Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Therocephalia

View on Wikipedia

| Therocephalians Temporal range: Middle Permian–Middle Triassic Possible descendant taxon Cynodontia survives to present

| |

|---|---|

| |

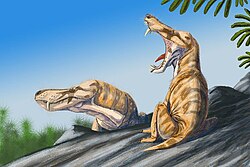

| Life restoration of two representatives of the early therocephalian genus Alopecognathus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | Eutheriodontia |

| Clade: | †Therocephalia Broom, 1903 |

| Subtaxa | |

Therocephalia is an extinct group of therapsids (mammals and their close extinct relatives) from the Permian and Triassic periods. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of their teeth, suggest that they were carnivores. Like other non-mammalian synapsids, therocephalians were once described as "mammal-like reptiles". Therocephalia is the group most closely related to the cynodonts, which gave rise to the mammals. Indeed, it had been proposed that therocephalians themselves may have given rise to the cynodonts, and therefore that therocephalians as recognised are paraphyletic in relation to cynodonts and so not a clade. Conventionally, however, Therocephalia is regarded as the sister clade of Cynodontia, together forming the clade Eutheriodontia.

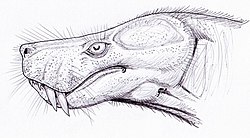

The close relationship of Therocephalia to Cynodontia takes evidence in a variety of skeletal features. Most notable is that the skull roof is narrowed between two enlarged temporal fenestra, allowing for expansive jaw musculature. At the same time, derived therocephalians also share a number of mammalian traits with cynodonts that evolved convergently, including a secondary palate, loss of the postorbital bar behind the eye and developing multi-cusped cheek teeth for herbivory. Other therocephalians retained simpler teeth for a carnivorous diet, often with large canines and sometimes a reduction or even total loss of the postcanine teeth. Such forms include genera that have even suggested to have possessed a venomous bite (namely Euchambersia), which would make therocephalians the oldest tetrapods known to have evolved this characteristic.

The fossils of therocephalians are most numerous in the Karoo of South Africa, but have also been found in Russia, China, Tanzania, Zambia, and Antarctica. Early therocephalian fossils discovered in Middle Permian deposits of South Africa support a Gondwanan origin for the group, which seems to have spread quickly across the supercontinent Pangaea. Although most therocephalian lineages died out during the Permian–Triassic extinction event, a few representatives of the subgroup Eutherocephalia survived into the ensuing Triassic period. However, only the cynodont-like subgroup Bauriamorpha survived past the Early Triassic and the last therocephalians became extinct by the early Middle Triassic, possibly due to climate change, along with competition with cynodonts and various groups of reptiles — mostly archosaurs and their close relatives, including archosauromorphs and archosauriforms.

Anatomy and physiology

[edit]

Like the Gorgonopsia and many cynodonts, most therocephalians were presumably carnivores. The earlier therocephalians were, in many respects, as primitive as the gorgonopsians, but they did show certain advanced features. There is an enlargement of the temporal opening for broader jaw adductor muscle attachment and a reduction of the phalanges (finger and toe bones) to the mammalian phalangeal formula. The presence of an incipient secondary palate in advanced therocephalians is another feature shared with mammals. The discovery of maxilloturbinal ridges in forms such as the primitive therocephalian Glanosuchus, suggests that at least some therocephalians may have been warm-blooded.[1]

The later therocephalians included the advanced Baurioidea, which carried some theriodont characteristics to a high degree of specialization. For instance, small baurioids and the herbivorous Bauria did not have an ossified postorbital bar separating the orbit from the temporal opening—a condition typical of primitive mammals. These and other advanced features led to the long-held opinion, now rejected, that the ictidosaurs and even some early mammals arose from a baurioid therocephalian stem. Mammalian characteristics such as this seem to have evolved in parallel among a number of different therapsid groups, even within Therocephalia.[1]

Several more specialized lifestyles have been suggested for some therocephalians. Many small forms, like ictidosuchids, have been interpreted as aquatic animals. Evidence for aquatic lifestyles includes sclerotic rings that may have stabilized the eye under the pressure of water and strongly developed cranial joints, which may have supported the skull when consuming large fish and aquatic invertebrates. One therocephalian, Nothogomphodon, had large sabre-like canine teeth and may have fed on large animals, including other therocephalians. Other therocephalians such as bauriids and nanictidopids have wide teeth with many ridges similar to those of mammals, and may have been herbivores.[2]

Many small therocephalians have small pits on their snouts that probably supported vibrissae (whiskers). In 1994, the Russian paleontologist Leonid Tatarinov proposed that these pits were part of an electroreception system in aquatic therocephalians.[3] However, it is more likely that these pits are enlarged versions of the ones thought to support whiskers, or holes for blood vessels in a fleshy lip.[2] The genera Euchambersia and Ichibengops, dating from the Lopingian, particularly attract the attention of paleontologists, because the fossil skulls attributed to them have some structures which suggests that these two animals had organs for distributing venom.[4][5]

Classification

[edit]

The therocephalians evolved as one of several lines of non-mammalian therapsids, and have a close relationship to the cynodonts, which includes mammals and their ancestors. They are broadly regarded as the sister group to cynodonts by most modern researchers, united together as the clade Eutheriodontia. However, some researchers have proposed that therocephalians are themselves ancestral to cynodonts, which would render therocephalians cladistically paraphyletic relative to cynodonts. Historically, cynodonts are often proposed to descend from (or are closest to) the therocephalian family Whaitsiidae under this hypothesis, however a 2024 study instead found support for a sister relationship between cynodonts and Eutherocephalia.[6] The oldest known therocephalians first appear in the fossil record at the same time as other major therapsid groups, including the Gorgonopsia, which they resemble in many primitive features. For example, many early therocephalians possess long canine teeth similar to those of gorgonopsians. The therocephalians, however, outlasted the gorgonopsians, persisting into the early-Middle Triassic period as small weasel-like carnivores and cynodont-like herbivores.[7]

While common ancestry with cynodonts (and, thus, mammals) accounts for many similarities between these groups, some scientists believe that other similarities may be better attributed to convergent evolution, such as the loss of the postorbital bar in some forms, a mammalian phalangeal formula, and some form of a secondary palate in most taxa. Therocephalians and cynodonts both survived the Permian-Triassic mass extinction; but, while therocephalians soon became extinct, cynodonts underwent rapid diversification. Therocephalians experienced a decreased rate of cladogenesis, meaning that few new groups appeared after the extinction. Most Triassic therocephalian lineages originated in the Late Permian, and lasted for only a short period of time in the Triassic,[8] going extinct during the late Anisian.[9]

Taxonomy

[edit]

Therocephalia was named by Robert Broom in 1903 as a new order to divide Theriodontia (then essentially containing all known carnivorous Permian and Triassic "mammal-like reptiles") into the "primitive" Permian forms, Therocephalia, and more mammal-like Triassic forms, Cynodontia,[a] based on the anatomy of their palates and the occipital condyle. Broom's Therocephalia was based primarily on Scylacosaurus (effectively the type genus of Therocephalia)[11] and Ictidosuchus, but differs strongly from modern classifications by also including various genera now recognised as gorgonopsians (a group Broom did not recognise as warranting distinction) such as Gorgonops and Aelurosaurus, and even what are now dinocephalians (e.g. Titanosuchus).[12]

From 1903 to 1907 Broom named and recognised more therocephalian genera, including several genera that are now non-therocephalian, mostly gorgonopsians, and even the anomodont Galechirus.[13] The latter's inclusion highlights Broom's view at the time of therocephalians as a 'primitive' order of therapsids and ancestral to the others, with anomodonts suggested to be descended from a therocephalian-like ancestor such as Galechirus.[14][15] Although his classification pre-dates cladistic terminology, Broom effectively conceived Therocephalia to be inherently paraphyletic from the beginning, giving rise to more 'advanced' therapsid groups. By 1908 he considered Galechirus and some other non-therocephalians inclusion in the group to be doubtful, including members of Gorgonopsia which he reinstated as a valid group in 1913. Nonetheless, for many decades after there was still confusion from him and other researchers over which genera belonged to which group. The group's rank also varied from order, suborder and infraorder depending on authors' preferred therapsid systematics.[11]

At the same time, the small 'advanced' therocephalians now classified under Baurioidea were often regarded as belonging to their own subgroup of therapsids distinct from therocephalians, the Bauriamorpha.[16] Bauriamorphs were classified separately from therocephalians for many decades, though were often inferred to have evolved from therocephalians in parallel with cynodonts, each typically from different therocephalian stock.[11] The inclusion of baurioids as deeply nested within Therocephalia was only firmly established in the 1980s, namely by Kemp (1982) and Hopson and Barghusen (1986).[17][18]

Various therocephalian subgroups and clades have been proposed since the group was named, although their contents and nomenclature have often been highly unstable and some previously recognized therocephalian clades have turned out to be artificial or based upon dubious taxa. This has led to some prevalent names in therocephalian literature, sometimes in use for decades, being replaced by lesser-known names that hold priority. For example, the Scaloposauridae was based on fossils with mostly juvenile characteristics and is likely represented by immature specimens from other disparate therocephalian families.

In another example, the name "Pristerognathidae" was extensively used for a group of basal therocephalians for much of the 20th century, but it has since been recognised that the name Scylacosauridae holds precedent for this group. Furthermore, the scope of "Pristerognathidae" was unstable and variably was limited to an individual subgroup of early therocephalians (alongside others such as Lycosuchidae, Alopecodontidae, and Ictidosauridae) to encompassing the entirety of early therocephalians.[11] Similarly, various names have been used for therocephalians corresponding to the family Adkidnognathidae in 20th century literature, including Annatherapsididae, Euchambersiidae (the oldest available name) and Moschorhinidae, and members have often had a confused relationship to whaitsiids. Consensus on the name and contents of Akidnognathidae was only achieved in the 21st century, asserting that a family-level group is established on the oldest referable genus and thus Akidnognathidae takes precedent for this group of non-whaitsioid eutherocephalians.[16]

On the other hand, some groups previously thought to be artificial have turned out to be valid. The aberrant therocephalian family Lycosuchidae, once identified by the presence of multiple functional caniniform teeth, was proposed to represent an unnatural group based on a study of canine replacement in early therocephalians by van den Heever in 1980 and its members referred to "Pristerognathidae".[19] However, subsequent examination by van den Heever and later analyses exposed additional synapomorphies supporting the monophyly of this group (including delayed caniniform replacement), and Lycosuchidae is currently considered a valid basal clade within Therocephalia.[20] However, most genera included in the group have since been declared dubious, and it now only includes Lycosuchus and Simorhinella.[21]

Modern therocephalian taxonomy is instead based upon phylogenetic analyses of therocephalian species, which consistently recognises two groups of early therocephalians (the Lycosuchidae and Scylacosauridae) while all other more derived therocephalians form the clade Eutherocephalia. Most phylogenetic analyses have found scylacosaurids to be closer to eutherocephalians than to lycosuchids, and so have been united in the clade Scylacosauria, but alternatively the two early families could be each other's sister taxa. Such a grouping has been referred to as the Pristerosauria, originally defined to include "pristerognathids" and various other therocephalian families by Lieuwe Dirk Boonstra in 1953 and redefined by Hopson and Barghusen in 1986 as the parent taxon to "Pristerognathidae", effectively uniting all primitive therocephalians (including lycosuchids).[18] In 1987, van den Heever argued against this possibility in favour of Scylacosauria, and discouraged the use of Pristerosauria for this reason and its connotations of deriving from "Pristerognathidae".[11] Most subsequent phylogenetic analyses have borne out this result, but an analysis from 2024 has recovered a clade uniting Scylacosauridae + Lycosuchidae to the exclusion of Eutherocephalia.[6]

Within Eutherocephalia, major clades corresponding to the families Akidnognathidae, Chthonosauridae, Hofmeyriidae, Whaitsiidae are recognised, along with various subclades grouped under Baurioidea. However, while individual groups of therocephalians are broadly recognised as valid, the interrelationships between them are often poorly supported.[22][23][24] As such, there are few higher-level named clades uniting the multiple subclades, with the exceptions of Whaitsiioidea (uniting Hofmeyriidae and Whaitsiidae) and Baurioidea.

Phylogeny

[edit]Early phylogenetic analyses of therocephalians, such as that of Hopson and Barghusen (1986) and van den Heever (1994), recovered and validated many of the therocephalian subtaxa mentioned above in a phylogenetic context. However, the higher-level relationships were difficult to resolve, particularly between the subclades of Eutherocephalia (i.e. Hofmeyriidae, Akidnognathidae, Whaitsiidae and Baurioidea). For example, Hopson and Barghusen (1986) could only recover Eutherocephalia as an unresolved polytomy.[18] Despite these shortcomings, subsequent discussions of therocephalian relationships relied almost exclusively on these analyses.[16] Later analyses focused on the relationships of early cynodonts, namely Abdala (2007) and Botha et al. (2007), included some therocephalian taxa and supported the existence of Eutherocephalia, but also found cynodonts to be the sister taxon to the whaitsiid therocephalian Theriognathus and thus rendering Therocephalia paraphyletic.[25][26]

Later phylogenetic analyses of therocephalians, initiated by Huttenlocker (2009), emphasise using a broader selection of therocephalian taxa and characters. Such analyses have reinforced Therocephalia as a sister clade to cynodonts, and the monophyly of Therocephalia has been supported by subsequent researchers.[16][7]

Below is a cladogram modified from an analysis published by Christian A. Sidor, Zoe. T Kulik and Adam K. Huttenlocker in 2022, simplified to illustrate the relationships of the major recognised therocephalian subclades.[27] It is based on the data matrix first published by Huttenlocker et al. (2011),[8] and represents the broad topologies found by other iterations of this dataset, such as Sigurdsen et al. (2012), Huttenlocker et al. (2014), and Liu and Abdala (2022).[28][29][22] An example of the lability of these relationships is demonstrated by Liu and Abdala (2023), who recovered an alternative topology with Chthonosauridae nested deeply within Akidnognathidae.[30] Relationships are not shown within bolded terminal clades on the cladogram below.

| Therapsida |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Below is a cladogram modified from Pusch et al. (2024) analysing the relationships of therocephalians and early cynodonts. Their analysis focused on including endocranial characteristics to help resolve the relations of therocephalians and cynodonts to supplement previous analyses that relied almost entirely on superficial cranial and dental characteristics that are subject to convergent evolution, and as such only includes taxa with available applicable data. Of these, only four therocephalians could be included. However, they each represent four major groups within therocephalian phylogeny: the two 'basal therocephalians' Lycosuchus (Lycosuchidae) and Alopecognathus (Scylacosauridae) and two derived members of Eutherocephalia, Olivierosuchus (Akidnognathidae) and Theriognathus (Whaitsiidae).[6]

Notably, their analyses consistently found cynodonts and eutherocephalians to be sister taxa, with the basal therocephalians Lycosuchus and scylacosaurids in a more basal position, rendering therocephalians as they are traditionally conceived paraphyletic. This differs from previous proposals of a paraphyletic Therocephalia which typically regarded cynodonts as being closest to derived whaitsiid therocephalians.[6]

|

Traditional therocephalians |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Broom initially retained the name Theriodontia for these "higher types", only separating out the therocephalians at first, but by 1908 he reflected this would cause confusion and reinstated Cynodontia in its place, dropping Theriodontia all together.[10] Theriodontia has since been re-defined cladistically as the clade containing gorgonopsians, therocephalians and cynodonts.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Rubidge, B.S.; Sidor, C.A. (2001). "Evolutionary patterns among Permo-Triassic therapsids" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 32: 449–480. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114113. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-21.

- ^ a b Ivakhnenko, M.F. (2011). "Permian and Triassic therocephals (Eutherapsida) of Eastern Europe". Paleontological Journal. 45 (9): 981–1144. doi:10.1134/S0031030111090012. S2CID 128958135.

- ^ Tatarinov, L.P. (1994). "On the preservation of rudimentary rostral tubular complex of crossopterygians in theriodonts and on possible development of the electroreceptor systems in some members of this group". Doklady Akademii Nauk. 338 (2): 278–281.

- ^ Benoit, J.; Norton, L.A.; Manger, P.R.; Rubidge, B.S. (2017). "Reappraisal of the envenoming capacity of Euchambersia mirabilis (Therapsida, Therocephalia) using μCT-scanning techniques". PLOS ONE. 12 (2) e0172047. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1272047B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172047. PMC 5302418. PMID 28187210.

- ^ Field Museum (August 13, 2015). "Prehistoric carnivore dubbed 'scarface' discovered in Zambia" (Press release). Science Daily.

- ^ a b c d Pusch, L. C.; Kammerer, C. F.; Fröbisch, J. (2024). "The origin and evolution of Cynodontia (Synapsida, Therapsida): Reassessment of the phylogeny and systematics of the earliest members of this clade using 3D-imaging technologies". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25394. PMID 38444024.

- ^ a b Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Kammerer, Christian F. (2018). "Non-Mammalian synapsids: the deep roots of the mammalian family tree". In Zachos, Frank E.; Asher, Robert J. (eds.). Mammalian Evolution, Diversity and Systematics. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 160–162. ISBN 978-3-11-027590-2.

- ^ a b Huttenlocker, A.K.; Sidor, C.A.; Smith, R.M.H. (2011). "A new specimen of Promoschorhynchus (Therapsida: Therocephalia: Akidnognathidae) from the Lower Triassic of South Africa and its implications for theriodont survivorship across the Permo-Triassic boundary". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (2): 405–421. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.546720. S2CID 129242450.

- ^ Grunert, Henrik Richard; Brocklehurst, Neil; Fröbisch, Jörg (25 March 2019). "Diversity and Disparity of Therocephalia: Macroevolutionary Patterns through Two Mass Extinctions". Scientific Reports. 9 (5063): 5063. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.5063G. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41628-w. PMC 6433905. PMID 30911058.

- ^ Broom, R. (1908). "On the inter-relationships of the known Therocephalian genera". Annals of the South African Museum. 4 (Pt. 8): 369–372.

- ^ a b c d e Van den Heever, J. (1987). The comparative and functional cranial morphology of the early Therocephalia (Amniota: Therapsida) (Ph.D. thesis). University of Stellenbosch.

- ^ Broom, R. (1903). "On Some New Primitive Theriodonts". Report of the South African Association for the Advancement of Science. 1: 286–294.

- ^ Broom, R. (1907). "On the geological horizons of the vertebrate genera of the Karroo formation". Records of the Albany Museum. 2: 156–163.

- ^ Broom, R. (1905). "On the use of the term Anomodontia". Records of the Albany Museum. 1 (4): 266–269.

- ^ Broom, R. (1908). "On Some New Therocephalian Reptiles". Annals of the South African Museum. 4 (Pt. 8): 361–367.

- ^ a b c d Huttenlocker, A. (2009). "An investigation into the cladistic relationships and monophyly of therocephalian therapsids (Amniota: Synapsida)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 157 (4): 865–891. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00538.x.

- ^ Kemp, T. S. (1982). Mammal-like reptiles and the origin of mammals. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-404120-2.

- ^ a b c Hopson, J. A.; Barghusen, H (1986). "An analysis of therapsid relationships". In Hotton, N.; MacLean, P. D.; Roth, J. J.; Roth, E. C. (eds.). The ecology and biology of mammal-like reptiles. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 83–106.

- ^ van den Heever, J. A. (1980). "On the validity of the therocephalian family Lycosuchidae (Reptilia, Therapsida)". Annals of the South African Museum. 81: 111–125.

- ^ van den Heever, J. A. (1994). "The Cranial Anatomy of the Early Therocephalia (Amniota: Therapsida)". Annals of the University of Stellenbosch. 1. ISBN 978-0-7972-0498-0.

- ^ Abdala, F.; Kammerer, C. F.; Day, M. O.; Jirah, S.; Rubidge, B. S. (2014). "Adult morphology of the therocephalian Simorhinella baini from the middle Permian of South Africa and the taxonomy, paleobiogeography, and temporal distribution of the Lycosuchidae". Journal of Paleontology. 88 (6): 1139–1153. doi:10.1666/13-186. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 129323281.

- ^ a b Liu, J.; Abdala, F. (2022). "The emblematic South African therocephalian Euchambersia in China: a new link in the dispersal of late Permian vertebrates across Pangea". Biology Letters. 18 (7) 20220222. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2022.0222. PMC 9278400. PMID 35857894.

- ^ Kammerer, C. F.; Masyutin, V. (2018). "A new therocephalian (Gorynychus masyutinae gen. et sp. nov.) from the Permian Kotelnich locality, Kirov Region, Russia". PeerJ. 6. e4933. doi:10.7717/peerj.4933. PMC 5995100. PMID 29900076.

- ^ Liu, J.; Abdala, F. (2019). "The tetrapod fauna of the upper Permian Naobaogou Formation of China: 3. Jiufengia jiai gen. et sp. nov., a large akidnognathid therocephalian". PeerJ. 7. e6463. doi:10.7717/peerj.6463. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6388668. PMID 30809450.

- ^ Abdala, F. (2007). "Redescription of Platycraniellus elegans (Therapsida, Cynodontia) from the Lower Triassic of South Africa, and the Cladistic Relationships of Eutheriodonts". Palaeontology. 50 (3): 591–618. Bibcode:2007Palgy..50..591A. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00646.x. S2CID 83999660.

- ^ Botha, J.; Abdala, F.; Smith, R. M. H. (2007). "The oldest cynodont: new clues on the origin and diversification of the Cynodontia". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 149: 477–492. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00268.x.

- ^ Sidor, C. A.; Kulik, Z. T.; Huttenlocker, A. K. (2022). "A new bauriamorph therocephalian adds a novel component to the Lower Triassic tetrapod assemblage of the Fremouw Formation (Transantarctic Basin) of Antarctica". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (6) e2081510. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.2081510. S2CID 250663346.

- ^ Sigurdsen, T.; Huttenlocker, A. K.; Modesto, S. P.; Rowe, T. B.; Damiani, R. (2012). "Reassessment of the morphology and paleobiology of the therocephalian Tetracynodon darti (Therapsida), and the phylogenetic relationships of Baurioidea". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (5): 1113–1134. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.688693. S2CID 84457790.

- ^ Huttenlocker, A. K. (2014). "Body Size Reductions in Nonmammalian Eutheriodont Therapsids (Synapsida) during the End-Permian Mass Extinction". PLOS ONE. 9 (2). e87553. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...987553H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087553. PMC 3911975. PMID 24498335.

- ^ Liu, J.; Abdala, F. (2023). "Late Permian terrestrial faunal connections invigorated: the first whaitsioid therocephalian from China". Palaeontologia africana. 56: 16–35. hdl:10539/35706.

External links

[edit] Media related to Therocephalia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Therocephalia at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Therocephalia at Wikispecies

Data related to Therocephalia at Wikispecies