Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

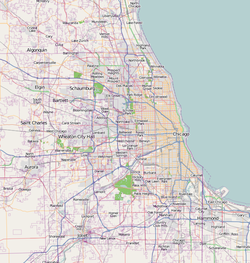

Field Museum of Natural History

View on Wikipedia

The Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH; commonly known as Field Museum) is a natural history museum in Chicago, Illinois, and is one of the largest such museums in the world.[4] The museum is popular for the size and quality of its educational and scientific programs,[5][6] and its extensive scientific specimen and artifact collections.[7] The permanent exhibitions,[8] which attract up to 2 million visitors annually, include fossils, current cultures from around the world, and interactive programming demonstrating today's urgent conservation needs.[9][10] The museum is named in honor of its first major benefactor, Marshall Field, the department-store magnate. The museum and its collections originated from the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition and the artifacts displayed at the fair.[11][12]

Key Information

The museum maintains a temporary exhibition program of traveling shows as well as in-house produced topical exhibitions.[13] The professional staff maintains collections of over 24 million specimens and objects that provide the basis for the museum's scientific-research programs.[4][7][14] These collections include the full range of existing biodiversity, gems, meteorites, fossils, and extensive anthropological collections and cultural artifacts from around the globe.[7][15][16][17] The museum's library, which contains over 275,000 books, journals, and photo archives focused on biological systematics, evolutionary biology, geology, archaeology, ethnology and material culture, supports the museum's academic-research faculty and exhibit development.[18] The academic faculty and scientific staff engage in field expeditions, in biodiversity and cultural research on every continent, in local and foreign student training, and in stewardship of the rich specimen and artifact collections. They work in close collaboration with public programming exhibitions and education initiatives.[14][19][20][21]

History

[edit]

In 1869, and before its formal establishment, the museum acquired the largest collection of birds and bird descriptions, from artist and ornithologist Daniel Giraud Elliot. In 1894, Elliot would become the curator of the Department of Zoology at the museum, where he worked until 1906.[22][23]

To house the exhibits and collections assembled for the World's Columbian Exposition for future generations, Edward Ayer convinced the merchant Marshall Field to fund the establishment of a museum.[11][12][24] Originally titled the Columbian Museum of Chicago in honor of its origins, the Field Museum was incorporated by the State of Illinois on September 16, 1893, for the purpose of the "accumulation and dissemination of knowledge, and the preservation and exhibition of artifacts illustrating art, archaeology, science and history".[25] The Columbian Museum of Chicago occupied the only building remaining from the World's Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park, the Palace of Fine Arts. It is now home to the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry.[10]

In 1905, the museum's name was changed to Field Museum of Natural History to honor its first major benefactor and to reflect its focus on the natural sciences.[26]

Stanley Field was the president in 1906.[27]

During the period from 1943 to 1966,[28][29][30] the museum was known as the Chicago Natural History Museum. In 1921, the Museum moved from its original location in Jackson Park to its present site on Chicago Park District property near downtown Chicago.[31] By the late 1930s the Field Museum had emerged as one of the three premier museums in the United States, the other two being the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.[5]

The museum has maintained its reputation through continuous growth, expanding the scope of collections and its scientific research output, in addition to its award-winning exhibitions, outreach publications, and programs.[6][14][19][32] The Field Museum is part of Chicago's lakefront Museum Campus that includes the John G. Shedd Aquarium and the Adler Planetarium.[9]

In 2015, it was reported that an employee had defrauded the museum of $900,000 over a seven-year period to 2014.[33]

Attendance

[edit]The Museum received 1,018,002 visitors in 2022, ranking the 21st most-visited museum in the United States.[34]

Permanent exhibitions

[edit]Animal Halls

[edit]Animal exhibitions and dioramas such as Nature Walk, Mammals of Asia, and Mammals of Africa allow visitors an up-close look at the diverse habitats that animals inhabit. Most notably featured are the man-eating lions of Tsavo.[35] The Mfuwe man eating lion is also on display.

| Species represented in the Animal Halls | Gallery |

|---|---|

| Aardvark | Mammals of Africa |

| African Buffalo | Mammals of Africa |

| African Elephant | Stanley Field Hall |

| Alaskan Brown Bear | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Argali | Mammals of Asia |

| Barasingha | Mammals of Asia |

| Beaver | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Beisa Oryx | Mammals of Africa |

| Bengal Tiger | Mammals of Asia |

| Blackbuck Antelope | Mammals of Asia |

| Black Rhinoceros | Mammals of Africa |

| Black Wildebeest | Mammals of Africa |

| Bongo | Mammals of Africa |

| Burchell's Zebra | Mammals of Africa |

| Capybara | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Caribou | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Caribbean Manatee | Sea Mammals |

| Cattle Egret | Mammals of Asia |

| Cheetah | Mammals of Africa |

| Chital | Mammals of Asia |

| Common Eland | Mammals of Africa |

| Cougar | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Dibatag | Mammals of Africa |

| Lion | Mammals of Africa |

| Elephant Seal | Sea Mammals |

| Gaur | Mammals of Asia |

| Gelada Baboon | Mammals of Africa |

| Gerenuk | Mammals of Africa |

| Giant Anteater | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Giant Forest Hog | Mammals of Africa |

| Giant Panda | Mammals of Asia |

| Giant Sable Antelope | Mammals of Africa |

| Glacier Bear | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Grant's Gazelle | Mammals of Africa |

| Greater Kudu | Mammals of Africa |

| Guanocos | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Hog Deer | Mammals of Asia |

| Hyacinth Macaws | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Ibex | Mammals of Asia |

| Imperial Woodpecker | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Indian Gazelle | Mammals of Asia |

| Indian Rhinoceros | Mammals of Asia |

| Indian Sambar | Mammals of Asia |

| Jaguar | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Leopard | Mammals of Asia |

| Lesser Kudu | Mammals of Africa |

| Mantled Guereza | Mammals of Africa |

| Malay Tapir | Mammals of Asia |

| Marsh Deer | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Mexican Grizzly Bear | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Mountain Nyala | Mammals of Africa |

| Mule Deer | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Muskoxen | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Narwhal | Sea Mammals |

| Nilgai | Mammals of Asia |

| Northern Fur Seal | Sea Mammals |

| Orangutan | Mammals of Asia |

| Plains Zebra | Mammals of Africa |

| Polar Bear | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Proboscis Monkey | Mammals of Asia |

| Pronghorn | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Reticulated Giraffe | Mammals of Africa |

| Roosevelt Elk | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Sea Otter | Sea Mammals |

| Sloth Bear | Mammals of Asia |

| Snow Leopard | Mammals of Asia |

| Somali Wildass | Mammals of Africa |

| Spotted Hyena | Mammals of Africa |

| Striped Hyena | Mammals of Asia |

| Swayne's Hartebeest | Mammals of Africa |

| Takin | Mammals of Asia |

| Tapir | Messages from the Wilderness |

| Thomas' Uganda Kob | Mammals of Africa |

| Walrus | Sea Mammals |

| Wart Hog | Mammals of Africa |

| Water Buffalo | Mammals of Asia |

| Weddell Seal | Sea Mammals |

| White Rhinoceros | Mammals of Africa |

| Yellow-checked Gibbon | Mammals of Asia |

Evolving Planet

[edit]Evolving Planet follows the evolution of life on Earth over 4 billion years. The exhibit showcases fossils of single-celled organisms, ancient Invertebrates, early fish, Permian synapsids, dinosaurs, extinct mammals, and early hominids.[36] The Field Museum's non-mammalian synapsid collection consists of over 1100 catalogued specimens, including 46 holotypes. The collection of basal synapsids includes 29 holotypes of caseid, ophiacodontid, edaphosaurid, varanopid, and sphenacodontid species – approximately 88% of catalogued specimens.[37]

Inside Ancient Egypt

[edit]Inside Ancient Egypt offers a glimpse into what life was like for ancient Egyptians. Twenty-three human mummies are on display as well as many mummified animals. The exhibit features a three-story replica (featuring two authentic rooms with 5,000-year-old hieroglyphs) of the mastaba tomb of Unas-Ankh, the son of Unas (the last pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty). Also displayed are an ancient marketplace showing artifacts of everyday life, a shrine to the cat goddess Bastet, and dioramas showing the afterlife preparation process for the dead.[38]

In 2024 the museum performed CT scans on 26 of their mummies.[39]

The Ancient Americas

[edit]

The Ancient Americas displays 13,000 years of human ingenuity and achievement in the Western Hemisphere, where hundreds of diverse societies thrived long before the arrival of Europeans. In this large permanent exhibition visitors can learn the epic story of the peopling of these continents, from the Arctic to the tip of South America.[40] The exhibit consists of six displays: Ice Age Hunters, Innovative Hunters and Gatherers, Farming Villagers, Powerful Leaders, Rulers and Citizens, and Empire Builders. Visitors are encouraged to begin with Ice Age Hunters and conclude with Empire Builders.[41] In this way, visitors can understand the cultural and economic progression of the Ancient Americas. Throughout the exhibit, collections are displayed in a way that emphasizes the cultural context of the artifacts.

The six displays draw from the Field Museum's massive North America collection. Significant collections utilized by the exhibit include pre-Columbian artifacts gathered by Mayanists Edward H. Thompson and John E. S. Thompson.[42] Additionally, former curator Paul Sidney Martin's American Southwest collection makes up a significant portion of the "Farming Villagers" display.[43] The Empire Builders display includes Aztec and Incan artifacts gathered in the 19th century.[44]

The Ancient Americas exhibit transitions to the Alsdorf Hall of Northwest Coast and Arctic Peoples and eventually the Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories exhibit. This emphasizes the thematic unity of the Field Museum's American collections.[45]

Cultural Halls

[edit]Cultural exhibitions include sections on Tibet and China, where visitors can view traditional clothing.[46] There is also an exhibit on life in Africa, where visitors can learn about the many different cultures on the continent,[47] and an exhibit where visitors may "visit" several Pacific Islands.[48] The museum houses an authentic 19th-century Māori Meeting House, Ruatepupuke II,[49] from Tokomaru Bay, New Zealand. Additionally, the Field Museum's Northwest Coast Collections showcase the early work of Franz Boas and Frederic Ward Putnam's work with the Kwakwakaʼwakw (Kwakiutl) people in the Alsdorf Hall of Northwest Coast and Arctic Peoples.[50] Finally, the Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories permanent exhibition displays the Field Museum's current collaborative efforts with the indigenous people of North America.[51]

Africa

[edit]The Africa cultural hall opened at the Field Museum in November 1993. It offers 14 different displays that are primarily ethnographic in nature. Several African countries are exhibited as well as a variety of geographical areas including the Sahara and East African rift valley. The final section is dedicated to the African diaspora with a particular focus on the impact of the slave trade on the continent.[52] The Africa permanent exhibit owes most of its collection to the efforts of Wilfred D. Hambly.[53]

Peoples of the Arctic and Pacific Northwest

[edit]

This extensive permanent exhibition covers two culture areas that were vitally important to the early work of the Field Museum—the Arctic and Pacific Northwest. The Pacific Northwest collection is more extensive, but both collections are organized into four categories: subsistence, village and society, the spiritual world, and art. Major displays include a variety of dioramas and a large collection of totem poles.[50] The current permanent exhibition has its origins in the Maritime Peoples hall created by the Field Museum's curator of North American archaeology and ethnology James VanStone.[54]

Cyrus Tang Hall of China

[edit]

The Cyrus Tang Hall of China opened as a permanent exhibition in 2015. The hall consists of five sections: Diverse Landscapes, Ritual and Power, Shifting Power, Beliefs and Practices, and Crossing Boundaries. The first three sections are organized chronologically while the final two sections are organized by theme. Three hundred and fifty objects are displayed throughout the five galleries.[46] These artifacts are a sample chosen from the Field Museum's significant China collection. This collection was gathered by the sinologist Berthold Laufer.[55]

Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories

[edit]Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories opened as a permanent exhibition in 2021. This exhibit is an extensive renovation of the former Native American Hall at the Field Museum. Native Truths utilizes about 400 artifacts to interpret Native American culture and history while also addressing modern-day challenges.[51] The exhibition is a result of a changing attitude towards Native Americans that emphasized Native peoples instead of Native artifacts.[56]

Regenstein Halls of the Pacific

[edit]

This exhibit is dedicated to the natural and cultural history of the Pacific Islands and is organized into five different sections: the natural history of the islands, the cultural origins of Pacific Islanders, a canoe display, an ethnographic collection showcasing New Guinea's Huon Gulf, and a modern Tahitian market. The final portion of the exhibit is dedicated to the ceremonial arts of the Pacific peoples.[57] The majority of the collection was gathered by curator Albert Buell Lewis.[58] Building upon Lewis' desire to portray cultures as living and participative, the exhibit was intentionally designed to demonstrate how the Pacific Islands interact with the contemporary world.[59]

Geology Halls

[edit]The Grainger Hall of Gems consists of a large collection of diamonds and gems from around the world, and also includes a Louis Comfort Tiffany stained glass window.[60] The Hall of Jades focuses on Chinese jade artifacts spanning 8,000 years.[61] The Robert A. Pritzker Center for Meteoritics and Polar Studies contains a large collection of fossil meteorites.[62][63]

Underground Adventure

[edit]The Underground Adventure gives visitors a bug's-eye look at the world beneath their feet. Visitors can see what insects and soil look like from that size, while learning about the biodiversity of soil and the importance of healthy soil.[64]

Working Laboratories

[edit]- DNA Discovery Center – Visitors can watch real scientists extract DNA from a variety of organisms. Museum goers can also speak to a live scientist through the glass every day and ask them any questions about DNA.

- McDonald's Fossil Prep Lab – The public can watch as paleontologists prepare real fossils for study.

- The Regenstein Pacific Conservation Laboratory – 1,600-square-foot (150 m2) conservation and collections facility. Visitors can watch as conservators work to preserve and study anthropological specimens from all over the world.

Sue, the Tyrannosaurus rex

[edit]

On May 17, 2000, the Field Museum unveiled Sue, the largest T. rex specimen discovered at the time. Sue has a length of 40.5 feet (12.3 m), stands 13 feet (4.0 m) tall at the hips, and has been estimated at 8.4–14 metric tons (9.26–15.4 short tons) as of 2018.[65][66] The specimen is estimated to be 67 million years old. The fossil was named after the person who discovered it, Sue Hendrickson, and is commonly referred to as female, although the dinosaur's actual sex is unknown.[67] The original skull is not mounted to the body due to the difficulties in examining the specimen 13 feet off the ground, and for nominal aesthetic reasons (the replica does not require a steel support under the mandible). An examination of the bones revealed that Sue died at age 28, a record for the fossilized remains of a T. rex until Trix was found in 2013. In December 2018 after revisions of the skeletal assembly were made to reflect new concepts of Sue's structure,[68] display of the skeleton was moved into a new suite in The Griffin Halls of Evolving Planet.[69]

Scientific collections

[edit]Professionally managed and maintained specimen and artifact collections, such as those at the Field Museum of Natural History, are a major research resource for the national and international scientific community, supporting extensive research that tracks environmental changes, benefits homeland security, public health and safety, and serves taxonomy and systematics research.[70] Many of Field Museum's collections rank among the top ten collections in the world, e.g., the bird skin collection ranks fourth worldwide;[71][72] the mollusk collection is among the five largest in North America;[73] the fish collection is ranked among the largest in the world.[74] The scientific collections of the Field Museum originate from the specimens and artifacts assembled between 1891 and 1893 for the World Columbian Exposition.[14][25][75][76][77] Already at its founding, the Field Museum had a large anthropological collection.[78]

A large number of the early natural history specimens were purchased from Ward's Natural History Establishment[79] in Rochester, New York. An extensive acquisition program, including large expeditions conducted by the museum's curatorial staff resulted in substantial collection growth.[10][14][80] During the first 50 years of the museum's existence, over 440 Field Museum expeditions acquired specimens from all parts of the world.[81]

In addition, material was added through purchase, such as H. N. Patterson's herbarium in 1900,[82] and the Strecker butterfly collection in 1908.[83]

Extensive specimen material and artifacts were given to the museum by collectors and donors, such as the Boone collection of over 3,500 East Asian artifacts, consisting of books, prints and various objects. In addition, "orphaned collections" were and are taken in from other institutions such as universities that change their academic programs away from collections-based research. For example, already beginning in 1907, Field Museum accepted substantial botanical specimen collections from universities such as University of Chicago, Northwestern University and University of Illinois at Chicago, into its herbarium. These specimens are maintained and continuously available for researchers worldwide.[14] The Index Herbariorum code assigned to this botanic garden is F[84] and it is used when citing housed specimens. Targeted collecting in the US and abroad for research programs of the curatorial and collection staff continuously add high quality specimen material and artifacts; e.g., Dr. Robert Inger's collection of frogs from Borneo as part of his research into the ecology and biodiversity of the Indonesian fauna.[16][85][86]

Collecting of specimens and acquisition of artifacts is nowadays subject to clearly spelled-out policies and standards, with the goal to acquire only materials and specimens for which the provenance can be established unambiguously. All collecting of biological specimens is subject to proper collecting and export permits; frequently, specimens are returned to their country of origin after study. Field Museum stands among the leading institutions developing such ethics standards and policies; Field Museum was an early adopter of voluntary repatriation practices of ethnological and archaeological artifacts.[10][78]

Collection care and management

[edit]Field Museum collections are professionally managed[87] by collection managers and conservators, who are skilled in preparation and preservation techniques. Numerous maintenance and collection management tools were and are being advanced at Field Museum. For example, Carl Akeley's development of taxidermy excellence produced the first natural-looking mammal and bird specimens for exhibition as well as for study.[88] Field Museum curators developed standards and best practices for the care of collections.[89] Conservators at the Field Museum have made notable contributions to conservation science with methods of preservation of artifacts including the use of pheromone trapping for control of webbing clothes moths.[90]

The Field Museum was an early adopter of positive-pressure based approaches to control of environment in display cases,[91] using control modules for humidity control in several galleries where room-level humidification was not practical.[92][93] The museum has also adopted a low-energy approach to maintain low humidity to prevent corrosion in archaeological metals using ultra-well-sealed barrier film micro-environments.[94] Other notable contributions include methods for dyeing Japanese papers to color match restorations in organic substrates,[95] the removal of display mounts from historic objects,[96] testing of collections for residual heavy metal pesticides,[97][98] presence of early plastics in collections,[99] the effect of sulfurous products in display cases,[100] and the use of light tubes in display cases.[101]

Concordant with research developments, new collection types, such as frozen tissue collections, requiring new collecting and preservation techniques are added to the existing holdings.[102][103]

Despite the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act in 1990, the Field Museum is estimated to hold more than 1000 Native American remains that have not been repatriated.[104]

Collection records

[edit]

Collection management requires meticulous record keeping. Handwritten ledgers captured specimen and artifact data in the past. Field Museum was an early adopter of computerization of collection data beginning in the late 1970s.[14][105] Field Museum contributes its digitized collection data to a variety of online groups and platforms, such as: HerpNet, VertNet and Antweb,[106] Global Biodiversity Information Facility (also known as GBif),[107] and others. All Field Museum collection databases are unified and currently maintained in KE EMu software system. The research value of digitized specimen data and georeferenced locality data is widely acknowledged,[108] enabling analyses of distribution shifts due to climate changes, land use changes and others.[109]

Collection use

[edit]During the World's Columbian Exposition, all acquired specimens and objects were on display;[75] the purpose of the World's Fair was exhibition of these materials. For example, just after opening of the Columbian Museum of Chicago, the mollusk collection occupied one entire exhibit hall, displaying 3,000 species of mollusks on about 1,260 square feet (117 m2). By 1910, 20,000 shell specimens were on display, with an additional 15,000 "in storage".[110]

Only a small fraction of the specimens and artifacts are publicly displayed. The vast majority of specimens and artifacts are used by a wide range of people in the museum and around the world. Field Museum curatorial faculty and their graduate students and postdoctoral trainees use the collections in their research and in training e.g., in formal high school and undergraduate training programs. Researchers from all over the world can search online for particular specimens and request to borrow them, which are shipped routinely under defined and published loan policies, to ensure that the specimens remain in good condition.[111] For example, in 2012, Field Museum's Zoology collection processed 419 specimen loans, shipping over 42,000 specimens to researchers, per its Annual Report.[112]

The collection specimens are an important cornerstone of research infrastructure in that each specimen can be re-examined and with the advancement of analytic techniques, new data can be gleaned from specimens that may have been collected more than 150 years ago.[113]

Library

[edit]The library at the Field Museum was organized in 1893 for the museum's scientific staff, visiting researchers, students, and members of the general public as a resource for research, exhibition development and educational programs. The 275,000 volumes of the Main Research Collections concentrate on biological systematics, environmental and evolutionary biology, anthropology, botany, geology, archaeology, museology and related subjects.[114] The Field Museum Library includes the following collections:

Ayer collection

[edit]This private collection of Edward E. Ayer, the first president of the museum, contains virtually all the important works in the history of ornithology and is especially rich in color-illustrated works.[115]

Laufer Collection

[edit]The working collection of Dr. Berthold Laufer, America's first sinologist and Curator of Anthropology until his death in 1934, consists of about 7,000 volumes in Chinese, Japanese, Tibetan, and numerous Western languages on anthropology, archaeology, religion, science, and travel.[116]

Photo archives

[edit]The photo archives contain over 250,000 images in the areas of anthropology, botany, geology and zoology and documents the history and architecture of the museum, its exhibitions, staff and scientific expeditions. In 2008 two collections from the Photo Archives became available via the Illinois Digital Archives (IDA): The World's Columbian Exposition of 1893[117] and Urban Landscapes of Illinois.[118] In April 2009, the Photo Archives became part of Flickr Commons.[119]

Karl P. Schmidt Memorial Herpetological Library

[edit]The Karl P. Schmidt Memorial Herpetological Library, named for Karl Patterson Schmidt is a research library containing over 2,000 herpetological books and an extensive reprint collection.[120]

John James Audubon's Birds of North America

[edit]The Field Museum's Double Elephant folio of Audubon's The Birds of America is one of only two known copies that were arranged in taxonomic order. Additionally, it contains all 13 composite plates. The Field's copy belonged to Audubon's family physician Dr. Benjamin Phillips.[121]

Education and research

[edit]The Field Museum offers opportunities for informal and more structured public learning. Exhibitions remain the primary means of informal education, but throughout its history the Museum has supplemented this approach with innovative educational programs. The Harris Loan Program, for example, begun in 1912, reaches out to children in Chicago area schools, offering artifacts, specimens, audiovisual materials, and activity kits.[122] The Department of Education, begun in 1922, offers classes, lectures, field trips, museum overnights and special events for families, adults and children.[123] The Field has adopted production of the YouTube channel The Brain Scoop, hiring its host Emily Graslie full-time as 'Chief Curiosity Correspondent'.[124]

The Museum's curatorial and scientific staff in the departments of Anthropology,[125] Botany,[126] Geology,[127] and Zoology[128] conducts basic research in systematic biology and anthropology, besides its responsibility for collections management, and educational programs. It has long maintained close links, including joint teaching, students, seminars, with the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago.[129] Professional symposia and lectures, like the annual A. Watson Armour III Spring Symposium, present scientific results to the international scientific community and the public at large.[citation needed]

Academic publication

[edit]The museum used to publish four peer-reviewed monograph series issued under the collective title Fieldiana, devoted to anthropology, botany, geology and zoology.[130]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Museum History". The Field Museum. February 23, 2011.

- ^ "Theme Index and Museum Index 2022: The Global Attractions Attendance Report". Themed Entertainment Association. February 1, 2022. p. 75. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ a b Bardoe, Cheryl (2011). The Field Museum. Beckon Books.

- ^ a b Coleman, L. V. (1939). The Museums in America: A critical study. Vol. 1–3. The American Association of Museums.

- ^ a b Williams, P. M. (1973). Museums of Natural History and the people who work in them. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- ^ a b c Boyer, B. H. (1993). The Natural History of the Field Museum: Exploring the Earth and its People. Chicago, Illinois: Field Museum.

- ^ Metzler, S. (2007). Theatres of Nature Dioramas at the Field Museum. Chicago, Illinois: Field Museum of Natural History.

- ^ a b "Museums In the Park". museumsinthepark.org.

- ^ a b c d Alexander, E. P. (1979). Museums in Motion: An Introduction to the History and Functions of Museums. Nashville, Tennessee: American Association for State and Local History.

- ^ a b "Field Museum". Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "About the Field Museum". fieldmuseum.org. Field Museum. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ "Field Museum Traveling Exhibitions". April 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nitecki, M. (1980). "Field Museum of Natural History". ASC Newsletter. 8 (5): 61–70.

- ^ Shopland, J. M.; Breslauer, L. (1998). The Anthropology Collections of the Field Museum. Chicago, Illinois: The Field Museum.

- ^ a b Resetar, A.; Voris, H. K. (1997). Herpetology at the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago: the First Hundred Years. Lawrence, Kansas: American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists.

- ^ Lowther, P. (1995). Ornithology at the Field Museum, pp. 145–161. In: Davis, W. E. Jr. and J. A. Jackson (eds). Contributions to the History of North American Ornithology. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, 12, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- ^ Williams, Benjamin W.; Fawcett, W. Peyton (1985). "Field Museum of Natural History Library". Science & Technology Libraries. 6 (1/2): 27–34. doi:10.1300/J122v06n01_04.

- ^ a b Nash, S. E.; Feinman, G. M. (2003). Curators, collections, and contexts: Anthropology at the Field Museum, 1893–2002. Chicago, Illinois: Field Museum of Natural History.

- ^ "Faculty and Trainers | Committee on Evolutionary Biology". evbio.uchicago.edu.

- ^ "University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Anthropology, Associated Field Museum Faculty". Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "American Museum of Natural History Research Library: Elliot, Daniel Giraud 1835-1915 (amnhp_1000637)". data.library.amnh.org. February 22, 1999. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ^ "Daniel Giraud Elliot (January, 1917)" (PDF). The Auk. Retrieved December 27, 2023 – via sora.unm.edu.

- ^ Lockwood, F. C. (1929). The life of Edward E. Ayer. Chicago, Illinois: A. C. McClurg.

- ^ a b Farrington, O. C. (1930). "A Brief History of Field Museum from 1893 to 1930". Field Museum News. 1 (1): 1, 3.

- ^ Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Trustees for the Year 1906 (Report). Report Series. Vol. 3. Field Museum of Natural History. 1907. p. 99. Retrieved January 9, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Annual report of the Director to the Board of Trustees for the year 1906 (Report). Report Series. Vol. 3. Field Museum of Natural History. 1907. Plate XLIV. Retrieved January 9, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Field, S. (1943). Address of Mr. Stanley Field, president of the Museum. Chicago: Field Museum Press. pp. 3–5.

- ^ Field, S. (1943). "Fifty years of progress". Field Museum News. 14 (9/10): 3–10.

- ^ Webber, E. L. (1966). "Field Museum Again: name change honors Field Family". Field Museum of Natural History Bulletin. 37 (3): 2–3.

- ^ "Field Museum Changes Locations". May 20, 2009.

- ^ Ward, L. (1998). An explorer's guide to the Field Museum. Chicago, Illinois: The Field Museum.

- ^ Johnson, Steve (December 11, 2015). "Former Field Museum employee accused of stealing $900,000 over 7 years". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ TEA-AECOM Museum Index, published June 14, 2023.

- ^ "The Tsavo Lions". The Field Museum. June 23, 2014. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ jhoog (November 11, 2010). "Evolving Planet". The Field Museum. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ kangielczyk (March 16, 2011). "The Fossil Non-mammalian Synapsid Collection at The Field Museum". Field Museum. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ jhoog (November 11, 2010). "Inside Ancient Egypt". The Field Museum. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ Wojciechowski, Charlie. "New research at Field Museum peels back layers of the past for Egyptian remains". NBC Chicago. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ jhoog (January 11, 2011). "The Ancient Americas". The Field Museum. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ Hosmer, Brian (2008). "The Ancient Americas". The Public Historian. 30 (1): 142–145. doi:10.1525/tph.2008.30.1.142. JSTOR 10.1525/tph.2008.30.1.142.

- ^ McVicker, Donald (2003). "A Tale of Two Thompsons: The Contributions of Edward H. Thompson and J. Eric S. Thompson to Anthropology at the Field Museum". Fieldiana (36): 139–152. JSTOR 29782676.

- ^ Nash, Stephen (2003). "Paul Sidney Martin". Fieldiana (36): 165–177.

- ^ Haskin, Warren; Nash, Steven; Coleman, Sarah (2003). "A Chronicle of Field Museum Anthropology". Fieldiana (36): 65–81. JSTOR 29782670.

- ^ Swyers, Holly (2016). "Rediscovering Papa Franz: Teaching Anthropology and Modern Life". HAU Journal of Ethnographic Theory. 6 (2): 213–231. doi:10.14318/hau6.2.015. S2CID 151465357 – via Univ. of Chicago Press Open Access.

- ^ a b "Cyrus Tang Hall of China Exhibition Online". chinahall.fieldmuseum.org. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ "Africa". The Field Museum. August 24, 2011. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ swigodner (May 31, 2017). "Regenstein Halls of the Pacific". The Field Museum. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ "A Marae Abroad" (PDF). Gisbourne Herald. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 1, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ^ a b Lupton, Carter; Rathburn, Robert (1984). "Maritime Peoples of the Arctic and Northwest Coast. A Permanent Exhibit at the Field Museum of Natural History". American Anthropologist. 86 (1): 229–230. doi:10.1525/aa.1984.86.1.02a00790.

- ^ a b Kuta, Sarah (May 26, 2022). "Field Museum Confronts Its Outdated, Insensitive Native American Exhibition". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Demissie, Fassil; Apter, Andrew (1995). "An Enchanting Darkness: A New Representation of Africa". American Anthropologist. 97 (3): 559–566. doi:10.1525/aa.1995.97.3.02a00140. JSTOR 683275.

- ^ Codrington, Raymond (2003). "Wilfrid D. Hambly and Sub-Saharan Africa Research at the Field Museum, 1928–1953". Fieldiana. 36 (36): 153–163. JSTOR 29782677.

- ^ Rooney, Jessica; Kusimba, Chapurukha (2003). "The Legacy of James W. VanStone in Museum and Arctic Anthropology". Fieldiana (36): 221–234. JSTOR 29782682.

- ^ Bronson, Bennet (2003). "Berthold Laufer". Fieldiana (36): 117–126. JSTOR 29782674.

- ^ Collier, Donald (2003). "My Life with Exhibits at the Field Museum, 1941–1976". Fieldiana (36): 199–219. JSTOR 29782681.

- ^ Kaeppler, Adrienne (1991). "Untitled". American Anthropologist. 93 (1): 269–270. doi:10.1525/aa.1991.93.1.02a01100. JSTOR 681580.

- ^ Welsch, Robert (2003). "Albert Buell Lewis: Realizing George Amos Dorsey's Vision". Fieldiana. 36 (36): 99–115. JSTOR 29782673.

- ^ Kahn, Miriam (1995). "Heterotopic Dissonance in the Museum Representation of Pacific Island Cultures". American Anthropologist. 97 (2): 324–338. doi:10.1525/aa.1995.97.2.02a00100. JSTOR 681965.

- ^ jhoog (January 11, 2011). "Grainger Hall of Gems". The Field Museum. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ jhoog (January 11, 2011). "Elizabeth Hubert Malott Hall of Jades". The Field Museum. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ Heck, Philipp (November 12, 2014). "Fossil Meteorites Arrive at The Field Museum". Field Museum of Natural History. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ "Fossil Meteorites". meteorites.fieldmuseum.org. Field Museum. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ jsandy (July 22, 2014). "Underground Adventure". The Field Museum. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ "How well do you know SUE?". Field Museum of Natural History. August 11, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "Sue the T. Rex". Field Museum. February 5, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ "Sue at The Field Museum: The Largest, Most Complete, Best Preserved T. Rex". The Field Museum. 2007. Archived from the original on May 15, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ "I (SUE the T. rex) am moving to my own place and all y'all are invited" (Press release). Field Museum. January 30, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ Bauer, Kelly (December 18, 2018). "Sue the T. Rex Is Back at the Field Museum with a Huge New Suite". Block Club Chicago. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- ^ Shaffer, H. B.; Fisher, R. N.; Davidson, C. (1998). "The role of natural history collections in documenting species declines". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 13 (1): 27–30. Bibcode:1998TEcoE..13...27S. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01177-4. PMID 21238186.

- ^ Banks, R. C.; Clench, M. H.; Barlow, J. C. (1973). "Bird collections in the United States and Canada". Auk. 90: 136–170.

- ^ Lowther, P. (1995). Davis, W. E. Jr.; Jackson, J. A. (eds.). "Ornithology at the Field Museum. In: Contributions to the History of North American Ornithology". Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological Club. 12: 145–161.

- ^ Sturm, C. F.; Pearce, T. A.; Valdés, A. (2006). The Mollusks. A guide to their study, collection and preservation. Boca Raton, Florida: American Malacological Society, Universal Publishers. p. 445.

- ^ Poss SG, Collette BB (1995). "Second survey of fish collections in the United States and Canada". Copeia. 1995 (1): 48–70. doi:10.2307/1446799. JSTOR 1446799.

- ^ a b Meyer, A. B. (1905). Studies of the museums and kindred institutions of New York City, Albany, Buffalo, and Chicago, with notes on some European institutions [published in English, translated from German, in-depth comparative review of Field Museum exhibits, collections and operations around 1899–1900]. Smithsonian Institution, Government Printing office, No 138. pp. 311–608.

- ^ Collier, D. (1969). "Chicago Comes of Age: The World's Columbian Exposition and the Birth of Field Museum". Field Museum of Natural History Bulletin. 40 (5): 2–7.

- ^ "An historical and descriptive account of the Field Columbian Museum". Field Columbian Museum, Chicago, Pub. 1. 12 (1): 1–91. 1894.

- ^ a b Conn, S. (2010). Do museums still need objects?. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4190-7.

- ^ "Ward's Natural Science Establishment Papers". University of Rochester Libraries. 1876–1988. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ Akeley, C. (1920). In Brightest Africa. Garden City Publishers.

- ^ Field, Stanley (1943). Address of Mr. Stanley Field, president of the Museum. In: Three addresses. Chicago, Illinois: Field Museum Press. pp. 3–5.

- ^ Ewan, Joseph (1950). Rocky Mountain Naturalists. University of Denver Press. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ "Butterfly and Moth Collection: Herman Strecker Collection". The Field Museum. 2007. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ^ "Index Herbariorum". Steere Herbarium, New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- ^ Emerson, S. B. (1989). "Introduction, in: Emerson, S. B. (ed.) Contributions in celebration of the distinguished scholarship of Robert F. Inger on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday". Fieldiana, Zoology, Festschrift: v–vii.

- ^ Kong, C. P. (1989). "My field trip to Ulu Kinabatangnan, North Borneo, with Robert Inger, in: Emerson, S. B. (ed.) Contributions in celebration of the distinguished scholarship of Robert F. Inger on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday". Fieldiana, Zoology, Festschrift: vii–viii.

- ^ "Conserving Our Collections". The Field Museum. February 22, 2011. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ Bodry-Sanders, P. (1990). Carl Akeley: Africa's collector, Africa's savior. New York: Paragon House.

- ^ Solem, A. (1980). "Standards for malacological collections". Curator. 24 (1): 19–28. doi:10.1111/j.2151-6952.1981.tb00568.x.

- ^ Norton, R. E. (1996). A case history of managing outbreaks of Webbing Clothes Moth (Tineola bisselliella). Paris: Preprints of the ICOM C-C 11th Triennial Meeting. pp. 61–67.

- ^ Michalski, S. (1985). "A relative humidity control module". Museum (UNESCO). 146 (2): 85–88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0033.1985.tb00556.x.

- ^ Sease, C.; Anderson, C. (1994). Preventive conservation at the Field Museum" Preventive conservation: practice, theory and research. Preprints of the contributions to the Ottawa Congress, 12-16 September 1994. London, England: eds Roy, Ashok; Smith, Perry. International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. pp. 44–47.

- ^ Sease, C. (1990). "A new means of controlling relative humidity in exhibit cases". Collection Forum. 6 (1): 12–20.

- ^ Brown, J. P. (2010). "The Field Museum Archaeological Metals Project: Distributed, In Situ Micro-Environments for the Preservation of Unstable Archaeological Metals Using Escal® Barrier Film". Object Speciality Group Postprints. 17: 133–146.

- ^ Norton, R. E. (2003). "Dyeing Japanese paper with Fibre Reactive Dyes". The Paper Conservator. 26: 37–47. doi:10.1080/03094227.2002.9638621. S2CID 137546498.

- ^ Minderop, J.; Podsiki, C.; Norton, R. E. (2007). "Deinstallation and cleaning of the 1950s galleries of ethnographical and archaeological material from the Americas at the Field Museum, Chicago". Objects Specialty Group Postprints. 11: 103–125.

- ^ Klaus, M.; Plitnikas, J.; Norton, R. E.; Almazan, T.; Coleman, S. (2005). Poster abstract: Preliminary results from a survey for residual arsenic on the North American collections at The Field Museum, Chicago. Paris: ICOM: Preprints of the 14th Triennial Meeting The Hague. p. 127.

- ^ Podsiki, C.; Koch, I.; Lee, E.; Ollsen, C.; Reimer, K. (2002). Pesticide contaminated artifacts and the conservator. In Twenty-eighth annual ANAGPIC student conference: student papers: April 18–20, 2002. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Art Museums. Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. pp. 111–123.

- ^ Sease, C.; Berry, A. (1996). Expect the unexpected: early uses of plastic in ethnographic collections. Paris: In Preprints of the ICOM C-C 11th Triennial Meeting. pp. 639–642.

- ^ Sease, C.; Selwyn, L.; Zubiate, S.; Bowers, D.; Atkins, D. (1997). "Problems with coated silver: whisker formation and possible filiform corrosion". Studies in Conservation. 42: 1–10. doi:10.1179/sic.1997.42.1.1.

- ^ Sease, C. (1993). "Light piping: a new lighting system for museum cases". Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. 32 (3): 279–290. doi:10.1179/019713693806124884.

- ^ Bates, J. M.; Bowie, R. C. K.; Willard, D. E.; Voelker, G.; Kahindo, C. (2004). "A need for continued collecting of avian voucher specimens in Africa: Why blood is not enough". Ostrich. 75 (4): 187–191. Bibcode:2004Ostri..75..187B. doi:10.2989/00306520409485442. S2CID 5957433.

- ^ Bates, J. M.; Hackett, S. J.; Zink, R. M. (1993). Escalante-Pliego, P. (ed.). Tecnicas y materiales para la preservación de tejidos congelados. In: Curación moderna de colecciones ornitolólogicas. Washington, DC: American Ornithologists' Union. pp. 75–78.

- ^ Brewer, Logan Jaffe; Hudetz, Mary; Ngu, Ash; Lee, Graham (January 11, 2023). "America's Biggest Museums Fail to Return Native American Human Remains". ProPublica. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ National Science Foundation. "The Assessment of the Needs of Free-Standing Museums for the Computerization of Collections Management and Related Research, BSR-9118843, award summary". Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ^ "AntWeb". antweb.org.

- ^ "Free and Open Access to Biodiversity Data – GBIF.org". gbif.org.

- ^ "iDigBio Home". iDigBio.

- ^ Suarez, A. V.; Tsutsui, N. D. (2004). "The value of museum collections for research and society". BioScience. 54: 66–74. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0066:tvomcf]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Rea, P. M. (1910). "A directory of American Museums of Art, History and Science". Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences. 10 (1): 3–360.

- ^ "Invertebrates". The Field Museum. November 8, 2010. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ "Collections and Research Annual Reports". The Field Museum. Archived from the original on October 14, 2011.

- ^ "Research & Collections". The Field Museum. April 17, 2018. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ grings (January 13, 2011). "History of the Library". Field Museum. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Edward E. Ayer Ornithological Library; Field Museum of Natural History; Zimmer, John Todd; Osgood, Wilfred Hudson (1926). Catalogue of the Edward E. Ayer Ornithological Library. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Chicago, Illinois: Field Museum of Natural History.

- ^ "American Museum of Natural History Research Library: Laufer, Berthold 1874–1934 (amnhp_1001230)". data.library.amnh.org. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "World's Columbian Exposition of 1893". idaillinois.org.

- ^ "Urban Landscapes of Illinois: Digitization of Original Glass Negatives". The Field Museum. 2008. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ "Flickr: The Field Museum Library's Photostream". Flickr.

- ^ "Division of Amphibians and Reptiles". The Field Museum. November 8, 2010. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Williams, Benjamin W. "Audubon's The Birds of America and the Remarkable History of Field Museum's copy." Field Museum of Natural History Bulletin 57, no. 6 (June 1986): 7–21. www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/4352797.

- ^ "Harris Learning Collection". fieldmuseum.org. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013.

- ^ "EUFAR – The EUropean Facility for Airborne Research". eufar.net. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Staff – Emily Graslie". The Field Museum. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ "Culture". The Field Museum. November 2, 2010. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- ^ "Research & Collections: Botany". The Field Museum. 2007. Archived from the original on April 26, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ "Fossils & Meteorites". The Field Museum. November 8, 2010. Archived from the original on December 10, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- ^ "Animals". The Field Museum. October 27, 2010. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Academic Training & Research Education". The Field Museum. March 31, 2016.

- ^ "Fieldiana". Field Museum. Archived from the original on March 17, 2009. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

Bibliography

[edit]- Almazan, Tristan; Coleman, Sarah (2003). "George Amos Doresey: A Curator and His Comrades". Fieldiana. 36 (36): 87–97. JSTOR 29782672.

- Bronson, Bennet (2003). "Berthold Laufer". Fieldiana. 36 (36): 117–26. JSTOR 29782674.

- Codrington, Raymond (2003). "Wilfrid D. Hambly and Sub-Saharan Africa Research at the Field Museum, 1928–1953". Fieldiana. 36 (36): 153–163. JSTOR 29782677.

- Demissie, Fassil; Apter, Andrew (1995). "An Enchanting Darkness: A New Representation of Africa". American Anthropologist. 97 (3): 559–566. doi:10.1525/aa.1995.97.3.02a00140. JSTOR 683275.

- Hosmer, Brian (2008). "Untitled". The Public Historian. 30 (1): 142–45. doi:10.1525/tph.2008.30.1.142.

- Kaeppler, Adrienne (1991). "Untitled". American Anthropologist. 93 (1): 269–70. doi:10.1525/aa.1991.93.1.02a01100. JSTOR 681580.

- Kahn, Miriam (1995). "Heterotopic Dissonance in the Museum Representation of Pacific Island Cultures". American Anthropologist. 97 (2): 324–338. doi:10.1525/aa.1995.97.2.02a00100. JSTOR 681965.

- Kuta, Sarah (May 26, 2022). "Field Museum Confronts Its Outdated, Insensitive Native American Exhibition". Smithsonian Magazine.

- Lloyd, Timothy (2017). "The Cyrus Tang Hall of China: Deep Tradition, Dynamic Change". Museum Anthropology Review. 11 (1–2): 15–16. doi:10.14434/mar.v11i1.23543.

- Lupton, Carter; Rathburn, Robert (1984). "Maritime Peoples of the Arctic and Northwest Coast. A Permanent Exhibit at the Field Museum of Natural History". American Anthropologist. 86 (1): 229–230. doi:10.1525/aa.1984.86.1.02a00790.

- McVicker, Donald (2003). "A Tale of Two Thompsons: The Contributions of Edward H. Thompson and J. Eric S. Thompson to Anthropology at the Field Museum". Fieldiana. 36 (36): 139–152. JSTOR 29782676.

- Nash, Stephen (2003). "Paul Sidney Martin". Fieldiana. 36 (36): 165–177. JSTOR 29782678.

- Richter, Elizabeth (August 13, 2022). "Alaka Wali: Change Agent at the Field Museum". Classic Chicago Magazine.

- Welsch, Robert (2003). "Albert Buell Lewis: Realizing George Amos Dorsey's Vision". Fieldiana. 36 (36): 99–115. JSTOR 29782673.

- Yastrow, Ed; Nash, Stephen (2003). "Henry Field, Collections, and Exhibit Development, 1926–1941". Fieldiana. 36 (36): 127–138. JSTOR 29782675.