Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Docodonta

View on Wikipedia

| Docodontans Temporal range: Early Jurassic–Early Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

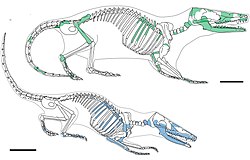

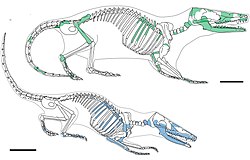

| Skeletal diagrams of Borealestes serendipitus (green) and B. cuillinensis (blue) from the Middle Jurassic of Scotland. Scale bars = 10 mm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | Cynodontia |

| Clade: | Mammaliaformes |

| Order: | †Docodonta Kretzoi, 1946 |

| Genera | |

|

See text. | |

Docodonta is an order of extinct Mesozoic mammaliaforms (advanced cynodonts closely related to true crown-group mammals). They were among the most common mammaliaforms of their time, persisting from the Early Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous across the continent of Laurasia (modern-day North America, Europe, and Asia). They are distinguished from other early mammaliaforms by their relatively complex molar teeth.

Docodontan teeth have been described as "pseudotribosphenic": a cusp on the inner half of the upper molar grinds into a basin on the front half of the lower molar, like a mortar-and-pestle. This is a case of convergent evolution with the tribosphenic teeth of therian mammals. There is much uncertainty for how docodontan teeth developed from their simpler ancestors. Their closest relatives may have been certain Triassic "symmetrodonts", namely Woutersia, and Delsatia.[1] The shuotheriids, another group of Jurassic mammaliaforms, also shared some dental characteristics with docodontans. One study has suggested that shuotheriids are closely related to docodontans,[2] though others consider shuotheriids to be true mammals, perhaps related to monotremes.[3]

For much of their history of study, docodontan fossils were represented by isolated teeth and jaws. The first docodontan known from decent remains was Haldanodon, from the Late Jurassic Guimarota site of Portugal. Recently, exceptionally preserved skeletons have been discovered in the Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation of China. Chinese docodontans include otter-like,[4] mole-like,[5] and squirrel-like species,[6][7] hinting at impressive ecological diversity within the group. Many docodontans have muscular limbs and broad tail vertebrae, adaptations for burrowing or swimming. Like true mammals, docodontans have hair,[4] a saddle-shaped hyoid apparatus,[7] and reduced postdentary jaw bones which are beginning to develop into middle ear ossicles. On the other hand, the postdentary bones are still attached to the jaw and skull, the nares (bony nostril rims) have yet to fuse, and in most species the spine's thoracic-lumbar transition is rather subdued.[5][6]

Description

[edit]Skeletal traits

[edit]Jaw and ear

[edit]Docodontans have a long and low mandible (lower jaw), formed primarily by the tooth-bearing dentary bone. The dentary connects to the cranium via a joint with the squamosal, a connection which is strengthened relative to earlier mammaliaforms. The other bones in the jaw, known as postdentary elements, are still connected to the dentary and lie within a groove (the postdentary trough) in the rear part of the dentary's inner edge. Nevertheless, they are very slender, hosting hooked prongs which start to converge towards an oval-shaped area immediately behind the dentary. The ectotympanic bone, also known as the angular, fits into a deep slot on the dentary which opens backwards, a characteristic unique to docodontans. The malleus (also known as the articular) sends down a particularly well-developed prong known as the manubrium, which is sensitive to vibrations. The incus (also known as the quadrate) is still relatively large and rests against the petrosal bone of the braincase, a remnant of a pre-mammalian style jaw joint. In true mammals, the postdentary elements detach fully and shrink further, becoming the ossicles of the middle ear and embracing a circular eardrum.[8][4][6][7]

Cranium and throat

[edit]Docodontan skulls are generally fairly low, and in general form are similar to other early mammaliforms such as morganucodonts. The snout is long and has several plesiomorphic traits: the nares (bony nostril holes) are small and paired, rather than fused into a single opening, and the rear edge of each naris is formed by a large septomaxilla, a bone which is no longer present in mammals. The nasal bones expand at the back and overlook thick lacrimals. The frontal and parietal bones of the skull roof are flat and broad, and there is no postorbital process forming the rear rim of the orbit (eye socket).[8][5][9]

Docodontans also see the first occurrence of a mammalian-style saddle-shaped complex of hyoids (throat bones). Microdocodon has a straight, sideways-oriented basihyal which connects to two pairs of bony structures: the anterior hyoid cornu (a jointed series of rods which snake up to the braincase), and the posterior thyrohyals (which link to the thyroid cartilage). This hyoid system affords greater strength and flexibility than the simple, U-shaped hyoids of earlier cynodonts. It allows for a narrower and more muscular throat and tongue, which are correlated with uniquely mammalian behaviors such as suckling.[7][10]

Postcranial skeleton

[edit]The oldest unambiguous fossil evidence of hair is found in a well-preserved specimen of the docodontan Castorocauda, though hair likely evolved much earlier in synapsids.[4] The structure of the vertebral column is variable between docodontans, as with many other mammaliaforms. The components of the atlas are unfused, attaching to the large and porous occipital condyles of the braincase.[11] Vertebrae at the base of the tail often have expanded transverse processes (rib pedestals), supporting powerful tail musculature.[4][6][11] Most docodontans have gradually shrinking ribs, forming a subdued transition between the thoracic and lumbar regions of the spine. However, this developmental trait is not universal. For example, Agilodocodon lacks lumbar ribs, so it has an abrupt transition from the thoracic to lumbar vertebrae like many modern mammals.[5][6]

The forelimbs and hindlimbs generally have strong muscle attachments, and the olecranon process of the ulna is flexed inwards.[12][5][11] All limb bones except the tibia lack epiphyses, plate-like ossified cartilage caps which terminate bone growth in adulthood. This suggests that docodontan bones continued growing throughout their lifetime, like some other mammaliaforms and early mammals.[12][11] The ankle is distinctive, with a downturned calcaneum and a stout astragalus which connects to the tibia via a trochlea (pulley-like joint).[5][6][7][11] The only known specimen of Castorocauda has a pointed spur on its ankle, similar to defensive structures observed in male monotremes and several other early-branching mammals.[4][13]

Teeth

[edit]Like other mammaliaforms, docodontan teeth include peg-like incisors, fang-like canines, and numerous interlocking premolars and molars. Most mammaliaforms have fairly simple molars primarily suited for shearing and slicing food. Docodontans, on the other hand, have developed specialized molars with crushing surfaces. The shape of each molar is defined by a characteristic pattern of conical cusps, with sharp, concave crests connecting the center of each cusp to adjacent cusps.[1]

Upper molars

[edit]

* Left side: right maxilla molar and left dentary molar in occlusal view (looking onto the teeth). Cusp nomenclature is labelled.

* Right side: left maxilla and dentary molars in lingual view (from the perspective of the tongue, right).

When seen from below, the upper molars have an overall subtriangular or figure-eight shape, wider (from side to side) than they are long (from front to back). The bulk of the tooth makes up four major cusps: cusps A, C, X, and Y. This overall structure is similar to the tribosphenic teeth found in true therian mammals, like modern marsupials and placentals. However, there is little consensus for homologizing docodontan cusps with those of modern mammals.[1]

Cusps A and C lie in a row along the labial edge of the tooth (i.e., on the outer side, facing the cheek). Cusp A is located in front of cusp C and is typically the largest cusp in the upper molars. Cusp X lies lingual to cusp A (i.e., positioned inwards, towards the midline of the skull). A distinct wear facet is found on the labial edge of cusp X, extending along the crest leading to cusp A. Cusp Y, a unique feature of docodontans, is positioned directly behind cusp X. Many docodontans have one or two additional cusps (cusps B and E) in front of cusp A. Cusp B is almost always present and is usually shifted slightly labial relative to cusp A. Cusp E, which may be absent in later docodontans, is positioned lingual to cusp B.[1]

Lower molars

[edit]The lower molars are longer than wide. On average, they have seven cusps arranged in two rows. The labial/outer row has the largest cusp, cusp a, which lies between two more cusps. The other major labial cusps are cusp b (a slightly smaller cusp in front of cusp a) and cusp d (a much smaller cusp behind cusp a). The lingual/inner row is shifted backwards (relative to the labial row) and has two large cusps: cusp g (at the front) and cusp c (at the back).[1]

Two additional lingual cusps may be present: cusp e and cusp df. Cusp e lies in front of cusp g and is roughly lingual to cusp b. Cusp df ("docodont cuspule f") lies behind cusp c and is lingual to cusp d. There is some variation in the relative sizes, position, or even presence of some of these cusps, though docodontans in general have a fairly consistent cusp pattern.[1]

Tooth occlusion

[edit]A distinct concavity or basin is apparent in the front half of each lower molar, between cusps a, g, and b. This basin has been named the pseudotalonid. When the upper and lower teeth occlude (fit together), the pseudotalonid acts as a receptacle for cusp Y of the upper molar. Cusp Y is often termed the "pseudoprotocone" in this relationship. At the same time, cusp b of the lower molar shears into an area labial to cusp Y. Occlusion is completed when the rest of the upper molar slides between adjacent lower molar teeth, letting the rear edge of the preceding lower molar scrape against cusp X. This shearing-and-grinding process is more specialized than in any other early mammaliaform.[1]

"Pseudotalonid" and "pseudoprotocone" are names which reference the talonid-and-protocone crushing complex which characterize tribosphenic teeth. Tribosphenic teeth show up in the oldest fossils of therians, the mammalian subgroup containing marsupials and placentals. This is a case of convergent evolution, as therian talonids lie at the back of the lower molar rather than the front. The opposite is true for docodontan teeth, which have been described as "pseudotribosphenic".[1]

Pseudotribosphenic teeth are also found in shuotheriids, an unusual collection of Jurassic mammals with tall pointed cusps. Relative to docodontans, shuotheriids have pseudotalonids which are positioned further forwards in their lower molars. This is potentially another case of convergent evolution, as shuotheriid are often considered true mammals related to modern monotremes.[3] Docodontan and shuotheriid teeth are so similar that some genera, namely Itatodon and Paritatodon, have been considered members of either group.[14][15] A 2024 study, describing the new shuotheriid Feredocodon, even proposed that shuotheriids and docodontans were most closely related to each other among mammaliaforms. The study named a new clade, Docodontiformes, to encompass the two groups.[2]

Paleoecology and paleobiology

[edit]-

Docofossor, a golden mole-like burrower

Docodontans and other Mesozoic mammals were traditionally thought to have been primarily ground dwelling and insectivorous, but recent more complete fossils from China have shown this is not the case.[16] Castorocauda[4] from the Middle Jurassic of China, and possibly Haldanodon[17][18] from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal, were specialised for a semi-aquatic lifestyle. Castorocauda had a flattened tail, similar to that of a beaver, and recurved molar cusps, which suggests a possible diet of fish or aquatic invertebrates.[4] It was thought possible that docodontans had tendencies towards semi-aquatic habits, given their presence in wetland environments,[19] although this could also be explained by the ease with which these environments preserve fossils compared with more terrestrial ones. Recent discoveries of other complete docodontans such as the specialised digging species Docofossor,[5] and specialised tree-dweller Agilodocodon[6] suggest Docodonta were more ecologically diverse than previously suspected. Docofossor shows many of the same physical traits as the modern day golden mole, such as wide, shortened digits in the hands for digging.[5]

Metabolism and lifespan

[edit]A 2024 study on adult and juvenile Krusatodon specimens found that docodontans had a slower metabolism and lower growth rates relative to modern mammals of the same size. The juvenile, which was 7 to 24 months old at the time of its death, was only 49% through the process of replacing its deciduous teeth with permanent (adult) teeth. Based on jaw length, the juvenile was 51-59% the weight of the 7-year-old adult. The closest comparisons among modern mammals were monotremes and hyraxes, though Krusatodon was much smaller than either, at fewer than 156 g in adult body mass. The authors propose that the standard condition in modern small mammals (very high metabolism, rapid growth, and short lifespan) would not be adopted until true mammals in the Jurassic mammals. In addition, docodontans contradict earlier assumptions that high metabolism evolved in sync with ecological diversity, since their diversity far outpaces their metabolism.[20]

Classification

[edit]The lineage of Docodonta evolved prior to the origin of living mammals: monotremes, marsupials, and placentals. In other words, docodontans are outside of the mammalian crown group, which only includes animals descended from the last common ancestor of living mammals. Previously, docodontans were sometimes regarded as belonging to Mammalia, owing to the complexity of their molars and the fact that they possess a dentary-squamosal jaw joint. However, modern authors usually limit the term "Mammalia" to the crown group, excluding earlier mammaliaforms like the docodontans. Nevertheless, docodontans are still closely related to crown-Mammalia, to a greater extent than many other early mammaliaform groups such as Morganucodonta and Sinoconodon. Some authors also consider docodontans to lie crownward of the order Haramiyida,[5] though most others consider haramiyidans to be closer to mammals than docodontans are.[4][21][7] Docodontans may lie crownward of haramiyidans in phylogenetic analyses based on maximum parsimony, but shift stemward relative to haramiyidans when the same data is put through a Bayesian analysis.[22]

Cladogram based on a phylogenetic analysis of Zhou et al. (2019) focusing on a wide range of mammaliamorphs:[7]

| Mammaliaformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Docodontan fossils have been recognized since the 1880s, but their relationships and diversity have only recently been well-established. Monographs by George Gaylord Simpson in the 1920s argued that they were specialized "pantotheres", part of a broad group ancestral to true therian mammals according to their complex molars.[23][24] A 1956 paper by Bryan Patterson instead argued that docodontan teeth were impossible to homologize with modern mammals. He drew comparisons to the teeth of Morganucodon and other "triconodont" mammaliaforms, which had fairly simple lower molars with a straight row of large cusps.[25] However, re-evaluations of mammaliaform tooth homology in the late 1990s established that docodontans were not closely related to either morganucodonts or therians.[26][27] Instead, they were found to be similar to certain early "symmetrodonts", a broad and polyphyletic grouping of mammaliaforms with triangular upper molars.[27]

The closest relatives of Docodonta may have been certain Late Triassic "symmetrodonts", such as Delsatia and Woutersia (from the Norian-Rhaetian of France).[1][28] These "symmetrodonts" have three major cusps (c, a, and b) set in a triangular arrangement on their lower molars. These cusps would be homologous to cusps c, a, and g in docodontans, which have a similar size and position. The lingual cusp (cusp X) is prominent in Woutersia.[1] Another proposed docodontan relative, Tikitherium from India, was originally considered to have been a very early mammaliaform which lived during the Carnian stage of the Triassic. Later investigation found that Tikitherium was likely a misidentification of Neogene shrew teeth, completely unrelated to docodontans or any Mesozoic mammaliaforms.[29]

Unambiguous docodontans are restricted to the Northern Hemisphere. The oldest docodontan is Nujalikodon, from the earliest Jurassic (Hettangian stage) of Greenland.[30] Many more species appear in the fossil record in the Middle Jurassic. Very few docodontans survived into the Cretaceous Period; the youngest known members of the group are Sibirotherium and Khorotherium, from the Early Cretaceous of Siberia.[31][32] One disputed docodont, Gondtherium, has been described from India, which was previously part of the Southern Hemisphere continent of Gondwana.[33][1] However, this identification is not certain, and in recent analyses, Gondtherium falls outside the docodontan family tree, albeit as a close relative to the group.[6][7] Reigitherium, from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina, has previously been described as a docodont,[34] though it is now considered a meridiolestidan mammal.[35] Some authors have suggested splitting Docodonta into two families (Simpsonodontidae and Tegotheriidae),[36][14][37] but the monophyly of these groups (in their widest form) are not found in any other analyses, and therefore not accepted by all mammal palaeontologists.[38]

Cladograms based on phylogenetic analyses focusing on docodontan relationships:

| Topology of Zhou et al. (2019), based on tooth, cranial, and postcranial traits:[7] | Topology of Panciroli et al. (2021), based on dentary and tooth traits:[9]

|

Species

[edit]- Agilodocodon scansorius Meng et al. 2015[6]

- Borealestes Waldman & Savage 1972

- B. cuillinensis Panciroli et al. 2021[9]

- B. serendipitus Waldman & Savage 1972[39]

- Castorocauda lutrasimilis Ji et al. 2006[4]

- Cyrtlatherium canei Freeman 1979 sensu Sigogneau-Russell 2001 (dubious) [Simpsonodon oxfordensis Kermack et al. 1987]

- Dobunnodon mussettae [Borealestes mussetti] Sigogneau-Russell 2003 sensu Panciroli et al. 2021[9]

- Docodon Marsh 1881 [Dicrocynodon Marsh in Osborn, 1888; Diplocynodon Marsh 1880 non Pomel 1847; Ennacodon Marsh 1890; Enneodon Marsh 1887 non Prangner 1845]

- D. apoxys Rougier et al. 2014

- D. hercynicus Martin et al. 2024[40]

- D. victor (Marsh 1880) [Dicrocynodon victor (Marsh 1880); Diplocynodon victor Marsh 1880]

- D. striatus Marsh 1881 [disputed]

- D. affinis (Marsh 1887) [Enneodon affinis Marsh 1887] [disputed]

- D. crassus (Marsh 1887) [Enneodon crassus Marsh 1887; Ennacodon crassus (Marsh 1887)] [disputed]

- D. superus Simpson 1929 [disputed]

- Docofossor brachydactylus Luo et al. 2015[5]

- Dsungarodon zuoi Pfretzschner et al. 2005 [Acuodulodon Hu, Meng & Clark 2007; Acuodulodon sunae Hu, Meng & Clark 2007]

- Ergetiis ichchi Averianov et al. 2024[41]

- Gondtherium dattai Prasad & Manhas 2007[33] [disputed]

- Haldanodon exspectatus Kühne & Krusat 1972 sensu Sigoneau-Russell 2003[17]

- Hutegotherium yaomingi Averianov et al. 2010[37]

- Itatodon tatarinovi Lopatin & Averianov 2005 [disputed, possibly a shuotheriid][15]

- Khorotherium yakutensis Averianov et al. 2018[31]

- Krusatodon kirtlingtonensis Sigogneau-Russell 2003

- Microdocodon gracilis Zhou et al. 2019[7]

- Nujalikodon cassiopeiae Patrocínio et al. 2025[30]

- Paritatodon kermacki (Sigogneau-Russell, 1998) [disputed, possibly a shuotheriid][15]

- Peraiocynodon Simpson 1928

- P. inexpectatus Simpson 1928 [possible synonym of Docodon][42]

- P. major Sigogneau-Russell 2003 [disputed]

- Sibirotherium rossicus Maschenko, Lopatin & Voronkevich 2002

- Simpsonodon Kermack et al. 1987

- S. splendens (Kühne 1969)

- S. sibiricus Averianov et al. 2010

- Tashkumyrodon desideratus Martin & Averianov 2004

- Tegotherium gubini Tatarinov 1994

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Luo, Zhe-Xi; Martin, Thomas (2007). "Analysis of Molar Structure and Phylogeny of Docodont Genera". Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. 2007 (39): 27–47. doi:10.2992/0145-9058(2007)39[27:AOMSAP]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0145-9058. S2CID 29846648.

- ^ a b Mao, Fangyuan; Li, Zhiyu; Wang, Zhili; Zhang, Chi; Rich, Thomas; Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Meng, Jin (2024-04-03). "Jurassic shuotheriids show earliest dental diversification of mammaliaforms". Nature. 628 (8008): 569–575. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07258-7. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ a b Martin, Thomas; Jäger, Kai R. K.; Plogschties, Thorsten; Schwermann, Achim H.; Brinkkötter, Janka J.; Schultz, Julia A. (2020). "Molar diversity and functional adaptations in Mesozoic mammals" (PDF). In Martin, Thomas; von Koenigswald, Wighart (eds.). Mammalian Teeth - Form and Function. München, Germany: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 187–214.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ji, Qiang; Luo, Zhe-Xi; Yuan, Chong-Xi; Tabrum, Alan R. (2006-02-24). "A Swimming Mammaliaform from the Middle Jurassic and Ecomorphological Diversification of Early Mammals". Science. 311 (5764): 1123–1127. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1123J. doi:10.1126/science.1123026. PMID 16497926. S2CID 46067702.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Luo, Zhe-Xi; Meng, Qing-Jin; Ji, Qiang; Liu, Di; Zhang, Yu-Guang; Neander, April I. (2015-02-13). "Evolutionary development in basal mammaliaforms as revealed by a docodontan". Science. 347 (6223): 760–764. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..760L. doi:10.1126/science.1260880. PMID 25678660. S2CID 206562572.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Meng, Qing-Jin; Ji, Qiang; Zhang, Yu-Guang; Liu, Di; Grossnickle, David M.; Luo, Zhe-Xi (2015-02-13). "An arboreal docodont from the Jurassic and mammaliaform ecological diversification". Science. 347 (6223): 764–768. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..764M. doi:10.1126/science.1260879. PMID 25678661. S2CID 206562565.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Zhou, Chang-Fu; Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan; Neander, April; Martin, Thomas; Luo, Zhe-Xi (19 Jul 2019). "New Jurassic mammaliaform sheds light on early evolution of mammal-like hyoid bones". Science. 365 (6450): 276–279. Bibcode:2019Sci...365..276Z. doi:10.1126/science.aau9345. PMID 31320539. S2CID 197663503.

- ^ a b Lillegraven, Jason A.; Krusat, Georg (1991-10-01). "Cranio-mandibular anatomy of Haldanodon exspectatus (Docodonta; Mammalia) from the late Jurassic of Portugal and its implications to the evolution of mammalian characters". Rocky Mountain Geology. 28 (2): 39–138. ISSN 1555-7332.

- ^ a b c d Panciroli, Elsa; Benson, Roger B J; Fernandez, Vincent; Butler, Richard J; Fraser, Nicholas C; Luo, Zhe-Xi; Walsh, Stig (2021-07-30). "New species of mammaliaform and the cranium of Borealestes (Mammaliformes: Docodonta) from the Middle Jurassic of the British Isles". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 192 (4): 1323–1362. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa144. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Hoffmann, Simone; Krause, David W. (2019-07-19). "Tongues untied". Science. 365 (6450): 222–223. Bibcode:2019Sci...365..222H. doi:10.1126/science.aay2061. PMID 31320523. S2CID 197663377.

- ^ a b c d e Panciroli, Elsa; Benson, Roger B. J.; Fernandez, Vincent; Humpage, Matthew; Martín-Serra, Alberto; Walsh, Stig; Luo, Zhe-Xi; Fraser, Nicholas C. (2021). "Postcrania of Borealestes (Mammaliformes, Docodonta) and the emergence of ecomorphological diversity in early mammals". Palaeontology. 65. doi:10.1111/pala.12577. ISSN 1475-4983. S2CID 244822141.

- ^ a b Martin, Thomas (2005-10-01). "Postcranial anatomy of Haldanodon exspectatus (Mammalia, Docodonta) from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) of Portugal and its bearing for mammalian evolution". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 145 (2): 219–248. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00187.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Hurum, J.H.; Luo, Z-X; Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. (2006). "Were mammals originally venomous?" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (1): 1–11.

- ^ a b Averianov, A. O.; Lopatin, A. V. (December 2006). "Itatodon tatarinovi (Tegotheriidae, Mammalia), a docodont from the Middle Jurassic of Western Siberia and phylogenetic analysis of Docodonta". Paleontological Journal. 40 (6): 668–677. Bibcode:2006PalJ...40..668A. doi:10.1134/s0031030106060098. ISSN 0031-0301. S2CID 129438779.

- ^ a b c Wang, Yuan-Qing; Li, Chuan-Kui (2016). "Reconsideration of the systematic position of the Middle Jurassic mammaliaforms Itatodon and Paritatodon" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica. 67: 249–256. doi:10.4202/pp.2016.67_249 (inactive 12 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Luo, Zhe-Xi (2007). "Transformation and diversification in early mammal evolution". Nature. 450 (7172): 1011–1019. Bibcode:2007Natur.450.1011L. doi:10.1038/nature06277. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 18075580. S2CID 4317817.

- ^ a b Kühne W. G. and Krusat, G. 1972. Legalisierung des Taxon Haldanodon (Mammalia, Docodonta). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie Monatshefte 1972:300-302

- ^ Krusat, G. 1991 Functional morphology of Haldanodon exspectatus (Mammalia, Docodonta) from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal. Fifth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota.

- ^ Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: Bulletin 36

- ^ Panciroli, Elsa; Benson, Roger B. J.; Fernandez, Vincent; Fraser, Nicholas C.; Humpage, Matt; Luo, Zhe-Xi; Newham, Elis; Walsh, Stig (2024). "Jurassic fossil juvenile reveals prolonged life history in early mammals". Nature. 632 (8026): 815–822. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07733-1. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Luo, Zhe-Xi; Gatesy, Stephen M.; Jenkins, Farish A.; Amaral, William W.; Shubin, Neil H. (2015-12-22). "Mandibular and dental characteristics of Late Triassic mammaliaform Haramiyavia and their ramifications for basal mammal evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (51): E7101 – E7109. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E7101L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1519387112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4697399. PMID 26630008.

- ^ Luo, Zhe-Xi; Meng, Qing-Jin; Grossnickle, David M.; Liu, Di; Neander, April I.; Zhang, Yu-Guang; Ji, Qiang (2017). "New evidence for mammaliaform ear evolution and feeding adaptation in a Jurassic ecosystem". Nature. 548 (7667): 326–329. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..326L. doi:10.1038/nature23483. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 28792934. S2CID 4463476.

- ^ Simpson, George Gaylord (1928). "A Catalogue of the Mesozoic Mammalia in the Geological Department of the British Museum". Trustees of the British Museum, London: 1–215.

- ^ Simpson, George Gaylord (1929). "American Mesozoic Mammalia". Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Yale University. 3 (1): 1–235.

- ^ Patterson, Bryan (1956). "Early Cretaceous mammals and the evolution of mammalian molar teeth". Fieldiana. 13 (1): 1–105.

- ^ Sigogneu-Russell, Denise; Hahn, Renate (1995). "Reassessment of the late Triassic symmetrodont mammal Woutersia" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 40 (3): 245–260.

- ^ a b Butler, P. M. (1997-06-19). "An alternative hypothesis on the origin of docodont molar teeth". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (2): 435–439. Bibcode:1997JVPal..17..435B. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10010988. ISSN 0272-4634. JSTOR 4523820.

- ^ Abdala, Fernando; Gaetano, Leandro C. (2018), Tanner, Lawrence H. (ed.), "The Late Triassic Record of Cynodonts: Time of Innovations in the Mammalian Lineage", The Late Triassic World: Earth in a Time of Transition, Topics in Geobiology, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 407–445, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-68009-5_11, ISBN 978-3-319-68009-5

- ^ Averianov, Alexander O.; Voyta, Leonid L. (2024-02-28). "Putative Triassic stem mammal Tikitherium copei is a Neogene shrew". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 31 (1): 10. doi:10.1007/s10914-024-09703-w. ISSN 1573-7055.

- ^ a b Patrocínio, Sofia; Panciroli, Elsa; Rotatori, Filippo Maria; Mateus, Octavio; Milàn, Jesper; Clemmensen, Lars B.; Crespo, Vicente D. (2025). "The oldest definitive docodontan from central East Greenland sheds light on the origin of the clade". Papers in Palaeontology. 11 (3) e70022. doi:10.1002/spp2.70022. ISSN 2056-2802.

- ^ a b Alexander Averianov; Thomas Martin; Alexey Lopatin; Pavel Skutschas; Rico Schellhorn; Petr Kolosov; Dmitry Vitenko (2018). "A high-latitude fauna of mid-Mesozoic mammals from Yakutia, Russia". PLoS ONE. 13 (7): e0199983. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0199983.

- ^ Lopatin, A. V.; Averianov, A. O.; Kuzmin, I. T.; Boitsova, E. A.; Saburov, P. G.; Ivantsov, S. V.; Skutschas, P. P. (2020). "A New Finding of a Docodontan (Mammaliaformes, Docodonta) in the Lower Cretaceous of Western Siberia". Doklady Earth Sciences. 494 (1): 667–669. Bibcode:2020DokES.494..667L. doi:10.1134/S1028334X20090123. ISSN 1028-334X. S2CID 224811982.

- ^ a b Prasad GVR, and Manhas BK. 2007. A new docodont mammal from the Jurassic Kota Formation of India. Palaeontologia electronica, 10.2: 1-11.

- ^ Pascual, Rosendo; Goin, Francisco J.; Gonzalez, Pablo; Ardolino, Alberto; Puerta, Pablo F. (2000). "A highly derived docodont from the Patagonian Late Cretaceous: evolutionary implications for Gondwanan mammals". Geodiversitas. 22 (3): 395–414.

- ^ Harper, Tony; Parras, Ana; Rougier, Guillermo W. (2019-12-01). "Reigitherium (Meridiolestida, Mesungulatoidea) an Enigmatic Late Cretaceous Mammal from Patagonia, Argentina: Morphology, Affinities, and Dental Evolution". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 26 (4): 447–478. doi:10.1007/s10914-018-9437-x. hdl:11336/81478. ISSN 1573-7055. S2CID 21654055.

- ^ L. P. Tatarinov (1994). "On an unusual mammalian tooth from the Mongolian Jurassic". Journal of the Geological Society of London. 128: 119–125.

- ^ a b Averianov, A. A.; Lopatin, A. V.; Krasnolutskii, S. A.; Ivantsov, S. V. (2010). "New docodontians from the Middle Jurassic of Siberia and reanalysis of docodonta interrelationships" (PDF). Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS. 314 (2): 121–148. doi:10.31610/trudyzin/2010.314.2.121. S2CID 35820076.

- ^ Panciroli, Elsa; Benson, Roger B. J.; Luo, Zhe-Xi (2019-05-04). "The mandible and dentition of Borealestes serendipitus (Docodonta) from the Middle Jurassic of Skye, Scotland". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 39 (3) e1621884. Bibcode:2019JVPal..39E1884P. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1621884. hdl:20.500.11820/75714386-2baa-4512-b4c8-add5719f129b. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 199637122.

- ^ Waldman, M and Savage, R.J.G 1972 The first Jurassic mammal from Scotland. Journal of the Geological Society of London 128:119-125

- ^ Martin, T.; Averianov, A. O.; Lang, A. J.; Schultz, J. A.; Wings, O. (2024). "Docodontans (Mammaliaformes) from the Late Jurassic of Germany". Historical Biology. 37 (2): 255–263. doi:10.1080/08912963.2023.2300635. S2CID 267167016.

- ^ Averianov, A. O.; Martin, T.; Lopatin, A. V.; Skutschas, P. P.; Vitenko, D. D.; Schellhorn, R.; Kolosov, P. N. (2024). "Docodontans from the Lower Cretaceous of Yakutia, Russia: new insights into diversity, morphology, and phylogeny of Docodonta". Cretaceous Research. 158 105836. Bibcode:2024CrRes.15805836A. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2024.105836. S2CID 267164151.

- ^ Butler PM. 1939. The teeth of the Jurassic mammals. In Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 109:329-356). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

External links

[edit]Docodonta

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and general characteristics

Docodonta is an order of extinct Mesozoic mammaliaforms, representing advanced cynodonts that are closely related to but positioned outside the crown-group Mammalia.[4] These animals were among the earliest diverging lineages of mammaliaforms, characterized by a suite of traits that highlight their transitional position in mammalian evolution. Docodontans exhibited small, rodent-like body plans, with lengths typically ranging from 5 to 50 cm and estimated body masses between 10 and 800 grams, though most known species fell within the smaller end of this spectrum. For instance, the genus Docodon measured about 10 cm in length and weighed around 30 grams, while the semi-aquatic Castorocauda reached up to 50 cm and 500–800 grams. A defining feature of docodontans was their pseudotribosphenic dentition, which featured complex molar occlusions adapted for grinding and shearing, distinct from the tribosphenic pattern seen in later mammals.[4] This dental specialization supported varied diets and contributed to their ecological diversity. Evidence for fur is preserved in fossils such as Castorocauda, indicating that docodontans possessed hair, a key mammalian trait for thermoregulation, predating similar evidence in crown mammals. Additionally, their jaw apparatus showed transitional characteristics, with reduced postdentary elements beginning to detach and function as middle ear ossicles, bridging reptilian and mammalian auditory systems.[5] The temporal range of Docodonta spans from the Early Jurassic (Hettangian stage) to the Early Cretaceous, though the clade was most diverse and abundant during the Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous.[4][6] This longevity underscores their success as one of the dominant non-mammalian mammaliaform groups during the Mesozoic. Docodontans displayed diverse ecomorphologies, including semi-aquatic and possibly arboreal adaptations in some forms.Evolutionary significance

Docodonta represents one of the earliest diverging clades of mammaliaforms, positioned as a stem group that bridges non-mammalian cynodonts and crown-group mammals, offering critical insights into the transition to true mammalian characteristics.[7][8] As advanced cynodonts from the Early Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous, docodontans exhibit a mosaic of primitive and derived traits, including a functional quadrate-articular jaw joint alongside emerging mammalian features, which highlights the gradual evolution of the mammalian skull and auditory system.[9] A key innovation in Docodonta is the early development of complex dental occlusion, characterized by rectangular lower molars and hourglass-shaped uppers with prominent crests and crenelations that enabled precise shearing for diverse feeding strategies, such as processing tough or pliable plant and animal matter.[10] This shearing mechanism, distinct from the crushing-focused tribospheny of therians, prefigures the expansion of occlusal surfaces and transverse shear seen in later mammals, demonstrating an independent evolutionary experiment in dental complexity during the Jurassic radiation of mammaliaforms.[10] Docodonta provides direct evidence for mammalian origins through preserved soft tissue indicators, including fur impressions in genera like Castorocauda, suggesting insulation for elevated activity levels, and a specialized hyoid apparatus in forms like Microdocodon gracilis from the Jurassic of China, which supported muscularized suckling and swallowing—precursors to lactation in crown mammals.[11] These features, combined with locomotor adaptations implying sustained metabolic demands, point to endothermy precursors that facilitated ecological diversification among early mammaliaforms.[12] Recent discoveries, such as Nujalikodon cassiopeiae from the Early Jurassic of Greenland, confirm the clade's early origin around 201–199 Ma and rapid diversification.[4] Historically, Docodonta was first described based on Docodon specimens from the Morrison Formation, initially named under the preoccupied Diplocynodon in 1877 and formally established by Marsh in 1880, with early workers like Simpson (1929) viewing their specialized dentition as too derived for direct ancestry to therians.[13] Initial misconceptions arose from superficial dental resemblances to multituberculates, leading some to group them closely, but detailed jaw and occlusion studies clarified their distinct lineage by the mid-20th century.[14] Recent phylogenetic analyses, such as the 2024 study incorporating Feredocodon, reinforce Docodonta's basal position among mammaliaforms while refining interclade relationships.[15]Fossil record

Temporal and geographic distribution

Docodonta first appeared during the Late Triassic, with potential early representatives such as Delsatia rhupotopi from the Autunian (Rhaetian) deposits of Saint-Nicolas-de-Port, France, dated to approximately 201 million years ago (Ma).[1] However, definitive members of the clade are known from the Early Jurassic, including Nujalikodon cassiopeiae from the Rhætelv Formation in central East Greenland, which dates to the Hettangian stage at around 199 Ma.[1] This specimen represents the oldest unambiguous docodontan and highlights an early diversification phase shortly after the Triassic-Jurassic boundary.[1] The group achieved its peak diversity during the Middle to Late Jurassic, spanning the Bathonian to Tithonian stages (approximately 168–145 Ma), with abundant fossils documented across northern continents.[1] Records from this interval are particularly rich in Europe (e.g., the United Kingdom), North America (e.g., the Morrison Formation in the United States), and Asia (e.g., the Yanliao Biota in northeastern China, including the Tiaojishan Formation, which has yielded exceptionally preserved specimens).[1] Docodonta persisted into the Early Cretaceous, with the latest confirmed occurrences in the Barremian stage (approximately 125–129 Ma) from high-paleolatitude sites in Asia, such as the Teete locality in Yakutia, Russia, where they formed a significant portion of the mammalian assemblage. A more recent and controversial extension of the temporal range comes from Patagonia, Argentina, where Reigitherium bunodontum from the La Colonia Formation (Campanian-Maastrichtian, approximately 72 Ma) was initially interpreted as a highly derived docodont based on dental features like crenulated crowns.[16] Subsequent analyses have reclassified it within Meridiolestida.[17] Geographically, Docodonta exhibited a predominantly Laurasian distribution, with fossils concentrated in what are now Europe, North America, and Asia, reflecting their adaptation to a range of terrestrial environments across the supercontinent.[1] Rare southern hemisphere extensions include the Greenland find and the disputed Patagonian record, suggesting limited dispersal to Gondwanan margins.[1][17] Their presence at high paleolatitudes, such as in Siberian and Greenlandic deposits, indicates tolerance for cooler climatic conditions during periods of global variability.Notable discoveries and specimens

One of the earliest notable discoveries of docodonts was the initial specimen of Docodon from the Morrison Formation in Wyoming, United States, described in 1877 under the preoccupied name Diplocynodon before formal naming in 1880.[18] This find, consisting primarily of dental remains, established Docodon as a key representative of the group in North American Late Jurassic deposits and highlighted their relative abundance in fluvial environments.[18] Exceptionally preserved skeletons from the Middle to Late Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation in China have revolutionized insights into docodont ecomorphology and soft tissue anatomy. The 2006 discovery of Castorocauda lutrasimilis yielded a near-complete skeleton with preserved fur, a flattened tail, and barbels, indicating semi-aquatic adaptations and pushing back evidence of such lifestyles in mammaliaforms by over 100 million years. In 2015, Agilodocodon scansorius was described from articulated remains showing elongated limbs, curved claws, and dental features for an omnivorous, sap-feeding diet, marking the earliest evidence of arboreal locomotion in the group. That same year, Docofossor brachydactylus was identified from a skeleton with robust forelimbs, reduced phalanges, and shovel-like claws, revealing fossorial specializations and genetic parallels to modern subterranean mammals. These Tiaojishan specimens underscore the rapid ecological diversification of docodonts during the Jurassic. Recent discoveries have filled critical evolutionary gaps in docodont origins and distribution. In 2025, Nujalikodon cassiopeiae was described from a partial jaw and teeth in the Early Jurassic Rhætelv Formation of Greenland, dated to approximately 199 million years ago, representing the oldest definitive docodont and extending the group's record back by about 40 million years while indicating high-latitude presence.[1] Dsungarodon zuoi, initially described in 2005 from isolated teeth in the Late Jurassic Qigu Formation of China and reanalyzed in 2010, demonstrated advanced occlusal complexity and contributed to understanding Asian docodont radiation.[19][20] The disputed Reigitherium bunodontum from the Late Cretaceous La Colonia Formation in Patagonia, Argentina, with new specimens analyzed in 2011, showed bunodont dentition adapted for crushing and, though reclassified as a meridiolestidan, indicated similarities to docodonts beyond the Jurassic.[21] Preservation quality in these specimens has enabled detailed studies of ontogeny and soft tissues. Castorocauda notably preserves fur and sensory structures, offering direct evidence of integument in early mammaliaforms. In 2024, a growth series of Krusatodon kirtlingtonensis from the Middle Jurassic of the Isle of Skye, United Kingdom, including a juvenile and adult skeleton, revealed prolonged postnatal development with slower growth rates and longer lifespans compared to modern small mammals, informed by dental cementum analysis.[22]Anatomy

Cranial and dental features

The cranium of docodontans is characterized by a low, elongated structure with a long, gracile rostrum that constitutes a significant portion of the overall skull length, as seen in Borealestes serendipitus from the Middle Jurassic of Scotland.[23] The skull typically exhibits a triangular outline in dorsal and ventral views, widest at the level of the squamosal, with broad, flat frontal and parietal bones forming the roof and a small sagittal crest on the parietals.[23] Paired external nares are positioned anteriorly, with a wide anterior nasal notch terminating just anterior to the nasal foramina, and the nasals extend broadly posteriorly toward the base of the zygomatic arch.[23] The jaw articulation in docodontans features a mammalian-like dentary-squamosal joint that functions as the primary hinge, supplemented by a secondary articulation involving postdentary elements.[14] These postdentary bones, including the angular, articular, prearticular, and surangular, are slender and lie within a postdentary trough on the medial side of the dentary, representing remnants of Meckel's cartilage that are in the process of detaching to form middle ear ossicles such as the malleus and incus.[14] In the ear region, the petrosal bone is highly vascularized with prominent trans-cochlear sinuses and a curved cochlear canal, as evidenced in Borealestes, where a bony ridge separates the fenestra vestibuli from the prootic canal and facial foramen.[24] The stapes exhibits a bullate morphology with parallel crura and a nearly circular footplate, similar to that in Haldanodon.[24] The hyoid apparatus in docodontans adopts a mammalian configuration, consisting of a basihyal, paired ceratohyals, epihyals, and thyrohyals that form a mobile, saddle-shaped structure enabling enhanced tongue mobility and suckling capabilities, as preserved in Microdocodon gracilis from the Middle Jurassic of China.[11] Docodontan dentition is heterodont, comprising procumbent incisors, a prominent canine, multiple premolars, and specialized molars arranged in upper and lower tooth rows.[25] The molars display a pseudotribosphenic pattern: upper molars are subtriangular with principal cusps A and C buccally, X and Y lingually (Y smaller and distal), and a distal pseudotrigon basin bordered by crests A-X mesially and C-Y distally, facilitating crushing via the pseudoprotocone-like cusp X.[25] Lower molars are rectangular with 7-8 cusps arranged in rows, including main buccal cusps a and b, lingual cusps e, g, c, and df, and a mesial pseudotalonid basin that opens mesio-lingually, bordered by crests a-b buccally and a-g distally.[25] Some docodontans exhibit diphyodonty with multiple replacement sets for anterior teeth, though posterior molars are typically monophyodont.[25] Occlusion in docodontans involves a cyclic, mediolateral power stroke with buccal-to-lingual shearing and grinding motions, where the lower cusp b crushes into the upper pseudotrigon basin and cusp Y grinds into the lower pseudotalonid basin during phase 1, followed by proal upward shearing in phase 1b and palinal downward grinding in phase 2.[25] Wear facets on cusps, such as lingual surfaces of A and C (up to 0.36 mm²), document these mechanics, with buccal grooves on lower molars guiding occlusion along upper cusps.[25]Postcranial skeleton

The postcranial skeleton of docodontans exhibits a mosaic of primitive and derived features, reflecting their position as early mammaliaforms with emerging locomotor diversity. The vertebral column typically comprises 7 cervical vertebrae, 12–15 thoracic vertebrae, 5–6 lumbar vertebrae, and variable sacral fusion, with an elongated tail in some taxa consisting of up to 25 caudal vertebrae.[26] For example, in Castorocauda lutrasimilis, the column includes an estimated 14 thoracic, 7 lumbar, and 3 sacral vertebrae, with caudal vertebrae 5–13 dorsoventrally compressed and bearing bifurcate transverse processes that support a broad, beaver-like tail for swimming.[26] In Borealestes serendipitus, preserved elements include 2 cervical and 3 thoracic vertebrae with amphicoelous centra and long neural spines, alongside 4 caudal vertebrae indicating a sturdy, mobile tail.[2] Sacral vertebrae show variable fusion across docodontans, contributing to pelvic stability in different habits.[2] The ribs are double-headed, a retained cynodont trait, with broad costal plates in proximal thoracolumbar ribs that overlap for structural support; up to 9 ribs are preserved in B. serendipitus, lacking the flattened form seen in aquatic C. lutrasimilis.[26][2] The pectoral girdle retains a non-mammalian coracoid fused to the scapula, as in Borealestes and Haldanodon, with a mammalian-like scapula featuring a narrower glenoid fossa; the pelvic girdle includes an ilium intermediate in development between basal and derived forms.[2] Limbs are generally strong, with fore- and hindlimbs showing variable robusticity adapted to diverse activities. The humerus bears an entepicondylar foramen, a plesiomorphic cynodont feature for nerve passage, and displays flared deltopectoral crests; in B. cuillinensis, it measures 10.4 mm long and is robust, intermediate between slender climbers and diggers.[2] Forelimbs in fossorial taxa like Docofossor brachydactylus and H. exspectatus are stout and short, with hypertrophied epicondyles and expanded distal joints for powerful digging.[27] In contrast, Agilodocodon scansorius has more gracile, elongated limbs suited for climbing, while C. lutrasimilis features robust forelimbs for digging and rowing, with a wide distal humerus, block-like carpals, and webbed hind digits indicated by soft tissue remnants.[28][26] Some taxa, including C. lutrasimilis, possess ankle spurs reminiscent of those in monotremes, potentially associated with venom delivery.[26] Evidence of integument includes fur and scutes preserved in fossils. C. lutrasimilis shows carbonized guard hairs and underfur across the body, with a scaly tail proximally covered by hairs transitioning to sparse scales distally.[26] No such soft tissues are preserved in Borealestes, but terminal phalanges suggest unspecialized claws.[2]Taxonomy

Phylogenetic relationships

Docodonta occupies a basal position within Mammaliaformes as stem-mammaliaforms, outside the crown-group Mammalia comprising Monotremata and Theria. Phylogenetic analyses consistently place Docodonta more derived than early mammaliaforms such as morganucodontans but basal to eutriconodonts and other advanced clades, supported by shared primitive features like the dentary-squamosal jaw joint and petrosal promontorium while lacking crown synapomorphies such as true tribosphenic molars. Some studies propose Docodonta as sister to Allotheria (encompassing multituberculates and haramiyidans), forming a non-therian clade characterized by complex multicuspidate dentition, whereas others position it more stemward, basal to the Monotremata + Theria divergence, with minimal tree-length differences indicating unresolved ambiguity (e.g., 0.6% variation in parsimony scores).[29] A 2024 cladistic analysis incorporating new shuotheriid material reclassifies shuotheriids within Docodontiformes, expanding the clade to include these taxa alongside traditional docodontans based on shared pseudotribosphenic dental features, such as a pseudotalonid anterior to the trigonid and rearranged cusp patterns enabling precise occlusion. This revision challenges prior separations of shuotheriids as ausktribosphenids and highlights early dental diversification in Mammaliaformes. Complementing this, Bayesian phylogenetic analyses recover two major subclades within Docodonta: one comprising Haldanodon + (Docodon + Docofossor), characterized by Euroamerican affinities and specific molar wear facets, and a second encompassing remaining docodontans with broader Laurasian distributions and varying cusp morphologies.[30][1] Debates persist regarding potential affinities with symmetrodonts, as basal docodontans exhibit "symmetrodont-like" molar arrangements with transversely aligned cusps, suggesting close relations to Late Triassic forms such as Delsatia and Woutersia, though these links rely on contested cusp homologies and lack unambiguous synapomorphies. Docodonta's exclusion from crown Mammalia stems from its pseudotribosphenic dentition, which simulates but does not equate to the true tribospheny of therians via independent evolutionary convergence in occlusion mechanics. Autapomorphic support for Docodonta includes advanced dental complexity with multiple longitudinal crests for grinding and diverse postcranial adaptations reflecting varied locomotor ecologies, distinguishing it from outgroups like morganucodontans.[29]Families and genera

Docodonta encompasses approximately 12 to 14 recognized genera across its Mesozoic record, with around 30 valid species described to date, though taxonomic revisions continue to refine synonymies and placements.[31][32] Notable synonymies include Cyrtlatherium as a synonym of Simpsonodon (based on deciduous dentition) and Peraiocynodon potentially synonymous with Docodon due to overlapping dental morphology in Purbeck-Morrison equivalents.[33] Diversity peaks in the Jurassic of Asia, with multiple genera reflecting adaptive radiations, while European and North American records dominate the Middle to Late Jurassic.[31] The order is traditionally divided into several families, though phylogenetic analyses sometimes recover paraphyletic arrangements or alternative groupings, such as Simpsonodontidae and Tegotheriidae as sister clades.[34]| Family | Key Genera and Notes |

|---|---|

| Docodontidae | Docodon (6 species, e.g., D. victor, Late Jurassic, North America; complex molars for omnivory); Haldanodon (e.g., H. exspectatus, Late Jurassic, Portugal; well-preserved postcrania indicating terrestrial habits). Borealestes often treated as a stem docodontid.[34][33] |

| Simpsonodontidae | Borealestes (e.g., B. serendipitus, Middle Jurassic, Europe; multiple species including B. cuillinensis); Simpsonodon (e.g., S. oxfordensis, S. sibiricus, Middle Jurassic, Europe/Asia); Dsungarodon (Late Jurassic, China). Characterized by derived lower molar crests.[34][33] |

| Tegotheriidae | Tegotherium (Late Triassic-Early Jurassic, Europe); Delsatia (Early Jurassic, Europe); Krusatodon (e.g., K. kirtlingtonensis, Middle Jurassic, Europe); Sibirotherium, Hutegotherium (Middle Jurassic, Asia); Itatodon (basal, Middle Jurassic, Siberia). Features include reduced cusp rows and Asiatic endemism in some taxa.[34][31] |