Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wacker process

View on WikipediaThe Wacker process or the Hoechst-Wacker process (named after the chemical companies of the same name) is an industrial chemical reaction: the aerobic oxidation of ethylene to acetaldehyde in the presence of catalytic, aqueous palladium(II) chloride and copper(II) chloride.

The Tsuji-Wacker oxidation refers to a family of reactions inspired by the Wacker process. In Tsuji-Wacker reactions, palladium(II) catalyzes transformation of α-olefins into carbonyl compounds in various solvents.

The development of the Wacker process popularized modern organopalladium chemistry, and Tsuji-Wacker oxidations remain in use today.

History

[edit]The Wacker process was one of the first homogeneous catalysis with organopalladium chemistry applied on an industrial scale.[1]

In an 1893 doctoral dissertation on Pennsylvanian natural gas, Francis Clifford Phillips had reported that palladium(II) chloride oxidized ethylene to acetaldehyde, but the reaction required stoichiometric quantities of palladium.[2] It remained a niche curiosity until Wacker Chemie began developing its eponymous process in 1956.[3]

At the time, many industrial compounds were produced via acetaldehyde from acetylene, itself from calcium carbide. The overall route exhibited poor thermodynamic efficiency and required great expense. Esso sought to market waste olefins from a new, under-construction oil refinery in Cologne close to a Wacker site. Wacker realized that ethylene would be a cheaper feedstock than acetylene, and began to investigate catalytic oxidation to ethylene oxide.[3]

To Wacker's surprise, they smelled[Note 1] not ethylene oxide but acetaldehyde in the product stream. From Phillips' dissertation, known properties of Zeise's salt, and transformation of the catalyst over the course of a batch reaction, Wacker realized that they needed to reoxidize the palladium to close the catalytic cycle.[3] They began publishing the process outline in 1957.[4][5] However, poor patenting strategy allowed parent corporation Hoechst AG to outrace Wacker to the optimal catalysis conditions.[3][6][7]

Wacker-Hoechst began jointly constructing pilot plants in 1958, but the relatively aggressive reaction conditions required the first large-scale use of titanium metal in the European chemical industry to protect against corrosion. Production plants started operation in 1960.[3]

The process also sparked a boom in organopalladium chemistry.[3] Studies from the 1960s elucidated several key points about the reaction mechanism through kinetic isotope effects (or lack thereof) and stereochemistry.[8][9] Many focused on the hydroxypalladation step, which forms the C–O bond. Early reactions used conditions much milder than the industrial plants and obtained contradictory results; the modern consensus is that the step's stereochemistry is quite sensitive to chloride concentrations.[9]

Other studies investigated reaction's application to more complex terminal olefins. High-order olefins are insoluble in water, but Clement and Selwitz[10] found that aqueous DMF as solvent allowed for the oxidation of 1-dodecene to 2-dodecanone. Fahey[11] noted the use of 3-methylsulfolane in place of DMF as solvent increased the yield of oxidation of 3,3-Dimethylbut-1-ene. Two years after, Tsuji[12] applied the Clement-Selwitz conditions for selective oxidations of terminal olefins with multiple functional groups, and demonstrated its utility in synthesis of complex substrates.[13]

Carbonylation has mainly superseded the Wacker process for modern bulk chemical synthesis, but small-scale Tsuji-Wacker reactions remain important for fine chemical and laboratory-scale syntheses.[3]

Reaction mechanism

[edit]The reaction mechanism for the industrial Wacker process (olefin oxidation via palladium(II) chloride) has received significant attention for several decades. Aspects of the mechanism are still debated. A modern formulation is described below:[14]

This reaction can also be described as follows:

- [PdCl4]2 − + C2H4 + H2O → CH3CHO + Pd + 2 HCl + 2 Cl−,

followed by reactions that regenerate the Pd(II) catalyst:

- Pd + 2 CuCl2 + 2 Cl − → [PdCl4]2− + 2 CuCl

- 2 CuCl + 1/2 O2 + 2 HCl → 2 CuCl2 + H2O

Only the alkene and oxygen are consumed. Without copper(II) chloride as an oxidizing agent, Pd(0) metal (resulting from beta-hydride elimination of Pd(II) in the final step) would precipitate, stopping Philips' reaction after one cycle. Air, pure oxygen, or a number of other reagents can then oxidise the resultant CuCl-chloride mixture back to CuCl2, allowing the cycle to continue.

High concentrations of chloride and copper(II) chloride favor formation of a new product, ethylene chlorohydrin.[15]

Evidence

[edit]Evidence for the overall mechanism includes:[8][9]

- No H/D exchange effects. Experiments with C2D4 in water generate CD3CDO, and runs with C2H4 in D2O generate CH3CHO. Thus, keto-enol tautomerization is not a possible mechanistic step.

- Negligible kinetic isotope effect with fully deuterated reactants (k H/k D=1.07). Hence hydride transfer is not rate-determining.

- Significant competitive isotope effect with C2H2D2, (k H/k D= ~1.9), suggests that the rate determining step precedes acetaldehyde formation.

Evidence against the mechanism is a copper-chloride containing byproduct crystallized by Hosokawa et al.[16] Questions remain about whether the cocatalyst also helps hydroxylate the ethylene ligand.

The ethylene ligand's hydroxylation is typically a slow process.[17][18] Depending on experimental conditions, it can occur either intramolecularly, from a palladium-bound hydroxido ligand, or intermolecularly. In the former case the hydroxylation is anti; in the latter, syn. Assuming small amounts of copper, experiments have shown that syn addition occurs at low chloride concentrations (< 1 mol/L, industrial process conditions)[19] and anti addition occurs at high (> 3mol/L) concentrations.[20][21][22][23][excessive citations] The pathway change is probably due to chloride ions saturating the catalyst.[24][25] However, under strictly copper-free conditions, anti addition always occurs, and the rate no longer depends on the ethylene hydrogen isotopes.[26][27]

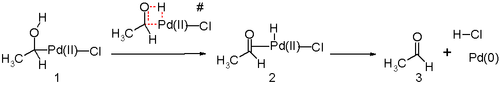

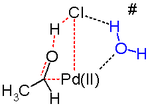

Another key step in the Wacker process is the migration of the hydrogen from oxygen to chloride, followed by reductive elimination to form the C-O double bond. This step is generally thought to proceed through a so-called β-hydride elimination:

The cyclic four-membered transition state shown above is unlikely. In silico studies[28][29][30] argue that the transition state for this reaction step likely involves a 7-membered ring with a (solvent) water molecule acting as a catalyst.

Industrial process

[edit]

Two routes are commercialized for the production of acetaldehyde: one-stage process and two-stage. The acetaldehyde yield is about 95% in either, and byproducts are chlorinated hydrocarbons, chlorinated acetaldehydes, and acetic acid. In general, 100 parts of ethene gives:[31]

- 95 parts acetaldehyde

- 1.9 parts chlorinated aldehydes

- 1.1 parts unconverted ethene

- 0.8 parts carbon dioxide

- 0.7 parts acetic acid

- 0.1 parts chloromethane

- 0.1 parts ethyl chloride

- 0.3 parts ethane, methane, crotonaldehyde

and other minor side products.

The production costs are virtually the same across the two processes; the advantage of using dilute gases in the two-stage method is balanced by higher investment costs. Due to the corrosive nature of the catalyst, either process requires a reactor lined with acid-proof ceramic and titanium tubing, but the two-stage process requires more reactors and piping. Generally, the choice of method is governed by the raw material and energy situations as well as by the availability of oxygen at a reasonable price.[31]

One-stage process

[edit]Ethene and oxygen are passed co-currently in a reaction tower at about 130 °C and 400 kPa.[31] The catalyst is an aqueous solution of PdCl2 and CuCl2. The acetaldehyde is purified by extractive distillation followed by fractional distillation. Extractive distillation with water removes the lights ends having lower boiling points than acetaldehyde (chloromethane, chloroethane, and carbon dioxide) at the top, while water and higher-boiling byproducts, such as acetic acid, crotonaldehyde or chlorinated acetaldehydes, are withdrawn together with acetaldehyde at the bottom.[31]

Two-stage process

[edit]In two-stage process, reaction and oxidation are carried out separately in tubular reactors. Unlike one-stage process, air can be used instead of oxygen. Ethylene is passed through the reactor along with catalyst at 105–110 °C and 900–1000 kPa.[31] Catalyst solution containing acetaldehyde is separated by flash distillation. The catalyst is oxidized in the oxidation reactor at 1000 kPa using air as oxidizing medium. Oxidized catalyst solution is separated and sent back to reactor. Oxygen from air is used up completely and the exhaust air is circulated as inert gas. Acetaldehyde – water vapor mixture is preconcentrated to 60–90% acetaldehyde by utilizing the heat of reaction and the discharged water is returned to the flash tower to maintain catalyst concentration. A two-stage distillation of the crude acetaldehyde follows. In the first stage, low-boiling substances, such as chloromethane, chloroethane and carbon dioxide, are separated. In the second stage, water and higher-boiling by-products, such as chlorinated acetaldehydes and acetic acid, are removed and acetaldehyde is obtained in pure form overhead.[31]

Tsuji-Wacker oxidation

[edit]Development of the reaction system has led to various catalytic systems to address selectivity of the reaction, as well as introduction of intermolecular and intramolecular oxidations with non-water nucleophiles.

Regioselectivity

[edit]Markovnikov addition

[edit]The oxidation of terminal olefins generally provide the Markovnikov ketone product. In rare cases where substrate favors the aldehyde (discussed below), different ligands can be used to enforce Markovnikov regioselectivity. Sparteine (Figure 2, A)[32] favors nucleopalladation at the terminal carbon to minimize steric interaction between the palladium complex and substrate. Quinox (Figure 2, B) favors ketone formation when the substrate contains a directing group.[33] When such substrate bind to Pd(Quinox)(OOtBu), this complex is coordinately saturated which prevents the binding of the directing group, and results in formation of the Markovnikov product. The efficiency of this ligand is also attributed to its electronic property, where anionic TBHP prefers to bind trans to the oxazoline and olefin coordinate trans to the quinoline.[34]

Anti-Markovnikov addition

[edit]The anti-Markovnikov addition selectivity to aldehyde can be achieved through exploiting inherent stereoelectronics of the substrate.[35] Placement of directing group at homo-allylic (i.e. Figure 3, A)[36] and allylic position (i.e. Figure 3, B)[37] to the terminal olefin favors the anti-Markovnikov aldehyde product, which suggests that in the catalytic cycle the directing group chelates to the palladium complex such that water attacks at the anti-Markovnikov carbon to generate the more thermodynamically stable palladacycle. Anti-Markovnikov selectivity is also observed in styrenyl substrates (i.e. Figure 3, C),[38] presumably via η4-palladium-styrene complex after water attacks anti-Markovnikov. More examples of substrate-controlled, anti-Markovnikov Tsuji-Wacker Oxidation of olefins are given in reviews by Namboothiri,[39] Feringa,[35] and Muzart.[40]

Grubbs and co-workers paved way for anti-Markovnikov oxidation of stereoelectronically unbiased terminal olefins, through the use of palladium-nitrite system (Figure 2, D).[41] In his system, the terminal olefin was oxidized to the aldehyde with high selectivity through a catalyst-control pathway. The mechanism is under investigation, however evidence[39] suggests it goes through a nitrite radical adds into the terminal carbon to generate the more thermodynamically stable, secondary radical. Grubbs expanded this methodology to more complex, unbiased olefins.[42][43]

Scope

[edit]Oxygen nucleophiles

[edit]The intermolecular oxidations of olefins with alcohols as nucleophile typically generate ketals, where as the palladium-catalyzed oxidations of olefins with carboxylic acids as nucleophile generates vinylic or allylic carboxylates. In case of diols, their reactions with alkenes typically generate ketals, whereas reactions of olefins bearing electron-withdrawing groups tend to form acetals.[44]

Palladium-catalyzed intermolecular oxidations of dienes with carboxylic acids and alcohols as donors give 1,4-addition products. In the case of cyclohexadiene (Figure 4, A), Backvall found that stereochemical outcome of product was found to depend on concentration of LiCl.[45] This reaction proceeds by first generating the Pd(OAc)(benzoquinone)(allyl) complex, through anti-nucleopalladation of diene with acetate as nucleophile. The absence of LiCl induces an inner sphere reductive elimination to afford the trans-acetate stereochemistry to give the trans-1,4-adduct. The presence of LiCl displaces acetate with chloride due to its higher binding affinity, which forces an outer sphere acetate attack anti to the palladium, and affords the cis-acetate stereochemistry to give the cis-1,4-adduct. Intramolecular oxidative cyclization: 2-(2-cyclohexenyl)phenol cyclizes to corresponding dihydro-benzofuran (Figure 4, B);[46] 1-cyclohexadiene-acetic acid in presence of acetic acid cyclizes to corresponding lactone-acetate 1,4 adduct (Figure 4, C),[47] with cis and trans selectivity controlled by LiCl presence.

Nitrogen nucleophiles

[edit]The oxidative aminations of olefins are generally conducted with amides or imides; amines are thought to be protonated by the acidic medium or to bind the metal center too tightly to allow for the catalytic chemistry to occur.[44] These nitrogen nucleophiles are found to be competent in both intermolecular and intramolecular reactions, some examples are depicted (Figure 5, A,[48] B[49])

Notes

[edit]- ^ Wacker lacked a gas chromatograph at the time.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Elschenbroich, C. "Organometallics" (2006) Wiley-VCH: Weinheim. ISBN 978-3-527-29390-2

- ^ Phillips, Francis C. (March–June 1894). "Researches upon the phenomena of oxidation and chemical properties of gases". American Chemical Journal. 16 (3–6): 163–187, 255–277, 340–365, 406–429 – via Google Books.

The reaction between ethylene and palladium chloride in solution is of the second class and complete, the gas being rapidly absorbed. Palladium is deposited as a black powder, but no trace of oxidation to carbon dioxide occurs. The reaction is almost the same in the cold and at 100°. The gas escaping from the palladium-chloride solution (after complete reduction to metallic palladium) produces no precipitate in lime-water. The reaction between palladium chloride and ethylene leads to the production of aldehyde.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Acetaldehyde from Ethylene — A Retrospective on the Discovery of the Wacker Process Reinhard Jira Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9034–9037 doi:10.1002/anie.200903992

- ^ J. Smidt, W. Hafner, R. Jira, J. Sedlmeier, R. Sieber, R. Rüttinger, and H. Kojer, Angew. Chem., 1959, 71, 176–182. doi:10.1002/ange.19590710503

- ^ J. Smidt, W. Hafner, J. Sedlmeier, R. Jira, R. Rottinger (Cons. f.elektrochem.Ind.), DE 1 049 845, 1959, Anm. 04.01.1957.

- ^ W. Hafner, R. Jira, J. Sedlmeier, and J. Smidt, Chem. Ber., 1962, 95, 1575–1581. doi:10.1002/cber.19620950702

- ^ J. Smidt, W. Hafner, R. Jira, R. Sieber, J. Sedlmeier, and A. Sabel, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1962, 1, 80–88.

- ^ a b Henry, Patrick M. In Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis; Negishi, E., Ed.; Wiley & Sons: New York, 2002; p 2119. ISBN 0-471-31506-0

- ^ a b c d J. A. Keith; P. M. Henry (2009). "The Mechanism of the Wacker Reaction: A Tale of Two Hydroxypalladations". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48 (48): 9038–9049. Bibcode:2009ACIE...48.9038K. doi:10.1002/anie.200902194. PMID 19834921.

- ^ Clement, William H.; Selwitz, Charles M. (January 1964). "Improved Procedures for Converting Higher α-Olefins to Methyl Ketones with Palladium Chloride". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 29 (1): 241–243. doi:10.1021/jo01024a517. ISSN 0022-3263.

- ^ Fahey, Darryl R.; Zeuch, Ernest A. (November 1974). "Aqueous sulfolane as solvent for rapid oxidation of higher .alpha.-olefins to ketones using palladium chloride". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 39 (22): 3276–3277. doi:10.1021/jo00936a023. ISSN 0022-3263.

- ^ Tsuji, Jiro; Shimizu, Isao; Yamamoto, Keiji (August 1976). "Convenient general synthetic method for 1,4- and 1,5-diketones by palladium catalyzed oxidation of α-allyl and α-3-butenyl ketones". Tetrahedron Letters. 17 (34): 2975–2976. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)85504-0. ISSN 0040-4039.

- ^ Tsuji, Jiro (1984). "Synthetic Applications of the Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidation of Olefins to Ketones". Synthesis. 1984 (5): 369–384. doi:10.1055/s-1984-30848. ISSN 0039-7881. S2CID 95604861.

- ^ Kurti, Laszlo; Czako, Barbara (2005). Strategic Applications of named Reactions in Organic Synthesis. 525 B Street, Suite 1900, San Diego, California 92101-4495, USA: Elsevier Academic Press. p. 474. ISBN 978-0-12-429785-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ H. Stangl and R. Jira, Tetrahedron Lett., 1970, 11, 3589–3592

- ^ T. Hosokawa, T. Nomura, S.-I. Murahashi, J. Organomet. Chem., 1998, 551, 387–389

- ^ Zaw, K., Lautens, M. and Henry P.M. Organometallics, 1985, 4, 1286–1296

- ^ Wan W.K., Zaw K., and Henry P.M. Organometallics, 1988, 7, 1677–1683

- ^ P. M. Henry, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1964, 86, 3246–3250.

- ^ James, D.E., Hines, L.F., Stille, J.K. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1976, 98, 1806 doi:10.1021/ja00423a027

- ^ James, D.E., Stille, J.K. J. Organomet. Chem., 1976, 108, 401. doi:10.1021/ja00423a028

- ^ Bäckvall, J.E., Akermark, B., Ljunggren, S.O., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1979, 101, 2411. doi:10.1021/ja00503a029

- ^ Stille, J.K., Divakarumi, R.J., J. Organomet. Chem., 1979, 169, 239;

- ^ Francis, J.W., Henry, P.M. Organometallics, 1991, 10, 3498. doi:10.1021/om00056a019

- ^ Francis, J.W., Henry, P.M. Organometallics, 1992, 11, 2832.doi:10.1021/om00044a024

- ^ Comas-Vives, A., Stirling, A., Ujaque, G., Lledós, A., Chem. Eur. J., 2010, 16, 8738–8747.doi:10.1002/chem.200903522

- ^ Anderson, B.J., Keith, J.A., and Sigman, M.S., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2010, 132, 11872-11874

- ^ J. A. Keith, J. Oxgaard, and W. A. Goddard, III J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 3132 – 3133; doi:10.1021/ja0533139

- ^ H. E. Hosseini, S. A. Beyramabadi, A. Morsali, and M. R. Housaindokht, J. Mol. Struct. (THEOCHEM), 2010, 941, 138–143

- ^ P. L. Theofanis, and W. A. Goddard, III Organometallics, 2011, 30, 4941 – 4948; doi:10.1021/om200542w

- ^ a b c d e f Marc Eckert; Gerald Fleischmann; Reinhard Jira; Hermann M. Bolt; Klaus Golka. "Acetaldehyde". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_031.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Balija, Amy M.; Stowers, Kara J.; Schultz, Mitchell J.; Sigman, Matthew S. (March 2006). "Pd(II)-Catalyzed Conversion of Styrene Derivatives to Acetals: Impact of (−)-Sparteine on Regioselectivity". Organic Letters. 8 (6): 1121–1124. doi:10.1021/ol053110p. ISSN 1523-7060. PMID 16524283.

- ^ Michel, Brian W.; Camelio, Andrew M.; Cornell, Candace N.; Sigman, Matthew S. (2009-05-06). "A General and Efficient Catalyst System for a Wacker-Type Oxidation Using TBHP as the Terminal Oxidant: Application to Classically Challenging Substrates". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 131 (17): 6076–6077. Bibcode:2009JAChS.131.6076M. doi:10.1021/ja901212h. ISSN 0002-7863. PMC 2763354. PMID 19364100.

- ^ Michel, Brian W.; Steffens, Laura D.; Sigman, Matthew S. (June 2011). "On the Mechanism of the Palladium-Catalyzed tert -Butylhydroperoxide-Mediated Wacker-Type Oxidation of Alkenes Using Quinoline-2-Oxazoline Ligands". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 133 (21): 8317–8325. Bibcode:2011JAChS.133.8317M. doi:10.1021/ja2017043. ISSN 0002-7863. PMC 3113657. PMID 21553838.

- ^ a b Dong, Jia Jia; Browne, Wesley R.; Feringa, Ben L. (2014-11-03). "Palladium-Catalyzed anti-Markovnikov Oxidation of Terminal Alkenes" (PDF). Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 54 (3): 734–744. doi:10.1002/anie.201404856. ISSN 1433-7851. PMID 25367376.

- ^ Miller, D. G.; Wayner, Danial D. M. (April 1990). "Improved method for the Wacker oxidation of cyclic and internal olefins". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 55 (9): 2924–2927. doi:10.1021/jo00296a067. ISSN 0022-3263.

- ^ Stragies, Roland; Blechert, Siegfried (October 2000). "Enantioselective Synthesis of Tetraponerines by Pd- and Ru-Catalyzed Domino Reactions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 122 (40): 9584–9591. Bibcode:2000JAChS.122.9584S. doi:10.1021/ja001688i. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ^ Wright, Joseph A.; Gaunt, Matthew J.; Spencer, Jonathan B. (2006-01-11). "Novel Anti-Markovnikov Regioselectivity in the Wacker Reaction of Styrenes". Chemistry - A European Journal. 12 (3): 949–955. Bibcode:2006ChEuJ..12..949W. doi:10.1002/chem.200400644. ISSN 0947-6539. PMID 16144020.

- ^ a b Baiju, Thekke Veettil; Gravel, Edmond; Doris, Eric; Namboothiri, Irishi N.N. (September 2016). "Recent developments in Tsuji-Wacker oxidation". Tetrahedron Letters. 57 (36): 3993–4000. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.07.081. ISSN 0040-4039.

- ^ Muzart, Jacques (August 2007). "Aldehydes from Pd-catalysed oxidation of terminal olefins". Tetrahedron. 63 (32): 7505–7521. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2007.04.001. ISSN 0040-4020.

- ^ Wickens, Zachary K.; Morandi, Bill; Grubbs, Robert H. (2013-09-13). "Aldehyde-Selective Wacker-Type Oxidation of Unbiased Alkenes Enabled by a Nitrite Co-Catalyst" (PDF). Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 52 (43): 11257–11260. doi:10.1002/anie.201306756. ISSN 1433-7851. PMID 24039135.

- ^ Wickens, Zachary K.; Skakuj, Kacper; Morandi, Bill; Grubbs, Robert H. (2014-01-13). "Catalyst-Controlled Wacker-Type Oxidation: Facile Access to Functionalized Aldehydes" (PDF). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 136 (3): 890–893. Bibcode:2014JAChS.136..890W. doi:10.1021/ja411749k. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 24410719.

- ^ Kim, Kelly E.; Li, Jiaming; Grubbs, Robert H.; Stoltz, Brian M. (2016-09-30). "Catalytic Anti-Markovnikov Transformations of Hindered Terminal Alkenes Enabled by Aldehyde-Selective Wacker-Type Oxidation" (PDF). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 138 (40): 13179–13182. Bibcode:2016JAChS.13813179K. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b08788. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 27670712.

- ^ a b Hartwig, John F. (2010). Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis. USA: University Science Books. pp. 717–734. ISBN 978-1-891389-53-5.

- ^ Baeckvall, Jan E.; Bystroem, Styrbjoern E.; Nordberg, Ruth E. (November 1984). "Stereo- and regioselective palladium-catalyzed 1,4-diacetoxylation of 1,3-dienes". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 49 (24): 4619–4631. doi:10.1021/jo00198a010. ISSN 0022-3263.

- ^ Hosokawa, Takahiro; Miyagi, Shyogo; Murahashi, Shunichi; Sonoda, Akio (July 1978). "Oxidative cyclization of 2-allylphenols by palladium(II) acetate. Changes in product distribution". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 43 (14): 2752–2757. doi:10.1021/jo00408a004. ISSN 0022-3263.

- ^ Baeckvall, Jan E.; Granberg, Kenneth L.; Andersson, Pher G.; Gatti, Roberto; Gogoll, Adolf (September 1993). "Stereocontrolled lactonization reactions via palladium-catalyzed 1,4-addition to conjugated dienes". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 58 (20): 5445–5451. doi:10.1021/jo00072a029. ISSN 0022-3263.

- ^ Timokhin, Vitaliy I.; Stahl, Shannon S. (December 2005). "Brønsted Base-Modulated Regioselectivity in the Aerobic Oxidative Amination of Styrene Catalyzed by Palladium". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (50): 17888–17893. Bibcode:2005JAChS.12717888T. doi:10.1021/ja0562806. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 16351120.

- ^ Larock, Richard C.; Hightower, Timothy R.; Hasvold, Lisa A.; Peterson, Karl P. (January 1996). "Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Cyclization of Olefinic Tosylamides". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 61 (11): 3584–3585. doi:10.1021/jo952088i. ISSN 0022-3263. PMID 11667199.