Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

USB hardware

View on Wikipedia

- Micro-B plug

- Proprietary UC-E6 connector used on many older Japanese cameras for both USB and analog AV output

- Mini-B plug (inverted)

- Standard-A receptacle (inverted; non-compliant because USB does not allow extension cables[1])

- Standard-A plug

- Standard-B plug

The initial versions of the USB standard specified connectors that were easy to use and that would have high life spans; revisions of the standard added smaller connectors useful for compact portable devices. Higher-speed development of the USB standard gave rise to another family of connectors to permit additional data links. All versions of USB specify cable properties. Version 3.x cables, marketed as SuperSpeed, added a data link; namely, in 2008, USB 3.0 added a full-duplex lane (two twisted pairs of wires for one differential signal of serial data per direction), and in 2014, the USB-C specification added a second full-duplex lane.

USB has always included some capability of providing power to peripheral devices, but the amount of power that can be provided has increased over time. The modern specifications are called USB Power Delivery (USB-PD) and allow up to 240 watts. Initially USB 1.0/2.0 provided up to 2.5 W, USB 3.0 provided up to 4.5 W, and subsequent Battery Charging (BC) specifications provided power up to 7.5 W. The modern Power Delivery specifications began with USB PD 1.0 in 2012, providing for power delivery up to 60 watts; PD 2.0 version 1.2 in 2013, along with USB 3.1, up to 100 W; and USB PD 3.1 in 2021 raised the maximum to 240 W. USB has been selected as the charging format for many mobile phones and other peripherial devices and hubs, reducing the proliferation of proprietary chargers. Since USB 3.1 USB-PD is part of the USB standard. The latest PD versions can easily also provide power to laptops.

A standard USB-C cable is specified for 60 watts and at least of USB 2.0 data capability.

In 2019, USB4, now exclusively based on USB-C, added connection-oriented video and audio interfacing abilities (DisplayPort) and compatibility to Thunderbolt 3+.

Connectors

[edit]

Unlike other data buses (such as Ethernet), USB connections are directed; a host device has downstream-facing ports (DFP) that connect to the upstream-facing port (UFP) of hubs or peripheral devices. USB implements a tiered star-like network topology.

Only downstream-facing ports originally provided power by default; this topology was chosen to easily prevent electrical overloads and damaged equipment.

Every legacy USB cable has two distinct ends with mechanically distinct plugs, one Type-A plug (connecting to a downstream-facing port of a host or hub) and one Type-B plug (connecting to the upstream-facing port of a hub or peripheral device). Each format has a plug and receptacle defined for each of the A and B ends. A USB cable, by definition, has a plug on each end. With one exception (Type-A to Type-A plugs) every cable had one Type-A plug and one Type-B plug. With the release of Type‑C came transitional cables: a Type‑C plug at one end and a Type-A or a Type-B plug at the other. These transitional cables are still directional, and in such a cable the Type‑C plug is electrically marked as either A or B as appropriate to complement the opposite connector. The modern standard is a cable with a Type-C plug on each end; these cables are non-directional, leaving it to the connected devices to negotiate their respective roles. All legacy receptacles are either Type-A or Type-B except the Micro‑AB and (deprecated) Mini‑AB receptacles. Such an Type-AB receptacle accepts both Type-A and Type-B plugs, and a device with such a receptacle takes the DFP (host, hub DFP) or UFP (peripheral device, hub UFP) role according to the type of plug attached.

There are three sizes of legacy USB connectors: The original Standard, the Mini connectors, which were the first attempt to accommodate handheld mobile equipment (now mostly deprecated), and Micro, all of which were superseded in 2014 by Type‑C, which is required for operation modes with two lanes (USB 3.2 1×2 (10 Gbit/s), USB 3.2 2×2 (20 Gbit/s), or any USB4 modes) and allows power up to 240 watts in either direction.

Before USB4, there are five speeds for USB data transfer: Low-Speed, Full-Speed (both USB 1.0 and 1.1), High-Speed (USB 2.0), SuperSpeed (USB 3.0, later designated as USB 3.2 Gen 1×1), and SuperSpeed+ (designated as USB 3.1 Gen 2, later as USB 3.2 Gen 2×1).

Legacy connectors have differing hardware and cabling requirements for the first three generations of the standard (USB 1.x, USB 2.0, and USB 3.x). USB devices have some choice of implemented modes, and since USB 3.1 the USB release alone does not sufficiently designate implemented modes. Which capabilities a device supports are defined by the device's chipset or included SoC and the OS's supported drivers (therefore one must check the full names of the supported USB operation modes in the device's specification; the printed icons usually do not specify all modes, or precisely enough). In the USB 3 specifications it is recommended that the insulators visible inside Standard‑A SuperSpeed plugs and receptacles be a specific blue color (Pantone 300 C).[2] In Standard‑A receptacles with support for the 10 Gbit/s (Gen 2) signaling rate introduced in USB 3.1, some makers instead use a teal blue color, but the standards recommend the same blue for all SuperSpeed-capable Standard‑A receptacles, including those capable of the higher rate.

Properties

[edit]

The connectors the USB committee specifies support a number of USB's underlying goals, and reflect lessons learned from the many connectors the computer industry has used. The connector mounted on the host or device is called the receptacle, and the connector attached to the cable is called the plug.[3] The USB specification documents also periodically define the term male to represent the plug, and female to represent the receptacle.[4][clarification needed]

By design, it is difficult to insert a USB plug into its receptacle incorrectly. The USB specification requires that the cable plug and receptacle be marked so the user can recognize the proper orientation.[3] The USB‑C plug, however, is reversible. USB cables and small USB devices are held in place by the gripping force from the receptacle, with no screws, clips, or thumb-turns as other connectors use.

The different A and B plugs prevent accidentally connecting two power sources. However, some of this directed topology is lost with the advent of multi-purpose USB connections (such as USB On-The-Go in smartphones, and USB-powered Wi-Fi routers), which require A-to-A, B-to-B, and sometimes Y/splitter cables. See the USB On-The-Go connectors section below for a more detailed summary description.

There are so-called cables with A plugs on both ends, which may be valid if the "cable" includes, for example, a USB host-to-host transfer device with two ports.[5] This is, by definition, a device with two logical B ports, each with a captive cable, not a cable with two A ends.

Durability

[edit]The standard connectors were designed to be more robust than many past connectors. This is because USB is hot-swappable, and the connectors would be used more frequently, and perhaps with less care, than previous connectors.

Standard USB connectors have a minimum rated lifetime of 1,500 cycles of insertion and removal,[6] and this increased to 5,000 cycles for Mini-B connectors.[6] The rating for all Micro connectors is 10,000 cycles,[6] and the same applies to USB-C.[7] To accomplish this, a locking device was added and a leaf spring was moved from the jack to the plug, so that the most-stressed part is on the cable side of the connection. This change was made so that the connector on the less expensive cable would bear the most wear.[6][page needed]

In standard USB, the electrical contacts in a USB connector are protected by an adjacent plastic tongue, and the entire connecting assembly is usually protected by an enclosing metal shell.[6]

The shell on the plug makes contact with the receptacle before any of the internal pins. The shell is typically grounded, to dissipate static electricity and to shield the wires within the connector.

Compatibility

[edit]The USB standards specify dimensions and tolerances for connectors, to prevent physical incompatibilities, including maximum dimensions of plug bodies and minimum clear spaces around receptacles so that adjacent ports are not blocked.

Pin assignments

[edit]USB 1.0, 1.1, and 2.0 use two wires for power (VBUS and GND) and two wires for one differential signal of serial data.[8] Mini and Micro connectors five contacts each, rather than the four of Standard connectors, with the additional contact, designated ID, electrically differentiating A and B plugs when connecting to the AB receptacles of On-The-Go devices.[9] The Type‑C plug of a Type‑C-to-legacy cable or adapter is similarly electronically marked as A or B: In a cable, it is marked as the complement of the connector on the opposite end because every legacy cable by definition has an A and a B end, and in an adapter the Type‑C plug is marked to match the plug the adapter accepts.

USB 3.0 added a (bi-directional) lane (two additional differential pairs with a total of four wires, SSTx+, SSTx−, SSRx+ and SSRx−), providing full-duplex data transfers at SuperSpeed, making it similar to Serial ATA or single-lane PCI Express.

- Power (VBUS, 5 V)

- Data− (D−)

- Data+ (D+)

- ID (On-The-Go)

- GND

- SuperSpeed transmit− (SSTx−)

- SuperSpeed transmit+ (SSTx+)

- GND

- SuperSpeed receive− (SSRx−)

- SuperSpeed receive+ (SSRx+)

| Pin | Name | Wire color[a] | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VBUS | Red or | Orange | +5 V |

| 2 | D− | White or | Gold | Data− |

| 3 | D+ | Green | Data+ | |

| 4 | GND | Black or | Blue | Ground |

| Pin | Name | Wire color[a] | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VBUS | Red | +5 V |

| 2 | D− | White | Data− |

| 3 | D+ | Green | Data+ |

| 4 | ID | None (only used in plug) | When a cable is connected to a Mini- or Micro-AB receptacle, the ID pin indicates to the On-The-Go device whether the plug is the Type-A (host) or Type-B (peripheral device) end of its cable, causing the device to behave as a host or peripheral accordingly.

|

| 5 | GND | Black | Signal ground |

Colors

[edit]

| Color | Location | Description | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (required by USB standards)[11][citation needed] |

Receptacles and plugs | Micro‑A, Mini‑A | ||||||

| Black (required by USB standards)[11][4] |

Receptacles and plugs | Micro‑B, Mini‑B | ||||||

| Grey (required by USB standards)[11][citation needed] |

Receptacles | Micro‑AB, Mini‑AB | ||||||

| Blue (Pantone 300 C) (recommended in USB standards)[2] |

Receptacles and plugs | Indicates a Standard‑A connector supports USB 5Gbps (introduced in USB 3.0), and possibly 10Gbps (introduced in USB 3.1) | ||||||

| Teal blue (not part of USB standards) |

Receptacles and plugs | Indicates a Standard‑A or Standard‑B connector supports USB SuperSpeed(+) 10Gbps (introduced in USB 3.1) | ||||||

| Green (not part of USB standards) |

Receptacles and plugs | Type‑A or Type‑B, Qualcomm Quick Charge (QC) | ||||||

| Purple (not part of USB standards) |

Plugs only | Type‑A or Type‑C, Huawei SuperCharge | ||||||

| Yellow or red (not part of USB standards) |

Receptacles only | High-current or sleep-and-charge | ||||||

| Orange (not part of USB standards) |

Receptacles only | High-retention connector, mostly used on industrial hardware | ||||||

USB ports and connectors are often color-coded to distinguish their different capabilities and modes. Color coding is only required for the insulators visible inside Micro and Mini connectors: A connectors are white, B black, and AB receptacles, which accept both A and B plugs, grey. Pantone 300 C is recommended for USB 3 Standard‑A connectors, including those with 10Gbps capability, though some manufacturers instead use nonstandard teal for receptacles capable of USB 10Gbps.[2]: §5.3.1.4 [3]: §5.3.1.3

Types

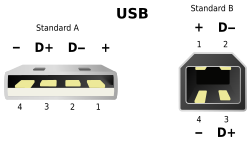

[edit]USB connector types multiplied as the specification progressed. The original USB specification detailed Standard-A and Standard-B plugs and receptacles, then referred to as simply Type‑A and Type‑B, then as other Type‑A and Type‑B connectors were added (first Mini, then Micro), the terms Standard‑A and Standard‑B were applied to the original connectors. The A–B distinction is to enforce the directional architecture of USB, with only the host and hubs having Type‑A receptacles and each peripheral device having a Type‑B. The data pins in the standard plugs are recessed compared to the power pins so that power and grounding is established before the data conductors are connected, and the reverse when unplugging. Some devices operate in different modes depending on whether the data connection is made. Charging docks supply power and do not include a host device or data pins, allowing any capable USB device to charge or operate from a standard USB cable. Charging cables provide power connections but not data. In a charge-only cable, the data wires are shorted at the device end; otherwise, the device may reject the charger as unsuitable.

Standard connectors

[edit]

- Standard‑A connectors: This plug has an elongated rectangular cross-section, inserts into a Standard‑A receptacle on a downstream facing port (DFP) on a USB host or hub, and carries both power and data.[12][13]

- Standard‑B connectors: This plug has a near square cross-section with the top exterior corners beveled. As part of a removable cable, it inserts into a single upstream facing port (UFP) on a device, such as a printer. On some devices, the Standard‑B receptacle has no data connections, being used solely for accepting power from the upstream device. This two-connector-type scheme (A–B) prevents a user from accidentally creating a loop.[14][15]

The maximum allowed cross-section of the overmold boot (which is part of the connector used for its handling) is 16 by 8 mm (0.63 by 0.31 in) for the Standard-A plug type, while for the Standard‑B it is 11.5 by 10.5 mm (0.45 by 0.41 in).[4]

Mini connectors

[edit]

Mini-USB connectors were introduced together with USB 2.0 in April 2000, mostly used with smaller devices such as digital cameras, smartphones, and tablet computers. Both Mini-A and Mini-B plugs are approximately 3 by 7 mm (0.12 by 0.28 in).

The Mini-A connectors and the Mini-AB receptacle were deprecated in May 2007, meaning their use in new products has been prohibited since then.[16] The more common Mini-B connectors are still permitted, but they are not On-The-Go–compliant and cannot be certified;[17][18][19] the Mini-B connector was common for transferring data to and from early smartphones and PDAs, and it appears on devices including the PlayStation Portable and the Motorola Razr V3, where it also acts as a charger on the latter.

The Mini-AB receptacle accepts either the Mini-A or the Mini-B plug, causing the On-The-Go device to behave as a host (A) or peripheral (B) accordingly.

Micro connectors

[edit]Micro-USB connectors, which were announced by the USB-IF on January 4, 2007,[20][21] have a similar width to Mini-USB but approximately half the thickness, enabling their integration into thinner portable devices. The Micro-A plug is 6.85 by 1.80 mm (0.270 by 0.071 in) with a maximum plug body size of 11.7 by 8.5 mm (0.46 by 0.33 in), while the Micro-B plug has the same height and width with a slightly smaller maximum plug body size of 10.6 by 8.5 mm (0.42 by 0.33 in).[10]

The thinner Micro-USB connectors were intended to replace the Mini connectors in devices manufactured from May 2007 through late 2014, including smartphones, personal digital assistants, and cameras.[22]

The Micro plug design is rated for at least 10,000 connect–disconnect cycles, which is more than the Mini plug design.[20][23] The Micro connector is also designed to reduce the mechanical wear on the device; instead, the easier-to-replace cable is designed to bear more of the mechanical wear of connection and disconnection. The Universal Serial Bus Micro-USB Cables and Connectors Specification details the mechanical characteristics of Micro-A plugs, Micro-AB receptacles (which accept both Micro-A and Micro-B plugs), and Micro-B plugs and receptacles,[23] along with a permitted adapter with a Standard-A receptacle and a Micro-A plug, as would be used e.g. to connect a camera to an existing Standard-A–B cable attached to a desktop printer.

Despite the introduction of the USB-C plug (see below), the Micro-B plug continues to be fitted on certain, often budget, hardware.[24]

OMTP standard

[edit]Micro-USB was endorsed as the standard connector for data and power on mobile devices by the cellular phone carrier group Open Mobile Terminal Platform (OMTP) in 2007.[25]

Micro-USB was embraced as the "Universal Charging Solution" by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in October 2009.[26]

In Europe, micro-USB became the defined common external power supply (EPS) for use with smartphones sold in the EU,[27] and 14 of the world's largest mobile phone manufacturers signed the EU's common EPS Memorandum of Understanding (MoU).[28][29] Apple, one of the original MoU signers, makes Micro-USB adapters available—as permitted in the Common EPS MoU—for its iPhones equipped with Apple's proprietary 30-pin dock connector and, later, Lightning connector.[30][31] according to the CEN, CENELEC, and ETSI.

USB 3.x connectors and backward compatibility

[edit]

USB 3.0 introduced SuperSpeed plugs and receptacles, both Standard and Micro. All 3.0 SuperSpeed receptacles (Standard-A, Standard-B, Micro-B, and Micro-AB) are backward-compatible with the corresponding pre-3.0 plugs; additionally, the Standard-A SuperSpeed plug fits the pre-SuperSpeed Standard-A receptacle. (All other SuperSpeed plugs cannot be attached to pre-SuperSpeed receptacles.)

For any devices to have a SuperSpeed link, all the connectors between them must be Type‑C or SuperSpeed.

Every USB cable predating USB‑C had an A plug at one end and a B plug at the other (with the rare exception of one special A–A configuration with certain conductors omitted, for operating system debugging and other host-to-host connection applications).[2]: §5.5.2 In a USB‑C-to-legacy cable, the Type‑C plug is electrically marked to take the role complementary to the connector at the opposite end, A for B and B for A. When a modern C–C cable is used, the two connected devices communicate to determine which takes which role.

USB On-The-Go connectors

[edit]Before USB‑C, USB On-The-Go (OTG) introduced the concept of a device that could switch roles, performing either the host role or peripheral device role, as needed, depending simply on which type of plug was attached. An OTG device was required to have one, and only one, USB connector: a Micro-AB receptacle or, before Micro-USB, a Mini-AB receptacle.

The Micro-AB receptacle is capable of accepting the Micro-A or Micro-B plug of any of the allowed cables and adapters as defined in revision 1.01 of the Micro-USB specification.

Since a Type-AB receptacle allows either an A or an B plug to be attached, each corresponding A and B plug design has an ID contact to indicate electrically whether the plug is the A or the B end of its cable: In an A plug the ID contact is connected to GND, and in a B plug it is not. Typically, a pull-up resistor in the device is used to detect the presence or absence of the GND connection.

An OTG device with an A plug inserted is called the A-device and is responsible for powering the USB interface when required, and by default assumes the role of host. An OTG device with a B plug inserted is called the B-device and by default assumes the role of peripheral. If an application on the On-The-Go device requires the role of host, then the Host Negotiation Protocol (HNP) is used to temporarily transfer the host role to the OTG device.

USB-C

[edit]

The USB-C connector supersedes all earlier USB connectors, the Mini DisplayPort connector and the Lightning connector since 2025.[32] It is used for all USB protocols and for Thunderbolt (3 and later), DisplayPort (1.2 and later), and others. Developed at roughly the same time as the USB 3.1 specification, but distinct from it, the USB-C Specification 1.0 was finalized in August 2014[33] and defined a new small reversible connector for all USB and some other devices.[34] The USB-C plug connects both to hosts and to peripheral devices, as well as to chargers and power supplies, replacing all of the preceding USB connectors with a standard meant to be future-proof.[33][35]

The 24-pin double-sided connector provides four power–ground pairs, two differential pairs for USB 2.0 data (though only one pair is implemented in a USB-C cable), four pairs for SuperSpeed data bus (only two pairs are used in USB 3.1 mode), two "sideband use" pins, VCONN +5 V power for active cables, and a configuration pin for cable orientation detection and dedicated biphase mark code (BMC) configuration data channel (CC).[36][37] Type-A and Type-B adaptors and cables are required for older hosts and devices to plug into USB-C hosts and devices. Adapters and cables with a USB-C receptacle are not allowed.[38]

A Full-Featured USB cable is a Type‑C-to-Type‑C cable that supports USB 2.0, USB 3.2 and USB4 data operation, and a Full-Featured Type‑C receptacle likewise supports the same full set of protocols.[39] It contains a full set of wires and is electronically marked (E-marked): It contains an E-marker chip that responds to the USB Power Delivery Discover Identity command, a kind of vendor-defined message (VDM) sent over the configuration data channel (CC). Using this command, the cable reports its current capacity, maximum speed, and other parameters.[40]: §4.9 Full-Featured USB Type-C devices are a mechanic prerequisite for multi-lane operation (USB 3.2 Gen 1×2, USB 3.2 Gen 2×2, USB4 2×2, USB4 3×2, USB Gen 4 Asymmetric).[40]

USB-C devices support power currents of 1.5 A and 3.0 A over the 5 V power bus in addition to baseline 900 mA. These higher currents can be negotiated through the configuration line. Devices can also use the full Power Delivery specification using both BMC-coded configuration line and the legacy BFSK-coded VBUS line.[40]: §4.6.2.1

Connector dimensions

[edit]| Connector Type | Width (mm) | Height (mm) | Depth (mm) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard-A | 12.35 | 4.5 | 15.2 | Original full-size USB connector found on computers and hubs |

| Standard-B | 11.1 | 7.0 | 12.0 | Square-shaped connector commonly used on printers and external drives |

| Mini-A | 7.5 | 3.0 | 5.0 | Deprecated smaller connector, trapezoidal shape |

| Mini-B | 7.5 | 3.0 | 5.0 | Deprecated smaller connector, trapezoidal shape |

| Micro-A | 6.85 | 1.8 | 6.0 | Small connector for mobile devices, trapezoidal shape |

| Micro-B | 6.85 | 1.8 | 6.0 | Small connector for mobile devices, trapezoidal shape |

| Micro-AB | 6.85 | 1.8 | 6.0 | OTG connector that accepts both Micro-A and Micro-B plugs |

| USB-C | 8.34 | 2.56 | 7.5 | Modern reversible connector with oval shape |

These dimensions are for the receptacle openings only and do not include the surrounding plastic or metal housing.[citation needed]

| Connector Type | Width (mm) | Height (mm) | Length (mm) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard-A | 11.5 | 4.0 | 14.5 | Original full-size USB connector found on cables |

| Standard-B | 10.5 | 6.5 | 11.5 | Square-shaped connector commonly used on device cables |

| Mini-A | 7.0 | 2.5 | 4.5 | Deprecated smaller connector, trapezoidal shape |

| Mini-B | 7.0 | 2.5 | 4.5 | Deprecated smaller connector, trapezoidal shape |

| Micro-A | 6.0 | 1.3 | 5.5 | Small connector for mobile devices, trapezoidal shape |

| Micro-B | 6.0 | 1.3 | 5.5 | Small connector for mobile devices, trapezoidal shape |

| USB-C | 7.9 | 2.1 | 7.0 | Modern reversible connector with oval shape |

These dimensions are for the plug body only and do not include the cable strain relief or overmold.[citation needed]

Compatibilities

[edit]Before the specification of the Type‑C plug, virtually every USB cable had one Type‑A plug at one end and one Type‑B plug at the other end of the cable. The Type‑A plug connects only upstream, either directly to a DFP of the host or indirectly, by connecting to a DFP of a hub that itself connects, directly or indirectly, to the host. The Type‑B plug connects only downstream, either directly to the single UFP of a peripheral device or to the UFP of a hub to which further hubs and peripheral devices can be connected. An On-The-Go device has a single Type‑AB port (either Micro‑AB or Mini‑AB) and takes either role according to the plug attached. In a Type‑C–legacy cable, the Type‑C plug is electronically marked to complement the plug at the opposite end: When the legacy plug is a Type‑A, the Type‑C plug is marked as B, and when the legacy plug is a Type‑B, the Type‑C is marked A. A device with a Type‑C receptacle may be capable of taking either role or my only function as one or the other. If a Type‑C plug marked as A or B is connected to a device incapable of taking the necessary role, no communication occurs. When two devices, each capable of taking either role, are connected through a Type‑C–Type‑C cable, there is a negotiation to determine which is the A device and which is the B.

Every connector supports protocols supported by its predecessors, and Type‑C, by design, renders all other USB connectors redundant.

| Plug | Compatible receptacles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | USB4 2.0[a] / USB4 / USB 3.2[b] | Type‑C[c] |

Type‑C | ||||

| Legacy | USB 3.x [d] |

Host (Type‑A) | USB 3.0 Standard‑A |

USB 3.0 Standard‑A |

USB 2.0 Standard‑A[e][f] | ||

| USB 3.0 Micro‑A[g] |

USB 3.0 Micro‑AB[h] | ||||||

| Peripheral (Type‑B) | USB 3.0 Standard‑B

|

USB 3.0 Standard‑B

| |||||

| USB 3.0 Micro‑B |

USB 3.0 Micro‑AB |

USB 3.0 Micro‑B | |||||

| USB 2.0 and earlier[f] | Host (Type‑A) | USB 2.0 Standard‑A |

USB 3.0 Standard‑A[e] |

USB 2.0 Standard‑A | |||

| USB 2.0 Micro‑A[g] |

USB 3.0 Micro‑AB[e] |

USB 2.0 Micro‑AB[h] | |||||

| Mini‑A[i] |

Mini‑AB[i] |

Mini‑A[i] | |||||

| Peripheral (Type‑B) | USB 2.0 Standard‑B

|

USB 3.0 Standard‑B[e]

|

USB 2.0 Standard‑B

| ||||

| USB 2.0 Micro‑B |

USB 3.0 Micro‑AB[e][h] |

USB 3.0 Micro‑B[e] |

USB 2.0 Micro‑AB[h] |

USB 2.0 Micro‑B | |||

| Mini‑B |

Mini‑AB[i] |

Mini‑B | |||||

| Receptacle | Compatible plugs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | USB4 2.0[a] / USB4 / USB 3.2[b] | Type‑C[c] |

Type‑C | ||||

| Legacy | USB 3.x [d] |

Host (Type‑A) | USB 3.0 Standard‑A |

USB 3.0 Standard‑A |

USB 2.0 Standard‑A[e] | ||

| Peripheral (Type‑B) | USB 3.0 Standard‑B

|

USB 3.0 Standard‑B

|

USB 2.0 Standard‑B[e]

| ||||

| USB 3.0 Micro‑B |

USB 3.0 Micro‑B |

USB 2.0 Micro‑B[e] | |||||

| On-The-Go (Type‑AB) | USB 3.0 Micro‑AB[h] |

USB 3.0 Micro‑A[g] |

USB 3.0 Micro‑B |

USB 2.0 Micro‑A[g][e] |

USB 2.0 Micro‑B[e] | ||

| USB 2.0 and earlier[f] | Host (Type‑A) | USB 2.0 Standard‑A |

USB 3.0 Standard‑A[e] |

USB 2.0 Standard‑A | |||

| Mini‑A[i] |

Mini‑A[i] | ||||||

| Peripheral (Type‑B) | USB 2.0 Standard‑B

|

USB 2.0 Standard‑B

| |||||

| USB 2.0 Micro‑B |

USB 2.0 Micro‑B | ||||||

| Mini‑B |

Mini‑B | ||||||

| On-The-Go (Type‑AB) | USB 2.0 Micro‑AB[h] |

USB 2.0 Micro‑A[g] |

USB 2.0 Micro‑B | ||||

| Mini‑AB[i][h] |

Mini‑A[i] |

Mini‑B | |||||

Remarks:

- ^ a b USB4 2.0: Up to 80 Gbit/s each direction, or 120 in either direction and 40 the other

- ^ a b USB 3.x: 20, 10, or 5 Gbit/s, and USB 2.0: 480, 12, or 1.2 Mbit/s

- ^ a b Also standard for Thunderbolt 3 and later. Also supports DisplayPort Alternate Mode.

- ^ a b USB 3.x (one lane only): 10, or 5 Gbit/s, and USB 2.0: 480, 12, or 1.2 Mbit/s

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Compatible, limited to the capabilities of USB 2.0

- ^ a b c USB 2.0: 480, 12, or 1.2 Mbit/s

- ^ a b c d e There is no Micro‑A–specific receptacle.

- ^ a b c d e f g A device with a Type‑AB receptacle accepts both Type‑A and Type‑B plugs and the pluged devices function either as the host or as a peripheral device, accordingly: When the Type‑A plug of a cable is connected, the device with the Type‑AB receptacle functions as the host; when the Type‑B plug end is connected, it functions as a peripheral device.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Deprecated.

| Current | Legacy | Deprecated | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type-C |

USB 3.0 Standard‑A |

USB 3.0 Micro‑A |

USB 2.0 Standard‑A |

USB 2.0 Micro‑A |

Mini‑A[16] | ||

| Current | Type‑C |

Up to 80 Gbit/s, or 120 Gbit/s either direction and 40 the other (USB4 Gen 4)[39] |

Up to 10 Gbit/s (USB 3.2 Gen 2×1)[39] |

Prohibited[39][c][d] | Up to 480 Mbit/s half duplex (USB 2.0)[39] | Prohibited[39][c][d] | Prohibited[16][39][c][d] |

| Legacy | USB 3.0 Standard‑B

|

Up to 10 Gbit/s (USB 3.2 Gen 2×1)[39] |

Up to 10 Gbit/s (USB 3.2 Gen 2×1)[2] |

— | |||

| USB 3.0 Micro‑B | |||||||

| USB 2.0 Standard‑B

|

Up to 480 Mbit/s half duplex (USB 2.0)[39] | — | Up to 480 Mbit/s half duplex (USB 2.0)[42] | Prohibited[e][11][d] | Prohibited[16][d] | ||

| USB 2.0 Micro‑B |

Up to 480 Mbit/s half duplex (USB 2.0)[11] | Up to 480 Mbit/s half duplex (USB 2.0)[11] | |||||

| Mini‑B |

Prohibited[e][11][d] | ||||||

- ^ a b Every legacy USB cable has an A end and a B end, with the exception of a single special Type‑A–Type‑A cable type for operating system debugging and other host-to-host connection applications: This cable has a USB 3.0 Standard‑A plug at each end but with no connections for power (VBUS) or for the legacy data channel of USB 2 and USB 1 (D−, D+).[2] [43] This exception, while safe, has no common application. Also there are valid A-to-A assemblies, referred to loosely as cables (such as the Easy Transfer Cable), which are actually not simply cables but active peripheral devices: In USB terms, such a product is two peripherals, each one seen by one of the hosts to which the "cable" is connected.

- ^ a b Some devices, e.g. some smartphones, are defectively designed in that they can function as USB hosts, not just as peripheral devices, except that they have, incorrectly, Micro‑B or Mini‑B receptacles instead of ‑AB receptacles. Nonstandard cables to connect peripheral devices to these defective devices exist: Such a cable has a proper Type‑B plug at one end and at the other a plug electrically marked Type‑A that is mechanically Type‑B, allowing insertion and causing such a defective device to take the host role. When connected to a valid device that correctly has a Type‑B receptacle damage is unlikely since all Type‑B ports are unpowered by default, but no communication occurs.[41]

- ^ a b c A cable with a Type‑C plug and a plug that fits an Type‑AB receptacle (i.e. Micro or Mini) can be confusing in that the directionality of the cable may be unclear and its directionality determines whether an attached device takes the host or peripheral device role. To avoid this problem, the Type‑C connector is always the A end of such cables with the other end a Micro‑B or a Mini‑B. Type‑C–Micro‑A and Type‑C–Mini‑A cables are prohibited.

- ^ a b c d e f The USB standards do not allow cables with every combination of one Type‑A and one Type‑B plug, and nonstandard cables cannot be certified or marked with USB logos. However, cables with non-standard combinations of plugs exist. Provided that the one end is Type‑A and the other Type‑B (that one plug is an Type‑A type or Type‑C and the other a Type‑B type or Type‑C) a cable may function.

- ^ a b There is no standard cable to directly connect a peripheral device with a Standard‑B or Mini‑B port directly to an On-The-Go host. Instead, a cable with a Standard‑A plug is used, and the Standard‑A plug is connected to a (specifically allowed) adapter that connects to the Micro‑AB receptacle of the On-The-Go host.

In addition to the above cable assemblies comprising two plugs, receptacles are allowed in three adapter assemblies:

- Two legacy adapter assemblies for compatibility with equipment that predates USB‑C:

- One older adapter, itself designated legacy, predating USB‑C: Standard‑A receptacle to Micro‑A plug, giving a compact On-The-Go device, such as a camera or smartphone, a Standard‑A port for connecting peripherals, such as printers and mass storage devices. That is, to connect a Standard‑A plug to a Micro‑AB receptacle.[11][10] (All USB connectors except Type‑C were designated legacy in 2014.[44])

Plug Legacy

receptacle |

Current | Legacy |

|---|---|---|

| Type‑C |

USB 2.0 Micro‑A[c] | |

| USB 3.0 Standard‑A[b] |

Up to 10 Gbit/s (USB 3.2 Gen 2×1)[39] to connect a legacy peripheral device to a Type‑C host |

— |

| USB 2.0 Micro‑B |

Up to 480 Mbit/s half duplex (USB 2.0)[39] to connect a legacy charger or host to a Type‑C peripheral device | |

| USB 2.0 Standard‑A |

— | Up to 480 Mbit/s half duplex (USB 2.0)[11] to connect a peripheral device to an On-The-Go device |

Internal connectors

[edit]

A computer's motherboard includes pin headers for connecting the motherboard to the USB ports on the computer case. The following types are standardized:[45]

- 9-pin header for two USB 1.1/2.0 Type-A ports. There is also a 5-pin variant for a single port. Motherboards made before 2000 may have other layouts.[46]

- 19-pin header for a two USB 3.0 (also known as 3.1/3.2 Gen 1) Type-A ports. This is not backwards compatible with the 9-pin header,[47] There is no standard for running a newer signal (e.g. Gen 2) over this header, but there is enough signal integrity to do so in practice.

- "Type-E" ports, which are not pin headers with an array of pins, but a port to plug into:

- 20-pin Key-A for a single full-featured Type-C, providing up to 80 Gbps in the case of USB4 2.0. (As the original definition is for USB 3.1 Gen 2 [aka USB 3.2 Gen 2, ×2 for two lanes in USB-C], the electrical connection between the case-port and the header may not be of high enough quality for 80 Gbps. USB4 40 Gbps should be achievable as it requires the same cable quality as USB 3.1 Gen 2.)[48][49] It can also be used to provide one Type-A port up to USB 3.1/3.2 Gen 2. There is officially no provision for providing two Type-A ports from this header as it only provides one pair of legacy (USB 1.1/2.0) D+ and D-.[48] The 20-pin headers are not backwards compatible with either 9 or 19-pin.`

- 20-pin Key-B for two Type-A ports up to USB 3.1/3.2 Gen 2. This header differs from Key-A by reassigning the CC and SBU pins to legacy 1.1/2.0 data (D+, D-) and power (VBUS, GND). Physical keying prevents mixing of Key-A and Key-B port (headers) and plugs.[48]

- 40-pin, which is functionally the same as two 20-pin Key-A headers put side-by-side. Supports either two Type-C ports, one Type-C plus one Type-A port, or two Type-A ports. A 40-pin port can accept a 20-pin Key-A plug.[48]

All these systems are electrically compatible with each other like the USB external connectors are, so passive adapters can be used to mitigate physical incompatibilities, e.g. by converting 19-pin headers to 9-pin headers. It is even possible to convert a 19-pin header to a 20-pin header for USB-C use, albeit without CC and SBU functionality.

The shape and contact positions, i.e. footprints, for USB receptables soldered onto circuit boards (surface-mount devices) is partly standardized.

In addition, there is an embedded USB (eUSB2) specification describing using USB 2.0 for the communication between two chips on the same circuit board. It uses a lower signaling voltage compared to regular USB 2.0.[50]

Proprietary connectors and formats

[edit]Manufacturers of personal electronic devices might not include a USB standard connector on their product for technical or marketing reasons.[51] For example, Olympus has been using a special cable called CB-USB8, one end of which has a special contact. Some manufacturers provide proprietary cables, such as Apple with the Lightning cable, that permit their devices to physically connect to a USB standard port. Full functionality of proprietary ports and cables with USB standard ports is not assured; for example, some devices only use the USB connection for battery charging and do not implement any data transfer functions.[52]

Cabling

[edit]

The D± signals used by low, full, and high speed are carried over a twisted pair (typically unshielded) to reduce noise and crosstalk. SuperSpeed uses separate transmit and receive differential pairs, which additionally require shielding (typically, shielded twisted pair but twinax is also mentioned by the specification). Thus, to support SuperSpeed data transmission, cables contain twice as many wires and are larger in diameter.[53]

The USB 1.1 standard specifies that a standard cable can have a maximum length of 5 metres (16 ft 5 in) with devices operating at full speed (12 Mbit/s), and a maximum length of 3 metres (9 ft 10 in) with devices operating at low speed (1.5 Mbit/s).[54][55][56]

USB 2.0 provides for a maximum cable length of 5 metres (16 ft 5 in) for devices running at high speed (480 Mbit/s). The primary reason for this limit is the maximum allowed round-trip delay of about 1.5 μs. If USB host commands are unanswered by the USB device within the allowed time, the host considers the command lost. When adding USB device response time, delays from the maximum number of hubs added to the delays from connecting cables, the maximum acceptable delay per cable amounts to 26 ns.[56] The USB 2.0 specification requires that cable delay be less than 5.2 ns/m (1.6 ns/ft, 192000 km/s), which is close to the maximum achievable transmission speed for standard copper wire.

The USB 3.0 standard does not directly specify a maximum cable length, requiring only that all cables meet an electrical specification: for copper cabling with AWG 26 wires the maximum practical length is 3 metres (9 ft 10 in).[57]

Power

[edit]Downstream USB connectors supply power at a nominal 5 V DC via the V_BUS pin to upstream USB devices.

Voltage tolerance and limits

[edit]

The tolerance on V_BUS at an upstream (or host) connector was originally ±5% (i.e. could lie anywhere in the range 4.75 V to 5.25 V). With the release of the USB Type-C specification in 2014 and its 3 A power capability, the USB-IF elected to increase the upper voltage limit to 5.5 V to combat voltage droop at higher currents.[58] The USB 2.0 specification (and therefore implicitly also the USB 3.x specifications) was also updated to reflect this change at that time.[59] A number of extensions to the USB Specifications have progressively further increased the maximum allowable V_BUS voltage: starting with 6.0 V with USB BC 1.2,[60] to 21.5 V with USB PD 2.0[61] and 50.9 V with USB PD 3.1,[61] while still maintaining backwards compatibility with USB 2.0 by requiring various forms of handshake before increasing the nominal voltage above 5 V.

USB PD continues the use of the bilateral 5% tolerance, with allowable voltages of PDO ±5% (e.g. for a PDO of 9.0 V, the minimum and maximum limits are 8.55 V and 9.45 V, respectively). Overshoot (or undershoot) not exceeding ±0.5 V is allowed for up to 275 msec when changing to a higher (or lower) voltage.[61]

There are several minimum allowable voltages defined at different locations within a chain of connectors, hubs, and cables between an upstream host (providing the power) and a downstream device (consuming the power). To allow for voltage drops, the voltage at the host port, hub port, and device are specified to be at least 4.75 V, 4.4 V, and 4.35 V respectively by USB 2.0 for low-power devices,[a] but must be at least 4.75 V at all locations for high-power[b] devices (however, high-power devices are required to operate as a low-powered device so that they may be detected and enumerated if connected to a low-power upstream port). The USB 3.x specifications require that all devices must operate down to 4.00 V at the device port.

Unlike USB 2.0 and USB 3.2, USB4 does not define its own VBUS-based power model. Power for USB4 operation is established and managed as defined in the USB Type-C Specification and the USB PD Specification.

Allowable current draw

[edit]| Specification | Current (max.) | Voltage | Power (max.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-power device | 100 mA | 5 V | 0.50 W |

| Low-power SuperSpeed (USB 3.0) device | 150 mA | 5 V | 0.75 W |

| High-power device | 500 mA[a] | 5 V | 2.5 W |

| High-power SuperSpeed (USB 3.0) device | 900 mA[b] | 5 V | 4.5 W |

| Battery Charging (BC) 1.2 | 1.5 A | 5 V | 7.5 W |

| Single-lane SuperSpeed+ (USB 3.2 Gen 2×1) device | 1.5 A[c] | 5 V | 7.5 W |

| Power Delivery 3.0 SPR | 3 A | 5 V | 15 W |

| Power Delivery 3.0 SPR | 3 A | 9 V | 27 W |

| Power Delivery 3.0 SPR | 3 A | 15 V | 45 W |

| Power Delivery 3.0 SPR | 3 A | 20 V | 60 W |

| Power Delivery 3.0 SPR Type-C | 5 A[d] | 20 V | 100 W |

| Power Delivery 3.1 EPR Type-C | 5 A[d] | 28 V[e] | 140 W |

| Power Delivery 3.1 EPR Type-C | 5 A[d] | 36 V[e] | 180 W |

| Power Delivery 3.1 EPR Type-C | 5 A[d] | 48 V[e] | 240 W |

| |||

The limit to device power draw is stated in terms of a unit load which is 100 mA for USB 2.0, or 150 mA for SuperSpeed (i.e. USB 3.x) devices. Low-power devices may draw at most 1 unit load, and all devices must act as low-power devices before they are configured. A high-powered device must be configured, after which it may draw up to 5 unit loads (500 mA), or 6 unit loads (900 mA) for SuperSpeed devices, as specified in its configuration because the maximum power may not always be available from the upstream port.[62][63][64][65]

A bus-powered hub is a high-power device providing low-power ports. It draws one unit load for itself and one unit load for each of at most four ports. The hub may also have some non-removable devices in place of ports, a common example being a keyboard with two low-power A ports included, sufficient for pointing devices such as mice. (Such a keyboard is, in USB terms, one hub and one peripheral device.) A self-powered hub is a device that provides high-power ports by supplementing the power supply from the host with its own external supply. Optionally, the hub controller may draw power for its operation as a low-power device, but all high-power ports must draw from the hub's self-power.

Where devices (for example, high-speed disk drives) require more power than a high-power device can draw,[66] they function erratically, if at all, from bus power of a single port. USB provides for these devices as being self-powered. However, such devices may come with a Y-shaped cable that has two USB plugs (one for power and data, the other for only power), so as to draw power as two devices.[67] Such a cable is non-standard, with the specification stating that "use of a 'Y' cable (a cable with two A-plugs) is prohibited on any USB peripheral", meaning that "if a USB peripheral requires more power than allowed by the USB specification to which it is designed, then it must be self-powered."[68]

USB battery charging

[edit]USB Battery Charging (BC) defines a charging port, which may be a charging downstream port (CDP), with data, or a dedicated charging port (DCP), without data. Dedicated charging ports can be found on USB power adapters to run and charge attached devices and charge battery packs. Charging ports on a host with both kinds will be labeled.[69]

The charging device identifies a charging port by non-data signaling on the D+ and D− terminals. A dedicated charging port places a resistance not exceeding 200 Ω across the D+ and D− terminals.[69]: §1.4.7; table 5-3

Per the base specification, any device attached to a standard downstream port (SDP) must initially be a low-power device, with high-power mode contingent on later USB configuration by the host. Charging ports, however, can immediately supply between 0.5 and 1.5 A of current. The charging port must not apply current limiting below 0.5 A, and must not shut down below 1.5 A or before the voltage drops to 2 V.[69]

Since these currents are larger than in the original standard, the extra voltage drop in the cable reduces noise margins, causing problems with High Speed signaling. Battery Charging Specification 1.1 specifies that charging devices must dynamically limit bus power current draw during High Speed signaling;[70] 1.2 specifies that charging devices and ports must be designed to tolerate the higher ground voltage difference in High Speed signaling.

Revision 1.2 of the specification was released in 2010. It made several changes and increased limits, including allowing 1.5 A on charging downstream ports for unconfigured devices—allowing High Speed communication while having a current up to 1.5 A. Also, support was removed for charging-port detection via resistive mechanisms.[71]

Before the Battery Charging Specification was defined, there was no standardized way for the portable device to inquire how much current was available. For example, Apple's iPod and iPhone chargers indicate the available current by voltages on the D− and D+ lines (sometimes also called "Apple Brick ID"). When D+ = D− = 2.0 V, the device may pull up to 900 mA. When D+ = 2.0 V and D− = 2.8 V, the device may pull up to 1 A of current.[72] When D+ = 2.8 V and D− = 2.0 V, the device may pull up to 2 A of current.[73] The maximum power delivered with this method was 12.48 W (5.2 V, 2.4 A),[74] with D+ = D- = 2.7 V.[75]

Accessory Charger Adapter

[edit]A USB On-The-Go (OTG) device has a single Micro-AB port (or, formerly, a Mini-AB port) for charging as well as for connecting either to a host or to peripheral devices. An Accessory Charger Adapter (ACA) allows simultaneous connection to a charger and either to a host or to peripheral devices, with the charger providing power to both the OTG device and any connected peripheral devices. For example, a keyboard can connect to a smartphone, or a printer, a keyboard, and a flash drive can connect to a smartphone through a USB hub, with the ACA capable of charging the smartphone and powering the keyboard, flash drive, and hub; or the smartphone can connect to a computer (host) that does not provide full power for charging, while the ACA provides full charging power.

An Accessory Charger Adapter has three ports: OTG, Charger, and Accessory. The OTG port connects to the On-The-Go device through a permanently-attached (captive) cable with a (mechanically) Micro-A plug. The Charger port is visibly marked Charger Only and does not support USB communication with the OTG device. It is either a Micro-B receptacle or a captive cable; such a captive cable either has a Standard-A plug or is permanently attached to a charger. The Accessory port is either a Micro-AB or Standard-A receptacle. An A receptacle by definition can only connect to peripheral devices; the Micro-AB receptacle can be used to connect either a host or peripheral devices. The captive plug of the OTG port is unusual in that, unlike a normal Micro-A plug, which is not only mechanically identifiable as an A plug but also electrically marked as such (causing an OTG device to behave as a host), the Micro-A plug of the Accessory Charger Adapter electrically becomes B when a Micro-B plug is connected to the (Micro-AB) Accessory port, causing the OTG device to behave as a peripheral.[69]: §6

USB Power Delivery

[edit]

| Profile | +5 V | +12 V | +20 V |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Reserved | ||

| 1 | 3.0 A, 15 W[a] | — | — |

| 2 | 1.5 A, 18 W | ||

| 3 | 3.0 A, 36 W | ||

| 4 | 3.0 A, 60 W | ||

| 5 | 5.0 A, 60 W | 5.0 A, 100 W | |

| |||

| Power | Minimum USB‑C cable required |

Voltage | Current | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 15 W | Any[A][77][78][79] | 5 V | ≤ 3.0 A | |||||

| ≤ 27 W | 9 V | |||||||

| ≤ 45 W | 15 V | |||||||

| ≤ 60 W | 20 V | |||||||

| ≤ 100 W | 5 A, or 100 W[B] | 20 V | ≤ 5.0 A | |||||

| ≤ 140 W[C] | 240 W[B][D][79] | 28 V | ≤ 5.0 A | |||||

| ≤ 180 W[C] | 36 V | |||||||

| ≤ 240 W[C] | 48 V | |||||||

In July 2012, the USB Promoters Group announced the finalization of the USB Power Delivery (USB-PD) specification (USB PD rev. 1), an extension that specifies using certified PD aware USB cables with standard USB Type-A and Type-B connectors to deliver increased power (more than the 7.5 W maximum allowed by the previous USB Battery Charging specification) to devices with greater power demands. (USB-PD A and B plugs have a mechanical mark while Micro plugs have a resistor or capacitor attached to the ID pin indicating the cable capability.) USB-PD Devices can request higher currents and supply voltages from compliant hosts—up to 2 A at 5 V (for a power consumption of up to 10 W), and optionally up to 3 A or 5 A at either 12 V (36 W or 60 W) or 20 V (60 W or 100 W).[80] In all cases, both host-to-device and device-to-host configurations are supported.[81]

The intent is to permit uniformly charging laptops, tablets, USB-powered disks and similarly higher-power consumer electronics, as a natural extension of existing European and Chinese mobile telephone charging standards. This may also affect the way electric power used for small devices is transmitted and used in both residential and public buildings.[82][76] The standard is designed to coexist with the previous USB Battery Charging specification.[83]

The first Power Delivery specification (Rev. 1.0) defined six fixed power profiles for the power sources. PD-aware devices implement a flexible power management scheme by interfacing with the power source through a bidirectional data channel and requesting a certain level of electrical power, variable up to 5 A and 20 V depending on supported profile. The power configuration protocol can use BMC coding over the configuration channel (CC) wire if one is present, or a 24 MHz BFSK-coded transmission channel on the VBUS line.[76]

The USB Power Delivery specification revision 2.0 (USB PD Rev. 2.0) has been released as part of the USB 3.1 suite.[77][84][85] It covers the USB-C cable and connector with a separate configuration channel, which now hosts a DC coupled low-frequency BMC-coded data channel that reduces the possibilities for RF interference.[86] Power Delivery protocols have been updated to facilitate USB-C features such as cable ID function, Alternate Mode negotiation, increased VBUS currents, and VCONN-powered accessories.

As of specification revision 2.0, version 1.2, the six fixed power profiles for power sources have been deprecated.[87] USB PD Power Rules replace power profiles, defining four normative voltage levels at 5, 9, 15, and 20 V. Instead of six fixed profiles, power supplies may support any maximum source output power from 0.5 W to 100 W.

The USB Power Delivery specification revision 3.0 defines an optional Programmable Power Supply (PPS) protocol that allows granular control over VBUS output, allowing a voltage range of 3.3 to 21 V in 20 mV steps, and a current specified in 50 mA steps, to facilitate constant-voltage and constant-current charging. Revision 3.0 also adds extended configuration messages and fast role swap and deprecates the BFSK protocol.[78]: Table 6.26 [88][89]

On January 8, 2018, USB-IF announced the Certified USB Fast Charger logo for chargers that use the Programmable Power Supply (PPS) protocol from the USB Power Delivery 3.0 specification.[90]

In May 2021, the USB PD promoter group launched revision 3.1 of the specification.[79] Revision 3.1 adds Extended Power Range (EPR) mode which allows higher voltages of 28, 36, and 48 V, providing up to 240 W of power (48 V at 5 A), and the "Adjustable Voltage Supply" (AVS) protocol which allows specifying the voltage from a range of 15 to 48 V in 100 mV steps.[91][92] Higher voltages require electronically marked EPR cables that support 5 A operation and incorporate mechanical improvements required by the USB Type-C standard revision 2.1; existing power modes are retroactively renamed Standard Power Range (SPR). In October 2021 Apple introduced a 140 W (28 V 5 A) GaN USB PD charger with new MacBooks,[93] and in June 2023 Framework introduced a 180 W (36 V 5 A) GaN USB PD charger with the Framework 16.[94]

In October 2023, the USB PD promoter group launched revision 3.2 of the specification. The AVS protocol now works with the old standard power range (SPR), down to a minimum of 9 V.[95]: §10.2.2

Prior to Power Delivery, mobile phone vendors used custom protocols to exceed the 7.5 W cap on the USB Battery Charging Specification (BCS). For example, Qualcomm's Quick Charge 2.0 is able to deliver 18 W at a higher voltage, and VOOC delivers 20 W at the normal 5 V.[96] Some of these technologies, such as Quick Charge 4, eventually became compatible with USB PD again.[97]

Charge controllers

[edit]As of 2024[update] mainstream USB PD charging controllers support up to 100 W through a single port, with a few up to 140 W[98][99] and custom built up to 180 W.[94][needs update]

Sleep-and-charge ports

[edit]

Sleep-and-charge USB ports can be used to charge electronic devices even when the computer that hosts the ports is switched off. Normally, when a computer is powered off the USB ports are powered down. This feature has also been implemented on some laptop docking stations allowing device charging even when no laptop is present.[100] On laptops, charging devices from the USB port when it is not being powered from AC drains the laptop battery; most laptops have a facility to stop charging if their own battery charge level gets too low.[101]

On Dell, HP and Toshiba laptops, sleep-and-charge USB ports are marked with the standard USB symbol with an added lightning bolt or battery icon on the right side.[102] Dell calls this feature PowerShare,[103] and it needs to be enabled in the BIOS. Toshiba calls it USB Sleep-and-Charge.[104] On Acer Inc. and Packard Bell laptops, sleep-and-charge USB ports are marked with a non-standard symbol (the letters USB over a drawing of a battery); the feature is called Power-off USB.[105] Lenovo calls this feature Always On USB.[106]

Mobile device charger standards

[edit]In China

[edit]Starting in 2007, all new mobile phones applying for a license in China are required to use a USB port as a power port for battery charging.[107][108] This was the first standard to use the convention of shorting D+ and D− in the charger.[109]

OMTP/GSMA Universal Charging Solution

[edit]In September 2007, the Open Mobile Terminal Platform group (a forum of mobile network operators and manufacturers such as Nokia, Samsung, Motorola, Sony Ericsson, and LG) announced that its members had agreed on Micro-USB as the future common connector for mobile devices.[110][111]

The GSM Association (GSMA) followed suit on February 17, 2009,[112][113][114][115] and on April 22, 2009, this was further endorsed by the CTIA – The Wireless Association,[116] with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) announcing on October 22, 2009, that it had also embraced the Universal Charging Solution as its "energy-efficient one-charger-fits-all new mobile phone solution," and added: "Based on the Micro-USB interface, UCS chargers will also include a 4-star or higher efficiency rating—up to three times more energy-efficient than an unrated charger."[117]

EU smartphone power supply standard

[edit]In June 2009, the European Commission organized a voluntary Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to adopt micro-USB as a common standard for charging smartphones marketed in the European Union. The specification was called the common external power supply. The MoU lasted until 2014. The common EPS specification (EN 62684:2010) references the USB Battery Charging Specification and is similar to the GSMA/OMTP and Chinese charging solutions.[118][119] In January 2011, the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) released its version of the (EU's) common EPS standard as IEC 62684:2011.[120]

In 2022, the Radio Equipment Directive 2022/2380 made USB-C compulsory as a mobile phone charging standard from 2024, and for laptops from 2026.[121]

Faster-charging standards

[edit]A variety of (non-USB) standards support charging devices faster than the USB Battery Charging standard. When a device doesn't recognize the faster-charging standard, generally the device and the charger fall back to the USB battery-charging standard of 5 V at 1.5 A (7.5 W). When a device detects it is plugged into a charger with a compatible faster-charging standard, the device pulls more current or the device tells the charger to increase the voltage or both to increase power (the details vary between standards).[122]

Such standards include:[122][123]

- Apple "Brick ID" 2 A and 2.4 A charging (described above, does not use BC negotiaion)

- Google fast charging

- Huawei SuperCharge

- MediaTek Pump Express

- Motorola TurboPower

- Oppo Super VOOC Flash Charge, are also known as Dash Charge or Warp Charge on OnePlus devices and Dart Charge on Realme devices

- Qualcomm Quick Charge (QC)

- Samsung Adaptive Fast Charging

Non-standard devices

[edit]Some USB devices require more power than is permitted by the specifications for a single port. This is common for external hard and optical disc drives, and generally for devices with motors or lamps. Such devices can use an external power supply, which is allowed by the standard, or use a dual-input USB cable, one input of which is for power and data transfer, the other solely for power, which makes the device a non-standard USB device. Some USB ports and external hubs can, in practice, supply more power to USB devices than required by the specification but a standard-compliant device may not depend on this.

In addition to limiting the total average power used by the device, the USB specification limits the inrush current (i.e., the current used to charge decoupling and filter capacitors) when the device is first connected. Otherwise, connecting a device could cause problems with the host's internal power. USB devices are also required to automatically enter ultra low-power suspend mode when the USB host is suspended. Nevertheless, many USB host interfaces do not cut off the power supply to USB devices when they are suspended.[124]

Some non-standard devices use the USB 5 V power supply without participating in a proper USB network, which negotiates power draw with the host interface; these devices typically violate the standards by drawing more power than is allowed without negotiation. Examples include USB-powered keyboard lights, fans, mug coolers and heaters, battery chargers, miniature vacuum cleaners, and even miniature lava lamps. In most cases, these items contain no digital circuitry, and thus are not standard-compliant USB devices. This may cause problems with some computers, such as drawing too much current and damaging circuitry. Prior to the USB Battery Charging Specification, the USB specification required that devices connect in a low-power mode (100 mA maximum) and communicate their current requirements to the host, which then permits the device to switch into high-power mode.

Some devices predating USB Power Delivery, when plugged into charging ports, draw even more power (10 watts) than the Battery Charging Specification allows, using proprietary methods but without violating USB standards, maintaining full compatibility—the iPad is one such device;[125] it negotiates the current pull with data pin voltages.[72] Barnes & Noble Nook Color devices also require a special charger that can provide 1.9 A.[citation needed]

PoweredUSB

[edit]PoweredUSB is a proprietary extension, from long before USB Power Delivery, that adds four pins supplying up to 6 A at 5 V, 12 V, or 24 V. It is commonly used in point-of-sale systems to power peripherals such as barcode readers, credit card terminals, and printers.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Universal Serial Bus Specification (Technical report) (Revision 2.0 ed.). USB-IF. 2000-04-27. 6.4.4 Prohibited Cable Assemblies.

- ^ a b c d e f "USB 3.1 Legacy Cable and Connector Specification". USB Implementers Forum. 1.0. 2017-09-22. Archived from the original on 2019-04-13. Retrieved 2025-06-11.

- ^ a b c "Universal Serial Bus 3.0 Specification". USB Implementers Forum. 1.0. 2011-06-06. Archived from the original on 2013-12-30. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- ^ a b c "USB 2.0 Specification Engineering Change Notice (ECN) #1: Mini-B connector" (PDF). 2000-10-20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-12. Retrieved 2019-04-28 – via USB.org.

- ^ "USB connector guide". C2G. Archived from the original on 2014-04-21. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- ^ a b c d e "Universal Serial Bus Cables and Connectors Class Document – Revision 2.0" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. August 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-11.

- ^ Howse, Brett. "USB Type-C Connector Specifications Finalized". AnandTech. Archived from the original on 2017-03-18. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ^ Oji, Obi (January 2024). "ESD and Surge Protection for USB Interfaces – Application Note" (PDF). Texas Instruments.

- ^ "USB Pinout". UsbPinout.net. Archived from the original on 2014-06-17.

- ^ a b c "Universal Serial Bus Micro-USB Cables and Connectors Specification" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. 2007-04-04. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-15. Retrieved 2015-01-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Universal Serial Bus Micro-USB Cables and Connectors Specification". USB Implementers Forum. 1.01. 2007-04-04. Archived from the original on 2023-10-06. Retrieved 2025-02-27.

- ^ "Types of USB Cables: The Ultimate Guide". CDW.com. Retrieved 2025-03-20.

- ^ "Everything You Should Know About USB Types | USB FAQs". CMD Ltd. Retrieved 2025-03-20.

- ^ Quinnell, Richard A. (1996-10-24). "USB: a neat package with a few loose ends". EDN Magazine. Reed. Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ^ "What is the Difference between USB Type A and USB Type B Plug/Connector?". Archived from the original on 2017-02-07.

- ^ a b c d "Deprecation of the Mini-A and Mini-AB Connectors" (PDF) (Press release). USB Implementers Forum. 2007-05-27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-06. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- ^ "Consumer OTG Products must use the Micro-AB receptacle". USB Implementers Forum. March 2007. Archived from the original on 2025-01-27. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "ID Pin Resistance on Mini B-plugs and Micro B-plugs Increased to 1 Mohm". USB IF Compliance Updates. December 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- ^ "Mini Connectors Antiquated". USB Implementers Forum. March 2021. Archived from the original on 2025-02-12. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b Universal Serial Bus Cables and Connectors Class Document (PDF), Revision 2.0, USB Implementers Forum, August 2007, p. 6, archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-27, retrieved 2014-08-17

- ^ "Mobile phones to adopt new, smaller USB connector" (PDF) (Press release). USB Implementers Forum. 2007-01-04. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ^ "Micro-USB mobile phone/smartphone cable connector pinout diagram". pinoutguide.com. 2012-11-16. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ^ a b "Universal Serial Bus Micro-USB Cables and Connectors Specification to the USB 2.0 Specification, Revision 1.01". USB Implementers Forum. 2007-04-07. Archived from the original (ZIP) on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2010-11-18.

Section 1.3: Additional requirements for a more rugged connector that is durable past 10,000 cycles and still meets the USB 2.0 specification for mechanical and electrical performance was also a consideration. The Mini-USB could not be modified and remain backward compatible to the existing connector as defined in the USB OTG specification.

- ^ Peter. "Flashback: micro-USB brought order to charging and data transfer cables". GSMArena.com. Retrieved 2025-03-20.

- ^ "OMTP Local Connectivity: Data Connectivity". Open Mobile Terminal Platform. 2007-09-17. Archived from the original on 2008-10-15. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ^ "Universal phone charger standard approved—One-size-fits-all solution will dramatically cut waste and GHG emissions". ITU (press release). Pressinfo. 2009-10-22. Archived from the original on 2009-11-05. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ^ "Commission welcomes new EU standards for common mobile phone charger". Press Releases. Europa. 2010-12-29. Archived from the original on 2011-03-19. Retrieved 2011-05-22.

- ^ New EU standards for common mobile phone charger (press release), Europa, archived from the original on 2011-01-03

- ^ The following 10 biggest mobile phone companies have signed the MoU: Apple, LG, Motorola, NEC, Nokia, Qualcomm, Research In Motion, Samsung, Sony Ericsson, Texas Instruments (press release), Europa, archived from the original on 2009-07-04

- ^ "Nice Micro-USB Adapter Apple, Now Sell It Everywhere". Giga om. 2011-10-05. Archived from the original on 2012-08-26.

- ^ "Apple's Lightning to Micro-USB adapter now available in US, not just Europe anymore", Engadget, 2012-11-03, archived from the original on 2017-06-26

- ^ "Apple to complete its USB-C transition for AirPods and other accessories by 2025". 2023-09-17. Retrieved 2023-09-21.

- ^ a b Howse, Brett (2014-08-12). "USB Type-C Connector Specifications Finalized". Archived from the original on 2014-12-28. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- ^ Hruska, Joel (2015-03-13). "USB-C vs. USB 3.1: What's the difference?". ExtremeTech. Archived from the original on 2015-04-11. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ^ Ngo, Dong (2014-08-22). "USB Type-C: One Cable to Connect Them All". c.net. Archived from the original on 2015-03-07. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- ^ "Technical Introduction of the New USB Type-C Connector". Archived from the original on 2014-12-29. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ Smith, Ryan (2014-09-22). "DisplayPort Alternate Mode for USB Type-C Announced - Video, Power, & Data All Over Type-C". AnandTech. Archived from the original on 2014-12-18. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- ^ Universal Serial Bus Type-C Cable and Connector Specification Revision 1.1 (April 3, 2015), section 2.2, page 20

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Universal Serial Bus Type-C Cable and Connector Specification". USB Implementers Forum. 2.4. October 2024. Archived from the original on 2024-12-21. Retrieved 2025-02-28.

- ^ a b c Universal Serial Bus Type-C Cable and Connector Specification, Release 2.2. USB Implementers Forum (Technical report). USB 3.0 Promoter Group. October 2022. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ "On-The-Go and Embedded Host Supplement to the USB Revision 3.0 Specification" (PDF). USB.org. Revision 1.1. 2012-05-10.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus Specification". USB Implementers Forum. 2.0. 2000-04-27. Archived from the original on 2023-10-06. Retrieved 2025-03-23.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus 3.1 Legacy Connectors and Cable Assemblies Compliance Document" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. 1.1. 2018-04-03. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-11-27. Retrieved 2025-02-27.

- ^ a b c "Universal Serial Bus Type‑C Connectors and Cable Assemblies Compliance Document". USB Implementers Forum. 2.1b. June 2021. Retrieved 2025-02-27.

- ^ "Understanding Motherboard USB Headers and Ports | Newnex". newnex.com.

- ^ "FRONTX - Mother-board USB Pin Assignment - USB Header (pinout) Connection Guide". www.frontx.com.

- ^ "USB 3.0 INTERNAL CONNECTOR AND CABLE SPECIFICATION" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d "USB 3.1 FRONT-PANEL INTERNAL CONNECTOR AND CABLE, REVISION 1.1" (PDF). 2017.

- ^ "USB4™ Cable Electricals and System Design" (PDF).

- ^ "SSZT427 Technical article | TI.com". www.ti.com.

- ^ "Proprietary Cables vs Standard USB". anythingbutipod.com. 2008-04-30. Archived from the original on 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2013-10-29.

- ^ Friedman, Lex (2013-02-25). "Review: Logitech's Ultrathin mini keyboard cover makes the wrong tradeoffs". macworld.com. Archived from the original on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2013-10-29.

- ^ "What Is the USB 3.0 Cable Difference". Hantat. 2009-05-18. Archived from the original on 2011-12-11. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- ^ "USB Cable Length Limitations" (PDF). cablesplususa.com. 2010-11-03. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-11. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ "What is the Maximum Length of a USB Cable?". Techwalla.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- ^ a b "USB Frequently Asked Questions: Cables and Long-Haul Solutions". USB.org. Archived from the original on 2014-01-15. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ Axelson, Jan. "USB 3.0 Developers FAQ". Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ^ "USB Type-C Revision 1.0" (PDF). USB 3.0 Promoter Group. 2021-03-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-03. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ^ "USB ECN USB 2.0 VBUS Max Limit". USB-IF. 2021-11-03. Archived from the original on 2021-11-03. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ^ "Battery Charging v1.2 Spec and Adopters Agreement" (PDF (Zipped)). USB.org. 2015-03-15. Table 5-1 Voltages. Archived (PDF (Zipped)) from the original on 2021-11-03. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ^ a b c "USB Power Delivery Specifications 2.0 and 3" (PDF (Zipped)). USB.org. 2021-10-26. Archived (PDF (Zipped)) from the original on 2021-11-03. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ^ "USB.org". USB.org. Archived from the original on 2012-06-19. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus 1.1 Specification" (PDF). cs.ucr.edu. 1998-09-23. pp. 150, 158. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-01-02. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus 2.0 Specification, Section 7.2.1.3 Low-power Bus-powered Functions" (ZIP). usb.org. 2000-04-27. Archived from the original on 2013-09-10. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus 2.0 Specification, Section 7.2.1.4 High-power Bus-powered Functions" (ZIP). usb.org. 2000-04-27. Archived from the original on 2013-09-10. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- ^ "Roundup: 2.5-inch Hard Disk Drives with 500 GB, 640 GB and 750 GB Storage Capacities (page 17)". xbitlabs.com. 2010-06-16. Archived from the original on 2010-06-28. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ^ "I have the drive plugged in but I cannot find the drive in "My Computer", why?". hitachigst.com. 2001-05-16. Archived from the original on 2011-02-15. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ "USB-IF Compliance Updates". Compliance.usb.org. 2011-09-01. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- ^ a b c d "Battery Charging Specification, Revision 1.2". USB Implementers Forum. 2012-03-15. Archived from the original on 2021-03-10. Retrieved 2021-08-13.

- ^ "Battery Charging Specification, Revision 1.1". USB Implementers Forum. 2009-04-15. Archived from the original on 2014-03-29. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ^ "Battery Charging v1.2 Spec and Adopters Agreement" (Zip). USB Implementers Forum. 2012-03-15. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- ^ a b "Minty Boost — The mysteries of Apple device charging". Lady Ada. 2011-05-17. Archived from the original on 2012-03-28.

- ^ "Modify a cheap USB charger to feed an iPod, iPhone". 2011-10-05. Archived from the original on 2011-10-07.

- ^ "About Apple USB power adaptors – Apple Support (AU)". Apple Support. Retrieved 2025-03-21.

- ^ "On an Apple 12W USB Charger, how are the D+ and D- lines configured?". Electrical Engineering Stack Exchange.

- ^ a b c "USB Power Delivery — Introduction" (PDF). 2012-07-16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-23. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- ^ a b "10 Power Rules", Universal Serial Bus Power Delivery Specification revision 2.0, version 1.2, USB Implementers Forum, 2016-03-25, archived from the original on 2024-05-26, retrieved 2016-04-09

- ^ a b "10 Power Rules", Universal Serial Bus Power Delivery Specification revision 3.0, version 1.1, USB Implementers Forum, archived from the original on 2024-05-26, retrieved 2017-09-05

- ^ a b c "10 Power Rules", Universal Serial Bus Power Delivery Specification revision 3.1, version 1.0, USB Implementers Forum, retrieved 2017-09-05

- ^ Burgess, Rick (2013-04-22). "USB 3.0 SuperSpeed Update to Eliminate Need for Chargers". TechSpot.

- ^ "USB 3.0 Promoter Group Announces Availability of USB Power Delivery Specification" (PDF). 2012-07-18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-01-20. Retrieved 2013-01-16.

- ^ "Edison's revenge". The Economist. 2013-10-19. Archived from the original on 2013-10-22. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ "USB Power Delivery".

- ^ "USB 3.1 Specification". Archived from the original on 2012-06-19. Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- ^ "USB Power Delivery v2.0 Specification Finalized - USB Gains Alternate Modes". AnandTech.com. Archived from the original on 2014-09-18.

- ^ "USB Future Specifications Industry Reviews" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-07-29. Retrieved 2014-08-10.

- ^ "A. Power Profiles". Universal Serial Bus Power Delivery Specification revision 2.0, version 1.2 (Technical report). USB Implementers Forum. 2016-03-25. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ^ "USB Power Delivery" (PDF). usb.org. USB-IF. 2016-10-20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20.

- ^ Waters, Deric (2016-07-14). "USB Power Delivery 2.0 vs 3.0". E2E.TI.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-30. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- ^ "USB-IF Introduces Fast Charging to Expand its Certified USB Charger Initiative" (Press release). 2018-01-09. Retrieved 2018-01-10.

- ^ USB-PD boosts USB-C power delivery to 240W at 48V. Nick Flaherty, EENews. May 28, 2021

- ^ USB-C Power Delivery Hits 240W with Extended Power Range. Ganesh T S, Anandtech. May 28, 2021

- ^ "Teardown of Brand New Apple 140W USB-C GaN Charger". 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- ^ a b "Framework Laptop 16 Deep Dive - 180W Power Adapter". Framework. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ Universal Serial Bus Power Delivery Specification revision 3.2, version 1.0, USB Implementers Forum, retrieved 2023-02-13

- ^ "How fast can a fast-charging phone charge if a fast-charging phone can charge really fast?". CNet. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ "Qualcomm Announces Quick Charge 4: Supports USB Type-C Power Delivery". AnandTech. Archived from the original on 2016-11-17. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ "Teardown of Anker 140W PD3.1 USB-C GaN Charger (717 Charger)". 2022-10-26.

- ^ 140W PD 3.1 Power Adapters, the future of USB C Power Delivery, 2023-01-02, retrieved 2024-03-08

- ^ "ThinkPad Ultra Dock". lenovo.com. Archived from the original on 2016-09-17. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- ^ "Toshiba NB200 User Manual" (PDF). UK. 2009-03-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-19. Retrieved 2014-01-26.

- ^ "USB PowerShare Feature". dell.com. 2019-09-15. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ^ "USB PowerShare Feature". dell.com. 2013-06-05. Archived from the original on 2013-11-08. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ^ "USB Sleep-and-Charge Ports". toshiba.com. Archived from the original on 2014-12-14. Retrieved 2014-12-21.

- ^ "USB Charge Manager". packardbell.com. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ^ "How to configure the system to charge devices over USB port when it is off - idea/Lenovo laptops - NL". support.lenovo.com. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Cai Yan (2007-05-31). "China to enforce universal cell phone charger". EE Times. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ^ The Chinese technical standard: "YD/T 1591-2006, Technical Requirements and Test Method of Charger and Interface for Mobile Telecommunication Terminal Equipment" (PDF). Dian yuan (in Chinese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-15.

- ^ Lam, Crystal; Liu, Harry (2007-10-22). "How to conform to China's new mobile phone interface standards". Wireless Net DesignLine. Archived from the original on 2014-05-14. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ^ "Pros Seem to Outdo Cons in New Phone Charger Standard". News.com. 2007-09-20. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- ^ "Broad Manufacturer Agreement Gives Universal Phone Cable Green Light" (Press release). OTMP. 2007-09-17. Archived from the original on 2009-06-29. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- ^ "Agreement on Mobile phone Standard Charger" (Press release). GSM World. Archived from the original on 2009-02-17.

- ^ "Common Charging and Local Data Connectivity". Open Mobile Terminal Platform. 2009-02-11. Archived from the original on 2009-03-29. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ^ "Universal Charging Solution ~ GSM World". GSM world. Archived from the original on 2010-06-26. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ^ "Meeting the challenge of the universal charge standard in mobile phones". Planet Analog. Archived from the original on 2012-09-09. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ^ "The Wireless Association Announces One Universal Charger Solution to Celebrate Earth Day" (Press release). CTIA. 2009-04-22. Archived from the original on 2010-12-14. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ^ "Universal Phone Charger Standard Approved" (Press release). ITU. 2009-10-22. Archived from the original on 2010-03-27. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ "chargers". EU: EC. 2009-06-29. Archived from the original on 2009-10-23. Retrieved 2010-06-22.