (5): 762–77. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.019. ISSN 0896-6273. PMID 22958818. S2CID 14988407.

- ^ a b Barros, LF (2022). "How expensive is the astrocyte?". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 42 (5): 738–45. doi:10.1177/0271678x221077343. ISSN 0271-678X. PMC 9254036. PMID 35080185.

- ^ Rowitch DH, Kriegstein AR (November 2010). "Developmental genetics of vertebrate glial-cell specification". Nature. 468 (7321): 214–22. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..214R. doi:10.1038/nature09611. PMID 21068830. S2CID 573477.

- ^ Muroyama Y, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH, Rowitch DH (November 2005). "Specification of astrocytes by bHLH protein SCL in a restricted region of the neural tube". Nature. 438 (7066): 360–63. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..360M. doi:10.1038/nature04139. PMID 16292311. S2CID 4425462.

- ^ Hochstim C, Deneen B, Lukaszewicz A, Zhou Q, Anderson DJ (May 2008). "Identification of positionally distinct astrocyte subtypes whose identities are specified by a homeodomain code". Cell. 133 (3): 510–22. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.046. PMC 2394859. PMID 18455991.

- ^ Cakir T, Alsan S, Saybaşili H, Akin A, Ulgen KO (December 2007). "Reconstruction and flux analysis of coupling between metabolic pathways of astrocytes and neurons: application to cerebral hypoxia". Theoretical Biology & Medical Modelling. 4 (1) 48. doi:10.1186/1742-4682-4-48. PMC 2246127. PMID 18070347.

- ^ Kolb, Brian and Whishaw, Ian Q. (2008) Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology. Worth Publishers. 6th ed. ISBN 0716795868[page needed]

- ^ a b Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG (May 1999). "Tripartite synapses: glia, the unacknowledged partner". Trends in Neurosciences. 22 (5): 208–15. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01349-6. PMID 10322493. S2CID 7067935.

- ^ Reynolds, Gretchen (22 February 2012). "How Exercise Fuels the Brain". New York Times.

- ^ McDougal DH, Viard E, Hermann GE, Rogers RC (April 2013). "Astrocytes in the hindbrain detect glucoprivation and regulate gastric motility". Autonomic Neuroscience. 175 (1–2): 61–69. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2012.12.006. PMC 3951246. PMID 23313342.

- ^ Swaminathan N (1 October 2008). "Brain-scan mystery solved". Scientific American Mind: 7. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind1008-16.

- ^ Figley CR, Stroman PW (February 2011). "The role(s) of astrocytes and astrocyte activity in neurometabolism, neurovascular coupling, and the production of functional neuroimaging signals". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (4): 577–88. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07584.x. PMID 21314846. S2CID 9094771.

- ^ Santello M, Volterra A (January 2009). "Synaptic modulation by astrocytes via Ca2+-dependent glutamate release". Neuroscience. Mar. 158 (1): 253–59. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.039. PMID 18455880. S2CID 9719903.

- ^ Agulhon C, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD (March 2010). "Hippocampal short- and long-term plasticity are not modulated by astrocyte Ca2+ signaling". Science. 327 (5970): 1250–54. Bibcode:2010Sci...327.1250A. doi:10.1126/science.1184821. PMID 20203048. S2CID 14594882.

- ^ Walz W (April 2000). "Role of astrocytes in the clearance of excess extracellular potassium". Neurochemistry International. 36 (4–5): 291–300. doi:10.1016/S0197-0186(99)00137-0. PMID 10732996. S2CID 40064468.

- ^ Gabriel S, Njunting M, Pomper JK, Merschhemke M, Sanabria ER, Eilers A, et al. (November 2004). "Stimulus and potassium-induced epileptiform activity in the human dentate gyrus from patients with and without hippocampal sclerosis". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (46): 10416–30. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2074-04.2004. PMC 6730304. PMID 15548657.

- ^ Piet R, Vargová L, Syková E, Poulain DA, Oliet SH (February 2004). "Physiological contribution of the astrocytic environment of neurons to intersynaptic crosstalk". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (7): 2151–55. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.2151P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308408100. PMC 357067. PMID 14766975.

- ^ Pascual O, Casper KB, Kubera C, Zhang J, Revilla-Sanchez R, Sul JY, et al. (October 2005). "Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks". Science. 310 (5745): 113–16. Bibcode:2005Sci...310..113P. doi:10.1126/science.1116916. PMID 16210541. S2CID 36808788.

- ^ Parri R, Crunelli V (January 2003). "An astrocyte bridge from synapse to blood flow". Nature Neuroscience. 6 (1): 5–6. doi:10.1038/nn0103-5. PMID 12494240. S2CID 42872329.

- ^ Ishibashi T, Dakin KA, Stevens B, Lee PR, Kozlov SV, Stewart CL, Fields RD (March 2006). "Astrocytes promote myelination in response to electrical impulses". Neuron. 49 (6): 823–32. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.006. PMC 1474838. PMID 16543131.

- ^ a b Anderson MA, Burda JE, Ren Y, Ao Y, O'Shea TM, Kawaguchi R, et al. (April 2016). "Astrocyte scar formation aids central nervous system axon regeneration". Nature. 532 (7598): 195–200. Bibcode:2016Natur.532..195A. doi:10.1038/nature17623. PMC 5243141. PMID 27027288.

- ^ Potokar, Maja; Morita, Mitsuhiro; Wiche, Gerhard; Jorgačevski, Jernej (2020-07-02). "The Diversity of Intermediate Filaments in Astrocytes". Cells. 9 (7): 1604. doi:10.3390/cells9071604. ISSN 2073-4409. PMC 7408014. PMID 32630739.

- ^ Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE, Bennett FC, Bohlen CJ, Schirmer L, et al. (January 2017). "Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia". Nature. 541 (7638): 481–87. Bibcode:2017Natur.541..481L. doi:10.1038/nature21029. PMC 5404890. PMID 28099414.

- ^ Han X, Chen M, Wang F, Windrem M, Wang S, Shanz S, et al. (March 2013). "Forebrain engraftment by human glial progenitor cells enhances synaptic plasticity and learning in adult mice". Cell Stem Cell. 12 (3): 342–53. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.015. PMC 3700554. PMID 23472873.

- ^ Brancaccio M, Edwards MD, Patton AP, Smyllie NJ, Chesham JE, Maywood ES, Hastings MH (January 2019). "Cell-autonomous clock of astrocytes drives circadian behavior in mammals". Science. 363 (6423): 187–92. Bibcode:2019Sci...363..187B. doi:10.1126/science.aat4104. PMC 6440650. PMID 30630934.

- ^ a b c Nossenson N, Magal A, Messer H (2016). "Detection of stimuli from multi-neuron activity: Empirical study and theoretical implications". Neurocomputing. 174: 822–37. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2015.10.007.

- ^ a b Nossenson N (2013). Model Based Detection of a Stimulus Presence from Neurophysiological Signals (PDF). The Neiman Library of Exact Sciences & Engineering, Tel Aviv University: PhD diss, University of Tel-Aviv.

- ^ Cornell-Bell AH, Finkbeiner SM, Cooper MS, Smith SJ (January 1990). "Glutamate induces calcium waves in cultured astrocytes: long-range glial signaling". Science. 247 (4941): 470–73. Bibcode:1990Sci...247..470C. doi:10.1126/science.1967852. PMID 1967852.

- ^ Jahromi BS, Robitaille R, Charlton MP (June 1992). "Transmitter release increases intracellular calcium in perisynaptic Schwann cells in situ". Neuron. 8 (6): 1069–77. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(92)90128-Z. PMID 1351731. S2CID 6855190.

- ^ Verkhratsky A, Orkand RK, Kettenmann H (January 1998). "Glial calcium: homeostasis and signaling function". Physiological Reviews. 78 (1): 99–141. doi:10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.99. PMID 9457170. S2CID 823182.

- ^ a b Ebert U, Koch M (September 1997). "Acoustic startle-evoked potentials in the rat amygdala: effect of kindling". Physiology & Behavior. 62 (3): 557–62. doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(97)00018-8. PMID 9272664. S2CID 41925078.

- ^ a b Frot M, Magnin M, Mauguière F, Garcia-Larrea L (March 2007). "Human SII and posterior insula differently encode thermal laser stimuli". Cerebral Cortex. 17 (3): 610–20. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhk007. PMID 16614165.

- ^ a b Perlman, Ido. "The Electroretinogram: ERG by Ido Perlman – Webvision". webvision.med.utah.edu.

- ^ a b Tian GF, Azmi H, Takano T, Xu Q, Peng W, Lin J, et al. (September 2005). "An astrocytic basis of epilepsy". Nature Medicine. 11 (9): 973–81. doi:10.1038/nm1277. PMC 1850946. PMID 16116433.

- ^ Hertz L, Schousboe A, Boechler N, Mukerji S, Fedoroff S (February 1978). "Kinetic characteristics of the glutamate uptake into normal astrocytes in cultures". Neurochemical Research. 3 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1007/BF00964356. PMID 683409. S2CID 8626930.

- ^ Bennett MV, Contreras JE, Bukauskas FF, Sáez JC (November 2003). "New roles for astrocytes: gap junction hemichannels have something to communicate". Trends in Neurosciences. 26 (11): 610–17. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.008. PMC 3694339. PMID 14585601.

- ^ Newman EA (April 2001). "Propagation of intercellular calcium waves in retinal astrocytes and Müller cells". The Journal of Neuroscience. 21 (7): 2215–23. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02215.2001. PMC 2409971. PMID 11264297.

- ^ Parpura V, Haydon PG (July 2000). "Physiological astrocytic calcium levels stimulate glutamate release to modulate adjacent neurons". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (15): 8629–34. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.8629P. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.15.8629. PMC 26999. PMID 10900020.

- ^ a b López-Caamal F, Oyarzún DA, Middleton RH, García MR (May 2014). "Spatial Quantification of Cytosolic Ca2+ Accumulation in Nonexcitable Cells: An Analytical Study". IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics. 11 (3): 592–603. doi:10.1109/TCBB.2014.2316010. hdl:10261/121689. PMID 26356026.

- ^ a b Haydon PG (March 2001). "GLIA: listening and talking to the synapse" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2 (3): 185–93. doi:10.1038/35058528. PMID 11256079. S2CID 15777434.

- ^ "Lesser-known brain cells may be key to staying awake without cost to cognition, health". WSU Insider | Washington State University. 2023-08-17. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ De Ceglia, Roberta; Ledonne, Ada; Litvin, David Gregory; Lind, Barbara Lykke; Carriero, Giovanni; Latagliata, Emanuele Claudio; Bindocci, Erika; Di Castro, Maria Amalia; Savtchouk, Iaroslav; Vitali, Ilaria; Ranjak, Anurag; Congiu, Mauro; Canonica, Tara; Wisden, William; Harris, Kenneth; Mameli, Manuel; Mercuri, Nicola; Telley, Ludovic; Volterra, Andrea (6 September 2023). "Specialized astrocytes mediate glutamatergic gliotransmission in the CNS". Nature. 622 (7981): 120–29. Bibcode:2023Natur.622..120D. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06502-w. PMC 10550825. PMID 37674083.

- ^ Makin, Simon (2023-12-01). "Newfound Hybrid Brain Cells Send Signals like Neurons Do". Scientific American. Retrieved 2024-12-15.

- ^ "New type of brain cell discovered that acts like hybrid of two others". New Scientist. Retrieved 2024-12-15.

- ^ "New Hybrid Cell Discovery Shakes Up Neuroscience". Neuroscience News. 2023-09-06. Retrieved 2024-12-15.

- ^ a b c d Astrocytomas Archived 2012-04-05 at the Wayback Machine. International RadioSurgery Association (2010).

- ^ a b Astrocytoma Tumors. American Association of Neurological Surgeons (August 2005).

- ^ Barker AJ, Ullian EM (2008). "New roles for astrocytes in developing synaptic circuits". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 1 (2): 207–11. doi:10.4161/cib.1.2.7284. PMC 2686024. PMID 19513261.

- ^ Garrison CJ, Dougherty PM, Kajander KC, Carlton SM (November 1991). "Staining of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in lumbar spinal cord increases following a sciatic nerve constriction injury". Brain Research. 565 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(91)91729-K. PMID 1723019. S2CID 8251884.

- ^ Volterra A, Meldolesi J (August 2005). "Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: the revolution continues". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 6 (8): 626–40. doi:10.1038/nrn1722. PMID 16025096. S2CID 14457143.

- ^ Halassa MM, Fellin T, Haydon PG (February 2007). "The tripartite synapse: roles for gliotransmission in health and disease". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 13 (2): 54–63. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.12.005. PMID 17207662.

- ^ Sofroniew MV (November 2014). "Astrogliosis". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 7 (2) a020420. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a020420. PMC 4315924. PMID 25380660.

- ^ Söllvander S, Nikitidou E, Brolin R, Söderberg L, Sehlin D, Lannfelt L, Erlandsson A (May 2016). "Accumulation of amyloid-β by astrocytes result in enlarged endosomes and microvesicle-induced apoptosis of neurons". Molecular Neurodegeneration. 11 (1) 38. doi:10.1186/s13024-016-0098-z. PMC 4865996. PMID 27176225.

- ^ Bhat R, Crowe EP, Bitto A, Moh M, Katsetos CD, Garcia FU, et al. (2012-09-12). "Astrocyte senescence as a component of Alzheimer's disease". PLOS ONE. 7 (9) e45069. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745069B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045069. PMC 3440417. PMID 22984612.

- ^ Rostami J, Holmqvist S, Lindström V, Sigvardson J, Westermark GT, Ingelsson M, et al. (December 2017). "Human Astrocytes Transfer Aggregated Alpha-Synuclein via Tunneling Nanotubes". The Journal of Neuroscience. 37 (49): 11835–53. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0983-17.2017. PMC 5719970. PMID 29089438.

- ^ Han TU, Drayna D (August 2019). "Human GNPTAB stuttering mutations engineered into mice cause vocalization deficits and astrocyte pathology in the corpus callosum". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (35): 17515–24. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11617515H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1901480116. PMC 6717282. PMID 31405983. S2CID 6717282.

- ^ Maragakis NJ, Rothstein JD (December 2006). "Mechanisms of Disease: astrocytes in neurodegenerative disease". Nature Clinical Practice. Neurology. 2 (12): 679–89. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0355. PMID 17117171. S2CID 16188129.

- ^ Ren H, Han R, Chen X, Liu X, Wan J, Wang L, Yang X, Wang J (May 2020). "Potential therapeutic targets for intracerebral hemorrhage-associated inflammation: An update". J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 40 (9): 1752–68. doi:10.1177/0271678X20923551. PMC 7446569. PMID 32423330.

- ^ Qin D, Wang J, Le A, Wang TJ, Chen X, Wang J (April 2021). "Traumatic Brain Injury: Ultrastructural Features in Neuronal Ferroptosis, Glial Cell Activation and Polarization, and Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown". Cells. 10 (5): 1009. doi:10.3390/cells10051009. PMC 8146242. PMID 33923370.

- ^ Keefer, Donald A.; Christ, Jacob F. (November 1976). "Distribution of endogenous diaminobenzidine-staining cells in the normal rat brain". Brain Research. 116 (2): 312–16. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(76)90909-4. PMID 61791. S2CID 3069004.

- ^ Brawer, James R.; Stein, Robert; Small, Lorne; Cissé, Soriba; Schipper, Hyman M. (November 1994). "Composition of Gomori-positive inclusions in astrocytes of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: Gomori-Positive Inclusions in Astrocytes". The Anatomical Record. 240 (3): 407–15. doi:10.1002/ar.1092400313. PMID 7825737. S2CID 20052516.

- ^ Sullivan, Brendan; Robison, Gregory; Pushkar, Yulia; Young, John K.; Manaye, Kebreten F. (January 2017). "Copper accumulation in rodent brain astrocytes: A species difference". Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 39: 6–13. Bibcode:2017JTEMB..39....6S. doi:10.1016/j.jtemb.2016.06.011. PMC 5141684. PMID 27908425.

- ^ Schipper, HM (1993). "Cysteamine gliopathy in situ: a cellular stress model for the biogenesis of astrocytic inclusions". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 52 (4): 399–410. doi:10.1097/00005072-199307000-00007. PMID 8394877. S2CID 42421463.

- ^ Young, John K.; Baker, James H.; Müller, Thomas (March 1996). "Immunoreactivity for brain-fatty acid binding protein in gomori-positive astrocytes". Glia. 16 (3): 218–226. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199603)16:3<218::AID-GLIA4>3.0.CO;2-Y. ISSN 0894-1491. PMID 8833192. S2CID 9757285.

- ^ Schmidt, S.P.; Corydon, T.J.; Pedersen, C.B.; Bross, P.; Gregersen, N. (June 2010). "Misfolding of short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase leads to mitochondrial fission and oxidative stress". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 100 (2): 155–62. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.03.009. PMID 20371198.

- ^ Cheng, A (2021). "Impact of fatty acid-binding proteins in α-Synuclein-induced mitochondrial injury in synucleinopathy". Biomedicines. 9 (5): 560. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9050560. PMC 8156290. PMID 34067791.

- ^ English, Krystal; Shepherd, Andrew; Uzor, Ndidi-Ese; Trinh, Ronnie; Kavelaars, Annemieke; Heijnen, Cobi J. (December 2020). "Astrocytes rescue neuronal health after cisplatin treatment through mitochondrial transfer". Acta Neuropathologica Communications. 8 (1): 36. doi:10.1186/s40478-020-00897-7. ISSN 2051-5960. PMC 7082981. PMID 32197663.

- ^ Young, J. K.; McKenzie, J. C.; Baker, J. H. (February 1990). "Association of iron-containing astrocytes with dopaminergic neurons of the arcuate nucleus". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 25 (2): 204–13. doi:10.1002/jnr.490250208. ISSN 0360-4012. PMID 2319629. S2CID 39851598.

- ^ Reymond, Marianne J.; Donda, Alena; Lemarchand-Béraud, Thérèse (1989). "Neuroendocrine Aspects of Aging: Experimental Data". Hormone Research. 31 (1–2): 32–38. doi:10.1159/000181083. ISSN 1423-0046. PMID 2656467.

- ^ Yasumoto, Yuki; Miyazaki, Hirofumi; Ogata, Masaki; Kagawa, Yoshiteru; Yamamoto, Yui; Islam, Ariful; Yamada, Tetsuya; Katagiri, Hideki; Owada, Yuji (December 2018). "Glial Fatty Acid-Binding Protein 7 (FABP7) Regulates Neuronal Leptin Sensitivity in the Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus". Molecular Neurobiology. 55 (12): 9016–28. doi:10.1007/s12035-018-1033-9. ISSN 0893-7648. PMID 29623545. S2CID 4632807.

- ^ Rogers, Richard C.; McDougal, David H.; Ritter, Sue; Qualls-Creekmore, Emily; Hermann, Gerlinda E. (2018-07-01). "Response of catecholaminergic neurons in the mouse hindbrain to glucoprivic stimuli is astrocyte dependent". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 315 (1): R153–64. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00368.2017. ISSN 0363-6119. PMC 6087883. PMID 29590557.

- ^ Young, John K.; McKenzie, James C. (November 2004). "GLUT2 Immunoreactivity in Gomori-positive Astrocytes of the Hypothalamus". Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 52 (11): 1519–24. doi:10.1369/jhc.4A6375.2004. ISSN 0022-1554. PMC 3957823. PMID 15505347.

- ^ Brown, Jenny M.; Bentsen, Marie A.; Rausch, Dylan M.; Phan, Bao Anh; Wieck, Danielle; Wasanwala, Huzaifa; Matsen, Miles E.; Acharya, Nikhil; Richardson, Nicole E.; Zhao, Xin; Zhai, Peng (September 2021). "Role of hypothalamic MAPK/ERK signaling and central action of FGF1 in diabetes remission". iScience. 24 (9) 102944. Bibcode:2021iSci...24j2944B. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102944. PMC 8368994. PMID 34430821.

- ^ Young, JK (2020). "Neurogenesis makes a crucial contribution to the neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease Reports. 4 (1): 365–71. doi:10.3233/ADR-200218. PMC 7592839. PMID 33163897.

- ^ Johnson, Erik C. B.; Dammer, Eric B.; Duong, Duc M.; Ping, Lingyan; Zhou, Maotian; Yin, Luming; Higginbotham, Lenora A.; Guajardo, Andrew; White, Bartholomew; Troncoso, Juan C.; Thambisetty, Madhav (May 2020). "Large-scale proteomic analysis of Alzheimer's disease brain and cerebrospinal fluid reveals early changes in energy metabolism associated with microglia and astrocyte activation". Nature Medicine. 26 (5): 769–80. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0815-6. ISSN 1078-8956. PMC 7405761. PMID 32284590.

- ^ Matsumata, Miho; Sakayori, Nobuyuki; Maekawa, Motoko; Owada, Yuji; Yoshikawa, Takeo; Osumi, Noriko (2012-07-01). "The Effects of Fabp7 and Fabp5 on Postnatal Hippocampal Neurogenesis in the Mouse". Stem Cells. 30 (7): 1532–43. doi:10.1002/stem.1124. ISSN 1066-5099. PMID 22581784. S2CID 13531289.

- ^ Davies SJ, Shih CH, Noble M, Mayer-Proschel M, Davies JE, Proschel C (March 2011). Combs C (ed.). "Transplantation of specific human astrocytes promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury". PLOS ONE. 6 (3) e17328. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617328D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017328. PMC 3047562. PMID 21407803.

- ^ Yang Y, Ge W, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Shen W, Wu C, et al. (December 2003). "Contribution of astrocytes to hippocampal long-term potentiation through release of D-serine". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (25): 15194–99. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10015194Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.2431073100. PMC 299953. PMID 14638938.

- ^ Jiao JW, Feldheim DA, Chen DF (June 2008). "Ephrins as negative regulators of adult neurogenesis in diverse regions of the central nervous system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (25): 8778–83. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.8778J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708861105. PMC 2438395. PMID 18562299.

- ^ Krencik R, Weick JP, Liu Y, Zhang ZJ, Zhang SC (May 2011). "Specification of transplantable astroglial subtypes from human pluripotent stem cells". Nature Biotechnology. 29 (6): 528–34. doi:10.1038/nbt.1877. PMC 3111840. PMID 21602806.. Lay summary: Human Astrocytes Cultivated From Stem Cells In Lab Dish by U of Wisconsin Researchers. sciencedebate.com (22 May 2011)

- ^ Han J, Kesner P, Metna-Laurent M, Duan T, Xu L, Georges F, et al. (March 2012). "Acute cannabinoids impair working memory through astroglial CB1 receptor modulation of hippocampal LTD". Cell. 148 (5): 1039–50. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.037. PMID 22385967.

- ^ Bellaver B, Povala G, Ferreira PL, Ferrari-Souza JP, Leffa DT, Lussier FZ, et al. (May 2023). "Astrocyte reactivity influences amyloid-β effects on tau pathology in preclinical Alzheimer's disease". Nature Medicine. 29 (7): 1775–81. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02380-x. PMC 10353939. PMID 37248300.

- ^ Gregori N, Pröschel C, Noble M, Mayer-Pröschel M (January 2002). "The tripotential glial-restricted precursor (GRP) cell and glial development in the spinal cord: generation of bipotential oligodendrocyte-type-2 astrocyte progenitor cells and dorsal-ventral differences in GRP cell function". The Journal of Neuroscience. 22 (1): 248–56. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00248.2002. PMC 6757619. PMID 11756508.

- ^ Fulton BP, Burne JF, Raff MC (December 1992). "Visualization of O-2A progenitor cells in developing and adult rat optic nerve by quisqualate-stimulated cobalt uptake". The Journal of Neuroscience. 12 (12): 4816–33. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04816.1992. PMC 6575772. PMID 1281496.

- ^ Levison SW, Goldman JE (February 1993). "Both oligodendrocytes and astrocytes develop from progenitors in the subventricular zone of postnatal rat forebrain". Neuron. 10 (2): 201–12. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(93)90311-E. PMID 8439409. S2CID 1428135.

- ^ Zerlin M, Levison SW, Goldman JE (November 1995). "Early patterns of migration, morphogenesis, and intermediate filament expression of subventricular zone cells in the postnatal rat forebrain". The Journal of Neuroscience. 15 (11): 7238–49. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07238.1995. PMC 6578041. PMID 7472478.

- ^ Brawer JR, Stein R, Small L, Cissé S, Schipper HM (November 1994). "Composition of Gomori-positive inclusions in astrocytes of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus". The Anatomical Record. 240 (3): 407–15. doi:10.1002/ar.1092400313. PMID 7825737. S2CID 20052516.

- ^ Young JK, McKenzie JC (November 2004). "GLUT2 immunoreactivity in Gomori-positive astrocytes of the hypothalamus". The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 52 (11): 1519–24. doi:10.1369/jhc.4A6375.2004. PMC 3957823. PMID 15505347.

- ^ Marty N, Dallaporta M, Foretz M, Emery M, Tarussio D, Bady I, et al. (December 2005). "Regulation of glucagon secretion by glucose transporter type 2 (glut2) and astrocyte-dependent glucose sensors". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 115 (12): 3545–53. doi:10.1172/jci26309. PMC 1297256. PMID 16322792.

- ^ Choi BH, Lapham LW (June 1978). "Radial glia in the human fetal cerebrum: a combined Golgi, immunofluorescent and electron microscopic study". Brain Research. 148 (2): 295–311. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(78)90721-7. PMID 77708. S2CID 3058148.

- ^ Schmechel DE, Rakic P (June 1979). "A Golgi study of radial glial cells in developing monkey telencephalon: morphogenesis and transformation into astrocytes". Anatomy and Embryology. 156 (2): 115–52. doi:10.1007/BF00300010. PMID 111580. S2CID 40494903.

- ^ Misson JP, Edwards MA, Yamamoto M, Caviness VS (November 1988). "Identification of radial glial cells within the developing murine central nervous system: studies based upon a new immunohistochemical marker". Brain Research. Developmental Brain Research. 44 (1): 95–108. doi:10.1016/0165-3806(88)90121-6. PMID 3069243.

- ^ Voigt T (November 1989). "Development of glial cells in the cerebral wall of ferrets: direct tracing of their transformation from radial glia into astrocytes". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 289 (1): 74–88. doi:10.1002/cne.902890106. PMID 2808761. S2CID 24449457.

- ^ Goldman SA, Zukhar A, Barami K, Mikawa T, Niedzwiecki D (August 1996). "Ependymal/subependymal zone cells of postnatal and adult songbird brain generate both neurons and nonneuronal siblings in vitro and in vivo". Journal of Neurobiology. 30 (4): 505–20. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199608)30:4<505::AID-NEU6>3.0.CO;2-7. PMID 8844514.

- ^ Cisneros IE, Ghorpade A (October 2014). "Methamphetamine and HIV-1-induced neurotoxicity: role of trace amine associated receptor 1 cAMP signaling in astrocytes". Neuropharmacology. 85: 499–507. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.011. PMC 4315503. PMID 24950453.

Moreover, TAAR1 overexpression significantly decreased EAAT-2 levels and glutamate clearance that were further reduced by METH. Taken together, our data show that METH treatment activated TAAR1 leading to intracellular cAMP in human astrocytes and modulated glutamate clearance abilities. Furthermore, molecular alterations in astrocyte TAAR1 levels correspond to changes in astrocyte EAAT-2 levels and function.

Further reading

[edit]- White FA, Jung H, Miller RJ (December 2007). "Chemokines and the pathophysiology of neuropathic pain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (51): 20151–58. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10420151W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0709250104. PMC 2154400. PMID 18083844.

- Milligan ED, Watkins LR (January 2009). "Pathological and protective roles of glia in chronic pain". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 10 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1038/nrn2533. PMC 2752436. PMID 19096368.

- Watkins LR, Milligan ED, Maier SF (August 2001). "Glial activation: a driving force for pathological pain". Trends in Neurosciences. 24 (8): 450–55. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01854-3. PMID 11476884. S2CID 6822068.

- Freeman MR (November 2010). "Specification and morphogenesis of astrocytes". Science. 330 (6005): 774–78. Bibcode:2010Sci...330..774F. doi:10.1126/science.1190928. PMC 5201129. PMID 21051628.

- Verkhratsky, A.; Butt, A.M. (2013). "Numbers: how many glial cells are in the brain?". Glial Physiology and Pathophysiology. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 93–96. ISBN 978-0-470-97853-5.

- Ren H, Han R, Chen X, Liu X, Wan J, Wang L, Yang X, Wang J (May 2020). "Potential therapeutic targets for intracerebral hemorrhage-associated inflammation: An update". J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 40 (9): 1752–68. doi:10.1177/0271678X20923551. PMC 7446569. PMID 32423330.