Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

WASP-17b

View on Wikipedia

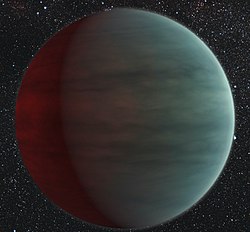

Artist impression of Ditsö̀ | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | David R. Anderson et al |

| Discovery date | 11 August 2009 |

| Transit (including secondary eclipse) | |

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |

| 0.05151±0.00035 AU | |

| Eccentricity | <0.020 |

| 3.7354845±0.0000019 d | |

| Inclination | 86.83°+0.68° −0.53° |

| −70 or 210 [citation needed] | |

| Semi-amplitude | 56.0+4.1 −4.0 m/s |

| Star | WASP-17 |

| Physical characteristics[2] | |

| 1.991±0.081 RJ | |

| Mass | 0.512±0.037 MJ |

Mean density | 0.080+0.013 −0.011 g/cm3 |

| Temperature | 1,550+170 −200 K[3] |

WASP-17b, officially named Ditsö̀[pronunciation?], is an exoplanet in the constellation Scorpius that is orbiting the star WASP-17. Its discovery was announced on 11 August 2009.[1] It is the first planet discovered to have a retrograde orbit, meaning it orbits in a direction counter to the rotation of its host star.[1] This discovery challenged traditional planetary formation theory.[4] In terms of diameter, WASP-17b is one of the largest exoplanets discovered and at half Jupiter's mass, this made it the most puffy planet known in 2010.[5] On 3 December 2013, scientists working with the Hubble Space Telescope reported detecting water in the exoplanet's atmosphere.[6][7]

WASP-17b's name was selected in the NameExoWorlds campaign by Costa Rica, during the 100th anniversary of the International Astronomical Union. Ditsö̀ is the name that the god Sibö̀ gave to the first Bribri people in Talamancan mythology.[8][9]

Discovery

[edit]A team of researchers led by David Anderson of Keele University in Staffordshire, England, discovered the gas giant, which is about 1,000 light-years (310 parsecs) from Earth, by observing it transiting its host star WASP-17. Such photometric observations also reveal the planet's size. The discovery was made with a telescope array at the South African Astronomical Observatory. Due to the involvement of the Wide Angle Search for Planets (SuperWASP) consortium of universities, the exoplanet, as the 17th found to date by this group, was given its present name.[10]

Astronomers at the Observatory of Geneva were then able to use characteristic redshifts and blueshifts in the host star's spectrum as its radial velocity varied over the course of the planet's orbit to measure the planet's mass and obtain an indication of its orbital eccentricity.[1] Careful examination of the Doppler shifts during transits also allowed them to determine the direction of the planet's orbital motion relative to its parent star's rotation via the Rossiter–McLaughlin effect.[1]

Orbit

[edit]WASP-17b is thought to have a retrograde orbit (with a sky-projected inclination of the orbit normal against the stellar spin axis of about 149°,[11] not to be confused with the line-of-sight inclination of the orbit, given in the table, which is near 90° for all transiting planets), which would make it the first planet discovered to have such an orbital motion. It was found by measuring the Rossiter–McLaughlin effect of the planet on the star's Doppler signal as it transited, in which whichever of the star's hemispheres is turning toward or away from Earth will show a slight blueshift or redshift which is dampened by the transiting planet. Scientists are not yet sure why the planet orbits opposite to the star's rotation. Theories include a gravitational slingshot resulting from a near-collision with another planet, or the intervention of a smaller planet-like body working to gradually change WASP-17b's orbit by tilting it via the Kozai mechanism.[12]

Spin-orbit angle measurement was updated in 2012 to −148.7+7.7

−6.7°.[13]

Physical properties

[edit]

WASP-17b has a radius between 1.5 and 2 times that of Jupiter and about half the mass.[1] Thus its mean density is between 0.08 and 0.19 g/cm3,[1] compared with Jupiter's 1.326 g/cm3[14] and Earth's 5.515 g/cm3 (the density of water is 1 g/cm3). The unusually low density is thought to be a consequence of a combination of the planet's orbital eccentricity and its proximity to its parent star (less than one seventh of the distance between Mercury and the Sun), leading to tidal flexing and heating of its interior.[1] The same mechanism is behind the intense volcanic activity of Jupiter's moon Io. WASP-39b has a similarly low estimated density.

Exoplanetary sodium in the atmosphere of the WASP-17 has been detected in 2018,[3] but was not confirmed by 2021. Instead, the spectral signatures of water, aluminium oxide (AlO) and titanium hydride (TiH) were detected.[15] The water signature was confirmed in 2022, together with carbon dioxide absorption.[16] In 2023, evidence of clouds made of quartz was detected on the planet by the James Webb Space Telescope.[17][18]

From top left to lower right: WASP-12b, WASP-6b, WASP-31b, WASP-39b, HD 189733 b, HAT-P-12b, WASP-17b, WASP-19b, HAT-P-1b and HD 209458 b

See also

[edit]- HAT-P-7b, another exoplanet announced to have a retrograde orbit the day after the WASP-17b announcement

- TrES-4b, another large exoplanet with a low density

- List of exoplanet extremes

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Anderson, D. R.; et al. (2010). "WASP-17b: An Ultra-Low Density Planet in a Probable Retrograde Orbit". The Astrophysical Journal. 709 (1): 159–167. arXiv:0908.1553. Bibcode:2010ApJ...709..159A. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/709/1/159. S2CID 53628741.

- ^ a b Bonomo, A. S.; Desidera, S.; et al. (June 2017). "The GAPS Programme with HARPS-N at TNG. XIV. Investigating giant planet migration history via improved eccentricity and mass determination for 231 transiting planets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 602: A107. arXiv:1704.00373. Bibcode:2017A&A...602A.107B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629882. S2CID 118923163.

- ^ a b Khalafinejad, Sara; Salz, Michael; et al. (October 2018). "The atmosphere of WASP-17b: Optical high-resolution transmission spectroscopy". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 618: A98. arXiv:1807.10621. Bibcode:2018A&A...618A..98K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201732029. S2CID 119007114.

- ^ "A planet going the wrong way", Phys Org. June 7, 2011. Accessed June 10, 2011

- ^ Kaufman, Rachel (17 August 2009). ""Backward" Planet Has Density of Foam Coffee Cups". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on August 20, 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Hubble Traces Subtle Signals of Water on Hazy Worlds". NASA. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Mandell, Avi M.; Haynes, Korey; Sinukoff, Evan; Madhusudhan, Nikku; Burrows, Adam; Deming, Drake (3 December 2013). "Exoplanet Transit Spectroscopy Using WFC3: WASP-12 b, WASP-17 b, and WASP-19 b". Astrophysical Journal. 779 (2): 128. arXiv:1310.2949. Bibcode:2013ApJ...779..128M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/779/2/128. S2CID 52997396.

- ^ "Approved names". NameExoworlds. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ "100 000s of People from 112 Countries Select Names for Exoplanet Systems In Celebration of IAU's 100th Anniversary". International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 2022-12-05. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (August 13, 2009). "New planet displays exotic orbit". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ Amaury H.M.J. Triaud et al. Spin-orbit angle measurements for six southern transiting planets. Accepted for publication in A&A 2010. arXiv preprint

- ^ Grossman, Lisa (August 13, 2009). "Planet found orbiting its star backwards". New Scientist. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ Albrecht, Simon; Winn, Joshua N.; Johnson, John A.; Howard, Andrew W.; Marcy, Geoffrey W.; Butler, R. Paul; Arriagada, Pamela; Crane, Jeffrey D.; Shectman, Stephen A.; Thompson, Ian B.; Hirano, Teruyuki; Bakos, Gaspar; Hartman, Joel D. (2012), "Obliquities of Hot Jupiter Host Stars: Evidence for Tidal Interactions and Primordial Misalignments", The Astrophysical Journal, 757 (1): 18, arXiv:1206.6105, Bibcode:2012ApJ...757...18A, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/757/1/18, S2CID 17174530

- ^ "Jupiter Fact Sheet". Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ Saba, Arianna; Tsiaras, Angelos; Morvan, Mario; Thompson, Alexandra; Changeat, Quentin; Edwards, Billy; Jolly, Andrew; Waldmann, Ingo; Tinetti, Giovanna (2022), "The Transmission Spectrum of WASP-17 b from the Optical to the Near-infrared Wavelengths: Combining STIS, WFC3, and IRAC Data Sets", The Astronomical Journal, 164 (1): 2, arXiv:2108.13721, Bibcode:2022AJ....164....2S, doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac6c01, S2CID 237363318

- ^ Alderson, L.; Wakeford, H. R.; MacDonald, R. J.; Lewis, N. K.; May, E. M.; Grant, D.; Sing, D. K.; Stevenson, K. B.; Fowler, J.; Goyal, J.; Batalha, N. E.; Kataria, T. (2022), "A comprehensive analysis of WASP-17b's transmission spectrum from space-based observations", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 512 (3): 4185–4209, arXiv:2203.02434, doi:10.1093/mnras/stac661

- ^ Grant, David; Lewis, Nikole K.; et al. (October 2023). "WST-TST DREAMS: Quartz Clouds in the Atmosphere of WASP-17b". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 956 (2): L29. arXiv:2310.08637. Bibcode:2023ApJ...956L..32G. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/acfc3b.

- ^ "NASA's Webb Detects Tiny Quartz Crystals in Clouds of Hot Gas Giant". webbtelescope.org. STScI. 16 October 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "Composition of cloud particles - hot gas giant exoplanet WASP-17b". October 20, 2023.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to WASP-17b at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to WASP-17b at Wikimedia Commons

- Alexander, Amir. Scientists Detect "Wrong-Way" Planet. [1] Archived 2009-08-16 at the Wayback Machine The Planetary Society, August 12, 2009. Accessed August 14, 2009.

WASP-17b

View on GrokipediaDiscovery and Nomenclature

Discovery

WASP-17b was discovered through the transit method as part of the Wide Angle Search for Planets (WASP) consortium survey and announced on August 11, 2009, via submission to arXiv by the discovery team.[9] The planet was initially detected using photometric observations from the SuperWASP-South telescope array, which recorded 15,509 measurements of the host star between 2006 and 2008, identifying periodic dips in brightness indicative of a transiting exoplanet.[1] The discovery was led by David R. Anderson and a collaborative team from institutions including Keele University in the United Kingdom and the Geneva Observatory in Switzerland.[1] Confirmation followed through radial velocity measurements obtained with the CORALIE spectrograph on the Euler 1.2 m telescope at La Silla Observatory in Chile, supplemented by high-precision spectra from the HARPS instrument on the ESO 3.6 m telescope, which revealed the planet's orbital motion around the host star.[1] These observations ruled out false positives and provided initial constraints on the system's parameters. The initial findings, including the first light curve analysis using Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods to model the transit and determine an orbital period of approximately 3.74 days, were detailed in a paper published in the Astrophysical Journal in 2010.[1] Ground-based follow-up photometry was conducted at the South African Astronomical Observatory using the EulerCam on the Euler-Swiss telescope to confirm the transit depth and timing, ensuring the signal's consistency with a planetary transit.[1] This discovery marked WASP-17b as the first exoplanet suggested to possess a retrograde orbit, opposite to the direction of its host star's rotation.[1]Nomenclature

WASP-17b received its provisional designation upon discovery, following the standard convention for exoplanets detected by the Wide Angle Search for Planets (WASP) survey, where the host star is numbered sequentially (WASP-17) and planets are lettered alphabetically starting with 'b' for the innermost or first confirmed. In December 2019, as part of the International Astronomical Union (IAU)'s centennial NameExoWorlds contest, the system was assigned to Costa Rica for public naming, resulting in the official approval of Ditsö̀ for the planet and Dìwö for the host star. These names derive from the Bribri language of the indigenous Talamanca people in Costa Rica; Dìwö means "the Sun," while Ditsö̀ refers to the name bestowed by the creator god Sibö̀ upon the first Bribri people in Talamancan mythology, symbolizing reflection and origin. The IAU's exoplanet naming guidelines, established to promote global participation and cultural diversity, require that official names for exoplanets and their host stars form a thematic pair, draw from mythology, literature, or cultural heritage (preferring indigenous or lesser-known traditions), and avoid references to individuals, places, brands, or politically sensitive terms. This contest, held during the IAU's 100th anniversary, encouraged submissions from national organizing committees to foster international collaboration in astronomy and highlight underrepresented cultural narratives in celestial nomenclature.Host Star

Characteristics

WASP-17 is classified as an F6V main-sequence star with an effective temperature of 6550 ± 100 K.[1] Its mass is determined to be 1.20^{+0.10}{-0.11} M\sun, and its radius measures 1.38^{+0.20}{-0.18} R\sun.[1] The star exhibits sub-solar metallicity, with an iron abundance of [Fe/H] = -0.25 ± 0.09.[1] Isochrone fitting yields an estimated age for WASP-17 of 3.0^{+0.9}_{-2.6} Gyr.[1] The star displays low chromospheric activity. WASP-17 shows moderate rotational broadening, with a projected equatorial velocity of v \sin i = 9.0 ± 1.5 km s^{-1}, which corresponds to an expected rotation period of approximately 8.5–11 days given the stellar radius.[1]Location and Visibility

The WASP-17 system is located in the constellation Scorpius, at equatorial coordinates of right ascension 15ʰ 59ᵐ 51ˢ and declination −28° 03′ 42″ (J2000 epoch).[2] It lies approximately 1,310 light-years (403 parsecs) from Earth, a distance refined through parallax measurements from the Gaia mission's Data Release 3 (2022).[2][10] This places the system in a region of the southern celestial sky, accessible primarily to observers in the Southern Hemisphere. The host star WASP-17 has an apparent visual magnitude of V = 11.6, rendering it faint enough to require mid-sized telescopes (typically 8–12 inches in aperture) for detailed observation under dark skies.[1] Due to its southern declination, the system is best observed from latitudes south of 30° N, where it reaches higher altitudes and avoids horizon obstruction. Seasonal visibility peaks in the evening sky from April to July for Southern Hemisphere observers, when Scorpius transits near midnight.[11] In Galactic coordinates, WASP-17 resides at longitude 346° and latitude +19°, positioning it in the general direction of the Galactic plane and subject to moderate interstellar reddening along the line of sight.[2] Observations account for an estimated E(B–V) reddening of about 0.05 magnitudes, which minimally affects photometric studies but is corrected for in spectral analyses.[12]Orbital Characteristics

Parameters

The orbital parameters of WASP-17b were determined primarily through analysis of photometric transit light curves and radial velocity measurements, providing key geometric elements of its orbit around the host star WASP-17. These parameters describe the size, shape, and orientation of the orbit, essential for modeling the planet's transit events and dynamical evolution. The values reflect refinements from multiple observations, confirming a close-in, short-period orbit typical of hot Jupiters.| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Orbital period (P) | 3.735485 ± 0.000002 days | [13] |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 0.05151 ± 0.00035 AU | [14] |

| Eccentricity (e) | < 0.020 (nearly circular) | [14] |

| Inclination (i) | 87.22° ± 0.14° | [13] |

Dynamics

WASP-17b orbits its host star in a retrograde direction, with a sky-projected spin-orbit misalignment angle of approximately 149°, as measured through observations of the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect.[17] This effect, caused by the planet blocking portions of the rotating stellar disk during transit, distorts the radial velocity signal and reveals the misalignment between the planet's orbital plane and the star's equatorial plane. The measurement was obtained in 2010 using the HARPS spectrograph on the 3.6 m ESO telescope, confirming the retrograde nature independently from preliminary indications. The orbit exhibits long-term stability, attributed to its low eccentricity (consistent with circular) and the absence of known additional planets in the system, which minimizes perturbations.[18] As a hot Jupiter with an orbital period of 3.7 days, WASP-17b resides close to its star without significant dynamical instabilities expected over planetary timescales. The retrograde alignment suggests a complex migration history, where WASP-17b likely formed at a greater distance from its star—beyond the snow line—and migrated inward through interactions such as planet-planet scattering, which can induce large obliquities and reverse the orbital direction. This mechanism contrasts with standard disk-driven migration, which typically preserves alignment, and aligns with dynamical models for misaligned hot Jupiters.[17] Tidal interactions between WASP-17b and its host star are expected to enforce strong tidal locking, synchronizing the planet's rotation with its orbital motion due to the short orbital period and proximity. Additionally, these tides are expected to drive a gradual orbital decay.Physical Characteristics

Size and Mass

WASP-17b possesses a radius of 1.93 ± 0.05 Jupiter radii, establishing it as one of the largest known exoplanets. This dimension was derived from the transit depth, quantified as , through analysis of photometric observations including Spitzer data combined with prior transit light curves via Markov chain Monte Carlo fitting.[19] The planet's mass measures 0.48 ± 0.03 Jupiter masses, obtained by fitting radial velocity curves to yield the minimum mass , where is the orbital period and is the radial velocity semi-amplitude of approximately 0.053 km/s measured with the CORALIE and HARPS spectrographs. Since WASP-17b transits its host star, the inclination is near 90°, allowing the true mass to be approximated closely from this value.[1] Uncertainties in both radius and mass arise primarily from assumptions in limb darkening models applied to transit photometry and from stellar parameters, including the host star's radius (1.572 ± 0.056 solar radii) and mass (1.306 ± 0.026 solar masses), which propagate through the fitting process. Compared to Jupiter, WASP-17b exhibits a substantially larger radius but lower mass, signifying an exceptionally low overall density.Density and Temperature

WASP-17b exhibits an exceptionally low bulk density of 0.09 ± 0.02 g/cm³, approximately 7% of Jupiter's density of 1.33 g/cm³, signifying a highly inflated gaseous envelope that distinguishes it among known exoplanets. This value derives from radial velocity and transit measurements yielding a planetary mass of about 0.48 M_Jup and radius of roughly 1.93 R_Jup, resulting in a structure far less compact than typical gas giants. The low density implies a puffed-up atmosphere, with the planet's surface gravity consequently reduced to log g ≈ 2.7 (in cm/s² units), facilitating an extended scale height that enhances transit signals and atmospheric observability.[2] The planet's equilibrium temperature is approximately 1,770 K, computed via the formula , under assumptions of zero Bond albedo (A = 0) and full heat redistribution. Secondary eclipse observations reveal a hotter dayside temperature of around 1,800 K, reflecting intense stellar irradiation on the tidally locked facing hemisphere and a modest day-night contrast, with recent JWST measurements indicating a cooler nightside around 1,000 K. These thermal properties position WASP-17b at the boundary between hot and ultra-hot Jupiters, influencing its atmospheric dynamics.[20][21][22] The inflation of WASP-17b's envelope arises primarily from radiative heating by its host star, which deposits energy into the upper atmosphere and, coupled with reduced opacity from molecular dissociation at high temperatures, prevents contraction and sustains the expanded structure. Models indicate that about 70% of the absorbed stellar energy is redistributed across the planet, mitigating extreme temperature gradients while contributing to the overall bloating observed in low-gravity hot Jupiters like this one. This mechanism aligns with theoretical expectations for irradiated worlds, where internal cooling is inhibited by the insulating effect of the heated envelope.[23][21]Atmosphere

Observations

The primary observational techniques for probing WASP-17b's atmosphere include transmission spectroscopy, which measures variations in transit depth across wavelengths to infer atmospheric absorption features, and emission spectroscopy, which analyzes contrasts during secondary eclipses to characterize thermal emission from the planet's dayside or nightside.[24][25] Early atmospheric observations of WASP-17b were conducted using the Hubble Space Telescope's Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) in 2013, employing transmission spectroscopy to detect faint signatures of water vapor in the near-infrared spectrum from 1.1 to 1.7 μm. This marked one of the first detections of molecular features in the planet's extended atmosphere, highlighting its hazy composition despite challenges from scattering.[26] Ground-based efforts in the 2010s supplemented space-based data with near-infrared transit observations to refine the transmission spectrum. A tentative detection of sodium absorption was reported in 2018 using high-resolution optical spectroscopy, suggesting potential alkali metal presence, though subsequent analyses failed to confirm this feature.[27] The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) era began with Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) low-resolution spectrometer observations in March 2023, yielding a transmission spectrum spanning 5–12 μm that resolved distinct opacity features, including a prominent silicate signature at 8.6 μm.[5] These data provided unprecedented mid-infrared coverage, revealing the influence of high-altitude clouds on the planet's atmospheric transmission.[24] Subsequent JWST eclipse spectroscopy using the Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) single-object slitless spectroscopy (SOSS) mode in 2024 targeted the dayside emission spectrum from 0.8 to 5.3 μm, confirming a brightness temperature of approximately 1,400 K consistent with the planet's equilibrium temperature.[21] This observation, analyzed in early 2025, demonstrated strong water absorption and supersolar metallicity on the dayside.[28] In 2025, NIRSpec prism G395H observations further advanced nightside characterization through combined transit and eclipse measurements across 2.7–5.3 μm, employing phase-interpolated emission (PIE) techniques to isolate thermal contrasts and reveal chemical disequilibrium processes.[25] These results, detailed in Gressier et al., highlighted heterogeneous emission and informed models of atmospheric circulation.[29]Composition

The atmosphere of WASP-17b features a composition dominated by molecular hydrogen and helium, with significant enrichment in key trace gases and aerosols. Water vapor (H₂O) has been detected at super-solar abundances, with retrieval analyses from near-infrared transmission spectroscopy yielding log(H₂O) ≈ -2.96, indicating an oxygen-rich environment consistent with enhanced volatile delivery during formation.[7] The planet's metallicity is super-solar, exceeding 30 times solar levels based on dayside emission spectroscopy, which reflects high enrichment in heavy elements relative to hydrogen.[21] This is evidenced by oxygen-to-hydrogen (O/H) ratios with a 3σ lower limit greater than 3 times solar and a maximum likelihood estimate around 100 times solar, while carbon-to-hydrogen (C/H) ratios remain comparatively lower, contributing to an overall metal enhancement of approximately 10 times solar or more. The carbon-to-oxygen (C/O) ratio is sub-solar at ≈0.3 or below, signifying an oxygen-dominated chemistry that favors water and silicates over carbon-bearing species like methane.[21] High-altitude hazes in the atmosphere consist of nanocrystalline quartz (SiO₂) particles, approximately 0.01 μm in size, forming a reflective cloud deck that scatters and absorbs mid-infrared light at 8.6 μm.[24] These clouds arise from silicon oxide condensation in the hot, oxygen-rich upper layers and are shaped by strong equatorial winds exceeding 4 km/s (about 10,000 mph), which align the crystals and drive horizontal transport across the tidally locked planet. Atmospheric models for WASP-17b invoke equilibrium chemistry at its high temperatures (around 1,800 K), where photochemistry and thermal dissociation suppress methane formation in favor of CO and CO₂, though vertical mixing introduces disequilibrium effects by transporting deeper, metal-enriched gases upward.[21] This low mean molecular weight, primarily from the H₂-He dominance despite elevated metallicity, supports the planet's extreme radius inflation by enhancing atmospheric opacity and heat retention.[21]References

- https://science.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/missions/webb/webb-detects-tiny-quartz-crystals-in-the-clouds-of-a-hot-gas-giant/