Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Underwater explosion

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

An underwater explosion (also known as an UNDEX) is a chemical or nuclear explosion that occurs under the surface of a body of water. While useful in anti-ship and submarine warfare, underwater bombs are not as effective against coastal facilities.[1]

Properties of water

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2025) |

Underwater explosions differ from in-air explosions due to the properties of water:

- Mass and incompressibility (all explosions) – water has a much higher density than air, which makes water harder to move (higher inertia). It is also relatively hard to compress (increase density) when under pressure in a low range (up to about 100 atmospheres). These two together make water an excellent conductor of shock waves from an explosion.

- Effect of neutron exposure on salt water (nuclear explosions only) – most underwater blast scenarios happen in seawater, not fresh or pure water. The water itself is not much affected by neutrons but salt is strongly affected. When exposed to neutron radiation during the microsecond of active detonation of a nuclear pit, water itself does not typically "activate", or become radioactive. The two elements in water, hydrogen and oxygen, can absorb an extra neutron, becoming deuterium and oxygen-17 respectively, both of which are stable isotopes. Even oxygen-18 is stable. Radioactive atoms can result if a hydrogen atom absorbs two neutrons, an oxygen atom absorbs three neutrons, or oxygen-16 undergoes a high energy neutron (n-p) reaction to produce a short-lived nitrogen-16. In any typical scenario, the probability of such multiple captures in significant numbers in the short time of active nuclear reactions around a bomb is very low. Salt in seawater readily absorbs neutrons into both the sodium-23 and chlorine-35 atoms, which change to radioactive isotopes. Sodium-24 has a half-life of about 15 hours, while that of chlorine-36 (which has a lower activation cross-section) is 300,000 years. The sodium is the most dangerous contaminant after the explosion because it has a short half-life.[2][self-published source?] These are generally the main radioactive contaminants in an underwater blast; others are the usual blend of irradiated minerals, coral, unused nuclear fuel, and bomb case components present in a surface blast nuclear fallout, carried in suspension or dissolved in the water. Distillation or evaporating water (clouds, humidity, and precipitation) removes radiation contamination, leaving behind the radioactive salts.

Effects

[edit]Effects of an underwater explosion depend on several things, including distance from the explosion, the energy of the explosion, the depth of the explosion, and the depth of the water.[3]

Underwater explosions are categorized by the depth of the explosion. Shallow underwater explosions are those where a crater formed at the water's surface is large in comparison with the depth of the explosion. Deep underwater explosions are those where the crater is small in comparison with the depth of the explosion,[3] or nonexistent.[citation needed]

The overall effect of an underwater explosion depends on depth, the size and nature of the explosive charge, and the presence, composition and distance of reflecting surfaces such as the seabed, surface, thermoclines, etc. This phenomenon has been extensively used in antiship warhead design since an underwater explosion (particularly one underneath a hull) can produce greater damage than an above-surface one of the same explosive size. Initial damage to a target will be caused by the first shockwave; this damage will be amplified by the subsequent physical movement of water and by the repeated secondary shockwaves or bubble pulse. Additionally, charge detonation away from the target can result in damage over a larger hull area.[4]

Underwater nuclear tests close to the surface can disperse radioactive water and steam over a large area, with severe effects on marine life, nearby infrastructures and humans.[5][6] The detonation of nuclear weapons underwater was banned by the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and it is also prohibited under the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty of 1996.[citation needed]

Shallow underwater explosion

[edit]

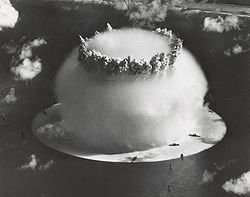

The Baker nuclear test at Bikini Atoll in July 1946 was a shallow underwater explosion, part of Operation Crossroads. A 20 kiloton warhead was detonated in a lagoon which was approximately 200 ft (61 m) deep. The first effect was illumination of the sea from the underwater fireball. A rapidly expanding gas bubble created a shock wave that caused an expanding ring of apparently dark water at the surface, called the slick, followed by an expanding ring of apparently white water, called the crack. A mound of water and spray, called the spray dome, formed at the water's surface which became more columnar as it rose. When the rising gas bubble broke the surface, it created a shock wave in the air as well. Water vapor in the air condensed as a result of Prandtl–Meyer expansion fans decreasing the air pressure, density, and temperature below the dew point; making a spherical cloud that marked the location of the shock wave. Water filling the cavity formed by the bubble caused a hollow column of water, called the chimney or plume, to rise 6,000 ft (1,800 m) in the air and break through the top of the cloud. A series of ocean surface waves moved outward from the center. The first wave was about 94 ft (29 m) high at 1,000 ft (300 m) from the center. Other waves followed, and at further distances some of these were higher than the first wave. For example, at 22,000 ft (6,700 m) from the center, the ninth wave was the highest at 6 ft (1.8 m). Gravity caused the column to fall to the surface and caused a cloud of mist to move outward rapidly from the base of the column, called the base surge. The ultimate size of the base surge was 3.5 mi (5.6 km) in diameter and 1,800 ft (550 m) high. The base surge rose from the surface and merged with other products of the explosion, to form clouds which produced moderate to heavy rainfall for nearly one hour.[7]

Deep underwater explosion

[edit]

An example of a deep underwater explosion is the Wahoo test, which was carried out in 1958 as part of Operation Hardtack I. A 9 kt Mk-7 was detonated at a depth of 500 ft (150 m) in deep water. There was little evidence of a fireball. The spray dome rose to a height of 900 ft (270 m). Gas from the bubble broke through the spray dome to form jets which shot out in all directions and reached heights of up to 1,700 ft (520 m). The base surge at its maximum size was 2.5 mi (4.0 km) in diameter and 1,000 ft (300 m) high.[7]

The heights of surface waves generated by deep underwater explosions are greater because more energy is delivered to the water. During the Cold War, underwater explosions were thought to operate under the same principles as tsunamis, potentially increasing dramatically in height as they move over shallow water, and flooding the land beyond the shoreline.[8] Later research and analysis suggested that water waves generated by explosions were different from those generated by tsunamis and landslides. Méhauté et al. conclude in their 1996 overview Water Waves Generated by Underwater Explosion that the surface waves from even a very large offshore undersea explosion would expend most of their energy on the continental shelf, resulting in coastal flooding no worse than that from a bad storm.[3]

The Operation Wigwam test in 1955 occurred at a depth of 2,000 ft (610 m), the deepest detonation of any nuclear device.

Deep nuclear explosion

[edit]

Source:[9]

Unless it breaks the water surface while still a hot gas bubble, an underwater nuclear explosion leaves no trace at the surface but hot, radioactive water rising from below. This is the case with explosions deeper than about 2,000 ft (610 m), within the parameters of historic test yields.[7]

About one second after such an explosion, the hot gas bubble collapses because:

- The water pressure is enormous below 2,000 feet (610 m).

- The expansion reduces gas pressure, which decreases temperature.

- Rayleigh–Taylor instability at the gas/water boundary causes "fingers" of water to extend into the bubble, increasing the boundary surface area.

- Water is nearly incompressible.

- Vast amounts of energy are absorbed by phase change (water becomes steam at the fireball boundary).

- Expansion quickly becomes unsustainable because the amount of water pushed outward increases with the cube of the blast-bubble radius.

Since water is not readily compressible, moving this much of it out of the way so quickly absorbs a massive amount of energy—all of which comes from the pressure inside the expanding bubble. Water pressure outside the bubble soon causes it to collapse back into a small sphere and rebound, expanding again. This is repeated several times, but each rebound contains only about 40% of the energy of the previous cycle.

At the maximum diameter of the first oscillation, a very large nuclear bomb exploded in very deep water creates a bubble about a half-mile (800 m) wide in about one second and then contracts, which also takes about a second. Blast bubbles from deep nuclear explosions have slightly longer oscillations than shallow ones. They stop oscillating and become mere hot water in about six seconds. This happens sooner in nuclear blasts than bubbles from conventional explosives.

The water pressure of a deep explosion prevents any bubbles from surviving to float up to the surface.

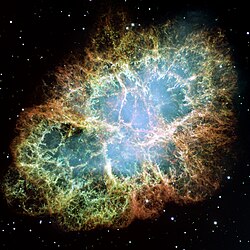

The drastic 60% loss of energy between oscillation cycles is caused in part by the extreme force of a nuclear explosion pushing the bubble wall outward supersonically (faster than the speed of sound in saltwater). This causes Rayleigh–Taylor instability. That is, the smooth water wall touching the blast face becomes turbulent and fractal, with fingers and branches of cold ocean water extending into the bubble. That cold water cools the hot gas inside and causes it to condense. The bubble becomes less of a sphere and looks more like the Crab Nebula—the deviation of which from a smooth surface is also due to Rayleigh–Taylor instability as ejected stellar material pushes through the interstellar medium.

As might be expected, large, shallow explosions expand faster than deep, small ones.

Despite being in direct contact with a nuclear explosion fireball, the water in the expanding bubble wall does not boil; the pressure inside the bubble exceeds (by far) the vapor pressure of water. The water touching the blast can only boil during bubble contraction. This boiling is like evaporation, cooling the bubble wall, and is another reason that an oscillating blast bubble loses most of the energy it had in the previous cycle.

During these hot gas oscillations, the bubble continually rises for the same reason a mushroom cloud does: it is less dense. This causes the blast bubble never to be perfectly spherical. Instead, the bottom of the bubble is flatter, and during contraction, it even tends to "reach up" toward the blast center.

In the last expansion cycle, the bottom of the bubble touches the top before the sides have fully collapsed, and the bubble becomes a torus in its last second of life. About six seconds after detonation, all that remains of a large, deep nuclear explosion is a column of hot water rising and cooling in the near-freezing ocean.

List of underwater nuclear tests

[edit]Relatively few underwater nuclear tests were performed before they were banned by the Partial Test Ban Treaty. They were:

| Test series | Name | Nation | Date (UT) | Location | Bomb depth | Depth of water | Yield | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crossroads | Baker | US | July 25, 1946 | Bikini Atoll, PPG | 50 m (160 ft) | 100 m (330 ft) | 20 kt | Probe the effects of a shallow underwater nuclear bomb on various surface fleet units |

| Hurricane | Hurricane | UK | October 2, 1952 | Monte Bello Islands | 2.7 m (8 ft 10 in) | 12 m (39 ft) | 25 kt | First British nuclear test. Nuclear effects test of a ship-smuggled nuclear bomb at a port |

| Wigwam | Wigwam | US | May 14, 1955 | North Pacific Ocean | 610 m (2,000 ft) | 4,880 m (16,010 ft) | 30 kt | A Mark 90-B7 "Betty" nuclear depth charge test to determine specifically submarine vulnerability to deep atomic depth charges |

| 1955 | 22 (Joe 17) | USSR | September 21, 1955 | Chernaya Bay, Novaya Zemlya | 10 m (33 ft) | Unknown | 3.5 kt | Test of a nuclear torpedo |

| 1957 | 48 | USSR | October 10, 1957 | Novaya Zemlya | 30 m (98 ft) | Unknown | 6 kt | A T-5 torpedo test |

| Hardtack I | Wahoo | US | May 16, 1958 | Outside Enewetak Atoll, PPG | 150 m (490 ft) | 980 m (3,220 ft) | 9 kt | Test of a deep water bomb against ship hulls |

| Hardtack I | Umbrella | US | June 8, 1958 | Inside Enewetak Atoll, PPG | 46 m (151 ft) | 46 m (151 ft) | 9 kt | Test of a shallow water bomb on ocean floor against ship hulls |

| 1961 | 122 (Korall-1) | USSR | October 23, 1961 | Novaya Zemlya | 20 m (66 ft) | Unknown | 4.8 kt | A T-5 torpedo test |

| Dominic | Swordfish | US | May 11, 1962 | Pacific Ocean, near Johnston Island | 198 m (650 ft) | 1,000 m (3,300 ft) | <20 kt | Test of the RUR-5 ASROC system |

Note: it is often believed that the French did extensive underwater tests in French West Polynesia on the Moruroa and Fangataufa Atolls. This is incorrect; the bombs were placed in shafts drilled into the underlying coral and volcanic rock, and they did not intentionally leak fallout.

Nuclear Test Gallery

[edit]Nuclear detonation detection via hydroacoustics

[edit]There are several methods of detecting nuclear detonations. Hydroacoustics is the primary means of determining if a nuclear detonation has occurred underwater. Hydrophones are used to monitor the change in water pressure as sound waves propagate through the world's oceans.[10] Sound travels through 20 °C water at approximately 1482 meters per second, compared to the 332 m/s speed of sound through air.[11][12] In the world's oceans, sound travels most efficiently at a depth of approximately 1000 meters. Sound waves that travel at this depth travel at minimum speed and are trapped in a layer known as the Sound Fixing and Ranging Channel (SOFAR).[10] Sounds can be detected in the SOFAR from large distances, allowing for a limited number of monitoring stations required to detect oceanic activity. Hydroacoustics was originally developed in the early 20th century as a means of detecting objects like icebergs and shoals to prevent accidents at sea.[10]

Three hydroacoustic stations were built before the adoption of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. Two hydrophone stations were built in the North Pacific Ocean and Mid-Atlantic Ocean, and a T-phase[clarification needed] station was built off the west coast of Canada. When the CTBT was adopted, 8 more hydroacoustic stations were constructed to create a comprehensive network capable of identifying underwater nuclear detonations anywhere in the world.[13] These 11 hydroacoustic stations, in addition to 326 monitoring stations and laboratories, comprise the International Monitoring System (IMS), which is monitored by the Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO).[14]

There are two types of hydroacoustic stations currently used in the IMS network; 6 hydrophone monitoring stations and 5 T-phase stations. These 11 stations are primarily located in the southern hemisphere, which is primarily ocean.[15] Hydrophone monitoring stations consist of an array of three hydrophones suspended from cables tethered to the ocean floor. They are positioned at a depth located within the SOFAR in order to effectively gather readings.[13] Each hydrophone records 250 samples per second, while the tethering cable supplies power and carries information to the shore.[13] This information is converted to a usable form and transmitted via secure satellite link to other facilities for analysis. T-phase monitoring stations record seismic signals generate from sound waves that have coupled with the ocean floor or shoreline.[16] T-phase stations are generally located on steep-sloped islands in order to gather the cleanest possible seismic readings.[15] Like hydrophone stations, this information is sent to the shore and transmitted via satellite link for further analysis.[16] Hydrophone stations have the benefit of gathering readings directly from the SOFAR, but are generally more expensive to implement than T-phase stations.[16] Hydroacoustic stations monitor frequencies from 1 to 100 Hertz to determine if an underwater detonation has occurred. If a potential detonation has been identified by one or more stations, the gathered signals will contain a high bandwidth with the frequency spectrum indicating an underwater cavity at the source.[16]

See also

[edit]Sources

[edit]- ^ Zhang, Ruiyao; Xiao, Wei; Yao, Xiongliang; Zou, Xiaochao (2025-04-01). "Review of Research on Underwater Explosions Related to Ship Damage and Stability". Journal of Marine Science and Application. 24 (2): 285–300. doi:10.1007/s11804-025-00633-4. ISSN 1993-5048.

- ^ Sobel, Michael I. "Nuclear Waste (class notes)". CUNY Brooklyn College, Physics Department. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ a b c Le Méhauté, Bernard; Wang, Shen (1995). Water waves generated by underwater explosion (PDF). World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 981-02-2083-9. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019.

- ^ RMCS Precis on Naval Ammunition, Jan 91

- ^ "'Test Baker', Bikini Atoll". CTBTO Preparatory Commission. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Is it possible to test a nuclear weapon without producing radioactive fallout?". How stuff works. 11 October 2006. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ a b c Glasstone, Samuel; Dolan, Philip (1977). "Descriptions of nuclear explosions". The effects of nuclear weapons (Third ed.). Washington: U.S. Department of Defense; Energy Research and Development Administration.

- ^ Glasstone, Samuel; Dolan, Philip (1977). "Shock effects of surface and subsurface bursts". The effects of nuclear weapons (third ed.). Washington: U.S. Department of Defense; Energy Research and Development Administration.

- ^ All the information in this section is directly from the now-declassified Analysis of various models of underwater nuclear explosions (1971), U.S. Department of Defense

- ^ a b c "Hydroacoustic monitoring: CTBTO Preparatory Commission". www.ctbto.org. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ^ "How fast does sound travel?". www.indiana.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ^ "Untitled Document". www.le.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ^ a b c Australia, c\=AU\;o\=Australia Government\;ou\=Geoscience (2014-05-15). "Hydroacoustic Monitoring". www.ga.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Overview of the verification regime: CTBTO Preparatory Commission". www.ctbto.org. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ^ a b "ASA/EAA/DAGA '99 - Hydroacoustic Monitoring for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty". acoustics.org. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- ^ a b c d Monitoring, Government of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Nuclear Explosion. "IMS Hydroacoustic Network". can-ndc.nrcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

[edit]- Glasstone, Samuel; Dolan, Philip (1977). The effects of nuclear weapons (third ed.). Washington: U.S. Department of Defense; Energy Research and Development Administration.

- Le Méhauté, Bernard; Wang, Shen (1995). Water waves generated by underwater explosion (PDF). Advanced Series on Ocean Engineering. Vol. 10. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 981-02-2083-9. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019.