Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Combination tone

View on Wikipedia

A combination tone (also called resultant tone or subjective tone)[2] is a psychoacoustic and sometimes physical phenomenon of an additional tone or tones that are perceived when two real tones are sounded at the same time. Their discovery is credited to the violinist Giuseppe Tartini,[3] so they are also called Tartini tones. He reported in 1754 that he heard it already in 1714.[4]

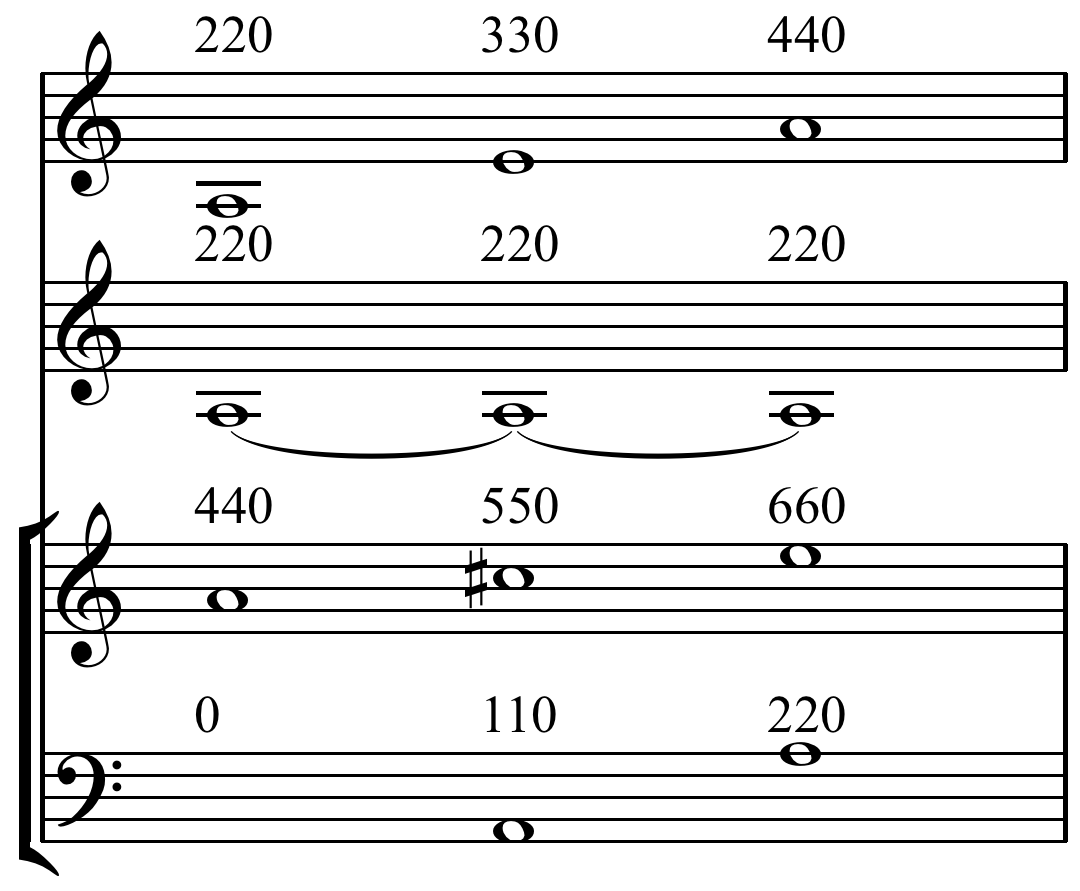

There are two types of combination tones: sum tones whose frequencies are found by adding the frequencies of the real tones, and difference tones whose frequencies are the difference between the frequencies of the real tones. "Combination tones are heard when two pure tones (i.e., tones produced by simple harmonic sound waves having no overtones), differing in frequency by about 50 cycles per second [Hertz] or more, sound together at sufficient intensity."[2]

Combination tones can also be produced electronically by combining two signals in a circuit that has nonlinear distortion, such as an amplifier subject to clipping or a ring modulator.

Explanation

[edit]One way a difference tone can be heard is when two tones with fairly complete sets of harmonics make a just fifth. This can be explained as an example of the missing fundamental phenomenon.[5] If is the missing fundamental frequency, then would be the frequency of the lower tone, and its harmonics would be etc. Since a fifth corresponds to a frequency ratio of 2:3, the higher tone and its harmonics would then be etc. When both tones are sounded, there are components with frequencies of etc. The missing fundamental is heard because so many of these components refer to it.

For some time, during the 19th century it was explained by Lagrange, Chladni, and Young as a form of acoustic beats. This was incorrect.[6]: 20

The specific phenomenon that Tartini discovered was physical. Sum and difference tones are thought to be caused sometimes by the non-linearity of the inner ear. This causes intermodulation distortion of the various frequencies which enter the ear. They are combined linearly, generating relatively faint components with frequencies equal to the sums and differences of whole multiples of the original frequencies. Any components which are heard are usually lower, with the most commonly heard frequency being just the difference tone, , though this may be a consequence of the other phenomena. Although much less common, the following frequencies may also be heard:

For a time it was thought that the inner ear was solely responsible whenever a sum or difference tone was heard. However, experiments show evidence that even when using headphones providing a single pure tone to each ear separately, listeners may still hear a difference tone[citation needed]. Since the peculiar non-linear physics of the ear doesn't come into play in this case, it is thought that this must be a separate, neural phenomenon. Compare binaural beats.

Heinz Bohlen proposed what is now known as the Bohlen–Pierce scale on the basis of combination tones,[7] as well as the 833 cents scale.

Resultant tone

[edit]A resultant tone is "produced when any two loud and sustained musical sounds are heard at the same time."[8]

In pipe organs,[9] this is done by having two pipes, one pipe of the note being played, and another harmonically related, typically at its fifth, being sounded at the same time. The result is a pitch at a common subharmonic of the pitches played (one octave below the first pitch when the second is the fifth, 3:2, two octaves below when the second is the major third, 5:4). This effect is useful especially in the lowest ranks of the pipe organ where cost or space could prohibit having a rank of such low pitch. For example, a 32' pipe would be costly and take up as much as 16' of vertical space (if capped) or more commonly 17-32' (if open-ended) for each pipe. Using a resultant tone for such low pitches reduces the cost and space factor, but does not sound as full as a true 32' pipe. The effect can be enhanced by using further ranks in the harmonic series of the desired resultant tone.

This effect is most often used in the lowest octave of the organ only. It can vary from highly effective to disappointing depending on several factors, primarily the skill of the organ voicer, and the acoustics of the room the instrument is installed in.

It is possible to produce a melody with resultant tones from multiple harmonics played by two or more instruments. There is an example with seven saxophones.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Benade, Arthur H. (2014). Horns, Strings, and Harmony, p.83. Courier, Dover Books on Music. ISBN 9780486173597.

- ^ a b "Combination Tone", Britannica.com. Accessed September 2015.

- ^ "Tartini, Giuseppe". Enciclopedia Italiana. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Tartini, G. (1754). Trattato di Musica [Treatise on Music] (in Italian). Padua.

- ^ Beament, James (2001). How We Hear Music, p.81-2. The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-813-7.

- ^ Beyer, Robert T. (1999). Sounds of our times: two hundred years of acoustics. New York: AIP Press. ISBN 978-0-387-98435-3.

- ^ Max V. Mathews and John R. Pierce (1989). "The Bohlen–Pierce Scale", p.167. Current Directions in Computer Music Research, Max V. Mathews and John R. Pierce, eds. MIT Press.

- ^ Maitland, J. A. Fuller; ed. (1909). Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Volume 4, p.76. Macmillan. [ISBN unspecified].

- ^ James Ingall Wedgwood (1907). A Comprehensive Dictionary of Organ Stops: English and foreign, ancient and modern: practical, theoretical, historical, aesthetic, etymological, phonetic (2nd ed.). G. Schirmer. p. 1.

Further reading

[edit]- Adrianus J. M. Houtsma, Julius L. Goldstein, "Percepetion of Musical Intervals: Evidence for the Central Origin of the Pitch of Complex Tones", Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Research Laboratory of Electronics, Technical Report 484, October 1, 1971.

- Adrian Wehlte, Trios for Two, Practice book with combination tones for two flutes or two recorders – Explanation and examples, Edition Floeno 2020, ISMN 979-0-9000114-2-8

External links

[edit]- Titchener Difference Tones Training

- Difference tones on the harmonica

- Pitch Perception Lecture Notes

- Tartini computer program. Archived 2013-06-23 at the Wayback Machine Uses combination tones for pitch recognition. If certain intervals are played in double-stop, the program can display its Tartini-tone.

- http://www.organstops.org/r/Resultant.html

Combination tone

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Overview

What Are Combination Tones?

A combination tone is a psychoacoustic phenomenon in which one or more additional tones, not physically present in the sound source, are perceived by the listener when two or more real tones are sounded simultaneously.[1] These perceived tones arise due to nonlinear distortion processes within the auditory system.[9] A basic example occurs when two high-pitched pure tones are played loudly together, such as 1500 Hz and 2000 Hz, resulting in the perception of a lower-pitched 500 Hz tone that is the difference between the two primaries.[10] This additional tone can be heard as a steady pitch amid the originals, particularly when the primary tones are simple sine waves without complex harmonics.[1] Perception of combination tones generally requires sufficient intensity of the primary tones, typically above 50–60 dB SPL, as lower levels may not produce the necessary distortion for the effect to become audible.[1] The phenomenon is more prominent with pure tones or those having simple harmonic structures, where the auditory system's nonlinear response generates the subjective pitches without external sound waves at those frequencies. Combination tones are distinct from physical beats, which involve amplitude modulation and produce pulsating volume changes rather than steady pitches; beats are more noticeable at lower intensities, while combination tones emerge predominantly at higher levels.[1]Psychoacoustic Nature

Combination tones are a psychoacoustic phenomenon arising solely from the processing within the human auditory system, particularly the cochlea, where nonlinear interactions between primary tones generate perceived frequencies that are not present as distinct components in the external sound wave. These subjective tones, also known as resultant or ghost tones, emerge internally through cochlear amplification mechanisms and neural interpretation, without measurable propagation in the air as separate acoustic signals.[11][12] In auditory perception, combination tones play a key role in shaping the timbre of complex sounds by enriching the internal spectral representation, and they influence judgments of consonance and dissonance; for instance, the presence of certain combination tones between partials can introduce roughness, contributing to perceptions of dissonance in musical intervals. Difference tones, the most common type, are particularly prominent in such evaluations.[13] Experimental demonstrations of combination tones typically involve presenting two pure sine waves of different frequencies (e.g., via signal generators or audio software) at moderate to high intensities, where listeners report perceiving an additional tone corresponding to a frequency combination like the difference between the primaries; this confirms the perceptual origin, as microphone recordings of the stimulus reveal no such extra frequency in the acoustic signal. Behavioral psychoacoustic methods, such as masking paradigms, further quantify detection thresholds by having participants adjust a probe tone to cancel the perceived combination tone.[14] The audibility of combination tones varies with individual hearing sensitivity, as differences in cochlear health affect the nonlinear distortion processes;[14] age-related hearing loss, which often impairs high-frequency detection and cochlear amplification, can diminish their prominence.[15] Combination tones contribute to consonance perceptions in musical intervals such as octaves (2:1) and perfect fifths (3:2), where the resulting tones often align with the harmonic series.[13]Historical Development

Discovery by Tartini

In 1714, Italian violinist and composer Giuseppe Tartini (1692–1770) discovered an additional tone while practicing double stops on the violin, perceiving a faint lower pitch that accompanied the two higher notes being played simultaneously. This "terzo suono," or third sound, emerged as a subtle harmonic element, primarily manifesting as a difference tone derived from the frequencies of the primary notes.[16] Tartini documented his observations in detail in his 1754 treatise Trattato di musica secondo la vera scienza dell'armonia, where he described the terzo suono as an integral part of musical harmony arising from the interaction of simultaneous tones.[17] In the work, he conducted experiments, such as playing dyads on a single violin or distributing the notes between two violins, consistently hearing the third tone in both setups, which suggested its perceptual rather than purely instrumental nature. Tartini integrated this phenomenon into his theoretical framework, linking it to mathematical ratios and the principles of just intonation to explain consonant intervals. Tartini applied the terzo suono practically to refine violin tuning and performance, employing it as a diagnostic tool to achieve precise intonation for intervals such as the perfect third and fifth.[16] By listening for the clarity and stability of the third sound, musicians could adjust pitches to align with natural harmonic proportions, enhancing the purity of ensemble playing and solo execution. However, Tartini's understanding remained rooted in 18th-century musical theory, attributing the effect to fundamental laws of harmony without recognizing its psychoacoustic origin in auditory perception. Tartini's discovery sparked extensive debates among musicians and scientists throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries. Mathematicians like Leonhard Euler proposed physical explanations based on the interactions of sound waves, while physicist Thomas Young advanced a beat theory attributing combination tones to interference patterns rather than new frequencies.[5][18] These early theories laid groundwork for later physiological models, though they often viewed the tones as objective acoustic phenomena.Helmholtz's Contributions

In his seminal work On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music (original German: Die Lehre von den Tonempfindungen), first published in 1863 and building upon his earlier 1856 paper "Ueber Combinationstöne," German physicist and physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894) provided the first systematic scientific analysis of combination tones.[19] Helmholtz employed tuning forks driven by electromagnets to generate pure simple tones free of upper partials, often amplifying them through resonance chambers or tubes fitted to the ear for enhanced clarity.[19] By sounding two such tones simultaneously at moderate to high intensities, he elicited combination tones, which he isolated using additional resonators tuned to the expected frequencies of these emergent sounds, thereby confirming their presence through sympathetic reinforcement and beats.[19] These experiments demonstrated that combination tones were not artifacts of the sound source but subjective auditory phenomena perceptible only to the listener.[19] Helmholtz theorized that combination tones originate from nonlinear interactions within the inner ear, particularly along the cochlea's basilar membrane, where large-amplitude vibrations cause the mechanical response to deviate from simple harmonic motion.[19] He argued that this nonlinearity—arising from the asymmetric structure and sympathetic vibrations of the basilar membrane and the organs of Corti—generates new frequencies, such as difference and summation tones, as the ear decomposes complex sounds into their components per Ohm's acoustic law.[19] Unlike prior views attributing these tones to external air vibrations or the outer ear, Helmholtz's model emphasized physiological processes in the cochlea, supported by his observations that combination tones persisted even with sources producing objectively pure tones.[19] This insight shifted understanding from mere musical curiosities to evidence of the ear's active role in sound processing.[19] Helmholtz's investigations profoundly influenced acoustics by integrating principles from physics, physiology, and music theory, laying foundational concepts for psychoacoustics.[20] His demonstration of auditory nonlinearity through combination tones highlighted the ear's limitations and capabilities in perceiving harmony and dissonance, inspiring subsequent research into hearing mechanisms and sound synthesis.[19] By bridging empirical experimentation with theoretical modeling, Helmholtz established combination tones as a key phenomenon illustrating the interplay between mechanical vibrations and neural sensation.[19]Types of Combination Tones

Difference Tones

Difference tones are a primary type of combination tone generated psychoacoustically when two simultaneous primary tones interact within the auditory system, with the frequency of the difference tone given by the formula , where are the frequencies of the higher and lower primary tones, respectively.[1] These tones arise from nonlinear distortion processes in the inner ear and are also known as Tartini tones, named after the violinist Giuseppe Tartini who first described them as the "terzo suono" or third sound in 1714.[21] Among combination tones, difference tones are the most prominent and easiest to perceive, often becoming audible at lower intensities than summation or higher-order tones, typically requiring primary tone levels around 50-60 dB for clear detection.[1] Their strength increases with the intensity and proximity of the primary tones, particularly for musical intervals smaller than an octave, such as perfect fifths or thirds, where they can enhance perceived consonance.[21] A representative example occurs with primary tones at 300 Hz and 400 Hz, producing a difference tone at 100 Hz, which manifests as a low, buzzing pitch.[10] In a musical context, a perfect fifth interval, such as G4 at approximately 392 Hz and D5 at 587 Hz, yields a difference tone near 195 Hz, closely approximating the pitch of G3 (open G string) at 196 Hz and aiding violinists in tuning.[21] Auditorily, difference tones exhibit a steady pitch that remains consistent during sustained primary tones and can achieve loudness comparable to the primaries at high volumes, though they are generally fainter.[1] If the frequency of one primary tone decreases, the difference tone descends in pitch accordingly, maintaining its perceptual stability as a distinct, low-frequency sensation.[21]Summation and Higher-Order Tones

Summation tones arise from the addition of the frequencies of two primary tones, resulting in a perceived tone at frequency . These tones are generally less audible than difference tones due to their higher frequencies, which place them in regions where auditory sensitivity decreases, and because they are readily masked by the louder primary tones. Psychoacoustic studies indicate that summation tones require primary tone intensities of at least 50–60 dB for detectability, though their perception remains faint and varies significantly among individuals owing to nonlinearities in the inner ear.[1] For instance, when primary tones at 200 Hz and 300 Hz are presented at sufficient loudness, a summation tone at 500 Hz may emerge, but it is subtle and best perceived in quiet acoustic environments to minimize masking effects. Higher summation orders, such as , are even rarer and demand greater intensities, often exceeding 80 dB, for any perceptible presence.[22][23] Higher-order combination tones encompass more complex intermodulation products beyond simple summation or first-order differences, including cubic terms like or , and in multi-tone scenarios, products such as . These tones are weaker in amplitude—typically 20–40 dB below the primaries—and require elevated primary levels, often above 70–90 dB SPL, to become audible, as their generation stems from higher-degree nonlinear distortions in the cochlea. Their audibility further diminishes with increasing order, with perceptions reported up to fifth- or sixth-order in controlled experiments.[25] In the perceptual hierarchy of combination tones, difference tones are most prominent and easiest to detect at moderate intensities, summation tones serve a secondary role with limited salience, and higher-order tones occupy a tertiary position, exhibiting progressively reduced audibility as complexity and required stimulus levels increase. This hierarchy reflects the ear's differential sensitivity to subtractive versus additive and multi-component distortions.[26][25]Mechanisms and Theory

Nonlinear Distortion in the Ear

The basilar membrane in the cochlea exhibits nonlinear compression, where vibrations are amplified for low-intensity sounds but compressed for high-intensity ones, primarily due to the active electromotility of outer hair cells. This nonlinearity generates distortion products, including harmonics and intermodulation tones, as the outer hair cells respond asymmetrically to the traveling waves induced by primary tones. Such distortions arise from the voltage-dependent length changes in outer hair cells, which enhance sensitivity and frequency selectivity while introducing audible combination tones not present in the external sound field.[27][28] Combination tones are generated predominantly within the cochlea, the inner ear structure housing the organ of Corti, where outer hair cells interact with the basilar membrane to produce these products through local mechanical interactions. The middle ear, including its muscles, responds linearly to sound and does not contribute significantly to distortion generation, as evidenced by the absence of distortion in isolated middle ear preparations. While central neural processing in the auditory pathway may influence perception, the primary site of origin is the cochlear periphery, excluding the outer ear or the sound source itself.[11][27] Supporting physiological evidence includes otoacoustic emissions, low-level sounds emitted by the cochlea in response to acoustic stimuli, which replicate the frequency patterns of combination tones and demonstrate the active, nonlinear role of outer hair cells in distortion production. These emissions, measurable in the ear canal, confirm that the cochlea not only receives but also generates sound components akin to perceived combination tones, underscoring the organ's self-sustaining mechanical activity.[27][29] The degree of cochlear nonlinearity is intensity-dependent, with distortion products emerging more prominently as sound pressure levels increase from low to moderate ranges, explaining why combination tones are typically inaudible at soft volumes but detectable at louder ones. This level-dependent behavior reflects the compressive nature of outer hair cell amplification, which saturates at higher intensities while enhancing weaker signals.[27]Mathematical Description

Combination tones arise in nonlinear acoustic systems, such as the human ear, where the output displacement is not linearly proportional to the input pressure . This relationship is mathematically modeled using a Taylor series expansion around the operating point of the system's transfer function, representing the pressure-displacement dynamics in the cochlea: where , , and are coefficients characterizing the linear, quadratic, and cubic nonlinearities, respectively. For two primary tones, the input is , with and amplitudes and . This expansion captures how nonlinearities generate intermodulation products, including combination tones, as distortion components in the output spectrum.[30] The quadratic term produces second-order combination tones at frequencies (difference tone) and (summation tone). Substituting the input yields cross-modulation components with amplitudes proportional to the product ; specifically, the sinusoidal component at has amplitude . The relative level of this difference tone, compared to the primaries, is approximately dB, assuming the primaries are at similar levels. These predictions align with observations in cochlear mechanics, where quadratic nonlinearities contribute to low-level distortion products.[31][30] Higher-order terms, particularly the cubic term , generate third-order combination tones, with the most prominent being the cubic difference tones at and . The amplitude of the tone scales as (or for the symmetric case), modulated by trigonometric coefficients such as from the expansion. These tones exhibit compressive growth rates around 0.33 dB per dB of primary level increase and can reach levels up to -15 dB relative to the primaries in basilar membrane responses. Such mathematical formulations underpin quantitative psychoacoustic models, including those referenced in standards like ANSI S3.4 for auditory perception.[31][30]Applications in Music and Acoustics

Tuning and Intonation

Combination tones, particularly difference tones known as Tartini tones, serve as a practical aid for string players in achieving precise intonation. Violinists and other string instrumentalists listen for the emergence of a clear, low Tartini tone when playing intervals such as perfect fifths, where a just intonation ratio of 3:2 (e.g., A at 440 Hz and E at 660 Hz producing a 220 Hz tone) indicates accurate tuning.[32][33] This auditory cue, often perceived as a soft, bell-like vibration, allows performers to adjust finger positions dynamically for purer intervals during practice or performance.[34] In ensemble playing, Tartini tones facilitate synchronization of pitches in double stops and chords by reinforcing the perceived fundamental frequency, creating a sense of unified resonance when notes align correctly. For instance, in violin double stops, the tone's presence confirms harmonic coherence, helping musicians blend with others in chamber settings or orchestras.[34][33] Historically, Giuseppe Tartini utilized these tones to advocate for "true" harmony based on just intonation, contrasting it with the compromises of tempered scales, as outlined in his 1754 Trattato di musica secondo la vera scienza dell'armonia.[16] In modern contexts, this approach persists in just intonation advocacy through ear-training resources and pedagogical texts, such as those emphasizing adjustments like flattening major thirds by 14 cents for chordal purity.[16][33] However, Tartini tones can mislead performers in equal temperament systems, where intervals like major thirds produce difference tones that deviate from expected fundamentals (e.g., sharp by about 66 cents), potentially disrupting perceived tuning accuracy.[32]Instrument Design

In pipe organ design, resultant bass stops exploit combination tones to simulate deep pedal tones without requiring impractically large pipes. These stops pair ranks tuned to higher harmonics, generating a perceived fundamental through the difference tone between them. For instance, a 32' resultant bass is produced by combining a 16' rank (second harmonic) with a 10 2/3' quint rank (third harmonic), yielding a difference frequency equivalent to the 32' pitch.[35] This approach, dating back to early 19th-century innovations, allows for extended bass ranges in compact organ chambers while maintaining tonal balance.[35] For string instruments like the violin, body resonances play a key role in modulating combination tones, either amplifying desirable ones or suppressing artifacts that could muddy the sound. The air cavity and structural modes interact with played fundamentals to generate nonlinear products, influencing the instrument's overall voicing. Experimental analyses reveal that old Italian violins exhibit stronger combination tones compared to modern counterparts, attributed to optimized air resonance around 250-300 Hz from their graduated plate thicknesses and varnish compositions.[36] In one study, a 1700 violin by Carlo Annibale Tononi produced the most prominent Tartini tones—audible third tones from double-stops—among instruments tested, highlighting how historical crafting enhances these effects for richer timbre.[36] Luthiers thus prioritize resonance tuning during construction to leverage these tones without introducing dissonance. Wind instrument design accounts for internal combination tones arising from nonlinear interactions along the bore, where propagating harmonics produce intermodulation products that shape timbre. In brass instruments, for example, high-amplitude waves cause distributed nonlinearity, generating additional frequencies beyond the primary harmonic series and contributing to the "brassy" quality at forte dynamics.[37] Designers adjust bore geometry, wall thickness, and material properties—such as using thicker brass in trumpets—to control these effects, minimizing unwanted dissonant tones while preserving spectral richness.[37] Similar considerations apply to woodwinds, where reed vibrations and air column nonlinearities can introduce combination tones; tuning focuses on flare and taper to balance warmth and clarity. In modern digital synthesis, virtual instruments employ algorithms to replicate or counteract combination tones for authentic acoustic emulation. Physical modeling techniques, such as digital waveguide networks, incorporate nonlinear filters to simulate distortion products from real instrument mechanics, ensuring spectra match observed behaviors like those in brass or strings.[38] For avoidance, subtractive synthesis uses gentle clipping or dynamic EQ to suppress intermodulation in polyphonic patches, while additive methods explicitly add modeled tones for controlled realism in software organs or orchestral libraries.[38]References

- https://www.[science](/page/Science).org/doi/10.1126/science.451625