Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

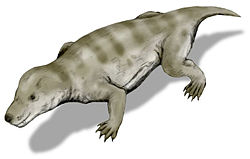

Thrinaxodon

View on Wikipedia

| Thrinaxodon Temporal range: Early Triassic,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil of T. liorhinus in National Museum of Natural History | |

| |

| Diagram of skull in lateral view | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | Cynodontia |

| Clade: | Epicynodontia |

| Family: | †Thrinaxodontidae Watson & Romer, 1956 |

| Genus: | †Thrinaxodon Seeley, 1894 |

| Type species | |

| Thrinaxodon liorhinus Seeley, 1894

| |

Thrinaxodon is an extinct genus of cynodonts which lived in what are now South Africa and Antarctica during the Early Triassic. The genus contains a single species, T. liorhinus.

Similar to other therapsids, Thrinaxodon adopted a semi-sprawling posture, an intermediary form between the sprawling position of basal tetrapods and the more upright posture present in current mammals.[1] Thrinaxodon is prevalent in the fossil record, and one of the specimens represent the oldest known record of burrowing behavior among cynodonts.[2]

Description

[edit]

Thrinaxodon was a small synapsid roughly the size of a fox.[2] Allometric study of its skull suggests that Thrinaxodon was an omnivore.[3] It was capable of and reliant on tympanic hearing similar to hearing of extant mammals, as evidenced by the examination of its mandibular ear bones and soft-tissue eardrum based on finite element analyses.[4]

Skull

[edit]The nasals of Thrinaxodon are pitted with a large number of foramina. The nasals narrow anteriorly and expand anteriorly and articulate directly with the frontals, pre-frontals and lacrimals; however, there is no interaction with the jugals or the orbitals. The maxilla of Thrinaxodon is also heavily pitted with foramina.[5] The arrangement of foramina on the snout of Thrinaxodon resembles that of lizards, such as Tupinambis, and also bears a single large infraorbital foramen.[5][6] As such, Thrinaxodon would have had non-muscular lips like those of lizards, not mobile, muscular ones like those of mammals.[5] Without the infraorbital foramen and its associated facial flexibility, it is unlikely that Thrinaxodon would have had whiskers.[6][7]

On the skull roof of Thrinaxodon, the fronto-nasal suture represents an arrow shape instead of the general transverse process seen in more primitive skull morphologies. The prefrontals, which are slightly anterior and ventral to the frontals exhibit a very small size and come in contact with the post-orbitals, frontals, nasals and lacrimals. More posteriorly on the skull, the parietals lack a sagittal crest. The cranial roof is the narrowest just posterior to the parietal foramen, which is very nearly circular in shape. The temporal crests remain quite discrete throughout the length of the skull. The temporal fenestra have been found with ossified fasciae, giving evidence of some type of a temporal muscle attachment.[5]

The upper jaw contains a secondary palate which separates the nasal passages from the rest of the mouth, which would have given Thrinaxodon the ability to breathe uninterrupted, even if food had been kept in its mouth. This adaptation would have allowed the Thrinaxodon to mash its food to a greater extent, decreasing the amount of time necessary for digestion. The maxillae and palatines meet medially in the upper jaw developing a midline suture. The maxillopalatine suture also includes a posterior palatine foramen. The large palatal roof component of the vomer in Thrinaxodon is just dorsal to the choana, or interior nasal passages. The pterygoid bones extend in the upper jaw and enclose small interpterygoid vacuities that are present on each side of the cultriform processes of the parasphenoids. The parasphenoid and basisphenoid are fused, except for the most anterior/dorsal end of the fused bones, in which there is a slight separation in the trabecular attachment of the basisphenoid.[5]

The otic region is defined by the regions surrounding the temporal fenestrae. Most notable is evidence of a deep recess that is just anterior to the fenestra ovalis, containing evidence of smooth muscle interactions with the skull. Such smooth muscle interactions have been interpreted to be indicative of the tympanum and give the implications that this recess, in conjunction with the fenestra ovalis, outline the origin of the ear in Thrinaxodon. This is a new synapomorphy as this physiology had arisen in Thrinaxodon and had been conserved through late Cynodontia. The stapes contained a heavy cartilage plug, which was fit into the sides of the fenestra ovalis; however, only one half of the articular end of the stapes was able to cover the fenestra ovalis. The remainder of this pit opens to an "un-ossified" region which comes somewhat close to the cochlear recess, giving one the assumption that inner ear articulation occurred directly within this region.[5]

The skull of Thrinaxodon is an important transitional fossil which supports the simplification of synapsid skulls over time. The most notable jump in bone number reduction had occurred between Thrinaxodon and Probainognathus, a change so dramatic that it is most likely that the fossil record for this particular transition is incomplete. Thrinaxodon contains fewer bones in the skull than that of its pelycosaurian ancestors.[8]

Dentition

[edit]Data on the dentition of Thrinaxodon liorhinus was compiled by use of a micro CT scanner on a large sample of Thrinaxodon skulls, ranging between 30 and 96 mm (1.2 and 3.8 in) in length. These dentition patterns are similar to that of Morganucodon, allowing one to make the assumption that these dentition patterns arose within Thrinaxodontidae and extended into the records of early Mammalia. Adult T. liorhinus assumes the dental pattern of the four incisors, one canine and six postcanines on each side of the upper jaw. This pattern is reflected in the lower jaw by a dental formula of three incisors, one canine and seven or eight postcanines on each side of the lower jaw. With this formula, one can make a small note that in general, adult Thrinaxodon contained anywhere between 44 and 46 total teeth.[9]

Upper incisors in T. liorhinus assume a backwards directed cusp, being curved and pointed at their most distal point, and becoming broader and rounder as they reach their proximal insertion point into the premaxilla. The fourth upper incisor is roughly homologous with a small canine tooth in form, but is positioned too far anteriorly to be a functional canine - thus ruling it out as an instance of convergent evolution. Lower incisors possess a very broad base, which is progressively reduced, heading distally towards the tip of the tooth. The lingual face of the lower incisors is most often concave while the labial face is often convex, and these lower incisors are oriented anteriorly, except in some cases for the third lower incisor, which can assume a more dorsoventral orientation. The incisors are, for the most part, single functional teeth encompassing a broad, cone-like morphology. The canines of T. liorhinus possess small dorsoventrally-directed facets on their surfaces, which appear to be involved with occlusion (dentition alignment in upper- and lower jaw closure). Each canine possesses a replacement canine located within the jaw, posterior to the existing canine, neither of the replacement or functional canine teeth possess any serrated margins only the small facets. It is important to note that the lower canine is directed almost vertically (dorsoventrally) while the upper canine is directed slightly anteriorly.[9]

The upper and lower postcanines in T. liorhinus share some common features but also vary quite a fair amount in comparison to one another. The first postcanine (just posterior to the canine) is most often smaller than the other postcanines and is most often bicuspid. Including the first postcanine, if any of the other postcanines are bicuspid, then it is safe to assume that the posterior accessary cusp is present and that that tooth will not have any cingular or labial cusps. If, however, the tooth is tricuspid, then there is a chance of cingular cusps developing, if this occurs then the anterior cusp will be the first to appear and will be the most pronounced cusp. In the upper postcanines, there should be no occurrence of any teeth possessing more than three cusps, and there is no occurrence of any labial cusps on the upper postcanines. The majority of upper postcanines in the juvenile Thrinaxodon are bicuspid, while only one of these upper teeth are tricuspid. The upper postcanines of an intermediate (between juvenile and adult) Thrinaxodon are all tricuspid with no labial or cingular cusps. The adult upper postcanines retain the intermediate physiologies and possess only tricuspid teeth; however, it is possible for cingular cusps to develop in these adult teeth. The ultimate (posterior-most) upper canine is often the smallest of all canines in the entire jaw system. Little data is known of the juvenile and intermediate forms of the lower postcanines in Thrinaxodon, but the adult lower postcanines all possess multiple (any value more than three) cusps as well as the only appearance of labial cusps. Some older specimens have been found that possess no multiple-cups lower canines, possibly a response to old age or teeth replacement.[9]

Thrinaxodon shows one of the first occurrences of replacement teeth in cynodonts. This was discerned by the presence of replacement pits, which are situated lingual to the functional tooth in the incisors and postcanines. While a replacement canine does exist, more often than not it is not erupted and the original functional canine remains.[9]

Histology

[edit]

The bone tissue of Thrinaxodon consists of fibro-lamellar bone, to a varying degree across all the separate limbs, most of which develops into parallel-fibred bone tissue towards the periphery. Each of the bones contains a large abundance of globular osteocyte lacunae which radiate a multitude of branched canaliculi. Ontogenetically early bones - mostly consisting of fibro-lamellar tissue - possessed a large amount of vascular canals. These canals are oriented longitudinally within primary osteons that contain radial anastomoses. Regions consisting mostly of parallel-fibred bone tissue contain few simple vascular canals, in comparison to the nearby fibro-lamellar tissues. Parallel-fibred peripheral bone tissue are indicative that bone growth began to slow, and they bring about the assumption that this change in growth was due to the age of the specimen in question. Combine this with the greater organization of osteocyte lacunae in the periphery of adult T. liorhinus, and we approach the assumption that this creature grew very quickly in order to reach adulthood at an accelerated rate. Before Thrinaxodon, ontogenical patterns such as this had not been seen, establishing the idea that reaching peak size rapidly was an adaptively advantageous trait that had arisen with Thrinaxodon.[10]

Within the femur of Thrinaxodon, there is no major region of the bone that is made of parallel-fibred tissues; however, there is a small ring of parallel-fibred bone within the mid-cortex. The remainder of the femur is made of fibro-lamellar tissue; however, the globular osteocyte lacunae become much more organized and the primary osteons assume less vasculature than many other bones as you begin to approach the subperiosteal surface. The femur contains very few bony trabeculae. The humerus differs from the femur in many regards, one of which being that there is a more extensive network of bony trabeculae in the humerus near the meduallary cavity of the bone. The globular osteocyte lacunae become more flattened as you get closer and closer to the midshaft of the humerus. While the vasculature is present, the humerus contains no secondary osteons. The radii and ulnae of Thrinaxodon represent roughly the same histological patterns. In contrast to the humerii and femora, the parallel-fibred region is far more distinct in the distal bones of the forelimb. The medullary cavities are surrounded by multiple layers of very poorly vascularized endosteal lamellar tissue, along with very large cavities near the medullary cavity of the metaphyses.[10]

Discovery and naming

[edit]

Thrinaxodon was originally discovered in the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of the Beaufort Group of South Africa. The genoholotype, BMNH R 511, was in 1887 described by Richard Owen as the plesiotype of Galesaurus planiceps.[11] In 1894 it was by Harry Govier Seeley made a separate genus with as type species Thrinaxodon liorhinus. Its generic name was taken from the Ancient Greek for "trident tooth", thrinax and odon. The specific name is Latinised Greek for "smooth-nosed".

Thrinaxodon was initially believed to be isolated to that region. Other fossils in South Africa were recovered from the Normandien and Katberg Formations.[12] It had not been until 1977 that additional fossils of Thrinaxodon had been discovered in the Fremouw Formation of Antarctica. Upon its discovery there, numerous experiments were done to confirm whether or not they had found a new species of Thrinaxodontidae, or if they had found another area which T. liorhinus called home. The first experiment was to evaluate the average number of pre-sacral vertebrae in the Antarctic vs African Thrinaxodon. The data actually showed a slight difference between the two, in that the African T. liorhinus contained 26 presacrals, while the Antarctic Thrinaxodon had 27 pre-sacrals. In comparison to other cynodonts, 27 pre-sacrals appeared to be the norm throughout this sub-section of the fossil record. The next step was to evaluate the size of the skull in the two different discovery groups, and in this study they found no difference between the two, the first indication that they may in fact be of the same species. The ribs were the final physiology to be cross-examined, and while they portrayed slight differences in the expanded ribs, against one another, the most important synapomorphy remained consistent between the two, and that was that the intercostal plates overlapped with one another. These evaluations led to the conclusion that they had not found a new species of Thrinaxodontidae, but yet they had found that Thrinaxodon occupied two different geographical regions, which today are separated by an immense expanse of ocean. This discovery was one of many to support the idea of a connected land mass, and that during the early Triassic, Africa and Antarctica must have been linked in some way, shape or form.[13]

Classification

[edit]

Thrinaxodon belongs to the clade Epicynodontia, a subdivision of the greater clade Cynodontia. Its closest relative based on phylogenetic analyses is Platycraniellus.[14]

Paleobiology

[edit]Ontogeny

[edit]There appear to be nine cranial features that successfully separate Thrinaxodon into four ontogenetic stages. The paper denotes that in general, the Thrinaxodon skull increased in size isometrically, except for four regions, one of which being the optic region. Much of the data assumes that the length of the sagittal crest increased at a greater rate in relation to the rest of the skull. The posterior sagittal crest to appear in an earlier ontogenetic stage than the more anterior crest had, and in conjunction with the dorsal deposition of bone, a unified sagittal crest had developed rather than having a single suture span the entire length of the skull.[3]

The bone histology of Thrinaxodon indicates that it most likely had very rapid bone growth during juvenile development, and much slower development throughout adulthood, giving rise to the idea that Thrinaxodon reached peak size very early in its life.[10]

There is strong evidence that juvenile Thrinaxodon were cared for by their parents, as evidenced by fossilised aggregations of adults with multiple juvenile individuals of a similar size, likely indicating these juveniles were the same age and belonged to the same clutch.[15]

Posture

[edit]The posture of Thrinaxodon is an interesting subject, because it represents a transition between the sprawling behavior of the more lizard-like pelycosaurs and the more upright behavior found in modern, and many extinct, Mammalia. In cynodonts such as Thrinaxodon, the distal femoral condyle articulates with the acetabulum in a way that permits the hindlimb to present itself at a 45-degree angle to the rest of the system. This is a large difference in comparison to the distal femoral condyle of pelycosaurs, which permits the femur to be parallel with the ground, forcing them to assume a sprawling-like posture.[1] More interesting is that there is an adaptation that has only been observed within Thrinaxodontidae, which allows them to assume upright posture, similar to that of early Mammalia, within their burrows.[2] These changes in posture are supported by the physiological changes in the torso of Thrinaxodon. Such changes as the first appearance of a segmented rib compartment, in which Thrinaxodon expresses both thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. The thoracic segment of the vertebrae contain ribs with large intercostal plates that most likely assisted with either protection or supporting the main frame of the back. This newly developed arrangement allowed for the appropriate space for a diaphragm, however, without proper soft tissue records, the presence of a diaphragm is purely speculative.[16]

Burrowing

[edit]

Thrinaxodon has been identified as a burrowing cynodont by numerous discoveries in preserved burrow hollows. There is evidence that the burrows are in fact built by the Thrinaxodon to live in them, and they do not simply inhabit leftover burrows by other creatures. Due to the evolution of a segmented vertebral column into thoracic, lumbar and sacral vertebrae, Thrinaxodon was able to achieve flexibilities that permitted it to comfortably rest within smaller burrows, which may have led to habits such as aestivation or torpor. This evolution of a segmented rib cage suggests that this may have been the first instance of a diaphragm in the synapsid fossil record; however, without the proper soft tissue impressions this is nothing more than an assumption.[16][2]

The earliest discovery of a burrowing Thrinaxodon places the specimen found around 251 million years ago, a time frame surrounding the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Much of these fossils had been found in the flood plains of South Africa, in the Karoo Basin. This behavior had been seen at a relatively low occurrence in the pre-Cenozoic, dominated by therapsids, early-Triassic cynodonts and some early Mammalia. Thrinaxodon was in fact the first burrowing cynodont that has been found, showing similar behavioral patterns to that of Trirachodon. The first burrowing vertebrate on record was the dicynodont synapsid Diictodon, and it is possible that these burrowing patterns had passed on to the future cynodonts due to the adaptive advantage of burrowing during the extinction. The burrow of Thrinaxodon consists of two laterally sloping halves, a pattern that has only been observed in burrowing non-mammalian Cynodontia. The changes in vertebral/rib anatomy that arose in Thrinaxodon permit the animals to a greater range of flexibility, and the ability to place their snout underneath their hindlimbs, an adaptive response to small living quarters, in order to preserve warmth and/or for aestivation purposes.[2]

A Thrinaxodon burrow contained an injured temnospondyl, Broomistega. The burrow was scanned using a synchrotron, a tool used to observe the contents of the burrows in this experiment, and not damage the intact specimens. The synchrotron revealed an injured rhinesuchid, Broomistega putterilli, showing signs of broken or damaged limbs and two skull perforations, most likely inflicted by the canines of another carnivore. The distance between the perforations was measured in relation to the distance between the canines of the Thrinaxodon in question, and no such relation was found. Therefore, we may assume that the temnospondyl found refuge in the burrow after a traumatic experience and the T. liorhinus allowed it to stay in its burrow until they both ultimately met their respective deaths. Interspecific shelter sharing is a rare anomaly within the fossil record; this T. liorhinus shows one of the first occurrences of this type of behavior in the fossil record, but it currently is unknown if the temnospondyl inhabited the burrow before or after the death of the nesting Thrinaxodon.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Blob R. 2001. Evolution of hindlimb posture in non-mammalian therapsids: biomechanical tests of paleontological hypotheses. 27(1): 14-38.

- ^ a b c d e Damiani, R.; Modesto, S.; Yates, A.; Neveling, J. (2003). "Earliest evidence of cynodont burrowing". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 270 (1525): 1747–1751. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2427. JSTOR 3592240. PMC 1691433. PMID 12965004.

- ^ a b Jasinoski, S. Abdala F. Fernandez V. (2015). "Ontogeny of the Early Triassic Cynodont Thrinaxodon liorhinus (Therapsida): Cranial Morphology". The Anatomical Record. 298 (8): 1440–1464. doi:10.1002/ar.23116. PMID 25620050. S2CID 205412362.

- ^ Wilken, A. T.; Snipes, C. C. G.; Ross, C. F.; Luo, Z.-X. (2025). "Biomechanics of the mandibular middle ear of the cynodont Thrinaxodon and the evolution of mammal hearing". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 122 (51) e2516082122. doi:10.1073/pnas.2516082122.

- ^ a b c d e f Estes R. 1961. Cranial anatomy of the cynodont Thrinaxodon liorhinus. Museum of comparative Zoology, Harvard University, 125: 165-180.

- ^ a b Benoit, J.; Manger, P. R.; Rubidge, B. S. (2016-05-09). "Palaeoneurological clues to the evolution of defining mammalian soft tissue traits". Scientific Reports. 6 (1) 25604. Bibcode:2016NatSR...625604B. doi:10.1038/srep25604. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4860582. PMID 27157809.

- ^ Benoit, Julien; Ruf, Irina; Miyamae, Juri A.; Fernandez, Vincent; Rodrigues, Pablo Gusmão; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2020). "The Evolution of the Maxillary Canal in Probainognathia (Cynodontia, Synapsida): Reassessment of the Homology of the Infraorbital Foramen in Mammalian Ancestors". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 27 (3): 329–348. doi:10.1007/s10914-019-09467-8. eISSN 1573-7055. ISSN 1064-7554. S2CID 156055693.

- ^ Sidor, C (2001). "Simplification as a trend in synapsid cranial evolution". Evolution. 55 (7): 1419–1442. Bibcode:2001Evolu..55.1419S. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00663.x. PMID 11525465. S2CID 20339164.

- ^ a b c d Abdala, F. Jasinoski S. Fernandez V. (2013). "Ontogeny of the Early Cynodont Thrinaxodon liorhinus (Therapsida): Dental Morphology and Replacement". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (6): 1408–1431. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.775140. S2CID 84620008.

- ^ a b c Botha J. Chinsamy A. 2005. Growth patterns of Thrinaxodon liorhinus, a non-mammalian cynodont from the lower Triassic of South Africa. Paleontology. 48(2): 385-394.

- ^ Richard Owen (February 1887). "On the Skull and Dentition of a Triassic Saurian (Galesaurus planiceps, Ow.)". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 43 (1–4): 1–6. Bibcode:1887QJGS...43....1O. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1887.043.01-04.03.

- ^ "Thrinaxodon liorhinus". PBDB. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ Colbert, Edwin; Kitching, James (1977). "Triassic Cynodont Reptiles from Antarctica". American Museum Novitates (2611): 1–30. hdl:2246/2011.

- ^ Sidor, Christian A.; Smith, Roger M. H. (2004). "A new galesaurid (Therapsida: Cynodontia) from the Lower Triassic of South Africa". Palaeontology. 47 (3): 535–556. Bibcode:2004Palgy..47..535S. doi:10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00378.x. S2CID 129906726.

- ^ Jasinoski, Sandra C.; Abdala, Fernando (10 January 2017). "Aggregations and parental care in the Early Triassic basal cynodonts Galesaurus planiceps and Thrinaxodon liorhinus". PeerJ. 5 e2875. doi:10.7717/peerj.2875. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5228509. PMID 28097072.

- ^ a b Brink A. Note on a new skeleton of Thrinaxodon liorhinus. Abstract. 15-22.

- ^ Fernandez, V.; Abdala, F.; Carlson, K. J.; Cook, D. C.; Rubidge, B. S.; Yates, A.; Tafforeau, P. (2013). Butler, Richard J (ed.). "Synchrotron Reveals Early Triassic Odd Couple: Injured Amphibian and Aestivating Therapsid Share Burrow". PLOS ONE. 8 (6) e64978. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864978F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064978. PMC 3689844. PMID 23805181.

- ^ Fernandez, V.; et al. (2013). "Synchrotron Reveals Early Triassic Odd Couple: Injured Amphibian and Aestivating Therapsid Share Burrow". PLOS ONE. 8 (6) e64978. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864978F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064978. PMC 3689844. PMID 23805181.

Further reading

[edit]- Tim Haines; Paul Chambers (2006). The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Firefly Books Ltd., Canada. 69.

- David Lambert (2003). Dinosaur Encyclopedia. DK Publishing, New York. 202–203.