Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

String vibration

View on Wikipedia

A vibration in a string is a wave. Initial disturbance (such as plucking or striking) causes a vibrating string to produce a sound with constant frequency, i.e., constant pitch. The nature of this frequency selection process occurs for a stretched string with a finite length, which means that only particular frequencies can survive on this string. If the length, tension, and linear density (e.g., the thickness or material choices) of the string are correctly specified, the sound produced is a musical tone. Vibrating strings are the basis of string instruments such as guitars, cellos, and pianos. For a homogeneous string, the motion is given by the wave equation.

Wave

[edit]The velocity of propagation of a wave in a string () is proportional to the square root of the force of tension of the string () and inversely proportional to the square root of the linear density () of the string:

This relationship was discovered by Vincenzo Galilei in the late 1500s. [citation needed]

Derivation

[edit]

Source:[1]

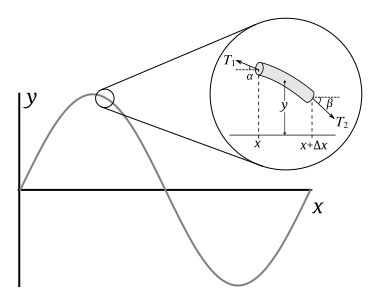

Let be the length of a piece of string, its mass, and its linear density. If angles and are small, then the horizontal components of tension on either side can both be approximated by a constant , for which the net horizontal force is zero. Accordingly, using the small angle approximation, the horizontal tensions acting on both sides of the string segment are given by

From Newton's second law for the vertical component, the mass (which is the product of its linear density and length) of this piece times its acceleration, , will be equal to the net force on the piece:

Dividing this expression by and substituting the first and second equations obtains (we can choose either the first or the second equation for , so we conveniently choose each one with the matching angle and )

According to the small-angle approximation, the tangents of the angles at the ends of the string piece are equal to the slopes at the ends, with an additional minus sign due to the definition of and . Using this fact and rearranging provides

In the limit that approaches zero, the left hand side is the definition of the second derivative of ,

this equation is known as the wave equation, and the coefficient of the second time derivative term is equal to ; thus

Where is the speed of propagation of the wave in the string. However, this derivation is only valid for small amplitude vibrations; for those of large amplitude, is not a good approximation for the length of the string piece, the horizontal component of tension is not necessarily constant. The horizontal tensions are not well approximated by .

Frequency of the wave

[edit]Once the speed of propagation is known, the frequency of the sound produced by the string can be calculated. The speed of propagation of a wave is equal to the wavelength divided by the period , or multiplied by the frequency :

If the length of the string is , the fundamental harmonic is the one produced by the vibration whose nodes are the two ends of the string, so is half of the wavelength of the fundamental harmonic. Hence one obtains Mersenne's laws:

where is the tension (in Newtons), is the linear density (that is, the mass per unit length), and is the length of the vibrating part of the string. Therefore:

- the shorter the string, the higher the frequency of the fundamental

- the higher the tension, the higher the frequency of the fundamental

- the lighter the string, the higher the frequency of the fundamental

Moreover, if we take the nth harmonic as having a wavelength given by , then we easily get an expression for the frequency of the nth harmonic:

And for a string under a tension T with linear density , then

Observing string vibrations

[edit]One can see the waveforms on a vibrating string if the frequency is low enough and the vibrating string is held in front of a CRT screen such as one of a television or a computer (not of an analog oscilloscope). This effect is called the stroboscopic effect, and the rate at which the string seems to vibrate is the difference between the frequency of the string and the refresh rate of the screen. The same can happen with a fluorescent lamp, at a rate that is the difference between the frequency of the string and the frequency of the alternating current. (If the refresh rate of the screen equals the frequency of the string or an integer multiple thereof, the string will appear still but deformed.) In daylight and other non-oscillating light sources, this effect does not occur and the string appears still but thicker, and lighter or blurred, due to persistence of vision.

A similar but more controllable effect can be obtained using a stroboscope. This device allows matching the frequency of the xenon flash lamp to the frequency of vibration of the string. In a dark room, this clearly shows the waveform. Otherwise, one can use bending or, perhaps more easily, by adjusting the machine heads, to obtain the same, or a multiple, of the AC frequency to achieve the same effect. For example, in the case of a guitar, the 6th (lowest pitched) string pressed to the third fret gives a G at 97.999 Hz. A slight adjustment can alter it to 100 Hz, exactly one octave above the alternating current frequency in Europe and most countries in Africa and Asia, 50 Hz. In most countries of the Americas—where the AC frequency is 60 Hz—altering A# on the fifth string, first fret from 116.54 Hz to 120 Hz produces a similar effect.

See also

[edit]- Fretted instruments

- Musical acoustics

- Vibrations of a circular drum

- Melde's experiment

- 3rd bridge (harmonic resonance based on equal string divisions)

- String resonance

- Reflection phase change

- Hilbert space

References

[edit]- Molteno, T. C. A.; N. B. Tufillaro (September 2004). "An experimental investigation into the dynamics of a string". American Journal of Physics. 72 (9): 1157–1169. Bibcode:2004AmJPh..72.1157M. doi:10.1119/1.1764557.

- Tufillaro, N. B. (1989). "Nonlinear and chaotic string vibrations". American Journal of Physics. 57 (5): 408. Bibcode:1989AmJPh..57..408T. doi:10.1119/1.16011.

- Specific

External links

[edit]- "The Vibrating String" by Alain Goriely and Mark Robertson-Tessi, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

String vibration

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of String Waves

Transverse Wave Motion

In transverse waves on a string, the particles of the medium oscillate perpendicular to the direction of wave propagation, resulting in a displacement that is vertical or horizontal relative to the string's length.[4] This perpendicular motion distinguishes transverse waves from longitudinal waves, where particle displacement aligns with the propagation direction.[5] Waves on a string are typically initiated by plucking, which displaces a portion of the string transversely, or by bowing, which applies frictional force to sustain oscillation and propagate the disturbance along the string. Once initiated, the disturbance travels as a series of connected oscillations, with each segment of the string passing the motion to its neighbors through tension forces. The propagation relies on the string's tension, which provides the restoring force, and its linear density, the mass per unit length; qualitatively, waves propagate faster on highly taut strings with low linear density, as the reduced inertia allows quicker response to tension.[6] The energy carried by these transverse waves alternates between kinetic energy, arising from the transverse velocity of string particles, and potential energy, stored in the slight stretching of the string beyond its equilibrium length under tension.[7] This energy transfer occurs without net displacement of the string material along the propagation direction, conserving the wave's form as it moves.[8] Early observations of string vibrations trace back to Pythagoras around 500 BCE, who experimented with a monochord—a single-string instrument—to relate vibrating string lengths to musical harmonies, laying foundational insights into wave behavior in musical contexts.[9] These experiments highlighted how transverse vibrations produce audible tones, influencing later studies in acoustics and wave physics.[10]Factors Influencing Wave Propagation

The linear mass density, denoted as μ and defined as the mass per unit length of the string, plays a crucial role in determining the speed of wave propagation, with higher values of μ leading to slower wave speeds due to increased inertia resisting the motion.[11] This inverse relationship arises because denser strings require more force to accelerate segments during vibration, thereby reducing the overall propagation velocity.[12] Tension, represented as T, serves as the primary restoring force in string vibrations, pulling displaced segments back toward equilibrium and directly influencing wave speed.[13] Increasing the tension, such as by tightening a string, accelerates the restoring action, resulting in faster wave propagation; for instance, doubling the tension can increase the speed proportionally to the square root of two.[11] The combined influence of tension and linear mass density governs wave speed through a qualitative scaling proportional to the square root of T/μ, where higher tension boosts speed while greater density diminishes it.[12] In practical applications like guitar strings, this scaling explains why thin, high-tension strings produce faster waves and higher pitches compared to thicker, looser ones, allowing musicians to tune instruments by adjusting tension to alter propagation characteristics.[1] Damping mechanisms, including air resistance and internal friction within the string material, cause the wave amplitude to decay exponentially over distance, dissipating energy and limiting propagation.[13] Air damping arises from viscous drag on the oscillating string, while internal friction involves material hysteresis that converts vibrational energy to heat, with both effects more pronounced in higher-frequency modes.[13] Environmental factors further modulate wave propagation, with temperature affecting the string's elasticity through changes in Young's modulus, which can alter tension and damping rates in fixed-length setups.[13] Gravity plays a minor role, primarily negligible in horizontal taut strings where tension dominates, though in horizontal configurations it may introduce slight sagging that subtly impacts equilibrium shape, and in vertical configurations it creates a tension gradient along the length, without significantly altering speed.[14][15]Mathematical Modeling

Derivation of the Wave Equation

The derivation of the wave equation for string vibrations begins with key assumptions about the physical system. The string is modeled as uniform and flexible, with constant linear mass density (mass per unit length) and under constant tension , while neglecting gravity and friction. Transverse displacements are assumed to be small, allowing a linear approximation where the tension direction remains nearly horizontal and the string's length does not change significantly.[16] To derive the equation, consider a small segment of the string between positions and at time , with transverse displacement . The net transverse force on this segment arises from the difference in the vertical components of tension at its ends. The slope at is , and at it is . For small angles, the vertical force components are approximately at (downward if positive) and at (upward). The net upward force is thus . By Newton's second law, this equals the mass of the segment times its transverse acceleration . Dividing by and taking the limit as yields the one-dimensional wave equation: Here, represents the transverse displacement as a function of position and time ; the second spatial derivative captures the curvature of the string, which determines the restoring force, while the second temporal derivative represents the acceleration of the segment. The coefficient defines the square of the wave speed , where higher tension increases speed and higher density decreases it.[16][17] This equation predicts non-dispersive waves, meaning the propagation speed is constant and independent of frequency or wavelength, allowing arbitrary wave shapes to travel without distortion. Solutions of the form represent right- and left-propagating waves, respectively, confirming uniform speed for all components.[16] The linear wave equation has limitations, as it neglects longitudinal waves along the string and assumes small amplitudes where nonlinear effects—such as amplitude-dependent tension variations or geometric stiffening—do not arise. For large displacements, these nonlinearities lead to coupled equations for transverse and longitudinal motion, altering wave behavior.[18]Standing Waves and Boundary Conditions

The general solution to the one-dimensional wave equation describing transverse vibrations on a string consists of the superposition of two arbitrary traveling waves propagating in opposite directions along the string:where represents a wave traveling to the right, a wave to the left, and is the speed of propagation determined by the string's tension and linear mass density.[19] This form arises from the linearity of the wave equation, allowing any solution to be decomposed into forward and backward components.[20] Standing waves emerge on a finite string when an incident traveling wave reflects from the boundaries and superposes with the reflected wave, resulting in a stationary interference pattern where the shape of the wave does not propagate but oscillates in place.[21] For a string of length fixed at both ends, the boundary conditions impose and for all times , ensuring zero transverse displacement at these points.[19] These constraints quantize the possible wave patterns, yielding sinusoidal spatial modes of the form for positive integers , which satisfy the boundary conditions exactly.[20] The full standing wave solution for the -th mode is then

where is the mode amplitude, the angular frequency, and a phase constant.[19] In these standing wave modes, nodes—points of zero displacement—occur at the fixed ends ( and ) and at intermediate positions for integers , dividing the string into equal segments.[21] Antinodes, where the displacement reaches maximum amplitude, are located midway between consecutive nodes; for the fundamental mode (), this occurs at the string's center ().[19] Higher modes feature more nodes and antinodes, creating increasingly complex spatial patterns while maintaining the boundary-imposed zeros.[20] The standing wave solutions correspond to normal modes of vibration, which are orthogonal in the spatial domain because the functions form a complete orthogonal set over the interval .[19] This orthogonality ensures that each mode can be excited independently, with vibrations in one mode not coupling to others under free evolution.[20] The temporal evolution of each mode is purely harmonic, governed by the cosine term with its associated frequency and phase.[21] Due to the linearity and orthogonality of the normal modes, the total energy of the string's vibration is distributed among the modes such that each mode's energy remains constant over time, with no exchange between modes absent external perturbations like driving forces.[19] This modal energy conservation arises from the absence of nonlinear terms in the wave equation, preserving the integrity of individual mode contributions to the overall motion.[20]