Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Area of a triangle

View on Wikipedia

In geometry, calculating the area of a triangle is an elementary problem encountered often in many different situations. The best known and simplest formula is where b is the length of the base of the triangle, and h is the height or altitude of the triangle. The term "base" denotes any side, and "height" denotes the length of a perpendicular from the vertex opposite the base onto the line containing the base. Euclid proved that the area of a triangle is half that of a parallelogram with the same base and height in his book Elements in 300 BCE.[1] In 499 CE Aryabhata, used this illustrated method in the Aryabhatiya (section 2.6).[2]

Although simple, this formula is only useful if the height can be readily found, which is not always the case. For example, the land surveyor of a triangular field might find it relatively easy to measure the length of each side, but relatively difficult to construct a 'height'. Various methods may be used in practice, depending on what is known about the triangle. Other frequently used formulas for the area of a triangle use trigonometry, side lengths (Heron's formula), vectors, coordinates, line integrals, Pick's theorem, or other properties.[3]

History

[edit]Heron of Alexandria found what is known as Heron's formula for the area of a triangle in terms of its sides, and a proof can be found in his book, Metrica, written around 60 CE. It has been suggested that Archimedes knew the formula over two centuries earlier,[4] and since Metrica is a collection of the mathematical knowledge available in the ancient world, it is possible that the formula predates the reference given in that work.[5] In 300 BCE Greek mathematician Euclid proved that the area of a triangle is half that of a parallelogram with the same base and height in his book Elements of Geometry.[6]

In 499 Aryabhata, a great mathematician-astronomer from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy, expressed the area of a triangle as one-half the base times the height in the Aryabhatiya.[7]

A formula equivalent to Heron's was discovered by the Chinese independently of the Greeks. It was published in 1247 in Shushu Jiuzhang ("Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections"), written by Qin Jiushao.[8]

Using trigonometry

[edit]

The area of a triangle can be found through the application of trigonometry.

Knowing SAS (side-angle-side)

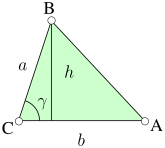

[edit]Using the labels in the image on the right, the height or altitude is . Substituting this in the area formula derived above, the area of the triangle can be expressed as:

Where is the line BC, is the line AC, is the line AB, is the interior angle at A, is the interior angle at B, is the interior angle at C.

Furthermore, since , and similarly for the other two angles:

Knowing AAS (angle-angle-side)

[edit]Since , and similarly for the other two angles:

and analogously if the known side is or .

Knowing ASA (angle-side-angle)

[edit]and analogously if the known side is or .[9]

Using side lengths (Heron's formula)

[edit]A triangle's shape is uniquely determined by the lengths of the sides, so its metrical properties, including area, can be described in terms of those lengths. By Heron's formula,

where is the semiperimeter, or half of the triangle's perimeter.

Three other equivalent ways of writing Heron's formula are

Formulas resembling Heron's formula

[edit]Three formulas have the same structure as Heron's formula but are expressed in terms of different variables. First, denoting the medians from sides , , and respectively as , , and and their semi-sum , we have[10]

Next, denoting the altitudes from sides , , and respectively as , , and , and denoting the semi-sum of the reciprocals of the altitudes as we have[11]

And denoting the semi-sum of the angles' sines as , we have[12]

where is the diameter of the circumcircle:

Using vectors

[edit]The area of triangle ABC is half of the area of a parallelogram:

where , , and are vectors to the triangle's vertices from any arbitrary origin point, so that and are the translation vectors from vertex to each of the others, and is the wedge product. If vertex is taken to be the origin, this simplifies to .

The oriented relative area of a parallelogram in any affine space, a type of bivector, is defined as where and are translation vectors from one vertex of the parallelogram to each of the two adjacent vertices. In Euclidean space, the magnitude of this bivector is a well-defined scalar number representing the area of the parallelogram. (For vectors in three-dimensional space, the bivector-valued wedge product has the same magnitude as the vector-valued cross product, but unlike the cross product, which is only defined in three-dimensional Euclidean space, the wedge product is well-defined in an affine space of any dimension.)

The area of triangle ABC can also be expressed in terms of dot products. Taking vertex to be the origin and calling translation vectors to the other vertices and ,

where for any Euclidean vector .[13] This area formula can be derived from the previous one using the elementary vector identity .

In two-dimensional Euclidean space, for a vector with coordinates and vector with coordinates , the magnitude of the wedge product is

(See the following section.)

Using coordinates

[edit]If vertex A is located at the origin (0, 0) of a Cartesian coordinate system and the coordinates of the other two vertices are given by B = (xB, yB) and C = (xC, yC), then the area can be computed as 1⁄2 times the absolute value of the determinant

For three general vertices, the equation is:

which can be written as

If the points are labeled sequentially in the counterclockwise direction, the above determinant expressions are positive and the absolute value signs can be omitted.[14] The above formula is known as the shoelace formula or the surveyor's formula.

If we locate the vertices in the complex plane and denote them in counterclockwise sequence as a = xA + yAi, b = xB + yBi, and c = xC + yCi, and denote their complex conjugates as , , and , then the formula

is equivalent to the shoelace formula.

In three dimensions, the area of a general triangle A = (xA, yA, zA), B = (xB, yB, zB) and C = (xC, yC, zC) is the Pythagorean sum of the areas of the respective projections on the three principal planes (i.e. x = 0, y = 0 and z = 0):

Using line integrals

[edit]The area within any closed curve, such as a triangle, is given by the line integral around the curve of the algebraic or signed distance of a point on the curve from an arbitrary oriented straight line L. Points to the right of L as oriented are taken to be at negative distance from L, while the weight for the integral is taken to be the component of arc length parallel to L rather than arc length itself.

This method is well suited to computation of the area of an arbitrary polygon. Taking L to be the x-axis, the line integral between consecutive vertices (xi,yi) and (xi+1,yi+1) is given by the base times the mean height, namely (xi+1 − xi)(yi + yi+1)/2. The sign of the area is an overall indicator of the direction of traversal, with negative area indicating counterclockwise traversal. The area of a triangle then falls out as the case of a polygon with three sides.

While the line integral method has in common with other coordinate-based methods the arbitrary choice of a coordinate system, unlike the others it makes no arbitrary choice of vertex of the triangle as origin or of side as base. Furthermore, the choice of coordinate system defined by L commits to only two degrees of freedom rather than the usual three, since the weight is a local distance (e.g. xi+1 − xi in the above) whence the method does not require choosing an axis normal to L.

When working in polar coordinates it is not necessary to convert to Cartesian coordinates to use line integration, since the line integral between consecutive vertices (ri,θi) and (ri+1,θi+1) of a polygon is given directly by riri+1sin(θi+1 − θi)/2. This is valid for all values of θ, with some decrease in numerical accuracy when |θ| is many orders of magnitude greater than π. With this formulation negative area indicates clockwise traversal, which should be kept in mind when mixing polar and cartesian coordinates. Just as the choice of y-axis (x = 0) is immaterial for line integration in cartesian coordinates, so is the choice of zero heading (θ = 0) immaterial here.

Using Pick's theorem

[edit]See Pick's theorem for a technique for finding the area of any arbitrary lattice polygon (one drawn on a grid with vertically and horizontally adjacent lattice points at equal distances, and with vertices on lattice points).

The theorem states:

where is the number of internal lattice points and B is the number of lattice points lying on the border of the polygon.

Other area formulas

[edit]Numerous other area formulas exist, such as

where r is the inradius, and s is the semiperimeter (in fact, this formula holds for all tangential polygons), and[15]: Lemma 2

where are the radii of the excircles tangent to sides a, b, c respectively.

We also have

and[16]

for circumdiameter D; and[17]

for angle α ≠ 90°.

The area can also be expressed as[18]

In 1885, Baker[19] gave a collection of over a hundred distinct area formulas for the triangle. These include:

for circumradius (radius of the circumcircle) R, and

Upper bound on the area

[edit]The area T of any triangle with perimeter p satisfies

with equality holding if and only if the triangle is equilateral.[20][21]: 657

Other upper bounds on the area T are given by[22]: p.290

and

both again holding if and only if the triangle is equilateral.

Bisecting the area

[edit]There are infinitely many lines that bisect the area of a triangle.[23] Three of them are the medians, which are the only area bisectors that go through the centroid. Three other area bisectors are parallel to the triangle's sides.

Any line through a triangle that splits both the triangle's area and its perimeter in half goes through the triangle's incenter. There can be one, two, or three of these for any given triangle.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Euclid's Proof of the Pythagorean Theorem | Synaptic". Central College. Retrieved 2023-07-12.

- ^ The Āryabhaṭīya by Āryabhaṭa (translated into English by Walter Eugene Clark, 1930) hosted online by the Internet Archive.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Triangle area". MathWorld.

- ^ Heath, Thomas L. (1921). A History of Greek Mathematics (Vol II). Oxford University Press. pp. 321–323.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Heron's Formula". MathWorld.

- ^ "Euclid's Proof of the Pythagorean Theorem | Synaptic". Central College. Retrieved 2023-07-12.

- ^ Clark, Walter Eugene (1930). The Aryabhatiya of Aryabhata: An Ancient Indian Work on Mathematics and Astronomy (PDF). University of Chicago Press. p. 26.

- ^ Xu, Wenwen; Yu, Ning (May 2013). "Bridge Named After the Mathematician Who Discovered the Chinese Remainder Theorem" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 60 (5): 596–597. doi:10.1090/noti993.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Triangle". MathWorld.

- ^ Benyi, Arpad, "A Heron-type formula for the triangle," Mathematical Gazette 87, July 2003, 324–326.

- ^ Mitchell, Douglas W., "A Heron-type formula for the reciprocal area of a triangle," Mathematical Gazette 89, November 2005, 494.

- ^ Mitchell, Douglas W., "A Heron-type area formula in terms of sines," Mathematical Gazette 93, March 2009, 108–109.

- ^ The quantity represents geometric product of a vector with itself.

- ^ Bart Braden (1986). "The Surveyor's Area Formula" (PDF). The College Mathematics Journal. 17 (4): 326–337. doi:10.2307/2686282. JSTOR 2686282. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2003. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ "Sa ́ndor Nagydobai Kiss, "A Distance Property of the Feuerbach Point and Its Extension", Forum Geometricorum 16, 2016, 283–290" (PDF).

- ^ "Circumradius". AoPSWiki. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Mitchell, Douglas W., "The area of a quadrilateral," Mathematical Gazette 93, July 2009, 306–309.

- ^ Pathan, Alex, and Tony Collyer, "Area properties of triangles revisited," Mathematical Gazette 89, November 2005, 495–497.

- ^ Baker, Marcus, "A collection of formulae for the area of a plane triangle," Annals of Mathematics, part 1 in vol. 1(6), January 1885, 134–138; part 2 in vol. 2(1), September 1885, 11–18. The formulas given here are #9, #39a, #39b, #42, and #49. The reader is advised that several of the formulas in this source are not correct.

- ^ Chakerian, G.D. "A Distorted View of Geometry." Ch. 7 in Mathematical Plums (R. Honsberger, editor). Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, 1979: 147.

- ^ Rosenberg, Steven; Spillane, Michael; and Wulf, Daniel B. "Heron triangles and moduli spaces", Mathematics Teacher 101, May 2008, 656–663.

- ^ Posamentier, Alfred S., and Lehmann, Ingmar, The Secrets of Triangles, Prometheus Books, 2012.

- ^ Dunn, J.A., and Pretty, J.E., "Halving a triangle," Mathematical Gazette 56, May 1972, 105–108.

Area of a triangle

View on GrokipediaFundamental Formulas

Base and Height

The area of a triangle is given by the formula , where is the length of the base (any chosen side) and is the height, defined as the perpendicular distance from the opposite vertex to the line containing the base.[7] This formula holds regardless of the triangle's orientation, as the height can be measured externally if the triangle is obtuse.[8] One intuitive derivation arises from comparing the triangle to a parallelogram. By reflecting the triangle over one of its sides, two congruent triangles form a parallelogram with the same base and height ; since the parallelogram's area is , the triangle's area is half of that, or .[9][8] Alternatively, using rectangular coordinates, place the base along the x-axis from to and the third vertex at ; the area is then half the absolute value of the determinant formed by the coordinates, which simplifies to .[10] For a right triangle with legs of lengths and , the area is simply , as the legs serve directly as base and height.[7] In an obtuse triangle, the height to the chosen base may fall outside the triangle, extending beyond one endpoint, yet the formula remains applicable by using the perpendicular distance.[8] Diagrams illustrating the altitude to various bases—such as an acute triangle with internal height or an obtuse one with external height—clarify these measurements visually.[6] The resulting area is expressed in square units, consistent with the units of base and height (e.g., square meters if both are in meters), ensuring dimensional homogeneity.[11] This base-height approach provides the foundational geometric intuition for area, extendable to trigonometric forms when heights are not directly perpendicular.[12]Equivalent Geometric Forms

The area of a triangle can be expressed in terms of the lengths of its three medians , , and , which connect each vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side. The formula is where is the semiperimeter of the medians.[13] This provides a symmetric alternative to the base-height formula, relying solely on internal segment lengths that intersect at the centroid. A brief derivation using vector geometry proceeds as follows. Let the position vectors of the vertices be , , and , with the centroid . The median from to the midpoint of BC has length , and similarly for the others. The vectors from the centroid to the vertices satisfy . The area is three times the area of the triangle formed by , , and , given by . Expressing the side lengths in terms of the medians via (and cyclic permutations), derived from the vector differences, and substituting into the vector cross-product area formula yields the median-based expression after simplification.[13] For example, consider a scalene triangle with medians , , . Then , and This computes the area without direct measurement of sides or heights.[13] Another equivalent form involves the inradius , the radius of the incircle tangent to all three sides, and the semiperimeter : This follows from dividing the triangle into three smaller triangles from the incenter (the intersection of the angle bisectors) to each side. Each smaller triangle has height and bases , , , so the total area is .[14] The medians intersect at the centroid, which divides the triangle into three smaller triangles of equal area, each with area . In an equilateral triangle with side length , the centroid coincides with other centers, and the area simplifies to This can be generalized using barycentric coordinates, where the centroid has coordinates , and the area ratios are determined by the coordinate sums relative to the vertices.[15] The altitudes , , (perpendicular distances from vertices to opposite sides) also yield an equivalent relation. Since , it follows that , and thus the product is This connects the altitudes directly to the area and side lengths.Trigonometric Formulas

Side-Angle-Side (SAS)

The side-angle-side (SAS) configuration for a triangle specifies two sides, denoted as and , and the included angle between them. The area of such a triangle is given by the formula where is the sine of the included angle.[16] This formula arises directly from the standard base-height approach to triangle area, adapted using trigonometry.[17] To derive this, consider side as the base. Drop a perpendicular from the opposite vertex to this base, forming height . In the right triangle created by this altitude, , since is the ratio of the opposite side to the hypotenuse in that right triangle. Substituting into the base-height formula yields . This derivation holds regardless of whether angle is acute or obtuse, as the height is always taken positively.[17][3] Unlike the ambiguous side-side-angle (SSA) case, the SAS configuration uniquely determines the triangle up to congruence, ensuring a single possible area value without multiple solutions. This follows from the SAS congruence postulate, which states that two triangles with two corresponding sides and the included angle equal are congruent.[18][19] For example, in an isosceles triangle with equal sides units and vertex angle , the area is square units. The same computation in radians uses radians, where , yielding the identical result. These examples assume standard units like meters for sides, producing area in square meters; computational tools often require specifying degrees or radians for the angle input to evaluate accurately.[16] Since triangle angles range from to less than , is always non-negative in this context, so the absolute value is unnecessary for ensuring a positive area, though it emphasizes the formula's robustness. Precision in computation depends on the accuracy of angle measurement and sine evaluation, typically to several decimal places in practical applications.[3] This SAS formula found early application in surveying, where trigonometric calculations of triangle areas facilitated mapping large terrains; for instance, it supported the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India starting in 1802, enabling precise area determinations over vast regions using measured sides and angles from triangulation networks.[20]Angle-Side-Angle (ASA) and Angle-Angle-Side (AAS)

In the Angle-Side-Angle (ASA) case, two angles and the included side of a triangle are known, which uniquely determines the triangle up to congruence.[21] To compute the area, first determine the third angle using the fact that the sum of angles in a triangle is 180 degrees; for angles and with included side (between vertices with angles and ), the third angle is .[22] Next, apply the law of sines to find one of the adjacent sides, such as side opposite angle : , so .[23] With sides and now known and the included angle between them, the area is given by the SAS formula: . Substituting the expression for yields the direct ASA formula .[21] This direct formula can be derived more elegantly by combining the law of sines with the general area expression involving the circumradius . From the law of sines, , , and .[23] The area of any triangle is also .[22] Substituting the expressions for the sides gives . Since , solve for and substitute: , confirming the formula.[21] An equivalent form is , which follows from trigonometric identities since .[21] This ASA configuration often arises in problems involving angle bisectors, where the bisector divides an angle into two equal parts, allowing the resulting smaller triangles to be analyzed using ASA to compute their areas. For example, if a triangle has angles , , and included side , then , and the area is .[21] In the Angle-Angle-Side (AAS) case, two angles and a non-included side (opposite one of the angles) are known, which also uniquely determines the triangle. The computation proceeds similarly: find the third angle , then use the law of sines to determine another side, such as side opposite when side (opposite ) is given: , so .[23] The sides and enclose angle , so the area is via the SAS formula. Substituting for gives the direct AAS formula . Unlike the SSA case, AAS always yields a unique triangle with no ambiguity. The AAS formula derives analogously from the circumradius approach. Using and the law of sines substitutions, . With , , substitution yields . For illustration, consider angles , , and side opposite ; then , and the area is . In practice, ensure angle units are consistent (degrees or radians) across trigonometric functions to avoid errors, and prefer the direct formulas over intermediate side computations when possible for numerical stability, as they reduce rounding accumulation.[22]Formulas from Side Lengths

Heron's Formula

Heron's formula provides the area of a triangle solely in terms of its three side lengths , , and . Named after Hero of Alexandria, who described it in his work Metrica around 60 CE, the formula states that the area is given by where is the semiperimeter.[24] This expression enables computation of the area without requiring heights, angles, or coordinates, making it valuable when only side lengths are known. One common derivation begins with the law of cosines to express an angle in terms of the sides, followed by the side-angle-side (SAS) area formula. Applying the law of cosines, , and substituting into the SAS formula yields , leading after algebraic simplification to the Heron's form.[25] An alternative proof places the triangle in the coordinate plane for direct computation via the determinant formula for area. Position vertex B at , vertex C at , and vertex A at . The side lengths give the equations , , and the base BC = . Solving for eliminates and results in , which simplifies to the squared Heron's expression.[26] Heron's formula can also be viewed as a special case of Brahmagupta's formula for the area of a cyclic quadrilateral, where one side length approaches zero, reducing the quadrilateral to a triangle.[27] For a scalene triangle with sides 3, 4, and 5, the semiperimeter , so , confirming the known right-triangle area. However, for near-collinear "skinny" triangles, such as sides 1, 1, and where , the terms and become nearly equal to , causing subtractive cancellation in floating-point arithmetic and loss of precision in the product under the square root.[28] The formula relates to the inradius of the triangle via , where the area equals the inradius times the semiperimeter, as the incircle's tangents divide the perimeter into equal segments.[29] Generalizations extend Heron's approach to higher dimensions, such as formulas for the volume of a tetrahedron in terms of its edge lengths, using similar algebraic structures but without deriving the full expression here.[30]Cayley-Menger Determinant

The Cayley-Menger determinant provides a coordinate-free method to compute the area of a triangle using only its side lengths, expressed through the determinant of a symmetric matrix constructed from the squared distances between the vertices. For a triangle with vertices labeled 1, 2, 3 and side lengths , , , the squared area is given by where the matrix is bordered by a row and column of 1's along the off-diagonal positions corresponding to an auxiliary dimension.[31] This formula arises as a special case of the general Cayley-Menger determinant for the content (volume) of simplices in higher dimensions, here applied to a 2-simplex embedded in Euclidean space. The derivation of this expression begins with the coordinate representation of the triangle's area using the determinant formula for three points in the plane: . By expressing the squared distances and forming the Gram matrix of dot products , the area relates to via after centering the coordinates (subtracting the centroid). Row and column operations on an augmented matrix transform this into the bordered form of the Cayley-Menger matrix, yielding the determinant relation above; this process embeds the 2D configuration as a degenerate 3D simplex with zero volume, linking to the general formula for simplex content.[32] Alternatively, it can be viewed as projecting the volume formula for a 3D tetrahedron onto the plane, where the auxiliary point enforces flatness.[33] This determinant-based approach offers advantages in distance geometry and computational applications, as it avoids explicit coordinate assignments and directly handles metric information, facilitating tasks like rigidity analysis and embedding verification in Euclidean space.[33] It is particularly useful in computational geometry for solving geometric constraints without solving systems of equations for positions, enabling efficient numerical checks for realizability of distance sets.[34] Historically, the determinant was first introduced by Arthur Cayley in 1841 to establish conditions for points to lie in a lower-dimensional subspace, such as coplanarity, using algebraic invariants of distance matrices; this laid the foundation for volume computations from edge lengths in polyhedra. Karl Menger extended and formalized it in 1928 for general simplices, solidifying its role in modern geometry.[33] For an equilateral triangle with side length , the formula yields the known area , confirming equivalence to the standard formula.[31] This matrix form serves as a simplified special case of Heron's formula when expanded.[31] In practice, the determinant can be computed using linear algebra libraries, such as MATLAB'sdet function or Python's NumPy linalg.det, for numerical verification in software implementations.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}T&={\tfrac {1}{4}}{\sqrt {(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2})^{2}-2(a^{4}+b^{4}+c^{4})}}\\[5mu]&={\tfrac {1}{4}}{\sqrt {2(a^{2}b^{2}+a^{2}c^{2}+b^{2}c^{2})-(a^{4}+b^{4}+c^{4})}}\\[5mu]&={\tfrac {1}{4}}{\sqrt {(a+b+c)(-a+b+c)(a-b+c)(a+b-c)}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c7908427a23cfbb7110e9ca5f689262353516099)

![{\displaystyle T={\tfrac {1}{2}}{\sqrt[{3}]{abch_{a}h_{b}h_{c}}},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2ea7f73597047c74387004a689ccbd3d244624d0)