Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

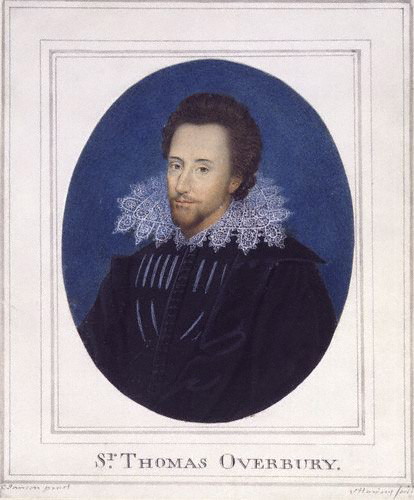

Thomas Overbury

View on Wikipedia

Sir Thomas Overbury (baptized 1581 – 14 September 1613) was an English poet and essayist, also known for being the victim of a murder which led to a scandalous trial. His poem A Wife (also referred to as The Wife), which depicted the virtues that a young man should demand of a woman, played a significant role in the events that precipitated his murder.[1]

Key Information

Background

[edit]Thomas Overbury was born near Ilmington in Warwickshire, a son of the marriage of Nicholas Overbury, of Bourton-on-the-Hill, Gloucester, and Mary Palmer.[2] In the autumn of 1595, he became a gentleman commoner of Queen's College, Oxford. He took his degree of BA in 1598, by which time he had already been admitted to study law in the Middle Temple in London.[3] He soon found favour with Sir Robert Cecil, travelled on the Continent, and began to enjoy a reputation for an accomplished mind and free manners.[2]

Robert Carr

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

About 1601, whilst on holiday in Edinburgh, he met Robert Carr, then an obscure page to the Earl of Dunbar. A great friendship was struck up between the two youths, and they came up to London together. Carr's early history is obscure, and it is probable that Overbury secured an introduction to court before his young associate contrived to do so. At all events, when Carr attracted the attention of James I in 1606 by breaking his leg in the tilt-yard,[4] Overbury had for some time been servitor-in-ordinary to the king.[citation needed]

Knighted by James in June 1608, from October 1608 to August 1609, he travelled in the Netherlands and France, staying in Antwerp and Paris; he spent at least some of this time with his contemporary, the Puritan theologian Francis Rous.[5]

Upon his return he began following Carr's fortunes very closely. When the latter was made Viscount Rochester in 1610, the intimacy seems to have been sustained. With Overbury's aid, the young Carr caught the eye of the King, and soon became his favourite and his lover. Overbury had the wisdom and Carr had the king's ear into which to pour it. The combination took Carr swiftly up the ladder of power. Soon he was the most powerful man in England next to Robert Cecil.[citation needed] However, Overbury and Rochester somehow offended Anne of Denmark in May 1611, and when she heard them laughing together in the garden at Greenwich Palace, she complained to the King that they laughed at her. Overbury was excluded from court for a few months.[6]

Court intrigues and death

[edit]

After the death of Cecil in 1612, the Howard party, consisting of Henry Howard, Thomas Howard, his son-in-law Lord Knollys, and Charles Howard, along with Sir Thomas Lake, moved to take control of much of the government and its patronage. The powerful Carr, unfit for the responsibilities thrust upon him and often dependent on his intimate friend, Overbury, for assistance with government papers,[7] fell into the Howard camp, after beginning an affair with the married Frances Howard, Countess of Essex, daughter of the Earl of Suffolk.[citation needed]

Overbury was from the first violently opposed to the affair, pointing out to Carr that it would be hurtful to his preferment, and that Frances Howard, even at this early stage in her career, was already "noted for her injury and immodesty." However, Carr was now infatuated, and he repeated to the Countess what Overbury had said. It was at this time, too, that Overbury wrote, and circulated widely in manuscript his poem A Wife, which was a picture of the virtues which a young man should demand in a woman before he has the rashness to marry her. Lady Essex believed that Overbury's object in writing this poem was to open the eyes of his friend to her defects. The situation now turned into a deadly duel between the mistress and the friend. The Countess tried to manipulate Overbury into seeming to be disrespectful to the queen, Anne of Denmark who took offence. Her chamberlain, Viscount Lisle, wrote in November 1612 that Overbury was allowed to come to court, but not in the queen's sight, or into her side of the royal lodgings.[8]

James I offered Overbury an assignment as ambassador, probably to the court of Michael of Russia, relations with Russia being at that time a potential issue between those who favoured a strongly pro-Protestant and anti-Catholic foreign policy, and those, centred on the Howards, who favoured accommodation with Catholic powers on the Continent; there were political reasons of international policy as well as personal ones involving the King's jealousy of Overbury's relationship with Carr, to persuade James to send the former away and also a private interest for Carr and the Earl of Northampton to urge the offer upon him. Overbury declined, possibly because he felt tricked into it by Carr (precisely because refusing would ensure that Overbury would be imprisoned),[9] possibly because Overbury sensed the urgency to remain in England and at his friend's side. James I was so irate at Overbury's arrogance in declining the offer that he had him thrown into the Tower of London on 22 April 1613, where he died on 14 September.[10]

Beginnings of scandal

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

The Howards won James's support for an annulment of Frances's marriage to Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, on grounds of impotence, to free her to remarry. With James's assistance, the marriage was duly annulled on 25 September 1613, despite Devereux's opposition to the charge of impotence. The commissioners judging the case reached a 5–5 verdict, so James quickly appointed two extra judges guaranteed to vote in favour, an intervention which aroused public censure. When, after the annulment, Thomas Bilson (son of Thomas Bilson, Bishop of Winchester, one of the added commissioners) was knighted, he was given the nickname "Sir Nullity Bilson".[11] There were also rumours that the commission was tricked into believing that Frances was still virgo intacta.[12]

The marriage two months later of Frances Howard and Robert Carr, now the Earl of Somerset, was the court event of the season, celebrated in verse by John Donne. The Howards' rise to power seemed complete.

Rumours of foul play in Overbury's death began circulating. Almost two years later, in September 1615, and as James was in the process of replacing Carr with new favourite George Villiers, the governor of the Tower sent a letter to the King, informing him that one of the warders had been bringing the prisoner "poisoned food and medicine."[13]

James showed a disinclination to delve into the matter, but the rumours refused to go away. Eventually, they began hinting at the King's own involvement, forcing him to order an investigation. The details of the murder were uncovered by Edward Coke and Sir Francis Bacon who presided over the trial.

Trial

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

In the celebrated trials of the six accused in late 1615 and early 1616 that followed, evidence of a plot came to light. It was very likely that Overbury was the victim of a 'set-up' contrived by the Earls of Northampton and Suffolk, with Carr's complicity, to keep him out of the way during the annulment proceedings. Overbury knew too much of Carr's dealings with Frances and, motivated by a deep political hostility to the Howards, opposed the match with a fervour that made him dangerous. The Queen had sown discord between the friends, calling Overbury Carr's "governor".

It was not known at the time, and it is not certain now, how much Carr participated in the first crime, or if he was ignorant of it. Lady Essex, however, was not satisfied with having had Overbury imprisoned; she was determined that "he should return no more to this stage." She had Sir William Wade, the honest Lord Lieutenant of the Tower, removed to make way for a new Lieutenant, Sir Gervase Helwys; and a gaoler, Richard Weston, of whom it was ominously said that he was "a man well acquainted with the power of drugs", was set to attend on Overbury. Weston, afterwards aided by Mrs Anne Turner, the widow of a physician, and by an apothecary called Franklin, plied Overbury with sulfuric acid in the form of copper vitriol.

It cannot have been difficult for the conspirators to secure James's compliance because he disliked Overbury's influence over Carr.[14] John Chamberlain (1553–1628) reported at the time that the King "hath long had a desire to remove him from about the lord of Rochester [Carr], as thinking it a dishonour to him that the world should have an opinion that Rochester ruled him and Overbury ruled Rochester".[15] Overbury had been poisoned.[16]

Frances Howard admitted a part in Overbury's murder, but her husband did not. Fearing what Carr might say about him in court, James repeatedly sent messages to the Tower pleading with him to admit his guilt in return for a pardon. "It is easy to be seen that he would threaten me with laying an aspersion upon me of being, in some sort, accessory to his crime".[17]

In late May 1616, the couple were found guilty and sentenced to death for their parts in this conspiracy. Nevertheless, they remained prisoners in the Tower until eventually released in 1622 and pardoned.[18]

Four accomplices – Richard Weston, Anne Turner, Gervaise Helwys and Simon Franklin – were found guilty prior to that in 1615 and, lacking powerful connections, were hanged.[19]

The implication of the King in such a scandal provoked much public and literary conjecture and irreparably tarnished James's court with an image of corruption and depravity.[20]

Aftermath

[edit]The dramatist John Ford wrote a lost work titled Sir Thomas Overbury's Ghost, containing the history of his life and untimely death (1615). Its nature is uncertain, but Ford scholars have suggested it may have been an elegy, prose piece or pamphlet.[21]

See also

[edit]- The Cobbe portrait, frequently cited as one of a very few portraits of William Shakespeare, is believed by several scholars to be a portrait of Overbury instead.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Thomas Overbury, A Wife retrieved 1 October 2014

- ^ a b "Overbury, Sir Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20966. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Alumni Oxonienses 1500-1714".

- ^ Poltrack, Emma. "A world of poison: The Overbury scandal", Shakespeare & Beyond, Folger Shakespeare Library, 16 October 2018

- ^ McGee 2004, p. 406.

- ^ Jackie Watson, Epistolary Courtiership and Dramatic Letters: Thomas Overbury and the Jacobean Playhouse (Edinburgh University Press, 2024), pp. 60, 77: A. B. Hinds, HMC Downshire, 3 (London: HMSO, 1938), pp. 83, 180.

- ^ Willson, pg. 349; "Packets were sent, sometimes opened by my lord, sometimes unbroken unto Overbury, who perused them, registered them, made table-talk of them, as they thought good. So I will undertake the time was, when Overbury knew more of the secrets of state, than the council-table did." Francis Bacon, speaking at the trial. Quoted by Perry, p. 105.

- ^ William Shaw & G. Dyfnallt Owen, HMC 77 Viscount De L'Isle Penshurst, vol. 5 (London, 1961), p. 65.

- ^ Dunning, Chester. "The Fall of Sir Thomas Overbury and the Embassy to Russia in 1613", The Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 22, no. 4, 1991, pp. 695–704. JSTOR. Accessed 30 July 2020.

- ^ Annabel Patterson. Reading Between the Lines (Madison, Wis., 1993), p. 195.

- ^ Lindley, pg. 120.

- ^ Weldon, Anthony, The Court and Character of King James, 1650, pp. 73–74. Accessed 30 July 2020.

- ^ Barroll, Anna of Denmark, p 136.

- ^ Lindley, p. 145

- ^ Willson, p. 342.

- ^ Lindley, p. 146.

- ^ Stewart, p. 275.

- ^ The Overbury Murder Scandal (1615–1616) earlystuartlibels.net. Accessed 29 August 2022.

- ^ The Overbury Murder Scandal (1615–1616) earlystuartlibels.net. Accessed 29 August 2022.

- ^ Underdown, David. "Review of Bellany, Alastair, The Politics of Court Scandal: News Culture and the Overbury Affair, 1603–1660", H-net.org. May 2002.

- ^ Stock, L. E., et al. (eds.) The Nondramatic Works of John Ford (Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1991); p. 340.

References

[edit]- Barroll, J. Leeds (2001) Anna of Denmark, Queen of England: a cultural biography. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press ISBN 0-8122-3574-6.

- Davies, Godfrey ([1937] 1959) The Early Stuarts. Oxford: Clarendon Press ISBN 0-19-821704-8.

- DeFord, Miriam Allen (1960) The Overbury Affair: the murder trial that rocked the court of King James I. Philadelphia: Chilton Company.

- Harris, Brian (2010 ) Passion, Poison and Power: The Mysterious Death of Sir Thomas Overbury Wildy, Simmonds and Hill. ISBN 9780854900770.

- Lindley, David (1993) The Trials of Frances Howard: fact and fiction at the court of King James. London: Routledge ISBN 0-415-05206-8.

- McGee, Sears J (2004). "Francis Rous and "scabby or itchy children": The Problem of Toleration in 1645". Huntington Library Quarterly. 67 (3). doi:10.1525/hlq.2004.67.3.401.

- Perry, Curtis (2006) Literature and Favoritism in Early Modern England. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-85405-9.

- Stewart, Alan (2003) The Cradle King: a life of James VI & I. London: Chatto and Windus. ISBN 0-7011-6984-2.

- Willson, David Harris ([1956] 1963 ed) King James VI & I. London: Jonathan Cape ISBN 0-224-60572-0.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gosse, Edmund William (1911). "Overbury, Sir Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). p. 384.

External links

[edit]- The tryal of Mr. Richard Weston, at the Guild-Hall of the City of London, for the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury, Knt. October the 19th, 1615. 13 Jac. I, 1737 (unknown author, publisher)

Thomas Overbury

View on GrokipediaSir Thomas Overbury (1581 – 15 September 1613) was an English poet, essayist, and courtier whose posthumously published work A Wife, a verse portrait of the ideal spouse appended with satirical prose Characters depicting various social types, achieved significant literary success and helped popularize the character-writing genre in English literature.[1][2]

Overbury's close friendship and advisory role to Robert Carr, a favorite of King James I who rose to become Earl of Somerset, positioned him at the heart of Jacobean court politics, where he opposed Carr's romantic entanglement with Frances Howard, Countess of Essex, whose prior marriage was controversially annulled on grounds of impotence.[3][1] When Overbury refused a diplomatic post intended to remove him from influence and publicly criticized the match—interpreting his poem A Wife as an indirect attack on Howard—he was imprisoned in the Tower of London on 21 April 1613 for "contempt of the king's authority."[2][3]

Overbury died in agony on 15 September 1613 after months of systematic poisoning administered through tainted food, drink, and enemas containing substances like arsenic, mercury sublimate, and nitric acid, a plot orchestrated by Howard with accomplices including apothecary Simon Weston and facilitated by lax oversight from Tower lieutenant Sir Gervase Elwes.[2][3] The ensuing Overbury Affair, uncovered in 1615, led to trials in 1616 that convicted Howard, Carr, and Elwes of murder—though the principals received royal pardons after imprisonment—while exposing corruption and factionalism at court, resulting in the execution of several lesser conspirators and marking a pivotal scandal under James I's reign.[3][2]

Early Life

Birth, Family, and Education

Thomas Overbury was baptized on 18 June 1581 at Compton Scorpion, near Ilmington in Warwickshire, England.[4] He was the son of Nicholas Overbury (c. 1549–1643), a prosperous landowner of Bourton-on-the-Hill in Gloucestershire who later served as a justice of the peace and member of Parliament, and Mary Palmer, daughter of Walter Palmer of Leamington Hastings, Warwickshire.[5] [4] Overbury was the eldest surviving son among his siblings, with accounts varying on the total number of children in the family, one estimating ten.[6] [7] In autumn 1595, at age 14, Overbury matriculated as a gentleman commoner at Queen's College, Oxford, where he received a classical education typical for sons of the gentry.[1] He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1598 without proceeding to a master's, reflecting the common practice for those intending public careers rather than clerical ones.[1] Following Oxford, Overbury moved to London to study law at the inns of court, though he did not complete formal legal training and instead pursued opportunities at court.[1]Court Career

Association with Robert Carr

Thomas Overbury met Robert Carr around 1601 in Edinburgh, where the younger Carr, then a page to the Earl of Dunbar, impressed the university-educated Overbury with his ambition and charm.[1][8] Their acquaintance deepened into a close friendship as Carr accompanied James VI to London upon his accession as James I in 1603, and Overbury soon assumed the role of Carr's secretary and confidant.[2] Overbury's intellectual acumen complemented Carr's social graces, positioning the pair as influential figures in the emerging Jacobean court. As Carr gained prominence—particularly after suffering a severe injury during a 1607 tilting tournament that drew the king's personal attention—Overbury served as his primary advisor, supplying political insights and drafting communications that enhanced Carr's standing with James.[9] This mentorship propelled Carr's ascent: he was knighted in 1607, elevated to Gentleman of the Bedchamber, and created Viscount Rochester on March 4, 1611.[10] Overbury's contributions extended to behind-the-scenes maneuvering, allowing him to wield considerable indirect power through Carr's favor, which culminated in Overbury's own knighthood in June 1608.[11] The association granted Overbury access to court patronage and intellectual circles, where he leveraged their partnership to advance shared interests, though it also fostered dependencies that later strained under competing ambitions.[8] Historians note Overbury's role as mentor was pivotal in navigating the factional intrigues of James's court, with Carr relying on Overbury's counsel for key decisions until tensions arose over Carr's prospective marriage.[3]Positions and Influence at Court

Sir Thomas Overbury gained prominence at the court of King James I primarily through his close association with Robert Carr, the king's favorite, serving as Carr's secretary, mentor, and political advisor from around 1606. Overbury drafted correspondence, provided strategic counsel on court politics and foreign affairs, and helped transform Carr from a courtier reliant on personal charm into a figure of apparent statesmanship. This advisory role amplified Overbury's indirect influence over royal decisions, as Carr's access to the king allowed them to shape patronage networks.[12][13] Overbury acted as an intermediary for suitors seeking Carr's intercession with the king, facilitating the flow of bribes and promotions; those unable or unwilling to pay often faced exclusion from favor. In recognition of his proximity to power, King James granted Overbury financial support in 1606 and a lease on a saltworks in 1607. He was knighted in June 1608, marking his elevated status at court, though he held no major formal office beyond informal roles like servitor-in-ordinary to the king.[8][14] By 1611, Overbury's influence peaked alongside Carr's creation as Viscount Rochester, with the pair wielding significant sway over court appointments and policy alignments, including Carr's temporary shift toward Protestant interventionist factions. Overbury's writings and observations on court characters further reflected his insider perspective, though his opposition to certain alliances foreshadowed conflicts. This influence, however, derived almost entirely from Carr's favor rather than independent royal appointment.[15][12]The Carr-Howard Marriage Controversy

Frances Howard's Divorce

Frances Howard, Countess of Essex, petitioned for the nullity of her marriage to Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, in 1613 on the grounds of non-consummation attributable to Devereux's impotence. The union had been contracted on 25 January 1606, when Howard was 13 years old and Devereux 14, but remained unconsummated throughout its duration, as Howard alleged Devereux's persistent failure to perform sexually despite repeated attempts.[2][16] Devereux countered that any impotence was specific to Howard, asserting successful intercourse with other women, and suggested possible frigidity or sorcery on her part as contributing factors.[17][18] On 17 May 1613, Howard's father, Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk, and uncle, Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, filed the suit on her behalf before King James I, who delegated the matter to a commission of 22 delegates, including Archbishop of Canterbury George Abbot, to adjudicate under canon law, where impotence constituted the primary basis for nullity in unconsummated marriages. Proceedings commenced in June 1613 but recessed amid controversy, reconvening in September. Evidence included witness testimonies: Devereux presented accounts from associates affirming his potency elsewhere, while Howard underwent examination by a panel of matrons, who certified her virginity, bolstering her claim of non-consummation.[16][18][19] The commission's deliberations were marked by intense scrutiny and public scandal, with Devereux's defense highlighting relational discord rather than absolute incapacity, yet the panel rendered a divided verdict of 7 to 5 in favor of nullity on 25 September 1613, just eleven days after the death of Sir Thomas Overbury, a vocal opponent of the proceedings.[18][19] The outcome, influenced by court favoritism toward Howard's intended union with Robert Carr, Viscount Rochester, provoked widespread outrage, libelous pamphlets, and debates over evidentiary credibility, including skepticism toward the matrons' examination and Devereux's selective impotence claim.[18][20]Overbury's Opposition and Dismissal

Sir Thomas Overbury, as secretary and close advisor to Robert Carr (Viscount Rochester), strongly opposed Carr's intended marriage to Frances Howard, Countess of Essex, during her divorce proceedings from Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, in early 1613.[2] Overbury viewed the union as detrimental to Carr's reputation and career prospects, arguing that Howard's character and the political entanglement with the powerful Howard family—known for factional maneuvering at court—would undermine Carr's independent influence with King James I.[21] His counsel emphasized the risks of aligning with a family whose ambitions could subordinate Carr's favor, reflecting Overbury's broader strategy to preserve Carr's unencumbered access to royal patronage.[18] Overbury's resistance manifested in direct admonitions to Carr and indirect critiques, including his character sketch A Wife (composed circa 1613 and published posthumously in 1614), which idealized virtuous womanhood in terms that contemporaries interpreted as a veiled indictment of Howard's reputed frivolity and moral laxity.[2] This opposition fueled personal animosity from Howard, who perceived Overbury as an obstacle to her remarriage, and strained his longstanding friendship with Carr, who prioritized the alliance despite Overbury's warnings.[22] Court gossip at the time highlighted Overbury's marginalization, with efforts to avoid his public "banishment and loss of office" amid growing pressure from Carr and Howard's supporters.[6] By April 1613, Overbury's influence waned as Carr distanced himself, leading to Overbury's effective dismissal from court circles through exclusion and an offer of ambassadorship to Russia—a posting designed to sideline him during the contentious divorce.[3] Suspecting the offer as a maneuver to neutralize his interference, Overbury refused the position, resulting in his commitment to the Tower of London on April 21, 1613, on charges of contempt toward the king.[3] This act formalized his removal from court, severing his advisory role and exposing him to isolation amid the escalating Carr-Howard intrigue.[2]Imprisonment and Death

Refusal of Ambassadorship and Confinement

In April 1613, amid growing opposition to Robert Carr's marriage to Frances Howard, King James I offered Sir Thomas Overbury the post of ambassador to Russia, a diplomatic mission intended to distance him from court influences and Carr's affairs. [23] Overbury declined the appointment, viewing it as a maneuver to curtail his advisory role over Carr and potentially exile him from key political circles.[2] [24] James I, interpreting the refusal as an affront to royal authority and an act of contempt, ordered Overbury's arrest on 21 April 1613.[3] Overbury was promptly conveyed to the Tower of London, where he was held without formal trial under the king's direct prerogative, ostensibly for his insubordination in rejecting the ambassadorship.[11] This confinement severed Overbury's direct access to Carr and court, aligning with efforts by Howard's allies to neutralize his interference in the union.[21]Conditions in the Tower and Final Days

Sir Thomas Overbury was committed to the Tower of London on 21 April 1613 for contempt of court after refusing King James I's offer of an ambassadorship to Russia, intended to remove him from court influence.[3] He was placed under the authority of the Tower's lieutenant, Sir Gervase Elwes (also spelled Helwys), whose appointment had been secured through the influence of Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton, a relative of Frances Howard.[3] As a prisoner of gentle birth, Overbury initially received accommodations befitting his status, including some access to writing materials and restricted correspondence, though visitors were limited and monitored.[2] Richard Weston was appointed as Overbury's personal keeper shortly after his arrival, a position that allowed him to control the prisoner's daily sustenance and medical treatments.[2] Under instructions influenced by Overbury's enemies, including Frances Howard's intermediaries, Weston's oversight involved severe dietary restrictions, confining Overbury largely to bread, water, and minimal provisions, which deviated from standard treatment for high-status inmates.[3] Overbury composed letters from his cell decrying the harsh conditions and his keeper's neglect or active cruelty, though these communications were intercepted or suppressed.[3] Poisoning commenced in May 1613, with Weston administering sublimate of mercury, arsenic, and nitric acid in small doses via contaminated food such as tarts and jellies, as well as in emetics and a fatal enema procured from apothecary Simon Franklin.[3][2] These toxins induced a protracted decline, marked by recurrent fluxes, vomiting, and excruciating pain, weakening Overbury over the ensuing months despite occasional interventions by Elwes to provide better fare or physicians.[3] In his final days, Overbury endured intense agony, confined to his bed amid unrelenting symptoms until his death on 15 September 1613, just ten days before Frances Howard's divorce was finalized.[2] An immediate post-mortem examination by attending physicians revealed his stomach covered in yellow pustules, his back discolored an unnatural brown, and an overpowering stench emanating from his body, indicators later recognized as consistent with chronic mercurial poisoning.[3] At the time, his demise was attributed to natural causes or prison hardships, with suspicions of foul play emerging only in subsequent investigations.[3]The Poisoning Scandal

Evidence of Foul Play

Overbury's death on 15 September 1613 followed a period of acute suffering in the Tower of London, where he had been confined since April of that year for refusing an ambassadorship, a maneuver linked to his opposition to Robert Carr's impending marriage to Frances Howard.[3] His decline involved prolonged agony, with contemporary accounts noting severe distress consistent with chronic toxic exposure, though initially attributed to natural causes or prison conditions.[3] Post-mortem observations provided the earliest tangible indicators of unnatural causes: his stomach was found covered in yellow pustules, his back exhibited an unnatural brownish discoloration, his throat was ulcerated, and the body emitted an appalling stench shortly after death.[3] These signs, while not immediately prompting investigation, deviated from typical ailments of the era and aligned retrospectively with the effects of ingested corrosives and metallics, such as those later identified in related trials. The circumstantial context amplified doubts: Overbury's imprisonment had been orchestrated amid court intrigues, including his counsel against Howard's divorce from the Earl of Essex, and he died just ten days before the annulment was finalized, removing a key obstacle for Carr and Howard.[2] Special foods, jellies, and remedies supplied from court—ostensibly for his comfort—were under the influence of Carr's associates, creating opportunities for tampering that fueled later scrutiny.[2] Rumors of an "unnatural death" persisted in the months following, driven by Overbury's prominence and the opacity of his Tower treatment, though these did not coalesce into formal suspicion until 1615.[2] The absence of an autopsy at the time, combined with the political stakes, delayed recognition of these elements as evidence of deliberate harm.[3]Investigations and Confessions

In late 1615, following the waning influence of Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset, and amid growing suspicions at court, King James I initiated an investigation into Overbury's death, prompted by reports of irregularities in his Tower confinement.[3] The probe began with the interrogation of Gervase Helwys, Lieutenant of the Tower, by diplomat Ralph Winwood; under examination, Helwys confessed to receiving instructions from powerful figures, including the Earl of Northampton and Thomas Howard, Earl of Suffolk, to ensure Overbury's death by denying him medical care and facilitating mistreatment, though he denied direct involvement in poisoning.[25] Richard Weston, Overbury's under-keeper and gaoler, was arrested shortly thereafter and subjected to torture on the rack; he confessed to administering multiple poisons over months, including white arsenic in Overbury's food and drink starting in June 1613, followed by mercury sublimate (calomel) and a corrosive substance identified as diamort or aqua fortis (nitric acid), often via enemas to exploit Overbury's dysentery-like symptoms.[26][25] Weston implicated Anne Turner, a confidante of Frances Howard, as the source of the poisons, which she procured through apothecary assistants like Simon Franklin, who later confessed to delivering the substances under her directions.[2] Helwys's and Weston's confessions under duress extended the inquiry to Frances Howard, Countess of Somerset, who admitted procuring the poisons—specifically requesting "to kill a man unknown" from Turner—and coordinating their delivery to the Tower, motivated by Overbury's opposition to her marriage; she denied intent to kill but acknowledged negligence in Overbury's care.[27] Howard's partial confession, extracted amid threats of further scrutiny, shifted blame partially to intermediaries while implicating her husband's knowledge, though Somerset maintained ignorance throughout.[28] These admissions, corroborated by physical evidence like residual poisons in Overbury's body noted in post-revelation examinations, confirmed a deliberate regimen of toxic dosing from April to September 1613, leading to the execution of Weston, Helwys, Turner, and Franklin in November and December 1615.[3][25]Trials and Aftermath

Prosecution of the Somersets

The prosecution of Frances Howard, Countess of Somerset, and her husband Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset, followed the convictions and executions of their alleged subordinates in the poisoning of Sir Thomas Overbury. After King James I authorized an investigation in September 1615, led by figures including Edward Coke, confessions from Richard Weston (Overbury's jailer), Anne Turner, apothecary James Franklin, and Tower Lieutenant Sir Gervase Elwes implicated the Somersets in directing the administration of poisons such as sublimate of mercury and diamorphine via tainted foods and enemas during Overbury's confinement in 1613.[29][2] These accomplices were tried, convicted, and hanged between mid-October and early December 1615, providing testimonial evidence that Frances had orchestrated the deliveries through intermediaries, while Carr's foreknowledge remained contested but was inferred from his role in Overbury's imprisonment.[29][20] The Somersets were arrested on 17 October 1615 and held in the Tower of London pending trial.[20] Their cases proceeded to Westminster Hall after delays amid political maneuvering at court. Frances Howard was arraigned on 24 May 1616 before a jury of peers, where Attorney General Sir Francis Bacon presented the chain of confessions linking her to the procurement and dispatch of poisons; she pleaded guilty to the murder but asserted Carr's innocence, claiming sole responsibility to shield him.[2][20] The jury convicted her swiftly, sentencing her to death by hanging.[29] Carr's trial followed on 25 May 1616, with Bacon again prosecuting, emphasizing circumstantial evidence including Carr's opposition to Overbury's release from the Tower and intercepted letters suggesting awareness of the plot.[2] Carr pleaded not guilty, denying direct involvement or knowledge of the poisons, and his defense highlighted the lack of material proof tying him to the acts beyond association.[2] Despite this, the peer jury found him guilty of felony murder, imposing the death penalty; contemporaries noted the verdict's basis in the subordinates' implicating testimonies and the couple's motives tied to Overbury's disapproval of their union.[29][20] King James I intervened post-verdict, commuting both sentences to indefinite imprisonment in the Tower to avert execution and forestall further revelations damaging to the court; Frances received a pardon in 1622, while Carr remained confined until 1625.[29][20] The proceedings exposed systemic favoritism under James's reign but were criticized for relying heavily on coerced confessions from the underlings, though the Somersets' guilt in facilitating Overbury's demise aligned with the empirical chain of administered toxins confirmed at autopsy and trial.[2]Convictions, Pardons, and Political Ramifications

Frances Howard, Countess of Somerset, was tried for the murder of Overbury on May 24, 1616, at Westminster Hall, where she pleaded guilty to the charge of procuring his poisoning through tainted food and medicines administered in the Tower of London.[30] Her husband, Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset, faced trial shortly thereafter in 1616, denying involvement but convicted based on circumstantial evidence linking him to the conspiracy, including his knowledge of the plot and failure to intervene.[31] Both were found guilty of petty treason and murder, receiving death sentences that prescribed hanging, drawing, and quartering for Somerset and burning at the stake for Frances, though execution was not carried out.[23] King James I intervened decisively, commuting their death sentences to lifelong imprisonment in the Tower of London, a decision influenced by his lingering affection for Somerset as a former favorite and reluctance to execute high nobility amid court pressures.[8] The couple remained confined until January 1622, when they were released under a royal pardon, with formal documentation following in 1624, allowing them to retire to private estates without further punishment.[28] This clemency extended to lesser accomplices like the apothecary Simon Franklin and jailer Richard Weston, who confessed under torture and were hanged in 1615, while the full pardon for the principals spared the crown from executing peers potentially tied to broader factional networks.[11] The Overbury affair precipitated significant political fallout, eroding public trust in James I's judgment by exposing favoritism toward courtiers like Somerset, whose influence had warped judicial processes, including the king's role in Overbury's initial confinement against legal advice.[23] Pamphlets, ballads, and news-sheets proliferated, portraying the court as a den of corruption, poison, and moral inversion, which fueled anti-court sentiment among elites and commons alike, signaling a perceived decay in Jacobean values.[32] Somerset's disgrace accelerated the ascent of George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, as the new royal favorite, reshaping court factions and highlighting the perils of unchecked patronage, while the scandal's resolution via pardon compromised the king's image as an impartial arbiter, inviting critiques of arbitrary mercy over justice.[8]Literary Contributions

Key Works and Themes

Overbury's most prominent literary work is the poem A Wife, first published in 1614 shortly after his death, which quickly achieved popularity with multiple editions appearing within the year.[33] The poem outlines the ideal qualities of a wife, portraying her as a paragon of moral virtue, domestic competence, and intellectual compatibility rather than mere physical allure, with lines asserting that "All the carnall beauty of my wife is but skin deep."[33] Themes center on the primacy of chastity, fidelity, and rational partnership in marriage, contrasting lustful passion with enduring, reason-based affection, while cautioning against superficial attractions that lead to vice.[33] Appended to early editions of A Wife and expanded in subsequent printings, Overbury's prose Characters consist of witty, satirical sketches depicting archetypal figures from society, such as "A Fair and Happy Milk-maid," "A Hypocrite," and "A Reverend Judge."[33] Initially comprising around 21 pieces in 1614, the collection grew to over 60 by later editions like the ninth in 1616, though some additions were by other authors.[33] These vignettes employ concise, observational prose to critique human foibles, professional pretensions, and social roles, blending moral instruction with humor to expose hypocrisy, vanity, and ethical lapses in courtly and everyday life.[33] Another notable prose work, Sir Thomas Overbury his Observations in his Travailes upon the State of the XVII Provinces as they stood Anno Dom. 1609, appeared in 1626, drawing from Overbury's continental journeys to analyze the political, economic, and military conditions of the Low Countries amid the Twelve Years' Truce.[34] Its themes emphasize pragmatic governance, the interplay of war and peace, and the strengths of republican structures over absolutism, reflecting Overbury's interest in statecraft informed by direct experience rather than abstract theory.[34] Across these works, Overbury's style favors terse, epigrammatic expression suited to moral and social commentary, influencing the character-writing genre in English literature.[33]"A Wife" and Character Sketches

"A Wife", a poem attributed to Overbury, outlines the virtues of an ideal spouse, emphasizing modesty, chastity, domestic competence, and intellectual restraint in women, while portraying her as a supportive partner who avoids excessive learning or public ambition.[2] [35] First entered in the Stationers' Register on December 1, 1613, it appeared posthumously in print in 1614 under the title Sir Thomas Overbury His Wife, with the subtitle A Wife, Now the Widow of Sir Thomas Overbury.[35] The work circulated in manuscript at court prior to publication, reflecting Jacobean ideals of femininity rooted in Protestant conduct literature, where the wife's role centers on moral purity and household management rather than scholarly pursuits.[35] Overbury contrasts this paragon against vices like ostentation or flirtation, using vivid metaphors—such as likening her beauty to "the rose that in the month of May doth bud"—to advocate for a balanced, unpretentious character.[35] Appended to the 1614 edition of A Wife were initial character sketches, brief prose vignettes describing archetypal figures from English society, such as "A Good Wife", "A Fair and Happy Milkmaid", and "A Very Merry Drunkard".[36] These sketches, totaling 21 in the first printing, employ witty, satirical observations influenced by Joseph Hall's earlier Characters of Virtues and Vices (1608), but shift toward secular, courtly humor with concise, epigrammatic style that dissects social types through their habits, flaws, and virtues.[37] Subsequent editions rapidly expanded the collection: the 1615 version added 32 anonymous "New Characters", reaching over 80 by 1616, with contributions from contemporaries including John Webster, Thomas Dekker, and Richard Brathwait, though Overbury is credited as the primary compiler.[38] Authorship of individual sketches remains debated, as the collaborative nature blurred lines, but the Overburian series established a template for the genre, blending moral critique with observational realism drawn from urban and rural life.[36] The characters' literary significance lies in popularizing the form as a vehicle for social commentary, bridging sermon-like moralizing with tavern wit, and influencing later writers like Samuel Butler and John Earle.[37] Examples include "An Ostler", portraying a horse-handler's cunning deceit, and "A Prison", anthropomorphizing confinement as a corrupting influence—reflecting Overbury's own Tower experiences without direct reference.[38] This vogue for characters filled a niche for portable, entertaining moral essays, with Overbury's editions selling widely and spawning imitations, though modern assessments note their occasional coarseness and reliance on period stereotypes over deep psychological insight.[39]Legacy

Cultural and Literary Influence

Overbury's poem A Wife, outlining the virtues expected in an ideal spouse, circulated in manuscript form prior to his imprisonment and gained widespread posthumous acclaim following its 1614 publication, with six editions issued within the first year alone.[40] The notoriety surrounding his poisoning amplified demand, propelling the work through multiple impressions, including a sixteenth edition by the early seventeenth century, and sustaining its availability well into the period.[40] [41] Subsequent editions incorporated brief prose sketches known as "characters," initially numbering around 21 additions by anonymous contributors, eventually expanding to 82 in later compilations, which shifted focus from the poem to these satirical vignettes of social types, professions, and vices.[42] These Overburian characters exemplified and popularized the genre of concise moral and observational portraits in English prose, drawing from classical models like Theophrastus while adapting them to contemporary courtly and urban life, thereby influencing vernacular literary traditions through their rhetorical emphasis on typology and satire.[43] [44] The format's appeal lay in its blend of wit and social commentary, inspiring imitators such as John Earle and contributing to a broader wave of character-writing that documented seventeenth-century English manners, professions, and national stereotypes, with Overbury's collection often credited as the inaugural and most enduring sequence in the vernacular.[37] [45] This legacy extended to parodic and dramatic applications, embedding character sketches in plays and essays as tools for critiquing societal roles and behaviors.[44]Historical Assessments and Debates

Historians concur that Sir Thomas Overbury's death on September 14, 1613, resulted from systematic poisoning orchestrated by Frances Howard, Countess of Somerset, using subordinates such as Richard Weston, who administered toxic substances including mercury sublimate and diamorphine mixtures over several months.[29] This assessment rests on confessions extracted during the 1615-1616 investigations, including those of executed accomplices like Weston and Anne Turner, and the subsequent trials where Howard admitted her role while denying direct administration.[11] Contemporary records, including autopsy findings of corrosive effects on Overbury's organs, support foul play over natural causes like the initially suspected "hot distemper."[3] Debate persists regarding Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset's precise culpability, with evidence indicating his awareness and indirect facilitation—such as influencing Overbury's Tower imprisonment—though prosecutors emphasized Howard's initiative to eliminate Overbury's opposition to their marriage.[12] Alastair Bellany argues in his analysis that Somerset's conviction reflected political expediency amid factional rivalries, yet his pardon by James I in 1622 underscores assessments of royal favoritism compromising justice, as the king prioritized shielding a former intimate from execution despite public outrage.[46] Some early modern libels speculated James's direct involvement, a view echoed in fringe interpretations but rejected by scholars for lacking empirical support, attributing such claims to anti-court propaganda exploiting Jacobean patronage scandals.[29] The Overbury affair is historiographically interpreted as a catalyst exposing systemic corruption in James I's court, fueling a burgeoning news culture of pamphlets and verses that politicized the event, linking it to broader anxieties over Catholic intrigue via the "powder poison" motif and moral decay among favorites.[47] Bellany's study traces its resonance through 1660, portraying it as amplifying opposition narratives that eroded monarchical legitimacy, though causal links to later upheavals like the English Civil War remain contested, with evidence pointing more to symptomatic rather than precipitating effects on public distrust of Stuart governance.[23] Assessments emphasize the scandal's role in highlighting causal dynamics of unchecked favoritism, where personal vendettas intersected with state power, without systemic bias in primary judicial records undermining the poisoning verdict.[46]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography%2C_1885-1900/Overbury%2C_Thomas